Abstract

We surveyed young American men traveling to Tijuana, Mexico, from San Diego, California, for a weekend night out, collecting responses both southbound at the outset of the evening and northbound upon return at the end of the evening. Among 650 males, we examined the relationship between sexual histories and attitudes and alcohol use, both historically and on their night in Tijuana. Respondents with a history of coercing sex drank more in Tijuana and were more likely to binge drink. Although estimating sexual assaults committed by these males on the evening in question was not possible, this research establishes the link between a history of sexual assault and the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of young men resulting from an evening in a timeout environment.

Keywords: sex offense history, alcohol drinking, males

Introduction

The estimated annualized rate of attempted or completed rape among college women in 1996 was 4.9%, or 1 in 20 women (Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2000), and males are almost universally the perpetrators of female rape (99.6%) and of male rape (85.2%) (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). For college women, most sexual assaults occur in bars, nightclubs, or off-campus residences (Fisher et al., 2000). Environments that provide easy access to alcohol and a timeout atmosphere increase the risk of illicit sexual behavior and potential violence (Listiak, 1974). Bars and other similar environments compound the risks of sexual victimization by increasing exposure to risks and by contributing to the alcohol impairment of potential victims (Parks & Miller, 1997). As many as one in five women experience alcohol-related sexual assaults, and their risk of such assaults increases seven-fold if they report themselves as binge drinking (Howard, Griffin, & Boekeloo, 2008). Drinking games are often perceived as a prelude to sexual activity, although there may be gender differences between sexual activity as an outcome and the role of sexual expectations and consumption (Johnson & Stahl, 2004).

Alcohol is commonly a factor in sexual assault incidents either in terms of victims’ or offenders’ consumption or both (Abbey, 2002). In 66.6% of female rapes and 58.5% of male rapes, the offender was using drugs or alcohol (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). Men who are drinking heavily at the time of a sexual assault differ from light drinkers and nondrinkers in their misinterpretations of the victim’s signals, their manipulative behavior, the physical force applied, and the severity of the assault (Parkhill, Abbey, & Jacques-Tiura, 2009). The consistent correlation between greater alcohol consumption and sexual assault by males may simply reflect that heavier drinkers are also likely to be drinking in dating or other sexually charged situations (Abbey, Zawacki, Buck, Clinton & McAuslan, 2001). Other potential mechanisms include the use of alcohol as an excuse for sexual assault and/or underlying social inhibitions that drive both behaviors (Zawacki, Abbey, Buck, McAuslan, & Clinton-Sherrod, 2003).

Alcohol may also influence male and female sexual expectations somewhat differently (Wilsnack, 1991; Jacques-Tiura, Abbey, Parkhill, & Zawacki, 2007). Research with adolescents aged 13 to 19 suggests that males have a stronger association with sexual risk-taking and sexual disinhibition than females, whereas both males and females expressed an expected association between alcohol and sexual enhancement (Dermen & Cooper, 1994a, 1994b). Perversely, the expectation of alcohol being associated with sexual risks may lead to a greater incidence of sexual intercourse rather than having a protective effect (Dermen, Cooper, & Agocha, 1998).

Beliefs that alcohol affects other people’s sexual interests and behavior are commonly documented (Abbey et al., 2001). Alcohol also distorts the cognitive processes by which individuals evaluate cues from potential partners, a distortion that may be compounded for past perpetrators of sexual assault (Abbey, Zawacki, & Buck, 2005). Researchers have documented that attitudes about stereotypical sex roles and acceptance of rape mythology (Burt, 1980) is associated with males’ misperception of female sexual availability (Jacques-Tiura et al., 2007). Male confusion over sexual signals may derive from insensitivity to a woman’s intended signals or a personal bias as to what social behavior or dress indicates regarding sexual availability. Male attitudes about rape (as measured through the Rape Myth Acceptance scale) have been found to be associated with limited sensitivity to social cues about sexual interest or availability, thus compounding the risk of sexual coercion (Farris & Viken, 2006).

In sum, alcohol may be a conduit to sexual assault through numerous mechanisms, such as distorting interpretation of social interaction, serving as an a priori or post facto excuse for an assault, or a belief that the relationship between alcohol use and sexual activity is normative. Confounding factors include attitudes towards women and about rape and underlying characteristics that would drive both alcohol use and sexual assault.

Although drinking history has been associated to current drinking levels and subsequently to current sexual assault, the possibility that a history of sexual assault could also be associated to current drinking and subsequent current sexual assault has been understudied. In other words, it may be possible that, independent of drinking history, males with a history of sexual assault would be more likely to exhibit a heavy consumption of alcohol as a conduit for sexual experiences and assault. In this study, we evaluated the first part of this intriguing two-part hypothesis: that a history of sexual assault may be associated with current heavy drinking, which in turn may contribute to current sexual assault. Using a convenience sample of young men in an alcohol-rich environment, we examined the historical behavior of individuals as it relates to evening drinking. We studied the association between evening drinking and sexual assault histories, using an objective measure of drinking for a sample of college-age males.

