Abstract

Background

The randomized EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS trial investigates whether breast cancer patients with a tumor-positive sentinel node biopsy (SNB) are best treated with an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) or axillary radiotherapy (ART). The aim of the current substudy was to evaluate the identification rate and the nodal involvement.

Methods

The first 2,000 patients participating in the AMAROS trial were evaluated. Associations between the identification rate and technical, patient-, and tumor-related factors were evaluated. The outcome of the SNB procedure and potential further nodal involvement was assessed.

Results

In 65 patients, the sentinel node could not be identified. As a result, the sentinel node identification rate was 97% (1,888 of 1,953). Variables affecting the success rate were age, pathological tumor size, histology, year of accrual, and method of detection. The SNB results of 65% of the patients (n = 1,220) were negative and the patients underwent no further axillary treatment. The SNB results were positive in 34% of the patients (n = 647), including macrometastases (n = 409, 63%), micrometastases (n = 161, 25%), and isolated tumor cells (n = 77, 12%). Further nodal involvement in patients with macrometastases, micrometastases, and isolated tumor cells undergoing an ALND was 41, 18, and 18%, respectively.

Conclusions

With a 97% detection rate in this prospective international multicenter study, the SNB procedure is highly effective, especially when the combined method is used. Further nodal involvement in patients with micrometastases and isolated tumor cells in the sentinel node was similar—both were 18%.

The concept of sentinel node biopsy (SNB) is based on an orderly pattern of lymphatic drainage from the primary tumor to regional lymph node basins.1 The first lymph node to which a tumor drains, the sentinel node, is detected with the aid of blue dye and/or a radioactive tracer and subsequently removed. The pathological status of the sentinel node is used to decide whether an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) should be performed. Patients with a tumor-negative sentinel node can be spared a completion ALND and the associated side effects. In 1994, Giuliano et al. first reported the SNB procedure in breast cancer.2 The SNB procedure was followed by routine ALND in the learning phase. In this period, the median false-negative rate of the SNB procedure was 7%.3 At present, the sentinel node procedure is the standard treatment in patients with a clinically negative axilla. The axillary recurrence rate in patients with a negative sentinel node is low, 0.3% after a median of 34 months.4 Nevertheless, whether omitting an ALND in patients with tumor-negative sentinel nodes will affect the survival is still subject of research in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-32 trial.5

Patients with a tumor-positive sentinel node are generally treated with an ALND. Severe side effects of ALND include lymph edema and decreased arm and shoulder function and are observed in 5% to 39% of the patients after axillary clearance.6–8 In 2001, the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) initiated a trial to evaluate the role of axillary radiation. The EORTC 10981 AMAROS (After Mapping of the Axilla, Radiotherapy or Surgery?) trial is a phase III study comparing ALND with axillary radiotherapy (ART) in patients with a tumor-positive sentinel node.9 The main objective of the trial is to prove equivalent locoregional control and reduced morbidity for ART. A secondary aim is to assess the survival in patients with tumor-negative sentinel node without additional axillary clearance. Therefore, patients with a tumor-negative sentinel node are also included in the AMAROS trial. The AMAROS trial is ongoing. The accrual of the required 4,767 patients is expected to be finalized in the year 2010.

The aim of the current substudy was to analyze the technical aspects and outcome of the SNB procedure in the first 2,000 patients, mainly to control for validity of future trial results. We analyzed the identification rate of the SNB procedure and the association between the identification rate and several technical, clinical, and pathological variables. With regard to the outcome of the SNB procedure, research was focused on the relation between the size of the sentinel node metastases and the further nodal involvement.

Patients and Methods

After obtaining permission from the EORTC Independent Data Monitoring Committee, the first 2,000 patients with operable unifocal invasive breast cancer (5–30 mm) and clinically negative lymph nodes enrolled onto the AMAROS trial were analyzed. The study design of the AMAROS trial is shown in Fig. 1. Patients were not admitted to the AMAROS trial if any of the following criteria were present: (1) metastatic disease, (2) previous treatment of the axilla by surgery or radiotherapy, (3) previous treatment of cancer, except basal-cell carcinoma of the skin and in-situ carcinoma of the cervix, or (4) pregnancy. Between 2001 and 2005, a total of 2,000 patients were entered in the AMAROS trial from 26 institutions in Europe. All institutions have been site visited as part of the surgical quality assurance.

