Abstract

Taking advantage of a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator selectively targeted to the trans-Golgi lumen, we here demonstrate that its Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms are distinct from those of the other Golgi subcompartments: (i) Ca2+ uptake depends exclusively on the activity of the secretory pathway Ca2+ ATPase1 (SPCA1), whereas the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) is excluded; (ii) IP3 generated by receptor stimulation causes Ca2+ uptake rather than release; (iii) Ca2+ release can be triggered by activation of ryanodine receptors in cells endowed with robust expression of the latter channels (e.g., in neonatal cardiac myocyte). Finally, we show that, knocking down the SPCA1, and thus altering the trans-Golgi Ca2+ content, specific functions associated with this subcompartment, such as sorting of proteins to the plasma membrane through the secretory pathway, and the structure of the entire Golgi apparatus are dramatically altered.

Keywords: GFP, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, secretory pathway Ca2+ ATPase1

In addition to its known functions in processing and sorting of lipids and proteins (1), the Golgi Apparatus (GA) is known to play a key role as intracellular Ca2+ store, in synergy with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (2–4). In particular, using a specifically Golgi-targeted aequorin (Go-Aeq) as Ca2+ sensor, the GA has been demonstrated to release Ca2+ into the cytoplasm in response to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) generation and to take up Ca2+ primarily via the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), but also, in part, via the secretory pathway Ca2+ ATPase1 (SPCA1) (2, 3, 5). On the basis of indirect evidence, it has also been suggested that the Ca2+ content of the organelle (6) is relevant in the control of several intra-GA processes (7–10) and indeed mutations of the GA SPCA1 lead to a dominant form of skin pathology, Hailey–Hailey disease (11–13).

Most of these studies, however, have treated the GA as a homogeneous compartment, although it is well established that the GA is structurally and functionally heterogeneous. In particular, the GA is divided into three main polarized subcompartments, the cis-, medial, and trans-Golgi, with distinctive structural and functional characteristics (14–17). It is unknown whether the functional and structural differences of the GA are paralleled by different mechanisms of Ca2+ handling, given that the available methodologies in living cells allow only a crude, overall Golgi analysis, whereas the electron microscopic techniques (x-ray microanalysis or electron energy loss imaging) not only do not permit a dynamic investigation within specific GA subcompartments, but also can give estimates of only the total Ca2+ concentration.

In this contribution we have addressed the problem of the possible heterogeneity of Ca2+ homeostasis in the GA by developing a genetically encoded fluorescent Ca2+ indicator specifically targeted to the trans-Golgi (TG). We show that the TG takes up Ca2+ almost exclusively via SPCA1 and does not express SERCA and IP3 receptors, but in neonatal cardiac myocytes is endowed with functional ryanodine receptors (RyRs). Last, but not least, we show that a reduction of the Ca2+ content within the TG is associated with a dramatic modification of the cisternae morphology and with an alteration in the trafficking of proteins destined to the plasma membrane.

Results

Subcellular Localization of the Golgi Ca2+ Probe.

D1cpv is a genetically encoded, low affinity, Ca2+ indicator in which GFP variants, here referred as CFP and YFP, are linked by a modified calmodulin and a calmodulin-binding domain, M13 (18), as in the original cameleon probe (19). Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between CFP and YFP is maximal at high [Ca2+] and minimal at low [Ca2+]. Accordingly, the efficiency of FRET, and thus [Ca2+], can be conveniently measured on the basis of the ratio (R) between the intensities of YFP/CFP fluorescence emissions upon selective excitation of CFP (18).

D1cpv was modified by introducing at the N terminus a classical Golgi targeting sequence that corresponds to the first 69 amino acids (containing the membrane-spanning domain) of the GA enzyme sialyl-transferase I (2). Sialyl-transferase is a typical TG (and TG network, TGN) resident protein and accordingly the chimeric protein was expected to localize specifically in this GA subcompartment. Indeed, when HeLa cells expressing the new probe (Go-D1cpv; Fig. 1A) were fixed and immunolabeled with antibodies against a canonical TGN protein, TGN46 (Fig. 1B), the overlap of the two signals in the perinuclear GA region was excellent (Fig. 1C); no Go-D1cpv signal was found at the TGN vesicle level. On the contrary, when transfected cells were immunostained with antibodies against a canonical marker of the cis-Golgi compartment (GM130), a substantial mismatch was observed (Fig. S1), especially evident in some planes. The merg-ing picture and a plot line analysis of signal colocalization report a clear mismatch between the cis-Golgi marker, GM130, and the probe (Fig. S1 C and D); on the other hand, GoD1cpv distribution appears to overlap well with the marker of the TG com-partment, TGN46 (Fig. S1 G and H). A 3D reconstruction image of one cell is presented in Movie S1 and Movie S2, where the merging of these two latter signals appears practically complete, indicating that the probe is localized almost exclusively in the perinuclear trans-most cisternae of the GA.

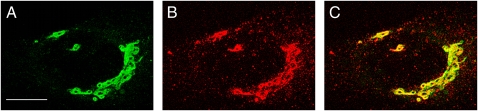

Fig. 1.

