Abstract

Although other methods exist for monitoring gastrointestinal motility and contractility, this study exclusively provides direct and quantitative measurements of the forces experienced by an orally ingested pill. We report motive forces and torques calculated from real-time, in vivo measurements of the movement of a magnetic pill in the stomachs of fasted and fed humans. Three-dimensional net force and two-dimensional net torque vectors as a function of time data during gastric residence are evaluated using instantaneous translational and rotational position data. Additionally, the net force calculations described can be applied to high-resolution pill tracking acquired by any modality. The fraction of time pills experience ranges of forces and torques are analyzed and correlate with the physiological phases of gastric digestion. We also report the maximum forces and torques experienced in vivo by pills as a quantitative measure of the amount of force pills experience during the muscular contractions leading to gastric emptying. Results calculated from human data are compared with small and large animal models with a translational research focus. The reported magnitude and direction of gastric forces experienced by pills in healthy stomachs serves as a baseline for comparison with pathophysiological states. Of clinical significance, the directionality associated with force vector data may be useful in determining the muscle groups associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility. Additionally, the quantitative comparison between human and animal models improves insight into comparative gastric contractility that will aid rational pill design and provide a quantitative framework for interpreting gastroretentive oral formulation test results.

Keywords: drug delivery, gastric retention, gastrointestinal biophysics, pill science

The question of what forces a pill experiences in the gastric environment is of great importance to the rational design of pills that target drug delivery to the proximal gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Many therapeutic agents would benefit from increased residence time in the stomach and a number of gastroretentive techniques for prolonging gastric residence time have been devised and tested (1–3). The most prominent gastroretentive methods are density mismatching, geometry-based, and bioadhesive doses (1–3). By calculating the forces a pill experiences in human stomachs, in vitro models can be designed that will aid in predicting clinical success. The net force results in this study can also serve as baseline measurements for comparison with pathophysiological GI dysmotilities. The calculations can also be used to analyze differences in strength of gastric-emptying forces amongst age groups and patient populations useful for disease-specific oral dosage design. Additionally, understanding the quantitative relationships among small animal, large animal, and human gastric forces provided by this work will aid in the selection of animal models and in interpreting translational research results.

Previous methods of measuring gastric forces include manometry measurements, which can be made by placing a balloon catheter in the stomachs of patients and monitoring pressure. Vassallo et al. added a load cell to a balloon catheter to monitor load in the antegrade direction (4). Measurements were reported as the cumulative load experienced by the balloon over a period of 30 min and are the most closely related to the measurements made in our study (4). However, the measurements are made on a 2-cm-diameter balloon, which is far larger than a typical pill (4). Additionally, the balloon catheter is tethered and therefore unrepresentative of motive forces experienced by a pill (4).

Studies by Kamba et al. investigated the relationship between gastrointestinal contractility and pill crushing force by assessing the destruction of pills with varying moduli in healthy male subjects (5, 6). Magnetic tracking methods can also be used to assess crushing force, disintegration, and tablet breakability (7). The crushing force of the gastrointestinal tract is very useful for designing oral dosage forms. However, crushing force studies do not elucidate the net motive forces experienced by a pill.

Parkman and Jones have incorporated a miniaturized pressure sensor into a pill, which communicates real-time manometry and other data via radio telemetry during gastrointestinal transit (8). Although the manometry data alone does not yield force or torque data, forces and torques could be calculated and paired with the pill data given detailed position as a function of time measurements. Whereas manometry measures the total contractile action of the entire muscularis mucosae, the directional data associated with force measurements in the appropriate coordinate system could be used to evaluate the contractility of individually oriented muscle layers (e.g., circumferential or longitudinal).

Biomechanics testing and manometry have been employed to investigate the contractility and motility of stomach muscle (9–11). Biomechanical measurements give great insight into the operation of stomach muscle and manometry techniques yield quantitative information regarding local pressure changes during gastrointestinal contractions (9). However, net forces experienced by a pill result from the pressure differences across the surface of a pill, its interaction with the mucosal lining, and the gastrointestinal contents. All of these factors affect the motion producing forces experienced by pills in the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, monitoring the motion of pills in real time is important to the accurate determination of gastric motive forces.

