Abstract

Loss-of-function mutations in DJ – 1 are associated with early-onset of Parkinson’s disease. Although DJ – 1 is ubiquitously expressed, the functional pathways affected by it remain unresolved. Here we demonstrate an involvement of DJ – 1 in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in mouse skeletal muscle. Using enzymatically dissociated flexor digitorum brevis muscle fibers from wild-type (wt) and DJ – 1 null mice, we examined the effects of DJ – 1 protein on resting, cytoplasmic [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) and depolarization-evoked Ca2+ release in the mouse skeletal muscle. The loss of DJ – 1 resulted in a more than two-fold increase in resting [Ca2+]i. While there was no alteration in the resting membrane potential, there was a significant decrease in depolarization-evoked Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in the DJ – 1 null muscle cells. Consistent with the role of DJ – 1 in oxidative stress regulation and mitochondrial functional maintenance, treatments of DJ – 1 null muscle cells with resveratrol, a mitochondrial activator, or glutathione, a potent antioxidant, reversed the effects of the loss of DJ – 1 on Ca2+ homeostasis. These results provide evidence of DJ – 1’s association with Ca2+ regulatory pathways in mouse skeletal muscle, and suggest the potential benefit of resveratrol to functionally compensate for the loss of DJ – 1.

Keywords: DJ – 1, DJ – 1 null mice, Ca2+, Resveratrol, Excitation-contraction coupling, Ca2+ release

1. Introduction

DJ – 1 is a ubiquitously expressed protein, which has been linked to the early-onset autosomal-recessive Parkinsonism (Bonifati et al., 2003; Bandopadhyay et al., 2004). DJ – 1 is present in the cytoplasm as well as intracellular organelles, such as the nucleus and mitochondria (Canet-Aviles et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2005). Although the precise function of this protein remains to be determined, mounting evidence indicates that DJ – 1 is a regulator of cellular response to oxidative stress and can directly protect cells from oxidative damage by serving as an antioxidant protein (Kinumi et al., 2004; Taira et al., 2004; Andres-Mateos et al., 2007; Dodson and Guo, 2007). Additionally, DJ – 1 is a transcriptional co-activator that promotes the activities of transcriptional factors including androgen receptor and PPARγ co-activator-1α (PGC-1α) (Takahashi et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2005; Zhong & Xu, 2008). It also promotes the expression of a number of mitochondrial enzymes involved in ROS removal and stabilizes a potent transcriptional regulator of mitochondrial antioxidative proteins, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) (Clements et al., 2006).

Consistent with DJ – 1’s ability to regulate oxidative stress response, DJ – 1 null mice are more susceptible to mitochondrial toxin MPTP-induced neuronal cell loss (Kim et al., 2005). While the loss of DJ – 1 does not replicate the symptoms and neuropathology associated with Parkinson disease (PD), it leads to severe locomotor irregularities and a substantial decrease in grip strength (Chandran et al., 2008), suggesting that loss of DJ – 1 may directly affect muscle function. In support of the role of DJ – 1 in muscle function, a recent study reported that oxidation-mediated inactivation of DJ – 1 is associated with a muscle disorder, Inclusion Body Myositis (Terracciano et al., 2008).

A precise role of DJ – 1 in the muscle function and other tissues remain to be investigated. Since locomotor properties appear to be affected in the DJ – 1 null animals, it is feasible that cellular processes governing muscle contraction could be significantly altered by the loss of DJ – 1. Skeletal muscle contraction is regulated by the excitation–contraction (EC) coupling process. EC coupling is initiated by an action potential that activates the voltage sensors of plasmalemmal ion channels, the dihydropyridine receptors (DHPRs). Activation of DHPRs leads to an initiation of rapid Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) through the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels (RyRs), which subsequently activate the muscle contractile apparatus (Melzer et al., 1995). Conversely, muscle relaxation is achieved by sequestration of Ca2+ by the SR via the SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA). Because EC coupling can be affected by the oxidative state of the cell (Anzai et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2001), a reduced ability to regulate oxidative stress due to loss of DJ – 1 could potentially affect force generation as well as locomotor properties. To assess the role of DJ – 1 in muscle function we evaluated the effects of the loss of DJ – 1 on Ca2+ homeostasis and depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in isolated muscle cells from the DJ – 1 null mice. Using Ca2+ selective microelectrodes to monitor the resting intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) and fluorescent Ca2+ indicator magFluo-4 AM to monitor whole-cell Ca2+ fluxes, we demonstrate that the loss of DJ – 1 leads to substantial elevation of resting [Ca2+]i and decreased Ca2+ release in response to electrical stimulation. Both of these characteristics can be partially reversed by the administration of a mitochondrial functional activator, resveratrol or a potent antioxidant, glutathione. These findings advance our understanding of the role DJ – 1 plays in cellular function.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Muscle fiber preparation

