Abstract

Background Socio-economic inequalities in maternal and child health are ubiquitous, but limited information is available on how much the quality of care varies according to wealth or ethnicity in low- and middle-income countries. Also, little information exists on quality differences between public and private providers.

Methods Quality of care for women giving birth in 2004 in Pelotas, Brazil, was assessed by measuring how many of 11 procedures recommended by the Ministry of Health were performed. Information on family income, self-assessed skin colour, parity and type of provider were collected.

Results Antenatal care was used by 98% of the 4244 women studied (mean number of visits 8.3), but the number of consultations was higher among better-off and white women, who were also more likely to start antenatal care in the first trimester. The quality of antenatal care score ranged from 0 to 11, with an overall mean of 8.3 (SD 1.7). Mean scores were 8.9 (SD 1.5) in the wealthiest and 7.9 (SD 1.8) in the poorest quintiles (P < 0.001), 8.4 (SD 1.6) in white and 8.1 (SD 1.9) in black women (P < 0.001). Adjusted analyses showed that these differences seemed to be due to attendance patterns rather than discrimination. Mean quality scores were higher in the private 9.3 (SD 1.3) than in the public sector 8.1 (SD 1.6) (P < 0.001); these differences were not explained by maternal characteristics or by attendance patterns.

Conclusions Special efforts must be made to improve quality of care in the public sector. Poor and black women should be actively encouraged to start antenatal care early in pregnancy so that they can fully benefit from it. There is a need for regular monitoring of antenatal attendances and quality of care with an equity lens, in order to assess how different social groups are benefiting from progress in health care.

Keywords: Inequality, inequity, antenatal care, quality of health care

KEY MESSAGES.

In spite of near universal coverage for antenatal visits, the quality of care was consistently higher among white and high socio-economic status women than among black and poor women.

This was true for women attending both the public and the private sectors; quality was higher in the private than in the public sector, for all socio-economic and ethnic groups, and regardless of the number of attendances.

Socio-economic differences in public-sector quality of care were fully explained by the fact that the poor had fewer visits and started antenatal care late in pregnancy; ethnic group differences disappeared after adjustment for socio-economic status.

Introduction

Socio-economic inequities in maternal and child health are present throughout the world, irrespective of a country’s level of health and wealth. Survey data from low- and middle-income countries show consistent pro-rich patterns in terms of antenatal and delivery care, access to health services and coverage of preventive and curative interventions (Victora et al. 2003; Gwatkin et al. 2007; PPHCKN 2007; Boerma et al. 2008). While studies from North America unfailingly show inequities in health between ethnic groups (Williams 2002; Betancourt and Maina 2004; ACOG–Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women 2005), less is known on this topic for low- and middle-income countries—the notable exceptions being Brazil (Barros et al. 2001) and South Africa (Kon and Lackan 2008) where several studies show striking differentials. In spite of the abundance of data on inequities in access, utilization, coverage and health status, much less is known about how the quality of maternal and child health care varies according to wealth or ethnic group.

The Brazilian health care system underwent a major reorganization in the early 1990s as a consequence of the 1988 Constitution, which established that ‘health is the right of all and the State’s responsibility’. A unified national health service (Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS) was created. Preventive and curative services are provided to the whole population without any type of user fee for outpatient or inpatient care. Although the system is universal, about one-quarter of the population opt for private insurance or—less often—for out-of-pocket payments to private providers (Santos et al. 2008). These alternatives usually ensure easier access to services and their quality is perceived by the population as being higher.

The coverage of antenatal care in Brazil is very high and only 2.5% of all pregnant women fail to attend an antenatal clinic (SINASC 2005), but poor quality of care is often reported (Coimbra et al. 2003; Puccini et al. 2003; Almeida and Barros 2005). Some authors have measured adequacy of antenatal care by using composite indicators, such as the Kessner (Kessner et al. 1973) and Kotelchuck (1994) indices, which combine the number of attendances with information on gestational age at first visit. Those scores show strong pro-rich patterns (Leal et al. 2004; Almeida and Barros 2005). Few studies have investigated whether socio-economic status also affects the proportion of recommended procedures that are carried out during antenatal care (Barros et al. 2001; Puccini et al. 2003; Almeida and Barros 2005). A recent systematic review noted the paucity of studies on the actual quality of maternal and child health care broken down by socio-economic position or ethnic group (Barros and Victora 2007; PPHCKN 2007). Also, there are few studies in the literature comparing the use of maternal and child health services in the public and private sectors (Gwatkin et al. 2004) and even fewer on the quality of care in these sectors (Mills et al. 2002; Bojalil et al. 2007).

A population-based birth cohort study was carried out in southern Brazil in 2004 that provides an opportunity to investigate the quality of antenatal care. This article documents socio-economic and racial/ethnic inequalities in procedures performed during antenatal care, as well as differences between public and private providers.

