Abstract

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are widespread environmental contaminants, and co-planar PCBs can induce oxidative stress and activation of pro-inflammatory signaling cascades which are associated with atherosclerosis. The majority of the toxicological effects elicited by co-planar PCB exposure are associated to activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and subsequent induction of responsive genes. Previous studies from our group have shown that quercetin, a nutritionally relevant flavonoid can significantly reduce PCB77 induction of oxidative stress and expression of the AHR responsive gene cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1). We also have evidence that membrane domains called caveolae may regulate PCB-induced inflammatory parameters. Thus, we hypothesized that quercetin can modulate PCB-induced endothelial inflammationassociated with caveolae. To test this hypothesis, endothelial cells were exposed to co-planar PCBs in combination with quercetin, and expression of pro-inflammatory genes was analyzed by real time PCR. Quercetin co-treatment significantly blocked both PCB77 and PCB126 induction of CYP1A1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), E-selectin and P-selectin. Exposure to PCB77 also induced caveolin-1 protein expression, which was reduced by cotreatment with quercetin. Our results suggest that inflammatory pathways induced by co-planar PCBs can be down-regulated by the dietary flavonoid quercetin through mechanisms associated with functional caveolae.

Keywords: Quercetin, PCBs, caveolae, AHR, CYP1A1, VCAM-1, MAPKs

Introduction

Environmental pollutants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons (HAHs), induce endothelial dysfunction and promote cardiovascular diseases (Hennig and others 2002b; Vogel and others 2004). The majority of the pro-inflammatory effects resulting from co-planar PCB exposure are mediated through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and AHR-dependent alterations in gene expression (Korashy and El-Kadi 2006; Matsumura 2003). Activation of AHR by co-planar PCBs and halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons (HAHs) results in induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and proinflammatory genes that play a critical role in atherosclerosis (Hennig and others 2002a; Puga and others 2000). We have demonstrated previously that exposure to AHR ligands can increase expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in endothelial cells(Hennig and others 2002b; Oesterling and others 2008; Slim and others 1999).

Recent studies have shown that, in addition to AHR activation, PCB toxicity requires functional lipid rafts called caveolae (Lim and others 2007; Oesterling and others 2008). Caveolae are cell surface invaginations of the plasma membrane that are highly enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids. They are characterized by the protein marker caveolin-1 (Frank and others 2003). Caveolin-1 is highly expressed in terminally differentiated cells including adipocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells. Caveolae and caveolin-1 are involved in regulating several signal transduction pathways that play a pathogenetic role in atherosclerosis(D’Alessio and others 2005; Frank and Lisanti 2004); and mice which lack the caveolin-1 gene appear to be protected against atherosclerosis (Frank and others 2004).

Flavonoids are polyphenolic compounds that are widely distributed in plants, fruits and vegetables and have been shown to be protective against pro-inflammatory stimuli (Arai and others 2000; Zheng and others 2008). Dietary flavonoids have a number of anti-inflammatory properties, including decreasing the expression of cell adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin (Choi and others 2004). The flavonol quercetin is one of the most abundant polyphenolic compounds found in the human diet and has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties (Stewart and others 2008).

Recent studies suggest that nutrition can alter the effects of exposure to environmental pollutants, including PCBs (Hennig and others 2005; Kozul and others 2008). Nutritional intervention using flavonoids and other bioactive nutrients may bioremediate the toxic effects associated with exposure to environmental pollutants (Hennig and others 2007). In the current study, we focused on quercetin, a major flavonoid in fruits and vegetables, and its anti-inflammatory effect was examined using primary pulmonary artery endothelial cells. The objective of this study was to determine if quercetin can alter PCB induction of proinflammtory pathways and early markers for atherosclerosis in vascular endothelial cells. Overall, our results provide evidence that quercetin can down-regulate PCB-induced inflammatory parameters and that regulatory mechanisms may involve functional caveolae.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

Primary endothelial cells were obtained from porcine pulmonary aortas and cultured as described previously (Toborek and others 2002). The basic culture medium consisted of M199 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT). The experimental media contained 1% FBS and were supplemented with quercetin (3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and/or co-planar PCBs, such as PCB77 (3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl) or PCB126 (3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl). PCB77 was a generous gift from Dr. Larry W. Robertson, University of Iowa, and PCB126 was purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT). PCB77 was solubilized in DMSO (sterile-filtered, Sigma-Aldrich, MO) and the final concentration of DMSO in the culture media did not exceed 0.03%. Quercetin is a flavonoid commonly found in fruits and vegetables. Quercetin is an example of flavonoids that are quite efficiently absorbed and that provide kinetics of significant plasma concentrations of parent compounds (and metabolites) that can be achieved during repeated dietary intake of fruits and vegetables (Manach and others 2005).

