Abstract

Multiple studies suggest that cystatin C (CysC) has a role in Alzheimer's disease (AD) and a decrease in CysC secretion is linked to the disease in patients with a polymorphism in the CysC gene. CysC binds amyloid β (Aβ) and inhibits formation of Aβ fibrils and oligomers both in vitro and in mouse models of amyloid deposition. Here we studied the effect of CysC on cultured primary hippocampal neurons and a neuronal cell line exposed to either oligomeric or fibrillar cytotoxic forms of Aβ. The extracellular addition of the secreted human CysC together with preformed either oligomeric or fibrillar Aβ increased cell survival. While CysC inhibits Aβ aggregation, it does not dissolve preformed Aβ fibrils or oligomers. Thus, CysC has multiple protective effects in AD, by preventing the formation of the toxic forms of Aβ and by direct protection of neuronal cells from Aβ toxicity. Therapeutic manipulation of CysC levels, resulting in slightly higher concentrations than physiological could protect neuronal cells from cell death in Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: amyloid Aβ, cystatin C, Alzheimer's disease, neurodegeneration, neuroprotection

Introduction

The major neuropathological hallmarks of AD are senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuronal loss. Senile plaques comprise an extracellular core of aggregated, fibrillar Aβ accompanied by microglial cells, astrocytes, and dystrophic neuronal processes. Although Aβ is the major constituent of the amyloid deposits, minor components were identified, including CysC that has been reported to co-localize with Aβ in parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposits [1–4]. More recently, multiple studies have shown the genetic linkage of the CysC gene (CST3) with late-onset AD (for review see [5]). For an updated record of all published AD-associated studies for CST3 see the Alzgene Internet site of the Alzheimer Research Forum [6]. A synergistic risk association between the CST3 polymorphism and APOE ε4 alleles has been reported [7, 8]. Furthermore, in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that CysC binds to Aβ (Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42) and inhibits fibril formation and oligomerization of Aβ [9–12].

In addition to its anti-amyloidogenic role, CysC has a broad spectrum of biological roles in numerous cellular systems, with growth-promoting activity, inflammation down-regulating function, and anti-viral and anti-bacterial properties (for review see [5]). It is involved in numerous and varied processes such as cancer, renal diseases, diabetes, epilepsy and neurodegenerative diseases. Its function in the brain is unclear but it has been implicated in the processes of neuronal degeneration and repair of the nervous system (for review see [5]). In vitro studies that have used various cell types exposed to a variety of toxic stimuli have reached conflicting conclusions, as to whether CysC is protective or toxic to the cells.

Extensive research suggests that Aβ has an important role in the pathogenesis of neuronal dysfunction in AD (for reviews see [13–15]), although the pathologically relevant Aβ conformation remains unclear [16]. Aβ spontaneously aggregates into the fibrils that deposit in senile plaques. Synthetic Aβ peptides are toxic to hippocampal and cortical neurons, both in vitro and in vivo [17–19]. Aβ1–42 has been shown to induce protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation both in vitro and in vivo, and thus was suggested to play a central role as a mediator of free radical induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity in AD brains (for review see [20]). However, there is evidence that fibrillar Aβ may not be the most neurotoxic form of the peptide. The quantity and temporal progression of amyloid plaques do not show a simple relationship to the clinical progression of the disease [21]. Furthermore, extensive cortical plaques, mostly of the diffuse type, are present also in non-demented elderly [22]. Both in vitro and in vivo reports describe a potent neurotoxic activity for soluble, nonfibrillar, oligomeric assemblies of Aβ (for reviews see [23, 24]).

The primary structure of CysC is indicative of a secreted protein and accordingly, it has been demonstrated that most of the CysC is targeted extracellularly via the secretory pathway (for review see [5]). Therefore, we have studied the effect of exogenously applied human CysC on cells of neuronal origin under Aβ-induced neurotoxic stimuli, showing that CysC protects neuronal cells from death induced by both fibrillar and oligomeric Aβ. The data demonstrate that CysC has multiple neuroprotective functions, underscoring the importance of developing CysC-dependent therapy for AD.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

N2a cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown in Dulbeco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco Life Technologies-Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gemini Bio-products, West Sacramento, CA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% glutamine. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell cultures were washed twice with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (20 mM NaH2PO4, 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and once with warm serum-free medium prior to incubation in either serum-supplemented or serum-free medium. Either fibrillar or oligomeric pre-formed Aβ was added into serum-free medium in the absence or presence of human urinary CysC (Calbiochem- EMD Bioscience, San Diego, CA).