Methods

Sample

This study uses data from 650 males in a convenience sample collected from November 2006 to December 2008 at the San Diego, California, border with Tijuana, Mexico. The sample was drawn as part of a study of female victimization that developed and tested a group protective intervention. Randomly selected groups with at least one female member who were traveling across the border from San Diego to visit Tijuana were surveyed crossing southbound on random weekend evenings and then upon their return, crossing northbound. The sampling procedure has been described in detail elsewhere (Kelley-Baker, Mumford, Vishnuvajjala, Voas, & Romano, 2008, December 1). The data collection instruments and methods were reviewed and approved by the IRB of the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation. Southbound measures were collected via a paper-and-pencil survey while northbound measures were collected both via self-response paper-and-pencil (including the SES items) and via a PDA (handheld personal digital assistant) interview administered by project staff, allowing also for observation of respondent behavior. Between 9 p.m. and 1 a.m. on randomly selected weekend nights, interviewers randomly approached groups of 2 to 8 individuals which included at least one female appearing to be under age 25. Participant anonymity was maintained at each stage of the process. Upon completion of the northbound interview (the northbound surveys were administered between 12 a.m and 6 a.m.), interviewers provided each participant with a $20 gift card, which was noted at the initial approach as an incentive for participation. Survey staff recorded observations (gender, estimated age, and group size) of those who were approached but refused the opportunity to participate. Male respondents ranged in age from 16 to 46, but 95% of them were between the ages of 18 and 26. Sixty-four percent were younger than 21, the legal drinking age in California.

Measures

Measures were collected as the young men entered Mexico (southbound) and northbound when they returned to the United States after patronizing the Mexican drinking establishments. The focus of this study is the association between respondents’ history of sexual assault and their level of alcohol consumption as measured by their blood alcohol concentration (BAC) when returning to California northbound from Tijuana. Particularly, we were interested in understanding the relationship between individuals’ sexual assault histories—whether they had ever coerced another individual to have sex—and their level of evening drinking. Sexual assault histories, also collected in the northbound survey, reflect responses to four questions derived from the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss & Oros, 1982): (1) Have you ever been in a situation where you became so sexually aroused that you could not stop yourself even though the person didn’t want to have sex? (2) Have you ever persuaded someone to have sexual intercourse with you by giving her drugs or alcohol? (3) Have you ever persuaded someone to have sexual intercourse with you when she didn’t really want to by pressuring her with continual arguments? (4) Have you ever been in a situation where you used some degree of physical force (twisting an arm, holding down, etc.) to try to make a person engage in kissing or petting when they didn’t want to? Unfortunately, 70% of respondents did not answer the fourth item, regarding use of physical force in a sexual situation, rendering this item unusable for analysis. Respondents who answered yes to at least one of the first three questions were coded 1 for sexual assault history, and respondents answering in the negative to each of the same three questions were coded 0.

The border survey also includes measures of evening sexual behavior, referring to sexual dancing, kissing and petting, fondling, and sexual intercourse, recorded northbound when respondents were returning to San Diego from Tijuana. Responses to these items were limited by sample size, in that queries at the border were subsequently removed from the northbound survey and replaced by questions in a followup Web survey (data not reported in this paper). These data are reported for descriptive purposes in the Results section but are not included in multivariate models. The rare incidence of personally committing sexual assault while in Tijuana is reported in our Results as well.

These data provide an objective measure of respondents’ alcohol consumption during the evening, with a measure of the individual’s BAC taken both southbound and northbound with a handheld SD-400 Intoxilyzer manufactured by MPI/CMI. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2007) defines binge drinking as “a pattern of drinking alcohol that brings blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08 gram-percent or higher. For a typical adult, this pattern corresponds to consuming 5 or more drinks (male), or 4 or more drinks (female), in about 2 hours.” In this study, we examined both the continuous data on respondent BAC and a dichotomous variable termed “evening binge drinker” for those individuals whose northbound BACs were measured as 0.08 or higher.

The central relationship between sexual assault history and evening drinking is examined in the context of the histories, attitudes, and behaviors of the respondents. We examined their history of sexual behavior and, in the context of both their drinking history and alcohol consumption on the evening of the border survey, their attitudes about alcohol’s effect on other people—whether other people were believed to be more fun or more sexually available when drinking alcohol. History of violence was measured in the southbound survey by three items that referred to lifetime instances: ever violent while under the influence of drugs, ever beaten another person, or ever used a weapon against another person. History of victimization was likewise represented by three items that measured instances in the 12 months before the southbound interview: ever been verbally threatened, ever been physically assaulted, and ever been threatened by with a weapon.

