Abstract

Purpose

To determine if adjusting for blood vessel location can decrease the inter-subject variability of retinal nerve fiber (RNFL) thickness measured with optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Subjects and Methods

One eye of 50 individuals with normal vision was tested with OCT and scanning laser polarimetry (SLP). The SLP and OCT RNFL thickness profiles were determined for a peripapillary circle 3.4 mm in diameter. The midpoints between the superior temporal vein and artery (STva) and the inferior temporal vein and artery (ITva) were determined at the location where the vessels cross the 3.4 mm circle. The average OCT and SLP RNFL thicknesses for quadrants and arcuate sectors of the lower and upper optic disc were obtained before and after adjusting for blood vessel location. This adjustment was done by shifting the RNFL profiles based upon the locations of the STva and ITva relative to the mean locations of all 50 individuals.

Results

Blood vessel locations ranged over 39° (STva) and 33° (ITva) for the 50 eyes. The location of the leading edge of the OCT and SLP profiles was correlated with the location of the blood vessels for both the superior [r=0.72 (OCT) and 0.72(SLP)] and inferior [r=0.34 and 0.43] temporal vessels. However, the variability in the OCT and SLP thickness measurements showed little change due to shifting. After shifting, the difference in the coefficient of variation ranged from −2.1% (shifted less variable) to +1.7% (unshifted less variable).

Conclusion

The shape of the OCT and SLP RNFL profiles varied systematically with the location of the superior and inferior superior veins and arteries. However, adjusting for the location of these major temporal blood vessels did not decrease the variability for measures of OCT or SLP RNFL thickness.

Keywords: glaucoma, optical coherence tomography, blood vessels

In glaucoma, retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning results from progressive loss of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons. It is now possible to obtain in vivo measurements of the RNFL thickness. For example, optical coherence tomography (OCT) uses light and interferometry to determine the depth of surfaces differing in reflectance much in the way sonar or ultrasound uses sound.1–4 The commonly used time domain OCT technique measures RNFL thickness along a circular path around the optic disc. Various measures of the resulting RNFL thickness profile can be compared to normative data to determine whether the RNFL is abnormally thin.

Measures based upon OCT RNFL thickness generally show good sensitivity and specificity for detecting glaucomatous damage.5–19 However, there is considerable inter-subject variation in the RNFL thickness profiles, even among normal controls. For example, although the RNFL profiles from the two eyes of an individual are very similar,20,21 the profiles differed markedly in both amplitude and waveform across individuals.22 If inter-individual variability can be reduced, it should be possible to improve the sensitivity and specificity of tests based upon OCT RNFL thickness.

Recent evidence suggests that the location of the superior and inferior temporal blood vessels (BVs) may account for a portion of the inter-subject variability.22 In particular, the location of the major peaks in the RFNL profiles coincide with the approximate location of the superior and inferior temporal BVs. In part, this is due to the direct contribution of these BVs to RNFL thickness as measured by OCT22–24 and, in part, due to the correlation between the location of these BVs and the location of the arcuate bundles.23 We have previously suggested that adjusting for the location of these BVs might decrease variability among controls.22 In the present study, we tested this hypothesis by adjusting RNFL profiles based upon the position of the superior and inferior temporal BVs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

One eye of each of 50 consecutive healthy individuals, mean age 45.1 ± 12.1 yrs, was assessed with OCT, scanning laser polarimetry (SLP) and static automated perimetry. All individuals underwent a complete eye examination, including slit-lamp biomicroscopy, best-corrected visual acuity, gonioscopy, IOP measurements with Goldmann applanation tonometry, stereoscopic ophthalmoscopy of the optic disc with a 78-D lens, stereoscopic disc photos, and static automated perimetry. The eyes had intraocular pressure (IOP) ≤21 mmHg, a healthy appearing optic disc, no history of ocular disease, and reliable (less than 33% fixation losses, false positive and negative responses) normal visual fields (SITA, program 24–2; Humphrey Field Analyzer II, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, California). A normal visual field was defined as one with a mean deviation (MD) or a pattern standard deviation (PSD) within the 95% confidence interval and a normal Glaucoma Hemifield Test (GHT).

