Abstract

Objective

To describe the development of a novel couple-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for adult anorexia nervosa (AN) called Uniting Couples (in the treatment of) Anorexia Nervosa (UCAN).

Method

We review the state of the science for the treatment of adult AN, the nature of relationships in AN, our model of couple functioning in AN, and the development of the UCAN intervention.

Results

We present the UCAN treatment for patients with AN and their partners and discuss important considerations in the delivery of the intervention.

Discussion

With further evaluation, we expect that UCAN will emerge to be an effective, acceptable, disseminable, and developmentally tailored intervention that will serve to improve both core AN pathology as well as couple functioning.

Introduction

Status of Evidence Base for the Treatment of Adult Anorexia Nervosa (AN)

Despite the pernicious effects of AN and extensive efforts over many years to enhance treatment, effective options for adults with AN in adults remain limited. Preliminary evidence exists for the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) after weight restoration,1 and additional preliminary evidence suggests that specialist supportive-clinical management is more effective than interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), with CBT holding a middle position.2, 3 Family-based approaches have been shown to be effective in younger non-chronic AN patients.4 Despite the efficacy of family-based approaches for youth, very few studies have evaluated treatments which leverage the power of family support for adults with AN. In reviewing the state of treatment, we concluded that a critical need exists for developmentally appropriate, innovative interventions for adults with AN, that target the core pathology of the illness and leverage the support of partners in recovery.

The Importance of Relationships in AN

Stereotypes of individuals with AN not entering committed relationships and not having children have proven untrue.5, 6 To the contrary, a substantial proportion of people presenting for treatment for AN report being in committed relationships. Not only are adults with AN frequently in relationships, but patients emphasize the centrality of their partners in the recovery process. For example, in a follow-up study of 70 women who had been treated for AN 10 years earlier, we explored the women’s perceptions of factors contributing to their recovery.7 The most commonly cited factor associated with recovery was having a supportive partner. In fact, women with AN reported that a supportive relationship was the “driving force” in their recovery. The seeming importance of supportive relationships across the lifespan in treating AN is noteworthy as adolescents with AN also stress the importance of friends and supportive relationships in recovery. 8 These observations further fueled our exploration of the utility of a couple-based therapeutic approach in the treatment of AN.

Global Marital Adjustment/Distress in Persons with Anorexia Nervosa

Whereas having a supportive relationship appears to be important in recovering from AN, a large body of literature indicates that having a distressed, critical, or hostile intimate relationship has the opposite effect for individuals with a variety of types of psychopathology. Such negative relationships serve as a significant source of stress on the individual and predict individual relapse.9 Thus, it is important to understand whether the marital relationships for patients with AN typically serve as an important source of support or, to the contrary, create additional stress. Findings to date indicate that many adults with eating disorders experience a variety of difficulties in their marriages or committed relationships, and marital distress is common in relationships in which one spouse has an eating disorder.10–13 For example, in a review of 12 cases,13 seven patients were separated or divorced, and three reported experiencing significant marital difficulties. Similarly, in a study of mothers with eating disorders,14 10 of 11 reported significant marital distress. Thus, in each of these two small investigations, over 80% of the patients demonstrated notable marital difficulties. Furthermore, these marital difficulties are related to additional family distress. Maritally distressed mothers with eating disorders also tend to have children with behavior problems,10, 15 and these children often become centrally involved in their parents’ marital conflict.10 This body of work contributed to our perception that assisting partners in developing an appropriately supportive stance may be an important component of treatment for adult AN.

Communication in Couples with Anorexia Nervosa

In addition to global marital adjustment, important, specific domains of relationship functioning such as communication and sexual functioning have been explored in patients with AN. Communication within couples experiencing AN is important for at least two reasons. First, communication is central in the provision of support from a partner, and support appears to be valuable in the recovery process of AN. That is, the two major categories of support—instrumental and emotional—both rely upon effective communication between partners.16 Second, the effects of communication are profound on a more general level; a large body of research indicates that in terms of relationship variables, communication is the most consistent predictor of overall, long term relationship functioning.17 Although research on communication within couples including a partner with an eating disorder is limited, women with eating disorders (a combined AN and bulimia nervosa sample) and their spouses have been compared with maritally distressed and non-distressed groups while engaging in a conflictual and nonconflictual conversation. The eating disorder couples engaged in more negative nonverbal communication than the non-distressed couples, but less than the distressed couples.18 The eating disorder couples also employed fewer constructive communication skills than the non-distressed couples. Thus, couples including a woman with an eating disorder appear to function, on average, midway between non-distressed and maritally distressed couples in terms of communication, which is a critical skill for functioning well as a unit in order to address specific issues associated with AN and the broader relationship. Effective communication is critical for couples to be able to address many aspects of AN; yet, couples with a member with AN often experience communication difficulties. Based on these observations, we reasoned that specifically targeting communication in couples with AN may be an important component of any treatment for AN that includes the couple.

