Summary

Estimation of an HIV incidence rate based on a cross-sectional sample of individuals evaluated with both a sensitive and less-sensitive diagnostic test offers important advantages to incidence estimation based on a longitudinal cohort study. However, the reliability of the cross-sectional approach has been called into question because of two major concerns. One is the difficulty in obtaining a reliable external approximation for the mean “window period” between detectability of HIV infection with the sensitive and less-sensitive test, which is used in the cross-sectional estimation procedure. The other is how to handle false negative results with the less-sensitive diagnostic test; that is, subjects who may test negative–implying a recent infection–long after they are infected. We propose and investigate an augmented design for cross-sectional incidence estimation studies in which subjects found in the recent infection state are followed for transition to the non-recent infection state. Inference is based on likelihood methods which account for the length-biased nature of the window periods of subjects found in the recent infection state, and relate the distribution of their forward recurrence times to the population distribution of the window period. The approach performs well in simulation studies and eliminates the need for external approximations of the mean window period and, where applicable, the false negative rate.

Keywords: Cross sectional studies, Incidence rate, Prevalence estimators

1. Introduction

The availability of accurate estimates of the incidence rate of HIV is important for tracking the epidemic as well as for planning prevention trials. The most direct way of estimating HIV incidence is from longitudinal studies that follow a cohort of uninfected subjects over time, with periodic assessment of whether they become HIV infected. However, such studies are expensive, time-consuming, and often infeasible in the developing world (Institute of Medicine, 2008). An alternative approach for estimating HIV incidence rates that has become popular over the last decade is based on a single cross-sectional sample from the population of interest, in which subjects found to be positive with a sensitive diagnostic test for HIV infection are given a less-sensitive diagnostic test (see, for example, Brookmeyer and Quinn, 1995; Janssen et al., 1998). By combining the number of subjects who are negative on the sensitive test, the number who are positive on the sensitive test but negative on the less-sensitive test (commonly termed “recent infections”), and an external approximation for the mean time between detectability with the sensitive and less-sensitive tests (commonly termed “window period”), one can obtain an estimate of the HIV incidence rate. Variations of this method can be applied to other settings, including situations where not all subjects are given the same battery of tests, and can be extended to allow the assessment of covariate effects (see, for example, Balasubramanian and Lagakos, 2009). An important advantage of the cross-sectional approach is that the assessment can be much quicker and less expensively than a longitudinal cohort study. However, multiple investigators have noted that some important limitations of the cross-sectional approach must be overcome before it can be reliably used (McDougal et al., 2006; Karita et al., 2007; Sakarovitch et al., 2007; Hargrove et al., 2008; Institute of Medicine, 2008).

The first concern is obtaining a reliable external approximation of the mean window period. In part, this has been due to the limited number of longitudinal cohort studies undertaken to estimate the mean window period for different types of less-sensitive assays, as well as the considerable uncertainty in some of the estimates of the mean window period; see, for example, Janssen et al. (1998) who investigate a detuned ELISA assay, and Parekh et al. (2002), who examine a BED capture enzyme immunoassay (BED). However, there is also evidence that the window period may vary with clade of HIV (Parekh et al., 2002) and possibly other factors (Karita et al., 2007), which creates additional uncertainty about the reliability of external estimates.

A second concern is that some less-sensitive diagnostic tests, such as the BED capture enzyme immunoassay (Parekh et al., 2002), can yield false negative results in the sense that some subjects will repeatedly test negative for long periods after becoming infected. Ignoring this leads to an overestimate of HIV incidence rate. Some authors have modified the cross-sectional incidence estimator to account for such false negatives. However, this requires knowledge of the false negative rate, which is not in general available. Moreover, the few available external estimates have considerable variability. For example, McDougal et al. (2006) note that in the datasets they examined, the estimated false negative rates ranged from 2.2% to 7.9%.

In this paper we develop inference methods for estimating HIV incidence based on an augmented cross-sectional design which aims to overcome the limitations noted above. The approach is based on augmenting a traditional cross-sectional sample by following those subjects found in the recent infection state for departures from this state. By relating the forward recurrence time distribution of time from detection until leaving the recent infection state to the population window period distribution, we estimate the mean window period for use in the estimation of the HIV incidence rate, thereby avoiding the need for an external approximation for the mean window period. The augmented design also addresses concerns arising from false negative results.

In Section 2 we describe the underlying model and observations, introduce the augmented design, and develop inference methods when the less-sensitive test is not subject to false negative results. In Section 3 we extend the augmented design to account for less-sensitive diagnostic tests subject to false negative results. In Section 4 we present simulation studies of the performance of the approach, and in Section 5 we illustrate the approach with examples. Section 6 discusses some related issues.

2. Augmented Cross-Sectional Designs

2.1 Model, Standard Cross-Sectional Design

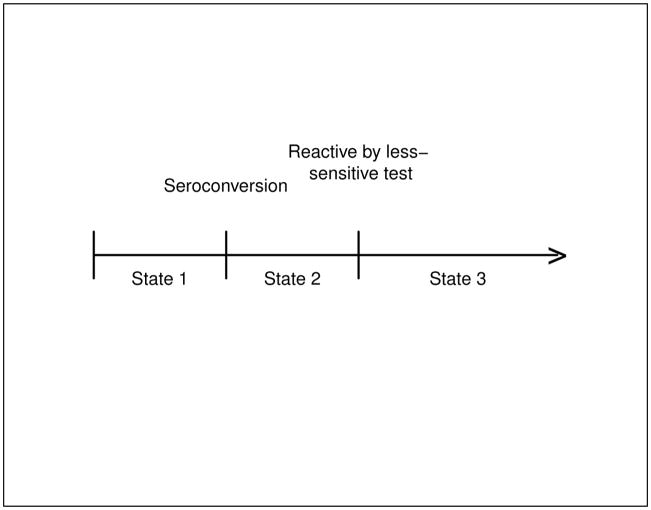

Consider the 3-state progressive-disease model in Figure 1, where State 1 represents the pre-seroconversion state (uninfected or infected but not producing HIV antibodies), State 2 represents the “recent infection” state, in which an infected individual is detectable by the sensitive diagnostic test (typically, the ELISA antibody assay) but not yet by the less-sensitive test (typically a de-tuned ELISA or BED assay), and State 3 represents the “non-recent infection” state in which an infected individual is detectable by both the sensitive and less-sensitive diagnostic tests. Throughout this paper we use “recent infection” to mean being in State 2, and not in a strictly literal sense (such as “within 6 months of seroconversion”).