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before their participation. Procedures followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Board of Research Associates of Columbia University and by the Institutional Review Board of the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary.

Imaging

RNFL thickness was measured using OCT and a fast RNFL circular scan protocol (Stratus OCT3, Zeiss Meditech, Dublin, CA) and scanning laser polarimetry (SLP) (GDx-VCC, Zeiss Meditech, Dublin, CA). Pupils were dilated for the OCT, but not the SLP measurements. The OCT circular scan data consisted of the average of 3 circular scans (3.4 mm in diameter) per set and sets with a signal less than 6 were not used. The RNFL thickness profiles were exported (256 points). Figure 1A contains an example of an OCT RNFL thickness profile from one of the eyes.

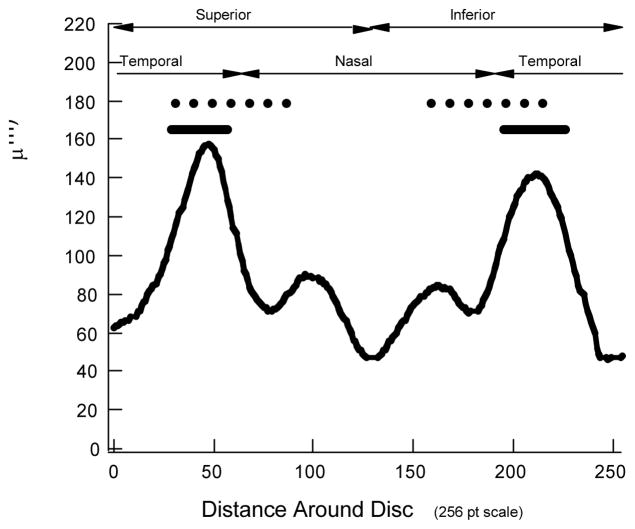

FIGURE 1.

A. An OCT RNFL thickness profile from a healthy eye. B. Example of a SLP density plot used to export data for SLP analysis. C. SLP RNFL profile obtained around green ring in panel B. D. A fundus image from the SLP report used to identify the location of the major temporal vein and artery in the superior (STva) and inferior (ITva) disc regions. The red and blue lines show the location of STva and ITva and the black arcs show the range of locations for the individuals in this study.

For the SLP analysis, data were exported from the density plot available in the commercial SLP report (see Fig. 1B). Scans with quality scores <8 were excluded. There were two reasons for exporting these data as opposed to the 64-point RNFL profile supplied in the commercial SLP report. First, these data allowed us to measure the points around a circle of the same diameter (3.4 mm) used in the OCT3 measurements. Second, the SLP RNFL profile reported by the machine’s software is derived from the density map via an algorithm based upon the assumption that the BVs are largely hiding, as opposed to displacing, the axons. A more accurate picture of the contributions of axons, as opposed to BVs, can be obtained by taking the SLP readings at face value. In particular, our analysis circle, green circle in Fig. 1B, had a radius of 3.4 mm and a thickness of 8 pixels (0.37 mm), the same thickness used by the SLP machine to report the RNFL profile. The result, shown for one eye in Fig. 1C as the solid curve, is a series of peaks and depressions with the depressions corresponding to the location of the BVs.

All further analyses were performed using the OCT RNFL profile (Fig. 1A) and the raw SLP density data (solid black curve in Fig. 1C).

Measuring the location of the major temporal veins and arteries

Our focus here is on the major peaks of the OCT RNFL profiles, which are associated with the arcuate regions of the visual field and the location of the superior and inferior temporal retinal arteries and veins. Figure 1D shows a fundus image from the commercial SLP report. The midpoint between the major temporal vein and artery in the superior (STva) and inferior (ITva) disc regions, as they cross the circle with a 3.4 mm diameter, was marked on the fundus image as shown in Fig. 1D by the blue and red lines. The location of these midpoints was converted to a 256 point scale and to degrees, where 0 degrees is the temporal most (9 o’clock position for right eye) location. The blue and red dashed lines in Fig. 1A,C show the location of the midpoints of the BVs for this individual.