Methods

Pelotas is located in the extreme south of Brazil, with a population of about 340 000 inhabitants. More than 99% of all deliveries take place in hospitals. From 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2004 inclusive, a birth cohort study attempted to enrol all births to mothers resident in the urban area. Eligible subjects for the perinatal study included all live births, as well as still births weighing at least 500g or with at least 20 weeks of gestational age. A detailed description of the methodology is given elsewhere (Barros et al. 2006). Births were identified through daily visits to the five maternity hospitals. Mothers were interviewed soon after delivery using a pre-tested structured questionnaire. Information was obtained on demographic, socio-economic, behavioural and biological characteristics, reproductive history and health care utilization.

Family income in the month prior to delivery was collected as a continuous variable (in Reais) and quintiles were constructed. Mother’s skin colour was self-reported and used as a proxy for ethnic background. Skin colour options were: white, brown, black, Asian and indigenous. Asian and indigenous women, who represent 0.3% and 0.7% of the cohort, respectively, were excluded from the analysis. Additional analyses were carried out using skin colour as rated by the interviewers.

Information on antenatal care and number of consultations was taken from existing records or, if unavailable, obtained through maternal self-report. The number of antenatal care consultations was categorized as 0, 1–3, 4–6 or ≥7. Information was collected on procedures recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (Ministério da Saúde 2006). Mothers were asked whether each of the following procedures was carried out at least once during antenatal care: measurement of uterine height and blood pressure, gynaecological and breast examination, screening for cervical cancer (Pap smear), administration of tetanus toxoid, prescription of iron and vitamins, breastfeeding counselling, and blood and urine analyses. Information was also collected on the number of ultrasound examinations, even though these are not considered essential procedures by the Ministry of Health.

Adequacy of antenatal care was studied by assigning one point to each of the above-listed procedures, resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 11. In addition, procedures were divided into three categories and separate scores were calculated: physical examination and counselling (breast and gynaecological examination, Pap test and counselling about breastfeeding; range 0–4), measurements (measurement of uterine height and blood pressure, and blood and urine analyses; range 0–4) and prescriptions (tetanus toxoid, iron and vitamins; range 0–3). We also carried out factor analyses of the 11 items, but the components arising from this method did not have a clear interpretation; for this reason the simple additive scores were adopted. Ultrasound exams were analysed separately.

Type of health insurance scheme was categorized as publicly funded Unified Health System (SUS), private insurance or out-of-pocket payment (direct payment to private providers). For some analyses, private insurance and out-of-pocket money were merged into a single category (‘private sector’) because both are carried out in private clinics.

We used χ2 tests to compare the distribution of maternal characteristics and antenatal procedures by quintiles of family income and by maternal skin colour. When appropriate, tests for linear trends were also performed. The slope index of inequality (SII) was estimated to measure the magnitude of differences in antenatal care procedures across categories of family income and maternal skin colour (Mackenbach and Kunst 1997). The SII is derived via regression of mean health outcome within a particular social group on the mean relative rank of social groups. Categories of family income and maternal skin colour were first ordered from the lowest (rank) to highest and the midpoint of the proportion of the participants in each category was estimated. The SII was then obtained by regressing each of the procedures performed during antenatal care on the midpoint score and was interpreted as the hypothetical absolute difference in outcome between the top and the bottom of the family income and maternal skin colour hierarchy.

Linear regression analysis was used to estimate the association between adequacy of antenatal care (continuous variable) and explanatory variables (family income and maternal skin colour) in separate models. In the first model family income or maternal skin colour were included alone. In the second model the other explanatory variable was added to determine whether, for example, any association between adequacy of antenatal care and family income was affected by maternal skin colour. In the third model parity was included. In the final model, we further adjusted for number of prenatal consultations and gestational age at the first consultation.

All analyses were performed with Stata software version 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Tex). The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Federal Unviersity of Pelotas, affiliated with the Brazilian Federal Medical Council. Written informed consent was obtained from women who agreed to participate in the study.

Results

A total of 4244 mothers were interviewed. Non-response rate at recruitment due to refusals was 0.75% (n = 32). There was a strong association between skin colour and family income. Black women represented 23.0% of those in the poorest quintile, and 6.9% of those in the richest. The socio-economic status of brown-colour women fell in between that of whites and blacks.

Antenatal care characteristics according to strata of family income and maternal skin colour are shown in Table 1. Attendance was nearly universal, but the number of consultations was higher among better-off and white women. These groups were also most likely to start antenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy. About four in every five women received care through SUS. Use of private insurance and out-of-pocket payments was also more common among white and better-off women.

Table 1.