Figure 1.

Three State Model

Suppose time 0 denotes birth and T denotes the calendar time of HIV seroconversion, and let f(u), λ(u) and F(u) denote the density, incidence rate (hazard function) and cumulative distribution functions of T at time u ≥ 0. An individual’s sojourn time in state S2 is denoted by the random variable W, with cumulative distribution function G(·). We assume that T and W are independent; that is, the age at seroconversion is independent of the duration of time in the recent infection state. Denote the upper limit of support for W by W*. The assumption of a finite W* means that all infected subjects will eventually test positive with the less-sensitive diagnostic test. The situation where some subjects may not become positive on the less-sensitive test by W* is considered in the next section.

Let t denote the calendar time of the cross-sectional sample. For practical settings, W* < t. Suppose that f(u) is constant, say f(u) = f, for u ∈ (t − W*, t), in which case the incidence rate at time t is f/{1 − F (t)}, which we hereafter denote by λ. Since W* is of the order of 1 year in practice, this assumption corresponds to a constant density and approximately constant incidence rate in the year preceding the cross-sectional sample. Such an assumption is reasonable in typical HIV testing settings, but may not be in settings where the epidemic is just beginning. Our main interest is in making inferences about λ, the HIV incidence rate at the time, t, of the cross-sectional sample.

Suppose that a random sample of size N is drawn from a population of asymptomatic individuals at calendar time t, and tested using both a sensitive and less-sensitive diagnostic test. In practice, the less-sensitive test is typically given only when the sensitive test is positive, and assumed to be negative if the sensitive test is negative. Let N1, N2, and N3 denote the numbers of subjects who test negative on both tests (State 1), positive only on the sensitive test (State 2), and positive on both tests (State 3), respectively. The maximum likelihood estimator of λ from the model in Figure 1 (Kaplan and Brookmeyer, 1999; Balasubramanian and Lagakos, 2009) is given by

| (1) |

where μ = E(W) is the mean window period in the recent infection state. Variations of (1) using slightly different denominator terms were introduced by Brookmeyer and Quinn (1995) and Janssen et al. (1998). To compute this estimator, N1 and N2 are obtained from the cross-sectional sample and μ is assumed to be known and obtained from the literature.

2.2 Augmented Cross-Sectional Designs

Consider a subject tested at time t who is found to be in State 2. The conditional density of the subject’s overall sojourn time in State 2, denoted g(w | t), is (Appendix 1)

| (2) |

where g(·) denotes the p.d.f. corresponding to G(·). Note that g(w | t) does not depend on t, and differs from the unconditional density, g(w) of W. Equation (2) reflects the length-biased sampling arising from the fact that individuals with larger values of W are more likely to be detected as recent infections in a cross-sectional sample. The conditional mean time in state 2 for someone found to be in the recent infection state is

| (3) |

For someone found in State 2 at time t, let X denote the elapsed time between t and when they enter State 3. It is shown in Appendix 1 that the conditional density of X, denoted h(x | t), equals {G(t + x) − G(x)}/μ. For any practical setting, t > W*, in which case

| (4) |

which also is independent of t. The relationship in equation (4) also arises as the equilibrium distribution of the forward recurrence time in a point process (Cox and Miller, 1965). The relationship between X and W suggests a design in which subjects found in State 2 be followed for transition into State 3, as such information can provide information about μ. We refer to such a design as an augmented cross-sectional study. In typical HIV applications, < 5% of the sampled subjects will be found to be in the State 2, and thus the augmented design consists of following only a small subset of the original sample.

Suppose that a random sample of n of the N2 subjects found in State 2 (recent infection) are monitored periodically, using the less-sensitive test, for entrance into State 3. The ith such subject gives rise to an interval censored observation, say [ai, bi], of the corresponding forward recurrence time Xi. Here ai denotes the elapsed time between t and the last negative test result, and bi denotes the elapsed time between t and the first positive test result. If subject i has not entered State 3 during the follow-up period, we take bi = ∞ to denote that Xi is right-censored at ai. The observations from the augmented cross-sectional design are thus given by (N1, N2, N3, n, (ai, bi), i = 1, …, n). If H(x | t) denotes the cumulative distribution function corresponding to h(x | t), the likelihood function is:

| (5) |

where φ = 1 − F(t) and π1(t), π2(t), π3(t) denote the prevalence probabilities in State 1, 2, or 3, respectively.

If μ were known, the maximum likelihood estimators of λ and φ are given by (1) and N1/N, respectively (Balasubramanian and Lagakos 2009). When G(·), and hence μ, is unknown, we show in Appendix 2 that the maximizing solutions for (φ, λ, G) can be obtained by first maximizing L2(G) with respect to G(·), yielding μ̂, and then maximizing L1(φ, λ, μ̂) with respect to (φ, λ), where μ̂ denotes the maximum likelihood estimator of μ obtained from maximizing L2(G). Denote the resulting maximum likelihood estimator of (φ, λ) by (φ̂, λ̂). It follows that λ̂ is given by (1) with μ replaced by μ̂, and that φ̂ = N1/N.

Now consider the estimation of μ from L2. One approach would be to use the relationship μ = 1/h(0 | t), which follows from (4). However, precise nonparametric estimators of h(0 | t) would not be attainable because of the typical sample sizes used in an augmented design. Alternatively, H(· | t) could be estimated nonparametrically based on the interval censored observations (ai, bi), i = 1, ···, n, and this could be applied to (4) to obtain estimators of G and μ. However, as shown by Turnbull (1974), a distribution function estimated nonparametrically from interval censored observations is only identifiable at a subset of the values of (a1, ···, an, b1, ···, bn). Hence, this approach would not lead to an identifiable estimator of μ.

We instead consider estimation of μ based on a parametric form for G(·), say G(·| θ) for some parameter vector θ. For example, let θ = (γ, k) and suppose that G is the Weibull distribution; that is, G(u | γ, k) = 1 − exp{− (u/γ)k}, for some γ > 0 and k > 0. Then μ= γΓ(1+1/k), where is the Gamma function, and L2 can be expressed as

| (6) |

This can be maximized numerically to find the maximum likelihood estimator of (μ, k), say (μ̂, k̂).

An estimate of the covariance matrix of (φ̂, λ̂, θ̂) is provided from the sample Fisher information (Appendix 4) corresponding to L. An approximate 95% confidence interval for λ is given by

| (7) |

where s denotes the estimated standard error for λ̂.