Sexual Functioning in Couples with Anorexia Nervosa

A second specific domain of importance in the relationships of individuals with AN is sexual functioning. Not only is healthy sexual functioning important for relationship quality in general, but for individuals with AN, distorted body image, body dissatisfaction, and shame are central to the disorder 19–22 and can severely impact sexual functioning. The extant findings point to considerable concerns in the area of sexuality for patients with AN. For example, 80% of AN patients reported primary or secondary difficulties in their sexual relationship.23 Pinheiro et al. reported that decreased sexual desire (66.9%) and increased sexual anxiety (59.2%) were common in women with eating disorders and women with restricting and purging AN had a higher prevalence of loss of libido than women with bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise24. Likewise, approximately 40% of a mixed eating disorder sample reported sexual discord with their partner.25 We found that women with AN or depression were more likely to have had sex than postpartum women in the previous fortnight, but they were also more likely to report sexual problems than postpartum women.26 One of the few investigations assessing sexual functioning of partners involved mixed diagnosis eating disorder patients and their spouses over the course of a partial hospitalization program.27 Two hundred women and their partners completed the Waring Intimacy Questionnaire 28 at admission to and discharge from partial hospitalization. Patients’ ratings generally were less favorable than spouses on affection, cohesion, sexuality, and identity (analogous to self-esteem). Sexuality and intimacy scores were low in patients and remained low throughout treatment.

Not only are sexual concerns frequent among individuals with AN, but these sexual concerns covary with other aspects of AN. More specifically, sexual satisfaction in AN is inversely related to degree of caloric restriction;29 similarly, the greater the weight loss, the greater the loss of sexual enjoyment.30 Also the magnitude of sex drive tends to increase with weight restoration.31 Although tentative, existing findings indicate that sexual functioning is disturbed among patients with AN. Based on these observations, we adopted the stance that not only is it important for overall quality of life to help these patients and their partners experience an optimal sexual relationship, but that intervening in the sexual domain may confer additional benefits in addressing core AN body-related concerns.

Caregiver Experiences and the Marital Relationship

A body of literature on caregiving in AN is beginning to emerge. Most studies focus on parents; however, partners have been assessed in some investigations. In general, caregivers of individuals with AN report greater burden than relatives of those with BN32 and poorer general health and greater caregiving difficulties than caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia.33 Family members of those with AN report salient issues including “loss” of the premorbid relationship (i.e., “She’s not the same wife she used to be”), the negative effects of AN on the family, dealing with difficult eating related behaviors, the dependent nature of patients, social stigma, shame, and guilt.33 In a study focusing on caregiving among parents of adult AN inpatients, the caregivers reported feelings of distress, guilt, and helplessness—not knowing how to be of assistance to the patient,34 suggesting that caregiving in AN is associated with negative self perception, stress, and uncertainty regarding how best to help. Although studies specific to caregiving by partners are lacking, many of the issues that arise likely apply to all caregivers. These common issues are compounded by other domains that are specific to intimate relationships such as the impact on children and social functioning—areas which have not been adequately addressed in the literature. Caregiving in AN is challenging. Whereas family members want to be of assistance, often they do not know how to help the patient. We proposed that couple-based interventions which train couples how to work effectively together to approach AN have the potential to improve caregiving and transform the relationship into a source of effective support and a tool for change.

The Need for Efficacious Couple-Based Interventions for AN

At present, there is little empirical evidence supporting efficacious interventions for adults with AN. The above discussion points to the centrality of intimate relationships which might be leveraged in developing effective interventions for AN. Although family-based interventions are useful in treating adolescents with AN, developmentally appropriate adaptations of such treatments to include committed partners in the treatment of adult AN have not been evaluated.35 The importance of attending to the couple’s relationship is suggested by the finding that patients with AN report that supportive partners were critical to recovery.7 Whereas a supportive, committed relationship appears to be central when AN recovery does occur, many individuals with AN report relationships that appear to function as an additional source of stress rather than support. That is, patients with AN frequently report global marital distress, poor communication, and high levels of sexual concerns. Reciprocally, whereas family members report that they want to be of assistance, they often feel helpless and uncertain regarding what to do to be of help. Instead of feeling efficacious, family members often feel distressed and guilty about the AN, with a high level of caregiver burden. Given the potential value of a supportive partner in the treatment of AN, yet the reported difficulties in committed relationships, our goal was to develop efficacious interventions including the partner in the treatment of adult AN. To do this we drew from couple-based cognitive-behavioral therapy which has demonstrated efficacy in addressing relationship concerns and various forms of psychopathology and health problems.