Primary cultures of hippocampal neurons

Primary cultures of hippocampal neurons were established from E18 pups of pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Labs, Wilmington, MA). Procedures involving experiments on animal subjects were done in accord with the provisions of the PHS “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and the “Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals”. Brains were harvested and maintained in sterile PBS, hippocampi were dissected out using a dissection microscope, triturated using a sterile glass Pasteur pipette and maintained in serum-free medium. Viable cells were counted using a hemacytometer. Neurons were plated in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B27 without antioxidants, 0.30% glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, at a density of 300,000 cells/ml in 24-well plates and 6-well plates coated with poly-D-lysine and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Neuronal cultures were treated 7 days post-plating.

Aβ preparation

Aβ1–42 peptide was purchased from Dr. David Teplow (California, UCLA) and was resuspended in 100% 1,1,1,3,3,3 hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) at a final concentration of 1 mM. For complete solubilization the peptide was homogenized using a Teflon plugged 250 μl Hamilton syringe. HFIP was removed by evaporation in a SpeedVac, Aβ1–42 resuspended at a concentration of 5 mM in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and sonicated for 10 minutes. Oligomers were prepared as previously described [25]: Aβ1–42 was diluted in PBS to 400 μM and 1/10 volume 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in H2O added. Aβ was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and further diluted to 100 μM in PBS followed by 18 hours incubation at 37°C. For generation of Aβ fibrils, the 5 mM DMSO Aβ1–42 solution was diluted in 10 mM HCl to make a 100 μM solution, vortexed for 30 seconds and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C as previously described [26].

N2a viability assay using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS)

20 μl of the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) were added into each well of the 96 wells plate containing cells in 100 μl culture medium, incubated with the reagent for 3 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2 and absorbance at 490 nm was recorded. As a negative control cell-free medium was included. Neuronal survival is expressed as percentage of neuronal survival in control cultures. Mean and SEM are calculated for 4 separate experiments and significance is calculated by Student's t-test.

Neuronal viability assay for hippocampal cultures

The number of viable cells was determined by quantifying the number of intact nuclei as described previously [27, 28]. Briefly, culture medium was removed by aspiration and 100 μl of detergent-containing lysis solution was added to the well. This solution dissolves cell membranes providing a suspension of intact nuclei. Intact nuclei were quantified using a hemacytometer. Triplicate wells were scored and are reported as mean ± SEM and significance is calculated by Student's t-test.

Western blot analysis

The proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto a 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman) in 2.5 mM Tris/19.2 mM Glycine/20% methanol transfer buffer. The membrane was blocked in Odyssey blocking buffer (Licor, Lincoln, NE) diluted 1:1 in PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, incubated with a monoclonal anti-caspase-2 antibody (1:1000; BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ) overnight at 4°C, and with secondary antibody (IRdye 800; 1:25,000; Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) for 2 hours at room temperature. The membrane was washed 3 times in PBST followed by a final wash in PBS. Bands were visualized and quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imager (Licor).

Dot blot analysis

Samples containing mixtures of Aβ and CysC were incubated in conditions in which Aβ forms oligomers as described above and blotted onto a 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The membrane was blocked in 5% milk (BioRad) in 10 mM Tris, 150 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.5, 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST), incubated with either anti-CysC antibody (Upstate, Temecula, CA) or A11 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 2 hours at room temperature, and with secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. The membrane was incubated in chemiluminiscent fluid (Millipore, Temecula, CA) for 60 seconds prior to exposure. The membrane was imaged using a Fuji LAS-3000 gel documentation unit for 10–60 seconds. Quantification was performed by digital image using the native Fuji software, ImageGauge. Mean and SEM are calculated for 4 separate experiments.

Biotin VADfmk isolation of active caspases

bVADfmk (biotin-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-fluoromethylketone) assay was used to detect the presence of active caspase-2. Rat hippocampal neurons were pre-treated for 2 hours with 50 μM bVADfmk (MP Biomedical, Solon, OH) at 37°C. Cells were treated for an additional 3 hours with 3 μM oligomeric Aβ and harvested in CHAPS buffer (150 mM KCl; 50 mM HEPES; 0.1% CHAPS; pH 7.4) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Complete Mini, Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Cells were spun at 15,000g for 10 minutes and the supernatant was collected and boiled for 5 minutes. Streptavidin agarose beads were added to the boiled supernatant and incubated in a rotor overnight at 4°C. Beads were spun at 7500g for 5 minutes, washed 5 times with PBS, resuspended in sample buffer (1% SDS, 3% Glycerol, and 20 mM Tris-Hcl, pH 6.8) and boiled 5 minutes. Beads in sample buffer were spun at 15,000g for 10 minutes, supernatant was collected and supplemented with 5% β-mercaptoethanol and samples loaded onto a 12% acrylamide-bis-acrylamide gel for Western blot analysis.