Respondents’ history of alcohol use, also collected in the southbound survey, was measured several ways. We examined their past month frequency of drinking (frequent drinkers defined as those who had one or more alcoholic beverages at least 3 days per week, coded as 1, and less frequent drinkers coded 0). Recent binge drinkers (coded 1) who reported having consumed five or more alcoholic beverages (consistent with the NIAAA’s correspondence of the number of alcoholic beverages a male would typically consume in a pattern of binge drinking) on at least one occasion in the past month were also examined. Respondents’ southbound BACs were measured at intake to the study, as they crossed the border from San Diego to Tijuana.

Respondents’ age was examined as a continuous variable. Because preliminary bivariate analyses indicate that differences in evening drinking behavior by race/ethnicity represented differences between White non-Hispanics and other racial/ethnic groups, we used multivariate models as an indicator for White race/ethnicity. Participants who had previously visited Tijuana were expected to be more aware of the environment they were entering and thus to have a more accurate perception of both the opportunities and the potential risks they would face. However, preliminary bivariate analyses examining respondents’ history of visiting Tijuana in the past year and the past month found this characteristic to be consistently unrelated to respondents’ history of sexual coercion and evening BAC measured as they returned northbound.

Four additional questions about evening sexual behavior (sexual dancing, petting/kissing, fondling, sexual intercourse) were initially included in the border survey (through March 2008); however, these questions were subsequently removed from the northbound border survey. These variables were examined for descriptive purposes but because of the level of missing data, they are not included in multivariate analyses. The incidence of these male respondents committing sexual assault while in Tijuana is presented with our Results but further analysis of these rare self-reports was not possible.

Data Analysis

The sample was restricted to male participants who responded to the northbound social experiences survey as they returned from Mexico to California. We present a univariate description of this sample’s demographics and selected historical experiences, followed by a bivariate description of participants’ sexual history, attitudes, and behavior according to whether they have reported a history of committing sexual assault. We used chi-square tests of significance to test the association between self-reported sexual assault histories and selected characteristics. Linear regression was used to predict the values of the male respondents’ BAC levels. Logistic regression was used to predict the probability of the male respondents’ being evening binge drinkers (BAC≥0.08) upon their return from Tijuana. The multivariate models account for the nonindependence of individual respondents based on their recruitment as previously formed peer groups at the border. Finally, in that we hypothesize a relationship between binge drinking and sexual assaults, we investigated the potential interaction of individual histories of sexual assault and of recent binge drinking in examining evening drinking behavior. To avoid inflating the risk of a Type I error arising from the nonindependence of observations, all tests of hypotheses were conducted using generalized estimation equations in STATA 9.0, with “peer group” included as a random variable. By this method, we were able to account for the correlation of error structures between peers self-selecting into a “peer group”; further reading in this area may be done in Hardin, James; Hilbe, Joseph (2003). In that these analyses use data originally collected for other purposes, it was also necessary to control for a brief intervention targeting females (which discouraged overconsumption of alcohol, the outcome measure of this study) delivered to randomly selected groups at entry into the study.

Results

Sample Description

The mean age of the male sample selected for this study was 20.5 (Table 1), and the majority (61.7%) self-reported themselves to be Hispanic. In terms of drinking history, nearly a third of the sample (30.5%) had experienced at least one binge-drinking incident in the past month, and a similar proportion (29.1%) were frequent drinkers in the prior month. Most respondents measured at a low BAC (mean BAC=0.01) at southbound border entry into the study. However, one in five respondents (20.2%) started the evening with a BAC measure of 0.01 or greater; of these early evening drinkers, a quarter (4.5% of total) were already binge drinking (BAC≥0.08; data not shown in Table 1). Four of five respondents had been to Tijuana at least once in the past year, three-quarters of those in the past month.

Table 1.