Cognitive-Behavioral Couple Therapy (CBCT)

The most widely researched marital/couple intervention is cognitive-behavioral couple therapy (CBCT).36 CBCT targets relationship functioning by teaching partners communication and problem-solving skills, helping to enhance understanding of relationship interactions, and addressing emotions in an adaptive manner. CBCT also includes behavioral changes to increase the frequency of specific positive interactions while minimizing targeted negative exchanges focal to the couple. The effects of CBCT on marital functioning have been widely researched. Numerous research studies have compared CBCT with wait list control conditions and have consistently shown that CBCT is more efficacious than a waiting list in improving marital functioning.37–42 In a meta-analysis of 17 controlled outcome studies, Hahlweg and Markman 43 found the mean effect size of CBCT to be 0.95, relative to placebo or waiting list conditions. In an updated meta-analysis, Baucom, Hahlweg, and Kuschel 44 found a within group effect size of 0.82 for CBCT and a between group effect size of 0.72 for CBCT relative to placebo or waiting list conditions. Thus, on the basis of extant treatment outcome studies, CBCT has been classified as an efficacious treatment for marital distress.45

Couple-based interventions founded on cognitive-behavioral principles can also be used when one partner is suffering from a psychiatric illness. These interventions are based on the premise that individual psychopathology occurs in a context, and effective intervention includes working within an individual’s natural social environment to optimize change. Given that partners typically are central to the individual’s environment, intervening on a couple-level can promote and maintain needed changes for the individual. Whereas many partners are willing and even eager to be of assistance when an individual experiences some form of psychopathology, frequently they report not knowing how to help and express fears of inadvertently making matters worse. These concerns emerge in both well-adjusted and distressed relationships. Thus, the therapist must have a clear understanding of how to employ the partner meaningfully in treating disorders such as AN.

Baucom et al.45 note that when working with a couple in which one person is experiencing psychological problems such as AN, therapists can choose among three couple-based intervention strategies depending upon the goals for treatment: (1) partner-assisted interventions, (2) disorder-specific interventions, or (3) general couple therapy. Which intervention is chosen depends on the extent and the manner in which the relationship will be addressed in treatment. In partner-assisted interventions, the partner plays the role of a surrogate therapist or coach in assisting the identified patient. These interventions typically operate within a cognitive-behavioral framework in which the patient has homework assignments, and the partner helps the patient in completing these assignments outside of the therapy session. In such interventions, the relationship is not the focus of change; rather, the partner is helping the patient make needed individual changes. In disorder-specific interventions, the couple’s relationship is targeted, but only to the degree to which it is related to the patient’s individual difficulties; the couple’s broader relationship is not the focus of intervention. That is, disorder-specific interventions focus “on the ways in which a couple interacts or addresses situations related to the individual’s disorder that might contribute to the maintenance or exacerbation of the disorder” (p. 63, 45). Partner-assisted and disorder-specific interventions can be employed in both satisfied and distressed couples. General couple therapy targets marital distress with the intent of assisting the treatment of an individual’s disorder. Such treatments are based on the notion that poor relationship functioning is a broad, chronic stressor that contributes to the development or maintenance of individual symptoms, and, thus, decreasing relationship distress can improve individual functioning. Consequently, general couple therapy would be employed only when the couple has significant relationship distress, whereas partner-assisted and disorder-specific interventions could be employed with any couple. These interventions have been used successfully with several psychiatric disorders, 45 including depression 46–50 and anxiety disorders. 51–56 Given the high comorbidity of AN and depression57 and anxiety disorders,58–60 these results lend further support to the potential value of an adaptation of a couple-based intervention for AN.

We have also successfully integrated CBCT with Dialectical Behavior Therapy in a disorder-specific couple intervention for couples in which at least one partner had experienced chronic difficulties in emotion regulation.61, 62 CBCT also has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of substance abuse, sexual disorders, and schizophrenia.45 Couple-based interventions have also proven successful for medical conditions including various forms of cancer, coronary heart disease, and osteoarthritis.63–67 Given CBCT’s demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of various psychiatric and medical conditions, a well-designed couple-based intervention might be a valuable tool in creating a developmentally appropriate intervention for adult AN in the context of their social and interpersonal environment.

What is UCAN?

UCAN is based on the perspective that although one member of the couple has AN, the disorder occurs in an interpersonal and social context. For patients who are married or have a committed partner, this partner is a central part of that social environment which can contribute to the alleviation, maintenance, and/or exacerbation of AN. Whereas many partners want to be of assistance to a patient experiencing AN, they frequently do not know how to help and, at times, may inadvertently exacerbate the patient’s maladaptive patterns associated with AN. Consequently, our intervention helps the couple work together as an effective team to approach the eating disorder.