The method we employed for calculating instantaneous net forces experienced by model pills in the stomach began by obtaining high-resolution pill-tracking data. A superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID), radiotelemetry, ultrasound, fluoroscopy, and gamma scintigraphy are all capable of providing high-resolution pill location as a function of time data (8, 11–15). All of the methods are high cost and all except SQUID require image analysis to extract position data (15, 16). Additionally, pill-tracking methods have primarily been used to determine gastrointestinal tract residence time. Recently, our group and others have reported measurements using inexpensive, highly accurate real-time magnetic tracking (17–20). We employed a Hall array sensor technology to inexpensively and noninvasively track the position and orientation of magnetic model pills within the stomachs of humans, rats, and dogs without anesthesia. Force calculations were made using the acquired position data. The same force calculation technique could be applied to similar data obtained by any methodology, including the ones listed above. Evaluating the force from pill motion enables us to answer the question of what forces a pill experiences in the stomach. The data provide a pill’s eye view of the stomach that serves as a platform for investigating basic gastroenterological questions of motility and contractility, as well as for establishing quantitative design criteria for gastroretentive dosage forms.

Results and Discussion

Pill-Tracking Analysis.

The motion of the model oral dosage forms in the stomachs of humans, dogs, and rats is governed by the net forces and torque it experiences. Gastric transit data provided the Lagrangian position of the magnetic model pill in three translational [x(t), y(t), z(t)] and two rotational [θ(t), φ(t)] coordinate planes at a rate of 10 Hz. In the human studies, the  corresponds to the cephalo-caudal,

corresponds to the cephalo-caudal,  to the dorsal-ventral, and

to the dorsal-ventral, and  to the lateral directions; whereas, in the animal studies,

to the lateral directions; whereas, in the animal studies,  corresponds to the dorsal-ventral,

corresponds to the dorsal-ventral,  to the cephalo-caudal, and

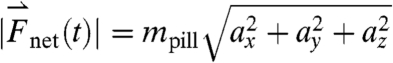

to the cephalo-caudal, and  to the lateral directions as plotted in Fig. 1A. The myoelectric slow wave that governs the frequency of gastric contractions occurs at 0.05–0.08 Hz in humans, dogs, and rats, indicating that 10 Hz data collection rate can be assumed to provide sufficient resolution for instantaneous velocity and acceleration calculations (6, 11, 17). We evaluated the instantaneous translational velocity components as Vx = dx(t)/dt, Vy = dy(t)/dt, Vz = dz(t)/dt, and the angular velocity components as νθ = dθ(t)/dt, νφ = dφ(t)/dt. Similarly, we evaluated the instantaneous acceleration (ax, ay, az, αθ, αΦ) of pill motion by evaluating corresponding instantaneous time derivatives of velocity components. Given the acceleration, magnitude of net force (

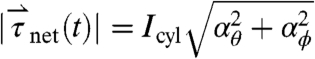

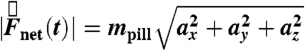

to the lateral directions as plotted in Fig. 1A. The myoelectric slow wave that governs the frequency of gastric contractions occurs at 0.05–0.08 Hz in humans, dogs, and rats, indicating that 10 Hz data collection rate can be assumed to provide sufficient resolution for instantaneous velocity and acceleration calculations (6, 11, 17). We evaluated the instantaneous translational velocity components as Vx = dx(t)/dt, Vy = dy(t)/dt, Vz = dz(t)/dt, and the angular velocity components as νθ = dθ(t)/dt, νφ = dφ(t)/dt. Similarly, we evaluated the instantaneous acceleration (ax, ay, az, αθ, αΦ) of pill motion by evaluating corresponding instantaneous time derivatives of velocity components. Given the acceleration, magnitude of net force ( ) at each time point was calculated using the equation

) at each time point was calculated using the equation  , in which mpill denotes the mass of the pill. The magnitude of net torque (

, in which mpill denotes the mass of the pill. The magnitude of net torque ( ) is calculated using the rotational equivalent of the force equation, in which the pill is approximated as a cylinder,

) is calculated using the rotational equivalent of the force equation, in which the pill is approximated as a cylinder,  , in which

, in which  .

.

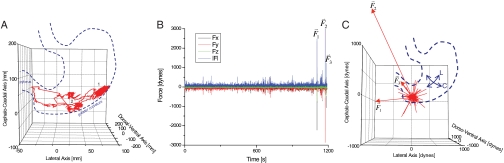

Fig. 1.

