Abstract

Pepper, Capsicum spp., is a worldwide crop valued for heat, nutrition, and rich pigment content. Carotenoids, the largest group of plant pigments, function as antioxidants and as vitamin A precursors. The most abundant carotenoids in ripe pepper fruits are β-carotene, capsanthin, and capsorubin. In this study, the carotenoid composition of orange fruited Capsicum lines was defined along with the allelic variability of the biosynthetic enzymes. The carotenoid chemical profiles present in seven orange pepper varieties were determined using a novel UPLC method. The orange appearance of the fruit was due either to the accumulation of β-carotene, or in two cases, due to only the accumulation of red and yellow carotenoids. Four carotenoid biosynthetic genes, Psy, Lcyb, CrtZ-2, and Ccs were cloned and sequenced from these cultivars. This data tested the hypothesis that different alleles for specific carotenoid biosynthetic enzymes are associated with specific carotenoid profiles in orange peppers. While the coding regions within Psy and CrtZ-2 did not change in any of the lines, the genomic sequence contained introns not previously reported. Lcyb and Ccs contained no introns but did exhibit polymorphisms resulting in amino acid changes; a new Ccs variant was found. When selectively breeding for high provitamin A levels, phenotypic recurrent selection based on fruit color is not sufficient, carotenoid chemical composition should also be conducted. Based on these results, specific alleles are candidate molecular markers for selection of orange pepper lines with high β-carotene and therefore high pro-vitamin A levels.

Keywords: fruit pigmentation, carotenes, xanthophylls, capsanthin, capsorubin

1. Introduction

Colored vegetables can contribute required and recommended amounts of carotenoids that are important antioxidants or provitamin A compounds in the human diet. According to the World Health Organization, vitamin A deficiency is a public health problem causing blindness in an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 children per year [1]. High β-carotene peppers, Capsicum spp., could be a solution in the battle to fight vitamin A deficiency. Humans are able to convert some provitamin A carotenoids like β-carotene into vitamin A using intestinal mono-oxygenases; 6 µg of β-carotene are converted to 1 µg of retinol (vitamin A) [2]. In addition, β-carotene is an efficient radical scavenger quenching free radicals before they damage cells [3,4].

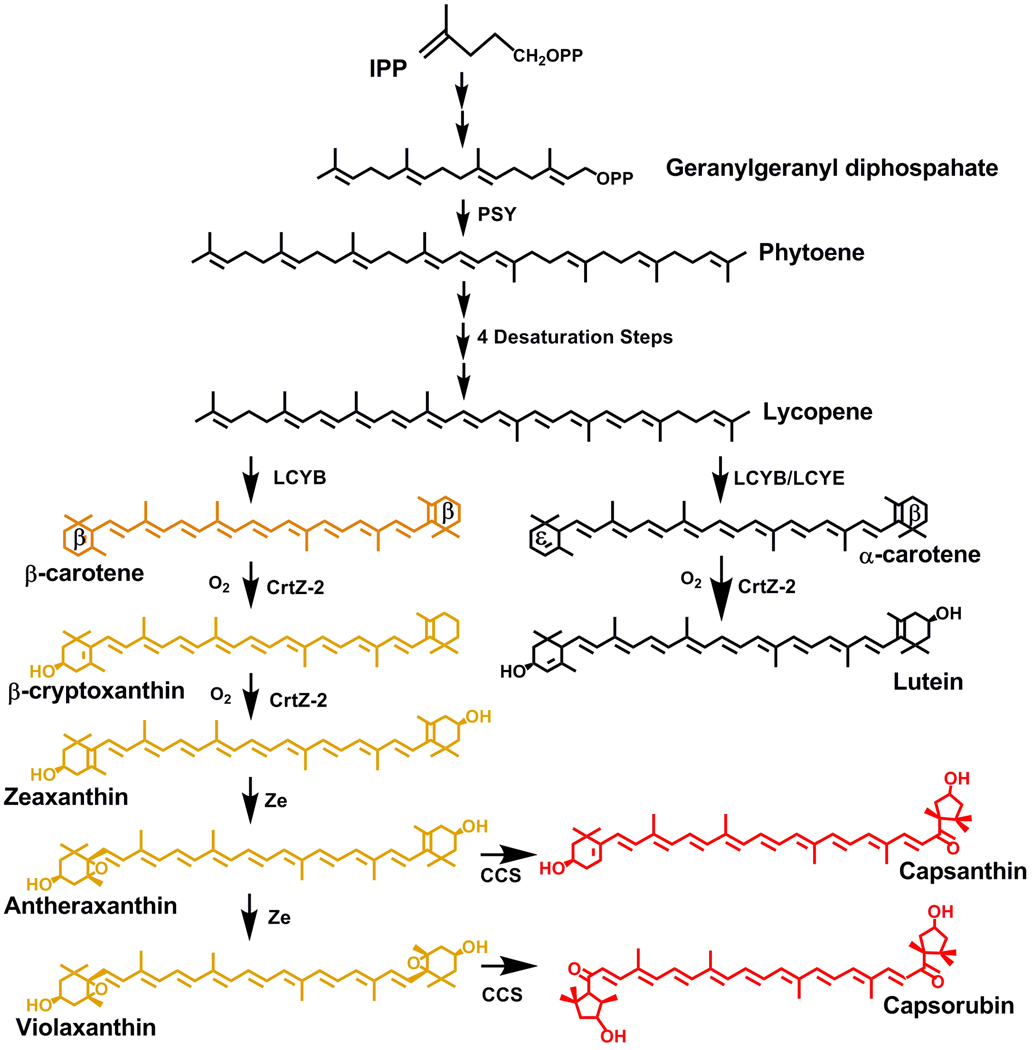

Carotenoids are responsible for a variety of colors ranging from yellow to red, as is apparent in fully mature ripe Capsicum fruits. Carotenoids are lipid soluble compounds derived from the isoprenoid pathway and share a 40-carbon isoprene backbone with a variety of ring structures at one or both ends, which in the case of pepper fruits are stored in the chromoplasts [5]. The carotenoid pathway begins with the rate-limiting step, the synthesis of phytoene by phytoene synthase [6]. Several desaturation reactions convert phytoene to the orange colored β-carotene, and then β-carotene is oxygenated to form xanthophylls like β-cryptoxanthin, zeaxanthin, and antheraxanthin (Fig. 1). Capsicum species uniquely have capsanthin-capsorubin synthase (CCS) that synthesizes two red pigments, capsanthin and capsorubin [7,8].

Fig. 1. Carotene and xanthophyll biosynthetic pathway in Capsicum.

Capsicums are one of the oldest and most popular vegetables and spices in the world [9]. In the United States, consumption of colored Capsicum fruits has increased dramatically over the last two decades [10]. Pepper fruits range in color starting at green, ivory, or yellow and ripening to variety of colors including brown, orange, red, violet, or yellow mature stages [11]. Due to the range of colors in Capsicum fruits, and the importance of carotenoid accumulation in ripe Capsicum fruits, studies have documented carotenoid levels in many varieties [5,12]. Not all orange colored organs in plants are due to accumulations in β-carotene; for example, the orange color in carrots (Daucus carota L.) is due to an accumulation of β-carotene, while the orange color in papaya (Carica papaya L.) is due to a diluted concentration of the red carotenoid lycopene [13].

Expression levels of the carotenoid biosynthetic genes are directly linked to high levels of total carotenoid accumulation in Capsicum [14,15], however regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis is not understood. The biosynthetic steps for the conversion of the C40 terpenoid, phytoene, into carotenes and xanthophylls have been determined in Capsicum [5]. In peppers, there are at least 34 unesterified carotenoids that have been extracted and separated using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). These include β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin, capsanthin, and capsorubin [5]. The heredity of mature pepper fruit color nonetheless is still not fully understood. Hurtado-Hernandez and Smith [16], reported three independent loci determining fruit color and eight phenotypes in the F2 segregation of a hybridization of a red and white pepper. This study showed that red color is dominant over white and yellow. Lefebvre et al. [17] and Huh et al. [18] characterized two loci, the phytoene synthase gene and the capsanthin-capsorubin gene. The third locus predicted by Hurtado-Hernandez has not been identified. The three-locus model offers multiple theories for the production of an orange phenotype in Capsicum fruits. U.S. Patent number 5,4440,069 [19] describes an orange dominant pepper where two orange peppers when hybridized produce orange, not red, F1 fruits; C. annuum cv. Valencia is a dominant orange pepper (S. Czaplewski, pers. comm.).