Sample Description, Males

| N=650 | N | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 650 | ||

| Ages 16–20 | 417 | 64.2 | |

| Ages 21 and older | 233 | 35.9 | |

| Mean age (s.d.) | 650 | 20.5 (3.0) | |

| Race/ethnicitya | 650 | ||

| Hispanic | 401 | 61.7 | |

| White | 101 | 15.5 | |

| Black | 80 | 12.3 | |

| Other | 68 | 10.5 | |

| Alcohol use | |||

| Frequent drinker (3+days/week past month) | 650 | 189 | 29.1 |

| Recent binge drinker | 647 | 198 | 30.5 |

| Mean southbound BAC (s.d.) | 645 | 646 | 0.01 (.034) |

| History of visiting Tijuana | 650 | ||

| First visit | 112 | 17.2 | |

| 1+ in past year (first this month) | 131 | 20.2 | |

| 1+ in past month | 407 | 62.6 | |

| History of victimization (past year) | |||

| Ever been verbally threatened | 650 | 302 | 46.5 |

| Ever been physically assaulted | 650 | 220 | 33.9 |

| Ever been threatened by with a weapon | 650 | 149 | 22.9 |

| History of violence | |||

| Ever become violent on drugs | 649 | 188 | 28.9 |

| Ever beaten another person | 649 | 173 | 26.6 |

| Ever used weapon against another person | 648 | 80 | 12.3 |

| Sexual assault historyb | |||

| Ever been so sexually aroused that couldn’t stop yourself although partner uninterested in sex | 635 | 61 | 9.4 |

| Ever persuaded someone to have sex by giving them drugs or alcohol | 640 | 51 | 7.9 |

| Ever persuaded someone to have sex by pressuring with continual arguments | 640 | 46 | 7.1 |

All respondents self-identifying as Hispanic are coded as Hispanic, regardless of other race/ethnicity information presented. Thus, no respondents coded otherwise are also Hispanic.

Sexual assault histories were collected in the northbound survey; all other characteristics presented here were collected in the southbound survey.

Over a quarter of the sample had ever become violent while under the influence of alcohol or drugs (28.9%) or had ever beaten another person (26.6%). Far fewer (12.3%) reported having ever used a weapon against another person. A slightly greater proportion of respondents (14.7%) self-reported having ever committed sexual assault on another person, a composite of the three sexual assault history items shown in Table 1. Nine percent of the sample reported having “ever been so sexually aroused that [he] couldn’t stop [himself] although [his] partner didn't want to have sex.” The prevalence of other measures was lower, with 7.9% having ever persuaded someone to have sex by giving her drugs or alcohol, and 7.1% admitting to having ever persuaded someone to have sex by pressuring her with continual arguments.

Greater percentages reported incidents in which they themselves were the victims of violence. Nearly half (46.5%) reported having been verbally threatened and nearly a third (33.9%) reported having been physically assaulted in the past year. Almost twice as many respondents reported having been threated with a weapon (22.9%) as the proportion who reported having threatened someone else with a weapon (12.3%).

Participants with a History of Sexual Assault

There were significant differences in sexual history and attitudes between those male participants who admitted to having committed sexual assault in the past (14.7%) and those who denied a history of sexual assault (Table 2). Respondents who had ever coerced sex were significantly more likely to report having experienced sex by mutual consent (odds ratio (OR) =1.8; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.1,3.0) but also to report having misinterpreted the signals of a sexual partner (OR=6.3; 95%CI=3.5,11.2). Individuals with a history of sexual assault were more likely to believe that people who drink alcohol are more relaxed and fun to be with (OR=2.4; 95%CI=1.5,4.0) and to believe that people who drink are more sexually available (OR=2.0; 95%CI=1.2,3.3).

Table 2.

Sexual History, Attitudes, and Behavior by History of Sexual Assault, Males

| Total | No History of Coerced Sex | Ever Coerced Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=650 | n | 634 | 541 | 93 | |

| Personal Sexual History | 85.3% | 14.7% | |||

| Ever experienced sexual intercourse by mutual consent | 629 | n % |

411 65.3 |

342 63.6 |

69 * 75.8 |

| Ever misinterpreted partner’s level of sexual interest | 423 | 101 23.9 |

66 18.2 |

35 *** 58.3 |

|

| Attitudes about People who Drink | |||||

| People who drink alcohol are more relaxed and fun to be with | 630 | 346 54.9 |