A Model of Couple-Based Interventions- UCAN

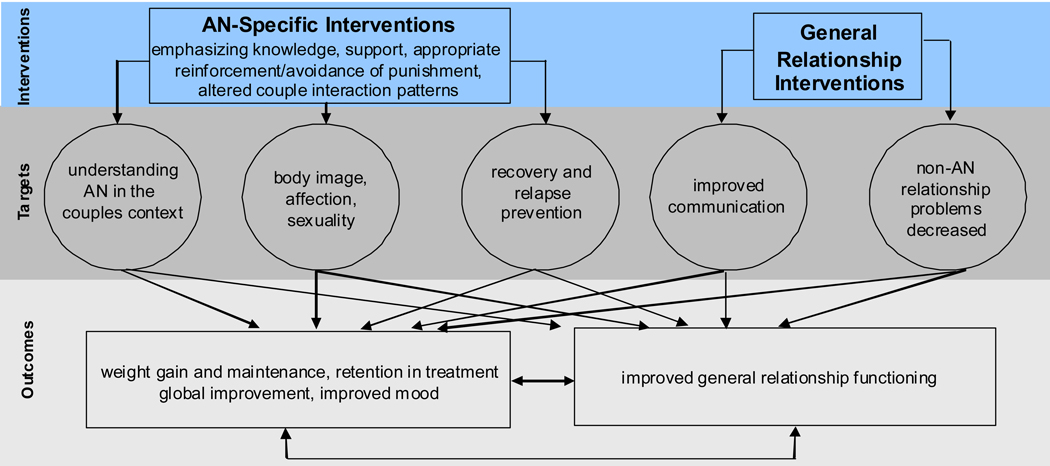

Figure 1 presents our conceptualization of UCAN’s specific interventions, potential mediators of those interventions, and domains that are likely to be affected by our interventions. The left side of the model includes AN-specific domains: understanding AN in the couples context (encompassing all core AN symptoms), body image, affection, and sexuality, and relapse and recovery. By including the partner in the intervention, we posit several mechanisms as central in affecting change in our dependent measures, including: providing an overall source of support to the patient; reinforcing appropriate eating and other health-related behaviors while avoiding punishment; functioning effectively as a couple in addition to working individually to approach AN; and increasing comfort and acceptance of the body without providing inappropriate reassurance. On the right side of the model are the general relationship functioning domains. Intervention in these areas not only impacts general functioning, but also provides additional skills for addressing AN-specific concerns. Likewise, AN is a stressor on most relationships, and as AN improves, the overall relationship is likely to benefit as well.

Figure 1.

Effects of UCAN on AN and General Relationship Functioning

UCAN Session Content

Phase 1: Creating a Foundation for Later Work

The first phase of UCAN provides the foundation for the couple’s later work in addressing the AN more effectively. To this aim, this initial phase of treatment focuses on three goals: (1) understanding the couple’s experience of AN; (2) providing psychoeducation about AN and the recovery process; and (3) teaching the couple effective communication skills. Because every couple has a unique experience of AN and their relationship more broadly, UCAN begins with an extensive assessment of the couple’s relationship history, both partner’s experience of AN, and how AN has influenced and been influenced by the couple’s relationship. The psychoeducation component is designed to provide both members of the couple with a comprehensive and shared understanding of AN (e.g., symptoms, features, biological and environmental risk factors, associated symptoms and comorbidities, and the nature of the recovery process). The resultant shared understanding sets the stage for the couple’s greater sense of teamwork, which is then further cultivated through the teaching of essential communication and problem-solving skills that are instrumental in successful couple-based interventions. Through didactic instruction and extensive in- and out-of-session practice, the couple learns how to express thoughts and feelings, listen responsively, and solve problems/make decisions as a unit. With the combination of a united perspective and effective communication and problem-solving skills, the couple is well positioned to address topic areas that are central to AN as described below.

Phase 2: Addressing Anorexia Nervosa within a Couples Context

A fundamental treatment goal for individuals with AN is the resumption of a healthy body weight and the development of healthy eating behaviors (e.g., avoidance of restricting and purging). Therefore, the second phase of UCAN targets the couple’s relationship and interactions around the eating disorder to create an effective support system for the patient as she/he addresses the AN in individual treatment. Phase 2 begins by guiding the couple through a consideration of the various features of AN they find most challenging (e.g., restricting, purging, binge eating, secrecy, etc.). Drawing upon their shared conceptualization of AN, the couple uses their communication skills to develop ways of responding to these challenges more effectively as a team. For example, the couple is encouraged to consider how the partner can support the patient in eating meals without adopting a role of strict monitor or commenting inappropriately on what the patient has not eaten or “should” be eating, etc. By developing ways the patient and partner can discuss eating in a way that promotes recovery, the couple is better able to develop more positive interactions around meal times and eating overall within their relationship, which can contribute to the patient’s development of healthier eating and extricate the partner from an uncomfortable and potentially unproductive role. UCAN provides considerable flexibility in developing the optimal approach, as every couple is different, and the partners need to work collaboratively with the aid of the therapist to develop the optimal approach.

Once the couple has developed more positive and effective ways that the partner can support the patient’s healthier eating habits, UCAN focuses on how the couple interacts more broadly around food and meals within a variety of eating contexts. The therapist guides the couple through an analysis of their relationship patterns around eating disorder areas in order to help the couple create a relational context that supports the positive health-promoting changes the patient is making. For example, the couple is asked to reflect upon what meal times have been like both within and outside of the home, and consider the possible roles that other individuals (e.g., children, friends, or colleagues) might play in alleviating or increasing stress that the couple may experience around eating. Based on these observations, the couple uses their decision-making skills to develop a more effective approach to eating together as a couple/family both within and outside of the home, and responding to other individuals appropriately within these contexts. This same approach is applied to other features of AN such as exercise, purging, restricting, etc.