DJ – 1 null and wild-type (wt) mice (Goldberg et al., 2005) were used in this study following a protocol approved by the Caritas St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Homozygous DJ – 1 null and wt mice were generated by breeding of heterozygous DJ – 1 null animals. Age-matched mice (8–12 months old) were euthanized by pentobarbital overdose. Flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles were removed, placed in a Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) solution containing 2 mg/ml collagenase A (Roche, Nutley, NJ) and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C with gentle agitation. Thereafter, muscles were removed from the enzyme-containing media and rinsed twice in DMEM. Muscle bundles were then transferred to DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum, 1% penicillin, 1% streptomycin and 1% glutamine and gently triturated with a polished glass pipette until a significant portion were dissociated to single cells. Myofibers were plated onto ECM-coated (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) glass-bottom 24-well dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) and allowed to settle to the bottom of the dish over night in an incubator at 5% CO2 and 37 °C.

2.2. Fluorescence recording

All reagents, unless otherwise indicated, were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Cells were bathed in a normal Ringer solution containing in [mM]: [125]NaCl, [5]KCl, [1.2]MgSO4, [6]glucose, [25]HEPES, [2]CaCl2, pH 7.4. Myofibers were loaded at room temperature for 30 min in Ringer solution supplemented with Ca2+ indicator dye (magFluo-4AM, 5 μM (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR)). Cells were later washed several times with Ringer solution to terminate further loading and placed in a 37 °C incubator for de-esterification of the dye. To eliminate the motion artifacts due to muscle contraction, N-benzyl-p-toluene sulphonamide (BTS, 50 μM), an inhibitor of the myosin II ATPase, was added to the bathing solution.

Whole-cell fluorescence changes were detected using an IonOptix fluorescence system (IonOptix, Milton, MA) interfaced with an inverted Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope equipped with a Neofluar 40× oil-immersion objective. Changes in fluorescence were detected by a photo multiplier tube.

Ca2+ transients were elicited as described previously (Shtifman et al., 2008). Briefly, supra-threshold rectangular pulses (1 ms duration) were applied through two platinum electrodes placed on opposite sides of the experimental chamber. Changes in intracellular [Ca2+] were characterized as changes in Fluo-4 fluorescence intensity. All experiments were conducted at room temperature (22 °C). Detected changes in fluorescence within each cell were analyzed using IonOptix analysis software (IonOptix, Milton, MA). The resulting fluorescence changes were corrected for the background fluorescence within individual cells by dividing the magnitude of change in fluorescence (ΔF) by the mean baseline fluorescence intensity (F0) to give the ΔF/F values.

2.3. Microelectrode preparation and recording

Microelectrode recordings were performed as described previously (Christensen et al., 2004). Briefly, resting, free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and the plasma membrane potential (Vm) were recorded simultaneously using double-barreled Ca2+-selective microelectrodes that were prepared from thin-walled borosilicate glass capillaries (WPI PB150F-4, Sarasota, FL). Prior to pulling, all capillaries were washed with HCl followed by a rinse with distilled water and then dried at 150 °C for 3 h. Capillaries were pulled to make short-taper microelectrodes with an outside tip diameter of approximately 0.6 μm. The larger barrel (1.5 mm outside diameter) was silanized by exposure to dimethyldichlorosilane vapor. Twenty-four hours later, the tip was backfilled with the neutral carrier, ETH129 (Fluka, Ronkonkoma, NY). The remainder of the barrel was backfilled with pCa7 solution 24 h later. The smaller barrel (0.84 mm outside diameter) was backfilled with 3 M KCl (tip resistance 10–15 M(). All Ca2+-selective microelectrodes were calibrated at 22 °C in solutions of known [Ca2+] before and after the Ca2+ measurements (Alvarez-Leefmans et al., 1981). To better mimic the intracellular ionic conditions all calibration solutions were supplemented with 1 mM Mg2+. Only those Ca2+ microelectrodes that provided a Nernstian response between pCa3 and pCa7 (29.5 mV/pCa unit at 22 °C) were used in this study. The potentials from the 3 M KCl barrel (Vm) and the Ca2+ barrel (VCaE) were recorded via high impedance amplifier (WPI FD-223, Sarasota, FL). The Vm potential was subtracted electronically from VCaE potential, to produce a differential Ca2+-specific potential (VCa) that represents the [Ca2+]i concentration. Vm and VCa were filtered (30–50 KHz) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Recordings were conducted at room temperature (21 °C).

2.4. Western blotting

The hamstring muscles were dissected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The tissues were ground into powder and lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor. Equal amount of proteins were resolved in either 6% for RyR or 4–20% for SERCA1 gels Tris–Glycine gels (Invitrogen. Carlsbad, CA). α-Actin was used as loading control. Antibodies for each protein were from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA).

