Abstract

Late-onset sepsis in premature infants is a major cause of morbidity, mortality, and increased medical costs. Risk factors include low birth weight, low gestational age, previous antimicrobial exposure, poor hand hygiene, and central venous catheters. Methods studied to prevent late-onset sepsis include early feedings, immune globulin administration, prophylactic antimicrobial administration, and improved hand hygiene. In this review, we will outline the risk factors for development of late-onset sepsis and evidence supporting methods for prevention of late-onset sepsis in premature infants.

1. INTRODUCTION

Late-onset sepsis (LOS) is a common complication of prolonged admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) following preterm birth [1]. Neonatal sepsis is categorized as either early-onset (EOS) or LOS. EOS, often due to group B Streptococci or Escherichia coli, occurs in the first 3 days of life and is associated with prolonged rupture of membranes, maternal colonization with group B Streptococci, and prematurity [2–3] LOS occurs after the third day of life and, among premature infants, is most often caused by Gram-positive organisms [1,4].

2. ORGANISMS

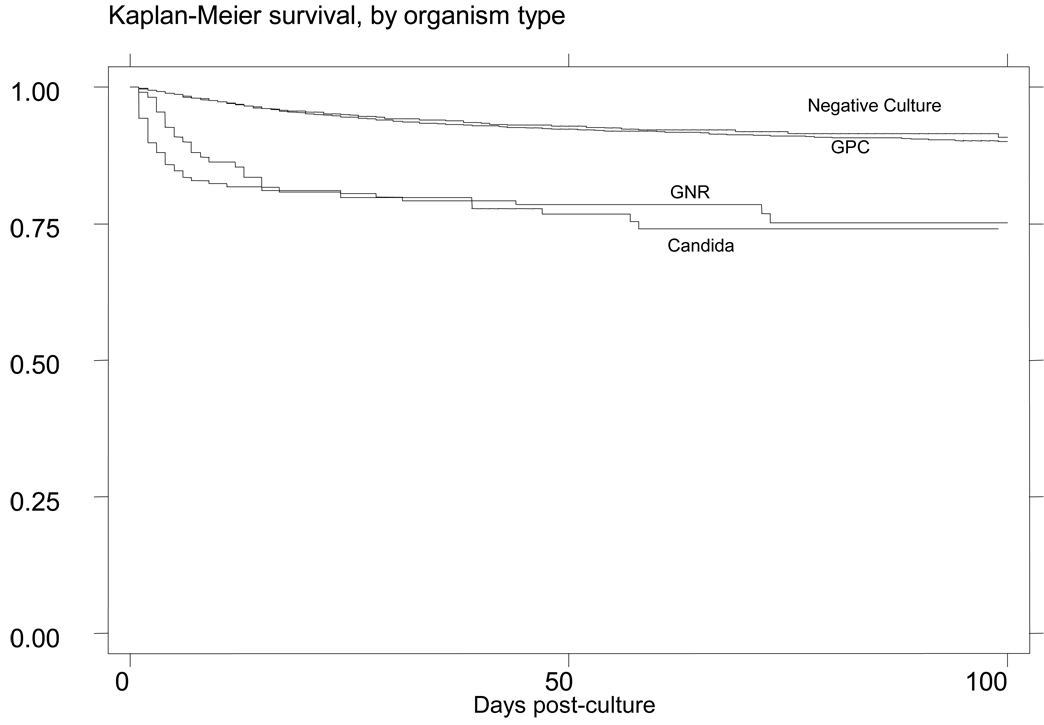

The causative organism in LOS is an important predictor of overall outcome. Gram-positive organisms account for 45–77% of infections [1–2,5]. Of the Gram-positive organisms, coagulase-negative Staphylococci are the most prevalent [1–2,4,6–7]. In a large cohort of infants who had blood cultures drawn, mortality was similar between infants with a negative first blood culture 8% (390/4648) and those infants with Gram-positive infections 6% (10 /169), HR=0.74; 95% CI 0.4 – 1.39. (Figure 1) [6].

Figure 1.

Survival after a blood culture [6]

Although less prevalent, Gram-negative organisms are associated with greater mortality (19% – 36%) [1,6]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is associated with the highest mortality among premature infants, 45% – 74% [1–2,8]. A study of 49 cases of fulminant cases of LOS (deaths occurring within 48 hours of the first positive culture) in infants admitted to the NICU reported that 69% of the fulminant cases were a result of a Gram-negative organism, the most common being Pseudomonas sp. (42%) [4] A report of 6956 infants found that 71% (66/93) of deaths attributed to Gram-negative sepsis occurred within three days of the last positive blood culture [1]. Candida infections account for 6% – 18% of cases of LOS among all infants admitted to the NICU[2,4,9], and mortality ranges from 22% – 32% [3,6,9].