Measuring the thickness of the arcuate regions of RNFL profiles

The RNFL thickness of the portions of the OCT and SLP superior and inferior temporal regions was determined before and after adjusting for the location of the STva and ITva. For this analysis, 2 superior and 2 inferior temporal disc regions were defined. In particular, we used the superior and inferior quadrants as defined by the OCT commercial report (dashed line in Fig. 2) and the superior and inferior temporal sectors as defined by the Garway-Heath et al25 map. The disc locations of the Garway-Heath et al arcuate sectors are shown by the black solid bars in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

The black dashed and solid horizontal lines indicate the regions included within the quadrant and Garway-Heath et al(G-H) sectors, respectively. The curves represent the average OCT RNFL profiles for all 50 eyes.

For all individuals, the average OCT and SLP RNFL thicknesses for these sectors of the lower and upper optic disc were obtained before and after shifting for relative STva and ITva locations. To determine the relative location of STva and ITva, the average locations were first determined for all 50 eyes. The relative locations of STva and ITva were determined for each of the individual eyes by subtracting the average values from the values for that individual. For the shifted data, the boundaries were moved based upon these relative locations with the superior disc regions adjusted by the relative position of the STva and the inferior disc regions by the relative position of the ITva.

RESULTS

Variation in the location of superior and inferior temporal BVs

As expected, there was considerable variation in the location of the major temporal BVs.22 For the 50 eyes, the location of the midpoint of the superior temporal vein and artery (STva) ranged over 39° and the inferior temporal vein and artery (ITva) ranged over 33°. The black arcs in Fig. 1D show these ranges. The mean locations of STva and ITva were 76.2±9.4° and 279±8.5°, respectively. In addition, there was a weak correlation (r=0.21) between the locations of the STva and ITva.

OCT RNFL profiles and BV location

Figure 3A contains the OCT RNFL profiles for all 50 of the eyes, with the bold black curve showing the mean of the profiles. As expected the shape of the RNFL profiles for healthy eyes show considerable variation.20 The vertical dashed lines are the mean locations for the STva and ITva for all 50 eyes. The horizontal solid lines at the bottom of the vertical lines show the range of STva and ITva locations.

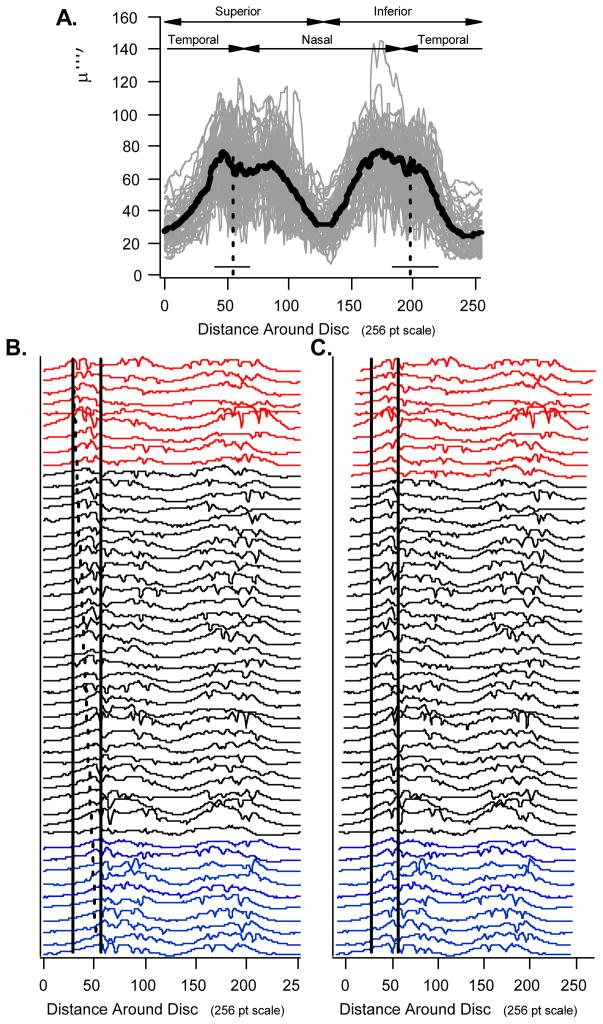

FIGURE 3.