Fig. 1.

Study design. Patients with clinically negative lymph nodes and tumors of <3 cm are randomized between ALND and axillary radiotherapy before the sentinel node biopsy procedure. In sentinel node–negative patients, no further axillary treatment is provided

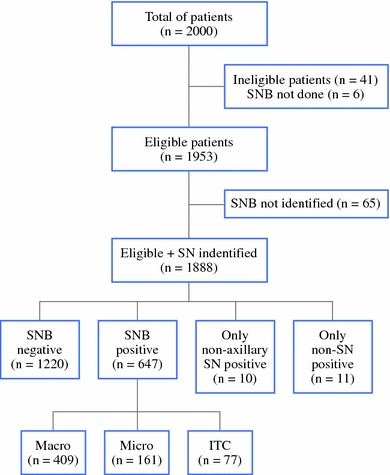

Before the SNB procedure, patients were randomized between ALND and ART. This allowed the application of breast surgery and axillary surgery simultaneously when positive sentinel nodes were found by frozen section. Of the first 2,000 patients, 41 patients were ineligible as a result of patient refusal or because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and in 6 patients, the SNB procedure was not performed (Fig. 2). Hence, 1,953 patients were eligible for this substudy, and data from these patients form the body of this report. Randomization was accomplished centrally by the EORTC headquarters, and patients were stratified according to institution. The AMAROS trial was approved by the institutional ethical committees, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. The indications to offer systemic therapy were not fixed in the protocol. The actual chemotherapies and endocrine therapies were provided according to local guidelines.

Fig. 2.

Patient flow in the EORTC AMAROS trial regarding the identification and results of the SNB procedure. SN sentinel node; Macro macrometastases (>2 mm); Micro micrometastases (0.2–2 mm); ITC isolated tumor cells (<0.2 mm)

Surgery

All participating surgeons had to have previously performed a minimum of 30 prequalifying cases of the SNB procedure for breast cancer before being allowed to participate in the trial. In 1,744 patients, the SNB procedure was performed by the combined method of blue dye and isotope with intraoperatively detection with a gamma probe. A minority of SNB procedures were performed with isotope (n = 181) or blue dye (n = 19) only. Lymphoscintigrams were recommended, although not mandatory. Radioactive and blue-stained nodes were removed, and if present, nonsentinel nodes that were suspicious for metastatic cancer on palpation but that were not radioactive or blue were also removed. Subsequently, mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery was carried out. Patients with tumor-positive sentinel nodes who were allocated to the ALND arm underwent a level I and II ALND within 12 weeks. In that case, removal of at least eight lymph nodes was mandatory.

Radiotherapy

Sentinel node–positive patients allocated to the ART arm were irradiated within 12 weeks after surgery. All three levels of the axilla together with the medial part of the supraclavicular fossa were considered clinical the target volume. The prescribed dose to the axilla as a whole was 50 Gy in 25 fractions of 2 Gy in 5 weeks. All institutions documented their techniques for axillary irradiation on a dummy run that was evaluated by the radiotherapy quality assurance team before their participation was allowed.10 Postoperative axillary irradiation in patients undergoing ALND was allowed in patients with four or more tumor-positive nodes (pN2 or pN3) and was applied according to institutional protocols.

Pathology

As a minimal requirement, three histological levels (500-μm distance) for each sentinel node were examined. On each level, two parallel sections were performed, one for immunohistochemistry and one for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Immunohistochemical staining was performed for markers containing at least cytokeratin 8 and 18 (e.g., CAM 5.2). Immunohistochemical staining was required only when hematoxylin and eosin staining was negative. The sentinel node was considered tumor positive if any tumor deposit in the node or in the afferent or efferent lymph vessels was found. Tumor deposits were categorized as isolated tumor cells (<0.2 mm), micrometastases (0.2–2 mm), or macrometastases (>2 mm).

Statistical Analysis

Associations between the identification rate and patient and tumor related factors were evaluated by Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (χ2) type tests for overall association. All P values were two tailed, with P = 0.05 or lower considered significant.