280 52.0 |

66 *** 72.5 |

|

| People who drink are more sexually available | 629 | 389 61.8 |

321 59.7 |

68 ** 74.7 |

|

| History of Victimization (past year) | |||||

| Ever been verbally threatened | 631 | 298 47.2 |

240 44.6 |

58 ** 62.4 |

|

| Ever been physically assaulted | 632 | 218 34.5 |

181 33.5 |

37 40.2 |

|

| Ever been threatened by with a weapon | 629 | 148 23.5 |

109 20.3 |

39 *** 41.9 |

|

| History of Violence | |||||

| Ever become violent on drugs | 633 | 187 29.5 |

142 26.3 |

45 *** 48.4 |

|

| Ever beaten another person | 633 | 172 27.2 |

131 24.3 |

41 *** 44.1 |

|

| Ever used weapon against another person | 632 | 80 12.7 |

55 10.2 |

25 *** 26.9 |

|

| Evening Sexual Behavior | |||||

| Dance sexually with someone | 425 | 271 63.8 |

228 62.6 |

43 70.5 |

|

| Engaged in kissing or petting with someone | 420 | 167 39.8 |

133 36.8 |

34 ** 57.6 |

|

| Fondled someone | 412 | 121 29.4 |

93 26.1 |

28 *** 50.0 |

|

| Had sexual intercourse with someone | 440 | 27 6.1 |

9 2.4 |

18 *** 28.6 |

|

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Respondents’ history of victimization and history of violence were associated with their history of sexual assault. Individuals with a history of sexual assault were more likely to report past year incidents of having been verbally threatened (OR=2.1; 95%CI=1.3,3.2) and having been threatened with a weapon (OR=2.8; 95%CI=1.8,4.5). Reflecting the oftentimes reciprocal nature of violence, respondents with a history of sexual assault were also more likely to report lifetime incidents of having become violent while on drugs (OR=2.6; 95%CI=1.7,4.1), having beaten another person (OR=2.5; 95%CI=1.6,3.9), and having threatened someone with a weapon (OR=3.2; 95%CI=1.9,5.5).

The measures of evening sexual behavior provide preliminary descriptions in that responses were collected from approximately two-thirds of the sample. In the portion of the sample that was questioned about evening sexual behavior, although dancing sexually with someone was an activity common to both those with a sexual assault history and those without, individuals who reported having ever coerced sex were more likely to engage in kissing or petting with someone (OR=2.3; 95%CI=1.3,4.1), to have fondled someone (OR=2.8; 95%CI=1.6,5.0), and to have had sexual intercourse with someone (OR=16.4; 95%CI=6.9,38.6) during their evening in Tijuana.

Reports of personally committing sexual assault while in Tijuana were so rare that they were excluded from analysis beyond the incidence reported here (data not shown in table). Two individuals who had admitted that they had ever been so aroused that they couldn’t stop themselves although their partners were uninterested in sex reported that they had experienced such an incident while in Tijuana. No respondents reported using drugs to persuade a partner to have sex in Tijuana. One respondent reported having pressured a sexual partner through continual arguments in Tijuana. Thirteen reported having had oral sex by mutual consent in Tijuana, but no respondent reported having forced sex that evening in Tijuana.

Sexual Assault History as a Predictor of Evening Drinking

The relationship between evening drinking and history of sexual assault was confirmed by multivariate models, adjusting for respondents’ histories of consensual sex, drinking, and violence, attitudes about people who drink, and demographic characteristics. In a model of direct effects (Table 3, model 1), a history of sexual assault predicted evening drinking (β=0.015; 95%CI=.003,.03). That is, individuals who reported having sexually assaulted someone in the past drank more during their evening in Tijuana. This relationship is adjusted for respondents’ reports of having experienced sex by mutual consent in the past, which by contrast is inversely associated with evening drinking.

Table 3.

Multivariate Models of Evening Drinking, Northbound Measure

| Mean BAC | Binge Drinker | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n=605 | Model 1 Direct Effects | Model 2 Interaction | Model 3 Interaction |

| β | β | β | |

| History of sexual assault [95% confidence interval] | 0.0125 * [.003,.03] | 0.039 ** [.014,.065] | 2.18 *** [1.16,3.20] |

| Recent binge drinker | 0.021 *** [.011,.031] | 0.024 *** [.014,.034] | 1.40 *** [.80–2.01] |

| Recent binge * sexual assault | ---- | −0.031 * [−.059, −.002] | −1.64 ** [−2.77, −.51] |

| Frequent drinker | 0.014 ** [.004,.023] | 0.014 ** [.004,.023] | 0.56 ** [.17,.95] |

| Southbound BACa | 0.363 *** [.255,.471] | 0.364 *** [.256,.471] | 7.44 [−1.82,16.7] |

| History of sex by mutual consent | −0.018 *** [−.026, −.009] | −0.018 *** [−.026, −.009] | −0.74 *** [−1.12, −.35] |

| Expectation of drinkers’ levity | 0.006 [−.026,.015] | 0.006 [−.002,.014] | 0.18 [−.20,.57] |

| History of violence on drugs | 0.007 [−.002,.016] | 0.007 [−.002,.016] | 0.22 [−.17,.60] |

| Age (continuous) | 0.000 [−.001,.001] | 0.000 [−.001,.002] | 0.02 [−.04,.08] |

| White, non-Hispanic | 0.019 ** [.008,.031] | 0.020 ** [.008,.031] | 0.74 ** [.30,1.19] |

| Intervention status | −0.004 [−.014,.005] | −0.004 [−.014,.005] | −0.13 [−.53,.27] |

| Constant | 0.033 [.007,.071] | 0.030 [.003,.067] | −2.497 [−3.73, −.95] |

| Overall R2 (Pseudo R2 in Model 3) | 0.231 | 0.236 | 0.143 |

Because BAC is typically scaled in small units (one-one thousandths), the coefficients associated with BAC are often large.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