Results

CysC protects neuronal cells from Aβ-induced cell-death

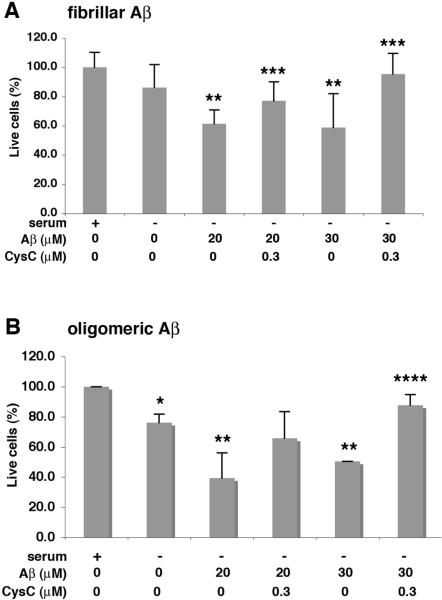

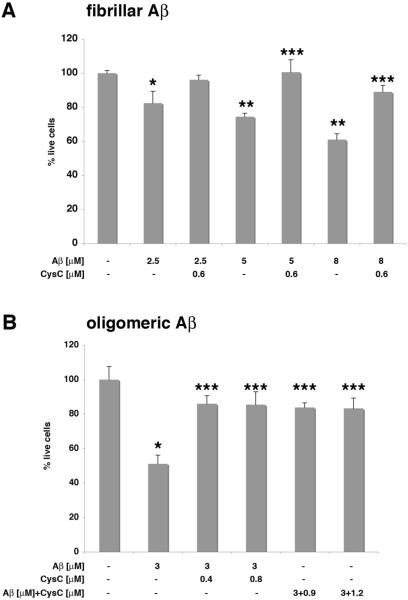

In vitro studies have demonstrated that CysC inhibits aggregation of Aβ into either fibrils [9] or oligomers [10] when incubated together under conditions that result in Aβ aggregation. Here we show that the addition of soluble CysC together with pre-aggregated Aβ directly protects N2a neuroblastoma cells from the toxicity induced by either fibrillar (Fig. 1A) or oligomeric (Fig. 1B) Aβ. Soluble CysC also protects rat primary hippocampal cells from Aβ-induced cell-death when cells were incubated in the presence of either fibrillar (Fig. 2A) or oligomeric (Fig. 2B) Aβ. In vitro studies have previously demonstrated that CysC does not dissolve pre-formed Aβ fibers or oligomers [9, 10]. Furthermore, we have found that under the incubation conditions used here CysC does not solublize aggregated Aβ. This suggests that CysC directly protects neuronal cells from Aβ-induced toxicity.

Figure 1. CysC protects N2a neuroblastoma cells from Aβ-induced cell-death.

N2a cells were incubated for 40–44 hours in serum-free medium, in the presence or absence of either fibrillar (A) or oligomeric (B) Aβ, in the presence or absence of human CysC. MTS analysis of live cells, presented as mean ± standard deviation of percent of live cells incubated in serum-containing medium without either Aβ or CysC (mean of 4 experiments; *p≤.02 and **p≤.003 for the difference from cells with serum; ***p≤.03 and ****p≤.002 for the difference from cells with Aβ without CysC).

Figure 2. CysC protects rat primary hippocampal neurons from Aβ-induced cell-death.

Cells were incubated for 24 hours, in the presence or absence of either fibrillar (A) or oligomeric (B) Aβ, in the presence or absence of human CysC. Additionally, Aβ was preincubated with CysC at conditions in which Aβ forms oligomers and the mix was added to the cells (B). Quantification of live cells, presented as mean ± standard deviation of percent of live cells incubated in serum-containing medium without either Aβ or CysC (mean of 4 experiments; *p≤.05 and **p≤.0003 for the difference from cells without Aβ and CysC; ***p≤.003 for the difference from cells with Aβ without CysC).

In vitro binding of CysC to Aβ inhibits Aβ oligomerization and prevents Aβ oligomers-induced cell death