3. Augmented Designs for Less-Sensitive Tests Subject to False Negative Results

For commonly-used less-sensitive tests, the mean window period typically ranges from four to six months. However, some less-sensitive diagnostic tests, such as BED, can produce “false negative” results in the sense that a subject may repeatedly test negative, suggesting a recent infection, long after becoming infected (e.g., greater than one year). Such false negatives could reflect host immunological control of the HIV. The possibility of a false negative rate has led to proposed modifications of (1); see, for example, McDougal et al. (2006), Hargrove et al. (2008), and Welte et al. (2009). However, as McDougal et al. (2006) and others have indicated, the false negative rate is not, in general, reliably known. Thus, use of an external estimate of the false negative rate might lead to severely biased estimates of λ and confidence intervals with inadequate coverage.

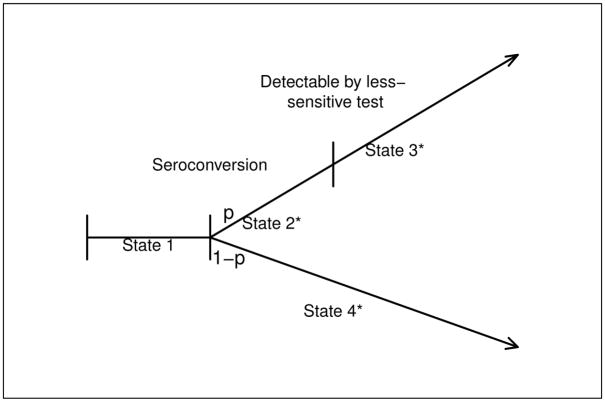

One approach for handling a less-sensitive test that is subject to false negative results is to combine it with another less sensitive test. The combination of 2 less-sensitive antibody assays (Vironostika detuned ELISA and Uni-Gold Recombigen rapid test) has been suggested by Constantine et al. (2003) to more reliably diagnose recently infected subjects. Similarly, based on results in Fiebig et al. (2003), a Western Blot test could be combined with a BED or detuned ELISA diagnostic test. In applying this approach to the estimation of incidence, negativity on both tests would define the recent infection state, and the mean window period μ would be defined as the average elapsed time between seroconversion and detectability with either less-sensitive test. If the resulting false negative rate for the combined battery is negligible, then the standard incidence estimator (1) can be used. In practice, a limitation of this approach is that the window period is shorter, and could result in too few subjects in the recent infection state. For example, the less-sensitive assay may be the BED assay and the additional diagnostic test may be a Western Blot. Fiebig et al. (2003) have shown that a Western Blot with a visible p31 band develops, on average, approximately 69 days following seroconversion. As an alternative approach, we develop a modification to the proposed augmented design by expanding the 3-state model to a 4-state model that incorporates a false negative rate (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Four State Model

Suppose that a proportion, 1 − p, of subjects evaluated with the less-sensitive diagnostic test will always test negative following infection, and that for the remaining subjects, the sojourn time in the recent infection state will be no greater than W*. For example, in a study of acute and recently-infected subjects using the ELISA (sensitive) and Vironostika (less sensitive) detuned ELISA assay, Novitsky and colleagues find that all subjects who became positive on the detuned assay do so by 1 year following seroconversion (personal communication). With this expanded model, State 1 corresponds to that in Figure 1, but we now distinguish subjects testing as recent infections into those who would eventually become positive on the less sensitive test (State 2*) and those would not (State 4*), and let State 3* denote subjects that have become positive on the less sensitive test. This model reduces to that in Figure 1 when p = 1. Let G*(·) and μ* denote the c.d.f. and mean window period in State 2*. The parameter p is related to the probability that a subject with an apparent recent infection is actually in State 2* by

| (8) |

As before, we summarize the results of a cross-sectional sample of size N by N1, N2, and N3, except that now N2 represents the number of subjects in either State 2* or 4*, while N3 represents the number in State 3*. We further write N2 = n1 + n0, where n1 and n0 denote the numbers of subjects that will and will not become positive on the less-sensitive assay by W *. Note that n1 and n0 are not observable from the cross-sectional sample, but will be observable if the n subjects are followed for at least W * time units following detection. The likelihood function corresponding to the expanded model is given by (see Appendix 3)

| (9) |

As before, the maximum likelihood estimator, μ̂*, of μ* can be obtained by maximizing only L2(G*), and thus that the maximum likelihood estimator of (φ, λ, p) can be obtained by maximizing L1(φ, λ, p, μ*). This gives

| (10) |

and

| (11) |

where

| (12) |

An estimated covariance matrix and confidence interval for λ can be obtained from the sample information (Appendix 4). When n0 = 0, p̂ = 1, (11) reduces to the estimator in (1).

4. Simulation Studies

To assess the performance of the proposed methods, we conducted simulation studies, beginning with the methods proposed in Section 2. For specific values of N, φ, λ, μ, and , we simulated data from augmented cross-sectional studies in which subjects found to have recent infections were followed biweekly until they entered State 3. The model parameters (φ, λ, μ) were estimated assuming a Weibull model for G(·). Table 1 summarizes the results where time is measured in years, λ = 0.02, 0.05, and φ = .8, and when the underlying distribution of time in State 2 follows a Weibull distribution with parameters (γ, k) selected to give c = .3 or .5 and μ = .3 and .5 years. Each row of Table 1 represents a different setting and reflects the average results based on 1000 simulated experiments.

Table 1.

Simulation results for model in Figure 1, with φ = .8 and varying λ. Estimation based on assuming Weibull G. The visit frequency is every 2 weeks. E(μ̂) and sd(μ̂) denote average and standard deviation of estimates from 1000 simulated studies. E{sdL(μ̂)} and E{sdL(λ̂)} denote average of likelihood-based estimates of the standard deviations for μ̂ and λ̂ from the 1000 simulated studies. Coverage denotes the percentage of experiments in which the true λ is in the nominal 95% confidence intervals.