A. The OCT RNFL profiles for all 50 individuals with the mean of these profiles shown in bold. The vertical dashed lines are the mean locations for the STva and ITva and the horizontal solid lines the range. B. The profiles from panel A positioned from top to bottom in order of the location of the STva. C. The same profiles as in panel B, but shifted by an amount equal to the relative locations of the STva.

Figure 3B shows the 50 OCT profiles from Fig. 3A positioned from top to bottom in order of the location of the STva; the top profiles are associated with the more temporal location of the STva. The solid vertical lines mark the boundaries of the superior temporal Garway-Heath et al sector (solid black bars in Fig. 2). Notice that as you move down the display, the first peak of the profiles moves from just inside the left (temporal) boundary to just on the right (nasal) boundary. The angled dashed line connects the first peaks of top and bottom profiles.

To obtain a better picture of this relationship between RNFL profile and STva location, two groups of RNFL profiles were formed consisting of the 10 associated with the most temporal location of the STva (red in Fig. 3B) and the 10 associated with the most nasal location of the STva (blue in Fig. 3B). The averages of these profiles are shown as the red (most temporal STva) and blue (most nasal STva) curves in Fig. 4A along with the mean locations (dashed vertical lines) of the STva for these individuals. Note that the profiles in the superior disc for the most extreme BV locations appear shifted relative to each other. This shift is in the same direction, and about the same magnitude, as the shift in the locations of the STva. To see this relationship more clearly, Fig. 3C shows the same profiles as in Fig. 3B, but in this case each is shifted by an amount equal to the relative locations of the STva. The first peaks are more in line after shifting for BV location than before (Fig. 3B). Figure 4B shows the results for an analogous analysis for the ITva and the inferior disc region. The trends are the same.

FIGURE 4.

A. The averages of the OCT RNFL profiles in Fig. 3B with the most temporal STva (red) and most nasal STva (blue) along with the mean locations (vertical lines) of the STva for these individuals. B. Same as in panel A, but for an analogous analysis for the ITva and the inferior disc region. C. Same as in panel A, but for the SLP profiles in Fig. 5B. D. Same as in panel C, but for an analogous analysis for the ITva and the inferior disc region.

SLP RNFL profiles and BV location

Given that the BVs contribute to the thickness of the OCT RNFL profiles, the results above could, at least in part, be explained by the BV contribution. The SLP RNFL profiles, in principle, should contain little or no contribution from the BVs per se. Figure 5, in the same format as Fig. 3, indicates that the SLP results follow a similar pattern. First, there is considerable variation in the RNFL profiles (Fig. 5A). Second, the first peak (local maximum) of the individual profiles systematically shifts from the temporal boundary of the G-H sector (left vertical line in Fig. 5B) to the nasal boundary (right vertical line) when the profiles are ordered in terms of the location of the STva as in Fig. 5B. Third, shifting each profile by the relative position of the STva, in general, brings the first local maxima more in line (Fig. 5C). Fourth, the average of the 10 profiles with the most extreme temporal position of the STva (red curve in Fig. 4C) appears shifted relative to the average profile for the most extreme nasal position (blue curve in Fig. 4C). Finally, similar results are seen for the analysis of the ITva (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 5.

A. The SLP RNFL profiles for all 50 eyes with the mean of these profiles shown in bold. The vertical dashed lines are the mean locations for the STva and ITva and the horizontal solid lines the range. B. The profiles from panel A positioned from top to bottom in order of the location of the STva. C. The same profiles as in panel B, but shifted by an amount equal to the relative locations of the STva.

