Abstract

Background

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a deadly demyelinating disease of the brain, caused by reactivation of the polyomavirus JC (JCV). PML has classically been described in individuals with profound cellular immunosuppression such as patients with AIDS, hematological malignancies, organ transplant recipients or those treated with immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory medications for autoimmune diseases.

Methods and case reports

We describe five HIV seronegative patients with minimal or occult immunosuppression who developed PML including two patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, one with untreated dermatomyositis, and two with idiopathic CD4+ T cell lymphocytopenia. We performed a review of the literature to find similar cases.

Results

We found an additional 33 cases in the literature. Of a total of 38 cases, seven (18.4%) had hepatic cirrhosis, five (13.2%) had renal failure, including one with concomitant hepatic cirrhosis, two (5.2%) were pregnant women, two (5.2%) had concomitant dementia, one (2.6%) had dermatomyositis and 22 (57.9%) had no specific underlying diagnosis. Among these 22, five (22.7%) had low CD4+ T cell counts (0.080–0.294×109/L) and were diagnosed with idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia, and one had borderline CD4+ T cell count of 0.308×109/L.

The outcome was fatal in 27/38 (71.1%) cases within 1.5–120 months (median 8 months) from onset of symptoms, and 3/4 cases who harbored JCV-specific T cells in their peripheral blood had inactive disease with stable neurological deficits after 6–26 months of follow up.

Discussion

These results indicate that PML can occur in patients with minimal or occult immunosuppression and invite us to revisit the generally accepted notion that profound cellular immunosuppression is a prerequisite for the development of PML.

Keywords: immunosuppression, immunocompetent, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, JC virus, idiopathic CD4+ T cell lymphocytopenia

BACKGROUND

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is an often lethal demyelinating disease of the brain, caused by the human polyomavirus JC (JCV).[1] Approximately 85% of the adult population has antibodies against JCV and primary infection is asymptomatic. A profound suppression in cellular immunity has classically been recognized as the absolute requirement for reactivation of JCV, which subsequently can spread to the central nervous system and cause lytic infection of oligodendrocytes, leading to PML. Nowadays, approximately 79% of PML patients have AIDS, 13% have hematological malignancies, 5% are organ transplant recipients and 3% have autoimmune diseases treated with immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory medications.[2]

However, PML may also occur in patients with minimal or occult immunosuppression, which makes diagnosis particularly challenging. We now describe five cases of PML and performed a review of the literature on this topic, which revealed 33 other cases.[3–32] Altogether, these 38 cases invite us to revisit the generally accepted notion that severe immunodepression is an absolute prerequisite for the development of PML.

METHODS

We used the following search terms in PUBMED to find PML cases with minimal or occult immunosuppression: PML, JC virus and immunosuppresion, immunocompetent, case reports, primary or spontaneous PML and idiopathic CD4+ T- cell lymphocytopenia. Cases were excluded if the patient had HIV-infection, hematological disease (leukemias, lymphomas, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, Wiskot-Aldrich syndrome, common variable immunodeficiency, hypogammaglobulinemias), ongoing cancer, received recent chemotherapy, had auto-immune disease treated with oral or parenteral immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory medications or if the patient was a transplant recipient. We also excluded patients with untreated systemic lupus erythematosus or granulomatoses (tuberculosis and sarcoidosis). Cases were also excluded when diagnosis of PML led to the concomitant or subsequent discovery of a disease with known association with PML or when other opportunistic infections or tumors were present. Remaining cases were included only if PML was confirmed by positive JCV PCR in CSF, or characteristic features of PML on biopsy or autopsy. Using these criteria we could identify another 33 cases. Detection of JCV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in blood in 4 out of our 5 cases was performed as previously described.[33]

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 50-year-old man with history of alcoholic cirrhosis and esophageal varices presented with difficulties speaking, gait unstability and blurred vision. He had discontinued alcohol consumption 3 years prior and was not taking any medication. The neurological exam showed severe dysarthria and scanned speech, horizontal nystagmus and bilateral saccadic pursuit. Reflexes were increased in the left upper extremity, and he had bilateral dysmetria and gait ataxia. Vibration sense was decreased in both feet. An MRI of the brain showed a 2 cm area of hyperintensity on FLAIR images in the left brachium pontis, extending into the left cerebellar hemisphere, a smaller lesion in the right cerebellar hemisphere and one lesion in the right corona radiata. There was no mass effect or contrast enhancement in T1-weighted images. He had mild leukopenia at 3.5×109/L (51.5% neutrophils, 33.1% lymphocytes, 11.6% monocytes, 3.2% eosinophils), platelets were decreased at 70×109/L, and liver function tests were normal. HIV serology was negative and T cell subset analysis showed CD4+ count of 0.472×109/L and CD8+ count of 0.222×109/L with a CD4/CD8 ratio of 2.12. CSF exam showed 0 WBC and 0 RBC, concentration of protein was 280 mg/L and glucose 3.05 mmol/L. PCR for JCV DNA was negative in CSF. However, because of the clinical and radiological presentation, PML was suspected and the patient was treated with mirtazapine 15 mg/day.[34] Two months later, a repeat MRI showed an increase in size of the cerebellar lesions in FLAIR and there was no enhancement in T1-weighted images after administration of gadolinium (Figure 1A and B). JCV PCR was negative again in a second CSF sample. Brain biopsy of the right frontal lobe lesion confirmed the diagnosis of PML by positive immunohistochemistry (IHC) for JCV proteins and quantified PCR on fresh frozen brain sample showed a JC viral load of 3.96 × 107 copies/µg brain DNA. JCV specific T cells were detectable in his blood. His condition stabilized and a follow up MRI 8 months later showed transient speckled contrast enhancement of the lesions. Twenty-six months after onset of symptoms, he still has a persistent bilateral cerebellar syndrome. His current CD4+ T cell count is 0.730×109/L.