Phenotypic recurrent selection could increase abundance of a specific metabolite. It has allowed a 3-fold increase of petal color in red clover [20]. Similarly, phenotypic recurrent selection can be used to increase nutritive value of a crop if the phenotype is related to a metabolite associated with the nutritive value of the crop [21]. Therefore, the characterization of the orange phenotype is important to plant breeders wanting to increase the abundance of β-carotene in the fruit. For example, in Capsicum, if an orange fruit phenotype was associated with high β-carotene levels, selecting for a more provitamin A rich fruit could be accomplished quickly and efficiently.

In this study, we investigated the β-carotene content of red and orange-fruited Capsicum varieties to examine the relationship between fruit color and β-carotene content. The genotypes selected included a variety of pod types, as there is a wide range of carotenoid levels among the different pod types [12]. From these results we expected to determine if orange fruit color is always associated with accumulations of β-carotene. A detailed study of seven orange pepper varieties, characterizing six carotenoids and DNA sequences of four carotenoid biosynthetic genes was performed to identify metabolic and genetic differences among C. annuum orange peppers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material

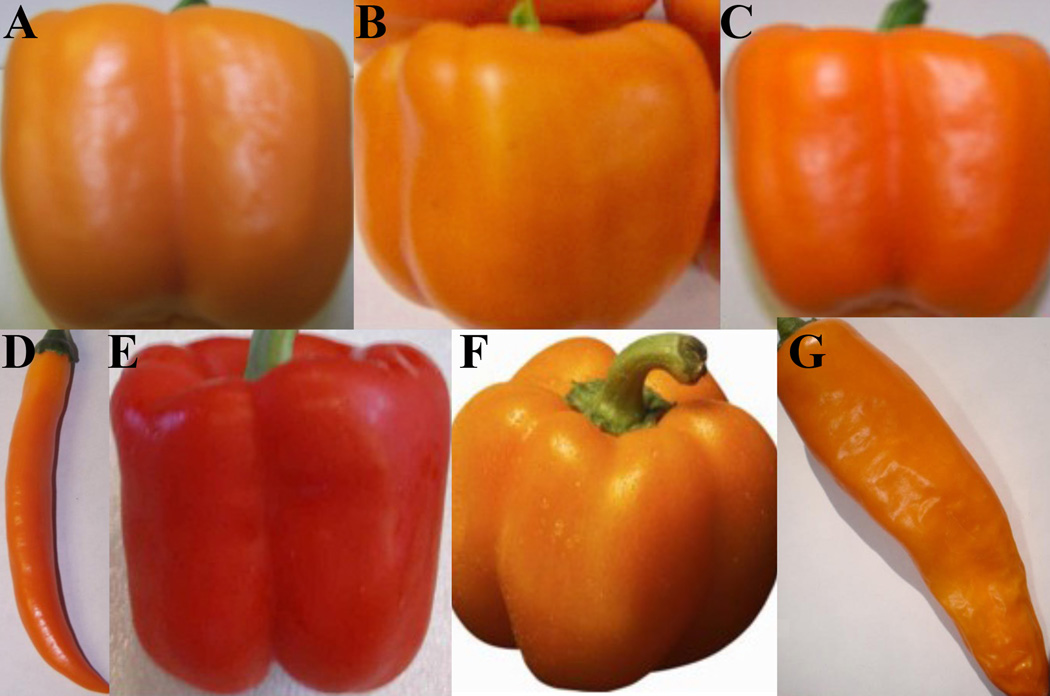

Forty different genotypes from three species (C. annuum L., C. baccatum L., and C. chinense Jacq.) were extracted for carotenoid identification and quantification. Seven orange C. annuum cultivars (Valencia, NuMex Sunset, Fogo, Orange Grande, Canary, Oriole and Dove) were used for a more detailed analysis of carotenoid composition and genetic makeup (Fig. 2). The plants were grown either at the Fabian Garcia Science Center in Las Cruces, NM or under greenhouse conditions as described earlier [22]. The fruits were harvested at the fully mature stage and within 1 h the pericarps were dissected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently lyophilized prior to carotenoid extraction. Young leaves were used for DNA extractions.

Fig. 2. Mature orange pepper lines.

From left to right, top to bottom: (A) Valencia, (B) Orange Grande, (C) Oriole, (D) Fogo, (E) Dove, (F) Canary, (G) NuMex Sunset.

2.2 Extraction and chromatography

Fruit carotenoids were extracted using a hexane extraction procedure [23] and analyzed using either high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a solvent system adapted from Wall et al., [12] or using ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC). Briefly, 1.5 g of lyophilized pericarp was extracted with hexane on ice using a polytron. The filtered extract was dried with sodium sulfate and stored in amber vials at 4°C until use. For HPLC, samples (20 µL) were analyzed on an ODS Hypersil C-18 narrow-bore column (5 µm, 100 × 2.1 mm). The eluent consisted of 39:53:8 acetonitrile:2-propanol:water (A) and 60:40 acetonitrile:2-propanol (B). The gradient profile was 0 to 20 min from 0 to 100% B (adapted from [12]). The flow rate was set at 0.3 mL/min, column temperature at 40°C. Standard solutions of β-carotene and a non-provitamin A carotenoid capsanthin (0.1 to 1.0 mg/mL) were used to make calibration curves at 454 nm. Peaks corresponding to β-carotene and capsanthin in the extracts were identified. Triplicate extractions were performed on each Capsicum genotype and the average concentration for each carotenoid was calculated following independent HPLC analysis. Total carotenoids were quantified by summing total peak area. Concentration of total carotenoids was then estimated using the β-carotene standard curve.

For UPLC, samples (2 µL) were analyzed using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC System; resolved with 10% isopropanol (v/v) (A) and 100% acetonitrile (B) and Waters Acquity C18 1.8 µm HSS particle, 2.1 × 100 mm column. The solvent profile included two linear phases (0 to 3 min at 75% B; 3 to 3.2 min from 75% B to 95% B; 3.2 to 11 min from 95% B to 100% B). The flow rate was set at 0.75 mL/min and detector wavelengths at 454, 470, and 436 nm. Calibration curves were generated with β–carotene, Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA); and capsanthin, capsorubin, zeaxanthin, antheraxanthin, and β-cryptoxanthin, CaroteNature GmbH (Lupsingen, Switzerland). Triplicate extractions were performed on each Capsicum genotype and the average concentration for each carotenoid was calculated following independent UPLC analyses.

2.3 Saponification of Fogo extract

The hexane carotenoid extract of the cultivar Fogo was dried under N2 gas flow, resuspended in ethyl acetate, and 300 µL were saponified with 300 µL methanolic KOH at 50°C for one hour. The solution was extracted with 600 µL 1:1 chloroform:water and centrifuged to resolve the phases. The bottom layer was collected. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates resolved with 5% butanol: 76% hexane: 9.5% ethyl acetate: 9.5% dichloromethane (v/v) were used to monitor the saponified and unsaponified samples. Five carotenoid standards (β-carotene, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin, capsanthin, and capsorubin) were spotted adjacent to the unsaponified and saponified extracts and used as reference. Five µL of the extracts were plated. A picture of was taken using a Seiko Epson scanner. Carotenoid migration distances were measured relative to the solvent front.

2.4 PCR, sequencing of genomic DNA, and expression of Ccs-3 Transcript

Genomic DNA was isolated from young pepper leaves. Tissue was harvested and immediately placed in liquid nitrogen. The samples were ground into a fine powder while still frozen. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Kit by Qiagen. PCR was used to amplify phytoene synthase (Psy), lycopene β-cyclase (Lcyb), β-carotene hydroxylase (CrtZ-2) and capsanthin-capsorubin synthase (Ccs). Total genomic DNA of young pepper leaves was amplified in the presence of both upstream and downstream primers for each gene. Primers were designed from mRNA sequences published on Genbank for Psy, Lcyb, and CrtZ-2 structural genes (Table 1). Amplification of Ccs was done using known primers [24]. The external primer pairs were used to clone full length genes; the internal primer pairs were used in DNA sequencing reactions to generate overlapping double stranded DNA sequences for each clone. For each gene in each cultivar, four to six clones were sequenced in order to account for both alleles in possible heterozygous cultivars. All DNA sequence files were aligned using DNASTAR software.

Table 1.