| c | μ | E(N2) | N | E(μ̂) | sd(μ̂) | E{sdL(μ̂)} | E(λ̂) | sd(λ̂) | E{sdL(λ̂)} | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ = .02 | ||||||||||

| .3 | .3 | 30 | 6251 | .305 | .050 | .050 | .020 | .0055 | .0053 | 95.5% |

| 50 | 10417 | .305 | .039 | .038 | .020 | .0040 | .0039 | 94.0% | ||

| 100 | 20834 | .301 | .028 | .028 | .020 | .0028 | .0028 | 95.0% | ||

| .5 | 30 | 3750 | .500 | .086 | .082 | .021 | .0057 | .0055 | 95.3% | |

| 50 | 6250 | .508 | .065 | .064 | .020 | .0041 | .0040 | 94.4% | ||

| 100 | 12500 | .501 | .048 | .046 | .020 | .0029 | .0028 | 94.9% | ||

| .5 | .3 | 30 | 6251 | .315 | .075 | .071 | .020 | .0072 | .0066 | 92.7% |

| 50 | 10417 | .308 | .059 | .056 | .020 | .0052 | .0049 | 92.5% | ||

| 100 | 20834 | .306 | .041 | .039 | .020 | .0034 | .0028 | 93.6% | ||

| .5 | 30 | 3750 | .525 | .121 | .117 | .020 | .0068 | .0064 | 92.3% | |

| 50 | 6250 | .516 | .090 | .092 | .020 | .0047 | .0048 | 94.0% | ||

| 100 | 12500 | .508 | .065 | .066 | .020 | .0035 | .0036 | 94.4% | ||

| λ = .05 | ||||||||||

| .3 | .3 | 30 | 2500 | .305 | .049 | .052 | .050 | .0133 | .0131 | 96.6% |

| 50 | 4167 | .302 | .040 | .039 | .051 | .0103 | .0101 | 93.9% | ||

| 100 | 8334 | .303 | .028 | .028 | .050 | .0069 | .0069 | 95.3% | ||

| .5 | 30 | 1500 | .508 | .079 | .081 | .051 | .0130 | .0131 | 96.0% | |

| 50 | 2500 | .506 | .066 | .064 | .050 | .0105 | .0100 | 93.4% | ||

| 100 | 5000 | .504 | .048 | .046 | .050 | .0072 | .0069 | 93.5% | ||

| .5 | .3 | 30 | 2500 | .313 | .071 | .070 | .051 | .018 | .016 | 92.9% |

| 50 | 4167 | .308 | .055 | .056 | .050 | .012 | .012 | 94.3% | ||

| 100 | 8334 | .304 | .040 | .040 | .050 | .009 | .008 | 94.3% | ||

| .5 | 30 | 1500 | .521 | .122 | .116 | .051 | .0173 | .0164 | 93.9% | |

| 50 | 2500 | .516 | .096 | .093 | .051 | .0126 | .0122 | 93.5% | ||

| 100 | 5000 | .507 | .068 | .065 | .050 | .0088 | .0085 | 94.4% | ||

In all cases, the average values of the maximum likelihood estimators of φ (available upon request), the mean window period μ and the HIV incidence rate λ are close to the true values. In addition, the average of the estimated standard errors of μ̂ and λ̂, obtained from the observed Fisher information, are in close agreement with the empirical estimates of these standard errors obtained by averaging the 1000 simulated estimates. The last column of Table 1 gives the empirical coverage of the 95% confidence interval for λ obtained from (9), and it is seen that coverage rates are generally close to nominal values.

We next assessed the performance of the approach to the frequency with which recently-infected subjects are followed for entrance into the non-recent state (see Table 2). Expanding the visit interval from 2 weeks to either 4 or 8 led to accurate estimates of μ, λ, and the standard error of λ̂. In a few settings the estimated standard error of μ̂ was somewhat larger than the true standard error. However, when the visit frequency was enlarged to 16 weeks (available upon request), the estimated standard errors for both μ̂ and λ̂ often overestimated their true counterparts, indicating that it would be prudent to not implement such long intra-visit intervals.

Table 2.

Simulation results for model in Figure 1, with φ = .8, λ = .02 and varying visit frequencies. Estimation based on assuming Weibull G. The visit frequency is every 2 weeks. E(μ̂) and sd(μ̂) denote average and standard deviation of estimates from 1000 simulated studies. E(λ̂) and sd(λ̂) are defined similarly. E{sdL(μ̂)} and E{sdL(λ̂) } denote average of likelihood-based estimates of the standard deviations for μ̂ and λ̂ from the 1000 simulated studies. Coverage denotes the percentage of experiments in which the true λ is in the nominal 95% confidence intervals.

| c | μ | E(N2) | N | E(μ̂) | sd(μ̂) | E{sdL(μ̂)} | E(λ̂) | sd(λ̂) | E{sdL(λ̂)} | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every 4 Weeks | ||||||||||