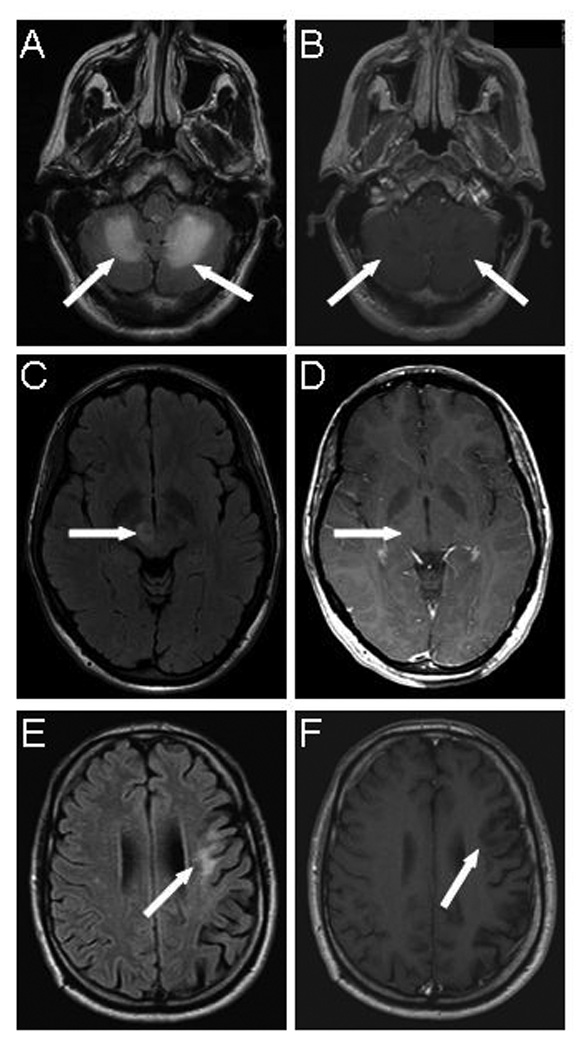

FIGURE 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of PML lesions in HIV-negative patients with minimal or occult immunosuppression. (cases 1, 3 and 4)

A) FLAIR image of patient with alcoholic cirrhosis (case 1) shows hyperintense bilateral cerebellar lesions ( arrows) which appear hypointense and do not display contrast enhancement on T1-weighted image (B, arrows).

C) FLAIR image of patient with dermatomyositis (case 3) shows hyperintense right thalamic lesion (arrow), which is isointense and does not enhance on post gadolinium T1 weighted image (D, arrow)

E) Flair image of patient with CD4+ T cell lymphopenia (case 4) show left frontal hyperintense lesion (arrow), which is hypointense and devoid of contrast enhancement on T1-weighted image (F, arrow)

Case 2

A 64-year-old man with history of alcoholic cirrhosis and eosophageal varices presented with left facial tingling and numbness, followed by one-month history of progressive left-sided weakness. He had been sober for one month. An MRI of the brain showed right parietotemporal and frontotemporal hyperintense lesions on FLAIR images. CSF exam was normal, but JCV PCR was not performed. WBC count was 9.400×109/L with 90.6 % neutrophils, 3.8% lymphocytes, 3.3 % monocytes, 0.3% eosinophils, 0.1% basophils. A right thalamic brain biopsy was complicated by intraparenchymal hemorrhage with mass effect and dexamethasone treatment was initiated. Histological exam confirmed the diagnosis of PML and dexamethasone was quickly tapered off. HIV serology was negative and the CD4+ T cell count was 0.240×109/L. JCV specific T cells were detectable in his blood. A lumbar puncture demonstrated a JC viral load of 1285 copies/mL. He was started on mirtazapine 15 mg/day. After 2 months, a follow-up lumbar puncture showed a negative JCV PCR and a repeat CD4+ lymphocyte count was 0.732×109/L. Currently, 8 months after onset of symptoms, he has made a remarkable recovery with minimal residual left-sided hemiparesis.