3. Morbidities

Premature infants enrolled in the NICHD’s Neonatal Research Network Generic Database undergo developmental testing at 18–22 months corrected age. Neurodevelopmental impairment at this visit is defined as a score of < 70 on Mental or Psychomotor Developmental Index on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II, cerebral palsy, blindness, or deafness. Using multivariable analysis, investigators demonstrated that extremely low birth weight (ELBW, < 1000 g birth weight) infants who developed sepsis were more likely to have neurodevelopmental impairment at 18–22 months corrected age, odds ratio (OR) for neurodevelopmental impairment 1.5 [95% confidence interval; 1.2, 1.7] compared to those infants without an episode of sepsis. [10]. A study of ELBW infants found that infants with candidiasis were more likely than to have a Bayley Scales of Infant Development Mental Developmental Index (48% vs. 30%; p<0.001) or Psychomotor Developmental Index (32% vs. 20%; p<0.001) score < 70 compared to uninfected infants or infants infected with bacterial organisms [11].

LOS also increases medical costs. Adjusted for mortality, Candida infections in the NICU are associated with a $28,000 increase in medical costs (p<0.001) among affected infants [12]. Infants with LOS also have longer hospital stays than infants without LOS, (79 days vs. 60 days, <0.001) [1]. These analyses do not account for the long term care costs associated with caring for a child with neurodevelopmental delay.