| .3 | .3 | 30 | 6251 | .302 | .052 | .058 | .021 | .0056 | .0056 | 95.7% |

| 50 | 10417 | .307 | .040 | .040 | .020 | .0041 | .0040 | 94.6% | ||

| 100 | 20834 | .303 | .029 | .029 | .020 | .0028 | .0028 | 96.4% | ||

| .5 | 30 | 3750 | .506 | .085 | .086 | .020 | .0053 | .0053 | 95.9% | |

| 50 | 6250 | .507 | .066 | .065 | .020 | .0039 | .0040 | 95.9% | ||

| 100 | 12500 | .502 | .046 | .047 | .020 | .0027 | .0028 | 96.7% | ||

| .5 | .3 | 30 | 6251 | .316 | .076 | .079 | .020 | .0068 | .0067 | 92.7% |

| 50 | 10417 | .309 | .060 | .056 | .020 | .0053 | .0050 | 93.5% | ||

| 100 | 20834 | .305 | .042 | .040 | .020 | .0036 | .0034 | 94.4% | ||

| .5 | 30 | 3750 | .524 | .124 | .116 | .020 | .0069 | .0065 | 93.9% | |

| 50 | 6250 | .516 | .099 | 092 | .020 | .0053 | .0049 | 92.9% | ||

| 100 | 12500 | .505 | .066 | .066 | .020 | .0034 | .0034 | 95.9% | ||

| Every 8 Weeks | ||||||||||

| .3 | .3 | 30 | 6251 | .301 | .050 | .081 | .021 | .0055 | .0064 | 98.2% |

| 50 | 10417 | .304 | .042 | .052 | .020 | .0042 | .0045 | 98.0% | ||

| 100 | 20834 | .306 | .029 | .035 | .020 | .0028 | .0030 | 97.0% | ||

| .5 | 30 | 3750 | .507 | .083 | .132 | .020 | .0052 | .0055 | 97.2% | |

| 50 | 6250 | .507 | .067 | .070 | .020 | .0040 | .0041 | 96.3% | ||

| 100 | 12500 | .503 | .049 | .048 | .020 | .0029 | .0028 | 95.3% | ||

| .5 | .3 | 30 | 6251 | .321 | .074 | .086 | .020 | .0074 | .0073 | 96.4% |

| 50 | 10417 | .310 | .063 | .062 | .020 | .0060 | .0055 | 93.9% | ||

| 100 | 20834 | .309 | .042 | .043 | .020 | .0035 | .0035 | 94.8% | ||

| .5 | 30 | 3750 | .517 | .122 | .126 | .021 | .0068 | .0068 | 95.2% | |

| 50 | 6250 | .516 | .094 | .095 | .020 | .0047 | .0050 | 95.0% | ||

| 100 | 12500 | .504 | .063 | .067 | .020 | .0033 | .0034 | 95.4% | ||

To assess the robustness of the approach as regards correct specification of G(·), we reran the simulation studies but with G(·) taken to have the lognormal distribution, yet still assuming that G is Weibull to obtain an estimate of μ. The results, organized in the same way as Table 1, are shown in Table 3, with each row displaying the average results from 1000 simulated experiments. The proposed methods continue to provide accurate estimates of μ and λ, and lead to confidence intervals with coverage close to the nominal level.

Table 3.

Simulation Results for Mis-Specified Model in Figure 1 with λ = 0.02 and varying φ. Estimation based on assuming Weibull G and data generated under Lognormal G with c = .3. The visit frequency is every 2 weeks. E(μ̂) denotes average of estimates from 1000 simulated studies. E(λ̂) and sd(λ̂) denote average and standard deviation of estimates from 1000 simulated studies. E{sdL(λ̂)} denote average of likelihood-based estimates of the standard deviations for λ̂ from the 1000 simulated studies. Coverage denotes the percentage of experiments in which the true λ is in the nominal 95% confidence intervals.

| μ | N | E(N2) | E(μ̂) | E(λ̂) | sd(λ̂) | E{sdL(λ̂)} | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| φ = . 8 | |||||||

| .3 | 6251 | 30 | .290 | .021 | .0058 | .0061 | 96.4% |

| 10417 | 50 | .290 | .021 | .0043 | .0045 | 95.7% | |

| 20834 | 100 | .285 | .021 | .0030 | .0032 | 96.2% | |

| .5 | 3750 | 30 | .485 | .022 | .0063 | .0061 | 96.2% |

| 6250 | 50 | .481 | .021 | .0043 | .0046 | 95.9% | |

| 12500 | 100 | .475 | .021 | .0030 | .0032 | 95.0% | |

| .8 | 2344 | 30 | .776 | .021 | .0060 | .0060 | 94.8% |

| 3907 | 50 | .765 | .021 | .0044 | .0046 | 95.4% | |

| 7813 | 100 | .758 | .021 | .0031 | .0032 | 94.1% | |

| φ = .9 | |||||||

| .3 | 5556 | 30 | .290 | .021 | .0063 | .0061 | 95.7% |

| 9260 | 50 | .288 | .021 | .0046 | .0046 | 95.4% | |

| 18519 | 100 | .285 | .021 | .0031 | .0032 | 94.3% | |

| .5 | 3334 | 30 | .485 | .021 | .0056 | .0059 | 95.5% |

| 5556 | 50 | .481 | .021 | .0045 | .0046 | 94.4% | |

| 11112 | 100 | .474 | .021 | .0030 | .0032 | 94.1% | |

| .8 | 2084 | 30 | .769 | .022 | .0059 | .0060 | 94.3% |

| 3473 | 50 | .767 | .021 | .0044 | .0046 | 94.9% | |

| 6945 | 100 | .758 | .021 | .0030 | .0032 | 95.7% | |

We next conducted simulations for the setting addressed in Section 3, where a proportion 1−p of infected subjects never become positive on the less-sensitive test. For φ = .85, λ = .04, p = .95, c = .4 or .6, and μ* = .5 or .7, Table 4 gives the results for N chosen to give expected 30 or 50 subjects who test positive on the sensitive test and negative on the less-sensitive test, based on assuming a Weibull G for inferences. The top portion of Table 4 summarizes the results when the data have a Weibull distribution. The maximum likelihood estimates of φ (available upon request), p, μ* and λ are all close to their theoretical counterparts, and their estimated variances are close to their actual variances. The coverage of the approximate 95% confidence intervals for λ are very close to the nominal values. Thus, for these settings, use of an augmented design provides accurate estimation of the HIV incidence rate without relying on external estimates for the mean window period or false negative rate.

Table 4.

Simulation Results for Model in Figure 2, with φ = .85, λ = .04, and p = .95. Estimation based on assuming Weibull G. E(·) and sd(·) denote average and standard deviation of estimates from 1000 simulated studies. E(sdL(·)) denote average of likelihood-based estimates of the standard deviations for estimates from the 1000 simulated studies. Coverage denotes the percentage of experiments in which the true λ is in the nominal 95% confidence intervals.

| c | μ | N | E(N2) | E(p̂) | sd(p̂) | E(sdL(p̂)) | E(μ̂) | sd(μ̂) | E(sdL(μ̂)) | E(λ̂) | sd(λ̂) | E(sdL(λ̂)) | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| true G ~Weibull | |||||||||||||

| .4 | .5 | 1858 | 30 | .9496 | .0129 | .0130 | .512 | .098 | .099 | .041 | .0115 | .0117 | 95.8% |

| 3096 | 50 | .9504 | .0104 | .0100 | .510 | .078 | .078 | .040 | .0092 | .0088 | 93.8% | ||

| .7 | 1327 | 30 | .9500 | .0159 | .0152 | .713 | .150 | .136 | .041 | .0126 | .0120 | 93.7% | |

| 2212 | 50 | .9496 | .0123 | .0120 | .712 | .114 | .109 | .040 | .0090 | .0088 | 94.3% | ||

| .6 | .5 | 1858 | 30 | .9500 | .0129 | .0129 | .527 | .137 | .134 | .042 | .0159 | .0147 | 93.1% |

| 3096 | 50 | .9505 | .0102 | .0100 | .513 | .107 | .106 | .041 | .0108 | .0108 | 94.0% | ||

| .7 | 1327 | 30 | .9503 | .0157 | .0152 | .739 | .197 | .190 | .041 | .0154 | .0143 | 93.0% | |

| 2212 | 50 | .9497 | .0121 | .0119 | .724 | .147 | .149 | .040 | .0104 | .0107 | 95.0% | ||