Case 3

A 29-year-old woman, with history of dermatomyositis, previously treated with hydroxychloroquine for 4 weeks fourteen months prior, presented with left arm numbness and weakness, and left leg weakness. She was not taking any medication. The neurological exam showed a mild left hemiparesis. She had mild leukopenia with a WBC count of 3.9×109/L initially, which normalized at 4.9×109/L six days later. An MRI of the brain showed hyperintense signal in FLAIR sequences in the right thalamus, which remained isointense without enhancement in T1-weighted images after administration of gadolinium (Figure 1C and D). Another lesion was present in the right frontal lobe white matter. Because an inflammatory demyelinating disorder was suspected, she received 1 g of methylprednisolone IV/day for 5 days, which did not improve her symptoms. A deltoid muscle biopsy showed perivascular atrophy, T-cell macrovasculopathy and severe myopathic change. Two months later, she developed horizontal nystagmus, followed by diplopia and increased left-sided weakness. The neurological exam showed right III and VI cranial nerve paresis, a left cortical hand syndrome and left leg weakness. WBC count was 4.5×109/L. A repeat MRI did not show any new lesions. She again received methylprednisolone 1 g/day IV for 5 days, followed by oral prednisone. A complete work-up for malignancies, infectious and other auto-immune diseases was unrevealing. A stereotactic brain biopsy of the right thalamic lesion established the diagnosis of PML. Oral corticosteroids were tapered off and mirtazapine 15 mg/day was started. CD4+ T cell count was 0.559×109/L and HIV serology was negative. She had detectable JCV-specific T cells in her blood. Six months after onset of neurological symptoms, she had made a remarkable recovery of the right III and VI paresis, and had partial improvement of her left hemiparesis allowing her to walk unassisted. Her current WBC count is 4.2×109/L.

Case 4

A 49-year-old man without significant past medical history presented with slowly progressive word finding difficulties. On neurologic exam, he had an expressive aphasia. MRI of the brain showed hyperintense signal in FLAIR and corresponding hypointense signal in T1-weighted images in both frontal lobe subcortical white matter, which did not enhance after administration of gadolinium (Figure 1E and F). A biopsy of the left frontoparietal region established the diagnosis of PML. HIV serology was negative and HIV RNA was undetectable in his blood, but he had a low CD4+ count of 0.080×109/L and a CD8+ count of 0.5×109/L with a CD4/CD8 ratio of 0.16. Protein electrophoresis and bone marrow biopsy did not reveal a causative factor for the low CD4 count. Twenty months after onset of symptoms, the patient is still slowly worsening and has an expressive aphasia, apraxia and bilateral pyramidal syndrome. Repeat MRI showed progression of the lesions and atrophy of the left frontal lobe. JCV specific lymphocytes were detected in his blood and he was started on mirtazapine 15 mg/day.

Case 5

A 61-year-old man with a history of syphilis two years prior and psoriasis which was treated with topical corticosteroids, presented with progressive word finding difficulties and right-sided weakness. On neurological exam, he had expressive aphasia, right leg paresis and right arm paralysis. An MRI of the brain showed a left frontoparietal white matter lesion on T2-weighted images, which extended through the corpus callosum to the other hemisphere, and a small lesion in the left brainstem. There was no contrast enhancement or mass effect. HIV serology was negative. CSF exam was unrevealing, and JCV PCR was negative. However, a left frontal stereotactic biopsy, done four months after onset of symptoms, established the diagnosis of PML. Two months later, the patient was rehospitalised with an acute renal insufficiency and serum creatinine at 985.6 µmol/L (54.56–100.32). WBC count at that time was 6.17×109/L with 14.9% lymphocytes, and CD4+ count was 0.294×109/L. On ultrasound, he had bilateral hydronephrosis and a CT scan showed left ureteritis. Urine culture was negative and no treatment was given. Urine PCR showed JCV, but no BKV DNA. He underwent one hemodialysis treatment for hyperkaliemia, after which there was fast and spontaneous improvement of the kidney function. He was then started on interferon alpha 3×106 IU subcutaneously every two days as treatment for PML, which was continued for nine months. Now, 5 years after onset of symptoms, he has made a remarkable recovery and only has a discrete right arm paresis and word finding difficulties.

RESULTS AND REVIEW OF LITERATURE

We found 33 other cases of PML with minimal or occult immunosuppression published in the literature from 1966 to 2009 (Table 1). Of these, 14 were HIV seronegative, and 19 had not been tested (marked by an asterisk in Table 1), including 12 diagnosed with PML before the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in 1984.[3–32] There were five patients with kidney disease (#1–5) [4, 11, 14, 19, 20], five patients with liver disease (#5–8 and #10) [5, 13, 20, 27, 30], two pregnant women (#13–14) [22, 24], two patients with dementia (#15–16) [16, 32] and 20 other cases (#9, #11–12 and #17–33) [3, 6–10, 12, 15, 17, 18, 21, 23, 25–29, 31]. Of note, case #5 had kidney failure and liver cirrhosis, and is therefore counted once in each category. Among these 20 cases, 14 had normal or high WBC counts (# 9, #11–12, #19, # 20–21, # 24–29, #31 and #33), one had low total lymphocytes counts (#17) and four had low or borderline low CD4+ T cell counts (0.08–0.308×109/L) (#18, #22–23 and #30). One of these 20 cases gives no information about white blood cell count (# 32).