4. RISKS

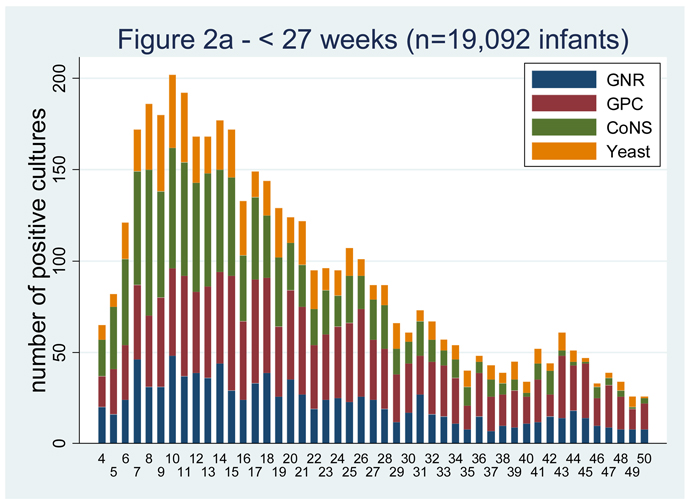

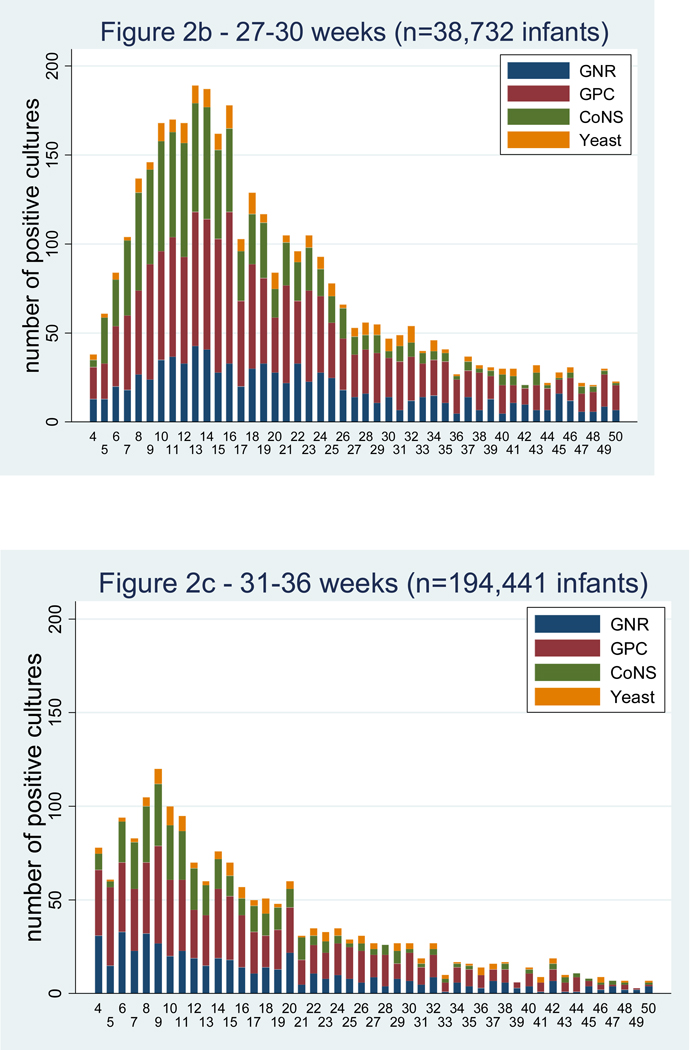

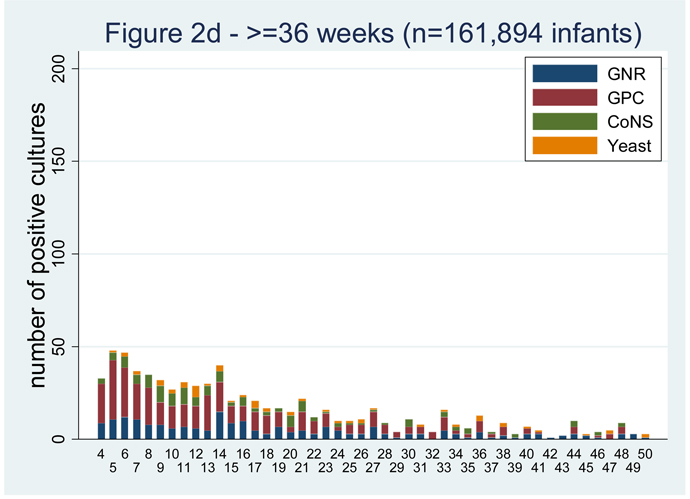

4.1. Birth weight and gestational age

LOS is more common among the most premature infants.[1–3,5,10,13]. Among infants < 750 g birth weight, the cumulative incidence of LOS is 43% [1]. In a cohort of infants admitted to 250 NICUs in the US, there were 374 infections for every 1000 admissions for infants < 750 g birth weight and only 7 infections per 1000 admissions in infants >2500 g birth weight (Table 1). The majority of the infections occur in the first 40 days of life (Figure 2) [14]. Invasive candidiasis occurs in 11.4% of infants weighing 400–750 g at birth compared to only 3.4% for those weighing 751–1000 g (P<0.0001) [11].

Table 1.

Bloodstream infections per 1000 admission

| < 750 g | 750–999 g | 1000–1499 g | 1500–2499 g | ≥ 2500 g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | 231.3 | 143.9 | 52.2 | 7.1 | 4.5 | |

| Coagulase Negative | ||||||

| Staphylococci | 97.1 | 54.9 | 18.3 | 2.1 | 1.1 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 44.1 | 32.3 | 12.6 | 1.7 | 0.9 | |

| Enterococcus sp | 27.5 | 16.0 | 4.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 | |

| Group B Streptococcus | 7.3 | 5.6 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Listeria | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Gram-negative | 86.0 | 54.9 | 20.5 | 3.5 | 2.1 | |

| Escherichia coli | 15.5 | 10.7 | 5.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 | |

| Klebsiella sp | 20.9 | 13.0 | 5.6 | 0.9 | 0.5 | |

| Enterobacter sp | 15.3 | 10.8 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |

| Serratia sp | 8.6 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Pseudomonas sp | 9.2 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Citrobacter sp | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | |

| Candida sp. | 53.1 | 21.2 | 5.2 | 1.0 | 0.5 | |

| Total | 373.9 | 222.5 | 78.7 | 11.7 | 7.2 | |

Figure 2.

Positive blood cultures over the first 50 days of life by gestational age group [14].

4.2. Medical center

Individual medical centers play a role in the risk of LOS in the NICU [15]. A study of LOS in VLBW infants in the NICHD Neonatal Research Network found that LOS infection rates varied from 11% to 32% (p < 0.001) [1]. Among the same centers the incidence of candidiasis ranged from 2% to 20% for ELBW infants, with an average incidence of 8% [15].

4.3. Central lines

Central venous catheters (CVCs), used frequently in the NICU to administer parenteral nutrition, antimicrobials, and other medicines, are a risk factor for the development of LOS [2,5,9]. A study of 180 infants admitted to the NICU found that infants with Candida infections had a CVC for a mean of 22 days compared to 8 days for those without an infection (P<0.0001) [9]. Bloodstream infections resulting from CVCs may occur from either intraluminal or extraluminal contamination. Intraluminal contamination occurs from contaminated intravenous fluids or contaminated catheter hub. Extraluminal infections occur when organisms colonizing the skin travel along the catheter track. Extraluminal infections can be identified when the blood culture organism is the same the organism isolated from a culture of the catheter tip. Thirty-two bloodstream infections were reported from a cohort of 82 infants, 15 of which were identified as being definite or probable catheter related infections [16]. Intraluminal contamination was identified as the cause in 67% (10/15).

A concern for clinicians caring for preterm infants is the length of time that a CVC can be kept safely in place before replacing the CVC with a new one. In an analysis of 135 cases of catheter related infections in one NICU over a 27 month period, increased dwell time was not associated with an increased risk of infection [17]. There were 8.4 bloodstream infections per 1000 catheter days during the 1st week that the catheter was in place, 9.6 per 1000 days during the 2nd week, and 4.5 per 1000 days after 5 weeks of placement. This observed decline in risk of infection with longer dwell time may have been due to the infants’ maturing immune system, improved nutrition, and decreased need of other invasive interventions during the period of time that the catheter was in place.

