Abstract

Although studies have been performed to characterize responses of macrophages from individual anatomical sites (e.g., alveolar macrophages) or of murine-derived macrophage cell lines to microbial ligands, few studies compare these cell types in terms of phenotype and function. We directly compared the expression of cell surface markers and functional responses of primary cultures of three commonly used cells of monocyte-macrophage lineage (splenic macrophages, bone-marrow derived macrophages, and bone-marrow derived dendritic cells) with those of the murine-leukemic monocyte-macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7. We hypothesized that RAW 264.7 cells and primary bone marrow-derived macrophages would be similar in phenotype and would respond similarly to microbial ligands that bind to either Toll-like receptors 2, 3, and 4. Results indicate that RAW 264.7 cells most closely mimic bone marrow-derived macrophages in terms of cell surface receptors and response to microbial ligands that initiate cellular activation via Toll-like receptors 3 and 4. However, caution must be applied when extrapolating findings obtained with RAW 264.7 cells to those of other primary macrophage-lineage cells, primarily because phenotype and function of the former cells may change with continuous culture.

Keywords: macrophages, RAW 264.7, bone marrow, spleen, Toll-like receptors

Introduction

Many studies have been performed to characterize the responses of cells of the monocyte-lineage to microbial ligands, particularly to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of E. coli. However, the vast majority of these studies either have used primary cells collected from a single anatomical site (e.g., alveolar macrophages), or cells that were elicited by the administration of an inflammatory stimulus (e.g., thioglycollate)[1–3]. In addition, several monocyte-lineage cell lines are available, including the murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cell line. These cell lines have fundamental differences from the primary cells in that they grow continuously in culture due to permanent alterations in their genes that may have an affect on the signaling cascades that are activated by microbial ligands[4]. The results of studies utilizing individual populations of primary cells or one of the monocyte-lineage cell lines available have been instrumental in developing our understanding of the mechanisms responsible for activation of monocyte-linage cells by microbial ligands. However, it is difficult, to make confident comparisons among studies using cells from different sources without knowing the specific phenotype or differentiation state of those cells. To address this problem, the present study compared responses of primary cultures of splenic macrophages, (SP-Mφ), bone marrow macrophages (BM-Mφ) derived by treatment with macrophage–colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), and bone marrow dendritic cells (BM-DC) derived with a combination of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) to those of the RAW 264.7 cell line (RAW cells). Each cell type was incubated with ligands for Toll-like receptor 2 (synthetic lipopeptide Pam3CSK4), Toll-like receptor 3 (synthetic double-stranded RNA Poly I:C), and Toll-like receptor 4 (lipopolysaccharide, LPS).

Activation of monocyte-linage cells via different Toll-like receptors results in recruitment of specific adaptor proteins (e.g., MyD88 and TRIF) to initiate cell-signaling and synthesis of several down-stream products, including cytokines and chemokines [3, 5, 6]. Production of one down-stream product from each of the cell-signaling pathways, was chosen as a tool to characterize activation by the microbial ligands[7–9]. In this study, we monitored changes in cell supernatant concentrations of TNFα, a key inflammatory cytokine produced primarily after activation of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 [10, 11] by cell wall components of gram positive and gram negative bacteria, respectively, and RANTES (also known as CCL5), a chemokine produced primarily after activation of Toll-like receptor 3 by viral proteins[12]. Although RANTES is produced primarily by T-cells, previous reports have shown production of RANTES by monocyte-lineage cells. [7, 8] Because phenotypic and functional differences exist between monocyte-lineage populations in different tissue locations [13], we also monitored expression of key surface markers for stages of maturation and function for each population.

As RAW cells are often used to study cellular responses to microbes and their products, it is important to know whether they accurately reflect responses of primary cells of monocyte-lineage. In this study, direct comparison of these immortalized cells to three primary cell sources of the monocyte-lineage was conducted. The results of this study provide much needed information as to the functional responses to microbial ligands and phenotype of three commonly used primary monocyte lineage cells from the C57Bl/6 mouse and the widely employed RAW 267.4 cell line. The data reported here provides a basis for comparison of studies conducted using each of these in vitro models.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Nine week old C57Bl/6 mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) were used and housed in a pathogen free environment. All protocols were approved by the University of Georgia Animal Care and Use Committee.