The expectation that people who drink are more sexually available was not significant in bivariate analyses and, in the interest of a parsimonious model, excluded from the multivariate models. Expectations that people who drink are more fun was not significant when other characteristics are adjusted. Respondents’ histories of victimization—including verbal, physical, and weapons-related incidents—were initially included in the multivariate models. However, none of these items are significantly associated with the outcome when adjusted for demographic characteristics. Preliminary models examining the three measures of history of violence indicated a relationship between a history of having been violent while on drugs and evening drinking but did not indicate a relationship between evening drinking and a history of having beaten or used a weapon against another person. Thus, a history of violence while on drugs was the sole item indicating a respondent’s history of violence in the final models but was not a significant predictor of evening drinking in the multivariate analyses.

As expected, respondents’ drinking histories predicted evening drinking. Even controlling for southbound BACs measured at entry into the study, being a recent binge drinker predicted respondents’ northbound BAC measures (β=0.021; 95%CI=.011,.031), as did the self-report of being a frequent drinker (β=0.014; 95%CI=.004,.023). White non-Hispanic respondents drank more and were more likely to binge drink than counterparts of other race/ethnic groups.

Given the relationship between history of sexual assault and evening drinking, we examined the interaction between drinking and sexual assault histories. In model 2, the addition of the interaction produces only a marginal increase in the overall goodness of fit of the model. Nevertheless, this interaction suggested that the BACs of those with a history of both sexual assault and recent binge drinking experience tended to be even higher than those with problem behavior in only one area. We further examined this interaction in a maximum likelihood model of respondents measuring as evening binge drinkers (BAC≥0.08) when they returned northbound to California (model 3).

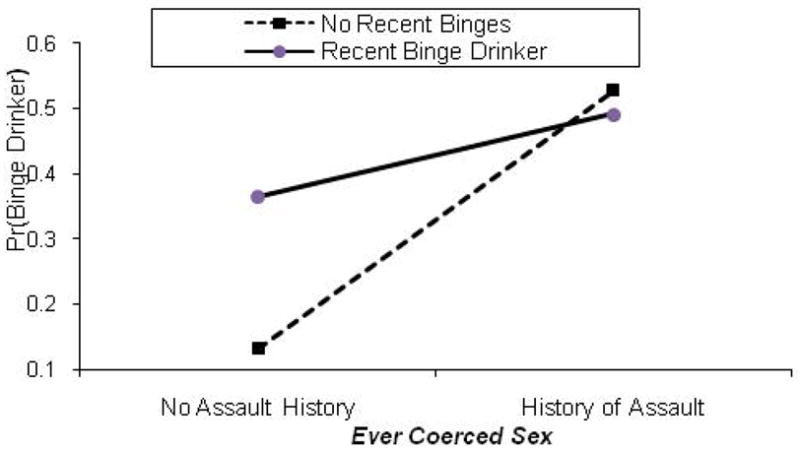

The interaction term indicated that the effect of sexual assault history on measuring as binge drinkers at the end of an evening in Tijuana was different for those respondents who self-reported to be recent binge drinkers than for those who were not recent binge drinkers. Stated differently, the effect of recent binge-drinking history, which we expected to predict evening drunkenness, differed according to each respondent’s sexual assault history. Examining the direct effects in model 3, the coefficient for sexual assault history (β=2.2; 95%CI=1.16,3.2) indicated, among respondents without a history of recent binge drinking, a greater likelihood for past sexual coercers to be evening binge drinkers than for respondents with no sexual assault history. Thus, among respondents with a recent history of binge drinking, the coefficient for sexual assault history (β=0.54; 95%CI=−.025,1.11, not shown in Table 3) indicated a slightly elevated likelihood (albeit not statistically significant at the α= 0.05 level) for past sexual coercers to be engaged in binge drinking than for respondents with no sexual assault history. The adjusted relationship between the two histories — recent binge drinking and sexual assault — and evening binge drinking is illustrated in Figure 1 (model 3). The predicted probability of evening binge drinking in Tijuana (BAC≥0.08) among recent binge drinking respondents was 0.36 for individuals with no sexual assault history and 0.49 for individuals with a history of sexual assault, an increase of 36%. Among respondents who had not recently been binge drinking, the predicted probability of evening binge drinking for individuals with a history of sexual assault (0.55) was 3.5 times the predicted probability of individuals with no sexual assault history (0.12).

Figure 1.

Adjusted Probability of Being an Evening Binge Drinker, Interaction of Sexual Assault, and Binge Drinking Histories

Note: Pr(Binge Drinker)=probability of being an evening binge drinker.