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of published PML patients with minimal or occult immunosuppression

| Case number Publication |

Patient characteristics Underlying disorder and PMH |

Symptoms and signs | Lab and CSF exam | Diagnosis | Treatment and outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Arai Y et.al., 2002[4] |

F 74, CRF, renal anemia | Gait disturbance, dysarthria | CSF protein 3.83 mmol/L | Autopsy | Death six months after admission (respiratory failure) |

| 2. Guillaume et.al 1999[11] |

M 65, renal failure and kidney stones * | Frontal headache, spatiotemporal disorientation and left hemiparesis |

CSF: normal | Biopsy | Cytarabine IV/IT Death seven months after onset of symptoms |

| 3. Irie et.al 1992[14] |

F 64, CRF, on hemodialysis for 6 years | Cerebellar syndrome and left IIIrd nerve paresis |

WBC 4.8×10^9/L, 16% lymphocytes. Impaired cell- mediated immunity, but normal CD4/CD8 ratio CSF protein : 5.72 mmol/L |

Autopsy | Death five months after onset of symptoms (sepsis) |

| 4. Matsubara et.al. 1984[19] |

M 56, CRF, on hemodialysis for 11 years * | Behavior change for 1 month, followed by speech disturbance, gait and left arm ataxia, dysphagia, facial asymmetry, and right ptosis |

CSF: normal | Autopsy | Death 5 months after onset of symptoms (sudden respiratory failure) |

| 5. Matsuda et.al., 2006[20] |

M 57, CRF on hemodialysis for 10 years, hepatitis C and liver cirrhosis, HTLV-1 uveitis |

Agnosia and disorientation, right hemiparesis, progressing to complete paralysis of both extremities |

WBC 2.6×10^9/L Normal CD4/CD8 ratio CSF: normal |

CSF JCV PCR Autopsy HTLV-1 myelopathy |

Death 7 months after admission (pneumonia) |

| 6. Hoogenraad et.al. 1996[13] |

M 62, chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis * | Confusion, aphasia and dementia | N/A | Biopsy | No information |

| 7. Anstrom K and Stoner G 1994[5] |

F 62, pleuritis 10 years prior * | Emaciated, icteric, subfebrile, ascites | WBC 13.400×10^9/L | Autopsy Laennec’s cirrhosis |

Death 7 weeks after admission |

| 8. Lima et.al. 2005[30] |

M 55, chronic hepatitis C diagnosed 4 years prior, start IFN-α and ribavarin 6 months prior |

Left homonymous hemianopsia and left hemiparesis |

WBC 3.6×10^9/L, CD4 0.144×10^9/L |

Biopsy | Death 7 months after onset of symptoms |

| 9. Ali Cherif et.al. 1983[27] |

F 59, chronic alcoholism * | Mental disorder, dysartria, hemiparesis, seizures |

CBC normal | Autopsy | Death 7 months after onset of symptoms (status epilepticus) |

| 10. Ali Cherif et.al. 1983[27] |

M 41, hemochromatosis* | Left hemiparesis, followed by right sided weakness, dysarthria, dysphagia |

CSF: normal CBC: normal |

Autopsy cirrhosis |

Death 7 months after onset of symptoms (pneumonia) |

| 11. Ali Cherif et.al. 1983[27] |

M 49 * | Behavioral changes, generalized hypertonia, followed by chorea, seizures |

CSF: normal CBC: normal |

Autopsy | Death 8 months after onset of symptoms |

| 12. Ali Cherif et.al. 1983[27] |

F 54 * | Meningitis, paralysis of pharyngeolaryngeal and respiratory muscles, flask quadriplegia, trismus |

CBC: normal CSF exam: WBC 270×10^6/L |

Autopsy | Death 1.5 months after onset of symptoms |

| 13. Stockhammer et.al. 2000[24] |

F 24 | Myoclonic jerks of the left hand, one month before pregnancy, with progressive worsening at 3 months of pregnancy and left hemiparesis at 7 months of pregnancy, followed by dysarthria, dysphagia, and tetraparesis |

CBC: normal CSF exam normal |

Biopsy | Methylprednisolone for suspected vasculitis with further worsening. Cytarabine IV after biopsy. Death 12 months after onset of symptoms |

| 14. Rosas et.al. 1999[22] |

F 21, pregnant, UTI and positive toxo serology on admission |

Progressive left hemiparesis, starting fifth month of pregnancy, cerebellar syndrome |

WBC 17.44×10^9/L 63.2% CD2 cells and 24.5% CD19 cells, CD4/CD8 2.3 CSF: normal |

Biopsy | Alive 16 months after onset of symptoms |

| 15. Kelleher et.al 1994[16] |

F 80, slowly progressive dementia for one year * |

Sudden change in rate and character of mental deterioration |

WBC 15.4×10^9/L, 12% lymphocytes |

Autopsy Alzheimer’s disease |

Death 6 weeks after onset of symptoms |

| 16. Alafuzoff et. al. 1999 [32] |

F 75 inactive tuberculosis, arthroplasty of the hip |

Fatigue, cognitive decline, cerebellar syndrome, followed by rigidity and left pyramidal syndrome |