(A) The solid red line shows a three-dimensional trajectory plot of the model pill in an exemplary fasted human subject. A dashed, dark-blue outline of the frontal projection of the stomach is superimposed to correlate the pill motion with the anatomical position. The pill resides predominantly along the greater curvature of the stomach. At first, the pill resides more orally (position “1”) and at later times (position “2”) more aborally as expected. Ultimately, the pill is emptied through the pylorus into the small intestines. (B) Exemplary fasted human subject axial force components in three dimensions ( ,

,  , and

, and  ) showing no preference for the

) showing no preference for the  gravitational direction plotted with the magnitude of the net force vector (

gravitational direction plotted with the magnitude of the net force vector ( ) as a function of time. The three largest force vectors associated with gastric emptying are labeled

) as a function of time. The three largest force vectors associated with gastric emptying are labeled  ,

,  , and

, and  (2,481; 3,014; and 1,236 dynes, respectively). (C) Three-dimensional force vectors plotted with their origins at the position of the pill, corresponding with position 2 in the trajectory plot, as it moves during phase III of digestion (1,100–1,200 s). Propulsive forces

(2,481; 3,014; and 1,236 dynes, respectively). (C) Three-dimensional force vectors plotted with their origins at the position of the pill, corresponding with position 2 in the trajectory plot, as it moves during phase III of digestion (1,100–1,200 s). Propulsive forces  ,

,  , and

, and  generated by phasic contractions of the antrum are labeled and overlaid on a frontal projection of the stomach marked with a longitudinal (L) and circumferential (C) curvilinear coordinate system. The directions of

generated by phasic contractions of the antrum are labeled and overlaid on a frontal projection of the stomach marked with a longitudinal (L) and circumferential (C) curvilinear coordinate system. The directions of  ,

,  , and

, and  indicate that circumferentially oriented muscle fibers play a large role in the gastric emptying of the magnetic model pill.

indicate that circumferentially oriented muscle fibers play a large role in the gastric emptying of the magnetic model pill.

Force and Torque Analysis.

The translational components of force  ,

,  , and

, and  from the data acquired during one of the fasted human trials are plotted as a function of time in Fig. 1B. Although the gravitational field points in the

from the data acquired during one of the fasted human trials are plotted as a function of time in Fig. 1B. Although the gravitational field points in the  direction, the

direction, the  component follows the other force components with no significant differences in magnitude or timing. Because that holds true for all cases studied, the gravitational component, the weight of the pill, was not factored into calculations. For studies in which gravity pointed in a direction other than

component follows the other force components with no significant differences in magnitude or timing. Because that holds true for all cases studied, the gravitational component, the weight of the pill, was not factored into calculations. For studies in which gravity pointed in a direction other than  during testing, a Cartesian coordinate transformation was performed so that gravity was pointing in the

during testing, a Cartesian coordinate transformation was performed so that gravity was pointing in the  direction for data analysis. Data analyzed in this study were from healthy subjects, establishing the force experienced by pills under physiological conditions. In the event of gastrointestinal dysmotility, unusual force patterns along a particular axis could indicate pathophysiological neuromuscular activity of a particular layer of the muscularis mucosae. Specific knowledge of the muscle fibers implicated in a case of gastrointestinal dysmotility provided by force and torque modeling data may aid in diagnosis or in deciding the course of treatment. Additionally, the directionality of the force vector data is useful in analyzing the contributions of different layers of the muscularis mucosae to gastric emptying.

direction for data analysis. Data analyzed in this study were from healthy subjects, establishing the force experienced by pills under physiological conditions. In the event of gastrointestinal dysmotility, unusual force patterns along a particular axis could indicate pathophysiological neuromuscular activity of a particular layer of the muscularis mucosae. Specific knowledge of the muscle fibers implicated in a case of gastrointestinal dysmotility provided by force and torque modeling data may aid in diagnosis or in deciding the course of treatment. Additionally, the directionality of the force vector data is useful in analyzing the contributions of different layers of the muscularis mucosae to gastric emptying.

Three components of force and two components of torque constitute force and torque vectors. Small fluctuations in the magnitude of force and torque (< 250 dynes and < 100 dynes·cm, respectively) reflect small stomach wall movements and noise, as shown in Fig. 1 B and Fig. S1. In previous studies, Stathopoulos et al. (19) demonstrated that the dominant frequencies of pill movement unrelated to measurement noise match the respiration and heart rate. Large spikes in the magnitude of force and torque appearing approximately 1,100 s after dosing this particular fasted human correspond to the phasic contractions associated with gastric emptying that occur just before the pill exits the stomach through the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum, as shown in Fig. 1C. We report the maximum force and torque experienced by the model pills prior to exiting the stomach as the gastric-emptying force  and torque

and torque  in fasted and fed humans, dogs, and rats. Plotting the magnitude of the force and torque vectors (

in fasted and fed humans, dogs, and rats. Plotting the magnitude of the force and torque vectors ( and

and  ) as a function of time gives a pill’s eye view of the digestive forces experienced in the gastric environment (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1).