Results

The patient and tumor characteristics of the 1,953 eligible patients in whom a SNB procedure was performed are shown in Table 1. The median age was 57 years (range 24–87 years), and most patients had ductal invasive carcinoma. The tumor size at pathology was mostly <20 mm; pT1 and pT2 tumors were seen in 74 and 24%, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics of eligible patients (n = 1,953)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | |

| Median | 57 |

| Range | 24–87 |

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |

| Premenopausal | 543 (28%) |

| Perimenopausal | 113 (6%) |

| Postmenopausal | 1,193 (61%) |

| Unknown | 104 (5%) |

| Pathological tumor size, n (%) | |

| T1 | 1,454 (74%) |

| T2 | 465 (24%) |

| T3 | 13 (1%) |

| Missing | 21 (1%) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| Ductal | 1,416 (73%) |

| Lobular | 220 (11%) |

| Other | 304 (16%) |

| Missing | 13 (1%) |

| Grade, n (%) | |

| I | 548 (28%) |

| II | 842 (43%) |

| III | 493 (25%) |

| Missing | 70 (4%) |

Identification Rate

In 65 patients, the sentinel node could not be identified. Thus, the sentinel node identification rate was 97% (1,888 of 1,953). Variables affecting the success rate were age, pathological tumor size, histology, year of accrual, and method of detection (Table 2). The success rate was higher in younger patients. In patients with pT3 tumors, the identification rate was lower compared to patients with pT1 tumors. In patients with lobular and ductal carcinomas, the success rate was high compared to other types of histology such as tubular and mixed ductolobular carcinomas. The identification rate increased within the time period of the study, although the detection was high in the first year of the study. With the combination of blue dye and radioactive tracers, a higher identification rate was achieved compared to one of these tracers only. In case of nonvisualization by lymphoscintigraphy, 77% of the SNB procedures were still performed successfully.

Table 2.

Variables affecting the SNB identification rate

| Variable | Not identified (n = 65), n (%) | Identified (n = 1,888), n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 0.002 | ||

| <30 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | |

| 30–49 | 9 (2) | 481 (98) | |

| 50–69 | 37 (3) | 1,163 (97) | |

| ≥70 | 19 (7) | 239 (93) | |

| Pathological tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | ||

| ≤1 | 14 (3) | 411 (97) | |

| 1–2 | 30 (3) | 999 (97) | |

| 2–3 | 6 (2) | 401 (98) | |

| 3–5 | 3 (5) | 55 (95) | |

| >5 | 3 (23) | 10 (77) | |

| Histology | 0.009 | ||

| Invasive ductal | 38 (3) | 1,378 (97) | |

| Invasive lobular | 2 (1) | 218 (99) | |

| Other | 16 (5) | 288 (95) | |

| Year of accrual | 0.043 | ||

| 2001 | 2 (1) | 151 (99) | |

| 2002 | 20 (6) | 325 (94) | |

| 2003 | 12 (3) | 467 (97) | |

| 2004 | 19 (3) | 530 (97) | |

| 2005 | 12 (3) | 415 (97) | |

| Method SNB | <0.001 | ||

| Blue dye only | 2 (11) | 17 (90) | |

| Radioactive tracer only | 18 (10) | 163 (90) | |

| Blue dye and radioactive tracer | 36 (2) | 1,708 (98) | |

| Lymphoscintigram | NA | ||

| Nonvisualization | 29 (23) | 99 (77) |

SNB sentinal node biopsy; NA not applicable; NS not significant

Drainage to the internal mammary chain was observed in 11% of the patients (198 of 1,778) (Fig. 3). The treatment of the internal mammary chain differed by institution. In half of the patients with drainage to the internal mammary chain, these nodes were removed.

Fig. 3.

