Abstract

Background:

The use of synthetic analogues of somatostatin following pancreatic surgery is controversial. The aim of this meta-analysis is to determine whether prophylactic somatostatin analogues (SAs) should be used routinely in pancreatic surgery.

Methods:

Randomized controlled trials were identified from the Cochrane Library Trials Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Citation Index Expanded and reference lists. Data were extracted from these trials by two independent reviewers. The risk ratio (RR), mean difference (MD) and standardized mean difference (SMD) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) based on intention-to-treat or available case analysis.

Results:

Seventeen trials involving 2143 patients were identified. The overall number of patients with postoperative complications was lower in the SA group (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.62–0.82), but there was no difference between the groups in perioperative mortality (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.68–1.59), re-operation rate (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.56–2.36) or hospital stay (MD −1.04 days, 95% CI −2.54 to 0.46). The incidence of pancreatic fistula was lower in the SA group (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.53–0.78). The proportion of these fistulas that were clinically significant is not clear. Analysis of results of trials that clearly distinguished clinically significant fistulas revealed no difference between the two groups (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.34–1.41). Subgroup analysis revealed a shorter hospital stay in the SA group than among controls for patients with malignant aetiology (MD −7.57 days, 95% CI −11.29 to −3.84).

Conclusions:

Somatostatin analogues reduce perioperative complications but do not reduce perioperative mortality. However, they do shorten hospital stay in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery for malignancy. Further adequately powered trials of low risk of bias are necessary.

Keywords: pancreatic resection, somatostatin, octreotide, pancreatic fistula, systematic review

Introduction

Pancreatic resection is performed to treat pancreatic diseases including malignancy and chronic pancreatitis. In most series, the incidence of complications following pancreatic surgery varies from 30% to 60% and the mortality rate is <5%.1–3 The major complication following pancreatic resection is postoperative pancreatic leak or fistula. Recent reviews have described the incidence of pancreatic leak or fistula as 37%.4 Various methods have been suggested to decrease the incidence of pancreatic complications, but the most common approach has involved the use of somatostatin or its synthetic analogues. Somatostatin and its analogues decrease the exocrine and endocrine pancreatic secretions by binding to the somatostatin receptors on the exocrine and endocrine cells, and decrease the secretions of these cells possibly by acting as dephosphorylators and by altering the calcium transport across the cell membranes.5 Decreasing the volume of pancreatic secretion may decrease the incidence of pancreatic leak or fistula.6 However, the use of somatostatin and its analogues is controversial and whereas some randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews recommend7,8 prophylactic somatostatin analogues (SAs) in pancreatic resections, others do not.9,10 These treatments may potentially decrease morbidity and mortality following pancreatic surgery, but it is possible that they may have no therapeutic benefit and may be associated with negative outcomes. A systematic review was carried out to determine whether prophylactic SAs should be used routinely in pancreatic surgery.

Materials and methods

Identification of trials and data extraction

Only RCTs of parallel design, irrespective of blinding, sample size, publication status (i.e. whether published as full text or presented only as an abstract at a conference) and language, were included. Quasi-randomized trials and other study designs were excluded. Only trials involving patients undergoing a pancreatic surgical procedure (pancreatic resection, pancreatic duct drainage procedures or cyst drainage procedures) for any pancreatic disease were considered. Only trials involving the administration of perioperative somatostatin (or an analogue of this hormone, such as octreotide) against a comparator of placebo or no intervention were considered. The Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group Controlled Trials Register,11 the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE and Science Citation Index Expanded12 were searched for trials published up to November 2009. The references of the identified trials were also searched to identify further relevant trials.

Two reviewers (RSK and KSG) independently identified the trials for inclusion. In addition, the population characteristics (such as sex, age, proportion of pancreaticoduodenectomies, disease aetiology) and the interventions used in each trial were extracted. The methodological qualities of the trials were assessed independently, without masking the trial names. Any unclear or missing information was obtained by contacting the authors of the individual trials. If there was any doubt as to whether trials had shared the same patients – completely or partially (by identifying common authors and centres) – the authors of the trials were contacted to establish whether the trial report had been duplicated. Any differences in opinion were resolved through discussion.

Outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were extracted: postoperative mortality; re-operation; postoperative complications (anastomotic leak, pancreatic fistula, pancreatitis, sepsis, renal failure, bleeding, abdominal collections, infected abdominal collections, delayed gastric emptying, pulmonary complications, shock, number of complications, number of patients with any complications); drug-related complications (treatment withdrawal, number with adverse effects resulting from treatment), and hospital stay (total hospital stay, intensive care unit [ICU] stay). Pancreatic fistula has been graded as A, B and C by consensus amongst surgeons.13 Any pancreatic fistula, however defined, was included by the authors as one of the outcomes. Clinically significant pancreatic fistula was included as another outcome, for which only trials which featured data on grades B and C as distinct from grade A (not clinically significant) were included.