External (ext) and internal (int) primer sequences used in PCR for four carotenoid structural genes. Published external primers for Ccs [24].

| Gene (GenBank #) |

Primers (5’–3’) | |

|---|---|---|

| Psy | ext | F: ATGTCTGTTGCCTTGTTATGGGTTG |

| (X68017) | R: GGCTTCGATCTCGTCCAG | |

| int | F: GAGGGTCACCAGTGATACG | |

| R: GCCTGTGCTAATTCATCTTGAGGC | ||

| Lcyb | ext | F: GCACCTTGTTGGGAAAATATGGATACGC |

| (X86221) | R: GATCCCAGATAAGTCGAATTCATTC | |

| int | F: GCAATGATGGTATTACTATTCAGGCG | |

| R: CCCAAGTGACTTAAACGAGCCACCATTCGTTC | ||

| Crtz | ext | F: CCTTCACCGTACCGTACATGGC |

| (Y09225) | R: GCGAAGCTTGTTGTATTATATTATACTTATATA | |

| int | F: GTACATTCGCTCTCG | |

| R: CCTGATGTGCTGCAGCTACTCTC | ||

| Ccs | ext | F: CCTTTTCCATCTCCTTTACTTTCCATT |

| (X77289) | R: AAGGCTCTCTATTGCTAGATTGCCCAG | |

| int | F: GCCAAGGTTTTGAAAGTGC | |

| R: CGGAAGTGGTCCTCCC | ||

Total RNA was extracted from ripe orange Fogo pericarp using a previously described method [25]. Reverse-transcription PCR was used to screen Fogo RNA for Ccs transcripts. The primers utilized were the external primers listed in Table 1. The RT-PCR method used was that described by the manufacturer of SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen Life Technologies).

3. Results

3.1 Variability of provitamin A in Capsicum cultivars

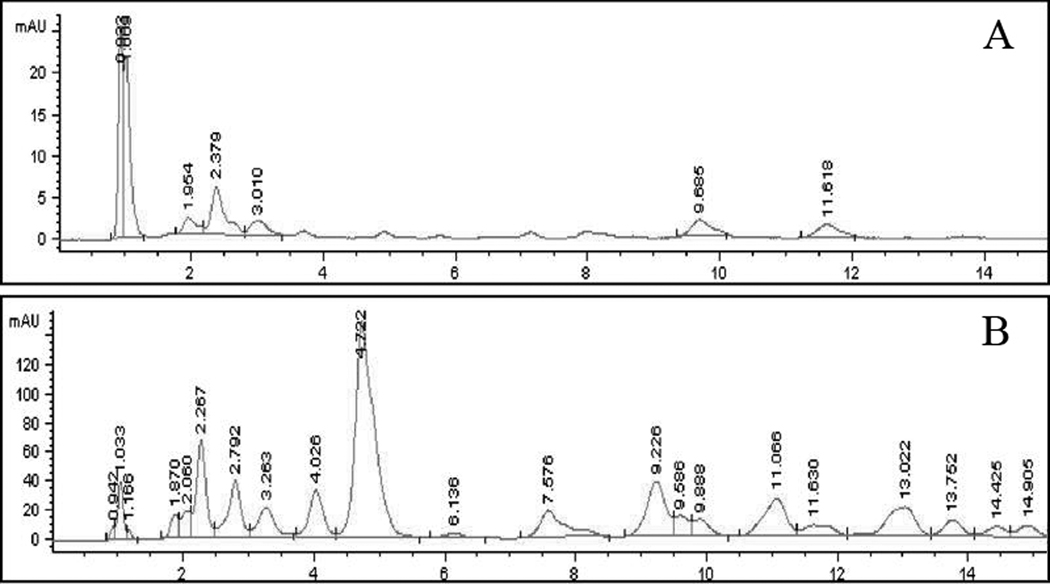

A collection of 28 cultivars that ripened to red, orange, or yellow colored fruit were screened to determine if total carotenoids and β-carotene levels differed as a function of mature fruit color. An HPLC system that was able to resolve capsanthin and β-carotene, as well as reflect total carotenoid content detected by absorbance at 454 nm was utilized (Fig. 3). The chromatograms for the carotenoids in Capsicum fruit extracts are complex; two contrasting examples are presented, C. annuum, Blushing Beauty (Fig. 3A), an orange colored bell pepper, and C. annuum, Costeño Amarillo (Fig. 3B), a pungent orange colored fruit with a pod shape similar to cayenne peppers. Both samples had detectable levels of capsanthin, peaks at ~1.0 min, however, a peak for β-carotene (~5.0 min) was detected only in the Costeño Amarillo sample (Fig. 3B). Chromatograms for triplicate extracts of the 28 pepper varieties were analyzed and the mean levels of results of β-carotene, capsanthin, and total carotenoids in mg/g dry weight (DW) are listed in Table 2. The percent of total peak area of the chromatogram represented by β-carotene and capsanthin is also reported.

Fig. 3. HPLC chromatograms of carotenoid profiles in orange peppers.

Pericarp extracts were characterized using HPLC system. Samples were separated on an ODS Hypersil C-18 narrow-bore column (5 µm, 100 × 2.1 mm) using Hewlett-Packard 1090 series with a photodiode array detector (454 nm). Column was eluted at 0.3 mL/min, 40°C with 0 to 100% b; (a) 39:53:8 acetonitrile: 2-propanol:water; (b) 60:40 acetonitrile: 2-propanol. Retention times for standards were, capsanthin (~1.0 min) and β-carotene (~5.0 min). (A) Blushing Beauty. (B) Costeño Amarillo.

Table 2.

Carotenoid concentrations in pericarp of mature fully ripe Capsicum fruits. Carotenoid levels were determined using HPLC on hexane extracts of lyophilized pericarp. Cultivars grouped by fruit phenotypic color and rank-ordered by total carotenoid concentration; all concentrations are reported as mean of triplicate extractions (± SE) in mg/g DW.

|

Capsicum spp. |

Cultivar | Color | β- carotene |

Capsanthin | Assigned Peaks % of Total |

Total Carotenoids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| annuum | Nambe | Red | 0.58 ± 0.22 | 3.03 ± 0.64 | 33.6 % | 10.76 ± 2.54 |

| NuMex Nematador | Red | 0.56 ± 0.40 | 4.01 ± 2.86 | 50.4 % | 9.07 ± 2 | |

| Giant Thai | Red | 1.32 ± 0.26 | 1.15 ± 0.05 | 37.7 % | 6.55 ± 0.34 | |

| Pimiento | Red | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 2.98 ± 0.77 | 55.0 % | 5.68 ± 0.46 | |

| Andy | Red | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 21.0 % | 5.56 ± 0.52 | |

| NuMex Garnet | Red | 1.16 ± 0.05 | 0.66 ± 0.45 | 34.0 % | 5.34 ±1.38 | |

| Indian PC-1 | Red | 1.36 ± 0.11 | 0.44 ± 0.12 | 47.9 % | 3.76 ± 0.83 | |

| Sandia | Red | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 28.4 % | 3.35 ± 0.56 | |

| Blackbird | Red | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.76 ± 0.27 | 85.0 % | 2.11 ± 0.42 | |

| Big Red Cayenne | Red | 0.41 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0 | 40.0 % | 1.60 ± 0.15 | |

| Hungarian Apple | Red | 0.14 ± 0 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 29.6 % | 1.52 ± 0.18 | |

| Sweet Banana | Red | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 59.4 % | 0.69 ± 0.39 | |

| NuMex Centennial | Red | 0.12 ± 0.10 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 76.2 % | 0.21 ± 0.08 | |

| Gourmet Rainbow | Orange | 0.50 ± 0 | 0.95 ± 0 | 39.5 % | 3.67 ± 0 | |

| Costeno Amarillo | Orange | 1.24 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 43.8 % | 3.52 ± 0.50 | |

| Orange Thai | Orange | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | 46.5 % | 2.45 ± 0.43 | |

| Oriole | Orange | 0.28 ± 0.10 | 0.60 ± 0.12 | 61.1 % | 1.44 ± 0.42 | |

| Early Sunsation | Orange | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 54.3 % | 0.46 ± 0.23 | |

| Blushing Beauty | Orange | 0 ± 0 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 45.2 % | 0.31 ± 0.01 | |

| Alba | Orange | 0.01 ± 0 | 0.05 ± 0 | 40.0 % | 0.15 ± 0.01 | |

| Mandarin | Orange | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 92.3 % | 0.13 ± 0.01 | |

| NuMex Thanksgiving | Orange | 0.01 ± 0 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 80.0 % | 0.05 ± 0.017 | |

| NuMex Sunglo | Yellow | 0 ± 0 | 0.12 ± 0 | 40.0 % | 0.30 ± 0 | |

| Yellow Cheese Pimiento |

Yellow | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.10 ± 0 | 45.2 % | 0.31 ± 0 | |

| baccatum | Bolivian Yellow | Orange | 0.20 ± 0.18 | 0.92 ± 0.86 | 44.8 % | 2.50 ± 1.20 |

| chinense | Aji Dulce | Red | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.22 | 59.1 % | 1.10 ± 0.24 |

| Jamaican Hot Chocolate |

Brown | 0.20 ± 0.18 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 33.7 % | 0.89 ± 0.43 | |

| Jamaican Yellow | Yellow | 0.28 ± 0.13 | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 33.1 % | 1.48 ± 0.70 | |