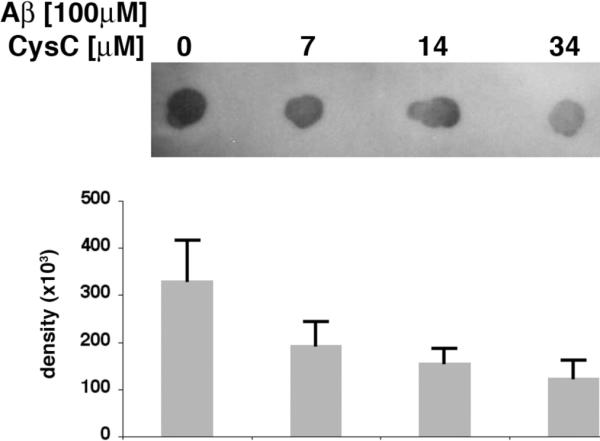

For analysis of the effect of CysC on Aβ oligomerization we prepared in vitro oligomeric Aβ1–42 from structurally homogeneous unaggregated starting material. Dot blot analysis with the conformation-dependent antibody A11 [29–32] demonstrated the formation of oligomers by Aβ1–42 in the absence of CysC (Fig. 3). When soluble Aβ1–42 was incubated under the same experimental conditions together with different concentrations of CysC, a CysC-concentration-dependent decrease in the oligomeric form of Aβ was observed (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. CysC inhibits Aβ oligomerization in vitro.

Dot blot analysis with the antibody specific for oligomeric conformation (A11) of Aβ42 (100 μM) incubated with CysC (0, 7, 14 or 34 μM). Mean ± standard deviation of quantification of the intensity of the blots from 3 experiments.

In order to test whether in vitro prevention of Aβ oligomerization decreases the toxicity of Aβ oligomers, the preincubated mixture of Aβ and CysC was added to rat primary hippocampal neurons. A significantly lower toxicity was observed as compared to the Aβ oligomers that were formed in the absence of CysC (Fig. 2B). Thus, prevention of Aβ oligomerization protects rat hippocampal neurons against Aβ-induced toxicity.

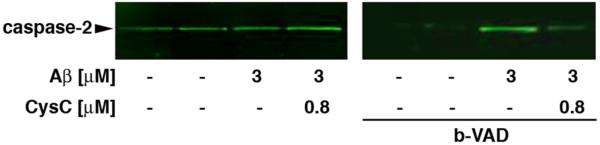

CysC prevents Aβ-induced caspase-2 activation

Rat primary hippocampal neurons were incubated in the presence or absence of oligomeric Aβ, in the presence or absence of CysC. In order to detect active caspase-2 we used an active site affinity ligand, bVADfmk. The biotinylated substrate irreversibly and covalently binds to the active cysteine site of most caspases in the cell trapping them in the activated form. Once bound to bVADfmk, the caspase is no longer active and downstream events are inhibited. Pre-treatment with bVADfmk, pull down of active caspases with streptavidin agarose beads followed by Western blot analysis with an antibody to caspase-2 revealed that while oligomeric Aβ induces caspase-2 activity, incubation of the cells with Aβ in the presence of CysC suppresses caspase-2 activity (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. CysC prevents Aβ-induced caspase-2 activation.

Rat primary hippocampal neurons were pre-treated for 2 hours with 50 μM bVADfmk. After 2 hours cells were incubated for an additional 3 hours in the presence or absence of 3 μM oligomeric Aβ and in the presence or absence of 0.8 μM CysC. Active caspase-2 was pulled down using streptavidin beads and identified by Western blot analysis with a monoclonal caspase-2 specific antibody. Representative blots are shown; the experiments were replicated 3 times.

Discussion

CysC is a secreted protein, targeted extracellularly via the secretory pathway and is taken up by cells (for review see [5]). Therefore, we have studied the in vitro effect of exogenously applied human CysC on cells of neuronal origin under neurotoxic stimuli. Here we show that CysC protects N2a neuroblastoma cells and rat primary hippocampal neurons from the toxicity induced by either oligomeric or fibrillar Aβ.

Aβ has been implicated in the pathophysiology of AD. The histopathological hallmarks of AD include the formation of Aβ amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, and the loss of synapses. While the temporal order in which these events occur and their relationship to one another is not clear, there is evidence of a direct toxic effect of Aβ on neurons [33]. Using different promoters a variety of transgenic models have been engineered to overexpress in the brain mutant forms of amyloid β precursor protein (AβPP). Several models reproducibly deposit Aβ and develop some of the prominent pathological and behavioral features of AD [34–40]. These findings resulted in focusing research on drugs that reduce the production of Aβ or enhance its degradation, and lowering cortical Aβ levels in some AD patients may be associated with stabilization of memory and cognitive decline [41, 42]. There are indications that both fibrillar Aβ and soluble oligomeric Aβ are neurotoxic [43–46]. However, Aβ has a widespread distribution through the brain and body and there is evidence that at physiological concentrations soluble Aβ serves a variety of physiological functions, including modulation of synaptic function, facilitation of neuronal growth and survival, protection against oxidative stress, and surveillance against neuroactive compounds, toxins and pathogens (for review see [47]). These physiological functions should be taken into account when strategies are developed to reduce Aβ load in AD, targeting oligomeric or fibrillar forms of Aβ, leaving monomeric soluble Aβ intact. Our approach does not reduce the level of soluble Aβ, focusing on enhanced binding of soluble Aβ to its carrier CysC, preventing its aggregation and fibril formation and enhancing CysC-mediated direct protection of neuronal cells from the toxicity induced by either form of Aβ.