Total parental nutrition, and mechanical ventilation [1–2,5] have also been shown to increase an infant’s risk of infection. Additional risk factors for Candida infections include a previous bloodstream infection, OR=8.0 [2.8 – 23.3], [9] and previous exposure to 3rd generation cephalosporins, OR=1.8 [1.3 – 2.4][11].

5. Preventions

5.1. Handwashing

Proper hand hygiene is the most important methods of preventing the spread of nosocomial infections [18]. Hand hygiene educational programs decrease infection rates in the NICU [19–21], as has the implementation of a designated infection control healthcare worker [22].

Although improving handwashing compliance is important, sustaining compliance over long periods of time is difficult. A study comparing several previously published hand hygiene programs in adult populations found the most successful and sustainable approach was one based on continued staff involvement, including senior staff [23]. With this approach the investigators showed a 48% improvement in hand hygiene practices (p < 0.001) over the 2 year study period.

Evidence supporting the use of one hand hygiene product over the other is unclear. There was no difference in infection rates between the use of a 61% ethanol and emollient containing hand rub (12.1 infections/1000 patient days) and an antiseptic soap containing 2% chlorhexidine (9.5 infections/1000 patient days) in a NICU (p=0.88) [24]. A study done in a NICU showed a decrease in infection rate from 13.5 infections per 1000 patients to 4.8 per 1000 patients after changing from a hand washing system to an alcohol hand rub and glove protocol [25]. Although this decrease was not statistically significant, there was a significant decrease in the incidence of MRSA infections (14% to 3%, p < 0.05) and cases of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (25% to 7%, p < 0.0001).

Given the small efficacy differences between products, hand hygiene efforts should focus primarily on improving compliance.

5.2. Immune globulin

Premature infants have lower levels of transplacentally acquired IgG than their full term counterparts [26]. Because of this, investigators have evaluated the use of immune globulin for the prevention and treatment of infection. Immune globulin was effective in reducing nosocomial infections among 588 infants 500 – 1750 g birth weight; 24% (70/287) in the immune globulin group vs. 35% (104/297) in the placebo group, relative risk = 0.7 [0.5, 0.9][27]. However, a larger study of 2416 infants 501 – 1500 g birth weight given either immune globulin or placebo every 14 days until a weight of 1800 g found no significant difference in infection rates, immune globulin 17% (208/1204) vs. placebo, 19% (231/1212), p = 0.25 [28].

Staphylococcus aureus accounts for 8% – 12% [1,4–5] and coagulase negative Staphyloccoci account for 35%–48% [1,4] of LOS in the NICU. INH-A21 is a donor obtained immune globulin with high antibody titers to Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. In a randomized placebo controlled study of INH-A21 in infants with birth weights 500 – 1250 g, there was a non-statistically significant reduction in Staphylococcus.aureus infections in the highest dose of 750 mg/kg INH-A21 group versus placebo, 7% (11/158) vs. 3% (4/157), p = 0.14 [29]. A study of 2017 VLBW infants using INH-A21 found no difference in Staphylococcus aureus infection rates in the group receiving INH-A21 versus placebo, 6% (60/994) and 5% (50/989), p = 0.34 [30].

Altastaph [Staphylococcus aureus Immune Globulin (Human)] (Nabi biopharmaceuticals), is an intravenous immune globulin to type 5 and 8 capsular polysaccharide, produced by 85% of Staphylococcus aureus isolates [31]. A randomized study of Altastaph used as prophylaxis against infection in 206 VLBW infants found that it was safe to use in this population but no difference in efficacy was observed, 15% (16/104) of the Altastaph group and 15% (16/102) in the placebo group became infected with 3 infections in each group caused by Staphylococcus aureus. [31].

Pagibaximab is a human chimeric monoclonal that has anti-staphylococal characteristics and, therefore, may have a role in preventing staphylococcal infections [32]. In a study of 88 VLBW infants randomized to 1 of 3 groups; 60mg/kg or 90 mg/kg of pagibaximab or placebo, the 90mg/kg group had fewer staphylococcal infections compared to the 60 mg/kg and placebo group; 0%, 20%, and 13%, respectively, p < 0.11 [32].

5.3. Feedings

Although there are concerns that early feeds in critically ill preterm infants may increase the risk of NEC, establishing early feedings may be protective against infection. In a retrospective study of 385 VLBW infants, infants that did not acquire a nosocomial infection were started on enteral feeds earlier than those that had a nosocomial infection, 2.8 days vs. 4.8 days, p=0.0001 [33]. There was no difference in NEC among infants fed earlier compared to infants fed at a later point. A study of 405 ELBW infants found that infants who established full feeds with human breast milk (HBM) during the first, second, third, and fourth weeks of life had a 9%, 11%, 37%, and 40% chance respectively of developing sepsis [7].