WBC normal | Autopsy Alzheimer’s disease |

Death 13 months after onset memory impairment |

| 17. Takeda et.al. 2008[26] |

M 64, suspected hepatitis 25 years prior (hepatitis B and C antigens seronegative) * |

Vertigo and nausea progressing to left hemiparesis, urinary incontinence, cognitive dysfunction, visual disturbance and emotional instability |

WBC 4.2×10^9/L with 10% lymphocytes |

Autopsy | Death 11 months after onset of symptoms |

| 18. Chang et.al. 2007[29] |

M 57, Hepatitis B carrier | Seizure 3 months prior to admission Subacute behavioral problems and speech difficulties |

CBC: normal CD4+ count 0.308×10^9/ L CSF: normal |

Biopsy | Recombinant α2a interferon and IV cytarabine Death five months after seizure (pneumonia) |

| 19. Bhatia KP et.al. 1996[6] |

F 63 Hysterectomy * |

extrapyramidal syndrome x 5 y. Cognitive decline, visuomotor apraxia, visual agnosia, and dystonia x 2 y. Paranoia, hallucinations, right hemianopsia and right hemiplegia x 6 months |

CBC: normal CSF: normal cell count, oligoclonal IgG distribution |

Autopsy | Death 10 years after onset of symptoms |

| 20. Rockwell D et.al 1976[21] |

F 45, inactive pulmonary tuberculosis treated 16 years prior * |

progressive mental deterioration, right hemiparesis, seizures, aphasia |

Normal blood lymphocyte counts CSF protein 510 mg/L |

Biopsy | Cytarabine IV/IT, alive 20 months after discharge, despite progression |

| 21. Knight et.al 1988[17] |

M 68, psoriasis, bilateral parotid swelling due to sarcoid 14 years prior, excision of basal cell carcinoma and carcinoma of the sebaceous glands 3y prior with sarcoid in surrounding skin and lymph node |

Mild cognitive deficit, left hemiparesis and sensory deficit, left visual inattention |

CSF: normal Routine blood tests normal |

CSF JCV antibodies, Autopsy No sarcoidosis |

IV cytarabine Death 9 months after onset of symptoms (pneumonia) |

| 22. Hayashi Y et.al. 2008[12] |

M 71, Sjogren syndrome with interstitial pneumonia, chronic ischemic heart disease |

Dementia, right hemiparesis, ataxia, developed akinetic mutism after 3 months |

Normal WBC count with low percentage of lymphocytes CD4+ count 0.272/L ANA 1:1280 CSF: oligoclonal bands |

CSF JCV PCR, Biopsy |

Steroid pulse therapy Cytarabine iv, alive 18 months after onset of symptoms without improvement |

| 23. Rueger et.al. 2006[23] |

M 39 | Vertigo, progressive ataxia, slurred speech and diplopia |

Normal WBC count with 5% lymphocytes, CD4+ count 0.08×10^9/L, CD4/CD8 ratio 0.5 CSF protein 490 mg/L, oligoclonal banding |

CSF JCV PCR, biopsy |

Recovery of visual function, improvement of ataxia and cognition 20 months after onset of symptoms |

| 24. Zochodne et.al. 1987[25] |

F 70 * | Gait ataxia, dysarthria, dementia and weakness progressing over 43 months |

Normal WBC count | Autopsy | Death 43 months after onset of symptoms (pneumonia) |

| 25. Bolton et.al. 1971[7] |

M 40 * | Anxiety, psychomotor slowing, spasticity | Normal WBC count CSF exam: protein 720 mg/L, WBC 2×10^6/L, RBC 60×10^6/L |

Autopsy | Death 18 months after onset of symptoms (pneumonia) |

| 26. Isella et.al. 2005[15] |

M 65, chronic gastritis and hiatal hernia, coronary artery disease |

Fluctuating headache and personality changes for one month followed by progressive gait ataxia, psychomotor slowing and left hemiparesis |

Normal WBC count, 76% T cells, normal CD4/CD8 ratio CSF slightly traumatic |

CSF JCV PCR, Autopsy |

IV cidofovir, after 2 months interferon β IM was added Death 11 months after onset of symptoms (pneumonia) |

| 27. Faris et.al 1972[9] |

F 56 * | Compulsive eating disorder, blindness, ataxia, left hemiparesis |

Normal WBC count and differential CSF: WBC 68×10^6/L |

Autopsy | Death 22 months after onset of symptoms (pneumonia) |

| 28. Adair et.al. 1996[3] |

M 66 * | Altered speech and gait, tetraparesis with left facial droop, dementia |

Normal WBC count and differential CSF exam normal |

Autopsy | Death 8 months after onset of symptoms (aspiration pneumonia) |

| 29. Fermaglich et.al. 1970[10] |

M 46, possible schizophrenia, seizures two years prior, pneumonia, essential hypertension, skull fracture * |

Progressive left hemiparesis and sensory deficit, left inferior homonymous quadrantanopsia, seizures |