Caspases are cysteine-dependent aspartate-specific proteases critically involved in apoptosis (for review see [48]). The detection of cleaved caspases and the accumulation of cleaved caspase substrates in brains of AD patients support the hypothesis that apoptosis may play a role in the subsequent neuronal loss found in AD brains [49, 50]. Elevated mRNA expression of several caspases was shown in the brain of AD patients compared with controls [51]. Pyramidal neurons from vulnerable regions involved in the disease showed an increase in activated caspases-3 and -6 [52, 53]. Synaptosomes prepared from AD brain frontal cortices showed an enrichment in caspase-9 compared with non-demented controls [54]. Studies have shown induction of apoptosis by Aβ in multiple neuronal cell types in culture [55–57]. Aβ-induced cell death was blocked by the broad spectrum caspase inhibitor N-benzyloxycarbonyl-val-ala-asp-fluoromethyl ketone and more specifically by the downregulation of caspase-2 with antisense oligonucleotides. In contrast, downregulation of caspase-1 or caspase-3 did not block Aβ-induced death [28]. Neurons from caspase-2- or 12-knockout mice are resistant to Aβ [28, 58]. The results indicate that caspase-2 is necessary for Aβ-induced apoptosis. Here we demonstrate that while Aβ induces activation of caspase-2 in primary hippocampal neurons, CysC inhibits this activation. This suggests that CysC protects neuronal cells from caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death induced by Aβ.

There are several indications that CysC has a role in AD: 1) Genetic studies have linked a CST3 polymorphism with an increased risk of developing AD (for review see [5, 6]). The amino acid exchange from Ala to Thr at the -2 position for signal peptidase cleavage [59], causes a less efficient cleavage of the signal peptide and thus a reduced secretion of CysC [60–62]. 2) Analysis of human cerebrospinal proteins by protein-chip array technology revealed that the combination of five polypeptides, including CysC, could be used for the diagnosis of AD and perhaps the assessment of its severity and progression [63]. 3) Recent findings that low serum CysC levels predict the development of AD in subjects free of dementia at baseline [64], suggest that low serum CysC levels precede clinical sporadic AD. 4) Immunohistochemical studies revealed strong dual staining with antibodies to Aβ and to CysC in a subpopulation of pyramidal neurons in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Co-localization of CysC with Aβ was found predominantly in amyloid-laden vascular walls, and in senile plaque cores of amyloid in the brains of AD, Down syndrome, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and cerebral infarction patients and non-demented aged individuals (for review see [5]). Co-localization of CysC with Aβ deposits was also found in brains of transgenic mice overexpressing human AβPP [4, 65]. 5) Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown that CysC binds to Aβ and inhibits fibril formation and oligomerization of Aβ in a concentration dependent manner [9, 10]. Such inhibitory effect was confirmed in vivo in Aβ-depositing transgenic AβPP mice over-expressing human CysC. A reduction in Aβ amyloid load was observed in the AβPP/CysC double transgenic mice compared to single AβPP transgenic mice [11, 12]. In vitro studies have shown that CysC inhibits the formation of high molecular weight Aβ oligomeric assemblies [10]. Moreover, the binding between Aβ and CysC in human CNS was detected in brains and in cerebrospinal of neuropathologically normal controls and in AD cases. The association of CysC with Aβ in brain from control individuals and in cerebrospinal reveals an interaction of these two polypeptides in their soluble form [66]. In addition to these previous data, showing that CysC prevents amyloid fibril formation and oligomerization of Aβ, the demonstration of direct protection of cells from the toxic forms of Aβ highlights the important defensive roles that CysC plays in AD.

Multiple studies have shown changes in CysC serum concentrations in a variety of conditions, including aging (for review see [67]). Enhanced CysC expression occurs in human patients with epilepsy and animal models of neurodegenerative conditions, in response to injury, including facial nerve axotomy, noxious input to the sensory spinal cord, perforant path transections, hypophysectomy, transient forebrain ischemia, and induction of epilepsy (for review see [5]). It has been suggested that this upregulation of CysC expression in response to injury and in various diseased conditions represents an intrinsic neuroprotective mechanism that may counteract progression of the disease. A reduction in CysC secretion is caused by the CST3 polymorphism in patients with late-onset sporadic AD and by two presenilin 2 mutations (PS2 M239I and T122R) linked to familial AD [68]. We propose that CysC is a carrier of soluble Aβ in body fluids such as cerebrospinal fluid and blood, as well as in the neuropil, where it plays an ongoing role in inhibiting the association of Aβ into insoluble plaques. Furthermore, CysC directly protects neuronal cells from Aβ-induced apoptotic cell death. The inhibition of Aβ aggregation caused by binding of CysC to Aβ and the direct protection of neuronal cells from Aβ-induced death suggest two mechanisms by which a reduced CysC brain concentration is associated with AD. These protective roles of CysC in the pathogenesis of AD suggest that a novel therapeutic approach that involves modulation of CysC levels may have important disease modifying effects.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by NIH grants AG017617 (EL) and NS043089 (CMT), and the Alzheimer's Association (IIRG0759699) (EL).