BV location and the temporal edge of the RNFL profile

To examine the relationship between the location of the arcuate bundles and the major temporal BVs, the location of the midpoint of the temporal edges of the OCT RNFL profile were determined as indicated in Fig. 6A. (Note: the midpoint of the edge was used as a proxy for the relative location of the arcuate bundle as it is less dependent upon the BVs’ direct contribution to RNFL thickness.) The location of the peak RNFL thickness in the superior (blue circle) and inferior (red circle) disc regions was determined along with the trough in the temporal region (black circle). The midpoint between the superior peak and trough amplitudes (blue vertical line) was taken as the location of the superior temporal edge and plotted, in Fig. 6B, against the location of the STva. Similarly, the location of the inferior temporal edge (red vertical line) was determined and plotted versus the location of ITva in Fig. 6C. The black line shows the locus of points expected if the temporal edges and BV locations move by equal amounts. The location of the superior and inferior temporal edges tended to move with the change in position of the BVs. There is, however, a fair degree of scatter in the data. The correlations were 0.72 (superior disc) and 0.34 (inferior disc). Figure 7 shows similar results for the SLP. The correlations were 0.72 for the superior disc and 0.43 for the inferior disc and 0.61 for the inferior disc if the one extreme outlier is not included.

FIGURE 6.

A. Method for determining the location of the leading and trailing edges of the RNFL profiles. B. The location of the superior temporal edge of the RNFL profile (blue vertical line in panel A) versus the location of the STva. C. The location of the inferior temporal edge of the RNFL profile (red vertical line in panel A) versus the location of the ITva.

FIGURE 7.

A. Same as in Fig. 6B for SLP RNFL profiles. B. Same as in Fig. 6C for SLP RNFL profiles.

The correlation between the location of the temporal edges and the location of the first temporal BV, rather than the midpoint of the ST vein and artery, were also calculated. These correlations were lower for the SLP superior and inferior edges and the OCT superior edge. Only the OCT inferior edge showed a slightly better correlation (0.40 vs. 0.34).

RNFL measure variability before and after adjusting for BV location

Recall that the horizontal solid (G-H sector) and horizontal dashed lines (quadrant) in Fig. 2 indicate the boundaries for commonly analyzed sectors around the disc: the superior and inferior temporal Garway-Heath et al arcuates and the superior and inferior quadrants. Table 1 contains the coefficient of variation [CoV=(standard deviation/mean) ×100)] of the RNFL profiles within each of these four analysis regions. For the OCT (first row), the CoVs for the shifted data were essentially the same except for the superior arcuate region (bold) where the CoV for the shifted data was slightly, 2.1%, lower. Overall, the difference in CoV ranged from −2.1% (shifted less variable) to −0.2% (unshifted less variable). Similarly, there was little evidence of improvement in CoV for the shifted SLP results (second row) where the difference in CoV ranged from −0.7% (shifted less variable) to 1.7% (unshifted less variable). None of the RNFL thicknesses for the shifted profiles were statistically different than the unshifted values.

Table 1.

Coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean in percent) for shifted and unshifted RNFL profiles.

| Superior Arcuate | Inferior Arcuate | Superior Quadrant | Inferior Quadrant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNshifted | Shifted | UNshifted | Shifted | UNshifted | Shifted | UNshifted | Shifted | |

| OCT | 15.1 | 13.0 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 15.0 | 15.1 | 12.9 | 13.1 |

| SLP | 16.3 | 16.1 | 21.0 | 20.3 | 19.7 | 21.4 | 18.4 | 19.0 |

DISCUSSION

The OCT RNFL thickness profile varies considerably among healthy controls.20 It has been suggested that taking the location of the major temporal veins and/or arteries into consideration may decrease this variability.22 We measured the location of the midpoint of the superior temporal vein and artery (STva) and of the inferior temporal vein and artery (ITva) in 50 healthy eyes. As expected,22 there was considerable variation in the location of both STva and ITva. Our purpose was to determine if adjusting for the location of these major temporal BVs would decrease the variation among individual RNFL profiles.

First, the shape of an individual’s OCT RNFL thickness profile is, in part, determined by the location of the STva and ITva. The evidence for this conclusion can be seen in Figs. 3 and 4A,B. In Fig. 3C the initial peaks of the OCT RNFL thickness profiles fall more in line after shifting each individual’s profile by the relative location of their STva. Figure 4A shows the average profiles for the individuals with the 20 most extreme STva locations, 10 on the temporal side (red) and 10 on the nasal side (blue) are shown. If the red curve were shifted by the difference in the average location of the peaks (indicated by the dashed lines) the leading (superior temporal) edge of the RNFL profile and the first peak would fall closer to the blue curve. The same is true for the trailing (inferior temporal) edge and peak of the inferior disc as shown in Fig. 4B.