Microbial ligands

Pam3CSK4 and Poly I:C from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA), and E. coli 011:B4 LPS from List Biologicals (Campbell, CA). Stimulants were dissolved in PBS and diluted in complete RPMI medium. Comparisons across cell types were made using a common set of ligand concentrations and cell numbers as described below. Pam3CSK4, Poly I:C, and LPS were used to stimulate cells at final concentrations of 10 µg/ml, 100 µg/ml and 1 µg/ml, respectively. Cells were stimulated with each ligand for 20 hours, the optimal time point for generating measureable amounts of our cytokines of interest, based on previous experiments[14] and preliminary data with cell types used in the current study.

Splenic macrophages

Sp-Mφ were harvested using sterile techniques as described previously [15]. Splenocytes were washed with PBS, after which Sp-Mφ were enriched via negative selection with beads coated with anti-CD45R and anti-CD90 antibodies (Miltinyi Auburn, CA), passed through two MACS magnetic columns, and suspended in complete RPMI medium. (FBS, HyClone ultralow endotoxin, Logan, UT). After enrichment, approximately 40% of the negatively selected SP-Mφ were positive for CD11b, and approximately 15% were CD11c positive; only a small number of cells stained positively for CD14, F4/80, and MHC class II (4%, 11% and 22%, respectively) indicating that this collection of cells consisted of a mixture of “resident macrophage” and antigen-presenting cells that had been differentiated within the SP-Mφ. Clearly, this was not a monomorphic population. Sp-Mφ were suspended at either 5 × 106 cells/ml for phenotyping by flow cytometry or at 5 × 105 cells/ml for experiments in which cellular responses to the microbial ligands were evaluated.

Bone Marrow Cell Isolation

Bone marrow cells were harvested using sterile techniques as described previously [16]. Bone marrow cells from groups of mice were pooled, washed with PBS, and suspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in complete RPMI. Three quarters of cells were used to derive BM-Mφ and one quarter to derive BM-DC.

Bone Marrow Derived Macrophages

Bone marrow cells were plated on sterile glass petri dishes. Recombinant murine macrophage-colony stimulating factor (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, Mn) was added to cell cultures (10 ng/ml) incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. BM-Mφ were generated as previously described[17]. After 6 days of incubation, the BM-Mφ were used at 5 × 105 cells/ml in experiments in which responses to the microbial ligands were monitored. After being differentiated in culture, the BM-Mφ population comprised approximately 70% of the total cell population based on expression of both CD11b and F4/80 identified by staining with appropriate monoclonal antibodies. The remaining cells bore markers consistent with cells that were differentiating toward an antigen-presenting cell phenotype, particularly with the higher than expected level of expression of MHC class II.

Bone Marrow Derived Dendritic Cells

Bone marrow cells were plated in six well tissue culture plates, and recombinant granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor and IL-4 (10 ng/ml each) (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were added to cell cultures, to derive BM-DCs as previously described[18]. After 6 days of incubation, the BM-DCs were used at 5 × 105 cells/ml for ELISAs and at 2×106 cells per ml for flow cytometry. Although there is no marker that can be used to determine the heterogeneity of the BM-DC population, almost 80% of these cells were MHC class II positive, at least 24% were CD11c positive, and no more than 20% were F4/80 positive. These findings are consistent with differentiation into cells having immature DC functions. Essentially all of these cells were CD11b positive. Although the level of CD14 expression was not measured, it appears that most of these cells retained some characteristics of monocytes.

RAW 264.7 cells

RAW cells used in this study were obtained from ATCC at an unspecified passage and passed less than 30 times in our laboratory. RAW cells were maintained in complete RPMI. After at least 14 days of incubation, the RAW cells were used at 5 × 105 cells/ml for ELISAs and at 2×106 cells per ml for flow cytometry.

Cell Stimulation

Cells were seeded in 12-well tissue culture plates at the aforementioned concentrations and the microbial ligands (or media alone) were added to duplicate wells at their respective final concentrations. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 hours, after which cell supernatants were collected and stored frozen at −80°C until assayed.

Phenotyping

RAW cells, Sp-Mφ, BM-Mφ, and BM-DCs were stained with fluorescently conjugated anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against the following cell surface proteins: CD11b-FITC, CD11b-Pe-Cy5 (for BM-DC only), CD11c-PE, CD14-PE, CD40-PE-Cy5, F4/80-FITC, MHC class I- FITC, and MHC class II-PE-Cy5 (eBioScience, San Diego, CA) with antibodies at concentrations that were optimized in preliminary studies. Flow analysis was conducted on an Accuri C6 Cytometer (Accuri Cytometers, Ince, Ann Arbor, MI) and assessed for the percent of fluorescent staining and staining brightness using Accuri analysis software.