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed using whole cell extracts as previously described (Lim and others 2007). Briefly, cell lysates containing equal amounts of total protein were fractionated by electrophoresis on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Non-specific binding was blocked by soaking the membrane in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) and 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody [anti-CYP1A1 and anti-AHR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), anti-Cav-1 and anti-phospho-Cav-1 antibodies (Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO), and anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma Chemical Co.)]. After three washes with TBST, the membrane was then incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The protein levels were determined using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare UK Ltd., England) and blue autoradiography film (ISC BioExpress, Kaysville, UT).

Real-time PCR

Endothelial cells were pre-treated with10 μM quercetin for 30 min followed by treatment with 2.5 μM PCB77 for 6 h. Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). cDNA sequences for target genes were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health), and primers for real time PCR were designed using Primer Express 3.0 software for real time PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The following primers were employed; CYP1A1 forward 5′ GGC CAC CTG GGA ACT GAT G 3′, reverse: 5′CCC CTA ATG CTC CTA ACC TCC TA 3′, VCAM-1 forward: 5′ TGG AAA GAC ATG GCT GCC TAT 3′, reverse: 5′ACA CCA CCC CAG TCA CCA TAT C 3′, E-selectin forward: 5′ CAA TGG TAC ATG GAC ATG GAT AGG 3′, reverse: 5′ CAG TCC TCG TTG CTT TGC TTA TT 3′, P-selectin forward: 5′ TCA CAG ACT TAG TGG CCA TCC A 3′, reverse: 5′ ATC TTT CGC ATC CCA ATC CA 3′, and β-actin forward: 5′ TCA TCA CCA TCG GCA ACG 3′, reverse: 5′ TTC CTG ATG TCC ACG TCG 3′. Real time PCR was performed on a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and using Sybr Green (Applied Biosystems) for target gene detection according to manufacturer instructions. The expression values of target genes were normalized correspondingly to β-actin, which was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between treatments were made by Students t-test or two-wayanalysis of variance followed by Tukey’s pairwise multiple comparison procedure using SigmaStat 2.0 software (Jandel Corp., San Rafael, CA). Statistical probability of P< 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

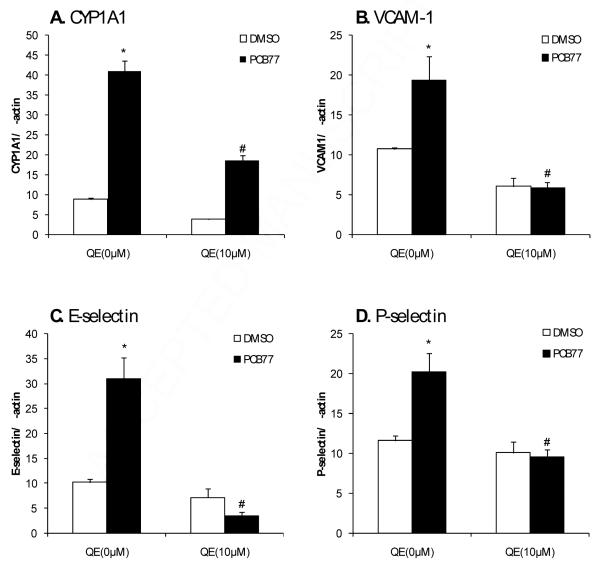

Quercetin blocks PCB77-mediated induction of CYP1A1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and P-selectin mRNAs

To determine the effects of quercetin on PCB-mediated induction of cell adhesion molecules, endothelial cells were treated with 10 μM quercetin and/or PCB77. Quercetin significantly blocked PCB77 induction of CYP1A1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and P-selectin mRNA expression (Figures 1A - D). These results suggest that quercetin is protective against PCB77 induction of pro-inflammatory genes in endothelial cells.

Figure 1.

Quercetin (QE) alters PCB77-induced expression of AHR responsive and pro-inflammatory genes. Endothelial cells were grown to confluency and then pre-treated with 10 μM quercetin for 30 min followed by co-treatment with vehicle (DMSO) or 2.5 μM PCB77 for 6 h. RNA was extracted and real time PCR was conducted to measure expression of CYP1A1 (A), VCAM-1 (B), E-selectin (C) and P-selectin (D). Bars represent average ± SEM, n=5; *significantly higher than control cultures; # significantly lower than cells treated with PCB alone.