) as a function of time gives a pill’s eye view of the digestive forces experienced in the gastric environment (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1).

It is important to note that, in the fed state, the stomach is filled with partially digested food mixed with gastric secretions, i.e., chyme (21). In this case, the stomach contents have the properties of water. In the fed state, the presence of food increases the chyme viscosity (21–23). Experiments to determine the exact chyme viscosity are invasive and often involve aspiration of contents or excision of the region of the gastrointestinal tract in question. Such experiments would detract from the noninvasive nature of the study. Hence, in this study, the contribution from viscous force on the net force  was not evaluated.

was not evaluated.

Human Trials.

In the fasted state, pills are the only ingested solid stomach contents, therefore minimal muscular contractions occur until the migrating myoelectric complex (MMC) or “housekeeping” wave, which occurs approximately every 90 min in fasted humans and causes large spikes in force until the stomach is empty (24). Fig. 1 B and C depicts the components and magnitude of forces experienced by the magnetic pill over time. The highest magnitude gastric motive forces— ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively (note that the gravitational force in the z direction is always mg = 667 dynes)—occurring approximately 90 min after ingestion that directly precede gastric emptying are attributed to the migrating myoelectric complex (seen in Fig. 1B). Based on the force profile observed in Fig. 1B, the motive forces were overlaid onto the 3D trajectory of the pill onto a lateral projection of the human stomach during the time period that corresponds to the MMC (1,100–1,200 s). Although the majority of the low-magnitude forces have randomly distributed orientations, the highest magnitude forces

, respectively (note that the gravitational force in the z direction is always mg = 667 dynes)—occurring approximately 90 min after ingestion that directly precede gastric emptying are attributed to the migrating myoelectric complex (seen in Fig. 1B). Based on the force profile observed in Fig. 1B, the motive forces were overlaid onto the 3D trajectory of the pill onto a lateral projection of the human stomach during the time period that corresponds to the MMC (1,100–1,200 s). Although the majority of the low-magnitude forces have randomly distributed orientations, the highest magnitude forces  ,

,  , and

, and  are oriented aborally while the pill is in the vicinity of the pyloric sphincter. In accordance with GI transit, the final large magnitude force

are oriented aborally while the pill is in the vicinity of the pyloric sphincter. In accordance with GI transit, the final large magnitude force  prior to gastric emptying is aligned with the projected opening of the pyloric sphincter. In the exemplary fasted human data plotted in Fig. 1C, the largest magnitude force vectors point primarily along the cephalo-caudal and dorso-ventral axes. Motive forces in the cephalo-caudal direction are likely associated with contractions of the circumferentially oriented muscularis mucosae. In the fasted state, because motion of the dense magnetic pills is inertially dominated, the motive forces are assumed to occur from solid-body motion rather than motion of the gastric contents. Therefore, in the fasted state, analysis of the 3D force vectors calculated from data collected by any high-resolution pill-tracking data in a gastric dysmotility patient could help to distinguish if the force profile along a particular axis is diminished or if all forces are diminished compared to healthy subjects to differentiate between weakening of muscle fibers in a particular orientation or of the muscularis as a whole.

prior to gastric emptying is aligned with the projected opening of the pyloric sphincter. In the exemplary fasted human data plotted in Fig. 1C, the largest magnitude force vectors point primarily along the cephalo-caudal and dorso-ventral axes. Motive forces in the cephalo-caudal direction are likely associated with contractions of the circumferentially oriented muscularis mucosae. In the fasted state, because motion of the dense magnetic pills is inertially dominated, the motive forces are assumed to occur from solid-body motion rather than motion of the gastric contents. Therefore, in the fasted state, analysis of the 3D force vectors calculated from data collected by any high-resolution pill-tracking data in a gastric dysmotility patient could help to distinguish if the force profile along a particular axis is diminished or if all forces are diminished compared to healthy subjects to differentiate between weakening of muscle fibers in a particular orientation or of the muscularis as a whole.