As expected there is considerable variability for levels of total carotenoids, β-carotene and capsanthin in fruit pericarp from the 28 different lines. For total carotenoid amounts, the fruits ranged from 0.05 mg/g DW in NuMex Thanksgiving an orange colored fruit to 10.76 mg/g DW in Nambe a red colored fruit. Within the red colored fruit, β-carotene levels ranged from 0.09 mg/g DW in Blackbird to 1.36 mg/g DW in Indian PC-1 and capsanthin levels ranged from 0.04 mg/g DW in NuMex Centennial to 4.01 mg/g DW in NuMex Nematador. There were several lines within the red colored fruit, where the levels of β-carotene were as high or higher than the capsanthin levels: Giant Thai, NuMex Garnet, Indian PC-1, Big Red Cayenne, Sweet Banana, and NuMex Centennial.

In orange fruits, total carotenoid amounts varied from 0.05 to 3.67 mg/g DW in NuMex Thanksgiving and Gourmet Rainbow, respectively. β-carotene levels ranged from 0 mg/g DW in Blushing Beauty to 1.24 mg/g DW in Costeño Amarillo and capsanthin levels ranged from 0.03 mg/g DW in NuMex Thanksgiving to 0.95 mg/g DW in Gourmet Rainbow. There were several lines within the orange colored fruit, where the levels of capsanthin were as high or higher than the β-carotene levels: Gourmet Rainbow, Oriole, Early Sunsation, Blushing Beauty, Alba, Mandarin, and NuMex Thanksgiving. In fact β-carotene was the predominant carotenoid in only two lines with orange colored fruit, Costeño Amarillo and Orange Thai. The most striking result was that some phenotypic orange fruit had no β-carotene, e.g., Blushing Beauty or extremely low levels, e.g., Alba and NuMex Thanksgiving. However, these orange colored fruits did contain capsanthin.

Three phenotypic yellow-fruited cultivars were extracted and the carotenoid level ranged from 0.30 to 1.48 mg/g DW for NuMex Sunglo and Jamaican Yellow, respectively. Jamaican Yellow had higher amounts of β-carotene than capsanthin, while NuMex Sunglo had no β-carotene and 0.12 mg/g DW capsanthin. In some of these cases, total carotenoid concentration was as high in yellow fruits as in red or orange. Over all 28 lines regardless of apparent color, 63% of the fruit analyzed contained higher amounts of capsanthin and β-carotene, 30% had more β-carotene than capsanthin and 7% had similar amounts of both.

3.2 Quantification of carotene and xanthophylls in orange colored peppers

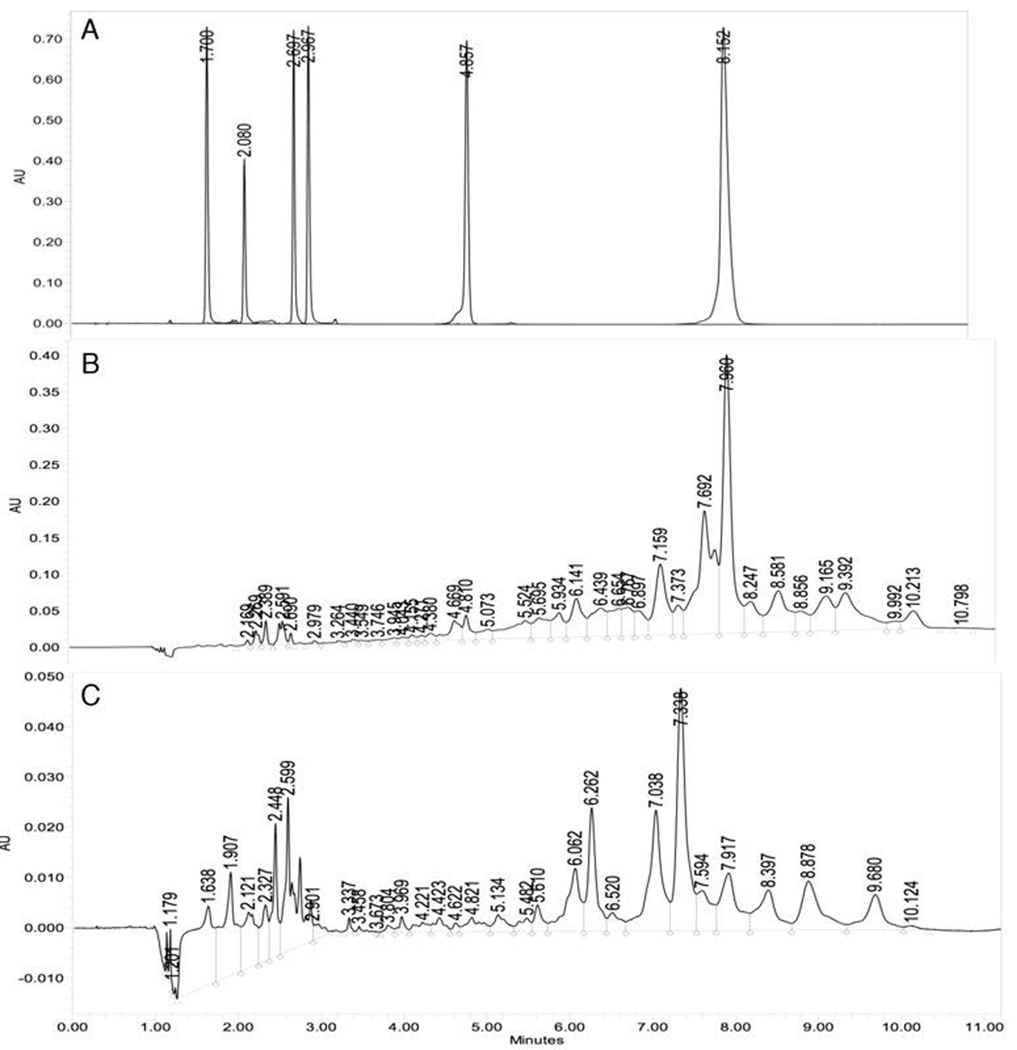

In order to identify additional carotenoids within the pericarp extract, a UPLC system was developed that efficiently separated six carotenoid standards with unique elution times (Fig. 4A). The xanthophylls: capsanthin, capsorubin, zeaxanthin, and antheraxanthin, eluted from the column before β–carotene, with β-cryptoxanthin in between at 4.95 min. Linear response range of the calibration curves for these standards was from 0 to 250 µg/mL, with regression coefficients greater than 0.90.

Fig. 4. Resolution of Capsicum pericarp carotenoids by UPLC.

Carotenoids detected by absorption at 454 nm, following separation on a Waters Acquity C18 column as described in methods. (A) Standards (each at 100 ppm): capsorubin (1.7 min), capsanthin (2.08 min), antherxanthin (2.69 min), zeaxanthin (2.97 min), β-cryptoxanthin (4.86 min), and β-carotene (8.15 min). (B) Valencia pericarp extract. (C) NuMex Sunset pericarp extract.

Two representative chromatograms of pepper extracts are presented in Fig. 4. The middle panel (Fig. 4B) displays the carotenoid composition in an extract from Valencia, the cultivar patented for the dominant orange fruit color phenotype. The lower panel (Fig. 4C) displays the carotenoid composition in an extract from NuMex Sunset, also an orange colored fruit. Comparing peak areas between Valencia, the dominant orange pepper, and NuMex Sunset convey differences in total carotenoid content (Table 3): Valencia containing a larger total peak area. The peak corresponding to β-carotene was the largest in Valencia and was a minor one in NuMex Sunset. The prevailing peaks in NuMex Sunset were observed between 6 and 8 minutes, which did not co-elute with any standards depicted in the top panel (Fig. 4A).