Phase 2 continues by broadening the focus of AN features the couple finds challenging in the recovery process to include body image and sexual issues as they relate to the eating disorder. Through a consideration of common challenges that couples can face when communicating about body image, the couple’s awareness of problematic interaction patterns around the patient’s body image within their own relationship is heightened. To help counter these problematic interaction patterns, the couple is encouraged to use their communication skills while the patient shares her/his experience of body image with the partner. Because body image distortions and body dissatisfaction can be two of the most puzzling features of AN for the partner, it is important that the couple be provided with this opportunity to build a greater sense of understanding and empathy for one another’s body image experiences. The partner is also provided with the opportunity to discuss his/her own body image challenges. Building on this enhanced mutual understanding, the couple is then guided to develop more effective ways to communicate or interact around body image within their relationship through the use of their decision-making skills. Notably, this work in UCAN is not designed to “fix” body image problems associated with AN, as this can be one of the most intractable symptoms of the illness. Rather, it is expected that this work will help the partner gain a greater understanding and empathy for the symptom, help the patient feel more understood in this domain, and assist the couple in addressing the topic more directly and effectively in their relationship.

The body image work is a natural entrée into the couple’s physical relationship. Given the frequency with which sexual difficulties emerge in couples in which a partner has AN, phase 2 concludes with a consideration of how the couple’s physical relationship can impact and be impacted by the patient’s experience of a negative body image and the eating disorder more broadly. This work begins with a consideration of the challenges couples can experience within their physical relationships generally and then related to AN. The couple is invited to discuss their own experiences in this domain. Using their enhanced communication skills, the couple discusses physical affection and sex within their relationship, addresses any concerns they might have, and develops possible ways to enhance these domains. Because couples confronting AN vary widely in their physical and sexual relationships (ranging from no physical contact to mutually enjoyable sex), it is critical to tailor the intervention to the couple’s current level of functioning. In this manner, the couple is assisted in developing healthier patterns within their physical relationship that take into account the patient’s current experience of the eating disorder and body image more specifically.

Phase 3: Relapse Prevention and Termination

The final phase of UCAN brings the treatment to a close by discussing relapse prevention and the couple’s next steps following UCAN. Phase 3 begins with psychoeducation about the process of recovery and relapse prevention, including slips versus relapses, and high risk situations and conditions for the patient and the couple. The couple is then guided in generating specific examples of these concepts for the patient, the partner, and their relationship, so the couple has a clear sense of what monitor as they move beyond UCAN. Then, the couple is asked to use their decision-making skills to develop effective ways to respond to selected high risk situations and conditions with the goal of preventing slips and relapses. The couple is also encouraged to consider how they can effectively respond to slips and relapses if they do occur. Finally, the couple’s treatment experience in UCAN is reviewed and the couple is asked to brainstorm how they will continue working as a team against AN in the future. Thus, UCAN addresses multiple aspects of AN from a couple perspective, leveraging the patient’s key relationship in a variety of ways to address the eating disorder. By integrating UCAN into a broader intervention for AN, we acknowledge the critical role that a committed partner can play in recovery from AN and anticipate that it will lead to more favorable and lasting treatment gains.

Considerations in Delivering UCAN

UCAN was developed for individuals who are in committed relationships and are living together as an interdependent couple. Given that the intervention focuses on highly personal issues, UCAN is designed to be used with individual couples rather than in a group format. Patients and partners can be of any sex or sexual orientation. UCAN addresses difficult AN-related and relationship issues; thus, both partners need to commit to the entire course of 22 sessions (as defined in our research trial) and be supported by the therapist at points when they experience treatment as particularly challenging. Prior to UCAN, individuals with AN and their partners often have avoided discussing eating-disorder related issues, and doing so can be distressing to both partners, even in a supportive therapeutic context. In addition, UCAN is designed to be an augmentation strategy. Unlike some family-based treatments for adolescent AN,4, 68, 69 UCAN does not require the partner to take significant responsibility for monitoring patient weight and eating. Instead, UCAN takes a more developmentally appropriate approach and helps couples avoid the power imbalance that can result from putting the partner in a position of complete authority relative to the patient and the AN. Couples work collaboratively with the UCAN therapist to tailor the optimal stance of the partner with reference to eating and weight restoration. For this reason, UCAN was developed as an important component of a multifaceted intervention rather than a sole intervention for AN. Working in close collaboration with an individual therapist, a dietitian, and a treating psychiatrist can allow the UCAN therapist to focus primarily on working with the couple towards recovery. UCAN focuses on how the couple as a team can approach AN together, but it is not assumed that UCAN alone is sufficient to address all aspects of AN treatment. Thus, UCAN is appropriate for couples who receive treatment in a comprehensive, multidisciplinary context.