ELISA

Concentrations of TNF-α and RANTES in cell supernatants were determined using commercially available murine ELISA kits (eBioscience and R & D Systems, respectively). Briefly, 96-well plates were incubated with capture antibodies to coat the wells, washed, and blocked to prepare for the addition of the samples and standards. Samples and standards were added, allowed to incubate, washed, and detection antibodies were added. After incubation and an additional wash step, streptavidin-HRP was added, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The plates were again washed prior to addition of the substrate solution, after which the plates were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was terminated by the addition of stop solution, and the optical density of the wells was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (MXR, Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA). Values for the samples were compared to those for the standard curve.

Data Analysis

Data for both phenotype and response to microbial ligands were analyzed One way ANOVA followed by Tukeys Post hoc test using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Ca). Significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Phenotyping

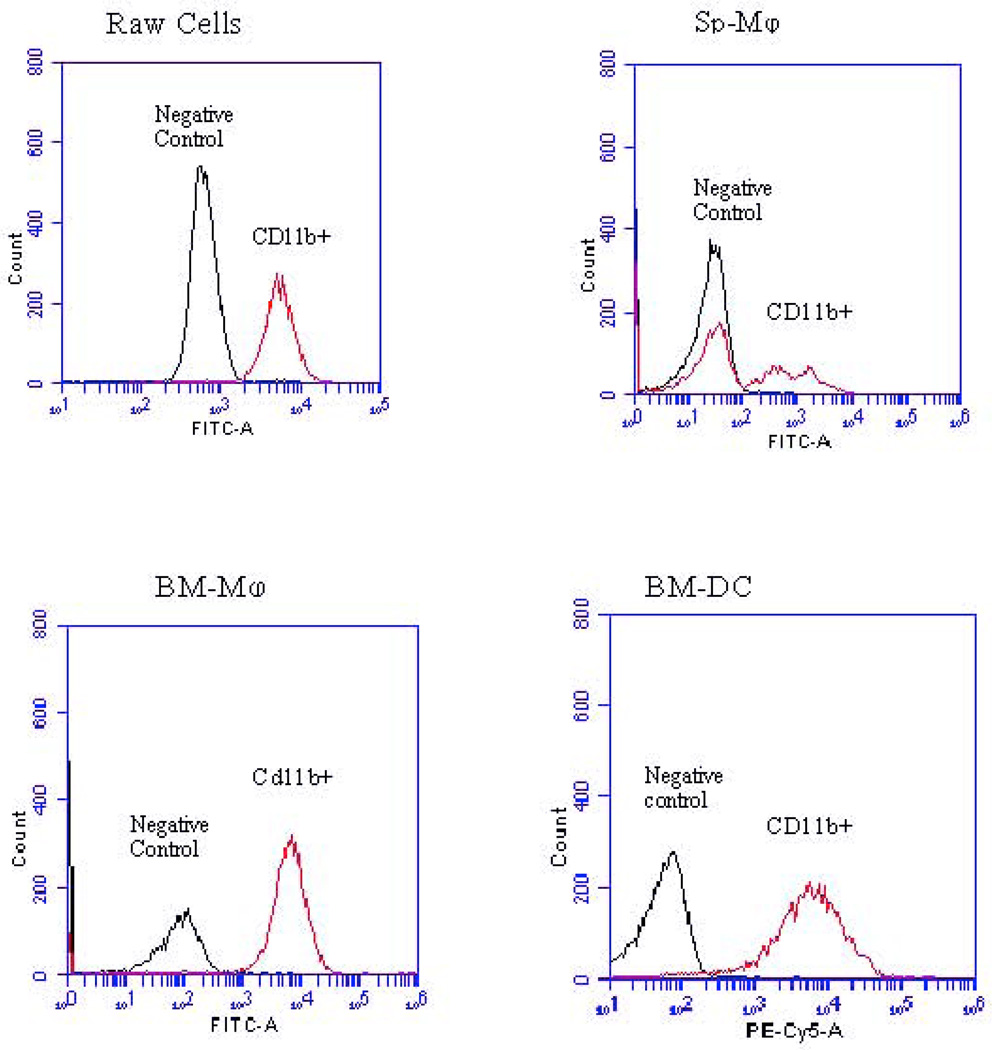

Among the four populations of cells examined, BM-Mφ and RAW cells had the most similar phenotypes, with both populations expressing high levels of CD11b and F4/80 expression relative to the other two cell populations. However, the phenotypes of the BM-Mφ and RAW cells were not identical. RAW cells had a much higher level of expression of CD14 (88.9%) than the other populations tested, including BM-Mφ (53.1%). Sp- Mφ had the lowest level of expression of