Table 3.

Quantification of total carotenoids in mature orange Capsicum fruits. Total carotenoids calculated as if β–carotene.

| Cultivar | Assigned Peaks µg/g DW |

Assigned Peaks % of Total |

Total Carotenoids µg/g DW (Abs 454 nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valencia | 82 ± 5.7 | 37.1 | 221.2 ± 17.9 |

| NuMex Sunset | 31 ± 1.3 | 82.2 | 37.7 ± 2.2 |

| Fogo | 74.1 ± 5.9 | 34.6 | 214.0 ± 35.2 |

| Orange Grande | 104.5 ± 2.1 | 33.0 | 316.9 ± 17.4 |

| Canary | 37.1 ± 1.7 | 51.9 | 71.4 ± 8.4 |

| Oriole | 102.1 ± 4 | 33.2 | 307.3 ± 18.6 |

| Dove | 38.1 ± 4.1 | 44.4 | 85.8 ± 1 |

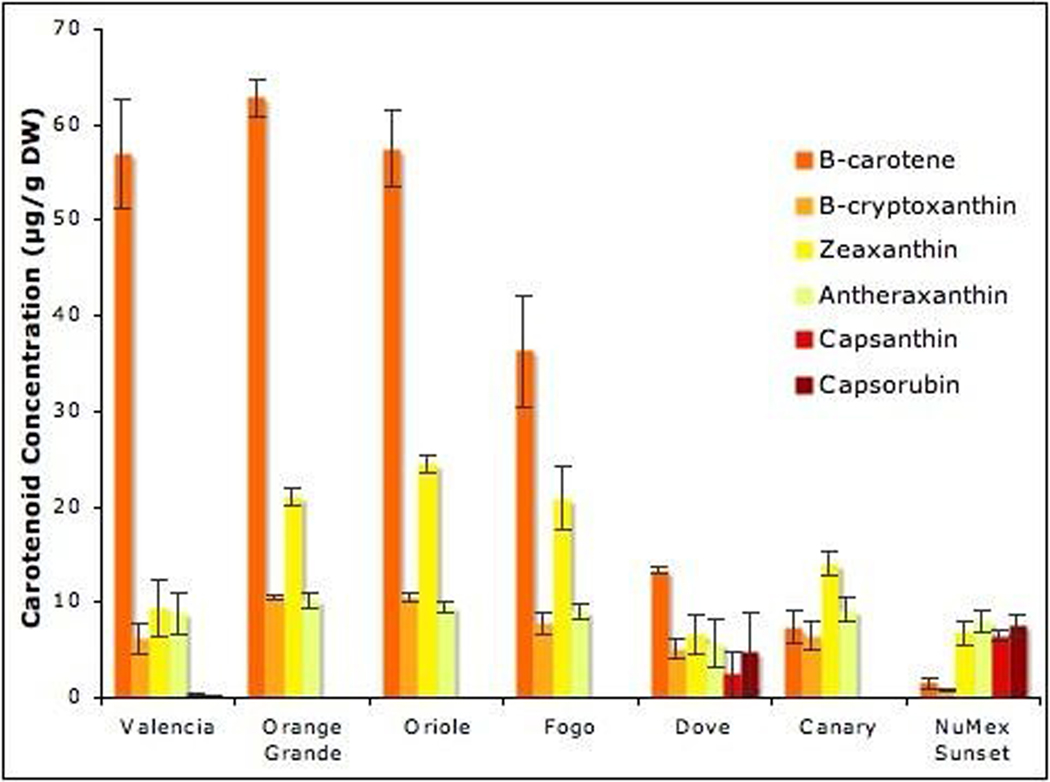

The most abundant carotenoid in most orange peppers was β–carotene, with NuMex Sunset and Canary being the exception (Fig. 5). The orange color can be explained by accumulation of the orange carotenoids, as was the case in Valencia, Fogo, Orange Grande, Canary and Oriole. An orange color is also apparent if the pepper has a mixture of red and yellow carotenoids like in NuMex Sunset. Valencia, the dominant orange pepper, did show some production of capsanthin and capsorubin, however they were in very small quantities.

Fig. 5. Carotenoids in orange Capsicum annuum cultivars.

Abundance of six carotenoids in hexane extracts of mature C. annuum fruit. Extracts were prepared and the concentration of carotenoids in µg/g DW determined by UPLC; values of the average ± SE from triplicate extractions are shown.

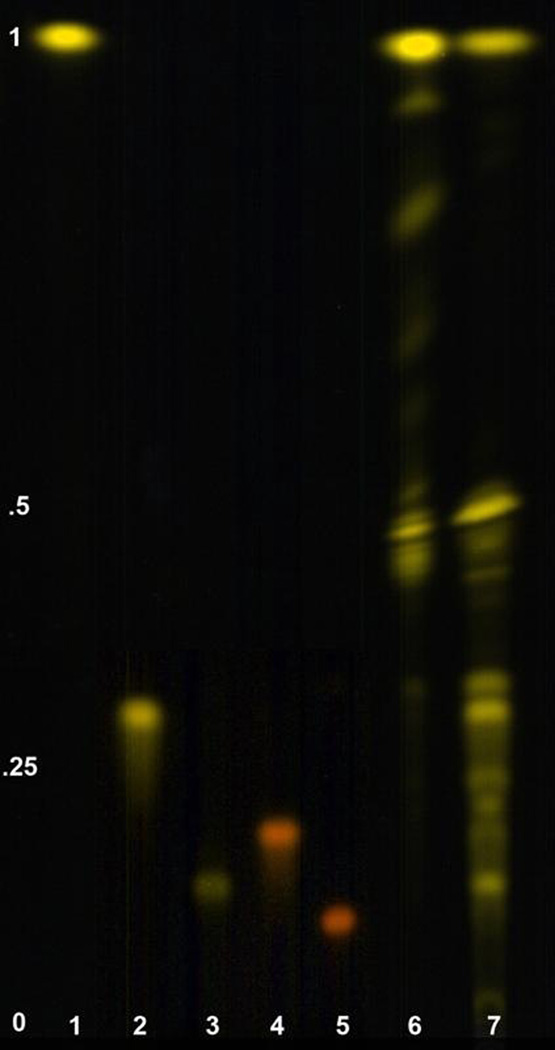

3.3 Saponification of esterified xanthophylls in Fogo extract

The majority of xanthophylls (50 – 80%) accumulated in ripe pepper fruits are totally or partially esterified [26]. Many of the orange cultivars showed very little or no amounts of capsanthin or capsorubin. Xanthophylls like the yellow and red pigments are esterified in the plant and therefore when analyzed in a chromatographic system, will shift retention times compared to the nonesterified standards. This would then affect the quantities reported in Fig. 5. Table 3 clearly shows that there are still many carotenoids present in the samples that were not identified. To confirm the absence of capsanthin and capsorubin in Fogo, extracts were saponified and then characterized. UPLC analysis of Fogo resulted in no red pigments and after separation using TLC, again no red pigments were found (Fig. 6; Lane 6). The extract before saponification in lane 6 did show the presence of yellow pigments with an Rf larger than 0.5, while only 3 spots were observed with an Rf lower than 0.5. After saponification, the spots with Rf values between 0.5 and 1 in lane 6 shifted to slower Rf values between 0 and 0.4 in lane (Fig. 6), suggesting that these were de-esterified after the saponification reaction.

Fig. 6. Thin layer chromatography of unsaponified and saponified Fogo extracts.

lane 1- β-carotene; lane 2 – zeaxanthin; lane 3 – violaxanthin; lane 4 – capsanthin; lane 5 capsorubin; lane 6 – unsaponified Fogo extract; lane 7 – saponified Fogo extract.