Subgroup analyses of trials with low risk of bias vs. those with high risk of bias, different interventions (somatostatin and octreotide), different aetiologies (malignancy and chronic pancreatitis), different procedures (pancreatoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy and pancreatic drainage procedures) and different methods of management of the pancreatic stump (pancreatogastrostomy and pancreatojejunostomy) were planned.

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias can result in the incorrect estimation of the effectiveness of an intervention.14–17 The risk of bias in the trials was assessed in different domains, including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (of participants, personnel and outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias, such as baseline imbalance, early stopping bias, academic bias and sources of funding bias.18,19 Trials which were classified as being at low risk of bias in sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data and selective outcome reporting were considered as low bias-risk trials.

Statistical methods

Meta-analyses were performed according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration18 using the software package Revman 5.0 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). For dichotomous outcomes, the risk ratio (RR) was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes, the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) was calculated with its 95% CI. A random-effects model20 and a fixed-effect model21 were used. In cases of discrepancy between the two models, both the results were reported; otherwise only the results from the fixed-effect model were reported. The analysis was performed on an ‘intention-to-treat’ basis22 whenever possible, but, in order to allow for dropouts and withdrawals between randomization and intervention or control, the ‘available case analysis’18 was adopted. The degree of heterogeneity was measured by chi-squared test with significance set at a P-value of 0.10, and the quantity of heterogeneity was measured by I2.23 An I2 value >30% was considered to represent statistically significant heterogeneity. Standard deviation was imputed from standard error or from P-values if it was not given directly in the trial reports, according to Cochrane Collaboration guidelines.18 The chi-squared test for subgroup differences set at a P-value of 0.05 was performed to identify any subgroup differences.

A funnel plot was used to explore bias.24,25 Asymmetry in the funnel plot of trial size against treatment effect was used to assess the risk of bias. The linear regression approach was performed to determine the funnel plot asymmetry.24

Results

Description of studies

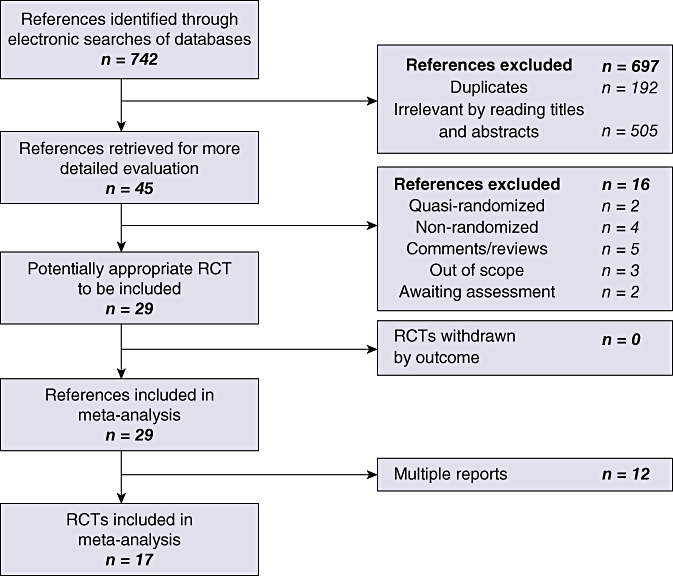

A total of 742 references were identified through electronic searches of the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group Controlled Trials Register11 and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (n= 74), MEDLINE (n= 390), EMBASE (n= 176), Science Citation Index Expanded (n= 102). A total of 192 duplicates and 505 clearly irrelevant references identified by reading the abstracts were excluded (Fig. 1). Forty-five references were retrieved for further assessment. No references were identified through scanning the reference lists of the RCTs identified. Of the 45 references, 16 were excluded because they referred to quasi-randomized studies, prospective non-randomized studies or comments that did not contain data from an RCT. Of the remaining 29 references, 12 were multiple reports, which resulted in the identification of a total of 17 RCT reports which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. All 17 trials were completed trials and were able to provide data for the analyses. Important details of the included trials are shown in Table 1. Only two trials were considered to be at low risk of bias.26,27

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the search strategy used to identify trials. RCT, randomized controlled trial

Table 1.