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test for two independent populations. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at p < 0.05. All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

3. Results

3.1. Elevated resting [Ca2+]i in DJ – 1 null muscle cells

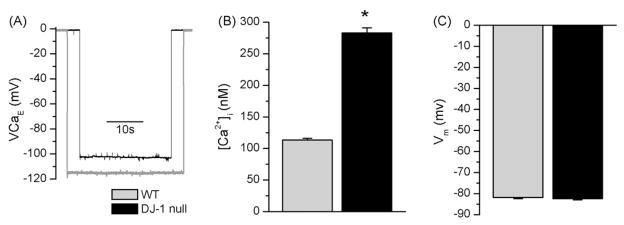

To determine if the loss of DJ – 1 resulted in alteration in resting, myoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), we performed simultaneous microelectrode measurements of [Ca2+]i and membrane potential (Vm) in FDB muscle fibers from wt and DJ – 1 null mice. This method is well suited for accurate and consistent quantitative measurements of sub-sarcolemmal [Ca2+]i in resting cells (Tsien and Rink, 1981) (Alvarez-Leefmans et al., 1981). Representative records of Ca2+ potential obtained from a wt and a DJ – 1 null myofiber are presented in Fig. 1A. As seen from these traces, DJ – 1 null muscle cell exhibited a less negative Ca2+ potential than the wt cells, corresponding to greater [Ca2+]i after electrode calibration. Resting [Ca2+]i in DJ – 1 null muscle fibers was 282.9 ± 8.1 nM (n = 16), which was more than two-fold greater than that observed in wt cells (113.3 ± 2.7 nM, n = 12; p < 0.001, t-test) (Fig. 1B). There was no difference in Vm between wt (81.9 ± 0.6 mV, n = 12) and DJ – 1 null cells (82.4 ± 0.6 mV, n = 16, p > 0.5 t-test) (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Increased [Ca2+]i in DJ – 1 null muscle fibers. Recording of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and resting membrane potential (Vm) with double-barreled microelectrodes in enzymatically dissociated flexor digitorum muscle fibers. A. Representative Ca2+ potential records (VCa) from a wt (gray) and a DJ – 1 null (black) muscle fibers. The initial portion of each trace was obtained prior to impalement of the cells. Penetration and removal of microelectrode was accompanied by immediate downward and upward deflection, respectively. B. Resting [Ca2+]i in wt (n = 12, gray), DJ – 1 null (n = 16, black) muscle cells determined from VCa after calibration of recording microelectrodes. DJ – 1 null cells exhibited a greater then two-fold elevation in [Ca2+]i. C. Resting Vm recorded from the same cells in panel B. Cells from DJ – 1 null animals exhibited Vm similar to those form the wt animals (p > 0.5, t-test). Muscle fibers were prepared from 8 to 12 months old mice. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (p < 0.001, t-test).

3.2. Effects of the loss of DJ – 1 on Ca2+ release

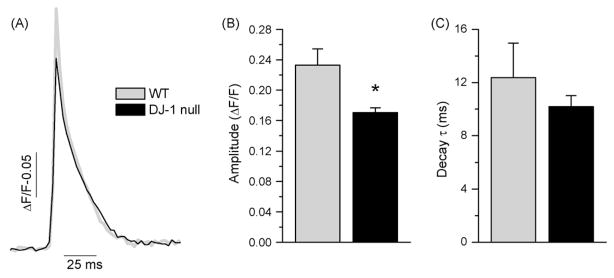

Depolarization-induced Ca2+ fluxes were monitored with a low-affinity Ca2+ indicator, magFluo-4AM, which is an appropriate indicator for examining kinetic parameters of rapid changes in [Ca2+]i. To assess the effect of DJ – 1 loss on SR Ca2+ release, individual, enzymatically dissociated FDB muscle fibers prepared from the wt and DJ – 1 null animals were field stimulated with single pulses (1 ms duration). Muscle fibers readily exhibited Ca2+ release activity in response to each stimulus. Fig. 2A presents the averaged Ca2+ transients from wt (gray) and DJ – 1 null muscle fibers (black). As demonstrated in Fig. 2B Ca2+ transients from the DJ – 1 null muscle fibers exhibited smaller peak amplitudes (0.17 ± 0.006 ΔF/F, n = 22) than those from the wt fibers (0.23 ± 0.02 ΔF/F, n = 17, p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Reduced Ca2+ release in DJ – 1 null muscle fibers. A. Mean Ca2+ transient from wt (gray) (n = 17) and DJ – 1 null (black) (n = 22) FDB muscle fibers measured in response to 1 ms action potential stimuli. B–C. Peak amplitude (ΔF/F) and decay time constant (τ, ms) of Ca2+ transients from wt and DJ – 1 null muscle fibers from the same cells presented in panel A, respectively. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

The time course of decay in FDB muscle fibers from both animals could be well described by a single exponential function. Fig. 2C presents the comparison of decay time constants obtained from DJ – 1 null and wt Ca2+ transients. In wt fibers the decay time constant was 12.37 ± 2.6 ms (n = 22), whereas in DJ – 1 null fibers it was 10.2 ± 0.82 ms (n = 17, p > 0.05). Thus, it appears that Ca2+ clearance mechanisms were not significantly affected by the loss of DJ – 1.