Localization of the Go-D1cpv probe in HeLa cells. Fluorescence images correspond to a Z-projection of 10 confocal sections of an HeLa cell expressing the Ca2+ sensor and either (A) excited at 488 nm or (B) decorated with antibody against the trans-Golgi marker TGN46 and excited at 543 nm. (C) Merging of the two previous images; the yellow color indicates overlapping of the green and red signals. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

To quantify the results, a colocalization analysis (Methods) on multiple Z-stacks of these cells was carried out: both the two colocalization indexes obtained (Pearson's, Rr, 0.546 ± 0.052 and 0.077 ± 0.019, and Mander's, R, 0.843 ± 0.020 and 0.650 ± 0.006 for Go-D1cpv/TGN46 and Go-D1cpv/GM130, respectively; mean ± SEM, n ≥ 13) are significantly different for the two markers (P < 0.0001; unpaired Student's t test), indicating a much better colocalization of our probe with the TGN46. Moreover, immunogold EM analysis was performed using anti-GFP, -TGN46, and -GM130 antibodies. A quantitative analysis of the codistribution of the GFP signal with either the cis- or the trans-Golgi marker confirms the better matching of our probe with this latter one, with a colocalization of the two gold particles being observed, for GFP and TGN46, in 93% of the analyzed images, compared with only 34% of GFP colocalization with the cis-marker GM130.

Ca2+ Handling by trans-Golgi in Intact Cells.

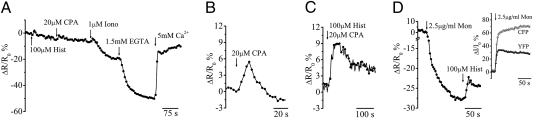

Fig. 2 shows the typical kinetics of the Go-D1cpv fluorescence signal (measured here as ΔR/R0, where ΔR is the change of the YFP/CFP emission intensity ratio at any time, and R0 is the value at the time of the first drug addition) in a HeLa cell expressing Go-D1cpv and subjected to different treatments. Addition of the IP3-generating agonist histamine, which induces a massive Ca2+ release from the ER in these cells (20), resulted in a small, but reproducible transient increase in ΔR/R0. Addition of a specific inhibitor of the SERCA, ciclopiazonic acid (CPA), resulted in a further small and transient increase of ΔR/R0. A large drop of ΔR/R0 was instead caused by addition of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin and the decrease was further augmented by chelation of extracellular Ca2+ with EGTA. Finally, addition of CaCl2 to the medium resulted in a fast and large increase in ΔR/R0 up to a level that was close to the initial value (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Ca2+ handling by the trans-Golgi in intact cells. Unless otherwise indicated, in this and the following figures cells were incubated in mKRB (Methods) and the values are expressed as percentage of normalized ΔR/R0, where ΔR is the change of the emission intensity ratio (at 520/480 nm, excitation 425 nm) at any time, and R0 is the 520/480 value at time of the first drug addition. Due to a slight difference in the photobleaching between CFP and YFP (slightly faster with the latter), with prolonged exposure there is a tendency of the R value (and thus ΔR/R0) to decrease. (A) Representative kinetics of the Go-D1cpv FRET changes in HeLa cells in response to the addition of different stimuli. Where indicated, 100 μM histamine, 20 μM CPA, 1 μM ionomycin, 1.5 mM EGTA, and 5 mM CaCl2 were added. (B–D) ΔR/R0 variation caused by the application of (B) 20 μM CPA alone, (C) 20 μM CPA plus 100 μM histamine, or (D) 2.5 μg/mL monensin followed by 100 μM histamine. The ordinate scale is expanded to better appreciate the effects. (Inset) Kinetics of the emission intensities (expressed as percentage of normalized ΔI/I0) of the CFP (shaded triangles) and YFP (solid triangles) fluorescence, separately, induced by 2.5 μg/mL monensin addition.

CPA, added alone (Fig. 2B) or after histamine (Fig. 2A), caused a rise of [Ca2+] in 90% of the cells analyzed, whereas in the remaining 10% it was without effect. A transient increase in ΔR/R0 was observed when histamine was added in combination with CPA (Fig. 2C). All these changes in ΔR/R0 were due to antiparallel behaviors of CFP and YFP fluorescence (18), as expected for changes in [Ca2+]. It can be noted that a similar small transient increase in ΔR/R0 is present also upon addition of ionomycin, before the large drop in TG [Ca2+]. The explanation for this transient increase, which is not seen if solvent or medium is added to the cells, is that ionomycin is relatively slow at emptying acidic Ca2+ stores (21), whereas it is very efficient at releasing Ca2+ from the ER. Thus, ionomycin will first empty the ER, increasing cytosolic Ca2+ levels that in turn result in an accumulation of Ca2+ by the TG. This rapid accumulation is then followed by a slower emptying of the compartment. This interpretation is supported by the data obtained with monensin (see below).

The effects of histamine and CPA were somewhat surprising, because another GA-localized Ca2+ probe, aequorin (Go-Aeq), had revealed that histamine and SERCA inhibitors cause a major decrease in the [Ca2+] within this organelle (refs. 2, 3, and 5; but see also ref. 22).