Important characteristics of included studies. All trials are randomized controlled trials (parallel design)

| Author(s), year | Sample size, n | Mean age, years | Intervention | Dose |

Aetiology, n |

Pancreatoduodenectomy, n | Follow-up | Pancreatic fistula definition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malignancy | Chronic pancreatitis | ||||||||

| Beguiristain et al., 199531 | 35 | 59.4 | Somatostatin | 4.5 mg/day continuous infusion for 7 days | 30 (85.7%) | 3 (8.6%) | 35 (100%) | Not reported | ≥10 ml fluid with amylase concentration of >5 somogyi units |

| Briceno Delgado et al., 199838 | 34 | 52.5 | Octreotide | 0.1 mg s.c. t.i.d. for 7 days | 28 (82.4%) | 5 (14.7%) | Not reported | ≥50 ml/day ARF for >2 weeks | |

| Buccoliero et al., 199232 | 16 | 58.2 | Somatostatin | 250 mcg/h infusion for 6 days | NS | NS | 16 (100%) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Buchler et al., 199234 | 246 | 52 | Octreotide | 100 mcg s.c. t.i.d. for 7 days | 111 (45.1%) | 112 (45.5%) | 200 (81.3%) | 90 days | Amylase and lipase >3 times serum concentration, >3 days postop, >10 ml/h |

| Friess et al., 19958 | 247 | 48 | Octreotide | 100 mcg s.c. t.i.d. for 7 days | 0 | 247 (100%) | 124 (50.2%) | 90 days | Amylase and lipase >3 times serum level, >3 days postop, >10 ml/h |

| Gouillat et al., 200127 | 75 | 60.2 | Somatostatin | 6 mg/day infusion for 7 days | 61 (81.3%) | 4 (5.3%) | 75 (100%) | Not reported | >100 ml/day ARF (>5 times normal serum amylase), after day 3, persisting after day 12, or in association with ↑temp or symptoms requiring surgery, drainage or intensive care |

| Hesse et al., 200533 | 105 | 59.5 | Octreotide | 0.1 mg s.c. t.i.d. for 7 days | 71 (67.6%) | 26 (24.8%) | 80 (76.2%) | Not reported | >100 ml/day of ARF (>5 times normal serum amylase), after day 3, persisting after day 7, with ↑temp and preseptic conditions |

| Klempa et al., 199130 | 24 | 56.5 | Somatostatin | 250 mcg/h i.v. for 6 days | 24 (100%) | 0 | 24 (100%) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Kollmar et al., 200826 | 67 | 62.8 | Octreotide | 100 mcg s.c. t.i.d. for 7 days | 33 (49.3%) | 16 (23.9%) | 67 (100%) | Not reported | Any volume after day 3 with amylase content >3 times normal serum amylase |

| Lange et al., 199235 | 21 | 46.5 | Octreotide | s.c. 8-hourly 50 mcg on day 1, 100 mcg on day 2, 150 mcg until 3 days after drain removal | 21 (100%) | 0 | NS | Not reported | Recurrent pancreatic drainage |

| Montorsi et al., 199536 | 218 | 58.2 | Octreotide | 100 mcg s.c. t.i.d. for 7 days | 139 (63.8%) | 18 (8.3%) | 143 (65.6%) | Not reported | >10 ml/day ARF (>3 times normal serum amylase) after day 3 |

| Pederzoli et al., 199437 | 252 | 53.1 | Octreotide | 100 mcg s.c. t.i.d. for 7 days | 162 (64.3%) | 90 (35.7%) | 105 (41.7%) | Until discharge | >10 ml/day for >4 days after day 4, amylase >3 times normal |

| Sarr, 20039 | 275 | 62 | Vapreotide | 0.6 mg s.c. b.i.d for 7 days | 138 (50.2%) | 0 | 108 (39.3%) | 30 days | >30 ml/day ≥day 5, amylase or lipase >5 times normal |

| Shan et al., 200528 | 54 | 67 | Somatostatin | 250 mcg/h i.v. for 7 days | 45 (83.3%) | 0 | 54 (100%) | 60 days | >10 ml/day ARF (amylase >3 times serum level), for >7 days |

| Suc et al., 20047 | 230 | 56.5 | Octreotide | 100 mcg s.c. t.i.d. for 10 days | 154 (67%) | 30 (13%) | 177 (77%) | Not reported | Any volume with amylase >4 times normal serum value for 3 days or clinical/radiological anastomotic leak |

| Tulassay et al., 199329 | 33 | 43 | Somatostatin | 125 mcg/h infusion for 48 h | 0 | 14 (42.4%) | 0 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Yeo et al., 200010 | 211 | 64.7 | Octreotide | 100 mcg s.c. t.i.d. for 7 days | 147 (69.7%) | 22 (10.4%) | 211 (100%) | Not reported | >50 ml/day ARF (>3 times normal serum value) on or after day 10 or radiological pancreatic anastomosis disruption |