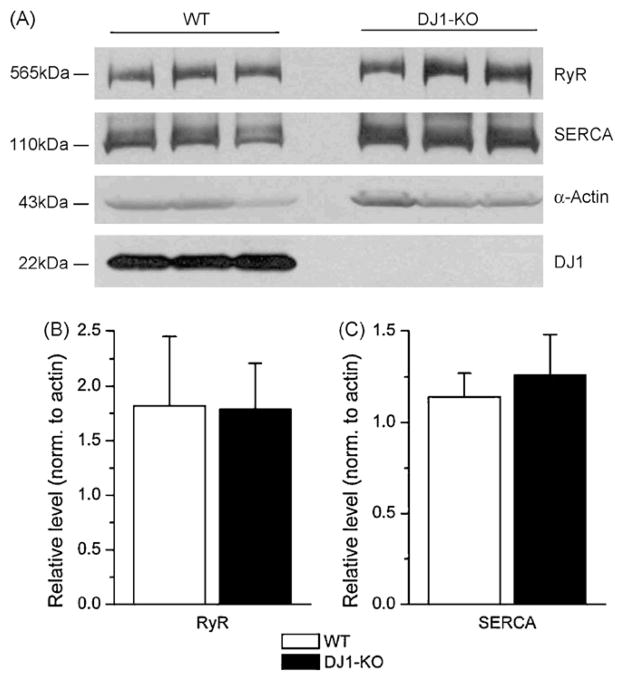

3.3. Expression levels of RyR and SERCA1 in DJ – 1 null muscle

Given that DJ – 1 is a transcriptional regulator, it is feasible that some of the changes in resting [Ca2+]i and Ca2+ release could be due to altered expression levels of key proteins involved in the maintenance of Ca2+ homeostasis. Immunoblots of muscle homogenates from the wt and DJ – 1 null hamstring muscles were used to quantify the expression levels of RyR1, and SERCA1 (Fig. 3A). A quantitative analysis confirmed that there were no significant alterations in the steady-state expression levels of these proteins in the DJ – 1 null muscle (Fig. 3B and C). These results argue against the possibility that altered Ca2+ handling observed in the DJ – 1 null muscle cells was caused by altered expression of the key proteins involved in excitation–contraction coupling.

Fig. 3.

DJ – 1 does not affect the protein expression of RyR1 and SERCA1. A. Immunoblots of RyR1 and SERCA1 protein levels from hamstring muscle of wt and DJ – 1 null mice. The membrane was reprobed for α-actin, which was used as loading control. Bottom panel demonstrates that there was no detectable DJ – 1 protein in the DJ – 1 null muscle. B–C. Quantitative analysis confirmed that there were no significant alterations in the steady-state expression levels of RyR1 (B) and SERCA1 (C) in the DJ – 1 null muscle.