Distribution of parity and antenatal care characteristics (%) by family income and maternal skin color, Pelotas 2004

| Variables | Family income (quintiles) |

Maternal skin colour |

Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (poorest) | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th (richest) | Pa | Black | Brown colour | White | Pa | ||

| Parity | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 0 | 37.8 | 33.5 | 38.4 | 39.6 | 48.1 | 35.0 | 36.9 | 41.8 | 39.5 | ||

| 1 | 23.3 | 23.6 | 26.1 | 27.7 | 29.8 | 24.6 | 24.0 | 27.4 | 26.0 | ||

| 2 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 17.4 | 17.6 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 16.3 | 16.5 | 16.1 | ||

| ≥3 | 22.9 | 26.7 | 18.1 | 15.1 | 8.8 | 26.5 | 22.8 | 14.3 | 18.4 | ||

| No. of prenatal consultations | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 0 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 2.0 | ||

| 1–3 | 10.8 | 8.6 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 10.8 | 6.9 | 3.8 | 5.7 | ||

| 4–6 | 30.2 | 30.5 | 23.7 | 16.2 | 8.6 | 27.2 | 26.8 | 18.6 | 21.9 | ||

| ≥7 | 54.8 | 58.5 | 70.2 | 80.0 | 89.1 | 58.2 | 63.9 | 76.3 | 70.4 | ||

| Gestational trimester at the | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 1st consultationb | |||||||||||

| 1st | 61.2 | 60.5 | 70.8 | 80.0 | 89.2 | 60.1 | 65.7 | 77.9 | 72.3 | ||

| 2nd | 33.8 | 36.0 | 26.8 | 18.3 | 10.4 | 35.2 | 31.1 | 20.2 | 25.1 | ||

| 3rd | 5.0 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 2.6 | ||

| ANC financing | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| SUSc | 93.6 | 96.7 | 91.7 | 80.2 | 41.7 | 90.6 | 88.0 | 75.7 | 81.0 | ||

| Out-of-pocket payment | 1.9 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 14.8 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 4.3 | ||

| Private insurance | 4.5 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 16.4 | 43.5 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 18.5 | 14.7 | ||

| Total numbers of women | 875 | 862 | 823 | 857 | 827 | – | 698 | 870 | 2581 | – | 4244 |

aX2 test.

bOnly for mothers who attended antenatal care.

cUnified Health System (free public national health service).

As expected, women who started antenatal care in the first trimester had a higher number of attendances (9.2 visits) compared with those starting in the second (6.2 visits) or third trimester (3.5 visits) (P < 0.001), with similar patterns in both the public and the private sectors. Similarly, women who started antenatal care in the first trimester had a higher mean global score of adequacy of antenatal care (8.6 out of a maximum of 11 points) compared with those starting in the second (7.7 points) or third trimester (6.9 points) (P < 0.001).

The number of procedures was studied for each insurance scheme (Table 2). Five procedures were nearly universally performed: uterine height and blood pressure measurements, blood and urine analyses, and ultrasound. Women with private insurance or who relied on out-of-pocket payments had very similar numbers of procedures, but those receiving antenatal care in the public sector presented lower frequencies in 9 of the 12 procedures. No differences were observed in three procedures: measurement of uterine height, measurement of blood pressure and administration of tetanus toxoid.

Table 2.

Procedures carried out during antenatal care (%) by insurance scheme, Pelotas 2004

| Proceduresa | Public sector |

Private sector |

Pb | Pc | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unified Health System | Out-of-pocket payment | Private insurance | ||||

| Physical examination and counselling | ||||||

| Breast examination | 49.7 | 77.1 | 84.1 | 0.029 | <0.001 | 55.9 |

| Gynecological examination | 73.3 | 89.4 | 90.8 | 0.601 | <0.001 | 76.5 |

| Screening for cervical cancer (Pap smear)d | 57.5 | 74.3 | 79.1 | 0.174 | <0.001 | 61.4 |

| Counselling about breastfeeding | 58.4 | 74.0 | 80.0 | 0.087 | <0.001 | 62.2 |

| Measurements | ||||||

| Measurement of uterine height | 99.3 | 100.0 | 99.7 | 0.444 | 0.156 | 99.4 |

| Measurement of blood pressure | 99.8 | 100.0 | 99.8 | 0.588 | 0.745 | 99.8 |

| Blood analysis | 97.5 | 99.4 | 100.0 | 0.066 | <0.001 | 98.0 |

| Urine analysis | 96.5 | 100.0 | 99.5 | 0.343 | <0.001 | 97.0 |

| Prescriptions | ||||||

| Administration of tetanus toxoidd | 76.1 | 74.4 | 75.9 | 0.681 | 0.770 | 76.0 |

| Prescription of iron | 75.9 | 82.1 | 82.1 | 0.995 | <0.001 | 77.1 |

| Prescription of vitamins | 22.2 | 44.9 | 48.6 | 0.387 | <0.001 | 27.1 |

| Any ultrasound during pregnancy | 97.4 | 98.9 | 99.5 | 0.351 | 0.001 | 97.8 |

aOnly for mothers who attended antenatal care.

bX2 test within private sector (out-of-pocket payments vs. private insurance).

cX2 test between public and private sectors.

dIncluded those women who performed the procedure before pregnancy.