NS, not specified; s.c. subcutaneous; ARF, amylase rich fluid

Participants

The 17 trials included 2143 patients (Table 1). A total of 237 patients were involved in six trials comparing somatostatin vs. control27–32 and 1564 patients were involved in 10 trials comparing octreotide vs. control.7,8,10,27,33–38 The remaining patients were involved in one trial comparing vapreotide vs. control.9 Overall, 1457 patients underwent pancreatoduodenectomy, 1143 patients had malignancy and 587 had chronic pancreatitis in the trials that reported these characteristics. The mean age of the individuals in the trials varied between 43 years and 65 years. The mean proportion of females varied between 15% and 48%. There was no difference in the characteristics of patients in the intervention and control groups in any of the trials that reported these baseline characteristics.

Somatostatin analogues vs. no intervention

Primary outcomes

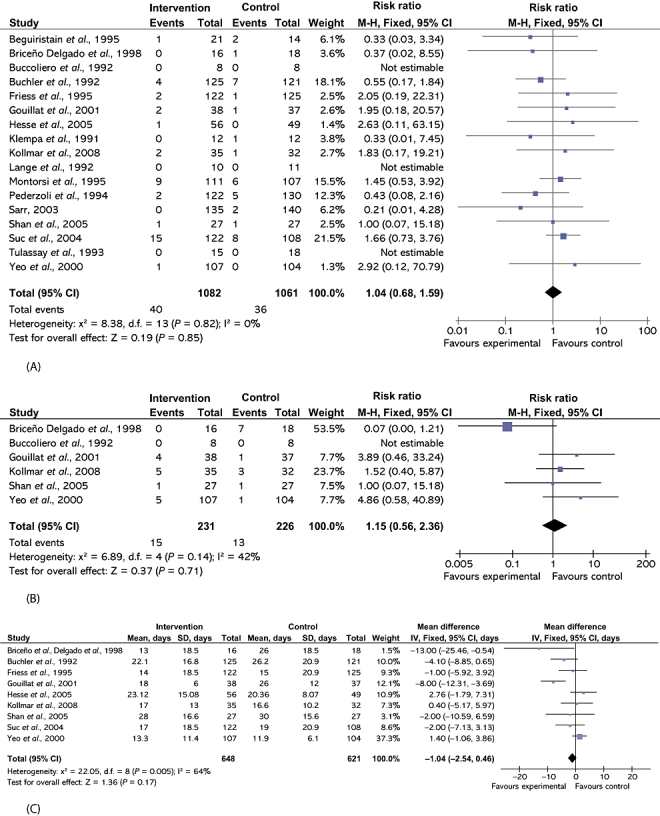

There was no difference between the two groups in either perioperative mortality (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.68–1.59) or re-operation rates (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.56–2.36) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of somatostatin analogues vs. no intervention showing effects on (A) perioperative mortality, (B) re-operation rates and (C) hospital stay. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval, SD, standard deviation