CD11b, CD14, CD40 and F4/80 of the populations of cells tested, and a typical fraction of cells expressing CD11c relative to the other populations. BM-DC had a very high level of CD11b expression (91.5%), but much lower expression of the other three markers tested (CD11c, CD40, and F4/80). While greater than 70% of RAW cells, Sp-Mφ, and BM-Mφ were positive for MHC I, only BM-DC were strongly positive for MHC II. (Table 1, Figure 1)

Table 1.

Phenotype of primary populations of monocyte derived cells and RAW cells. Mean percent positive cells after staining with monoclonal antibodies recognizing CD11b, CD11c, CD14, CD40, F4/80, MHC I, and MHC II (+/− SEM) are presented in this table.

| Cells | CD11b | CD11c | CD14 | CD40 | F4/80 | MHC I | MHC II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAW |

88.6 +/− 4.7a |

14.4 +/− 2.4 |

88.9 +/− 2.8a,b |

5.4 +/− 2.3b |

79.5 +/− 5.7 a,c |

74.4 +/− 7.2 |

1.2 +/− 0.5a,b,c |

| BM-Mφ |

76.3 +/−16.6 |

26.8 +/−13.3 |

53.1 +/− 2.3a |

27.0 +/− 8.9a |

60.9 +/− 16.9a,c |

76.1 +/− 15.5a,c |

41.6 +/− 14.5 |

| SP-Mφ |

39.6 +/−6.8 |

15.2 +/− 1.3 |

3.9 +/− 0.9 |

0.5 +/− 0.1 |

10.9 +/− 0.4 |

88.9 +/− 8.3c |

22.8 +/− 2.4c |

| BM-DC |

91.5 +/− 0.9a |

24.0 +/− 8.0 |

ND |

13.2 +/− 5.5 |

18.9 +/− 6.8 |

42.7 +/− 18.4 |

78.9 +/− 2.7 |

Superscripts indicate significant differences between cell types, with (a) significantly different from Sp-Mφ, (b) significantly different from BM-Mφ, and (c) significantly different from BM-DC. ND indicates that the marker was not detected.

Figure 1.

Representative results of an experiment is which cells within each population were stained for CD11b. CD11b staining for each cell type is shown relative to its corresponding negative control.