In addition to timing of feedings, the type of feed given to an infant plays an important a role in infection prevention [33]. A study of 212 VLBW infants fed with either HBM or formula found that infants receiving any amount of HBM had an overall infection rate of 29% versus 47% in those exclusively formula fed, p = 0.01 [34]. HBM is also protective against development of NEC. A study of 202 VLBW infants, compared infants that received > 50% HBM in the first 14 days of life vs. those that received < 50% HBM and found a six fold decrease in the risk of NEC in the group getting >50% HBM [35].

Lactoferrin, a glycoprotein present in HBM has antimicrobial properties [36–37]. Investigators randomized 302 VLBW infants to 1 of 3 supplement groups; lactoferrin, lactoferrin and Lactobacillus RhamnosusGG (a probiotic), or placebo [36]. The percentage of each group that developed LOS was 9.3%, 5.9%, and 26.1% respectively, with both the supplement groups having a significantly lower incidence of LOS than placebo (p=0.008 and p<0.001).

5.4. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis

Gram-positive organisms are the most common causes of LOS and CVCs are a major risk factor for development of infection. Vancomycin catheter locks have demonstrated efficacy in several studies of pediatric oncology patients [38–39]. A study of 85 VLBW infants randomized subjects to CVCs locked with either vancomycin or normal saline found a significantly lower incidence of infection in the vancomycin group than in the placebo group, 17% vs. 42%, p = 0.01 [40]. No vancomycin-resistant organisms were cultured during the study period, and those infants with vancomycin locks who had not received intravenous vancomycin did not have detectable systemic levels of the vancomycin. Before widespread adoption of vancomycin locks, larger studies and longer term surveillance for resistance are needed.

Topical and systemic antifungal prophylaxis has been evaluated for prevention of Candida infections in preterm infants. Ozturk et al. preformed a randomized study of oral Nystatin vs. placebo [41]. The 3991 infants were divided into 3 groups; those that received Nystatin, those that received Nystatin if they were colonized with Candida, and those who received no treatment. This study reported a significantly reduced rate of invasive Candida disease with infection rates of 1.8% (36/1996), 5.6% (27/479), and 14.2% (215/1516), respectively, p = 0.004.

A randomized placebo controlled study of 100 ELBW infants given fluconazole prophylaxis or placebo in the first 6 weeks of life demonstrated a significant reduction in invasive fungal disease [42]. Invasive fungal disease was found in 20% of the placebo group and in none of the infants receiving the prophylaxis, p = 0.008. However, the rate of candidiasis in the control group was 3 times the average candidiasis rate of the centers in the NICHD’s Neonatal Research Network [15]. A second study of 81 ELBW infants compared daily fluconazole dosing to twice weekly dosing found similar infection rates in both groups, 5% with daily dosing vs. 3% with twice weekly dosing, p = 0.68 [43]. Manzoni et al. performed a multicenter study evaluating prophylactic fluconazole in 322 VLBW infants [44]. There were 3 study groups; those receiving 6 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg, or placebo. The rates of invasive fungal disease were 2.7%, 3.8%, and 13.2%, respectively (p = 0.005 for the 6 mg group and p = 0.02 for the 3 mg group). There was no difference in mortality between the groups. Again, these results are difficult to interpret as the average rate of invasive candidiasis reported in VLBW infants throughout much of the world is 3% or less [45].

6. Safety of Interventions

Before implementation of widespread interventions to prevent LOS, clinicians must evaluate infection rates in their own nursery. For example, in a NICU with a cumulative incidence of invasive candidiasis of 1.2%, 100 infants would need to be treated with fluconazole prophylaxis to prevent 1 infection (Table 2). However, for NICUs where the cumulative incidence is 17.9%, only 7 infants would need to be treated to prevent one infection.

Table 2.

The number needed to treat with prophylaxis for candidiasis and variations in different centers given an 80% reduction in candidiasis with prophylaxis and 33% attributable mortality rate of candidiasis. [42]

| No prophylaxis | Fluconazole prophylaxis |

Risk Difference | NNT - Candidiasis | NNT Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | >250 | >750 |

| 1.2% | 0.2% | 1.0% | 100 | 300 |

| 2.1% | 0.4% | 1.7% | 59 | 177 |

| 4.4% | 0.9% | 3.5% | 29 | 87 |

| 6.7% | 1.3% | 5.4% | 19 | 57 |

| 10.7% | 2.1% | 8.6% | 12 | 36 |

| 17.9% | 3.6% | 14.3% | 7 | 21 |

| 26.8% | 5.4% | 21.4% | 5 | 15 |

Prophylaxis studies frequently have high control (or placebo group) infection rates; referred to as the “prophylaxis paradox” [46]. In a center with a high baseline rate of infection, demonstrating efficacy of a prophylactic intervention is less difficult than in centers with lower rates of infection. A center with a baseline invasive candidiasis rate of 25% would only need 340 infants to have 80% power to detect a 50% decrease in infections with alpha=0.05. A center with an invasive candidiasis rate of 7% would need 1400 subjects.