Secondary outcomes

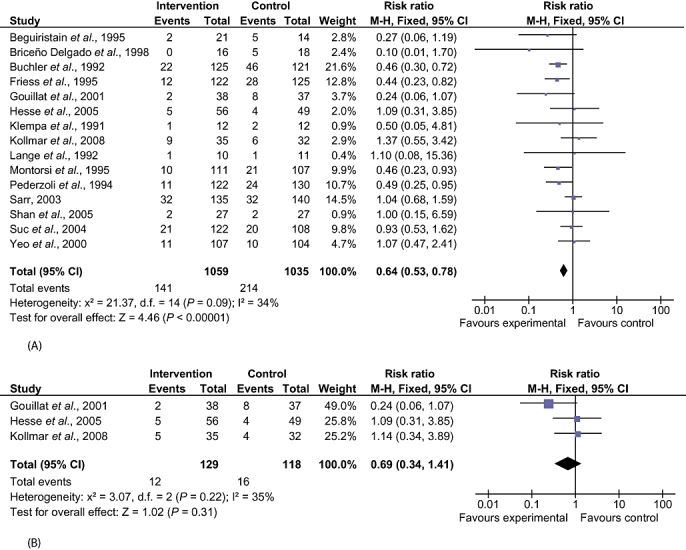

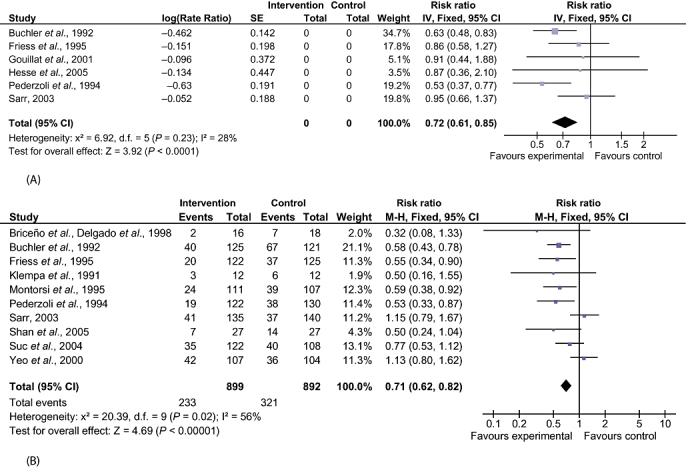

Postoperative complications

There were statistically significant lower incidences of pancreatic fistula (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.53–0.78) (Fig. 3) and sepsis (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23–0.97) in the SA group than in the control group. Likewise, decreases in the numbers of complications (rate ratio 0.72, 95% CI 0.61–0.85) and of patients with any complication (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.62–0.82) in the SA group over the control group were statistically significant (Fig. 4). There were no differences between the groups in incidences of anastomotic leak rates (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.51–1.27), clinically significant pancreatic fistulas (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.34–1.41) (Fig. 3), postoperative pancreatitis (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.32–1.22), renal failure (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.25–1.77), bleeding (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.70–1.44), abdominal collections (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.58–1.09), infected abdominal collections (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.68–1.38), delayed gastric emptying (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.52–1.28), pulmonary complications (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.54–1.36) or shock (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.41–2.05).

Figure 3.

Comparison of somatostatin analogues vs. no intervention showing effects on pancreatic fistula rates. (A) Pancreatic fistula (all): studies did not differentiate between clinically significant and clinically insignificant fistulas. (B) Pancreatic fistula (clinically significant): studies included only clinically significant fistulas. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Figure 4.

Comparison of somatostatin analogues vs. no intervention showing effects on perioperative complications. (A) Number of complications. (B) Number with any complications. SE, standard error; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Drug-related complications

There was no difference in treatment withdrawal (RR 1.55, 95% CI 0.56–4.33) or number of patients with adverse effects caused by treatment (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.95–1.71) between the groups.

Hospital stay

There was no difference in the duration of hospital stay (MD −1.04, 95% CI −2.54 to 0.46) or ICU stay (MD 0.90, 95% CI −1.76 to 3.56) between the groups.

Subgroup analysis

The following planned subgroup analyses were performed: different interventions (somatostatin and octreotide); different aetiologies (malignancy and chronic pancreatitis), and different procedures (pancreatoduodenectomy). A planned subgroup analysis of other procedures (distal pancreatectomy and pancreatic drainage procedures), and the different methods of management of pancreatic stump (pancreatogastrostomy and pancreatojejunostomy) could not be performed as the outcome data for the different subgroups were not available from the trials.

Subgroup analysis based on the risk of bias in the trials could not be performed as only two trials were at low risk of bias.26,27 There was no difference in any of the primary outcomes between intervention and control groups in the different subgroups.

The secondary outcomes for which there were statistically significant differences between the two groups are described below.

Stratified by intervention

Somatostatin vs. no intervention

The decrease in incidences of pancreatic fistula (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.14–0.88), reduced number of patients with any complications (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.27–0.93) and reduction in duration of hospital stay (MD −6.79 days, 95% CI −10.65 to −2.94; mean hospital stay 22.1 days in the somatostatin group vs. 27.6 days in controls) in the somatostatin group compared with the control group were statistically significant. There was no difference between the two groups in any of the other outcomes.

Octreotide vs. no intervention

The lower incidences of pancreatic fistula (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.49–0.77) and abdominal collections (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.42–0.89), lower number of complications (rate ratio 0.66, 95% CI 0.55–0.80) and lower number of patients with any complications (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.58–0.80) in the octreotide group compared with the control group were statistically significant. There was no difference in any of the other outcomes between the two groups.

The only outcome in which the test for subgroup differences was positive was that of hospital stay (P= 0.001).