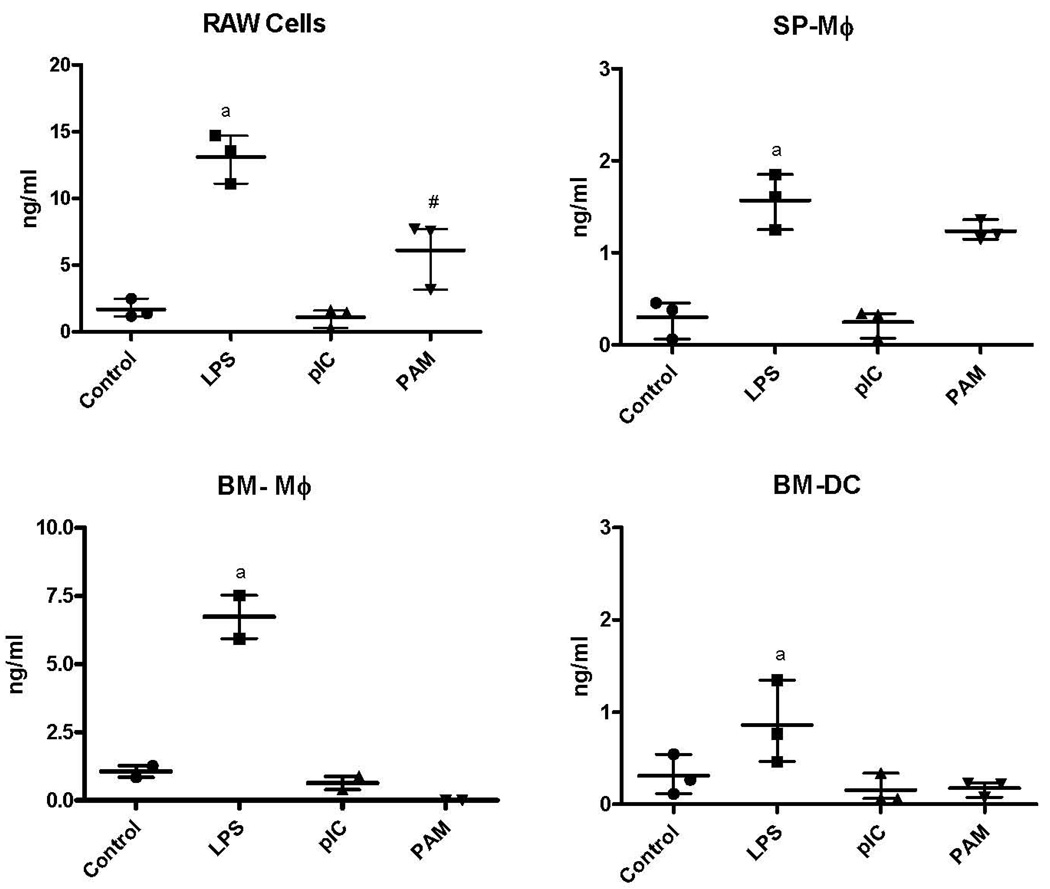

TNF α production

All four of the cell populations produced significantly higher concentrations of TNFα after stimulation with LPS, than when incubated with medium alone. RAW cells and BM-Mφ incubated with LPS produced significantly higher concentrations of TNFα than either the SP-Mφ or BM-DC. RAW cells also produced significantly more TNFα in response to Pam3CSK4 than any of the other cell populations. None of the cell populations produced significant concentrations of TNFα when incubated with pIC. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

TNFα concentrations (mean with range of values of three replicate experiments) in supernatants of RAW cells, Sp-Mφ, BM-Mφ, and BM-DC incubated in media alone (control) or media containing LPS, poly I:C (pIC), or Pam3CSK4 (PAM). All four of the cell populations produced significantly higher concentrations of TNFα after incubation with LPS, than when incubated with medium alone (indicated by “a”). TNFα production by RAW cells when stimulated with PAM was significantly above that produced by other cell types (indicated by #).