Eight out of 12 procedures carried out during antenatal care showed higher frequencies among better-off women (Table 3): breast and gynaecological examination, screening for cervical cancer, counselling about breastfeeding, blood and urine analyses, prescription of vitamins and ultrasound. A similar pattern was shown by maternal skin colour, with the lowest frequencies among black women and intermediate frequencies among brown-colour women (Table 3). Although statistically significant at the 0.05 level, some of the procedures showed small absolute differences between the groups.

Table 3.

Procedures carried out during antenatal care (%) by family income (quintiles) and maternal skin colour, Pelotas 2004

| Proceduresa | Family income |

Maternal skin colour |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (poorest) | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th (richest) | Pb | SII | Black | Brown colour | White | Pb | SII | ||

| Physical examination and counselling | |||||||||||||

| Breast examination | 45.9 | 48.9 | 52.0 | 60.1 | 73.1 | <0.001 | 0.327 | 50.2 | 51.9 | 59.1 | <0.001 | 0.132 | |

| Gynecological examination | 71.3 | 70.3 | 76.0 | 79.4 | 85.9 | <0.001 | 0.191 | 72.4 | 73.8 | 78.5 | <0.001 | 0.100 | |

| Screening for cervical cancer (Pap test)c | 55.0 | 58.9 | 58.6 | 62.8 | 71.8 | <0.001 | 0.186 | 57.6 | 59.3 | 63.4 | 0.002 | 0.077 | |

| Counselling about breastfeeding | 58.0 | 59.7 | 61.1 | 60.0 | 72.5 | <0.001 | 0.145 | 62.2 | 61.2 | 62.9 | 0.570 | 0.004 | |

| Measurements | |||||||||||||

| Measurement of uterine height | 98.9 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.9 | 99.4 | 0.093 | 0.007 | 99.0 | 99.2 | 99.6 | 0.047 | 0.010 | |

| Measurement of blood pressure | 99.6 | 99.8 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.8 | 0.461 | 0.002 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 0.036 | 0.003 | |

| Blood analysis | 95.7 | 97.2 | 98.4 | 98.9 | 99.6 | <0.001 | 0.047 | 95.6 | 97.2 | 98.8 | <0.001 | 0.048 | |

| Urine analysis | 94.8 | 95.3 | 97.6 | 98.2 | 99.4 | <0.001 | 0.060 | 93.8 | 96.1 | 98.3 | <0.001 | 0.058 | |

| Prescriptions | |||||||||||||

| Administration of tetanus toxoidc | 74.4 | 76.8 | 77.1 | 77.3 | 74.3 | 0.939 | 0.002 | 76.7 | 74.6 | 76.5 | 0.797 | 0.002 | |

| Prescription of iron | 77.6 | 74.6 | 75.9 | 78.5 | 79.2 | 0.123 | 0.035 | 79.1 | 78.2 | 76.3 | 0.085 | −0.044 | |

| Prescription of vitamins | 25.8 | 18.6 | 22.8 | 28.5 | 39.9 | <0.001 | 0.189 | 23.6 | 27.7 | 27.9 | 0.046 | 0.042 | |

| Any ultrasound during pregnancy | 96.0 | 96.9 | 98.0 | 98.9 | 99.2 | <0.001 | 0.042 | 95.1 | 97.2 | 98.8 | <0.001 | 0.045 | |

SII, slope index of inequality.

aOnly for mothers who attended antenatal care.

bX2 test for trend.

cIncluded those women who performed the procedure before pregnancy.

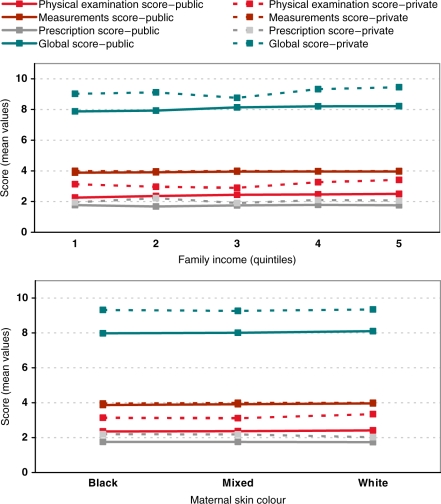

The score for adequacy of antenatal care showed an approximately normal distribution (mean 8.3, SD 1.7). Private sector users had higher global score means than women using the public sector, within all categories of family income and maternal skin colour (Figure 1). After stratification by family income, mean scores for public patients were 1.11 (SE 0.07, P < 0.001), 0.80 (SE 0.05, P < 0.001), 0.04 (SE 0.01, P = 0.008) and 0.29 (SE 0.04, P < 0.001) units lower than private patients for the global, physical examination and counselling, measurements and prescriptions scores, respectively. After stratification by skin colour, again public patients’ scores were on average 1.27 (SE 0.07, P < 0.001), 0.89 (SE 0.05, P < 0.001), 0.05 (SE 0.01, P < 0.001) and 0.32 (SE 0.03, P < 0.001) units lower than private patients, respectively.