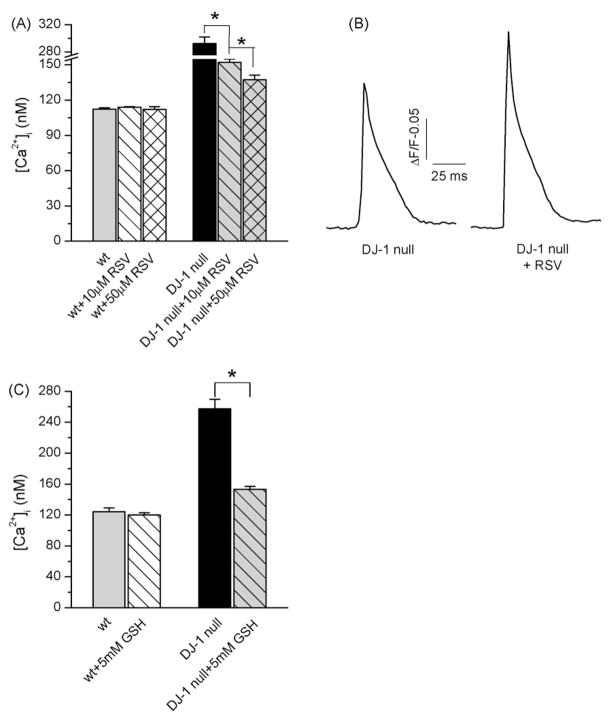

3.4. Reversal of [Ca2+]i and Ca2+ release alterations by resveratrol in DJ – 1 null muscle cells

Resveratrol (trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a phytoalexin produced by plants, and found in the skin of red grapes. It has been demonstrated to exert multifaceted anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in various disease models. Resveratrol treatment mimics the effect of caloric restriction and delay aging by activating sirtuin family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases (Wood et al., 2004; Baur et al., 2006) In addition, resveratrol stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis by activating an energy sensor AMP-activated kinase and increasing the expression of PGC-1α (Baur et al., 2006; Dasgupta and Milbrandt, 2007). Given recent results that show DJ – 1-mediated enhancement of PGC-1α transcriptional activity (Zhong and Xu, 2008) and the role of DJ – 1 in mitochondrial function, we sought to investigate whether treatment of cells with resveratrol could reverse some of the effects caused by loss of DJ – 1. For this purpose, dissociated DJ – 1 null and wt muscle fibers were treated for 18 h with resveratrol (10 μM or 50 μM). Microelectrode recording of resting [Ca2+]i revealed that resveratrol treatment resulted in a dose-dependent reduction of resting [Ca2+]i in DJ – 1 null muscle cells, with no observable effect on resting [Ca2+]i in the wt cells (Fig. 4A). It must be noted that treatment with higher dosage of resveratrol (50 μM) reversed [Ca2+]i in DJ – 1 null cells to a near normal, physiological level (137.4 ± 3.8 nM). In addition to reversal of [Ca2+]i, resveratrol treatment also resulted in an increase in the peak amplitude of action potential-elicited Ca2+ release in the DJ – 1 null muscle fibers (Fig. 4B), without affecting peak amplitudes of Ca2+ transients in the wt cells (not shown).

Fig. 4.

Resveratrol treatment reverses [Ca2+]i changes and improves Ca2+ release in DJ – 1 null muscle cells A. Resting [Ca2+]i measurements performed with Ca2+ selective microelectrodes in wt and DJ – 1 null muscle cells treated for 18 h with 10 μM (nwt = 5, nDJ–1 null = 17) or 50 μM (nwt = 5, nDJ–1 null = 8) resveratrol (RSV). Resveratrol treatment did not have an effect on [Ca2+]i in wt cells, but lowered [Ca2+]i in DJ – 1 null cells in dose-dependent manner. B. Mean Fluo-4 fluorescence transient from untreated DJ – 1 null muscle fibers (left) (n = 15) and DJ – 1 null muscle cells treated for 12 h with 50 μM resveratrol (right) (n = 16). Ca2+ transients were elicited by 1 ms action potential stimuli. Resveratrol treatment increased peak amplitudes of Ca2+ transients in DJ – 1 null cells. C. Resting [Ca2+]i measurements performed with Ca2+ selective microelectrodes in wt and DJ – 1 null muscle cells treated for 18 h with 5 mM glutathione (GSH). GSH treatment did not have an effect on [Ca2+]i in wt cells (n = 4), but lowered [Ca2+]i in DJ – 1 null cells (nDJ–1 null = 6, nDJ–1 null+GSH = 10). Asterisk indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

To determine whether alterations in Ca2+ handling could be reversed by treatments with other antioxidants, experiments were conducted where cells were treated with glutathione (GSH), a potent antioxidant, prior to measuring resting [Ca2+]i. An overnight treatment with GSH (1 mM) did not have an effect on resting [Ca2+]i in either wt or DJ – 1 null muscle fibers (not shown). However, increasing of GSH concentration to 5 mM lead to a substantial decrease in [Ca2+]i in the DJ – 1 deficient cells (153.3 ± 3.7 nM) without affecting [Ca2+]i in wt cells (Fig. 4C). Together, these results demonstrate that antioxidant treatments can reverse changes in Ca2+ handling in DJ – 1 deficient muscle cells.

4. Discussion

This study is the first report that describes a functional link between DJ – 1 and maintenance of Ca2+ homeostasis. Using primary skeletal muscle cells from DJ – 1 null mice, we have found that the loss of DJ – 1 leads to a substantial increase in resting cytoplasmic [Ca2+] and that DJ – 1 null cells consistently exhibit reduced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in response to electrical stimulation. The alteration in Ca2+ handling could be reversed by resveratrol or GSH treatments. These results show an important role for DJ – 1 in muscle function and suggest that dysregulation of Ca2+ homeostasis could be a seminal event in the pathogenic mechanism linked to a loss of DJ – 1.

DJ – 1 is recognized as a protein linked to selected cases of early-onset Parkinson disease (Bonifati et al., 2003). Given its ubiquitous expression, it is important to characterize the physiologic function of DJ – 1, and the consequences of its loss or inactivation. Our current study provides evidence that loss of DJ – 1 leads to the impairment of at least two physiologic processes in skeletal muscle cells, the maintenance of myoplasmic [Ca2+] and stimulated Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. These results are consistent with motor deficits reported in another strain of DJ – 1-null mice (Chandran et al., 2008), and the possible involvement of DJ – 1 inactivation in a skeletal muscle disorder, Inclusion Body Myositis (Terracciano et al., 2008), where similar alterations in Ca2+ handling have been reported (Moussa et al., 2006; Shtifman et al., 2008).