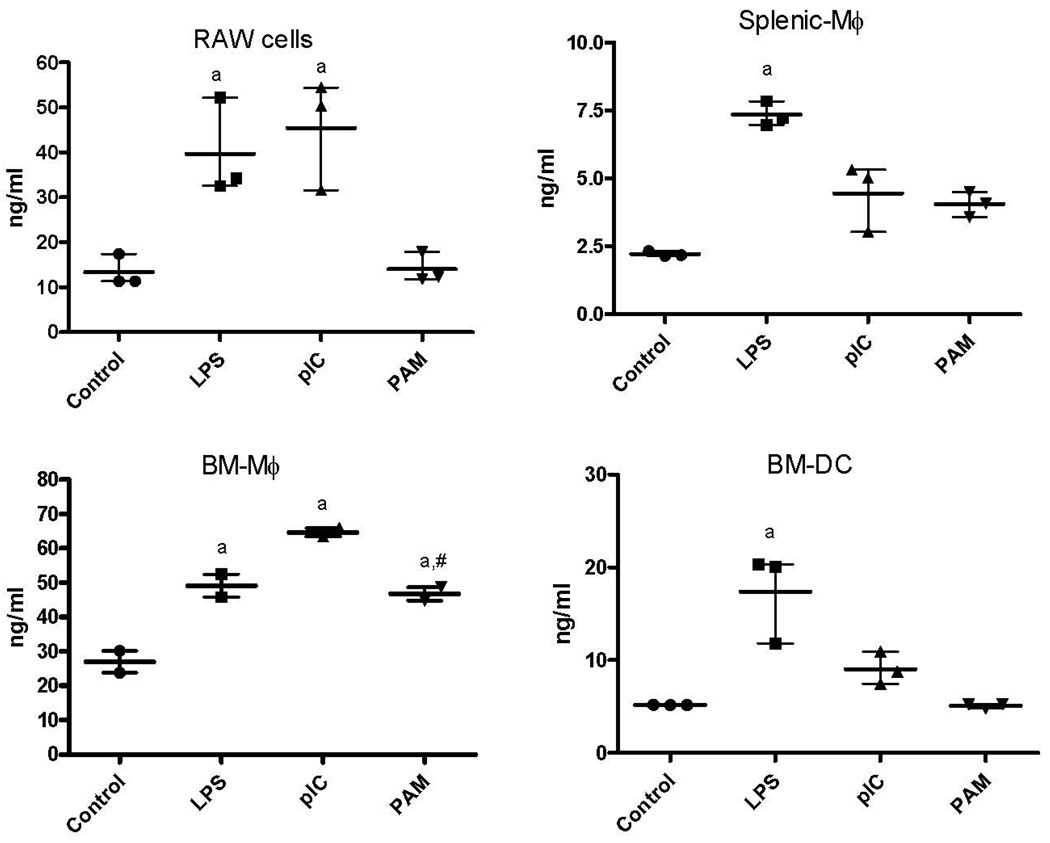

RANTES production

All four of the cell populations produced significantly higher concentrations of RANTES after incubation with LPS, than when incubated with medium alone. RAW cells, SP-Mφ and BM-Mφ incubated with pIC produced significantly higher concentrations of RANTES than when incubated with medium only. BM-Mφ produced significantly more RANTES when incubated with Pam3CSK4 than the same population of cells in medium alone. RAW cells and BM-Mφ produced significantly larger amount of RANTES when incubated with any of the three microbial ligands than did the SP-Mφ and BM-DC. BM-Mφ also produced significantly more RANTES when incubated with Pam3CSK4 than did RAW cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

RANTES concentrations (mean with range of values of three replicate experiments) in supernatants of RAW cells, Sp-Mφ, BM-Mφ, and BM-DC incubated in media alone (control) or media containing LPS, poly I:C (pIC), or Pam3CSK4 (PAM). All four of the cell populations produced significantly higher concentrations of RANTES after incubation with LPS, than when incubated with medium alone (indicated by “a”). RANTES production by BM-Mφ when stimulated with PAM was significantly above that produced by other cell types (indicated by #).

DISCUSSION

To a great extent, our current understanding of macrophage function is based on studies performed with primary cells isolated from individual tissue sources or with cells from immortalized cell lines of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. While the results obtained from such studies often are extrapolated to macrophages from other sources, there have been few direct comparisons made across different primary sources of macrophages, or comparing primary cells to the most commonly used monocyte derived line, RAW 264.7 cells. It is also important to recognize that monocyte-derived cells exist as a highly plastic population of cells with varied functional capabilities [19]. Furthermore, there is no evidence that monocytes are precommitted to a particular functional path, but rather are able to assume the role demanded by the “voice of the tissue”. While it is possible to characterize the specific functional differentiation of these cells by the markers they display in culture, the cells are not immortally relegated to a specific functional role. Because there are no unique sets of markers that define the tissue “management” or antigen-presenting roles of monocyte-derived cells, in this study we compared imperfectly polarized cells collected from the spleen with bone marrow cells that were encouraged towards a functional state based on the cell culture conditions. Consequently, this study provided cells at different functional states against which the RAW 264.7 cells could be compared.

The study reported here sought to determine if responses of RAW cells to microbial ligands directly reflected responses of cells from any or all of the three commonly used sources of primary monocyte-derived cells, namely SP-MΦ, BM-MΦ, and BM-DC. One product each from the TRIF dependent pathway (TNFα) and the MyD88 dependent pathway (RANTES) of signaling by Toll-like receptors was chosen to evaluate cellular responses. To increase the breadth of the comparisons being made, the four cell types were stimulated with LPS, Pam3CSK4 and poly I:C, microbial ligands for Toll-like receptors 2, 3 and 4, respectively, and the phenotype of each was compared using monoclonal antibodies recognizing surface receptors associated with macrophages or dendritic cells.

The results of the current study indicate that strong similarities exist between RAW cells and BM-Mφ, both in expression of key surface molecules and responses to the three microbial ligands. For example, surface expression of CD 14, an important co-receptor with Toll-like receptor 4 for LPS [20], was significantly greater on both RAW cells and BM-Mφ than on SP-Mφ. Furthermore, when stimulated with LPS, the RAW cells and BM-Mφ produced significantly higher concentrations of TNFα and RANTES than did SP-Mφ and BM-DC. These findings are consistent with the fact that the presence of membrane bound CD14 greatly increases the sensitivity of cells to LPS [21].