Discussion

Knowing that sexual assault histories are associated with drinking behavior and with subsequent incidences of sexual assault, the purpose of this study was to examine individual sexual assault histories as predictors of evening drinking. This study examined how much alcohol young men (generally of college-age) consumed during an evening in Tijuana and established the association between history of sexual assault and evening drinking behavior. We found that sexual assault histories were associated with increased drinking and greater likelihood of binge drinking, even when we control for individuals’ drinking and violence histories as well as their attitudes about the drinking of others. Although we could not estimate a rate of sexual assault during the evening in Tijuana with these data, establishing the relationship between respondents’ histories of drinking, violence, and sexual assault and their evening drinking constitutes a further step in our understanding of a risky environment that may be associated with further instances of sexual assault.

In situations where binge drinking is prevalent, such as Tijuana and other timeout locales, the opportunity for sexual assault increases. A study of the impact of bar density on local norms of aggression and alcohol-related aggression suggests that alcohol-related aggression may be tolerated to a degree, even when aggression alone is less normative (Treno, Gruenewald, Remer, Johnson, & LaScala, 2008). Episodes of heavy drinking were also associated with higher levels of self-reported aggression, even among individuals who drink a similar amount on average over time (Treno et al., 2008), suggesting that environments that encourage binge drinking increase the risk of violent incidents.

Drinking on site may not be the only risk factor warranting further investigation. The tendency towards beginning heavy drinking before arriving at one’s nightlife destination has been documented (Hughes, Anderson, Morleo, & Bellis, 2008). In our sample of males crossing the border, those who started the evening after consuming even small amounts of alcohol were more likely to drink heavily while in Tijuana. Given the association between sexual assault histories and evening binge drinking, further research is needed to explore whether the identification of individuals who begin heavy drinking earlier in the evening may help identify individuals at risk of sexual assault during the evening.

Overall, prevention efforts need to target different audiences to reduce victimization among college-age individuals, particularly in alcohol-rich environments. Greater efforts to target male behavior are at least as important as providing training for female safety but are still underdeveloped (Hong, 2000). Although preventive efforts may have a limited effect on men who exhibit more hostility toward women and more potential for coercive interactions, the compounding effect of alcohol on male behavior argues for continued preventive work even among men not known to exhibit coercive behavior (Stephens & George, 2004, 2009). From another perspective, fostering bystanders confidence (among both males and females) to intervene in situations leading to intimate violence represents a growing effort to target different players to reduce the incidence of sexual assault (Banyard, 2008; Barone, Wolgemuth, & Linder, 2007).

Our study is both enriched and limited by the border locale from which we drew our sample, and it would be appropriate to seek to replicate these findings in a geographically representative sample of college-age males. While educational attainment and status is relevant to young adults’ drinking behavior (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009; O’Malley & Johnston, 2002), we were not able to include data on our respondents’ educational characteristics in our analysis. Further work in the general population should carefully collect this information. Our sample was drawn for a female victimization intervention, with the selection of peer groups conditioned on at least one group member being female. The intervention was targeted to female study participants but did include a component encouraging moderation of alcohol use, which may contribute to a bias in the alcohol outcomes used in this study. Further, although the border environment provided an ideal location to conduct this type of portal survey (Voas et al., 2006; ) in a population of college-age Americans seeking an alcohol-rich timeout experience, the results of this study may not be applicable to college campuses or other American bar environments. Studies of drinking behavior at dance parties (Furr-Holden, Voas, Kelley-Baker, & Miller, 2006) and in American college bars (Clapp et al., 2007) illustrate the application of portal studies in different environments, and further research conducted in randomly selected bars in a college town is being pursued. Still, there is an inherent risk to response validity in relying on self-response from individuals who have consumed varying amounts of alcohol prior to completing the interview, and further research to validate responses would be constructive. Notably, respondents may be concerned about reporting their sexual assault histories, but collecting reports of sexual assault through self-administered (paper-and-pencil or Web) instruments, particularly when drugs or alcohol may have been involved, is expected to alleviate respondents’ anxieties associated with reporting antisocial behaviors (Ouimette, Shaw, Drozd, & Leader, 2000). Our study instrument used items from the original Sexual Experiences Survey; the revised SES (Koss et al., 2007) published once our project was underway addresses various criticisms of the original items including alcohol-related assaults and should be used in further study of this topic.

In sum, there exists a strong link between sexual assault histories and college-age males’ alcohol consumption. Although the link between BAC and contemporaneous sexual assaults on a given evening was not made through this study, intervention efforts should particularly focus on men who start drinking early in the evening, at least to reduce their risk of alcohol-related problems. Establishing the relationship between increased alcohol consumption and coincident sexual assault by individuals with a sexual assault history will require a larger sample without peer-group restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ acknowledge the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism (NIH/NIAAA R01 AA015118-01).