One of the main findings of this study is that a loss of DJ – 1 leads to a substantial elevation of [Ca2+]i in muscle cells. Although caused by different factors, similar alterations in Ca2+ handling were been reported in other skeletal muscle disorders, such as malignant hyperthermia (Lopez et al., 1986, 1992; Yang et al., 2006) and Inclusion Body Myositis (Moussa et al., 2006; Shtifman et al., 2008). Since Ca2+ ions are integral to the proper function of the cells, substantial alterations in basal Ca2+ concentration reported here could either trigger or exacerbate deleterious effects in a myriad of cellular processes. Another aspect of Ca2+ handling that was altered in the DJ – 1 deficient cells is depolarization-induced Ca2+ release. It will be of interest to determine whether an analogous disruption in Ca2+ homeostasis by a loss or inactivation DJ – 1 also occurs in the nervous system. Interestingly, a recent study linked a deficiency in another protein genetically associated with autosomal-recessive PD, PINK1, to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload in neural cells (Gandhi et al., 2009). Another study reported that interplay between α-synuclein, cytosolic dopamine metabolite and intracellular Ca2+ contributes to the selective neurotoxicity in dopaminergic neurons (Mosharov et al., 2009). Reduction of intracellular Ca2+ by channel blocking or buffering significantly reduced the levels of cytosolic dopamine, a key factor in the toxic mix. Based on our current finding and those by others, it is evident that a better understanding of the interplay between the loss of DJ – 1 and altered Ca2+ handling in dopaminergic neuron could lead to a better understanding of PD pathogenesis.

There is considerable evidence that DJ – 1 is involved in the oxidative stress response and in maintenance of mitochondrial function (Dodson and Guo, 2007). Thus, a decrease in functional DJ – 1 or its elimination could lead to an enhanced generation of ROS by the mitochondria. It remains to be determined whether changes in [Ca2+]i and Ca2+ release in the DJ – 1 null cells could have been mediated by oxidative stress. All isoforms of RyRs contain regulatory thiols that are sensitive to RedOx modifications. Once these channels are oxidized, their responsiveness to modulators is altered and they become hyperactive. Hyperactivity of RyR under resting conditions (“Ca2+ leak”) can account for the observed changes in cytoplasmic [Ca2+] in the DJ – 1 null cells. In addition, chronic oxidation of RyRs can also alter Ca2+ release parameters during EC coupling. The possibility that altered Ca2+ handling in the DJ – 1 null cells was potentially mediated by ROS is further supported by the rescue effect of resveratrol and glutathione. While tripeptide glutathione acts as a strong reducing agent to antagonize ROS directly, resveratrol stimulates the activity and expression of PGC-1α, a key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and ROS removal (Wu et al., 1999; Baur et al., 2006; St-Pierre et al., 2006; Dasgupta and Milbrandt, 2007). Interestingly, DJ – 1 may prevent the ROS accumulation by resembling the effects of both glutathione and resveratrol. The DJ – 1 protein, abundant in cysteine and methionine, has been shown to act as antioxidant molecule to directly remove H2O2 (Kinumi et al., 2004; Taira et al., 2004; Andres-Mateos et al., 2007). Furthermore, oxidized DJ – 1 accumulates in the Alzheimer’s disease and PD brains (Choi et al., 2006). In addition to removing free radical directly, DJ – 1 is also a transcriptional regulator (Takahashi et al., 2001; Niki et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2005). We have recently reported a synergy between DJ – 1 and PGC-1α in the transcriptional regulation of the human MnSOD (Zhong and Xu, 2008). Thus, similar to resveratrol, DJ – 1 may enhance PGC-1α activity and lead to the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and ROS removal. It is notable that resveratrol reversed the aberrant Ca2+ handling in DJ – 1 null cells without affecting the Ca2+ homeostasis in muscle cells from the wild-type mice. Given the potent anti-oxidative stress effect of DJ – 1, the resveratrol treatment, especially at the doses used in this study (10 and 50 μM), may not generate additional benefit in the wild-type cells. Since increased oxidation of DJ – 1 has been associated with normal aging (Choi et al., 2006; Meulener et al., 2006), and may lead to attenuated DJ – 1 function (Zhong and Xu, 2008), it will be of interest to investigate whether reseveratrol may affect the Ca2+ signaling in cells from wild-type, aged animals.

The aberrant mitochondrial function resulting from the loss of DJ – 1 and presumed subsequent reduction of ATP production could underlie the alterations in depolarization-induced Ca2+ release reported here. It has been well described that function of main components of the depolarization-induced Ca2+ release, the DHPRs and the RyRs, are strongly dependent on cytoplasmic ATP concentration. For instance, RyR1 is strongly stimulated by ATP binding to the cytoplasmic regulatory site and weakly inhibited by ATP hydrolysis products ADP and AMP (Meissner et al., 1986; Laver et al., 2001). Additionally, voltage sensor-dependent Ca2+ release has been shown to decrease by lowering of intracellular ATP concentration (Owen et al., 1996; Blazev and Lamb, 1999a, b; Dutka and Lamb, 2004). However, it must be noted that in addition to ATP, other metabolic and cellular factors may be involved in reducing Ca2+ release in DJ – 1 deficient cells.