The TG luminal pH is known to be acidic (between 6.5 and 5.9) (23, 24). We thus investigated whether the unexpected behavior of Go-D1cpv could be due to an interference of the low pH on the probe response. To increase the organelle pH we treated the cells with monensin that is known to neutralize the pH of acidic organelles. Fig. 2D shows that addition of monensin caused, by itself, a large drop in ΔR/R0. When the fluorescence of the single emission wavelength was analyzed, however, it was noted that monensin caused an increase of both YFP and CFP signals and not, as expected for a change in [Ca2+], an antiparallel behavior of the two signals (Inset in Fig. 2D). Thus, the fast drop in FRET caused by monensin is the result of a change in pH that causes a more marked dequenching of the CFP fluorescence with respect to that of the YFP. Addition of histamine (Fig. 2D) or CPA to monensin-pretreated cells, however, caused, as in controls, small, transient increases of TG [Ca2+], [Ca2+]g, whereas ionomycin induced a rapid [Ca2+]g drop, larger and faster compared with controls, and not anticipated by the small transient ΔR/R0 rise.

To demonstrate that our probe is able to sense reduction in [Ca2+] induced by histamine or CPA when expressed in a subcompartment where the two drug targets (i.e., IP3Rs and SERCA) are present, we take advantage, as a tool, of brefeldin A (BFA), a drug known to block the forward, but not the backward, flow of vesicles in the GA (25). Upon BFA treatment many proteins of the GA move slowly back into the ER and thus it is predicted that also Go-D1cpv should move in that cell compartment (SI Text S1). Indeed, 15 min after BFA application all of the probe is clearly localized only in a delicate reticular struc-ture (ER; Fig. S2A) and, accordingly, the response to histamine (Fig. S2B) and CPA (Fig. S2C) is indistinguishable from that of a bona fide ER Ca2+ probe.

Mechanism of Ca2+ Uptake and Ca2+ Free Concentration in the trans-Golgi.

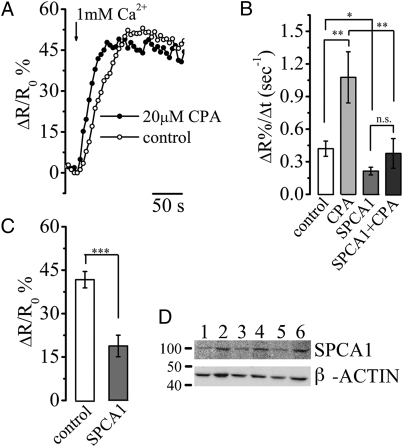

The rise in [Ca2+]g by CPA addition strongly suggests that the TG is devoid of a SERCA-dependent mechanism for Ca2+ uptake. Indeed, the Ca2+ refilling of the TG lumen (as obtained by adding CaCl2 to cells previously depleted of Ca2+) (Methods) was faster in the presence than in the absence of CPA (Fig. 3A). The trans-Golgi Ca2+ uptake rate, with and without CPA, calculated as ΔR%/Δt, was 1.07 ± 0.23 and 0.42 ± 0.07 s−1, respectively (mean ± SEM, n = 9; P < 0.01; Fig. 3B), whereas the average levels of ΔR%/R0 at steady state, reached in the two conditions, were not statistically different (44.50 ± 4.28 for control cells and 42.72 ± 3.56 for CPA-treated cells; n = 9). No significant difference was also observed if the refilling was carried out in the presence of monensin (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Mechanism of Ca2+ uptake in the trans-Golgi. (A) Representative Ca2+ refilling kinetics of the TG in HeLa cells. Where indicated the perfusing Ca2+-free, EGTA-containing medium was changed with the mKRB containing 1 mM CaCl2. The refilling was performed in presence (solid circle) or absence (open circle) of 20 μM CPA. (B) Mean rates of Ca2+ uptake (ΔR%/Δt) as measured in HeLa cells either untreated (control, open bar; 0.42 ± 0.07 s−1) or treated with 20 μM CPA (bar with light shading; 1.07 ± 0.23 s−1), pSUPER-SPCA1 (bar with dark shading; 0.21 ± 0.03 s−1), or pSUPER-SPCA1 and 20 μM CPA (solid bar; 0.38 ± 0.14 s−1). Mean ± SEM, n > 9; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant. (C) TG Ca2+ refilling plateaus (expressed as percentage of ΔR/R0) reached in control (open bar) and SPCA1-interfered HeLa cells (shaded bar) following the protocol described in A. ΔR/R0%, 42 ± 2.8 and 19 ± 3.7 for control and interfered cells, respectively, mean ± SEM, n = 19; ***, P < 0.001. (D) Western blot of HeLa cell extracts visualized with anti-SPCA1 and β-actin antibodies. Lanes 1, 3, and 5 refer to cells transfected with pSUPER-SPCA1 vector and lanes 2, 4, and 6 to cells treated with empty pSUPER vector.