Figure 1.

Mean values of scores of quality of antenatal care according to family income and maternal skin colour in the public and private sectors, Pelotas 2004

Even though at least one ultrasound examination was performed in 98% of women, the average number of examinations was higher in the top (3.4 examinations) than in the bottom quintiles (1.7 examinations; P < 0.001) and among whites (2.5) compared with blacks (1.7; P < 0.001).

Table 4 shows multivariable analyses for the global score. In the crude analysis, women with low income in both public and private sectors showed lower adequacy of antenatal care than better-off women. In the private sector, the lowest regression coefficient was observed in the third quintile, based on a small sample of 59 women, but the inverse linear trend with income was statistically significant. After adjusting for maternal skin colour and parity, the patterns in both sectors remain virtually unchanged. Further adjustment for the number of consultations and gestational age at the first consultation removed the differentials in the global score in the public sector. In the private sector, the same pattern observed in the crude analyses—with the lowest score in the middle quintile—is maintained but the magnitude of the regression coefficients is reduced. These analyses have to be interpreted with caution given the small numbers of private patients in the three lower quintiles (56, 28 and 67 women, respectively, compared with 167 and 481 in the two upper quintiles).

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted analyses of the association between adequacy of antenatal care global score and family income and maternal skin colour in the public and private sectors, Pelotas 2004

| Model | Variables included in the model | Family income |

Variables included in the model | Maternal skin colour |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public sector | Private sector | Public sector | Private sector | |||

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |||

| 1 | Family income (quintiles) | P < 0.001 | P = 0.002 | Maternal skin colour | P = 0.198 | P = 0.857 |

| 1st | −0.339 (0.108) | −0.430 (0.200) | Black | −0.123 (0.078) | −0.023 (0.180) | |

| 2nd quintile | −0.291 (0.107) | −0.335 (0.268) | Brown colour | −0.092 (0.073) | −0.082 (0.149) | |

| 3rd | −0.088 (0.108) | −0.687 (0.184) | White | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |

| 4th | −0.015 (0.110) | −0.119 (0.123) | ||||

| 5th | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | ||||

| 2 | Model 1 + maternal skin color | P = 0.0004 | P = 0.0009 | Model 1 + family income | P = 0.618 | P = 0.798 |

| 1st | −0.323 (0.112) | −0.462 (0.206) | Black | −0.072 (0.079) | 0.111 (0.182) | |

| 2nd | −0.261 (0.110) | −0.351 (0.271) | Brown colour | −0.045 (0.074) | −0.029 (0.149) | |

| 3rd | −0.070 (0.110) | −0.726 (0.188) | White | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |

| 4th | 0.005 (0.112) | −0.124 (0.126) | ||||

| 5th | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | ||||

| 3 | Model 2 + parity | P = 0.001 | P = 0.001 | Model 2 + parity | P = 0.745 | P = 0.827 |

| 1st | −0.302 (0.112) | −0.460 (0.206) | Black | −0.057 (0.079) | 0.111 (0.183) | |

| 2nd | −0.230 (0.110) | −0.345 (0.271) | Brown colour | −0.033 (0.074) | −0.005 (0.149) | |

| 3rd | −0.055 (0.110) | −0.722 (0.189) | White | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |

| 4th | 0.021 (0.112) | −0.108 (0.126) | ||||

| 5th | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | ||||

| 4 | Model 3 + ANC characteristicsa | P = 0.910 | P = 0.033 | Model 2 + ANC characteristicsa | P = 0.325 | P = 0.592 |

| 1st | 0.004 (0.109) | −0.342 (0.209) | Black | 0.084 (0.077) | 0.136 (0.181) | |

| 2nd | 0.012 (0.107) | −0.270 (0.268) | Brown colour | 0.092 (0.072) | 0.118 (0.149) | |

| 3rd | 0.074 (0.106) | −0.556 (0.192) | White | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |

| 4th | 0.043 (0.108) | −0.096 (0.125) | ||||

| 5th | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | ||||

ANC, antenatal care.

aAdjusted for number of prenatal consultations and gestational age at the first visit.

Additional multivariable analyses were carried out to explore the difference between the public and private sectors. Prior to adjustment, the global score in the private sector was 1.28 units higher than in the public sector. On average, women attending the private sector had 10.7 visits, compared with 7.7 in the public sector (P < 0.001), while 94.6% and 67.1%, respectively, had started antenatal care in the first trimester of gestation (P < 0.001). After adjustment for the number of attendances and gestational age at the first antenatal visit—as well as for income and skin colour—this difference was somewhat reduced but still highly significant (β = −0.92; P < 0.001). Figure 1 confirms that the differences between quality of care in the public and private sectors are more marked than differences due to socio-economic status or skin colour.