Our results indicate that the steady-state expression of RyRs and SERCA, which are essential for maintenance of myoplasmic [Ca2+] and regulation of Ca2+ release, are not directly affected by the loss of DJ – 1. Nevertheless, abnormal transcriptional regulation due to the loss of DJ – 1 may still be indirectly involved in the Ca2+ dysregulation, given that DJ – 1 is involved in the expression or activity of a number of key proteins essential to mitochondrial function and oxidative stress response. And it is possible that these gene products could modulate the function of either RyRs or SERCA.

In summary, the present data demonstrate considerable alterations in SR Ca2+ release and resting [Ca2+]i arising from the loss of DJ – 1. These results contribute to our understanding of the physiological role of DJ – 1 and provide new insights into molecular mechanisms underlying DJ – 1-associated pathology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by institutional funding from St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center to A.S. and J.X.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

There are no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Alvarez-Leefmans FJ, Rink TJ, Tsien RY. Free calcium ions in neurones of Helix aspersa measured with ion-selective micro-electrodes. J Physiol. 1981;315:531–548. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres-Mateos E, Perier C, Zhang L, Blanchard-Fillion B, Greco TM, Thomas B, Ko HS, Sasaki M, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. DJ – 1 gene deletion reveals that DJ – 1 is an atypical peroxiredoxin-like peroxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14807–14812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703219104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzai K, Ogawa K, Ozawa T, Yamamoto H. Oxidative modification of ion channel activity of ryanodine receptor. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:35–40. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandopadhyay R, Kingsbury AE, Cookson MR, Reid AR, Evans IM, Hope AD, Pittman AM, Lashley T, Canet-Aviles R, Miller DW, McLendon C, Strand C, Leonard AJ, Abou-Sleiman PM, Healy DG, Ariga H, Wood NW, de Silva R, Revesz T, Hardy JA, Lees AJ. The expression of DJ – 1 (PARK7) in normal human CNS and idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2004;127:420–430. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, Prabhu VV, Allard JS, Lopez-Lluch G, Lewis K, Pistell PJ, Poosala S, Becker KG, Boss O, Gwinn D, Wang M, Ramaswamy S, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG, Lakatta EG, Le Couteur D, Shaw RJ, Navas P, Puigserver P, Ingram DK, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazev R, Lamb GD. Adenosine inhibits depolarization-induced Ca(2+) release in mammalian skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 1999a;22:1674–1683. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199912)22:12<1674::aid-mus9>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazev R, Lamb GD. Low [ATP] and elevated [Mg2+] reduce depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in rat skinned skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1999b;520 (Pt 1):203–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren MJ, Schaap O, Breedveld GJ, Krieger E, Dekker MC, Squitieri F, Ibanez P, Joosse M, van Dongen JW, Vanacore N, van Swieten JC, Brice A, Meco G, van Duijn CM, Oostra BA, Heutink P. Mutations in the DJ – 1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003;299:256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1077209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canet-Aviles RM, Wilson MA, Miller DW, Ahmad R, McLendon C, Bandyopadhyay S, Baptista MJ, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Cookson MR. The Parkinson’s disease protein DJ – 1 is neuroprotective due to cysteine-sulfinic acid-driven mitochondrial localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9103–9108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402959101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran JS, Lin X, Zapata A, Hoke A, Shimoji M, Moore SO, Galloway MP, Laird FM, Wong PC, Price DL, Bailey KR, Crawley JN, Shippenberg T, Cai H. Progressive behavioral deficits in DJ – 1-deficient mice are associated with normal nigrostriatal function. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Sullards MC, Olzmann JA, Rees HD, Weintraub ST, Bostwick DE, Gearing M, Levey AI, Chin LS, Li L. Oxidative damage of DJ – 1 is linked to sporadic Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10816–10824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509079200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen RA, Shtifman A, Allen PD, Lopez JR, Querfurth HW. Calcium dyshomeostasis in beta-amyloid and tau-bearing skeletal myotubes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53524–53532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements CM, McNally RS, Conti BJ, Mak TW, Ting JP. DJ – 1, a cancer- and Parkinson’s disease-associated protein, stabilizes the antioxidant transcriptional master regulator Nrf2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15091–15096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607260103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta B, Milbrandt J. Resveratrol stimulates AMP kinase activity in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7217–7222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610068104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson MW, Guo M. Pink1, Parkin, DJ – 1 and mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutka TL, Lamb GD. Effect of low cytoplasmic [ATP] on excitation–contraction coupling in fast-twitch muscle fibres of the rat. J Physiol. 2004;560:451–468. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S, Wood-Kaczmar A, Yao Z, Plun-Favreau H, Deas E, Klupsch K, Downward J, Latchman DS, Tabrizi SJ, Wood NW, Duchen MR, Abramov AY. PINK1-associated Parkinson’s disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Mol Cell. 2009;33:627–638. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MS, Pisani A, Haburcak M, Vortherms TA, Kitada T, Costa C, Tong Y, Martella G, Tscherter A, Martins A, Bernardi G, Roth BL, Pothos EN, Calabresi P, Shen J. Nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits and hypokinesia caused by inactivation of the familial parkinsonism-linked gene DJ – 1. Neuron. 