The refilling of Ca2+ in the TG clearly depends on an uptake system other than the SERCA. The best candidate for this activity appears to be the SPCA1 (13). We thus knocked down the expression of endogenous SPCA1 by RNAi, using a specific pSUPER vector system (26). HeLa cells were cotransfected with Go-D1cpv and pSUPER-SPCA1 [for controls, empty pSUPER or pSUPER with an irrelevant RNAi sequence (LacZ)] (Methods). The cotransfection ensures that the cells expressing the Go-D1cpv also take up the pSUPER vectors. A significant reduction in the level of SPCA1 was observed only 56 h after transfection with pSUPER-SPCA1 and reached a maximum after 72 h (a drop of 28 ± 5%, mean ± SEM, n = 6; Fig. 3D). Notably, this reduction reflects the average SPCA1 level of the whole cell population. Considering that the mean transfection efficiency is ~50%, the SPCA1 depletion in the transfected cells should be ~50%.

Using the same Ca2+ depletion/refilling protocol described above, we analyzed the rate and extent of TG Ca2+ uptake at the single interfered cell level. In the majority of the cases (95%), the TG Ca2+ uptake rates (Fig. 3B) and the steady-state levels (Fig. 3C) were substantially reduced, on average, >50%.

To determine the absolute values of [Ca2+] within the TG we used the in vitro calibration procedures described previously for other organelles (27). Given that luminal pH affects the calibration procedure, the TG luminal pH was also determined in intact cells using a null point method (SI Text S2). The luminal pH was found to be 6.74 and the free Ca2+ level 130 μM (Fig. S3). We also tried to determine the percentage of total Ca2+ stored within this subcompartment, calculating indirectly the Ca2+ content of the ER and other Ca2+ stores (SI Text S3 and Fig. S4). By this approach, it was estimated that the TG (and the vesicles endowed with SPCA1) accounts for ~30% of total releasable Ca2+ in HeLa cells and that these compartments represent at least 60% of the total, non-ER Ca2+ stores.

RyR Activation Causes a Drop in [Ca2+]g.

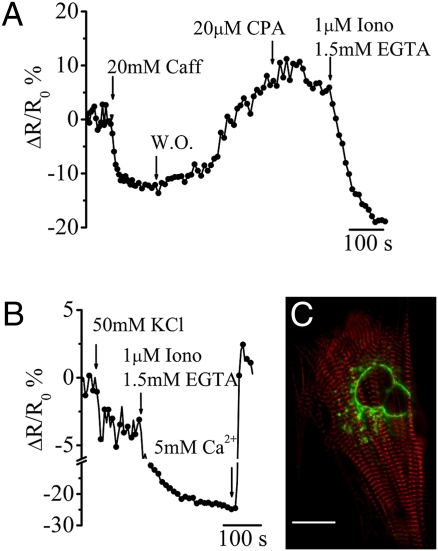

To test whether under physiological conditions the TG can also release Ca2+ upon stimulation, we transfected Go-D1cpv in neonatal cardiac myocytes (Fig. 4C) that, unlike HeLa cells, express high levels of the other major intracellular Ca2+ channel, the RyR (type 2). Addition of caffeine (to open the RyRs) results in a fast, reversible drop of [Ca2+]g (~65% of the [Ca2+]g reduction obtained by ionomycin and EGTA addition; Fig.4A). Also in these cells addition of CPA caused no reduction of [Ca2+]g, but rather, sometimes, a very small rise (Fig. 4A). The cells were then challenged with high K+ (KCl, 30 mM) to trigger Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release response through the RyRs: a small but reproducible decrease in ΔR/R0 was recorded (Fig. 4B). In accordance with these data, the presence of a diffuse intracellular distribution of RyRs in neonatal cardiac cells has been previously reported by immunocytochemistry (28, 29).

Fig. 4.

Ca2+ response by TG in cardiac myocytes upon ryanodine receptor stimulation. (A) Representative kinetics of the ΔR/R0% changes of Go-D1cpv in cardiac myocytes in response to the addition of different stimuli. Where indicated, 20 mM caffeine (Caff), 20 μM CPA, 1 μM ionomycin (Iono), and 1.5 mM EGTA were added through the perfusion system. W.O. indicates a washout of caffeine by mKRB perfusion. ΔR/R0% was induced by caffeine, −17.6 ± 2.1, and CPA, 1.7 ± 2.4; mean ± SEM, n = 7. (B) ΔR/R0% variation caused by the application of 50 mM KCl (−3.86 ± 0.63%; mean ± SEM, n = 5), 5 mM CaCl2, and other stimuli as in A. (C) Confocal merge image of a cardiomyocyte expressing both the Go-D1cpv sensor (green signal, excited at 488 nm) and the mRFP-Zasp construct (red signal, excited at 543 nm). (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

Functional Effects of trans-Golgi Ca2+ Depletion.