| true G ~ Log-normal | |||||||||||||

| .4 | .5 | 1858 | 30 | .9496 | .0128 | .0130 | .477 | .103 | .111 | .044 | .0134 | .0142 | 96.0% |

| 3096 | 50 | .9502 | .0099 | .0100 | .467 | .077 | .087 | .044 | .0097 | .0107 | 96.1% | ||

| .7 | 1327 | 30 | .9503 | .0156 | .0152 | .657 | .168 | .188 | .046 | .0180 | .0173 | 95.8% | |

| 2212 | 50 | .9505 | .0120 | .0118 | .641 | .129 | .144 | .046 | .0126 | .0128 | 94.3% | ||

| .6 | .5 | 1858 | 30 | .9498 | .0130 | .0130 | .466 | .126 | .141 | .046 | .0169 | .0180 | 96.1% |

| 3096 | 50 | .9502 | .0103 | .0100 | .451 | .094 | .106 | .047 | .0124 | .0135 | 95.1% | ||

| .7 | 1327 | 30 | .9502 | .0164 | .0152 | .621 | .211 | .226 | .052 | .0239 | .0244 | 95.6% | |

| 2212 | 50 | .9504 | .0123 | .0118 | .604 | .148 | .176 | .049 | .0151 | .0169 | 96.2% | ||

The bottom portion of Table 4 examines the robustness of the approach with Weibull assumption when underlying data arise from a log-normal distribution. Here the mean window periods are slightly underestimated, which leads to a somewhat over-estimation of λ. The standard error estimates for λ̂ is also slightly over-estimated. The actual coverage of the confidence intervals for λ is nonetheless close to the nominal values. Similar results were obtained when p = .99 and φ = .75 (available upon request).

We next examine the reverse situation, where estimation is based on assuming a lognormal G and data are simulated under either a lognormal distribution, or a Weibull distribution (Table 5). When the underlying data arise from a lognormal distribution (top portion of Table 5), the proposed methods produce accurate estimates for μ* and λ and the actual coverage of the confidence intervals is close to the nominal level. However, when the underlying data arise from a Weibull distribution and estimation is based on a lognormal distribution (bottom portion of Table 5), we observe over-estimation of μ* and under-estimation of λ. The standard error estimates for λ̂ is also underestimated, which yields confidence intervals that are too liberal, with actual coverage smaller than the nominal level. Based on these results, use of a Weibull assumption for inference appears to be more robust.

Table 5.

Simulation Results for Model in Figure 2, with φ = .85, λ = .04, and p = .95. Estimation based on assuming lognormal G. E(·) and sd(·) denote average and standard deviation of estimates from 1000 simulated studies. E(sdL(·)) denote average of likelihood-based estimates of the standard deviations for estimates from the 1000 simulated studies. Coverage denotes the percentage of experiments in which the true λ is in the nominal 95% confidence intervals.

| c | μ | N | E(N2) | E(p̂) | sd(p̂) | E(sdL(p̂)) | E(μ̂) | sd(μ̂) | E(sdL(μ̂)) | E(λ̂) | sd(λ̂) | E(sdL(λ̂)) | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| true G ~ Log-normal | |||||||||||||

| .4 | .5 | 1858 | 30 | .9502 | .0134 | .0130 | .509 | .093 | .108 | .040 | .0107 | .0105 | 95.0% |

| 3096 | 50 | .9500 | .0104 | .0101 | .507 | .074 | .068 | .040 | .0084 | .0080 | 93.1% | ||

| .7 | 1327 | 30 | .9499 | .0157 | .0154 | .714 | .139 | .137 | .041 | .0114 | .0106 | 93.1% | |

| 2212 | 50 | .9501 | .0120 | .0119 | .706 | .102 | .094 | .040 | .0084 | .0081 | 94.7% | ||

| .6 | .5 | 1858 | 30 | .9500 | .0132 | .0129 | .522 | .126 | .106 | .041 | .0130 | .0117 | 91.1% |

| 3096 | 50 | .9499 | .0103 | .0101 | .510 | .084 | .084 | .040 | .0089 | .0090 | 94.8% | ||

| .7 | 1327 | 30 | .9494 | .0158 | .0153 | .722 | .165 | .152 | .041 | .0135 | .0122 | 94.2% | |

| 2212 | 50 | .9498 | .0117 | .0119 | .718 | .128 | .117 | .040 | .0096 | .0090 | 93.9% | ||

| true G ~Weibull | |||||||||||||

| .4 | .5 | 1858 | 30 | .9502 | .0133 | .0130 | .541 | .097 | .091 | .038 | .0102 | .0092 | 91.4% |

| 3096 | 50 | .9498 | .0103 | .0101 | .539 | .079 | .061 | .038 | .0080 | .0071 | 91.1% | ||

| .7 | 1327 | 30 | .9501 | .0158 | .0154 | .747 | .138 | .156 | .039 | .0102 | .0095 | 92.0% | |

| 2212 | 50 | .9494 | .0122 | .0119 | .752 | .108 | .084 | .038 | .0079 | .0071 | 92.0% | ||

| .6 | .5 | 1858 | 30 | .9497 | .0134 | .0130 | .575 | .141 | .106 | .037 | .0127 | .0104 | 86.8% |

| 3096 | 50 | .9498 | .0099 | .0101 | .571 | .106 | .083 | .036 | .0086 | .0076 | 87.0% | ||

| .7 | 1327 | 30 | .9504 | .0153 | .0152 | .810 | .184 | .148 | .037 | .0115 | .0100 | 87.1% | |

| 2212 | 50 | .9502 | .0118 | .0119 | .801 | .147 | .117 | .036 | .0086 | .0076 | 85.1% | ||

5. Illustrative Examples

To illustrate the proposed methods, we present 2 examples, one reflecting the augmented design discussed in Section 2, where the less-sensitive test is not subject to false negatives, and another where it is assumed that the less-sensitive test is subject to an unknown false negative rate. Because the proposed augmented design has not yet, to our knowledge, been implemented, we use simulated data.

We first generated a data set from the model in Figure 1, with N = 3000, φ = .8, λ = .03, and where G is a lognormal distribution with mean μ = 0.5 years and coefficient of variation c = .3. We further assume that 70% of persons found to have a recent infection are followed every 4 weeks until they are observed to have left State 2. Table 6(a) provides the results. Thus, N2 = 34 of the 3000 tested subjects were found to have a recent infection, and n = 24 of these were followed every 4 weeks. Using the methods in Section 2, with G assumed to have a Weibull distribution, the estimated maximum likelihood estimators (estimated standard errors) are φ̂ = .795 (.0078), λ̂ = .024 (.0048), and μ̂ = .61 (.076). Despite fitting the wrong parametric form for G, the resulting approximate 95% confidence interval for λ is (.016, .035), which is consistent with the true underlying parameter value.