3.4 Novel carotenoid biosynthetic gene sequences

3.4.1 Phytoene Synthase

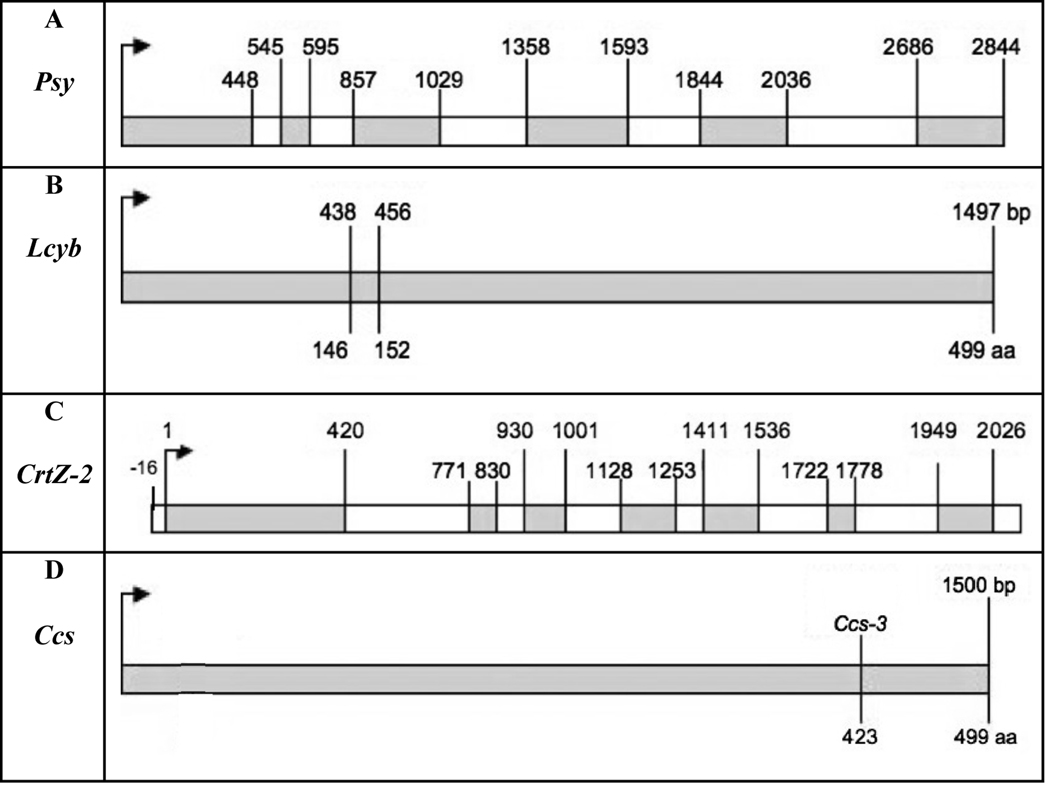

The phytoene synthase cDNA sequence is available in GenBank (X68017). There are two phytoene synthase genes in Capsicum, however only one segregates with color and Thorup et al. [8] mapped it to chromosome 4. The Psy primers used amplified a 2844 bp PCR fragment and a BLAST result confirmed it was phytoene synthase. The product included five introns. The predicted gene is 420 amino acids long. Fig. 7A indicates the positions for the exons and introns. The predicted mRNA for all cultivars was the same as the sequence found in GenBank. The seven PSY gene sequences from these varieties have been deposited in GenBank (GU085273 to GU085279).

Fig. 7. Gene diagrams illustrating exons and introns found in orange Capsicum cultivars.

The start codon is designated by an arrow. (A) Psy, 2849 bp long, with five introns indicated by white boxes and exons indicated by gray boxes. (B) Lcyb, 1497 bp long, included two amino acid changes at positions 146 and 152 resulting from nucleotide changes at base pair positions 438 and 456 are indicated. (C) CrtZ-2, 2150 long contains six introns and seven exons. (D) Ccs, 1494 bp long. Ccs-3 stop at amino acid 423.

3.4.2 Lycopene β-Cyclase

The Lcyb primers were able to amplify a 1495 bp product. Thorup et al. [8] mapped Lcyb to chromosome 10. No introns were found in this gene. There was a consensus sequence present in all orange cultivars analyzed. An alignment of the orange consensus sequence with the sequence published in GenBank (X86221) revealed a difference in two amino acids (Fig. 7B). The predicted protein is 499 amino acids long. The amino acid sequence differed in two locations: at 146 and 152 (Fig. 7B). At amino acid 146, the change was from alanine, a hydrophobic amino acid, to threonine, a hydrophilic amino acid. At position 152, the change was from lysine, a basic amino acid, to asparagine, a hydrophilic amino acid. The amino acid changes were due to nucleotide changes in nucleotide position 436 and 456 (Fig. 7B). This variant of Lcyb was present in all orange cultivars. The seven Lcyb gene sequences from these varieties have been deposited in GenBank (GU085266 to GU085272).

3.4.3 β-Carotene Hydroxylase

There are two β-carotene hydroxylase genes in pepper. The one expressed in fruit, CrtZ-2, is mapped to chromosome 3 [8]. The primers used for β-carotene hydroxylase amplified a 2150 bp PCR fragment. The coding region was 2026 bp long (316 amino acids long) and contained 6 introns (Fig. 7C). The predicted coding region was the same in all seven orange lines and was identical to the cDNA sequence published in GenBank (Y09225). The seven CrtZ-2 gene sequences from these varieties have been deposited in GenBank (GU122940 to GU122946).

3.4.4 Capsanthin-Capsorubin Synthase

GenBank contained the Ccs mRNA sequence 499 amino acids long amplified from Yolo Wonder, a red fruited pepper (X77289). Thorup et al. [8] only found one copy of Ccs and mapped it to chromosome 6. The primers developed for Ccs amplified a 1494 bp product with no introns (Fig. 7D). In this study, all orange cultivars except Fogo had the same Ccs sequence named CcsWT identical to Ccs from Yolo Wonder.

Fogo, however, contained a new variant (Ccs-3) with an early translation termination stop of the Ccs gene (Fig. 7D). This variant contained a deletion of cytosine at nucleotide position 1283 (Fig. 7D), also causing a frameshift in coding sequence and resulting in a 423 amino acid sequence. Further analysis in Fogo using reverse transcription confirmed that the Ccs-3 transcript is made; the DNA sequence of the RT-PCR product also confirmed this deletion variant in Ccs-3. Transcripts for Ccs-3 were also detected in Fogo RNA samples using northern blots (data not shown). The wildtype Ccs sequences found in six varieties were deposited in GenBank (GU122934 to GU122939), along with the Ccs-3 gene sequence from Fogo (GU122933).

4. Discussion

Peppers make and accumulate carotenes and xanthophylls ranging in color from yellow to red. However the regulation of the biosynthetic enzymes or genetic differences in those enzymes has not been studied sufficiently well to explain these fruit phenotypes. In 1985, Hurtado-Hernandez and Smith [16] proposed a three-locus model (c, y1, y2) to explain fruit color inheritance in Capsicum. According to this model, red color is dominant in a cross between red and white fruited pepper. Further, they describe eight different loci combinations and the respective fruit colors. This model offers more than one way to produce an orange color in the progeny; [yc1+c2+, y+c1+c2, y+c1c2, yc1+c2]. In this study, for the first time, the carotenoid composition of orange fruited Capsicum lines was defined along with the allelic variability of the biosynthetic enzymes. These results support the three-locus model for Capsicum fruit color inheritance.

4.1 β-carotene accumulates at different concentrations

Carotenoids not only include provitamin A compounds like β-carotene, but members of this chemical class can also be antioxidants. Analysis of 29 Capsicum cultivars using the HPLC method, quantified provitamin A amounts (Table 2). Within the orange fruited group of peppers, large variation in the accumulation of both β-carotene and capsanthin was observed. In an earlier survey of carotenoid levels in Capsicum lines, Wall et al. [12] screened primarily red colored fruit, and also observed wide ranges in carotenoid and β-carotene levels across varieties. They did not saponify their samples, and they did not report capsanthin levels. In some cultivars, β-carotene and capsanthin accounted for less than half of the carotenoids present, indicating that other carotenoids are present.

Orange colored fruit can have high amounts of β-carotene or very low amounts, indicating that phenotypic recurrent selection is not an effective breeding method to increase the β-carotene level in Capsicum. These results illustrate that orange colored Capsicum fruits can be derived from at least two different chemical profiles. According to a study by Lancaster and Lister [27], they concluded that a color with the same hue and chroma values could be achieved with a combination of different pigments. In the case of orange peppers, one genotype of orange fruit has high amounts of β-carotene, which would be the best source for breeding peppers to increase the pro-vitamin A level, and thus could contribute to the reduction of vitamin A deficiency. The other orange genotype consists of a mixture of red and yellow carotenoids (Fig. 5). Because β-carotene is the precursor to vitamin A, an essential nutrient to humans, the vitamin A quantity offered by orange peppers in our diet is not consistent from one orange cultivar to another. When selectively breeding for high pro-vitamin A levels, phenotypic recurrent selection based on fruit color is not sufficient, carotenoid chemical composition should also be conducted. Considering that the U.S. population is increasing their pepper consumption, it is important to breeders working on improving nutritional value in peppers. Phenotypic recurrent selection is also used to increase a desired trait in other fruits and vegetables and this study shows that in some situations, it is not an ideal breeding method. A visible trait like color could be the result of different pigment combinations.