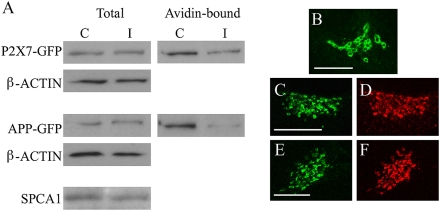

The fact that the TG relies uniquely, as a Ca2+ uptake system, on SPCA1 offers a tool for investigating the importance of TG Ca2+ for classical GA functions, such as protein sorting and processing. HeLa cells were cotransfected with the SPCA1- (or the empty) pSUPER vector together with the cDNA of either the P2X7 purinergic receptor or the amyloid precursor protein, both fused to GFP (P2X7-GFP, ref. 30; APP-GFP, ref. 31). The presence of the two recombinant proteins was then analyzed, by Western blotting, in the total extract and in the biotin/avidin-bound fraction of control and SPCA1-interfered cells (Methods). The RNAi treatment resulted in a 28% mean reduction of the SPCA1 level of the whole cell population (Fig. 3D), corresponding to a reduction in the transfected cells of ~50% (see above). Whereas in control and interfered cells the total expression of the transfected GFP-fused proteins was comparable (100 and 98% for P2X7-GFP expression and 100 and 115% for APP-GFP expression, in control and SPCA1-interfered cells, respectively), a marked reduction (60–80%) of their cell surface exposure was observed upon SPCA1 knockdown (Fig. 5A). Moreover, by the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSVG)-GFP transport assay (32), we observed that SPCA1 down-regulated cells show a slowdown, but not a block, of the ER-Golgi-plasma membrane protein trafficking (SI Text S4 and Fig. S5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of SPCA1 knockdown on cell surface protein exposure and Golgi structure. (A) Western blot analysis of total extract (Total) and biotin/avidin-labeled cell surface protein fraction (Avidin-bound) of control (C) and SPCA1-interfered (I) HeLa cells expressing the recombinant proteins P2X7-GFP and APP-GFP. Specific bands were visualized with different antibodies, as described in Methods. (B–F) Confocal images of HeLa cells expressing (B, C, and E) the Go-D1cpv sensor (excited at 488 nm) or decorated with (D) α-TGN46 or (F) α-GM130 antibody and Alexa-fluor555 conjugated secondary antibody. (B) Control; (C–F) SPCA1-interfered cells. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

Last, but not least, the RNAi protocol caused a marked morphological alteration of the GA (Fig. 5 B–F). Thus, SPCA1 down-regulation causes the loss of the classical cisternae morphology of the TG (Fig. 5B) with the appearance of fragmented, vesicular structures (Fig. 5 C and D). A similar vesicular appearance was surprisingly observed also when the same cells were immunostained with anti-GM130 antibodies (Fig. 5 E and F). On the contrary, almost all of the cells that did not express Go-D1cpv have a normal GA morphology (as revealed by immunostaining with both anti-TGN46 and anti-GM130 antibodies). The perturbation of the GA morphology in SPCA1-depleted cells was further investigated by EM (Fig. S6). Upon SPCA1 reduction, the structure of the Golgi complex/TGN is profoundly altered. Whereas in control cells the stacks of continuous cisternae exhibit the classical shape and the vesicles concentrated mostly at the concavity corresponding to the TGN (Fig. S6 Left), in the knockdown cells the stacks are largely disassembled, many cisternae are fragmented, and numerous vesicles of different size and structure are spread all around in the surrounding cytoplasm (Fig. S6 Right).

Discussion

Information on Ca2+ handling by the GA is relatively recent and, up to now, has been based solely on measurements in cell populations using targeted aequorin. The conclusion has been that the function of the GA in cell Ca2+ handling largely overlaps with that of the ER, classifying the GA as a bona fide, IP3 sensitive, rapidly mobilizable, Ca2+ store (2, 3, 5). Previous studies provided some hints suggesting that the GA situation was, however, more complex and that differences among GA subcompartments may exist (2, 22), but the question has remained unanswered. To directly address this question we constructed a fluorescent Ca2+ probe, targeted to the TG lumen. The main characteristics of this indicator are (i) it is strongly fluorescent and thus it allows monitoring [Ca2+]g at the single-cell level (18); (ii) its affinity for Ca2+ spans a large concentration range, from 0.1–0.2 μM up to several hundred micromoles (18); and (iii) it is selectively localized in the lumen of the TG. As to this latter point, the morphological evidence indicates that (i) the probe and TGN46 are colocalized in practically all of the labeled cisternae, whereas the TGN46 positive small vesicles are almost invariably negative for Go-D1cpv and (ii) there is a substantial difference between the distribution of Go-D1cpv and that of the cis-Golgi marker GM130, although a modest overlapping between the two proteins was observed. Whether this overlapping reflects partial mistargeting of the probe or the incomplete separation between the cis- and the trans-Golgi remains to be established.

The data concerning the control of luminal TG [Ca2+] are clear: (i) Ca2+ uptake in this GA compartment is entirely dependent on SPCA1 activity; paradoxically blockade of the SERCA by CPA increases the rate of TG Ca2+ refilling, probably because of the cytosolic Ca2+ increase caused by the latter drug (that also activates capacitative Ca2+ influx; ref. 33); (ii) IP3 generation by receptor stimulation, and/or pharmacological blockade of the SERCA, slightly increases TG [Ca2+]; (iii) in cells endowed with good expression of RyR2, activation of these channels (by caffeine or Ca2+) causes a substantial drop of the [Ca2+]g. From this point of view, therefore, the TG appears quite unique among organelles: (i) it is insensitive to IP3; (ii) in cells devoid of RyR, it functions as a Ca2+ sink and (iii) it behaves as a mobilizable Ca2+ store when the RyRs are strongly expressed. Notably, the presence of RyRs on the GA of neurons has been previously suggested, on the basis of staining with a fluorescent ryanodine derivative (34).