Stratified by aetiologies

Malignancy

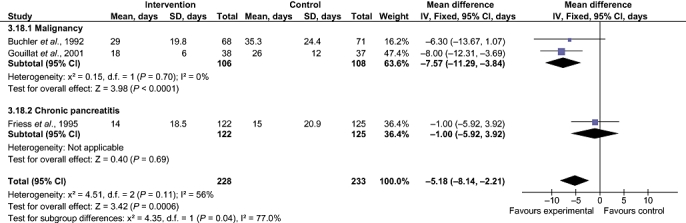

Decreases in the incidence of pancreatic fistula (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.35–0.77) and sepsis (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.08–0.97), number of complications (rate ratio 0.61, 95% CI 0.48–0.77) and number of patients with complications (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.45–0.79) in the SA group over the control group were statistically significant. The decrease in the duration of hospital stay in the SA group over that in the control group (MD −7.57 days, 95% CI −11.29 to −3.84; mean hospital stay 25.0 days in the SA group vs. 32.1 days in controls) was statistically significant (Fig. 5). There was no difference in any of the other outcomes between the two groups.

Figure 5.

Comparison of somatostatin analogues vs. no intervention. Subgroup analysis stratified by different aetiologies: effects on hospital stay. SD, standard deviation; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Chronic pancreatitisReductions in the incidence of pancreatic fistula (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.24–0.64) and number of patients with any complications (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.38–0.77) in the intervention group compared with the control group were statistically significant. There was no difference in any of the other outcomes between the two groups.

The only outcome in which the test for subgroup differences was positive was hospital stay (P= 0.03).

Stratified by procedure

A planned subgroup analysis of distal pancreatectomy and pancreatic drainage procedures could not be performed as the data for these procedures were not available from the trials. Only the subgroup of patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy was reported.

Pancreatoduodenectomy

There was no statistically significant difference between the SA and control group for any of the outcomes.

Variations in statistical analysis

Adopting the random-effects model or calculating the risk difference did not change the results. Sensitivity analysis using empirical continuity correction factors39 was not performed because there were no statistically significant outcomes in the main comparison with zero event trials.

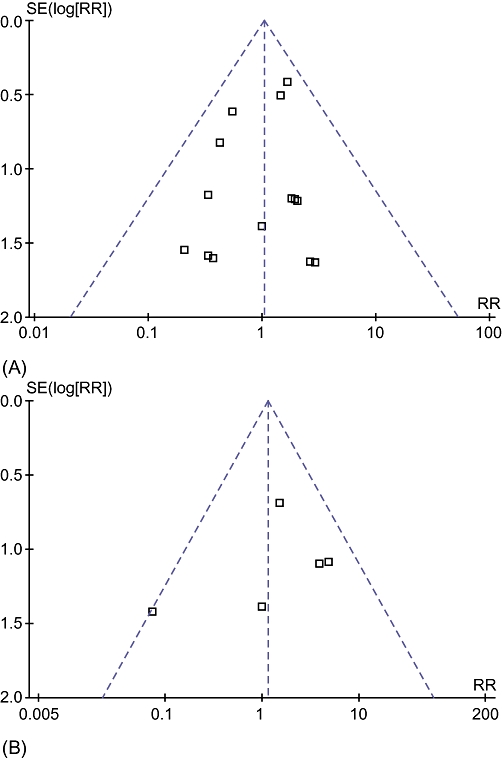

Reporting bias

The funnel plot of the primary outcomes did not show any reporting bias (Fig. 6). Egger's linear regression approach to identifying publication bias24 did not reveal any bias for the outcome perioperative mortality (P= 0.3199). This was not calculated for the outcome re-operation because few trials included that outcome.

Figure 6.

Funnel plots of comparison of somatostatin analogues vs. no intervention for outcomes (A) perioperative mortality and (B) re-operation. SE, standard error; RR, risk ratio

Discussion

Somatostatin analogues did not decrease rates of perioperative mortality and re-operation in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery. The main indication for re-operation is the presence of a pancreatic fistula-associated sepsis or organ dysfunction.13 There is no universal definition of pancreatic fistula or pancreatic leak and incidences vary depending on the definitions used. An international study group of surgeons13 have graded postoperative pancreatic fistulas by consensus as A, B and C. Grade A fistulas are transient and do not have any clinical impact. Grade B fistulas require alteration in the management of the patient. Grade C fistulas require major alterations in the management of the patient and usually indicate re-operation. Grade B and C fistulas have significant clinical impact and may contribute to increased morbidity and mortality. In this review, only trials in which data on grade B or C fistulas were available separately from grade A were included for the outcome of clinically significant pancreatic fistula (grades B and C). The overall incidence of pancreatic fistula was lower in the SA group. Only three trials distinguished between any pancreatic fistula and clinically significant pancreatic fistula.26,27,33 There was no difference between the SA and control groups in the incidence of clinically significant pancreatic fistula. It is likely that some of the pancreatic fistulas that were reported in the other trials were clinically significant. However, in the absence of data on the proportion of these fistulas that were clinically significant, such trials could not be included for the outcome ‘clinically significant pancreatic fistulas’ and could be included only for the outcome ‘all pancreatic fistulas’. That only a few trials were included under the outcome ‘clinically significant pancreatic fistulas’ may explain the lack of any statistically significant difference between the SA and control groups. Alternatively, the lack of a statistically significant difference may reflect the lack of effect. In patients undergoing pancreatic surgery for malignancy, a decrease in hospital stay was noted in the SA group. This suggests that SAs decreased clinically significant fistulas in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery for cancer.