Second, the OCT results are not explained simply by the direct influence of BVs on RNFL thickness. The results were similar when RNFL thickness was measured by SLP (Figs. 5 and 4C,D). The SLP data should show little, if any, direct contributions of BV thickness to RNFL thickness as BVs are not thought to contribute to SLP measurements. In fact, the SLP measure should be largely determined by the axons. 26–29

Third, the temporal edges of the RNFL profile, taken as a proxy for the edges of the arcuate bundles, are only moderately correlated with location of major temporal BVs. Although measurement error may affect these correlations, the deviations are undoubtedly due to the variation in the location of the main arcuate bundle in relation to the location of the temporal BVs, as will be illustrated below.

Finally, and most importantly, adjusting for the location of the inferior and superior temporal BVs had little effect on the variability of OCT or SLP RNFL thickness measured in the superior and inferior arcuates or quadrants. The largest improvement was < 2%.

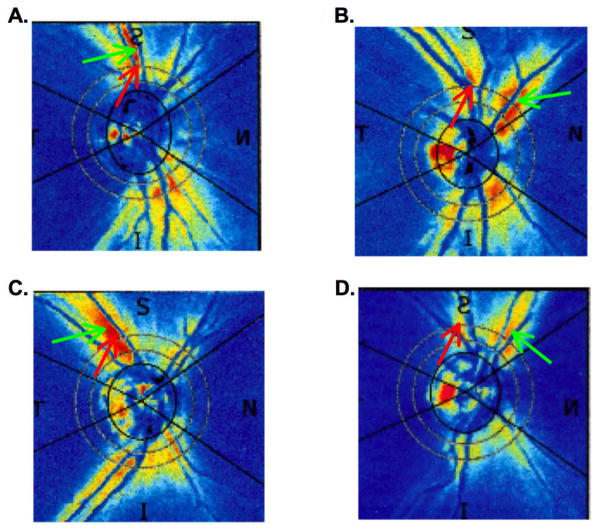

Given that there is a correlation between BV location and the RNFL profile, why didn’t shifting have a greater effect? There are at least 2 reasons. First, there is considerable variability in overall RNFL amplitude among healthy eyes. Figure 8 shows two RNFL profiles, one with a relatively large amplitude (black) and one with a relatively small amplitude (gray). Horizontal shifting for BV location will have a minimal effect on variance due to large overall amplitude differences. Second, some healthy eyes appear to have their major axon density far from the ST and IT veins and arteries. Figure 9 shows the SLP density plots for 4 healthy eyes. The red arrow shows the location of the STva and the green arrow the location of maximum signal, correlated with maximum axon thickness. The individuals represented in Fig. 9A,C are fairly typical and consistent with the maximum arcuate thickness occurring close to the STva. On the other hand, the apparent maximum in arcuate thickness in the case of the eye in Fig. 9B,D occurs some distance from the location of the STva.

FIGURE 8.

Two OCT RNFL thickness profiles that illustrate the variation in thickness possible across normal healthy eyes.

FIGURE 9.

The SLP density plots for 4 healthy eyes. The red arrow shows the location of the STva and the green arrow the location of maximum signal. See Discussion for details.