References

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl 14):118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO. The effects of past sexual assault perpetration and alcohol consumption on men’s reactions to women’s mixed signals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(2):129–155. doi: 10.1521/jscp.24.2.129.62273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton AM, McAuslan P. Alcohol and sexual assault. Alcohol Research and Health. 2001;25(1):43–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL. Measurement and correlates of prosocial bystander behavior: the case of interpersonal violence. Violence and Victims. 2008;23(1):83–97. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone RP, Wolgemuth JR, Linder C. Preventing sexual assault through engaging college men. Journal of College Student Development. 2007;48(5):585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Burt MR. Cultural myths and supports for rape.” J Pers Soc Psychol 38(2): 217–30. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38(2):217–230. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Holmes MR, Reed MB, Shillington AM, Freisthler B, Lange JE. Measuring college students’ alcohol consumption in natural drinking environments: Field methodologies for bars and parties. Evaluation Review. 2007;31(5):469–489. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07303582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermen KH, Cooper ML. Sex-related alcohol expectancies among adolescents: I. Scale development. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994a;8(3):152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dermen KH, Cooper ML. Sex-related alcohol expectancies among adolescents: II. Prediction of drinking in social and sexual situation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994b;8(3):161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Dermen KH, Cooper ML, Agocha VB. Sex-related alcohol expectancies and moderators of the relationship between alcohol use and risky sex in adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(1):71–77. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris C, Viken RJ. Heterosocial perceptual organization: application of the choice model to sexual coercion. Psychological Science. 2006;17(10):869–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG. The Sexual Victimization of College Women (182369) Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. Dec, [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden CDM, Voas RB, Kelley-Baker T, Miller B. Drug and alcohol-impaired driving among electronic music dance event attendees. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85(1):83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009 July;(16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L. Toward a transformed approach to prevention: Breaking the link between masculinity and violence. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(6):269–279. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Griffin MA, Boekeloo BO. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of alcohol-related sexual assault among university students. Adolescence. 2008;43(172):733–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Anderson A, Morleo M, Bellis MA. Alcohol, nightlife and violence: the relative contributions of drinking before and during nights out to negative health and criminal justice outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103(1):78–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques-Tiura AJ, Abbey A, Parkhill MR, Zawacki T. Why do some men misperceive women’s sexual intentions more frequently than others do? An application of the Confluence model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33(11):1467–1480. doi: 10.1177/0146167207306281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TJ, Stahl C. Sexual experiences associated with participation in drinking games. Journal of General Psychology. 2004;131(3):304–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Baker T, Mumford EA, Vishnuvajjala R, Voas RB, Romano E. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. The Free Library; 2008. Dec 1, A night in Tijuana: Female victimization in a high-risk environment. Retrieved January 27, 2009 from http://www.thefreelibrary.com/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, et al. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual experiences survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:455–457. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listiak A. Legitimate deviance and social class: Bar behavior during Grey Cup Week. Sociological Focus. 1974;7(3):13–44. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. What Colleges Need to Know Now An Update on College Drinking Research (NIH Publication No. 07-5010) Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl 14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette PC, Shaw J, Drozd JF, Leader J. Consistency of reports of rape behaviors among nonincarcerated men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2000;1(2):133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill MR, Abbey A, Jacques-Tiura AJ. How do sexual assault characteristics vary as a function of perpetrators’ level of intoxication? Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(3):331–333. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Miller BA. Bar victimization of women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:509–525. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens KA, George WH. Effects of anti-rape video content on sexually coercive and noncoersive college men’s attitudes and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34:402–416. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens KA, George WH. Rape prevention with college men: Evaluating risk Status.” J Interpers Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(6):996–1013. doi: 10.1177/0886260508319366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Treno AJ, Gruenewald PJ, Remer LG, Johnson F, LaScala EA. Examining multi-level relationships between bars, hostility and aggression: Social selection and social influence. Addiction. 2008;103(1):66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Furr-Holden CDM, Lauer E, Bright C, Johnson MB, Miller B. Portal surveys of timeout drinking locations: A tool for studying binge drinking and AOD use. Evaluation Review. 2006;30(1):44–65. doi: 10.1177/0193841X05277285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC. Sexuality and women’s drinking: Findings from a U.S. national study. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1991;15(2):147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki T, Abbey A, Buck PO, McAuslan P, Clinton-Sherrod AM. Perpetrators of alcohol-involved sexual assaults: How do they differ from other sexual assault perpetrators and nonperpetrators? Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(4):366–380. doi: 10.1002/ab.10076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]