2005;45:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RH, Smith PD, Aleyasin H, Hayley S, Mount MP, Pownall S, Wakeham A, You-Ten AJ, Kalia SK, Horne P, Westaway D, Lozano AM, Anisman H, Park DS, Mak TW. Hypersensitivity of DJ – 1-deficient mice to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrindine (MPTP) and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5215–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501282102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinumi T, Kimata J, Taira T, Ariga H, Niki E. Cysteine-106 of DJ – 1 is the most sensitive cysteine residue to hydrogen peroxide-mediated oxidation in vivo in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver DR, Lenz GK, Lamb GD. Regulation of the calcium release channel from rabbit skeletal muscle by the nucleotides ATP, AMP, IMP and adenosine. J Physiol. 2001;537:763–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JR, Alamo LA, Jones DE, Papp L, Allen PD, Gergely J, Sreter FA. [Ca2+]i in muscles of malignant hyperthermia susceptible pigs determined in vivo with Ca2+ selective microelectrodes. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:85–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JR, Gerardi A, Lopez MJ, Allen PD. Effects of dantrolene on myoplasmic free [Ca2+] measured in vivo in patients susceptible to malignant hyperthermia. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:711–719. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G, Darling E, Eveleth J. Kinetics of rapid Ca2+ release by sarcoplasmic reticulum. Effects of Ca2+, Mg2+, and adenine nucleotides. Biochemistry. 1986;25:236–244. doi: 10.1021/bi00349a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer W, Herrmann-Frank A, Luttgau HC. The role of Ca2+ ions in excitation–contraction coupling of skeletal muscle fibres. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241:59–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(94)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulener MC, Xu K, Thomson L, Ischiropoulos H, Bonini NM. Mutational analysis of DJ – 1 in Drosophila implicates functional inactivation by oxidative damage and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12517–12522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601891103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosharov EV, Larsen KE, Kanter E, Phillips KA, Wilson K, Schmitz Y, Krantz DE, Kobayashi K, Edwards RH, Sulzer D. Interplay between cytosolic dopamine, calcium, and alpha-synuclein causes selective death of Substantia nigra neurons. Neuron. 2009;62:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa CE, Fu Q, Kumar P, Shtifman A, Lopez JR, Allen PD, LaFerla F, Weinberg D, Magrane J, Aprahamian T, Walsh K, Rosen KM, Querfurth HW. Transgenic expression of beta-APP in fast-twitch skeletal muscle leads to calcium dyshomeostasis and IBM-like pathology. FASEB J. 2006;20:2165–2167. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5763fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niki T, Takahashi-Niki K, Taira T, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H. DJBP: a novel DJ – 1-binding protein, negatively regulates the androgen receptor by recruiting histone deacetylase complex, and DJ – 1 antagonizes this inhibition by abrogation of this complex. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen VJ, Lamb GD, Stephenson DG. Effect of low [ATP] on depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle fibres of the toad. J Physiol. 1996;493 (Pt 2):309–315. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtifman A, Ward CW, Laver DR, Bannister ML, Lopez JR, Kitazawa M, Laferla FM, Ikemoto N, Querfurth HW. Amyloid-beta protein impairs Ca(2+) release and contractility in skeletal muscle. Neurobiol Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Silvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jager S, Handschin C, Zheng K, Lin J, Yang W, Simon DK, Bachoo R, Spiegelman BM. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Xu L, Eu JP, Stamler JS, Meissner G. Classes of thiols that influence the activity of the skeletal muscle calcium release channel. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15625–15630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira T, Saito Y, Niki T, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Takahashi K, Ariga H. DJ – 1 has a role in antioxidative stress to prevent cell death. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:213–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Taira T, Niki T, Seino C, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H. DJ – 1 positively regulates the androgen receptor by impairing the binding of PIASx alpha to the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37556–37563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano C, Nogalska A, Engel WK, Wojcik S, Askanas V. In inclusion-body myositis muscle fibers Parkinson-associated DJ – 1 is increased and oxidized. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:773–779. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY, Rink TJ. Ca2+-selective electrodes: a novel PVC-gelled neutral carrier mixture compared with other currently available sensors. J Neurosci Methods. 1981;4:73–86. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(81)90020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430:686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Zhong N, Wang H, Elias JE, Kim CY, Woldman I, Pifl C, Gygi SP, Geula C, Yankner BA. The Parkinson’s disease-associated DJ – 1 protein is a transcriptional co-activator that protects against neuronal apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1231–1241. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Riehl J, Esteve E, Matthaei KI, Goth S, Allen PD, Pessah IN, Lopez JR. Pharmacologic and functional characterization of malignant hyperthermia in the R163C RyR1 knock-in mouse. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1164–1175. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong N, Xu J. Synergistic activation of the human MnSOD promoter by DJ – 1 and PGC-1alpha: regulation by SUMOylation and oxidation. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3357–3367. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]