The question then arises as to why Go-Aeq, which contains the same targeting sequence as Go-D1cpv, responds so differently to IP3 generation and SERCA inhibition (2, 3, 5). We found that, probably because of its much higher level of expression, Go-Aeq is localized in all GA compartments and in some cells substantially retained also in the ER. When indeed HeLa cells were cotransfected with both Go-D1cpv and Go-Aeq constructs and analyzed for a direct comparison of their expression (Fig. S7), a partial mismatch between the Go-Aeq and the Go-D1cpv distribution (Fig. S7 C and D) was observed, as expected if Go-Aeq is not selectively trapped in a specific GA subcompartment. Thus, not only the signal of Go-Aeq is the mean of thousands of cells but also Go-Aeq reports the [Ca2+] from all of the GA compartments; moreover, given the nonlinear dependence of luminescence on the [Ca2+], the overall Aeq signal is intrinsically dominated by the compartments with highest [Ca2+] and largest changes in [Ca2+] (35) and thus by the signal coming from the cis- and intermediate-Golgi regions.

The present data provide additional information on the functional role of TG Ca2+. In particular, recent evidence suggests that SPCA1 down-regulation (in cell culture or in knockout animals) affects a number of cellular and GA-specific functions, from GA morphology to apoptosis and from neuronal differentiation to protein trafficking (13, 36–39). Here we have further expanded this analysis by acutely down-regulating SPCA1 expression using the RNAi technique. The first conclusion is that the turnover of SPCA1 is relatively slow, because a significant reduction in the level of the protein can be detected only 56 h after transfection. Second, a reduction in ~50% of the SPCA1 results in major functional and structural alteration of the GA: (i) a dramatic modification in the morphology of the whole organelle, with the disappearance of the flattened cisternae replaced by vesicular convoluted structures; (ii) a major reduction in the sorting to the plasma membrane of two transfected proteins, the purinergic receptor P2X7-GFP and the transmembrane protein APP-GFP; and (iii) using the classical VSVG-GFP temperature-sensitive mutant assay, we observed a retardation both of the accumulation of the viral protein in the GA and in its transfer to the plasma membrane.

As to these latter effects, two aspects are worth stressing: (i) SPCA1 is expressed not only in the TG but also in the vesicle of the secretory pathways and accordingly, strictly speaking, it remains to be determined whether the reported alterations in sorting and processing depend on modifications of processes that occur in the TG or in the secretory vesicles or both; (ii) the major functional and structural alterations reported above are observed with only ~50% reduction, on average, of the SPCA1 expression, suggesting the major relevance of the Ca2+ content for the proper functioning of the organelles in the secretory pathway. In this context it is worth mentioning that a mutation in one allele for SPCA1 in humans is responsible for a major alteration in keratinocyte functions, Hailey–Hailey disease (11–13, 37, 38).

In conclusion, we here report the direct monitoring of the [Ca2+] selectively within the TG of live cells and we demonstrate that its Ca2+ handling mechanism is quite unique. The TG appears devoid of IP3 receptors, but houses, at least in cardiac myocytes, RyRs. Ca2+ uptake is solely dependent on the expression of SPCA1 whereas the SERCA is excluded from this GA subcompartment. Thus, the luminal Golgi Ca2+ concentration is a dynamic parameter that may increase or decrease during cell life, depending on the specific pattern of intracellular Ca2+ channels expressed and on the dynamics of cytosolic Ca2+. Remarkably, the maintenance of the Ca2+ content provided by SPCA1 appears essential for the correct structure of the entire GA and for important functions of the secretory pathway.

Methods

Constructs.

The targeting sequence of the trans-Golgi enzyme sialyl-transferase (MIHTNLKKKFSCCVLVFLLFAVICVWKEKKKGSYYDSFKLQTKEFQVLKSLGKLAMGSDSQSVFSSSTQ) was introduced before the start codon of the D1cpv cDNA (kindly provided by R. Tsien) in the HindIII restriction site, after its isolation from the Go-Aeq construct (2). The pSUPER-SPCA1 vector used for the RNAi experiments was kindly provided by F. Wuytack (26). The cDNA coding for P2X7-GFP (30) was helpfully made available by F. Di Virgilio. The mRFP-Zasp contruct (40) was kindly provided by M. Zaccolo and the ts045 VSVG-GFP plasmid by N. Borgese.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

HeLa cells were grown and transfected as previously described (41).

For RNAi experiments, the amount of DNA was 4 μg [with a ratio for Go-D1cpv (or P2X7-GFP or APP-GFP):pSUPER (empty, aspecific, or SPCA1 specific) of 1:7] and the analyses were carried out 72 h after transfection. For RNAi experiments, SPCA1 knockdown cells were always compared with mock or pSUPER-LacZ transfected controls.

Primary cultures of cardiac ventricular myocytes from 1- to 3-day-old Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories) were prepared, maintained, and transfected as described (42).