References

- [1].Maruyama K, Ikeda S, Ishihara T, Allsop D, Yanagisawa N. Immunohistochemical characterization of cerebrovascular amyloid in 46 autopsied cases using antibodies to β protein and cystatin C. Stroke. 1990;21:397–403. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vinters HV, Nishimura GS, Secor DL, Pardridge WM. Immunoreactive A4 and γ-trace peptide colocalization in amyloidotic arteriolar lesions in brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:233–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Itoh Y, Yamada M, Hayakawa M, Otomo E, Miyatake T. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a significant cause of cerebellar as well as lobar cerebral hemorrhage in the elderly. J Neurol Sci. 1993;116:135–141. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90317-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Levy E, Sastre M, Kumar A, Gallo G, Piccardo P, Ghetti B, Tagliavini F. Codeposition of cystatin C with amyloid-ß protein in the brain of Alzheimer's disease patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:94–104. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Levy E, Jaskolski M, Grubb A. The role of cystatin C in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and stroke: cell biology and animal models. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:60–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.tb00562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Gene overview of all published AD-association studies for CST3: http://www.alzforum.org/res/com/gen/alzgene/geneoverview.asp?geneid=66.

- [7].Beyer K, Lao JI, Gomez M, Riutort N, Latorre P, Mate JL, Ariza A. Alzheimer's disease and the cystatin C gene polymorphism: an association study. Neurosci Lett. 2001;315:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cathcart HM, Huang R, Lanham IS, Corder EH, Poduslo SE. Cystatin C as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64:755–757. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151980.42337.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sastre M, Calero M, Pawlik M, Mathews PM, Kumar A, Danilov V, Schmidt SD, Nixon RA, Frangione B, Levy E. Binding of cystatin C to Alzheimer's amyloid β inhibits amyloid fibril formation. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Selenica ML, Wang X, Ostergaard-Pedersen L, Westlind-Danielsson A, Grubb A. Cystatin C reduces the in vitro formation of soluble Aβ1–42 oligomers and protofibrils. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2007;67:179–190. doi: 10.1080/00365510601009738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mi W, Pawlik M, Sastre M, Jung SS, Radvinsky DS, Klein AM, Sommer J, Schmidt SD, Nixon RA, Mathews PM, Levy E. Cystatin C inhibits amyloid-β deposition in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1440–1442. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kaeser SA, Herzig MC, Coomaraswamy J, Kilger E, Selenica ML, Winkler DT, Staufenbiel M, Levy E, Grubb A, Jucker M. Cystatin C modulates cerebral β-amyloidosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1437–1439. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1991;6:487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stine WB, Jr., Dahlgren KN, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-β peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11612–11622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Geula C, Wu CK, Saroff D, Lorenzo A, Yuan M, Yankner BA. Aging renders the brain vulnerable to amyloid β-protein neurotoxicity. Nat Med. 1998;4:827–831. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lorenzo A, Yankner BA. β-amyloid neurotoxicity requires fibril formation and is inhibited by Congo red. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12243–12247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. In vitro aging of β-amyloid protein causes peptide aggregation and neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1991;563:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91553-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Butterfield DA, Boyd-Kimball D. Amyloid β-peptide(1–42) contributes to the oxidative stress and neurodegeneration found in Alzheimer disease brain. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:426–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Braak H, Braak E. Evolution of neuronal changes in the course of Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1998;53:127–140. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6467-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, Floriach-Robert M, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Dickson DW, Johnson KA, Petersen LE, McDonald WC, Braak H, Petersen RC. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Klein WL, Krafft GA, Finch CE. Targeting small Aβ oligomers: the solution to an Alzheimer's disease conundrum? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2004;44:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Barghorn S, Nimmrich V, Striebinger A, Krantz C, Keller P, Janson B, Bahr M, Schmidt M, Bitner RS, Harlan J, Barlow E, Ebert U, Hillen H. Globular amyloid -peptide oligomer - a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2005;95:834–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Jr., Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rukenstein A, Rydel RE, Greene LA. Multiple agents rescue PC12 cells from serum-free cell death by translation- and transcription-independent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 1991;11:2552–2563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-08-02552.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Troy CM, Rabacchi SA, Friedman WJ, Frappier TF, Brown K, Shelanski ML. Caspase-2 mediates neuronal cell death induced by β-amyloid. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1386–1392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01386.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bucciantini M, Giannoni E, Chiti F, Baroni F, Formigli L, Zurdo J, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM, Stefani M. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 2002;416:507–511. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kayed R, Sokolov Y, Edmonds B, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Hall JE, Glabe CG. Permeabilization of lipid bilayers is a common conformation-dependent activity of soluble amyloid oligomers in protein misfolding diseases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46363–46366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Demuro A, Mina E, Kayed R, Milton SC, Parker I, Glabe CG. Calcium dysregulation and membrane disruption as a ubiquitous neurotoxic mechanism of soluble amyloid oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17294–17300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yankner BA. Mechanisms of neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1996;16:921–932. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Games D, Adams D, Alessandrini R, Barbour R, Berthelette P, Blackwell C, Carr T, Clemens J, Donaldson T, Gillespie F, Guido T, Hagopian S, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Lee M, Leibovitz P, Lieburburg I, Little S, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Montoya-Zavala M, Mucke L, Paganini L, Penniman E, Power M, Schenk D, Seubert P, Snyder B, Soriano F, Tan H, Vitale J, Wadsworth S, Wolozin B, Zhao J. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1995;373:523–527. doi: 10.1038/373523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Masliah E, Sisk A, Mallory M, Mucke L, Schenk D, Games D. Comparison of neurodegenerative pathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosc. 1996;16:5795–5811. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05795.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Reaume AG, Howland DS, Trusko SP, Savage MJ, Lang DM, Greenberg BD, Siman R, Scott RW. Enhanced amyloidogenic processing of the β-amyloid precursor protein in gene-targeted mice bearing the Swedish familial Alzheimer's disease mutations and a “humanized” Aβ sequence. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23380–23388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Johnson-Wood K, Lee M, Motter R, Hu K, Gordon G, Barbour R, Khan K, Gordon M, Tan H, Games D, Lieberburg I, Schenk D, Seubert P, McConlogue L. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Aβ42 deposition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1550–1555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Moechars D, Dewachter I, Lorent K, Reverse D, Baekelandt V, Naidu A, Tesseur I, Spittaels K, Haute CV, Checler F, Godaux E, Cordell B, Van Leuven F. Early phenotypic changes in transgenic mice that overexpress different mutants of amyloid precursor protein in brain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6483–6492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sturchler-Pierrat C, Abramowski D, Duke M, Wiederhold KH, Mistl C, Rothacher S, Ledermann B, Burki K, Frey P, Paganetti PA, Waridel C, Calhoun ME, Jucker M, Probst A, Staufenbiel M, Sommer B. Two amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models with Alzheimer disease-like pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13287–13292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hock C, Konietzko U, Streffer JR, Tracy J, Signorell A, Muller-Tillmanns B, Lemke U, Henke K, Moritz E, Garcia E, Wollmer MA, Umbricht D, de Quervain DJ, Hofmann M, Maddalena A, Papassotiropoulos A, Nitsch RM. Antibodies against β-amyloid slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2003;38:547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nicoll JA, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, Weller RO. Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-β peptide: a case report. Nat Med. 2003;9:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nm840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kim HJ, Chae SC, Lee DK, Chromy B, Lee SC, Park YC, Klein WL, Krafft GA, Hong ST. Selective neuronal degeneration induced by soluble oligomeric amyloid β protein. Faseb J. 2003;17:118–120. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0987fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, Beach T, Kurth JH, Rydel RE, Rogers J. Soluble amyloid β peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW, Fuller SJ, Smith MJ, Beyreuther K, Bush AI, Masters CL. Soluble pool of Aβ amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:860–866. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::aid-ana8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang J, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. The levels of soluble versus insoluble brain Aβ distinguish Alzheimer's disease from normal and pathologic aging. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:328–337. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bishop GM, Robinson SR. Physiological roles of amyloid-β and implications for its removal in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:621–630. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200421100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ribe EM, Serrano-Saiz E, Akpan N, Troy CM. Mechanisms of neuronal death in disease: defining the models and the players. Biochem J. 2008;415:165–182. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cotman CW, Anderson AJ. A potential role for apoptosis in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 1995;10:19–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02740836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gervais FG, Xu D, Robertson GS, Vaillancourt JP, Zhu Y, Huang J, LeBlanc A, Smith D, Rigby M, Shearman MS, Clarke EE, Zheng H, Van der Ploeg LH, Ruffolo SC, Thornberry NA, Xanthoudakis S, Zamboni RJ, Roy S, Nicholson DW. Involvement of caspases in proteolytic cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid-β precursor protein and amyloidogenic Aβ peptide formation. Cell. 1999;97:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pompl PN, Yemul S, Xiang Z, Ho L, Haroutunian V, Purohit D, Mohs R, Pasinetti GM. Caspase gene expression in the brain as a function of the clinical progression of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:369–376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].LeBlanc A, Liu H, Goodyer C, Bergeron C, Hammond J. Caspase-6 role in apoptosis of human neurons, amyloidogenesis, and Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23426–23436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Stadelmann C, Deckwerth TL, Srinivasan A, Bancher C, Bruck W, Jellinger K, Lassmann H. Activation of caspase-3 in single neurons and autophagic granules of granulovacuolar degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Evidence for apoptotic cell death. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1459–1466. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65460-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lu DC, Rabizadeh S, Chandra S, Shayya RF, Ellerby LM, Ye X, Salvesen GS, Koo EH, Bredesen DE. A second cytotoxic proteolytic peptide derived from amyloid β-protein precursor. Nat Med. 2000;6:397–404. doi: 10.1038/74656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. Aggregation-related toxicity of synthetic β-amyloid protein in hippocampal cultures. Eur J Pharm. 1991;207:367–368. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Li YP, Bushnell AF, Lee CM, Perlmutter LS, Wong SK. β-amyloid induces apoptosis in human-derived neurotypic SH-SY5Y cells. Brain Res. 1996;738:196–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00733-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Estus S, Tucker HM, van Rooyen C, Wright S, Brigham EF, Wogulis M, Rydel RE. Aggregated amyloid-β protein induces cortical neuronal apoptosis and concomitant “apoptotic” pattern of gene induction. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7736–7745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07736.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, Li E, Xu J, Yankner BA, Yuan J. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-β. Nature. 2000;403:98–103. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Finckh U, von Der Kammer H, Velden J, Michel T, Andresen B, Deng A, Zhang J, Muller-Thomsen T, Zuchowski K, Menzer G, Mann U, Papassotiropoulos A, Heun R, Zurdel J, Holst F, Benussi L, Stoppe G, Reiss J, Miserez AR, Staehelin HB, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT, Binetti G, Hock C, Growdon JH, Nitsch RM. Genetic association of a cystatin C gene polymorphism with late-onset Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1579–1583. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.11.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Benussi L, Ghidoni R, Steinhoff T, Alberici A, Villa A, Mazzoli F, Nicosia F, Barbiero L, Broglio L, Feudatari E, Signorini S, Finckh U, Nitsch RM, Binetti G. Alzheimer disease-associated cystatin C variant undergoes impaired secretion. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;13:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(03)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Paraoan L, Ratnayaka A, Spiller DG, Hiscott P, White MR, Grierson I. Unexpected intracellular localization of the AMD-associated cystatin C variant. Traffic. 2004;5:884–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Noto D, Cefalu AB, Barbagallo CM, Pace A, Rizzo M, Marino G, Caldarella R, Castello A, Pernice V, Notarbartolo A, Averna MR. Cystatin C levels are decreased in acute myocardial infarction: effect of cystatin C G73A gene polymorphism on plasma levels. Int J Cardiol. 2005;101:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Carrette O, Demalte I, Scherl A, Yalkinoglu O, Corthals G, Burkhard P, Hochstrasser DF, Sanchez JC. A panel of cerebrospinal fluid potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Proteomics. 2003;3:1486–1494. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sundelof J, Arnlov J, Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Basu S, Zethelius B, Larsson A, Irizarry MC, Giedraitis V, Ronnemaa E, Degerman-Gunnarsson M, Hyman BT, Basun H, Kilander L, Lannfelt L. Serum cystatin C and the risk of Alzheimer disease in elderly men. Neurology. 2008;71:1072–1079. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326894.40353.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Steinhoff T, Moritz E, Wollmer MA, Mohajeri MH, Kins S, Nitsch RM. Increased cystatin C in astrocytes of transgenic mice expressing the K670N-M671L mutation of the amyloid precursor protein and deposition in brain amyloid plaques. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:647–654. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Mi W, Jung SS, Yu H, Schmidt SD, Nixon RA, Mathews PM, Tagliavini F, Levy E. Complexes of amyloid-β and cystatin C in the human central nervous system. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1147. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Madero M, Sarnak MJ, Stevens LA. Serum cystatin C as a marker of glomerular filtration rate. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:610–616. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000247505.71915.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Paterlini A, Missale C, Usardi A, Rossi R, Barbiero L, Spano P, Binetti G. Presenilin 2 mutations alter cystatin C trafficking in mouse primary neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]