No associations were found between the antenatal adequacy score and maternal skin colour in the crude or adjusted analyses (Table 4). The number of black (n = 62) and brown-colour (n = 95) women in the private sector reduced the power of the study of associations, but no significant differences in adequacy of antenatal care were observed in any of the models.

Discussion

The frequencies of procedures carried out during antenatal care varied according to family income and maternal skin colour. These apparent inequities, however, seemed to be primarily related to attendance patterns rather than discrimination. In the public sector; the differences in the quality indicators disappeared after adjustment for the number of antenatal visits. In the private sector, the quality score remained lowest in the middle quintile, even after adjustment for the number of visits—a finding that does not suggest the existence of discrimination against the poorest.

Women who used private care had a higher number of procedures, and this differential was not explained by maternal characteristics or by attendance patterns.

The present study is aimed at filling a gap in the literature concerning the quality of antenatal care according to type of provider and maternal characteristics. Its strengths included the population-based sample and data collection through standardized questionnaires applied by trained interviewers. However, some methodological difficulties need to be discussed. First, ethnicity is difficult to measure in epidemiological studies (Ford and Kelly 2005), particularly in populations where miscegenation is frequent. Self-assessed maternal skin colour was used as a proxy for ethnic background. During the interview, field workers were also asked to assess maternal skin colour, and the agreement between this measurement and self-report was high (kappa = 0.7). Our results were virtually unchanged when interviewer-rated skin colour was used in the analyses. We opted to use self-report because this approach is widely accepted in Brazilian society, being part of all official publications. Second, information about antenatal care procedures was based on maternal recall because care is provided by over 100 different facilities, and it would not have been feasible to review medical records. When using self-report, it is not possible to ask about specific diagnostic procedures or treatments—for example, we had to inquire about ‘blood tests’ when ideally one would like to have separate information for syphilis and HIV screening, and for haemoglobin levels. Finally, our data are from a single Brazilian city, but overall patterns of health care use are similar to national averages and to other studies showing inequalities in antenatal care in Brazil (Coimbra et al. 2003).

Use of antenatal services was high. The supply of antenatal care in Brazil has improved in recent years. In the mid-1990s, 15% of Brazilian mothers went through pregnancy without any antenatal care, but by 2004 this was true for fewer than 3% of all mothers (SINASC 2005). Similar trends were observed in Pelotas: from 4.9% in 1982 to 1.9% in 2004 (Cesar et al. 2008). Progress can be largely attributed to the creation of the Unified Health System in the late 1980s, when free access to all types of health care was promised to the whole population. There are no user fees for attending governmental health services, and unofficial, so-called ‘under-the-table’, payments for outpatient care are very unusual (Barros and Bertoldi 2008; Barros et al. 2008). Nevertheless, social and ethnic inequalities persist for several health care indicators in Brazil (Comissão Nacional de Determinantes Sociais em Saúde 2008).

Coverage of at least one antenatal care appointment was almost universal, ranging from 96% among the poorest to 99% for the richest. This is consistent with the wide availability of primary health care facilities—about 50 governmental health posts in the urban area, or one per 7000 population, plus scores of private clinics—and their broad distribution throughout the city. Nevertheless, better-off women were more likely to start early and to have a larger number of antenatal visits. Likewise, black women entered prenatal care later and had fewer antenatal consultations than white or brown-colour women. Because there are no user fees, nor other direct out-of-pocket payments in the public sector, these differential patterns are likely related to other types of economic barrier (e.g. transportation costs, or time lost from work), or else to cultural or educational factors that result in poor and black women delaying their first request for antenatal care.

All antenatal procedures analysed in the present study—with the exception of ultrasound—are considered essential components of antenatal care according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health (Ministério da Saúde 2006). The evidence base supporting each of these procedures is variable (Carroli et al. 2001), but the objective of our study is not to describe truly effective interventions, but to assess how currently recommended interventions are reaching different groups of women. Further studies including direct observation of antenatal consultations, rather than maternal report on procedures, will allow investigators to report the frequency of each evidence-based intervention (Carroli et al. 2001), rather than use the broad groupings such as blood or urine analysis that were used in this article. Due to this restriction on the nature of the data collected, it was not possible to limit the analyses to interventions with proven efficacy.