Overall postoperative complications were lower in the intervention group than the control group. However, there was no difference between the two groups in length of hospital stay in the main analysis. The possible reasons for the absence of difference in total hospital stay include a lack of effect of SAs with regard to incidence of re-operation, anastomotic leak or clinically significant pancreatic fistulas and the fact that pancreatic fistulas are often managed at the patient's home (as community-based treatment). Pancreatic fistulas that are amenable to community-based treatment may decrease the quality of life of the patients concerned during the time they take to close, increase the length of the convalescence period, thus causing a later return to work and resulting in major cost implications for patients, patients' carers and patients' employers, and increase the costs associated with the provision of community-based treatment, despite the fact that SAs do not appear to reduce hospital stay.

As far as the interventions were concerned, somatostatin must be administered by continuous i.v. infusion for approximately 1 week. This can decrease the patient's mobility. By contrast, octreotide is administered subcutaneously thrice per day, allowing good patient mobility. Its other advantage is that it can be administered even in patients with difficult venous access, thereby increasing compliance. The adverse effects associated with the intervention were mainly minor, such as pain at the injection site. No serious adverse effects were reported in any of the trials. Of the trials that reported the withdrawal of intervention, the treatment was stopped in about 1.5% of the 540 patients. In high-income countries, the cost of an entire course of octreotide is less than the cost of 1 day in hospital. There was no difference in length of hospital stay between the two groups in the main analysis. However, the subgroup analysis revealed a shorter hospital stay in the intervention group in the somatostatin (P= 0.0006) and malignancy (P < 0.0001) subgroups. Only three trials were included in each of these subgroups,27,28,34 one of which featured in both subgroups.27 It is not clear whether the lower hospital stay in the intervention group in these subgroups is because of the intervention effect or because of the numerous subgroup analyses that were performed. The lack of information on pancreatic fistula (i.e. whether it was clinically significant or not) does not help us to reach a conclusion. Patients with chronic pancreatitis have a lower risk of postoperative complications than those with malignancy and this may be because the tissue fibrosis usually seen in patients with chronic pancreatitis facilitates the anastomotic procedure.34 This logical reasoning combined with the very low P-value obtained suggests that the decrease in hospital stay in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery for malignancy reflects the true effect of SAs. Further evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of SAs in pancreatic surgery is necessary.

Somatostatin analogues reduce perioperative complications but do not reduce perioperative mortality. In patients undergoing pancreatic surgery for malignancy, they shorten hospital stay. Further adequately powered trials of low risk of bias are necessary.

Statement

This paper is a shortened version of a review submitted to the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group. Cochrane reviews are regularly updated as new evidence emerges and in response to comments and criticisms. The Cochrane Library should be consulted for the most recent version of the review. The results of a Cochrane review can be interpreted differently, depending on the reader's perspectives and circumstances. Please consider the conclusions presented carefully. They are the opinions of the review authors and are not necessarily shared by the Cochrane Collaboration.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group for the support it provided for the completion of this review.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Alexakis N, Halloran C, Raraty M, Ghaneh P, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP. Current standards of surgery for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1410–1427. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, et al. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232:786–795. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Koniaris L, Kaushal S, Abrams RA, et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas–616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:567–579. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connor S, Alexakis N, Garden OJ, Leandros E, Bramis J, Wigmore SJ. Meta-analysis of the value of somatostatin and its analogues in reducing complications associated with pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1059–1067. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris AG. Somatostatin and somatostatin analogues: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effects. Gut. 1994;35(Suppl. 3):1–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3_suppl.s1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lembcke B, Creutzfeldt W, Schleser S, Ebert R, Shaw C, Koop I. Effect of the somatostatin analogue sandostatin (SMS 201-995) on gastrointestinal, pancreatic and biliary function and hormone release in normal men. Digestion. 1987;36:108–124. doi: 10.1159/000199408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suc B, Msika S, Piccinini M, Fourtanier G, Hay JM, Flamant Y, et al. Octreotide in the prevention of intra-abdominal complications following elective pancreatic resection: a prospective, multicentre randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2004;139:288–294. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friess H, Beger HG, Sulkowski U, Becker H, Hofbauer B, Dennler HJ, et al. Randomized controlled multicentre study of the prevention of complications by octreotide in patients undergoing surgery for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1270–1273. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarr MG. The potent somatostatin analogue vapreotide does not decrease pancreas-specific complications after elective pancreatectomy: a prospective, multicentre, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:556–564. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Sohn TA, et al. Does prophylactic octreotide decrease the rates of pancreatic fistula and other complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy? Results of a prospective randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2000;232:419–429. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forman D, Delaney B, Kuipers E, Malthaner R, Moayyedi P, Gardener E, et al. Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group. 2009. About The Cochrane Collaboration (Cochrane Review Groups [CRGs]) 1: Art. No.: UPPERGI.