Cell Imaging.

Cells expressing the fluorescent probe were analyzed, 24–48 h after transfection, as described by Drago et al. (41). For time-course experiments, the fluorescence intensity was determined over regions of interest covering the GA. Exposure time and frequency of image capture varied from 300 to 800 ms and from 0.2 to 0.05 Hz, respectively, depending on the intensity of the fluorescent signal of the cells analyzed and on the speed of fluorescence changes.

Cells were mounted into an open-topped chamber thermostated at 37 °C and maintained in an extracellular medium [modified Krebs–Ringer Buffer (mKRB) containing 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM Mg2Cl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), at 37 °C]. For pH determination and Go-D1cpv calibration, an intracellular-like medium was used [130 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM succinic acid, and 20 mM Pipes (pH 6.74), at 37 °C].

The refilling protocol was performed essentially as described by Pinton et al. (2).

Immunocytochemistry.

Cells were treated as previously described (41), using the following antibodies: mouse anti-GM130 (BD Bioscience Pharmingen), sheep anti-TGN46 (AbD Serotec MorphoSys), mouse anti-HA (12CA5; Roche Applied Science), and Alexa Fluor 555 (or 488) conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-sheep IgG (Molecular Probes Invitrogen). Images were collected with a Bio-Rad 2100MP confocal system by using the Arg-488-nm laser line (Alexa Fluor 488 and Go-D1cpv) and He-Ne 543-nm laser line (Alexa Fluor 555 and mRFP-Zasp). For additional information see SI Methods. Colocalization analysis for Go-D1cpv and cis/trans-Golgi markers was performed on Z-stacks with the Intensity Correlation Analysis plug-in (Tony Collins, Wright Cell Imaging Facility, Toronto, ON, Canada). Z-stacks were acquired with a step of 0.5 μm.

Biotin/Avidin Cell Surface Protein Labeling and Western Blot Analysis.

Seventy-two hours after transfection, cells were treated as described by Gastaldello et al. (43). Proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE, blotted onto a PVDF membrane, and probed with selected antibodies [rabbit polyclonal anti-SPCA1(PMR1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (Abcam), and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (Sigma).

Materials.

CPA, digitonin, histamine, and monensin were purchased from SIGMA-Aldrich; ionomycin was from Calbiochem. All other materials were analytical or highest available grade.

Statistical Analysis.