4.2 Novel UPLC method developed for quantification of carotenes and xanthophylls

HPLC, however, had limitations in efficiently separating carotenoid standards. In order to accurately characterize the composition of carotenoids in peppers, a novel UPLC chromatography method was developed sufficient to separate six carotenoid standards. The chemical diversity of carotenoids in orange peppers (20 to 40 distinct peaks) required better resolved carotenoid chromatograms for pepper extracts giving breeders more information about a cultivar. This UPLC method can be used when resolving carotenoids in any other crop; the method will allow much more accurate conclusions as to the role of specific carotenoids in a phenotype.

The novel UPLC method allowed for the quantification of orange, red, and yellow carotenoids in seven orange pepper cultivars. The orange phenotype composed of a mixture of reds and yellows was evident in NuMex Sunset. It appears orange but in reality contained a combination of yellow and red pigments, which make up approximately 80% of the total carotenoids present. The cultivar Canary also exhibited small amounts of β-carotene and overall carotenoids giving it an orange-yellow appearance, while no red pigments were detected (Fig. 5). Valencia and the other orange cultivars did accumulate larger amounts of the β-carotene as expected.

4.3 Saponification uncovered formerly esterified xanthophylls in Fogo extract

Many of the orange cultivars showed very little or no amounts of capsanthin or capsorubin. To check for esterified pigments, the Fogo extract was saponified and resolved on TLC plates (Fig. 6) illustrating the extract before and after saponification. There was a shift in xanthophylls to slower Rf values indicating removal of ester groups. The dilemma with saponification is the destruction of analytes during the process. Fig. 6 also demonstrates the reduction in recovery of carotenoids following the saponification treatment. This was most pronounced when comparing the β-carotene bands, indicated by arrows, in lanes 6 and 7. Beta-carotene cannot be acylated so the reduction in abundance of this carotenoid in the saponified sample is not due to a change in Rf. Saponification, although somewhat destructive, could potentially reveal more formerly esterified xanthophylls.

This study quantified β-carotene, capsanthin, and total carotenoid amounts in peppers grown in the field (Table 2) and peppers grown in a controlled greenhouse environment (Table 3). Because these compounds help protect cell membranes from photooxidative damage, the content of phytochemicals in the fruit wall is influenced by factors such as the environment. The peppers grown in the field had higher amounts of carotenoids compared to those grown in a greenhouse and this could be due to an increased amount of light stress in the field versus the greenhouse.

4.4 Allelic characterization of carotenoid biosynthetic genes in orange peppers

Among the seven orange peppers, two orange phenotypes can be explained genetically. Because color is determined by three loci [16], allelic differences in the biosynthetic genes could account for malfunctioning enzymes, which would determine whether a specific carotenoid could be synthesized. Characterizing alleles associated with different fruit colors is necessary to identify sequence polymorphisms in the carotenoid biosynthetic genes. This will enable Capsicum breeders to select for fruits with increased β-carotene levels, and could help alleviate vitamin A deficiency in developing countries.

Although the cDNA sequences for these genes are available in GenBank, they are only available for one genotype; the red bell pepper, Yolo Wonder. In order to identify alleles for specific carotenoid biosynthetic genes, four crucial biosynthetic structural genes were analyzed in a number of orange peppers. Phytoene synthase (PSY) is the enzyme that is responsible for the production of phytoene, the 40-carbon backbone to all carotenoids. Psy has been associated with the locus c2, thought to be part of the three-locus model in pepper fruit color inheritance. Only one copy of Psy was found in all the orange types and this was identical to the cDNA cloned from red peppers. This would suggest that all peppers studied have a wildtype PSY enzyme and is functional due to production of carotenoids in all lines.

Lycopene β-cyclase is the enzyme that forms two β-rings on β-carotene. The Lcyb gene sequenced from these orange peppers, differs from the published cDNA sequence in red peppers. The role of the enzyme however is still functional because β-carotene is made and accumulated in all orange peppers studied, but could this new variant be a less efficient enzyme that provides less β-carotene, therefore affecting the synthesis of downstream products like capsanthin and capsorubin? In another closely related Solanaceae family member, tomato, two mutants map to this region. One mutation is lutescent-2 (l2) whose phenotype results in a delayed onset of red pigment in the fruit and photobleaching in the leaves [28]. The other mutation is Xa, which symptoms include dwarfed plants, yellow leaves and fruit color appearance similar to l2 [29]. A disturbance in gene function like the ones reported in tomato will affect the carotenoid accumulation, specifically the orange and yellow pigments. The novel amino acid changes discovered in orange peppers are not obstructing the production or accumulation of orange pigments in the studied peppers.

Beta-carotene hydroxylase hydroxylates the β-rings on β-carotene and initiates the production of xanthophylls, synthesizing yellow xanthophylls first. Mutations in tomato and potato map to the same chromosomal region that CrtZ-2 does in pepper [8]. The tomato mutant is a yellow-flesh mutant [30]. In potatoes, mutations of this locus (Y locus) cause tubers to accumulate zeaxanthin and turn from white to yellow [31]. The orange peppers used in this study produce yellow pigments (Fig. 5), and demonstrated the presence of a functional enzyme. According to the gene sequence, the coding region of CrtZ-2 was identical to the cDNA sequence published for red pepper.

The Ccs gene sequenced from the orange peppers however, revealed one novel variant of this gene. Previous reports associated Ccs with the y locus in the three-locus model of pepper color inheritance. Two separate studies indicate that a non-red pepper did not contain a functional Ccs gene, while others report the Ccs gene has a deletion in the 5’ coding region [17, 24,32]. In 2007 however, Ha et al. [14] showed that the coding and promoter regions are present in orange peppers, but not in white peppers. The study reports changes in the Ccs promoter regions of this gene from red, orange and yellow peppers, and suggests that these changes might be cultivar specific. They also report base pair insertions creating frameshifts at codon positions 200 and 477 causing early translation termination stops. A novel truncated variant, Ccs-3, found in orange Capsicum annuum used in this study showed a base pair deletion thus causing a frameshift and an early translation termination stop. From the current and previous studies, Ccs is present in orange peppers but a novel allele has been recovered.

There were three orange peppers in this study with an accumulation of red pigments and three without, but all six had at least one copy of the CcsWT allele. The two orange phenotypes analyzed contain the same coding sequence for four important carotenoid biosynthetic genes. This suggests that these coding regions are not the basis for orange color. In those cases, the orange phenotype maybe due to gene expression regulation for the genes sequenced. Thus, it would be beneficial to sequence the promoter as well to look for polymorphisms in the promoter regions. In addition to gene expression, the differences in abundance of each pigment would also affect the hue and chroma of the fruit pericarp [27].

4.5 Potential functions for novel Ccs-3 allele in orange peppers

Fogo did not accumulate any capsanthin or capsorubin and was homozygous for the Ccs-3 allele. Fogo exhibited an increase in β-carotene. Exhibiting an increase in β-carotene content has also been reported in tomato, and has been characterized as the B locus [33]. The B locus and Ccs map to the same location on chromosome 6 [8]. Ronen et al. [33] reported that the B gene encodes a novel lycopene β-cyclase, while CCS has also been reported to have lycopene β-cyclase activity. Because Fogo was found to express Ccs-3 mRNA in the northern hybridization and RT-PCR studies, could the CCS activity be altered and be aiding the synthesis of more β-carotene? Capsicum CCS and tomato NXS (neoxanthin synthase) share similarities. The nucleotide sequences showed an 85.5 % similarity, and both enzymes require the same precursor, violaxanthin, to make capsorubin by CCS and neoxanthin by NXS [34]. Capsicum accumulates neoxanthin in the green unripe stage; however, no Nxs has been cloned in it. Due to the similarities in function and sequence could variations in Ccs also affect neoxanthin production?

Considering that one novel Lcyb variant and one novel Ccs variant were found, expression studies of the discussed variants and those found in previous studies must be done within each color type and species. Sequencing the structural genes in different orange peppers is only half the question. Regulation of these genes and expression of their proteins is the missing part to understanding carotenoid biosynthesis in peppers. Studies on these gene orthologues and mutants in tomato and potato offer promising insights to better understanding the biosynthesis of carotenoids, like β-carotene.