Drainage to the internal mammary chain seen on lymphoscintigraphy and the subsequent surgical removal. IMC internal mammary chain

Outcome of Sentinel Node Procedure

Sixty-five percent of patients (n = 1,220) were sentinel node negative and underwent no further axillary treatment. The sentinel node was positive in 34% (n = 647). In this group, 409 patients (63%) had macrometastases, 161 patients (25%) had micrometastases, and 77 patients (12%) had isolated tumor cells. Ten patients (0.5%) had positive sentinel nodes only in an extra-axillary region, i.e., internal mammary chain or supraclavicular. In these patients, no further axillary treatment was performed. In 357 (19%) of 1,888 patients, nonsentinel nodes were removed (nonblue or nonradioactive lymph nodes) during the SNB procedure. These nonsentinel nodes were tumor positive in 12% (n = 44). Predictive variables for tumor-positive nonsentinel nodes were tumor size (P < 0.001) and tumor grade (P < 0.001). Nonsentinel nodes were more frequently tumor positive in large and high-grade tumors. In 11 patients (3%), these nonsentinel nodes were the only tumor-positive sentinel nodes. Four of these patients had lack of drainage seen on preoperative lymphoscintigraphy. These SNB procedures can actually be considered falsely negative. Because axillary clearance is omitted in sentinel node–negative patients, the actual false-negative rate in this study will remain unknown.

We did not separately collect data about the outcome of the sentinel nodes in the internal mammary chain in patients in whom these were removed.

Further Nodal Involvement

The further nodal involvement could only be determined in the group of patients randomized to the ALND arm (Table 3). Forty-one percent of the patients with macrometastases had additional nodal involvement. Further nodal involvement was 18% in both the patients with micrometastases and the patients with isolated tumor cells. More than four additional lymph nodes were tumor positive in the patients with macrometastases, micrometastases, and isolated tumor cells in 9, 6, and 3%, respectively. In the patients with micrometastases or isolated tumor cells in the sentinel node and more than four tumor-positive additional lymph nodes, these consisted of more than four macrometastases in all patients except one.

Table 3.

Further nodal involvement in ALND specimena

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Macro (n = 200) | ||

| No further involvement | 117 | 59 |

| 1–3 nodes | 65 | 32 |

| 4–9 nodes | 10 | 5 |

| >9 nodes | 8 | 4 |

| Micro (n = 84) | ||

| No further involvement | 69 | 82 |

| 1–3 nodes | 10 | 12 |

| 4–9 nodes | 3 | 4 |

| >9 nodes | 2 | 2 |

| ITC (n = 33) | ||

| No further involvement | 27 | 82 |

| 1–3 nodes | 5 | 15 |

| 4–9 nodes | 1 | 3 |

| >9 nodes | 0 | 0 |

aFurther nodal involvement shown in correlation with the size of the sentinel node metastases in the patients randomized to ALND arm. ALND axillary lymph node dissection; Macro macrometastases (>2 mm); Micro micrometastases (0.2–2 mm); ITC isolated tumor cells (<0.2 mm)

Discussion

In this prospective multicenter study, the sentinel node identification rate was 97%. Lymphatic mapping with the sentinel node procedure was first reported in breast cancer in 1994 and is therefore a relatively young procedure. The patients described in this study were included in the period from 2001 and 2004, and were thus in the relatively early days of the general introduction of this procedure. Nevertheless, the success rate was high. The identification rate was influenced by several variables that we will discuss separately.

The reduced identification rate in older patients is consistently reported.11–13 The increased fatty tissue in the breast in elderly patients might cause an decreased lymphatic flow.14 It is also suggested that the replacement of lymph nodes by fatty tissue decreases the capacity of lymph nodes to retain the radioactive colloid.15

Tumor size was also associated with the detection rate, showing a low identification rate in tumors >5 cm in size. It must be noted that only 13 patients in this study had tumors of >5 cm. Patients with large tumors have a greater risk of extensive axillary tumor burden, which decreases the lymphoscintigraphic visualization.16,17 Patients with more than four tumor-positive lymph nodes have nonvisualization in >50%.18 Performance of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration before the SNB procedure will identify at least some of these patients and thus increase the identification rate.

In this study, the identification rate was slightly lower in patients with other than ductal and lobular carcinomas. This group includes mainly tubular, mucinous, and mixed ductolobular tumors. Because of the heterogeneity of this group, this finding is difficult to explain. Others have not found a correlation with histology.19,20

The association between method of detection and the sentinel node identification is notable, showing a higher detection rate with the combined method (radioactive tracer and blue dye). With blue dye, the lymphatic channel can be identified until it enters and stains the first node. The value of the gamma detection probe is that the location of the node can be determined through the intact skin, and the sentinel can be identified once the lymphatic channel is accidentally damaged. Relying on the gamma detection probe only and omitting blue dye leads to a situation where relevant nodes are left behind, because 5–17% of the sentinel nodes are only blue.5,21,22 Some investigators, however, still use only one of the detection methods. On the basis of our results, which have been confirmed by others, we recommend the use of the combined method.3,11,13

The year of accrual also influenced the identification rate and reflected a learning curve, although surgeons participating in this trial were past their learning period of 30 SNB procedures with a completion axillary clearance. Remarkably, the detection rate was lowest in 2002 and not at the start of the study in 2001. This might be explained by the relatively high number of patients accrued by highly experienced academic institutes at the beginning of the AMAROS trial.