Measurement of blood pressure had almost universal coverage in all socio-economic and ethnic groups. This procedure is routinely carried out by nurses prior to the medical consultation, being repeated at every visit. Large social and ethnic group differences, however, were present for procedures that are carried out by doctors, such as breast and pelvic examination, and screening for cervical cancer. Socio-economic and ethnic group inequalities in clinical breast examination have been described previously in Brazil (Dias-da-Costa et al. 2007) and in Mexico (Couture et al. 2008). We did not find ethnic differences in breastfeeding counselling, although there were important differences in breast examination. In the USA, black women were less likely than whites to report receiving breastfeeding advice during antenatal care (Kogan et al. 1994). Neither socio-economic nor ethnic differences in iron prescription during antenatal care were found in our study, but that was not the case with vitamins. Whereas iron tablets are freely available in government facilities and are inexpensive at private drugstores, multivitamin tablets prescribed for pregnant women are not freely available, costing about U$20 for a monthly prescription. A similar pattern of inequality has been described in the USA (Gavin et al. 2004).

Of particular interest is the frequent use of obstetric ultrasound in all social groups, ranging from 94% among the poorest to 99% among the richest. Ultrasound examinations are not part of the procedures recommended by the Ministry of Health, but are nevertheless provided free of charge by the publicly funded Unified Health System. The almost universal use of ultrasound is in sharp contrast to the very low prescription of vitamins, and each of the four components of physical examination and counselling. In a previous publication we discussed possible reasons for the overuse of medical technologies including caesarean sections and ultrasound examinations (Barros et al. 2005).

Important differences in the quality of antenatal care between public and private facilities were found in the present study. These differences were present within every socio-economic and ethnic group (Figure 1), so that they do not arise from the fact that rich and white women are more likely to attend the private sector. We explored the possibility that these differences could be explained by utilization patterns because private patients had not only a higher number of visits but were also more likely to start antenatal care in the first trimester than women attending the public sector. However, even after adjustment for these differences, antenatal care quality was still higher in the private than in the public sector. As in most high- and middle-income countries, the private sector in Brazil is used by families who are able to afford private health insurance or to make out-of-pocket payments; in our study 58% of women in the top quintile used the private sector compared with only 6% in the poorest quintile. Private clinics tend to have better installations and longer consultation times than those in the public sector, and private doctors receive better pay. Therefore, it is not surprising that a larger number of recommended procedures are carried out in the private sector, a finding that has also been reported in South Africa for cervical cancer screening (Bailie et al. 1996). However, our findings cannot be extrapolated to low-income countries because in these settings the private sector is largely made up by informal, unregulated and unqualified providers catering mostly for the poorest strata of the population (Mills et al. 2002).

Health care is just one domain in which unequal treatment of the poor and of ethnic minorities is known to occur. Socio-economic as well as ethnic discrimination are present in other domains, such as education, labour markets, the criminal justice system and political participation (Heringer 2002). However, in the present study, there was no quantitative evidence of overt discrimination against the poor by health workers, either in the public or in the private health sector. Nevertheless, the poor and black women and their babies show worse outcomes than the rest of the population (Matijasevich et al. 2008), which could reflect the presence of other social, environmental or nutritional disadvantages, rather than differential antenatal treatment.

In terms of policy implications, our findings suggest the need for investing in the demand and supply sides. Women, particularly those in the socially disadvantaged groups, should be encouraged to start antenatal care early in pregnancy so that they can benefit fully from it. And the quality of care, particularly in the public sector, has to be improved. Most of the procedures included in the present analyses could have been delivered in a single visit, so that even women who failed to attend more than once would be covered. Finally, there is a need for regular monitoring of antenatal attendances and quality of care with an equity lens, in order to assess how different social groups are benefiting from the progress of health care.

Funding

These analyses were specifically funded by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Council (CNPq) grant entitled: ‘Socioeconomic & racial/ethnic inequalities in maternal and child health’.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in the 2004 Pelotas cohort study, and the whole Pelotas cohort team, including interviewers, data clerks and volunteers. The 2004 Pelotas cohort study was financed by the Division of Child and Adolescent Health and Development of the World Health Organization, by the “Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico”, Brazil, and by the “Pastoral da Criança” (Catholic non-governmental organization, Curitiba, Brazil). The Wellcome Trust currently provides support for the 2004 Pelotas cohort study.