Normal routine laboratory tests | Autopsy Brain: cyst in superior parietal lobe |

Death 14 months after onset of symptoms (pneumonia and flebitis) |

| 30. Chikezie et.al. 1997[8] |

M 47, coronary artery disease | Confusion and dysphasia | CD4+ count < 0.1×10^9/L with CD4/CD8 ratio < 0.60 on two occasions, |

Biopsy | No information |

| 31. Lucena et.al. 2009[18] |

M 72, 40% body surface burn | Coma post cardiorespiratory arrest and sepsis |

During sepsis: total lymphocytes 3.7×10^9/L |

Autopsy | Death 50 days after suffering extensive burns |

| 32. Stam 1966[28] |

M * | Writing difficulties and slow tremor, episodes of paraesthesia, followed 8 years later by hemianesthesia, cognitive decline, aggressive behavior, cerebellar syndrome and left-sided weakness |

No information | Autopsy | Death 9 years after onset of symptoms |

| 33. Markiewicz et.al. 1977 [31] |

F 31 * | Seizures, hallucinations, memory disorders, subfebrile |

WBC 15.2×10^9/ L | Autopsy | Death 8 months after onset of symptoms |

PMH: past medical history, M: male, F: female, CRF: chronic renal failure, UTI: urinary tract infection, CBC: complete blood count, CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, IV: intravenously, IT: intrathecally,

HIV serology not available

Of a total of 38 cases, seven (18.4%) had hepatic cirrhosis, five (13.2%) had chronic renal failure, two (5.2%) were pregnant women, two (5.2%) had concomitant dementia, one (2.6%) had dermatomyositis and 22 (57.9%) had no specific underlying diagnosis. Among these 22, five (22.7%) had low CD4+ T cell counts (0.080–0.294×109/L) and were diagnosed with idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia. The outcome was fatal in 27/38 (71.1%) cases within 1.5–120 months from onset of symptoms (median 8 months).

DISCUSSION

The 38 patients reported in our series and in the review of the literature did not have classic risk factors for development of PML. Indeed, it is commonly thought that most PML patients have a severe deficit in cellular immunity. Furthermore, we and others have previously demonstrated that the cellular immune response, mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, plays a crucial role in the containment of JCV. However, transient or discrete failure in cellular immunity might be enough to promote JCV reactivation. Chronic disease such as hepatic cirrhosis, caused either by alcohol, hepatitis C infection or malnutrition, as well as kidney failure may cause immunosuppression.

Indeed, hepatic cirrhosis can lead to portal hypertension and hypersplenism, with subsequent leukopenia as white blood cells are sequestrated in the enlarged spleen. Furthermore, cirrhosis also leads to hypogammaglobulinemia. Cirrhosis was indeed the underlying condition in seven PML patients in our study and leukopenia, lymphocytopenia or CD4+ T lymphocytopenia was documented in three of them. It is well known that cirrhotic patients have a higher risk of developing bacterial infections and 30–50% of death among cirrhotic patients is directly caused by infections. Immune dysfunction in hepatic disease may be caused by altered cytokine production, impaired cellular immune response and vascular disturbances, which lead together to increased susceptibility to infections. (reviewed in [35])

Chronic renal failure has also been associated with immunosuppression and higher risk of infections. These patients have reduced responses to most vaccines incriminating T-cell dysfunction. In addition, hemodialysis patients have impaired lymphocyte proliferation and reduced production of activation-dependant cytokines in vitro possibly caused by deficient antigen-presenting cells. Furthermore, these patients have a marked decrease in IL-2 production, and an impaired T-cell proliferation. (reviewed in [36, 37]) Often, encephalopathic changes are thought to be caused by prolonged hemodialysis, but Matsubara et al. suggested that some of the cases of progressive dialysis encephalopathy might in fact be PML.[19] Of note, one patient with chronic renal failure was HTLV-I seropositive, but did not have Adult T cell leukemia (#5). Therefore, the contribution of HTLV-I infection to PML development remains unclear.

Our dermatomyositis patient (case 3) also illustrates the fact that rheumatological disease in and of itself can be a predisposition to develop PML, even in absence of immunosuppressive treatment. In a recent review of 36 PML patients with rheumatological diseases, only one with systemic lupus erythematosus had not been treated with any immunosuppressive medications.[38] Similarly, our patient had not been on any treatment for more than a year, contrary to other patients with dermatomyositis who developed PML while receiving immunosuppressive medications.[39, 40] Of note, she had a mild and transient leukopenia each time she presented with new neurological symptoms. However, her CD4+ T-cell counts were in the normal range at the time of PML diagnosis.