- 12.Royle P, Milne R. Literature searching for randomized controlled trials used in Cochrane reviews: rapid versus exhaustive searches. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19:591–603. doi: 10.1017/s0266462303000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:982–989. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does quality of reports of randomized trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998;352:609–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–412. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, Schulz KF, Juni P, Altman DG, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2008;336:601–605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0. 2008. updated February 2008]. Cochrane Collaboration. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Accessed 10 October 2009.

- 19.Gurusamy KS, Gluud C, Nikolova D, Davidson BR. Assessment of risk of bias in randomized clinical trials in surgery. Br J Surg. 2009;96:342–349. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMets DL. Methods for combining randomized clinical trials: strengths and limitations. Stat Med. 1987;6:341–350. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newell DJ. Intention-to-treat analysis: implications for quantitative and qualitative research. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:837–841. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.5.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macaskill P, Walter SD, Irwig L. A comparison of methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2001;20:641–654. doi: 10.1002/sim.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kollmar O, Moussavian MR, Richter S, de RP, Maurer CA, Schilling MK. Prophylactic octreotide and delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a prospective randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gouillat C, Chipponi J, Baulieux J, Partensky C, Saric J, Gayet B. Randomized controlled multicentre trial of somatostatin infusion after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1456–1462. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shan YS, Sy ED, Tsai ML, Tang LY, Li PS, Lin PW. Effects of somatostatin prophylaxis after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: increased delayed gastric emptying and reduced plasma motilin. World J Surg. 2005;29:1319–1324. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7943-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tulassay Z, Flautner L, Sandor Z, Fehervari I. Perioperative use of somatostatin in pancreatic surgery. Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense. 1993;64:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klempa I, Baca I, Menzel J, Schuszdiarra V. Effect of somatostatin on basal and stimulated exocrine pancreatic secretion after partial duodenopancreatectomy. A clinical experimental study. Chirurg. 1991;62:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beguiristain A, Espi A, Balen E, Pardo F, Hernandez Lizoain JL, Alvarez CJ. Somatostatin prophylaxis following cephalic duodenopancreatectomy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1995;87:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buccoliero F, Pansini GC, Mascoli F, Mari C, Donini A, Navarra G. Somatostatin in duodenocephalopancreatectomy for neoplastic pathology. Minerva Chir. 1992;47:713–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hesse UJ, Decker C, Houtmeyers P, Demetter P, Ceelen W, Pattyn P, et al. Prospectively randomized trial using perioperative low-dose octreotide to prevent organ-related and general complications after pancreatic surgery and pancreatico-jejunostomy. World J Surg. 2005;29:1325–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buchler M, Friess H, Klempa I, Hermanek P, Sulkowski U, Becker H, et al. Role of octreotide in the prevention of postoperative complications following pancreatic resection. Am J Surg. 1992;163:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(92)90264-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lange JR, Steinberg SM, Doherty GM, Langstein HN, White DE, Shawker TH, et al. A randomized, prospective trial of postoperative somatostatin analogue in patients with neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas. Surgery. 1992;112:1033–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montorsi M, Zago M, Mosca F, Capussotti L, Zotti E, Ribotta G, et al. Efficacy of octreotide in the prevention of pancreatic fistula after elective pancreatic resections: a prospective, controlled, randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 1995;117:26–31. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Falconi M, Camboni MG. Efficacy of octreotide in the prevention of complications of elective pancreatic surgery. Italian Study Group. Br J Surg. 1994;81:265–269. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briceno Delgado FJ, Lopez CP, Rufian PS, Solorzano PG, Mino FG, Pera MC. Prospective and randomized study on the usefulness of octreotide in the prevention of complications after cephalic duodeno-pancreatectomy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1998;90:687–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Stat Med. 2004;23:1351–1375. doi: 10.1002/sim.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]