In this study, lymphoscintigraphy did not visualize sentinel nodes in a small number of patients. Despite the nonvisualization, the sentinel node could still be identified in 77% of these patients, particularly by blue dye. This suggests that SNB procedure ought to be pursued in these patients, and that nonvisualization is not an absolute indication for ALND.

Finally, we observed that in 3% of the patients in whom nonsentinel nodes were removed, these nonsentinel nodes were the only tumor-positive nodes. In these patients, the SNB procedure can be considered as falsely negative. Extensive tumor burden may obstruct the lymph flow and thus lead to falsely negative sentinel nodes. This finding emphasizes the importance of palpation after removing the sentinel node. The false-negative rate could also be diminished by performing preoperative axillary ultrasound.

In the patient population of the AMAROS trial—that is, patients with a clinically negative axilla and breast tumor of <3 cm—34% of the patients had a tumor-positive sentinel node. Isolated tumor cells within the sentinel node were classified as having node-positive disease at this time, according to the previous edition (5th edition) of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual.23 Yet in the current substudy of this prospective clinical trial, we were able to assess the further nodal involvement in macrometastases, micrometastases, and isolated tumor cells separately. Further nodal involvement was seen in 18% of the patients with both micrometastases (15 of 84) and isolated tumor cells (6 of 33), whereas extensive nodal involvement was slightly higher in patients with micrometastases. In the current staging classification systems, isolated tumor cells are classified as node-negative (pN0(i+)) disease.24,25 Since 2008, in the AMAROS trial, isolated tumor cells are also considered to be sentinel node negative and do not require further axillary treatment.

In the most recent meta-analysis, the overall pooled risk for additional nodal involvement in patients with isolated tumors cells was 12.3% (95% confidence interval 9.5–15.7).26 Omitting ALND is probably acceptable for most patients whose sentinel node contains isolated tumor cells, especially given a marginally lower false-negative rate of 7% of the SNB procedure.3 Additional microscopic axillary metastases might be eradicated by adjuvant radiotherapy to the breast, including the caudal half of the axilla, or by adjuvant chemotherapy or endocrine therapy. These hypotheses are reflected by a low axillary recurrence rate in sentinel node–positive patients treated with a SNB procedure only (i.e., without axillary clearance).27–32

The retrospective Dutch MIRROR trial recently showed that omission of further axillary treatment in patients with micrometastases resulted in a far higher 5-year axillary recurrence rate (1.2 vs. 6.2%, hazard ratio 4.45; 95% confidence interval 1.46–13.54).33 The International Breast Cancer Study Group trial IBCSG-23-01 is currently addressing whether differences in survival exist between patients with micrometastases who have a SNB procedure compared with ALND.34 However, the size of the sentinel node metastases is not the only predictor for further nodal involvement. Increased tumor size, more than one positive sentinel lymph node, lymphovascular invasion in the primary tumor, and lobular histology also have statistically significant predictive value.35 Several nomograms and models including these variables have been established to estimate the risk of further nodal involvement and might be used to select those patients with micrometastases and isolated tumor cells who may benefit from axillary treatment and those who can be safely spared axillary clearance.36 Further studies addressing which patients with microscopic metastases in the sentinel node can be safely withhold axillary treatment are warranted.

In conclusion, this study indicates that with a 97% detection rate in this prospective international multicenter study the sentinel node procedure is highly effective. The success rate is influenced by the method of the SNB procedure and by several patient and tumor characteristics. In patients with micrometastases and isolated tumor cells in the sentinel node, further nodal involvement was low (18%) but not negligible. The final analysis of the AMAROS trial will show whether patients with a tumor-positive sentinel node will be adequately treated with ART compared to ALND in terms of axillary control and arm and shoulder morbidity.