Working with Difficult Couples: Clinical Considerations

Couples seeking UCAN have in common that one partner has AN, yet these couples vary significantly on both individual and relationship factors that appear to influence the course of treatment. Although we do not yet have empirical evidence regarding which couples benefit most from UCAN, our clinical observations suggest that there are certain factors that might call for longer treatment or that could interfere with optimal treatment gains if not handled skillfully. First, couples seeking UCAN treatment differ in their degree of relationship satisfaction/distress and their ease in working together around the patient's AN. If the couple enters treatment with a high level of relationship distress, the person with AN can experience difficulty sharing intimate details about AN with her/his partner if the relationship does not feel safe and the couple has frequent negative interactions. Likewise, the partner can find it difficult to experience empathy about AN and support the patient if the couple does not interact in a caring way more generally. On the other hand, our previous investigations indicate that we are successful in working with a wide range of couples around various individual psychological and health issues, frequently improving their relationship functioning. That is, giving the couple a specific targeted area to address can provide an opportunity for them to learn to work together as an effective team more broadly. For example, in a previous couple-based investigation in which one partner experienced severe emotional dysregulation problems, our findings indicate a notable increase in partners' relationship satisfaction at the end of treatment and at follow-up.62 Likewise, in our initial work with couples in which the female partner has breast cancer, our intervention resulted in notable effects sizes for treatment relative to treatment as usual for both women and men's relationship satisfaction. 65 Furthermore, in our work with cardiac patients, our couple-based intervention was particularly beneficial to more maritally distressed couples in promoting health behavior changes.70 In none of these investigations have there been instances in which we needed to terminate our couple-based intervention focusing on individual psychological difficulties or health concerns due to the relationship distress level of a couple. Thus, whereas a high level of relationship distress can prove to be a challenge to both the couple and the therapist in addressing the patient’s AN, UCAN provides an opportunity to assist the couple not only in addressing AN, but also in improving general relationship functioning.

Individual factors also appear to influence the ease with which treatment proceeds. Often conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders or symptoms co-occur with AN and are an inevitable target of treatment. Our experience is that a skilled therapist can address these concerns as they influence the ease with which the patient and couple approach difficult topics, attempt to avoid discussion, or attempt behavior change. Perhaps more challenging is the impact that patient Axis II symptomatology (in particular, difficulty regulating emotions) can have on a smooth course of treatment. When facing difficult issues in treatment, emotionally dysregulated patients might miss sessions, decide (at least temporarily) to drop out of treatment, increase eating-disordered behavior (e.g., hidden use of diuretics or laxatives) that at times require short term hospitalization, or engage in other maladaptive emotion regulation behaviors such as heavy alcohol use that disrupt family functioning. It is important to recognize that emotion dysregulation during treatment occurs not only when addressing eating-related issues, but can be triggered by related issues as well, such as addressing physical affection and sexuality which often are tied to body image. Likewise, patients with borderline traits frequently have fears of abandonment which can be activated as the time-limited UCAN intervention comes to a close. Our experience is that with the support of a skilled UCAN therapist and a quick and integrated response from the full treatment team, typically we are able to help the couple and patient through these difficult times in treatment.

As the empirical treatment literature demonstrates, treating adult AN is challenging. Co-morbid Axis I and Axis II disorders/symptoms are frequently a part of the reality of these patients and, thus, are a part of the treatment for the couple in UCAN. Likewise, patients’ individual issues can contribute to relationship distress for the couple more generally, as well as relationship discord being a stressor on the person with AN. As a result, a UCAN therapist needs to have a good understanding of AN and related individual disorders, as well as being skilled in addressing couple issues that relate to individual psychopathology. While complex, this reciprocal interaction between individual and relationship functioning is, in essence, what gives UCAN its distinctive and potentially valuable contribution to the treatment of AN.