References

- ACOG–Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. ACOG committee opinion. Number 317, October 2005. Racial and ethnic disparities in women’s health. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;106:889–92. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200510000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida SD, Barros MB. Equity and access to health care for pregnant women in Campinas (SP), Brazil. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica. 2005;17:15–25. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailie RS, Selvey CE, Bourne D, et al. Trends in cervical cancer mortality in South Africa. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;25:488–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros AJ, Bertoldi AD. Out-of-pocket health expenditure in a population covered by the Family Health Program in Brazil. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37:758–65. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros FC, Victora CG. Iniqüidades em saúde de crianças menores de cinco anos no Brasil. Uma revisão sistemática da literatura, 1990–2007. Rio de Janeiro: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barros FC, Victora CG, Horta BL. Ethnicity and infant health in Southern Brazil: a birth cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:1001–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros FC, Victora CG, Barros AJ, et al. The challenge of reducing neonatal mortality in middle-income countries: findings from three Brazilian birth cohorts in 1982, 1993 and 2004. The Lancet. 2005;365:847–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros AJ, Da Silva Dos Santos I, Victora CG, et al. [The 2004 Pelotas birth cohort: methods and description] Revista de Saude Publica. 2006;40:402–13. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros AJ, Santos IS, Bertoldi AD. Can mothers rely on the Brazilian health system for their deliveries? An assessment of use of the public system and out-of-pocket expenditure in the 2004 Pelotas Birth Cohort Study, Brazil. BMC Health Service Research. 2008;8:57. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt JR, Maina AW. The Institute of Medicine report 'Unequal Treatment': implications for academic health centers. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2004;71:314–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerma JT, Bryce J, Kinfu Y, Axelson H, Victora CG. Mind the gap: equity and trends in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health services in 54 Countdown countries. The Lancet. 2008;371:1259–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojalil R, Kirkwood BR, Bobak M, Guiscafre H. The relative contribution of case management and inadequate care-seeking behaviour to childhood deaths from diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections in Hidalgo, Mexico. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2007;12:1545–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J. How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? An overview of the evidence. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2001;15(Suppl 1):1–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.0150s1001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesar JA, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, et al. The use of maternal and child health services in three population-based cohorts in Southern Brazil, 1982-2004. Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2008;24:S427–36. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008001500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra L C, Silva AA, Mochel EG, et al. [Factors associated with inadequacy of prenatal care utilization] Revista de Saude Publica. 2003;37:456–62. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102003000400010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comissão Nacional de Determinantes Sociais em Saúde. As Causas Sociais das Iniqüidades em Saúde no Brasil: Relatório Final. [National Commission on Social Determinants of Health. The Social Causes of Health Inequities in Brazil] Rio de Janeiro: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Couture MC, Nguyen CT, Alvarado BE, et al. Inequalities in breast and cervical cancer screening among urban Mexican women. Preventive Medicine. 2008;47:471–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias-Da-Costa JS, Olinto MT, Bassani D, et al. [Inequalities in clinical breast examination in Sao Leopoldo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil] Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2007;23:1603–12. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007000700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ME, Kelly PA. Conceptualizing and categorizing race and ethnicity in health services research. Health Service Research. 2005;40:1658–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Adams EK, Hartmann KE, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of pregnancy-related health care among Medicaid pregnant women. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2004;8:113–26. doi: 10.1023/b:maci.0000037645.63379.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin DR, Bhuiya A, Victora C, et al. Making health systems more equitable. The Lancet. 2004;364:1273–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin DR, Rutstein S, Johnson K, et al. Socioeconomic differences in health, nutrition, and population. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heringer R. [Racial inequalities in Brazil: a synthesis of social indicators and challenges for public policies] Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2002;18(Suppl):57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessner DM, Singer J, Kalk CE, et al. Contrasts in Health Status Vol. 1: Infant death: an analysis by maternal risk and health care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan MD, Kotelchuck M, Alexander GR, Johnson WE. Racial disparities in reported prenatal care advice from health care providers. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:82–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon ZR, Lackan N. Ethnic disparities in access to care in post-apartheid South Africa. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:2272–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelchuck M. An evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a proposed Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1414–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal MC, Gama SG, Ratto KM, Cunha CB. Use of the modified Kotelchuck index in the evaluation of prenatal care and its relationship to maternal characteristics and birth weight in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Publica. 2004;20(Suppl. 1):S63–72. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2004000700007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44:757–71. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matijasevich A, Victora CG, Barros AJ, et al. Widening ethnic disparities in infant mortality in southern Brazil: comparison of 3 birth cohorts. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:692–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A, Brugha R, Hanson K, McPake B. What can be done about the private health sector in low-income countries? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2002;80:325–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde . Pré-natal e puerpério—Atenção qualificada e humanizada—Manual técnico. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- PPHCKN . Inequities in the health and nutrition of children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Report of the Priority Public Health Conditions Knowledge Network of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Puccini RF, Pedroso GC, Silva EMK, Araújo NS, Silva NN. Equidade na atenção pré-natal e ao parto em área da Região Metropolitana de São Paulo, 1996. Cadernos de Saúde Publica. 2003;19:35–45. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos IS, Uga MA, Porto SM. [The public-private mix in the Brazilian Health System: financing, delivery and utilization of health services] Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2008;13:1431–40. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232008000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINASC . Consultas pré-natal. 2005. Brasil Ministério da Saúde, Sistema De Informações Sobre Nascidos Vivos (SINASC) Online at: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sinasc/cnv/nvuf.def, accessed 18 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Victora CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA, et al. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. The Lancet. 2003;362:233–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13917-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Racial/ethnic variations in women’s health: the social embeddedness of health. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:588–97. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]