Acknowledgment

This publication was supported by grants 2U10 CA11488-28 through 5U10 CA011488-38 from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD) and by a donation from the Kankerbestrijding/KWF from the Netherlands through the EORTC Charitable Trust. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Cancer Institute. We are indebted to the women who participated in this study and to the doctors, nurses, and data managers from the participating hospitals in the Europe who enrolled patients onto the AMAROS trial.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Principal and Coinvestigators of the AMAROS Trial

The following clinicians entered patients onto the study, participated in the study, or both (number of accrued patients is in parentheses): The Netherlands; W. Bouma, Gelre Hospital, Apeldoorn (144); P. de Graaf, Reinier de Graaf Hospital, Delft (85); G. Nieuwenhuyzen and M. van der Sangen, Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven (114); J. Merkus Rode Kruis Hospital, Den Haag (39), E.Rutgers and N. Russell, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Amsterdam (267), M. Albregts and T. van Dalen, UMCU and Diakonessen Hospital, Utrecht (13), C. van de Velde, LUMC, Leiden (59); A. Marinelli and H. Struikmans, Medisch Centrum Haaglanden (38); O. Guicherit, Bronovo Hospital, Den Haag (11); H.Rijna Kennemer Gasthuis, Haarlem (39); W.Steup, Leyenburg Hospital, Den Haag (1); J. de Vries, UMCG, Groningen (19); J. Debet, Laurentius Hospital, Roermond (28); G.van Tienhoven and B. Kluit, AMC, Amsterdam (62), R. Tobon Morales, St. Jansdal Hospital, Harderwijk and H. Westenberg Institute for Radiation Oncology, Arnhem (46), J. Klinkenbijl, Rijnstate Hospital, and H. Westenberg, Institute for Radiation Oncology, Arnhem (228); H. van der Mijle, Nijsmellinghe, Drachten (198), S. Veltkamp, Amstelveen Hospital, Amstelveen (114); France: M. Bolla, CHU de Grenoble (19); Y. Belkacemi, Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille (43); Switzerland: M. Kohlik, Hopital Cantonal Universitaire Geneve, Geneve (2); Poland: J. Jassem and J Jaskiewicz, medical university of Gdansk, Gdansk (2); Italy: M. Mano, Ospedale San Giovanni Antica Seda, Torino (52), L. Cataliotti, Universita Degli Studi di Firenze (293); Slovenia: M. Snoj, Insitute of Oncology, Ljubljana (82), Israel: H. Goldberg, Rambam Medical Center, Haifa (2).

Contributor Information

Marieke E. Straver, Email: m.straver@nki.nl.

Emiel J. T. Rutgers, Email: e.rutgers@nki.nl.