Interestingly, of these 38 patients with PML, 22 (57.9 %) had not been diagnosed with any specific underlying disease up to the development of PML. Among these, five patients were found to have idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia (ICL) (CD4+ count <0.300×109/L). One hepatitis B carrier had a borderline CD4+ count of 0.308×109/L. DeHovitz et al. reported that six out of 248 (2.4%) HIV seronegative sexually active women without history of IV drug use had transiently CD4+ T –cell counts of less than 0.35×109/L which normalized several months later. In a larger population of 633 women (92% of whom were black), 20% consistently had low total white blood cell counts and thus the authors speculate that at any given time 0.4 to 4.1% of these women would have low CD4+ T-cell counts.[41] Patients with ICL often are asymptomatic, but then suddenly develop an opportunistic infection. A thorough search must be done for associated disorders. Zonios et al. followed a cohort of 39 patients with ICL and found that 15 patients contracted an opportunistic infection and four developed an auto-immune disease upon follow-up.[42]

Pregnancy is a classic state of relative immunosuppression. Among seventy-one pregnant women, those who had an increase in their JCV and BKV antibody titer in the third trimester had lower lymphocyte counts. One can hypothesize that a decrease of the cellular immune response led to viral reactivation and subsequent rise of the humoral immune response in these women.[43] Interestingly the two pregnant women who developed PML did not have documented leukopenia.

Two 75–80 years old PML cases had Alzheimer disease as the sole predisposing disease. However, three other patients, aged 63–70, were clinically suspected to have a degenerative disease due to their age and clinical presentation (#19, #24 and #28). One can only speculate that age-associated immunosuppression allowed JCV reactivation in these cases. Of note, T cell subsets were not available.

There are several limitations to our study. First, 19 patients were not tested for HIV. It is therefore possible that some of these had unrecognized HIV-infection as predisposing factor for PML. However, it is unlikely since 12 of them were diagnosed with PML before the AIDS epidemic, 16 had an autopsy showing no features consistent with HIV-infection, and 14 had none of the typical hematological abnormalities of AIDS. Second, not all patients reported in Table 1 had a thorough work up to uncover causes of immunosuppression during their lifetime, since the diagnosis of PML was only established at autopsy in many of them. Third, T cell subsets were not available in 24 out of the 33 cases found in literature, and it is possible that the diagnosis of ICL was overlooked in several of these cases.

In conclusion, clinicians should be aware that PML can occur in patients with minimal or occult immunosuppression. In those patients, JCV CSF PCR is warranted if they have a progressive neurological disorder associated with non-enhancing brain lesions that do not respect vascular territories. If JCV PCR is negative, a brain biopsy should be performed to establish the diagnosis, as it was the case of our patient with alcoholic cirrhosis (case 1) and one of the patients with idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia (case 5)

There is no specific treatment for PML. Therefore, the most important therapeutic intervention is to identify, and if possible correct, the underlying cause of immunosuppression. In fact out of the four tested PML patients in this study, all were able to mount a detectable cellular immune response against JCV and three of them now have an inactive disease clinically and radiologically, 6–26 months from disease onset.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING

This study was supported in part by NIH grants R01 NS 041198 and 047029 and K24 NS 060950 to IJK, and T32 CA09031-32 to SG.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS: none

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC/WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS:

PML is considered a disease affecting severely immunosuppressed individuals. In this paper, we clearly demonstrate that severe immunosuppression is not a prerequisite to develop this disease. Although PML is a rare disease, clinicians must be aware that PML can be the cause of brain lesions, even in people who are considered healthy or have conditions that are not thought to be associated with severe immunological deficits.

COPYRIGHT LICENSE STATEMENT:

The corresponding author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry and any other BMJPGL products and to exploit all subsidiary rights as set out in our license.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy revisited: Has the disease outgrown its name? Ann Neurol. 2006;60(2):162–173. doi: 10.1002/ana.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koralnik IJ, Schellingerhout D, Frosch MP. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 14-2004. A 66-year-old man with progressive neurologic deficits. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(18):1882–1893. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc030038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adair JC, Schwartz RL, Eskin TA, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia: a clinicopathologic correlation. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1996;9(4):209–213. doi: 10.1177/089198879600900408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arai Y, Tsutsui Y, Nagashima K, et al. Autopsy case of the cerebellar form of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy without immunodeficiency. Neuropathology. 2002;22(1):48–56. doi: 10.1046/j.0919-6544.2001.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astrom KE, Stoner GL. Early pathological changes in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: a report of two asymptomatic cases occurring prior to the AIDS epidemic. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;88(1):93–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00294365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia KP, Morris JH, Frackowiak RS. Primary progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy presenting as an extrapyramidal syndrome. J Neurol. 1996;243(1):91–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00878538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolton CF, Rozdilsky B. Primary progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. A case report. Neurology. 1971;21(1):72–77. doi: 10.1212/wnl.21.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chikezie PU, Greenberg AL. Idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia presenting as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: case report. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(3):526–527. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faris AA, Martinez AJ. Primary progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. A central nervous system disease caused by a slow virus. Arch Neurol. 1972;27(4):357–360. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1972.00490160085012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fermaglich J, Hardman JM, Earle KM. Spontaneous progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1970;20(5):479–484. doi: 10.1212/wnl.20.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guillaume B, Sindic CJ, Weber T. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: simultaneous detection of JCV DNA and anti-JCV antibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid. Eur J Neurol. 2000;7(1):101–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi Y, Kimura A, Kato S, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia in a patient with Sjogren syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2008;268(1–2):195–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoogenraad TU, Jansen GH, van Hattum J. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(4):345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-4-199608150-00019. author reply 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irie T, Kasai M, Abe N, et al. Cerebellar form of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with chronic renal failure. Intern Med. 1992;31(2):218–223. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.31.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isella V, Marzorati L, Curto N, et al. Primary progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: report of a case. Funct Neurol. 2005;20(3):139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelleher MB, Galutira D, Duggan TD, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with Alzheimer’s disease. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1994;3(2):105–113. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199406000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knight RS, Hyman NM, Gardner SD, et al. Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy and viral antibody titres. J Neurol. 1988;235(8):458–461. doi: 10.1007/BF00314247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucena J, Girones X, Rico A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy--incidental finding in the forensic neuropathological examination. Clin Neuropathol. 2009;28(1):28–32. doi: 10.5414/npp28028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsubara O, Nakagawa S, Shinoda T, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with prolonged hemodialysis treatment. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1984;403(3):301–305. doi: 10.1007/BF00694906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuda H, Hayashi K, Meguro M, et al. A case report of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1-infected hemodialytic patient. Ther Apher Dial. 2006;10(3):291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rockwell D, Ruben FL, Winkelstein A, et al. Absence of imune deficiencies in a case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Am J Med. 1976;61(3):433–436. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosas MJ, Simoes-Ribeiro F, An SF, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: unusual MRI findings and prolonged survival in a pregnant woman. Neurology. 1999;52(3):657–659. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rueger MA, Miletic H, Dorries K, et al. Long-term remission in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy caused by idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia: a case report. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(7):e53–e56. doi: 10.1086/500400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stockhammer G, Poewe W, Wissel J, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy presenting with an isolated focal movement disorder. Mov Disord. 2000;15(5):1006–1009. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200009)15:5<1006::aid-mds1038>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zochodne DW, Kaufmann JC. Prolonged progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy without immunosuppression. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14(4):603–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda S, Yamazaki K, Miyakawa T, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy showing extensive spinal cord involvement in a patient with lymphocytopenia. Neuropathology. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2008.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali Cherif A, Delpuech F, Habib M, et al. [Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Clinical, CT scan and neuropathologic findings. Apropos of 4 cases] Rev Neurol (Paris) 1983;139(3):177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stam FC. Multifocal leuko-encephalopathy with slow progression and very long survival. Psychiatr Neurol Neurochir. 1966;69(6):453–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang YY, Lan MY, Peng CH, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in an immunocompetent Taiwanese patient. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106(2 Suppl):S60–S64. doi: 10.1016/s0929-6646(09)60355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lima MA, Auriel E, Wuthrich C, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy as a complication of hepatitis C virus treatment in an HIV-negative patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(3):417–419. doi: 10.1086/431769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markiewicz D, Adamczewska-Goncerzewicz Z, Dymecki J, et al. A case of primary form of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with concentric demyelination of Balo type. Neuropatol Pol. 1977;15(4):491–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alafuzoff I, Hartikainen P, Hanninen T, et al. Rapidly progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with substantial cell-mediated inflammatory response and with cognitive decline of non-Alzheimer type in a 75-year-old female patient. Clin Neuropathol. 1999;18(3):113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du Pasquier RA, Kuroda MJ, Zheng Y, et al. A prospective study demonstrates an association between JC virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and the early control of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 9):1970–1978. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elphick GF, Querbes W, Jordan JA, et al. The human polyomavirus, JCV, uses serotonin receptors to infect cells. Science. 2004;306(5700):1380–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.1103492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chavez-Tapia NC, Torre-Delgadillo A, Tellez-Avila FI, et al. The molecular basis of susceptibility to infection in liver cirrhosis. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14(28):2954–2958. doi: 10.2174/092986707782794041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Girndt M, Sester M, Sester U, et al. Molecular aspects of T- and B-cell function in uremia. Kidney Int Suppl. 2001;78:S206–S211. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.59780206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Girndt M, Sester U, Sester M, et al. Impaired cellular immune function in patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(12):2807–2810. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.12.2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calabrese LH, Molloy ES, Huang D, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatic diseases: evolving clinical and pathologic patterns of disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(7):2116–2128. doi: 10.1002/art.22657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tubridy N, Wells C, Lewis D, et al. Unsuccessful treatment with cidofovir and cytarabine in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with dermatomyositis. J R Soc Med. 2000;93(7):374–375. doi: 10.1177/014107680009300710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vulliemoz S, Lurati-Ruiz F, Borruat FX, et al. Favourable outcome of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in two patients with dermatomyositis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(9):1079–1082. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.092353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeHovitz JA, Feldman J, Landesman S. Idiopathic CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):1045–1046. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zonios DI, Falloon J, Bennett JE, et al. Idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia: natural history and prognostic factors. Blood. 2008;112(2):287–294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coleman DV, Gardner SD, Mulholland C, et al. Human polyomavirus in pregnancy. A model for the study of defence mechanisms to virus reactivation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983;53(2):289–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]