Discussion

UCAN is currently undergoing evaluation in a clinical trial. Ultimately, we expect that UCAN will be readily adaptable for couple interventions for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder as well. An adaptation for the Latino population is currently underway (Reyes, personal communication). We foresee that UCAN will have immediate applicability for adults with AN and their partners and has the potential to change the standard of practice and enhance both retention in treatment and outcome. Whereas UCAN will continue to evolve, we believe that the mindful inclusion of partners in treatment acknowledges that AN exists on both the personal and interpersonal level and represents an innovative and important step forward in improving outcomes of this complex and often treatment-resistant disorder.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (R01MH082732: Bulik/Baucom) as well as CTSA grant UL1RR025747 and GCRC grant M01RR00046.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pike K, Walsh B, Vitousek K, Wilson G, Bauer J. Cognitive behavior therapy in the posthospitalization treatment of anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2046–2049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntosh V, Jordan J, Carter F, Luty S, McKenzie J, Bulik C, et al. Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:741–747. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntosh VV, Jordan J, Luty SE, Carter FA, McKenzie JM, Bulik CM, et al. Specialist supportive clinical management for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 2006 Dec;39:625–632. doi: 10.1002/eat.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell GFM, Szmukler GI, Dare C, Eisler I. An evaluation of family therapy in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:1047–1056. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinch M, Isager T, Tolstrup K. Anorexia nervosa and motherhood: reproduction pattern and mothering behavior of 50 women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;77:611–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb05175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulik C, Sullivan P, Fear J, Pickering A, Dawn A. Fertility and reproduction in women with anorexia nervosa: a controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;2:130–135. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tozzi F, Sullivan PF, Fear JL, McKenzie J, Bulik CM. Causes and recovery in anorexia nervosa: the patient's perspective. Int J Eating Disord. 2003;33:143–154. doi: 10.1002/eat.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilsson K, Hagglof B. Patient perspectives of recovery in adolescent onset anorexia nervosa. Eat Disord. 2006;14:305–311. doi: 10.1080/10640260600796234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooley JM, Hiller JB. Family relationships and major mental disorder: Risk factors and preventive strategies. In: Sarason BR, Duck S, editors. Personal Relationships: Implications for Clinical and Community Psychology. New York: John Wiley; 2001. pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franzen U, Gerlinghoff M. Parenting by patients with eating disorders: Experiences with a mother-child group. Eat Disord. 1997;5:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodes M, Timini S, Robinson P. Children of mothers with eating disorders: A preliminary study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 1997;5:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Buren DJ, Williamson DA. Marital relationships and conflict resolution skills of bulimics. Int J Eating Disord. 1988;7:735–741. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodside D, Shekter-Wolfson L. Parenting by patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 1990;9:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Timini S, Robinson P. Disturbances in children of patients with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 1996;4:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbin J, Williamson D, Stewart T, Reas D, Thaw J, Guarda A. Psychological adjustment in the children of mothers with a history of eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2002;7:32–38. doi: 10.1007/BF03354427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutrona CE, Cohen B, Igram S. Contextual determinants of the perceived supportiveness of helping behaviors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:553–562. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychol Bull. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van den Broucke S, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H. Marital intimacy in patients with an eating disorder: a controlled self-report study. Br J Clin Psychol. 1995;34(Pt 1):67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seeger G, Braus DF, Ruf M, Goldberger U, Schmidt MH. Body image distortion reveals amygdala activation in patients with anorexia nervosa -- a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci Lett. 2002;326:25–28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000