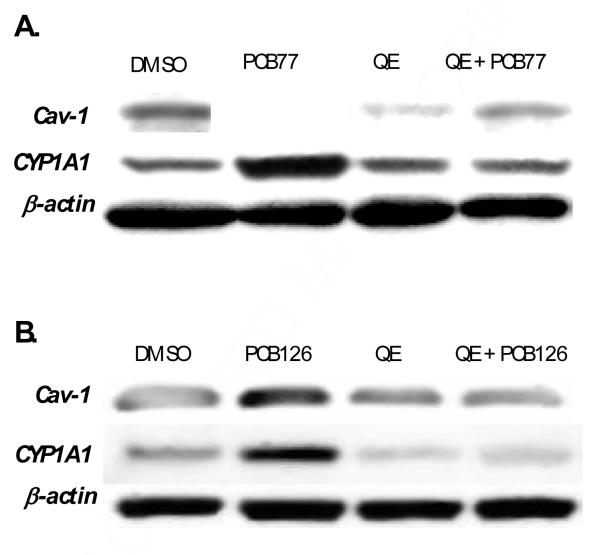

Quercetin blocks PCB77-mediated induction of caveolin-1 protein expression and caveolin-1 phosphorylation status

Our previous studies suggest that caveolae and its structural protein caveolin-1 may play a critical role in mediating AHR ligand-induced inflammation (Lim and others 2007; Oesterling and others 2008). To determine if quercetin can reduce caveolin-1-mediated events, endothelial cells were treated with 10 μM quercetin and/or 2.5 μM PCB77. Expression of CYP1A1, caveolin-1 and β-actin protein expression was measured by Western blots. Treatment with quercetin significantly blocked PCB77-mediated induction of CYP1A1 and caveolin-1 protein expression (Fig.2A). Similar results were obtained when treating cells with PCB126 and quercetin (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Quercetin (QE) blocks PCB77 and PCB126 induction of caveolin-1 (Cav-1) and CYP1A1 protein expression (A and B). Endothelial cells were grown to confluency and then pre-treated with 10 μM QE for 30 min followed by co-treatment with vehicle (DMSO) or with 2.5 μM PCB77 or PCB126 for 6 h. Total cellular protein was isolated and target proteins were analyzed by Western blot.

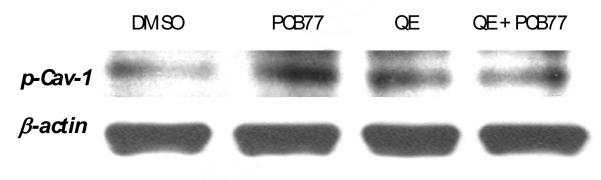

Phosphorylation of caveolin-1 is an early event in caveolae-dependent activation of pro-inflammatory cell signaling cascades (Hua and others 2003) and is also necessary for caveolae endocytosis (Salanueva and others 2007). To determine if quercetin can down-regulate PCB77-induced alterations in caveolin-1 phosphorylation status, endothelial cells were pre-treated with quercetin followed by co-treatment with PCB77. The phosphorylation status of caveolin-1 was measured by Western blot. Our results suggest that PCB77 can increase caveolin-1 phosphorylation and that pre-treatment with quercetin can reduce this effect (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Quercetin (QE) blocks PCB77-induced phosphorylation of caveolin-1 (p-Cav-1). Cells were grown to confluency and then pre-treated with 10 μM QE for 30 min followed by co-treatment with vehicle (DMSO) or 2.5 μM PCB77 for 5 min. Total cellular protein was isolated and target proteins were analyzed by Western blot.

Discussion

Overall, the results from this study suggest that quercetin, a bioactive flavonoid present in various fruits and vegetables, is protective against PCB-induced inflammation in vascular endothelial cells. Endothelial cells treated with quercetin were resistant to PCB77 induction of CYP1A1, VCAM-1, E-selectin, and P-selectin mRNA, Cav-1 protein, and caveolin-1 phosphorylation.

The observed effects of quercetin pre-treatment on PCB77 induction of CYP1A1 and cell adhesion molecules suggest that this flavonoid can block endothelial cell damage and activation associated with inflammation. Previous studies from our laboratory and others have shown that quercetin can block co-planar PCB and HAH induction of CYP1A1 expression and activity (Ramadass and others 2003; Zhang and others 2003). We also have demonstrated previously that treatment with quercetin prevent the observed increase in production of ROS by PCB77 (Ramadass and others 2003). These studies suggest that quercetin is protective against PCB77-induced ROS production by interfering with AHR activation and induction or pro-oxidative enzymes such as CYP1A1.