In summary, in general, the location of the major temporal BVs are associated with the location of the arcuate bundle of retinal nerve fibers. Further, the location of these BVs varies widely among individuals. However, it is not clear yet how, or if, this information can be used to improve the sensitivity/specificity of RNFL tests for glaucomatous damage.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Eye Institute grants R01-EY-09076 and RO1-EY-02115, the Joan Schechtman Research Fund of the New York Glaucoma Research Institute, New York, NY and Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991;254:1178–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuman JS, Hee MR, Puliafito CA, et al. Quantification of nerve fiber layer thickness in normal and glaucomatous eyes using optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:586–596. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100050054031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujimoto JG, Hee MR, Huang D, et al. Principles of optical coherence tomography. In: Schuman JS, editor. Optical Coherence Tomography of Ocular Diseases. Puliafito CA: Fujimoto, JG; Slack Inc; NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hee MR, Fujimoto JG, Ko T, et al. Interpretation of the optical coherence tomography image. In: Schuman JS, editor. Optical Coherence Tomography of Ocular Diseases. Puliafito CA: Fujimoto, JG; Slack Inc; NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brusini P, Salvetat ML, Zeppieri M, et al. Comparison between GDx VCC scanning laser polarimetry and Stratus OCT optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis of chronic glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:650–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budenz DL, Michael A, Chang RT, et al. Sensitivity and Specificity of the StratusOCT for perimetric glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Convento E, Midena E, Dorigo MT, et al. Peripapillary fundus perimetry in eyes with glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1398–1403. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.092973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hood DC, Harizman N, Kanadani FN, et al. Retinal nerve fiber thickness measured with optical coherence tomography (OCT) accurately detects confirmed glaucomatous damage. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:901–904. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.111252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hougaard JL, Heijl A, Bengtsson B. Glaucoma detection using different Stratus optical coherence tomography protocols. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:251–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang ML, Chen HY. Development and comparison of automated classifiers for glaucoma diagnosis using Stratus optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4121–4129. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeoung JW, Park KH, Kim TW, et al. Diagnostic ability of optical coherence tomography with a normative database to detect localized retinal nerve fiber layer defects. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:2157–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanamori A, Nagai-Kusuhara A, Escano MF, et al. Comparison of confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, scanning laser polarimetry and optical coherence tomography to discriminate ocular hypertension and glaucoma at an early stage. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:58–68. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, et al. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer, optic nerve head, and macular thickness measurements for glaucoma detection using optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, et al. Influence of disease severity and optic disc size on the diagnostic performance of imaging instruments in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1008–1015. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nouri-Mahdavi K, Hoffman D, Tannenbaum DP, et al. Identifying early glaucoma with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez-Galeana C, Bowd C, Blumenthal EZ, et al. Using optical imaging summary data to detect glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1812–1818. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00768-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah NN, Bowd C, Medeiros FA, et al. Combining structural and functional testing for detection of glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1593–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wollstein G, Ishikawa H, Wang J, et al. Comparison of three optical coherence tomography scanning areas for detection of glaucomatous damage. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zangwill LM, Williams J, Berry CC, et al. A comparison of optical coherence tomography and retinal nerve fiber layer photography for detection of nerve fiber layer damage in glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghadiali Q, Hood DC, Lee C, et al. An analysis of normal variations in retinal nerve fiber layer thickness profiles measured with optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:333–340. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181650f8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Budenz DL, Fredette MJ, Feuer WJ, Anderson DR. Reproducibility of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber thickness measurements with stratus OCT in glaucomatous eyes. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hood DC, Fortune B, Arthur SN, et al. Blood vessel contributions to retinal nerve fiber layer thickness profiles measured with optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:519–528. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181629a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hood DC, Kardon RH. A framework for comparing structural and functional measures of glaucomatous damage. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26:688–710. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay KY, Sandler SF, Raza AS, Xin D, Liebmann JM, Odel JG, Ritch R, Hood DC. Frequency domain optical coherence tomography confirms a major contribution of blood vessels to retinal nerve fibre layer profiles. Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garway-Heath DF, Poinoosawmy D, Fitzke FW, Hitchings RA. Mapping the visual field to the optic disc in normal tension glaucoma eyes. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1809–15. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Q, Knighton RW. Light scattering and form birefringence of parallel cylindrical arrays that represent cellular organelles of the retinal nerve fiber layer. Applied Optics. 1997;36:2273–2285. doi: 10.1364/ao.36.002273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang XR, Knighton RW. Linear birefringence of the retinal nerve fiber layer measured in vitro with a multispectral imaging micropolarimeter. J Biomed Opt. 2002;7:199–204. doi: 10.1117/1.1463050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang XR, Knighton RW. Microtubules contribute to the birefringence of the retinal nerve fiber layer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4588–4593. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortune B, Wang L, Cull G, Cioffi GA. Intravitreal colchicine causes decreased RNFL birefringence without altering RNFL thickness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:255–261. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]