References

- 1.Braithwaite LR. The flow of lymph from the ileocaecal angle, and its possible bearing on the cause of duodenal and gastric ulcer. Br J Surg. 1923;11:7–26. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800114103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, Morton DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220:391–398. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nieweg OE, Jansen L, Valdes Olmos RA, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:S11–S16. doi: 10.1007/s002590050572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Ploeg IM, Nieweg OE, van Rijk MC, Valdes Olmos RA, Kroon BB. Axillary recurrence after a tumour-negative sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1277–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Technical outcomes of sentinel-lymph-node resection and conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: results from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:881–888. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dabakuyo TS, Fraisse J, Causeret S, et al. A multicenter cohort study to compare quality of life in breast cancer patients according to sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1352–1361. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:599–609. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrek JA, Heelan MC. Incidence of breast carcinoma-related lymphedema. Cancer. 1998;83:2776–2781. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981215)83:12B+<2776::AID-CNCR25>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutgers EJ, Meijnen P, Bonnefoi H. Clinical trials update of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Group. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:165–169. doi: 10.1186/bcr906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurkmans CW, Borger JH, Rutgers EJ, van Tienhoven G. Quality assurance of axillary radiotherapy in the EORTC AMAROS trial 10981/22023: the dummy run. Radiother Oncol. 2003;68:233–240. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(03)00194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMasters KM, Tuttle TM, Carlson DJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer: a suitable alternative to routine axillary dissection in multi-institutional practice when optimal technique is used. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2560–2566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakera AH, Friis E, Hesse U, et al. Factors of importance for scintigraphic non-visualisation of sentinel nodes in breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:286–293. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1681-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chagpar AB, Martin RC, Scoggins CR, et al. Factors predicting failure to identify a sentinel lymph node in breast cancer. Surgery. 2005;138:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox CE, Dupont E, Whitehead GF, et al. Age and body mass index may increase the chance of failure in sentinel lymph node biopsy for women with breast cancer. Breast J. 2002;8:88–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krag D, Weaver D, Ashikaga T, et al. The sentinel node in breast cancer—a multicenter validation study. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:941–946. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanis PJ, van Sandick JW, Nieweg OE, et al. The hidden sentinel node in breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:305–311. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0732-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong SL, Edwards MJ, Chao C, Simpson D, McMasters KM. The effect of lymphatic tumor burden on sentinel lymph node biopsy results. Breast J. 2002;8:192–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenot-Rossi I, Houvenaeghel G, Jacquemier J, et al. Nonvisualization of axillary sentinel node during lymphoscintigraphy: is there a pathologic significance in breast cancer? J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1232–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posther KE, McCall LM, Blumencranz PW, et al. Sentinel node skills verification and surgeon performance: data from a multicenter clinical trial for early-stage breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:593–599. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000184210.68646.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelosi E, Ala A, Bello M, et al. Impact of axillary nodal metastases on lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node identification rate in patients with early stage breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:937–942. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1797-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox CE, Pendas S, Cox JM, et al. Guidelines for sentinel node biopsy and lymphatic mapping of patients with breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;227:645–651. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199805000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doting MH, Jansen L, Nieweg OE, et al. Lymphatic mapping with intralesional tracer administration in breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2000;88:2546–2552. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11<2546::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE. American Joint Committee on cancer staging manual. 5th ed. Philidelphia: Lippencott-Raven; 1997.

- 24.Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch. International Union Against Cancer. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 6th ed. New York: Wiley; 2008.

- 25.Green FL, Page DL, Fleming ID. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Deurzen CH, de Boer M, Monninkhof EM, et al. Non-sentinel lymph node metastases associated with isolated breast cancer cells in the sentinel node. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1574–1580. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fant JS, Grant MD, Knox SM, et al. Preliminary outcome analysis in patients with breast cancer and a positive sentinel lymph node who declined axillary dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:126–130. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guenther JM, Hansen NM, DiFronzo LA, et al. Axillary dissection is not required for all patients with breast cancer and positive sentinel nodes. Arch Surg. 2003;138:52–56. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang RF, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Yi M, et al. Low locoregional failure rates in selected breast cancer patients with tumor-positive sentinel lymph nodes who do not undergo completion axillary dissection. Cancer. 2007;110:723–730. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeruss JS, Winchester DJ, Sener SF, et al. Axillary recurrence after sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:34–40. doi: 10.1007/s10434-004-1164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langer I, Marti WR, Guller U, et al. Axillary recurrence rate in breast cancer patients with negative sentinel lymph node (SLN) or SLN micrometastases: prospective analysis of 150 patients after SLN biopsy. Ann Surg. 2005;241:152–158. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000149305.23322.3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naik AM, Fey J, Gemignani M, et al. The risk of axillary relapse after sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer is comparable with that of axillary lymph node dissection: a follow-up study of 4008 procedures. Ann Surg. 2004;240:462–468. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000137130.23530.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tjan-Heijnen VC, Pepels MJ, De Boer G, et al. Impact of omission of completion axillary lymph node dissection (cALND) or axillary radiotherapy (ax RT) in breast cancer patients with micrometastases (pN1mi) or isolated tumor cells (pN0[i+]) in the sentinel lymph node (SN): results from the MIRROR study. 2009;27:18S.

- 34.Galimberti V. International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial of sentinel node biopsy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:210–211. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Zee KJ, Manasseh DM, Bevilacqua JL, et al. A nomogram for predicting the likelihood of additional nodal metastases in breast cancer patients with a positive sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:1140–1151. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coutant C, Olivier C, Lambaudie E, et al. Comparison of models to predict nonsentinel lymph node status in breast cancer patients with metastatic sentinel lymph nodes: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2800–2808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]