All of the data are representative of at least five different experiments. Data were analyzed by Origin 7.5 SR5 (OriginLab Corporation). Averages are expressed as mean ± SEM (n, number of independent experiments; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; unpaired Student's t test).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Drago, G. Ronconi, and M. Santato for performing some of the experiments and technical assistance. We thank R. Tsien (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA) for the cDNA coding for D1cpv, F. Wuytack for the pSUPER vectors, M. Zaccolo (University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK) for the mRFP-Zasp contruct, F. DiVirgilio (University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy) for the cDNA coding for P2X7-GFP, and N. Borgese (University of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy) for the ts045 VSVG-GFP plasmid. We are grateful to J. Meldolesi, C. Fasolato, D. Sandonà, and P. Magalhães for useful suggestions. This work was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific Research (to P. Pizzo and T.P.); by FIRB (Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base) Grant RBIN042Z2Y (to P. Pizzo); and by the Veneto Region (Biotech 2), the Italian Institute of Technology, the Strategic Projects of the University of Padua, and the CARIPARO (Cassa di Risparmio di Padova e Rovigo) Foundation (T.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1004702107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Keller P, Simons K. Post-Golgi biosynthetic trafficking. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:3001–3009. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.24.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinton P, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R. The Golgi apparatus is an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive Ca2+ store, with functional properties distinct from those of the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 1998;17:5298–5308. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Missiaen L, et al. Calcium release from the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum in HeLa cells stably expressing targeted aequorin to these compartments. Cell Calcium. 2004;36:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolman NJ, et al. Stable Golgi-mitochondria complexes and formation of Golgi Ca(2+) gradients in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15794–15799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanoevelen J, et al. Cytosolic Ca2+ signals depending on the functional state of the Golgi in HeLa cells. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pezzati R, Bossi M, Podini P, Meldolesi J, Grohovaz F. High-resolution calcium mapping of the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi-exocytic membrane system. Electron energy loss imaging analysis of quick frozen-freeze dried PC12 cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1501–1512. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson HW, Rhodes CJ, Hutton JC. Intraorganellar calcium and pH control proinsulin cleavage in the pancreatic beta cell via two distinct site-specific endopepti-dases. Nature. 1988;333:93–96. doi: 10.1038/333093a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carnell L, Moore HP. Transport via the regulated secretory pathway in semi-intact PC12 cells: Role of intra-cisternal calcium and pH in the transport and sorting of secretogranin II. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:693–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin CD, Shields D. Prosomatostatin processing in permeabilized cells. Calcium is required for prohormone cleavage but not formation of nascent secretory vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1194–1199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan JS, Burgoyne RD. Characterization of the effects of Ca2+ depletion on the synthesis, phosphorylation and secretion of caseins in lactating mammary epithelial cells. Biochem J. 1996;317:487–493. doi: 10.1042/bj3170487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Z, et al. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat Genet. 2000;24:61–65. doi: 10.1038/71701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behne MJ, et al. Human keratinocyte ATP2C1 localizes to the Golgi and controls Golgi Ca2+ stores. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:688–694. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Missiaen L, Dode L, Vanoevelen J, Raeymaekers L, Wuytack F. Calcium in the Golgi apparatus. Cell Calcium. 2007;41:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mellman I, Simons K. The Golgi complex: In vitro veritas? Cell. 1992;68:829–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90027-A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polishchuk RS, Mironov AA. Structural aspects of Golgi function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:146–158. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3353-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breton C, Mucha J, Jeanneau C. Structural and functional features of glyco-syltransferases. Biochimie. 2001;83:713–718. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Matteis MA, Luini A. Exiting the Golgi complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer AE, et al. Ca2+ indicators based on computationally redesigned calmodulin-peptide pairs. Chem Biol. 2006;13:521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyawaki A, et al. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature. 1997;388:882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montero M, et al. Ca2+ homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum: Coexistence of high and low [Ca2+] subcompartments in intact HeLa cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:601–611. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.3.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fasolato C, Pozzan T. Effect of membrane potential on divalent cation transport catalyzed by the “electroneutral” ionophores A23187 and ionomycin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19630–19636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanoevelen J, et al. Inositol trisphosphate producing agonists do not mobilize the thapsigargin-insensitive part of the endoplasmic-reticulum and Golgi Ca2+ store. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seksek O, Biwersi J, Verkman AS. Direct measurement of trans-Golgi pH in living cells and regulation by second messengers. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4967–4970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.4967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llopis J, McCaffery JM, Miyawaki A, Farquhar MG, Tsien RY. Measurement of cytosolic, mitochondrial, and Golgi pH in single living cells with green fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6803–6808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doms RW, Russ G, Yewdell JW. Brefeldin A redistributes resident and itinerant Golgi proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:61–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Baelen K, et al. The contribution of the SPCA1 Ca2+ pump to the Ca2+ accumulation in the Golgi apparatus of HeLa cells assessed via RNA-mediated interference. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306:430–436. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00977-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudolf R, Magalhães PJ, Pozzan T. Direct in vivo monitoring of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ and cytosolic cAMP dynamics in mouse skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:187–193. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seki S, et al. Fetal and postnatal development of Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ sparks in rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:535–548. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guatimosim S, et al. Nuclear Ca2+ regulates cardiomyocyte function. Cell Calcium. 2008;44:230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morelli A, et al. Extracellular ATP causes ROCK I-dependent bleb formation in P2X7-transfected HEK293 cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2655–2664. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-04-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Florean C, et al. High content analysis of gamma-secretase activity reveals variable dominance of presenilin mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:1551–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Presley JF, et al. ER-to-Golgi transport visualized in living cells. Nature. 1997;389:81–85. doi: 10.1038/38001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Putney JW, Jr, Broad LM, Braun FJ, Lievremont JP, Bird GS. Mechanisms of capacitative calcium entry. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2223–2229. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.12.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cifuentes F, et al. A ryanodine fluorescent derivative reveals the presence of high-affinity ryanodine binding sites in the Golgi complex of rat sympathetic neurons, with possible functional roles in intracellular Ca(2+) signaling. Cell Signal. 2001;13:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montero M, Barrero MJ, Alvarez J. [Ca2+] microdomains control agonist-induced Ca2+ release in intact HeLa cells. FASEB J. 1997;11:881–885. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.11.9285486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okunade GW, et al. Loss of the Atp2c1 secretory pathway Ca(2+)-ATPase (SPCA1) in mice causes Golgi stress, apoptosis, and midgestational death in homozygous embryos and squamous cell tumors in adult heterozygotes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26517–26527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aberg KM, Racz E, Behne MJ, Mauro TM. Involucrin expression is decreased in Hailey-Hailey keratinocytes owing to increased involucrin mRNA degradation. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1973–1979. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aronchik I, et al. Actin reorganization is abnormal and cellular ATP is decreased in Hailey-Hailey keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:681–687. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sepúlveda MR, Vanoevelen J, Raeymaekers L, Mata AM, Wuytack F. Silencing the SPCA1 (secretory pathway Ca2+-ATPase isoform 1) impairs Ca2+ homeostasis in the Golgi and disturbs neural polarity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12174–12182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2014-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Benedetto G, et al. Protein kinase A type I and type II define distinct intracellular signaling compartments. Circ Res. 2008;103:836–844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.174813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drago I, Giacomello M, Pizzo P, Pozzan T. Calcium dynamics in the peroxisomal lumen of living cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14384–14390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaccolo M, Pozzan T. Discrete microdomains with high concentration of cAMP in stimulated rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. Science. 2002;295:1711–1715. doi: 10.1126/science.1069982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gastaldello S, et al. Inhibition of proteasome activity promotes the correct localization of disease-causing alpha-sarcoglycan mutants in HEK-293 cells constitutively expressing beta-, gamma-, and delta-sarcoglycan. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:170–181. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.