Based on these results, Ccs-3 could provide candidate molecular markers for selection of orange pepper lines with high β-carotene and therefore high pro-vitamin A levels. These results mark significant progress in understanding carotenogenesis in peppers. Increasing β-carotene content in peppers and biofortification of other crops could help fight vitamin A deficiency. Not only have we shown that some orange peppers are high in β-carotene, but also that they have many other carotenoids, which have antioxidant properties. Zeaxanthin, for example, offers protection against macular degradation, the leading cause of age-related blindness [35].

Capsicum is the only genus known to express Ccs and synthesize capsanthin and capsorubin, red pigments with high-economic value. These carotenoids are used in industry as natural pigments to color cosmetics and food products. Research programs to improve nutritional value through metabolic engineering of the carotenoid pathway are underway in plants like rice [36] or tomato [37]. Unusual or difficult to predict phenotypes have been observed in transgenic plants engineered for secondary metabolism; making better understanding of these pathways essential [38]. The description of novel alleles and the molecular explanation of fruit color provided in this report expand the toolkit for engineering the production of carotenoid based plant pigments. Importantly, pepper breeders now have a better understanding of carotenoid synthesis and new revelations on what makes a pepper orange.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NM Agricultural Experiment Station, and grants from USDA CSREES 2008-34604-19434 and NIH R25 GM61222.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature

- 1.World Health Organization. Micronutrient deficiencies: Vitamin A deficiency. 2009 http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/vad/

- 2.Taylor M, Ramsay G. Carotenoid biosynthesis in plant storage organs: recent advances and prospects for improving plant food quality. Physiol Plant. 2005;124:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paiva SAR, Russell RM. β-carotene and other carotenoids as antioxidants. J. Amer. College Nutr. 1999;18:426–433. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Lintig J, Vogt K. Vitamin A formation in animals: molecular identification and functional characterization of carotenoid cleaving enzymes. J. Nutr. 2004;134:251S–256S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.1.251S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deli J, Molnar P, Matus Z, Toth G. Carotenoid composition in the fruits of red paprika (Capsicum annuum var. lycopersiciforme rubrum) during ripening; biosynthesis of carotenoids in red parika. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:1517–1523. doi: 10.1021/jf000958d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirschberg J. Carotenoid biosynthesis in flowering plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2001;4:210–218. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies BH, Matthews S, Kirk JTOR. The nature and biosynthesis of the carotenoids of different colour varieties of Capsicum annuum. Phytochem. 1970;9:797–805. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorup TA, Tanyolac B, Livingstone KD, Popovsky S, Paran I, Jahn M. 2000. Candidate gene analysis of organ pigmentation loci in the Solanaceae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:11192–11197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosland PW. Chiles: a Diverse Crop. HortTechn. 1992;2:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.USDA. Vegetables and Melons Outlook. 2008 http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/vgs/2008/08Aug/VGS328.pdf.

- 11.Lightbourn GJ, Griesbach RJ, Novotny JA, Clevidence BA, Rao DD, Stommel JR. Effects of anthocyanin and carotenoid combinations on foliage and immature fruit color of Capsicum annuum L. J. Hered. 2008;99:105–111. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esm108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wall MM, Waddell CA, Bosland PW. Variation in β-carotene and total carotenoid content in fruits of Capsicum. HortSci. 2001;36:746–749. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khachik F, Carvalho L, Bernstein PS, Muir GJ, Zhao D, Katz NB. Chemistry, distribution, and metabolism of tomato carotenoids and their impact on human health. Exp. Biol. Med. 2002;227:845–851. doi: 10.1177/153537020222701002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha SH, Kim JB, Park JS, Lee SW, Cho KJ. A comparison of the carotenoid accumulation in Capsicum varieties that show different ripening colours: deletion of the capsanthin-capsorubin synthase gene is not a prerequisite for the formation of a yellow pepper. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:3135–3144. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romer S, Hugueney P, Bouvier F, Camara B, Kuntz M. Expression of the genes encoding the early carotenoid biosynthetic enxymes in Capsicum annuum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1993;196:1414–1421. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurtado-Hernandez H, Smith PG. Inheritance of mature fruit color in Capsicum annuum L. J. Hered. 1985;76:211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefebvre V, Kuntz M, Camara B, Palloix A. The capsanthin-capsorubin synthase gene: a candidate gene for the y locus controlling the red fruit colour in pepper. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998;36:785–789. doi: 10.1023/a:1005966313415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huh JH, Kan BC, Nahm SH, Kim S, Ha KS, Lee MH, Kim BD. A candidate gene approach identified phytoene synthase as the locus for mature fruit color in red pepper (Capsicum spp.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001;102:524–530. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dominant orange allele in pepper. 5,440,069. United States; Patent. 1995

- 20.Cornelius PL, Taylor NL. Phenotypic recurrent selection for intensity of petal color in red clover. J. Hered. 1981;72:275–278. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stommel JR, Simon PW. Phenotypic recurrent selection and heritability estimates for total dissolved solids and sugar type in carrot. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1989;114:695–699. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sy O, Bosland PW, Steiner R. Inheritance of phytophthora stem blight resistance as compared to phytophthora root rot and phytophthora foliar blight resistance in Capsicum annuum L. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2005;130:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon PW, Wolff XY, Peterson CE, Kammerlohr DS, Rubatzky VE, Strandberg JO, Basset MJ, White JM. High carotene mass carrot population. HortSci. 1989;24:174–175. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang YQ, Yanagawa S, Sasanuma T, Sasakuma T. Orange fruit color in Capsicum due to deletion of capsanthin-capsorubin synthesis gene. Breed. Sci. 2004;54:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Uribe L, O’Connell MA. A root-specific bZIP transcription factor is responsive to water deficit stress in tepary bean (Phaseoulus acutifolius) and common bean (P. vulgaris). J. Exp. Botany. 2006;57:1391–1398. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornero-Mendez D, Minguez-Mosquera MI. Xanthophyll esterification accompanying carotenoid overaccumulation in chromoplasts of Capsicum annuum ripening fruits is a constitutive process and useful for ripeness index. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:1617–1622. doi: 10.1021/jf9912046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lancaster JE, Lister CE. Influence of pigment composition on skin color in a wide range of fruit and vegetables. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1997;122:594–598. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fornasiero RB, Bonatti PM. Pigment content and leaf plastid ultrastructure in the tomato mutant lutescent-2. J. Plant Phys. 1985;118:297–307. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(85)80189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butler L, Chang LO. Genetics and physiology of the xanthophyllous mutant of the tomato. Can. J. Bot. 1958;36:251–267. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fray RG, Grierson D. Identification and genetic analysis of normal and mutant phytoene synthase genes in tomato by sequencing, complementation and cosupression. Plant Mol. Biol. 1993;22:589–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00047400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown CR, Edwards CG, Yang CP, Dean BB. Orange flesh trait in potato: inheritance and carotenoid content. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1993;118:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popovsky S, Paran I. Molecular genetics of the y locus in pepper: its relation to capsanthin-capsorubin synthase and to fruit color. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000;101:86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronen G, Carmel-Goren L, Zamir D, Hirschberg J. An alternative pathway to β-carotene formation in plant chromoplasts discovered by map-based cloning of Beta and old-gold color mutations in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:11102–11107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190177497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouvier F, D’Harlingue A, Backhaus RA, Kumagai MH, Camara B. Identification of neoxanthin synthase as a carotenoid cyclase paralog. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:6346–6352. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beatty S, Nolan J, Kavanagh H, O’Donovan O. Macular pigment optical density and it’s relationship with serum and dietary levels of lutein and zeaxanthin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;430:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye X, Al-Babili S, Kloti A, Zhang J, Lucca P, Beyer P, Potrykus I. Engineering the provitamin A (beta-carotene) biosynthetic pathway into (carotenoid-free) rice endosperm. Science. 2000;287:303–305. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Ambrosio C, Giorio G, Marino I, Petrozza A, Salfi L, Stiglianai AL, Cellini F. Virtually complete conversion of lycopene into β-carotene in fruits of tomato plants transformed with the tomato lycopene β-cyclase (tlcy-b) cDNA. Plant Sci. 2004;166:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewinsohn E, Gijzen M. Phytochemical diversity: the sounds of silent metabolism. Plant Sci. 2009;176:161–169. [Google Scholar]