Quercetin-dependent inhibition of cell adhesion molecule VCAM-1, E-selectin and P-selectin induction by PCB77 suggests that quercetin can protect against PCB-induced vascular inflammation. Increased expression of VCAM-1, E-selectin and P-selectin are commonly observed in early atherosclerotic lesions. Specifically, E and P-selectin play an important role in recruitment and activation of immune cells to sites of vascular injury. The expression of VCAM-1 and E-selectin is increased by activation of pro-inflammatory cell signaling cascades such as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) (Blankenberg and others 2003; Collins and Cybulsky 2001). We have shown previously that exposure to co-planar PCBs can increase transcriptional activity of NF-κB in endothelial cells (Hennig and others 2002b; Slim and others 1999). The gene expression results reported in this study suggest that quercetin can interfere with NF-κB-dependent regulation of vascular adhesion molecule expression.

In addition to blocking activation of the AHR pathway, the inhibition by quercetin of PCB77-induced expression and phosphorylation of caveolin-1 represents a novel mechanism for quercetin-dependent protection against this pro-inflammatory environmental pollutant. In addition to PCB77, induction of caveolin-1 and CYP1A1 by PCB126 can also be blocked by quercetin. The mechanism of protective properties of quercetin are not clear but may be sensitive to intracellular oxidative stress. For example, quercetin has been shown to block hydrogen peroxide dependent induction of caveolin-1 (Dasari and others 2006; Kook and others 2008). Caveolae and its structural component caveolin-1 are known to mediate vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis (Frank and Lisanti 2004; Frank and others 2003). Studies using various in vivo models have shown that caveolin-1 is necessary for the induction of pro-inflammatory markers and the development of atherosclerosis (Frank and others 2004; Garrean and others 2006). Interestingly, the expression, cellular localization and function of cell adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and E-selectin are dependent on caveolae integrity (Kiely and others 2003; Millan and others 2006; Shin and others 2006). Recent findings from our laboratory also suggest that caveolin-1 expression and function plays a critical role in coplanar PCB or HAH-induced activation of pro-inflammatory cell signaling cascades and induction of cell adhesion molecules (Lim and others 2007; Oesterling and others 2008). In summary, our findings in combination with the results reported from this study suggest that PCB-induced caveolin-1 expression is necessary for the activation of endothelial cells and that quercetin may protect against these effects by interfering with caveolin-1 induction and AHR-associated gene expression.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from NIEHS, NIH (P42ES07380, R25ES016248), the University of Kentucky AES, the University of Kentucky Lyman T. Johnson Postdoctoral Fellowship and the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2007-357-F00045). PCB77 was a generous gift from Dr. Larry Robertson (University of Iowa Superfund Basic Research Program).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arai Y, Watanabe S, Kimira M, Shimoi K, Mochizuki R, Kinae N. Dietary intakes of flavonols, flavones and isoflavones by Japanese women and the inverse correlation between quercetin intake and plasma LDL cholesterol concentration. J Nutr. 2000;130:2243–2250. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.9.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg S, Barbaux S, Tiret L. Adhesion molecules and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Choi YJ, Park SH, Kang JS, Kang YH. Flavones mitigate tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced adhesion molecule upregulation in cultured human endothelial cells: role of nuclear factor-kappa B. J Nutr. 2004;134:1013–1019. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.5.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins T, Cybulsky MI. NF-kappaB: pivotal mediator or innocent bystander in atherogenesis? J Clin Invest. 2001;107:255–264. doi: 10.1172/JCI10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessio A, Al-Lamki RS, Bradley JR, Pober JS. Caveolae participate in tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling and internalization in a human endothelial cell line. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasari A, Bartholomew JN, Volonte D, Galbiati F. Oxidative stress induces premature senescence by stimulating caveolin-1 gene transcription through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/Sp1-mediated activation of two GC-rich promoter elements. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10805–10814. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank PG, Lee H, Park DS, Tandon NN, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP. Genetic ablation of caveolin-1 confers protection against atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:98–105. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000101182.89118.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank PG, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 and caveolae in atherosclerosis: differential roles in fatty streak formation and neointimal hyperplasia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004;15:523–529. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200410000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank PG, Woodman SE, Park DS, Lisanti MP. Caveolin, caveolae, and endothelial cell function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1161–1168. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000070546.16946.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrean S, Gao XP, Brovkovych V, Shimizu J, Zhao YY, Vogel SM, et al. Caveolin-1 regulates NF-kappaB activation and lung inflammatory response to sepsis induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2006;177:4853–4860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig B, Ettinger AS, Jandacek RJ, Koo S, McClain C, Seifried H, et al. Using nutrition for intervention and prevention against environmental chemical toxicity and associated diseases. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:493–495. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig B, Hammock BD, Slim R, Toborek M, Saraswathi V, Robertson LW. PCB-induced oxidative stress in endothelial cells: modulation by nutrients. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2002a;205:95–102. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig B, Meerarani P, Slim R, Toborek M, Daugherty A, Silverstone AE, et al. Proinflammatory properties of coplanar PCBs: in vitro and in vivo evidence. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002b;181:174–183. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig B, Reiterer G, Toborek M, Matveev SV, Daugherty A, Smart E, et al. Dietary fat interacts with PCBs to induce changes in lipid metabolism in mice deficient in low-density lipoprotein receptor. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:83–87. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua H, Munk S, Whiteside CI. Endothelin-1 activates mesangial cell ERK1/2 via EGF-receptor transactivation and caveolin-1 interaction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F303–312. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00127.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely JM, Hu Y, Garcia-Cardena G, Gimbrone MA., Jr. Lipid raft localization of cell surface E-selectin is required for ligation-induced activation of phospholipase C gamma. J Immunol. 2003;171:3216–3224. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kook D, Wolf AH, Yu AL, Neubauer AS, Priglinger SG, Kampik A, et al. The protective effect of quercetin against oxidative stress in the human RPE in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1712–1720. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korashy HM, El-Kadi AO. The role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the pathogenesis cardiovascular diseases. Drug Metab Rev. 2006;38:411–450. doi: 10.1080/03602530600632063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozul CD, Nomikos AP, Hampton TH, Warnke LA, Gosse JA, Davey JC, et al. Laboratory Diet Profoundly Alters Gene Expression and Confounds Genomic Analysis in Mouse Liver and Lung. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.02.008. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim EJ, Smart EJ, Toborek M, Hennig B. The role of caveolin-1 in PCB77-induced eNOS phosphorylation in human-derived endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3340–3347. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00921.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manach C, Williamson G, Morand C, Scalbert A, Remesy C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:230S–242S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.230S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura F. On the significance of the role of cellular stress response reactions in the toxic actions of dioxin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan J, Hewlett L, Glyn M, Toomre D, Clark P, Ridley AJ. Lymphocyte transcellular migration occurs through recruitment of endothelial ICAM-1 to caveola- and F-actin-rich domains. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:113–123. doi: 10.1038/ncb1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterling E, Toborek M, Hennig B. Benzo[a]pyrene induces intercellular adhesion molecule-1 through a caveolae and aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediated pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puga A, Barnes SJ, Chang C, Zhu H, Nephew KP, Khan SA, et al. Activation of transcription factors activator protein-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:997–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00406-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadass P, Meerarani P, Toborek M, Robertson LW, Hennig B. Dietary flavonoids modulate PCB-induced oxidative stress, CYP1A1 induction, and AhR-DNA binding activity in vascular endothelial cells. Toxicol Sci. 2003;76:212–219. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanueva IJ, Cerezo A, Guadamillas MC, del Pozo MA. Integrin regulation of caveolin function. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:969–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Kim J, Ryu B, Chi SG, Park H. Caveolin-1 is associated with VCAM-1 dependent adhesion of gastric cancer cells to endothelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2006;17:211–220. doi: 10.1159/000094126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slim R, Toborek M, Robertson LW, Hennig B. Antioxidant protection against PCB-mediated endothelial cell activation. Toxicol Sci. 1999;52:232–239. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/52.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LK, Soileau JL, Ribnicky D, Wang ZQ, Raskin I, Poulev A, et al. Quercetin transiently increases energy expenditure but persistently decreases circulating markers of inflammation in C57BL/6J mice fed a high-fat diet. Metabolism. 2008;57:S39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toborek M, Lee YW, Kaiser S, Hennig B. Measurement of inflammatory properties of fatty acids in human endothelial cells. Methods Enzymol. 2002;352:198–219. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)52020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel CF, Sciullo E, Matsumura F. Activation of inflammatory mediators and potential role of ah-receptor ligands in foam cell formation. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2004;4:363–373. doi: 10.1385/ct:4:4:363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Qin C, Safe SH. Flavonoids as aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists/antagonists: effects of structure and cell context. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1877–1882. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Lim EJ, Wang L, Smart EJ, Toborek M, Hennig B. Role of caveolin-1 in EGCG-mediated protection against linoleic-acid-induced endothelial cell activation. J Nutr Biochem. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]