- 21.Gupta M, Gupta A, Schork N, Watteel G. Perceived touch deprivation and body image: some observations among eating disordered and non-clinical subjects. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:459–464. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00146-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grabhorn R, Stenner H, Kaufbold J, Overbeck G, Stangier U. Shame and social anxiety in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2005;51:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raboch J, Faltus F. Sexuality of women with anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinheiro AP, Raney TJ, Thornton LM, Fichter MM, Berrettini WH, Goldman D, et al. Sexual functioning in women with eating disorders. Int J Eating Disord. 2009 doi: 10.1002/eat.20671. [Epub before print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan CD, Wiederman MW, Pryor TL. Sexual functioning and attitudes of eating-disordered women: a follow-up study. J Sex Marital Ther. 1995;21:67–77. doi: 10.1080/00926239508404386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter F, Carter J, Luty S, Jordan J, McIntosh V, Bartram A, et al. What is worse for your sex life: Starving, being depressed, or a new baby? Int J Eating Disord. 2007;40:664–667. doi: 10.1002/eat.20394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodside DB, Lackstrom JB, Shekter-Wolfson L. Marriage in eating disorders comparisons between patients and spouses and changes over the course of treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waring E, Reddon J. The measurement of intimacy in marriage: the Waring Intimacy Questionnaire. J Clin Psychol. 1983;39:53–57. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198301)39:1<53::aid-jclp2270390110>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiederman MW, Pryor T, Morgan CD. The sexual experience of women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 1996;19:109–118. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199603)19:2<109::AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beumont P, Abraham S, Simson K. The psychosexual histories of adolescent girls and young women with anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med. 1981;11:131–140. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700053344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan JF, Lacey JH, Reid F. Anorexia nervosa: changes in sexuality during weight restoration. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:541–545. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199907000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santonastaso P, Saccon D, Favaro A. Burden and psychiatric symptoms on key relatives of patients with eating disorders: a preliminary study. Eat Weight Disord. 1997;2:44–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03339949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Treasure J, Murphy T, Szmukler G, Todd G, Gavan K, Joyce J. The experience of caregiving for severe mental illness: a comparison between anorexia nervosa and psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:343–347. doi: 10.1007/s001270170039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitney J, Murray J, Gavan K, Todd G, Whitaker W, Treasure J. Experience of caring for someone with anorexia nervosa: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:444–449. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bulik CM, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, Lohr KN. Anorexia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eating Disord. 2007;40:293–309. doi: 10.1002/eat.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baucom DH, Epstein N. Cognitive-behavioral marital therapy. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baucom DH. A comparison of behavioral contracting and problem-solving/communications training in behavioral marital therapy. Behavior Therapy. 1982;13:162–174. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baucom DH. Treatment of marital distress from a cognitive behavioral perspective. annual conference of the North Carolina Psychological Association; 1986 October; Asheville, NC. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baucom DH, Sayers SL, Sher TG. Supplementing behavioral marital therapy with cognitive restructuring and emotional expressiveness training: an outcome investigation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:636–645. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hahlweg K, Revenstorf D, Schindler L, Brengelmann JC. Current issues in marital therapy. Analisis y Modificacion de Conducta. 1982;8:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobson NS, Follette WC, Revenstorf D, Baucom DH, Hahlweg K, Margolin G. Variability in outcome and clinical significance of behavioral marital therapy: a reanalysis of outcome data. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:497–504. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder DK, Wills RM. Behavioral versus insight-oriented marital therapy: Effects on individual and interspousal functioning. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:39–46. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hahlweg K, Markman HJ. Effectiveness of behavioral marital therapy: empirical status of behavioral techniques in preventing and alleviating marital distress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:440–447. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baucom D, Hahlweg K, Kuschel A. Are waiting-list control groups needed in future marital therapy outcome research? Behav Ther. 2003;34:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baucom DH, Shoham V, Mueser KT, Daiuto AD, Stickle TR. Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:53–88. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beach SRH, O'Leary KD. Treating depression in the context of marital discord: Outcome and predictors of response of marital therapy versus cognitive therapy. Behavior Therapy. 1992;23:507–528. [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Leary KD, Beach SRH. Marital therapy: A viable treatment for depression and marital discord. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:183–186. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emanuels-Zuurveen L, Emmelkamp PM. Individual behavioral-cognitive therapy v. marital therapy for depression in maritally distressed couples. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:181–188. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Fruzzetti AE, Schmaling KB, Salusky S. Marital therapy as a treatment for depression. J Consulti Clini Psychol. 1991;59:547–557. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leff J, Vearnals S, Brewin CR, Wolff G, Alexander B, Asen E, et al. The London depression intervention trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2000:177. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehta M. A comparative study of family-based and patient-based behavioural management in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:133–135. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emmelkamp P, de Lange I. Spouse involvement in the treatment of obsessivecompulsive patients. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21:341–346. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emmelkamp P, de Haan E, Hoodguin C. Marital adjustment. and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:55–60. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cobb J, Mathews A, Childs-Clarke A, Bowers C. The spouse as a cotherapist in the treatment of agoraphobia. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:282–287. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emmelkamp P, van Dyck R, Bitter M, Heins R, Onstein E, Eisen B. Spouse-aided therapy with agoraphobics. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:51–56. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arnow B, Taylor C, Agras W, Telch M. Enhancing agoraphobia treatment outcome by changing couple communication patterns. Behav Ther. 1985;16:452–467. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandez-Aranda F, Pinheiro A, Tozzi F, Thornton L, Fichter M, Halmi K, et al. Symptom profile and temporal relation of major depressive disorder in females with eating disorders. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2007;41:24–31. doi: 10.1080/00048670601057718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaye W, Weltzin T, Hsu L, Bulik C, McConaha C, Sobkiewicz T. Patients with anorexia nervosa have elevated scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Int J Eating Disord. 1992;12:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halmi K, Sunday S, Klump K, Strober M, Leckman J, Fichter M, et al. Obsessions and compulsions in anorexia nervosa subtypes. Int J Eating Disord. 2003;33:308–319. doi: 10.1002/eat.10138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Godart N, Flament M, Perdereau F, Jeammet P. Comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Int J Eating Disord. 2002;32:253–270. doi: 10.1002/eat.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kirby JS, Baucom DH. Integrating dialectical behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral couple therapy: A couples skills group for emotion dysregulation. Cog Behav Practice. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kirby JS, Baucom DH. Treating emotional dysregulation in a couples context: A pilot study of a couples skills group intervention. J Marital Fam Therapy. 2007;33:375–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Sutton L, Dalton JA, Baucom DH, Pope MS, et al. Partner-guided cancer pain management at end-of-life: A preliminary study. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2005;29:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keefe FJ, Blumenthal J, Baucom DH, Affleck G, Waugh R, Caldwell D, et al. Effects of spouse-assisted coping skills training and exercise training in patients with osteoarthritic knee pain: A randomized controlled study. Pain. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.022. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baucom DH, Heinrichs N, Scott JL, Gremore TM, Kirby JS, Zimmermann T, et al. Couple-based interventions for breast cancer: Findings from three continents. 39th Annual Convention of the Assocation for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; 2005 November; Washington, D.C. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Gremore TM, Wiesenthal N, Aldridge W, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18:276–283. doi: 10.1002/pon.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, Hurwitz H, Moser B, Patterson E, et al. Partner-assisted emotional disclosure for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: results from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2009;115:4326–4338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras W, Dare C. Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: A family-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lock J. Treating adolescents with eating disorders in the family context. Empirical and theoretical considerations. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;11:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(01)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sher TG, Baucom DH. Mending a broken heart: A couples approach to cardiac risk reduction. App Prevent Psychol. 2001;10:125–133. [Google Scholar]