The results of recent studies indicate that CD14 also enables binding of Pam3CSK4 to Toll-like receptor 2 by facilitating the recognition of the bound lipopeptide by Toll-like receptor 2[22]. In the current study, BM-Mφ and RAW cells produced significantly more TNFα in response to Pam3CSK4 than either the SP-Mφ or BM-DC, a finding that is consistent with the marked differences in expression of CD14.

CD14 is recognized as a macrophage marker, and mature dendritic cells do not express this surface marker[23]. Thus, the low level of production of TNFα after stimulation with either LPS or PAM3CSK4 by BM-DC is consistent with their differential phenotype.

BM-Mφ and RAW cells also responded similarly to stimulation with poly I:C through Toll-like receptor 3. The similarities in their responses to LPS, Pam3CSK4 and poly I:C indicate that both BM-Mφ and RAW cells represent a common point in the monocyte-macrophage differentiation pathway. While there are no similar comparative reports that have been previously published, the striking similarity in the phenotypes, including the concordance in expression of CD14 and F4/80 between BM-Mφ and RAW cells probably represents a differentiation state-related indicator of their functional capacity.

All four types of macrophages produced TNFα and RANTES in response to LPS, albeit with different magnitudes of response. These differences in cytokine production may reflect differences in degrees of maturation relative to fully differentiated macrophages or dendritic cells, and reflect the specialized function of each of the types of cells. Resident macrophages are derived from circulating monocytes and differentiate in their final microenvironments[20]. In particular, the mouse spleen contains a heterogeneous mixture of macrophages, with at least five distinct subpopulations having been identified. Each of these populations is characterized by a specific level of surface receptor expression, functional activity, and location within the spleen [20]. In the current study, the SP-Mφ produced the smallest quantities of TNFα and RANTES in response to all three microbial ligands on an equivalent cell number basis. This may reflect the heterogeneity of the population being studied. No attempt was made in the current study to isolate individual sub-populations of SP-MΦ.

Based on their ubiquitous use to study macrophage function [20], RAW cells have recently been compared with BM-Mφ and three other continuous murine macrophage cell lines, based on their phenotype and function[24]. Because each of the macrophage-like cell types responded differently to LPS, the authors of that study recommended that investigators should be cautious when choosing an immortalized cell line for studies in which generalizations are to be made regarding macrophage function. Furthermore, the authors of an additional recent study expressed concerns about the use of RAW cells, as they were found to induce lymphoma in newborn mice and to contain an endogenous tumor virus [4].

The current study has parallels to the recent report by Chamberlain and co-workers [24] in which bone marrow derived macrophages from C57BL/6 mice were compared against three commonly utilized mouse macrophage-like cell lines, including RAW cells for their capacity to mount inflammatory responses to biomaterials and LPS. For example, the culture conditions for the RAW cells were essentially identical to the conditions used in the present study. In contrast to the present study, however, their bone marrow-derived macrophages were generated using L929 conditioned medium over seven days in culture rather than in response to incubation with recombinant macrophage colony stimulating factor. In both studies, the bone marrow-derived macrophages and RAW cells expressed relatively high levels of F4/80 and CD11b, the RAW cells expressed more CD14 than the bone marrow macrophages, and both cell types expressed a lower level of CD11c than CD11b. There were two significant differences between the results of the two studies in the expression of the cell surface markers. Firstly, F4/80 was expressed at a significantly higher level on the bone marrow macrophages than RAW cells in the study by Chamberlain and co-workers, whereas there was not a significant difference in the levels of expression of F4/80 in the present study. Secondly, they reported that RAW cells strongly express MHC II [24], while we found that expression of MCH II by RAW cells was extremely low.

In both studies, bone marrow macrophages and RAW cells responded to incubation with LPS by producing significantly greater amounts of TNF-α and chemokine than unstimulated control cells. Furthermore, in both studies the RAW cells and bone marrow macrophages produced comparable amounts of these inflammatory mediators.