Table 6.

Results from 2 Augmented Cross-Sectional Designs

| Table 6(a): N=3000 Subjects. Subjects in Recent Infection State Followed Every 4 Weeks. Less sensitive test not subject to false negatives (p = 1). | ||

|---|---|---|

| N1 = 2383 N2 = 34 N3 = 583 n = 24 | ||

| ai | bi | frequency |

| 0 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | 8 | 3 |

| 8 | 12 | 6 |

| 12 | 16 | 4 |

| 20 | 24 | 2 |

| 24 | 28 | 3 |

| 28 | 32 | 1 |

| 32 | 36 | 2 |

| Table 6(b): N=4000 Subjects. Subjects in Recent Infection State Followed every 2 Weeks. Less sensitive tests subject to false negatives (p < 1). | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 = 2978 N2 = 56 N3 = 966 (n1, n0) = (50, 6) | |||||

| ai | bi | frequency | ai | bi | frequency |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 24 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 24 | 26 | 2 |

| 4 | 6 | 4 | 26 | 28 | 2 |

| 6 | 8 | 1 | 28 | 30 | 1 |

| 8 | 10 | 2 | 30 | 32 | 3 |

| 10 | 12 | 7 | 34 | 36 | 2 |

| 12 | 14 | 7 | 40 | 42 | 1 |

| 14 | 16 | 2 | 42 | 44 | 1 |

| 16 | 18 | 5 | 46 | 48 | 1 |

| 18 | 20 | 3 | 52 | +∞ | 6 |

| 20 | 22 | 1 | |||

We reanalyzed the data in Table 6(a) based on what would be observed if subjects were followed every 8 weeks instead of every 4 weeks. The resulting maximum likelihood estimates (estimated standard errors) for φ were virtually unchanged. The maximum likelihood estimates (estimated standard errors) for λ and μ were .026 (.0055) and .55 (.099). The corresponding 95% confidence interval for λ was (.017, .039). All results are consistent with the true underlying parameter values. As expected, less frequent visits led to increase in the standard error for μ̂, but the confidence intervals for λ are only slightly wider for the 8-week schedule than the 4-week schedule.

We next generated a data set from the model described in Section 3, with a cross-sectional sample of size N = 4000, and with φ = .75, λ = .04, and with G* having a lognormal distribution with mean μ* = .5 years and coefficient of variation c = .4. This distribution for G* yields a negligible probability (.008) of W exceeding 1 year. We assume that a proportion 1 − p = .01 of individuals who become infected never become positive on the less-sensitive assay. From (8), this implies that the probability that an apparent recent infection is truly in State 2* is 0.86.

Suppose that subjects found to be in the recent infection state are followed biweekly for 1 year. We applied the methods described in Section 3, assuming a Weibull distribution is assumed for G*. The resulting data are presented in Table 6(b), and yield maximum likelihood estimators (estimated standard errors) of φ̂ = .745 (.0069), λ̂ = .030 (.0066), μ̂ = .57 (.095), and p̂ = .9941 (.0024), which closely approximate the true values. The corresponding estimate of the above probability is 0.89, and the estimated 95% approximate confidence interval for λ is (.019, .046).

6. Discussion

The use of a battery of sensitive and less-sensitive diagnostic tests offers an important advantage to other approaches for estimating incidence rates. However, as several authors have noted, the usefulness this approach has been hampered by the lack of reliable external estimates of the mean window period μ and the false negative rate. The methods developed in this paper attempt to circumvent these limitations by following subjects detected in the recent infection state and them employing likelihood methods to internally estimate μ and the false negative rate. The approach performs well in simulation studies, even when the parametric assumption for the distribution of the sojourn time in the recent infection state is mis-specified. Software for the analyses described in Sections 2 and 3 is available online at “http://people.hsph.harvard.edu/~lagakos/IncidenceEstimation.doc”. The proposed methods extend in a straightforward way to the 4-state model considered by Balasubramanian and Lagakos (2009).

The proposed methods assume that n of the N2 subjected detected in the recent infection state would be followed. In practical applications, N2 will typically be a very small proportion of the tested individuals, and thus it would be logistically feasible to follow all N2. However, some may not consent to be followed. Provided that the decision to be followed is independent of the underlying time in State 2, as would usually be expected, the resulting n subjects actually followed is a random sample of the N2 subjects, and hence the proposed methods apply. For the methods described in Section 2, the precision of the estimator of μ will be greatest if all n subjects are followed until they leave State 2. However, methods still apply with shorter follow-up periods in which only some of the n subjects are observed to progress to State 3. For example, for many settings, 3 bimonthly follow-up visits would be adequate.

The incremental costs of the augmented design are modest. For example, a cross-sectional sample of 4000 subjects using ELISA and a detuned ELISA from a population with a 30% prevalence of HIV would lead to 4000 ELISA tests and approximately 1200 detuned ELISA tests. If the underlying incidence rate were 3% and the mean window period were 6 months, one would expect to find approximately 42 persons detected with a recent infection. If all of these were followed bimonthly, the incremental cost of test kits and processing would increase costs by less than 5%. However, practical experience with the use of the augmented design will no doubt lead to efficiencies in its implementation.

Recent evidence suggests that use of antiretroviral treatments can affect the performance of less-sensitive diagnostic tests. Current international guidelines for the management of HIV-infected persons include consideration of antiretroviral treatment initiation when CD4 counts fall below 350 cells/mm3 or when an AIDS-defining clinical event occurs (World Health Organization, 2006). However, such initiation usually occurs several years following seroconversion and well beyond the follow-up period for recently infected subjects. In the event that some subjects do initiate antiretroviral treatments during the follow-up period, the methods proposed in this paper can still be applied, but with their forward recurrent times censored at the time of initiation of treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant AI24643 from the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to Vladimir Novitsky for helpful discussions and to the Editor, the Associate Editor and two reviewers for their comments which have led to an improved version of the paper.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Conditional Distributions of W and X, given in State 2 at time t

The state prevalence probabilities at time t are given by (Balasubramanian and Lagakos, 2009)

and

Since π2(t) = μf, we have for 0 < w < W * that

Now consider the conditional distribution of X. For x > 0

Appendix 2: Maximizing Likelihood Function (5)

We use (5) to develop the profile likelihood function for μ. Since L2(G) does not depend on (φ, λ),

| (A.1) |

and

| (A.2) |

Setting (A.1) and (A.2) equal to 0 yields

| (A.3) |

The profile likelihood function for (μ, G) is thus

| (A.4) |

Substituting (A.3) into (A.4) shows that L1 is constant in (μ, G). It follows that the maximum likelihood estimator of G(·), and hence also of μ, can be obtained by maximizing L2(G), and that the maximum likelihood estimator of (φ, λ) is obtained from (A.3), with μ replaced by μ̂.