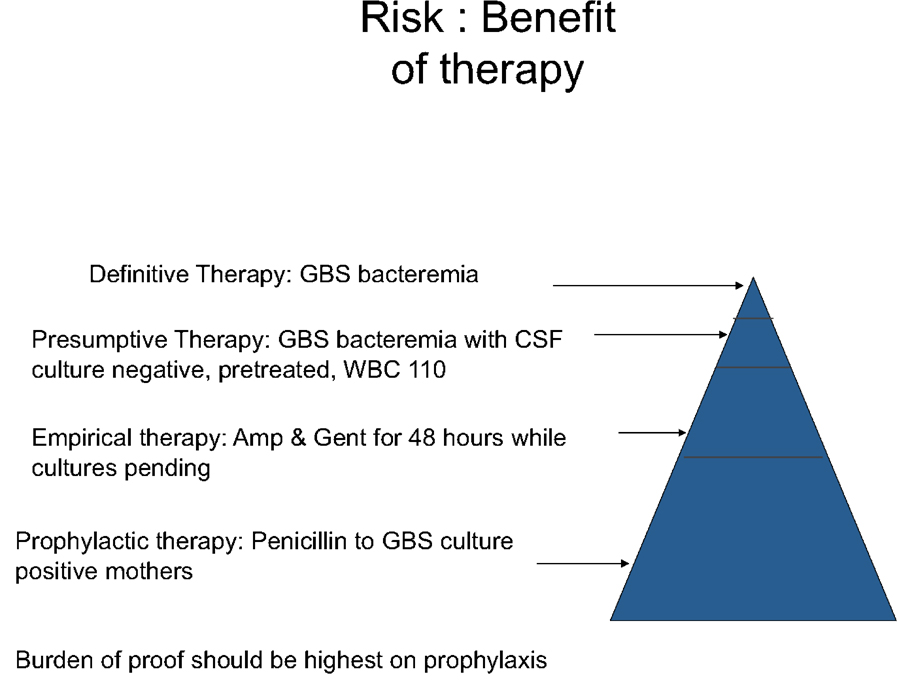

The bar for demonstrating efficacy should be higher for prophylactic interventions compared to therapies used empirically or for treatment as often the majority of exposed subjects will never ultimately develop the disease (Figure 3). A therapeutic agent used for treating a disease may have serious side effects and still prove to have a favorable risk to benefit ratio. For example, chemotherapeutic drugs are one of the mainstays of cancer treatment even though many have serious side effects. The adverse effects are acceptable here because the alternate of leaving a cancer untreated is usually unacceptable. The approach toward a prophylactic treatment is much different. This type of treatment is given to many without disease to prevent just a few from acquiring that disease. Therefore, it is imperative that the prophylactic intervention be proven very safe prior to administration. There have been instances in neonatology where this has not been done and the result was injury to the infants receiving the treatment. One such example was the use penicillin/sulfisoxazole as prophylaxis against infection in low birth weight infants in the early 1950’s. It was not until 18 months after initiation of this practice that a trial to evaluate the safety of this agent was conducted [47]. The study compared the use of this drug regimen with the use of oxytetracycline in 193 infants and discovered that the group receiving the penicillin/sulfisoxazole had a significantly higher incidence of kernicterus than the oxytetracycline group (36% vs 6% of deaths in the first 120 hours and 43% vs. 5% of deaths in the first 28 days). However, most serious adverse events are rare and difficult to detect in the limited sample size of virtually all clinical trials in infants. For example, in order to have 80% power to detect a doubling of the incidence of adverse events with the use of a new therapeutic agent compared to a control adverse event incidence of 1%, investigators would have to enroll 5000 subjects.

Figure 3.

Burden of proof required to institute therapy.