Based on the results of the present study, it appears that RAW cells most closely resemble BM-Mφ both in phenotype and function, a conclusion that is supported by the results of the study by Chamberlain and co-workers [24]. However, it is important to note that RAW cells are not cloned and their phenotype and function have been recognized to change under conditions of continuous culture. It is also well recognized that cells from primary culture change after multiple passages. As a result, it is advisable that any cell lines carried over a number of passages be monitored on a regular basis for their responses to specific stimuli of interest, and their phenotype be assessed shortly before they are used in an experiment. In this manner, laboratories should be able to maintain a consistent, viable source of immortalized macrophage-like cells for in vitro assays. However, caution must be applied when extrapolating findings obtained with RAW cells to those of primary macrophage-lineage cells. Clearly, side-by-side comparisons should be performed before any generalizations are made.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Institute of General Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (GM061761).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors do not have any conflict of interest that would bias this manuscript.

References

- 1.Corradin SB, Mauel J, Gallay P, Heumann D, Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Enhancement of murine macrophage binding of and response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by LPS-binding protein. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;52:363–368. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suda Y, Kirikae T, Shiyama T, Yasukochi T, Kirikae F, Nakano M, Rietschel ET, Kusumoto S. Macrophage activation in response to S-form lipopolysaccharides (LPS) separated by centrifugal partition chromatography from wild-type LPS: effects of the O-polysaccharide portion of LPS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:678–685. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nozawa RT, Yanaki N, Yokota T. Cell growth and antimicrobial activity of mouse peritoneal macrophages in response to glucocorticoids, choleragen and lipopolysaccharide. Microbiol Immunol. 1980;24:1199–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1980.tb02924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartley JW, Evans LH, Green KY, Naghashfar Z, Macias AR, Zerfas PM, Ward JM. Expression of infectious murine leukemia viruses by RAW264.7 cells, a potential complication for studies with a widely used mouse macrophage cell line. Retrovirology. 2008;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aderem A. Role of Toll-like receptors in inflammatory response in macrophages. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S16–S18. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones BW, Heldwein KA, Means TK, Saukkonen JJ, Fenton MJ. Differential roles of Toll-like receptors in the elicitation of proinflammatory responses by macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60 Suppl 3:iii6–iii12. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.90003.iii6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjorkbacka H, Fitzgerald KA, Huet F, Li X, Gregory JA, Lee MA, Ordija CM, Dowley NE, Golenbock DT, Freeman MW. The induction of macrophage gene expression by LPS predominantly utilizes Myd88-independent signaling cascades. Physiol Genomics. 2004;19:319–330. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00128.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirotani T, Yamamoto M, Kumagai Y, Uematsu S, Kawase I, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Regulation of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes by MyD88 and Toll/IL-1 domain containing adaptor inducing IFN-beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, Akira S. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevenson MM, Huang DY, Podoba JE, Nowotarski ME. Macrophage activation during Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection in resistant C57BL/6 and susceptible A/J mice. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1193–1201. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1193-1201.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy JA. The unexpected pleiotropic activities of RANTES. J Immunol. 2009;182:3945–3946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0990015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Furth R, Diesselhoff-den Dulk MM. Characterization of mononuclear phagocytes from the mouse, guinea pig, rat, and man. Inflammation. 1982;6:39–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00910718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueiredo MD, Vandenplas ML, Hurley DJ, Moore JN. Differential induction of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways in equine monocytes by Toll-like receptor agonists. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;127:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiigi BBMaSM. Selected Methods in Cellular Immunology. W. H. Freeman and Company; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanley ER. Murine bone marrow-derived macrophages. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;75:301–304. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-441-0:301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alatery A, Basta S. An efficient culture method for generating large quantities of mature mouse splenic macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 2008;338:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rossner S, Koch F, Romani N, Schuler G. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hume DA. Macrophages as APC and the dendritic cell myth. J Immunol. 2008;181:5829–5835. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor PR, Martinez-Pomares L, Stacey M, Lin HH, Brown GD, Gordon S. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:901–944. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JD, Kato K, Tobias PS, Kirkland TN, Ulevitch RJ. Transfection of CD14 into 70Z/3 cells dramatically enhances the sensitivity to complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1697–1705. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakata T, Yasuda M, Fujita M, Kataoka H, Kiura K, Sano H, Shibata K. CD14 directly binds to triacylated lipopeptides and facilitates recognition of the lipopeptides by the receptor complex of Toll-like receptors 2 and 1 without binding to the complex. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1899–1909. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chamberlain LM, Godek ML, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Grainger DW. Phenotypic non-equivalence of murine (monocyte-) macrophage cells in biomaterial and inflammatory models. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;88:858–871. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]