Appendix 3: Likelihood Function for the Model in Section 3

Let denote the prevalence of State j at time t for the 4-state process in Figure 2, for j = 1, ···, 4, and assume that W * < t, and f(u) = f for u ∈ (t − W *, t). It follows directly from Balasubramanian and Lagakos (2009) that . Since the probability of entering States 2* and 3* is p, the probability of being in State 2* at time t is

Similarly,

By subtraction, .

Since a negative sensitive test result means that a subject is in State 1, the likelihood contribution for the observations (N1, n1, n0, N3) is

which reduces to (9). Using the same methods as in Appendix 2, it can be shown that the maximum likelihood estimator of μ* is obtainable by maximizing only L2(G*) in (9). It follows that the maximum likelihood estimators of (φ, λ, p) can be obtained by maximizing L1(φ, λ, p, μ̂) with respect to (φ, λ, p), which leads to (10)–(12).

Appendix 4: Estimated Variance of Maximum Likelihood Estimators

We derive the estimated covariance matrix for the maximum likelihood estimators of the parameters (φ, λ, p, μ*) for the model in Figure 2. The covariance matrix for the model in Figure 1 corresponds to the special case where p is known and equal 1. Assume that G(·) is a Weibull distribution with mean μ* and shape parameter k. The likelihood function can be written

The Fisher information matrix consists of contributions from the N subjects. If the ith subject tests negative on the sensitive test, the likelihood contribution is ℓi = log(φ). Taking partial derivatives with respect to the parameters yields , and . If the subject tests positive on both tests, the likelihood contribution is ℓi = log(p) + log(1 − φ − λφμ*). This yields , and . If the subject is found to be in State 4* ℓi = log(1−p)+log(1− φ), leading to , and . Finally, if the subject is found to be in State 2*,

and the corresponding partials are (details available upon request)

where is the derivative of the gamma function Γ(x) evaluated at .

Define and . The Fisher covariance matrix estimate for (λ̂, φ̂, μ̂, p̂) is given by M−1 where:

where Λ is the N × 4 matrix with ith row being and Ω = (ω1, ω2, ···, ωN)′. The estimated covariance matrix is obtained by replacing the unknown parameters in M by their maximum likelihood estimators.

References

- Balasubramanian R, Lagakos SW. Estimating HIV incidence based on combined prevalence testing. Biometrics. 2009 Apr 13; doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01242.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R, Quinn TC. Estimation of current Human Immunodeficiency Virus incidence rates from a cross-sectional survey using early diagnostic tests. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;141:166–172. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantine NT, Sill AM, Jack N, Kreisel K, Edwards J, Cafarella T, Smith H, Bartholomew C, Cleghorn FR, Blattner WA. Improved classification of recent HIV-1 infection by employing a two-stage sensitive/less-sensitive test strategy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2003;32:94–103. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200301010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR, Miller HD. The Theory of Stochastic Processes. Methuen and Company, Ltd; London: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, Garrett PE, Schumacher RT, Peddada L, Heldebrant C, Smith R, Conrad A, Kleinman SH, Busch MP. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS. 2003;17:1871–1879. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove JW, Humphrey JH, Mutasa K, Parekh BS, McDougal JS, Ntozinie R, Chidawaniyika H, Moulton LH, Ward B, Nathoo K, Iliff PJ, Kopp E. Improved HIV-1 incidence estimates using the BED capture enzyme immunoassay. AIDS. 2008;22:511–518. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2a960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagakos SW, Gable A, editors. Institute of Medicine. Methodological Challenges in HIV Biomedical Prevention Trials. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen RS, Satten GA, Stramer SL, Rawal BD, O’Brien TR, Weiblen BJ, Hecht FM, Jack N, Cleghorn J, Kahn JO, Chesney MA, Busch MP. New testing strategy to detect early HIV-1 infection for use in incidence estimates and for clinical and prevention purposes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:42–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EH, Brookmeyer R. Snapshot Estimators of Recent HIV Incidence Rates. Operations Research. 1999;47:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Karita E, Price M, Hunter E, Chomba E, Allen S, Fei L, Kamali A, Sanders EJ, Anzala O, Katende M, Ketter N the IAVI Collaborative Seroprevalence and Incidence Study Team. Investigating the utility of the HIV-1 BED capture enzyme immunoassay using cross-sectional and longitudinal seroconverter specimens from Africa. AIDS. 2007;21:403–408. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801481b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougal JS, Parekh BS, Peterson ML, Branson BM, Dobbs T, Ackers M, Gurwith M. Comparison of HIV type I incidence observed during longitudinal follow-up with incidence estimated by cross-sectional analysis using the BED capture enzyme immunoassay. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2006;22:945–952. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh BS, Kennedy MS, Dobbs T, Pau C, Byers R, Green T, Hu DJ, Vanichseni S, Young NL, Choopanya K, Mastro TD, McDougal S. Quantitative detection of increasing HIV Type 1 antibodies after seroconversion: A simple assay for detecting recent HIV infection and estimating incidence. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2002;18:295–307. doi: 10.1089/088922202753472874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakarovitch C, Rouet F, Murphy G, Minga AK, Alioum A, Dabis F, Costagliola D, Salamon R, Parry JV, Barin F. Do Tests Devised to Detect Recent HIV-1 Infection Provide Reliable Estimates of Incidence in Africa? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;45:115–122. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318050d277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull BW. Nonparametric estimation of a survivorship function with doubly censored data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1974;69:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Welte A, McWalter TA, Bärnighausen T. A simplified formula for inferring HIV incidence from cross-sectional surveys using a test for recent infection. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2009;25:125–126. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: Recommendations for a public health approach. 2006 http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/artadultguidelines.pdf. [PubMed]