7. Conclusion

LOS is common in premature infants and is associated with significant mortality, neurodevelopmental impairment among survivors, and increased health care costs. Although several interventions have proven effective under specific conditions, aside from improved hand hygiene, larger studies performed at sites with baseline infection rates representative of most NICUs and analysis of long term outcome data (resistance, neurodevelopmental outcomes) are needed before widespread adoption of these measures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Late-Onset Sepsis in Very Low Birth Weight Neonates: The Experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2002;110:285–291. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang J, Chiu N, Huang F, Kao H, Hsu C, Hung H, et al. Neonatal sepsis in the neonatal intensive care unit: characteristics of early versus late onset. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Changes in pathogens causing early-onset sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:240–247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karlowicz MG, Buescher ES, Surka AE. Fulminant late-onset sepsis in a neonatal intensive care unit, 1988–1997, and the impact of avoiding empiric vancomycin therapy. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1387–1390. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlman SE, Saiman L, Larson EL. Risk factors for late-onset healthcare-associated bloodstream infections in patients in neonatal intensive care units. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin DK, DeLong E, Cotten CM, Garges HP, Steinbach WJ, Clark RH. Mortality following blood culture in premature infants: Increased with gram-negative bacteremia and candidemia, but not gram-positive bacteremia. J Perinatol. 24:175–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ronnestad A, Abrahamsen TG, Medbo S, Reigstad H, Lossius K, Kaaresen PI, et al. Late-onset septicemia in a Norwegian national cohort of extremely premature infants receiving very early full human milk feeding. Pediatrics. 115:e269–e276. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng Y, Chiu Y, Wang J, Lin H, Lin H, Su B, Chiu H. Nosocomial bloodstream infecrion in a neonatal intensive care unit of a medical center: a three-year review. J Microbiol immunol Infect. 35:168–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feja KN, Wu F, Roberts K, Loughrey M, Nesin M, Larson E, et al. Risk Factors for Candidemia in Critically Ill Infants: A Matched Case-Control Study. J Pediatr. 2005;147:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, Higgins RD. Neurodevelopmental and Growth Impairment Among Extremely Low-Birth-Weight Infants With Neonatal Infection. JAMA. 2004;292:2357–2365. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benjamin DK, Stoll BJ, Fanaroff AA, McDonald SA, Oh W, Higgins RD, et al. Neonatal candidiasis among extremely low birth weight infants: risk factors, mortality rates, and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18–22 months. Pediatrics. 2006;117:84–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PB, Morgan J, Benjamin DK, Fridkin SK, Sanza LT, Harrison LH, et al. Excess costs of hospital care associated with neonatal candidemia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:197–200. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000253973.89097.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su B, Hsieh H, Chiu H, Lin H, Lin H. Nosocomial infection in a neonatal intensive care unit: A prospective study in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith PB, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Benjamin DK, Cotten CM, Clark RH, Benjamin DK., Jr . Late Onset Sepsis in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Honolulu, HI: Society for Pediatric Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotten CM, McDonald S, Stoll B, Goldberg RN, Poole K, Benjamin DK, et al. The association of third-generation cephalosporin use and invasive candidiasis in extremely low birth-weight infants. Pediatrics. 2006;118:717–722. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garland JS, Alex CP, Sevallius JM, Murphy DM, Good MJ, Volberding AM, et al. Cohort study of the pathogenesis and molecular epidemiology of catheter-related bloodstream infection in neonates with peripherally inserted central venous catheters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:243–249. doi: 10.1086/526439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith PB, Benjamin DK, Cotten CM, Schultz E, Guo R, Nowell L, et al. Is an increased dwell time of a peripherally inserted catheter associated with an increased risk of bloodstream infection in infants? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:749–753. doi: 10.1086/589905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyce JM, Pittet D Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee; HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings. Recommendations of the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee and the HICPAS/SHEA/APIC/IDSA hand hygiene task force. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Infectious Disease Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-16):1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capretti MG, Sandri F, Tridapalli E, Galletti S, Petracci E, Faldella G. Impact of a standardized hand hygiene program on the incidence of nosocomial infection in very low birth weight infants. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam BCC, Lee J, Lau YL. Hand hygiene practices in a neonatal intensive care unit: a multimodal intervention and impact on nosocomial infection. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e565–e571. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pessoa-Silva CL, Hugonnet S, Pfister R, Touveneau S, Dharan S, Posfay-Barbe K, Pittet D. Reduction of health care-associated infection risk in neonates by successful hand hygiene promotion. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e382–e390. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UK Neonatal Staffing Study Group. Relationship between probable nosocomial bacteraemia and organizational and structural factors in UK neonatal intensive care units. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:264–269. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.012690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitby M, McLaws M, Slater K, Tong E, Johnson B. Three successful interventions in health care workers that improve compliance with hand hygiene: is sustained replication possible. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson EL, Cimiotti J, Haas J, Parides M, Nesin M, Della-Latta P, Saiman L. Effect of antiseptic handwashing vs alcohol sanitizer on health care-associated infections in neonatal intensive care units. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:377–383. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng PC, Wong HL, Lyon DJ, So KW, Liu F, Lam RKY, et al. Combined use of alcohol hand rub and gloves reduces the incidence of late onset infection in very low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F336–F340. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.031104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballow M, Cates KL, Rowe JC, Goetz C, Desbonnet C. Development of the immune system in very low birth weight (less than 1500 g) premature infants: concentrations of plasma imunoglobulins and patterns of infections. Pediatr Res. 1986;20:899–904. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198609000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker CJ, Melish ME, Hall RT, Castro DT, Vasan U, Givner LB. Intravenous immune globulin for the prevention of nosocomial infection in low-birth-weight neonates. The Multicenter Group for the Study of Immune Globulin in Neonates. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:213–219. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207233270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fanaroff AA, Korones SB, Wright LL, Wright EC, Poland RL, Bauer CB, et al. A controlled trial of intravenous immune globulin to reduce nosocomial infections in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J MED. 1994;330:1107–1113. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404213301602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloom B, Schelonka R, Kueser T, Walker W, Jung E, Kaufman D, et al. Multicenter study to assess safety and efficacy of INH-A21, a donor-selected human staphylococcal immunoglobulin, for prevention of nosocomial infections in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:858–866. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000180504.66437.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeJonge M, Burchfield D, Bloom B, Duenas M, Walker W, Polak M, et al. Clinical trial of safety and efficacy of INH-A21 for the prevention of nosocomial staphylococcal bloodstream infection in premature infants. J Pediatr. 2007;151:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benjamin DK, Schelonka R, White R, Holley HP, Bifano E, Cummings J, et al. A blinded, randomized, multicenter study of an intravenous Staphyloccus aureus immune globulin. J Perinatol. 2006;26:290–295. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thackray H, Lassiter W, Walsh W, Brozanski B, Steinhorn R, Dhanireddy R, Weisman LE the MAB N003 Study Group. Phase II randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, safety, pharmacokinetics (PK), and clinical activity study in very low birth weight (VLBW) neonates of pagibaximab, a monoclonal antibody for the prevention of Staphylococcal infection. San Francisco, CA: Poster Presentation, Society for Pediatric Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flidel-Rimon O, Friedman S, Lev E, Juster-Reicher A, Amitay M, Shinwell ES. Early enteral feeding and nosocomial sepsis in very low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F289–F292. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.021923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hylander MA, Strobino DM, Dhanireddy R. Human milk feedings and infection among very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:e38–e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sisk PM, Lovelady CA, Dillard RG, Gruber KJ, O’Shea TM. Early human milk feeding is associated with a lower risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol. 2007;27:428–433. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manzoni P, Mosca F, Messner H, Magaldi R, Cattani S, Stronati M, Farina D. A multicenter randomized trial on prophylactic bovine lactoferrin in preterm neonates: preliminary data. Honolulu, HI: Society for Pediatric Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnold RR, Brewer M, Gauthier JJ. Bactericidal activity of human lactoferrin: sensitivity of a variety of microorganisms. Infect Immun. 1980;28:893–898. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.893-898.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barriga FJ, Varas M, Potin M, Sapunar F, Rojo H, Martinez A, et al. Efficacy of a vancomycin solution to prevent bacteremia associated with an indwelling central venous catheter in neutropenic and non-neutropenic cancer patients. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:196–200. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199703)28:3<196::aid-mpo8>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henrickson KJ, Axtell RA, Hoover SM, Kuhn SM, Pritchett J, Kehl SC, Klein JP. Prevention of central venous catheter-related infections and thrombotic events in immunocompromised children by the use of vancomycin/ciprofloxacin/heparin flush solution: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind trial. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1269–1278. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garland JS, Alex CP, Henrickson KJ, McAuliffe TL, Maki DG. A vancomycin-heparin lock solution for prevention of nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill neonates with peripherally inserted central venous catheters: a prospective, randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e198–e205. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozturk MA, Gunes T, Koklu E, Cetin N, Koc N. Oral nystatin prophylaxis to prevent invasive candidiasis in neonatal intensive care unit. Mycoses. 2006;49:484–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaufman D, Boyle R, Hazen KC, Patrie JT, Robinson M, Donowitz LG. Fluconazole prophylaxis against fungal colonization and infection in preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1660–1666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufman D, Boyle R, Hazen KC, Patrie JT, Robinson M, Grossman LB. Twice weekly fluconazole prophylaxis for prevention of invasive Candida infection in high-risk infants of <1000 grams birth weight. J Pediatr. 2005;147:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manzoni P, Stolfi I, Pugni L, Decembrino L, magnani C, Vetrano G, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of prophylactic fluconazole in preterm neonates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2483–2495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saiman L, Ludington E, Pfaller M, Rangel-Frausto S, Wiblin RT, Dawson J, et al. Risk factors for candidemia in neonatal intensive care unit patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:319–324. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benjamin DK. First, do no harm. Pediatrics. 2008;121:831–832. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersen DH, Blanc WA, Crozier DN, Silverman WA. A difference in mortality rate and incidence of kernicterus among premature infants allotted to two prophylactic antibacterial regimens. Pediatrics. 1956;18:614–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]