When fed, the ingested food undergoes muscular contractions for a greater portion of the gastric residence time of the pill, while the food grinds and mixes until it has been sufficiently digested to pass through the pyloric sphincter. In the human gastric environment, the time fraction histogram of the magnitude of force ( ) suggests that the MMC wave accounts for a small fraction of the total gastric residence time in the fasted state (24). When fed, the time fraction

) suggests that the MMC wave accounts for a small fraction of the total gastric residence time in the fasted state (24). When fed, the time fraction  histogram indicates a greater percentage of time spent in digestive contractions that produce forces higher than biorhythms in the fasted state. The motive forces experienced by the model pills are in the low range (< 3% of the weight of the pill, where the gravitational force in the z direction is mg = 667 dynes) during 94.5 ± 1.9% of the gastric residence time in the fasted state and 68.3 ± 12.1% in the fed (Fig. 2A). Torque (

histogram indicates a greater percentage of time spent in digestive contractions that produce forces higher than biorhythms in the fasted state. The motive forces experienced by the model pills are in the low range (< 3% of the weight of the pill, where the gravitational force in the z direction is mg = 667 dynes) during 94.5 ± 1.9% of the gastric residence time in the fasted state and 68.3 ± 12.1% in the fed (Fig. 2A). Torque ( ) histograms are statistically similar in the fasted and fed states indicating that the presence of food minimally affects the rotational forces experienced by the pills (Fig. 2A).

) histograms are statistically similar in the fasted and fed states indicating that the presence of food minimally affects the rotational forces experienced by the pills (Fig. 2A).

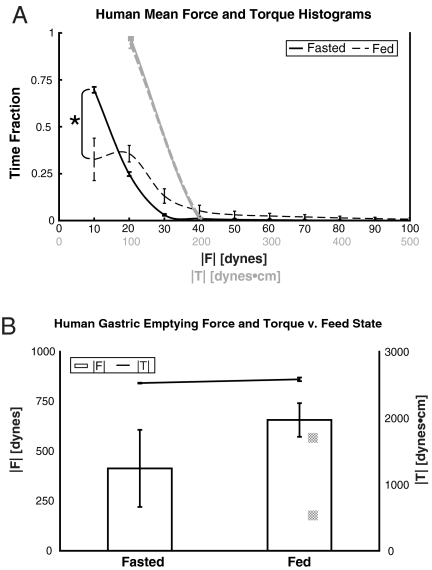

Fig. 2.

(A) Frequency histogram of the magnitude of force ( ) experienced by pills in the stomachs of fasted and fed human subjects (N = 3 each). In the fed state, the histogram curve shifts to the right reflecting greater time fraction of gastric residence that the pill experiences forceful contractions associated with the gastric grinding and mixing of ingested food (phase II and III of digestion). The * indicates p < 0.05 between the fasted and fed cases. Frequency histogram of the magnitude of torque (

) experienced by pills in the stomachs of fasted and fed human subjects (N = 3 each). In the fed state, the histogram curve shifts to the right reflecting greater time fraction of gastric residence that the pill experiences forceful contractions associated with the gastric grinding and mixing of ingested food (phase II and III of digestion). The * indicates p < 0.05 between the fasted and fed cases. Frequency histogram of the magnitude of torque ( ) experienced by pills in the stomachs of fasted and fed human subjects (N = 3 each) plotted in gray. No difference in torque distribution is observed between the fasted and fed states. (B) Plot shows the average maximum magnitude of force and torque experienced by the pills during gastric residence. The values correspond to the gastric-emptying forces experienced in phase III of digestion that lead to the passage of the pills from the stomach to the small intestines. No statistically significant difference appears between feed states in either force or torque, although there is a trend toward increased mean gastric-emptying force and torque in the fed state. All error bars depict the SEM.

) experienced by pills in the stomachs of fasted and fed human subjects (N = 3 each) plotted in gray. No difference in torque distribution is observed between the fasted and fed states. (B) Plot shows the average maximum magnitude of force and torque experienced by the pills during gastric residence. The values correspond to the gastric-emptying forces experienced in phase III of digestion that lead to the passage of the pills from the stomach to the small intestines. No statistically significant difference appears between feed states in either force or torque, although there is a trend toward increased mean gastric-emptying force and torque in the fed state. All error bars depict the SEM.

Although the time fraction  and

and  histograms describe the distribution of forces experienced by pills during the quiescent stages of digestion, quantifying the peristaltic forces and torques that lead to the ejection of the model pills from the stomach are of great utility to the assessment of gastric function and for the rational design of gastroretentive pills. The maximum force and torque experience during gastric residence is plotted in both the fasted and fed states in Fig. 2B. The average human gastric-emptying force (

histograms describe the distribution of forces experienced by pills during the quiescent stages of digestion, quantifying the peristaltic forces and torques that lead to the ejection of the model pills from the stomach are of great utility to the assessment of gastric function and for the rational design of gastroretentive pills. The maximum force and torque experience during gastric residence is plotted in both the fasted and fed states in Fig. 2B. The average human gastric-emptying force ( ) is 414 ± 194 dynes (62% of the weight of the pill) (N = 3) in the fasted state, which is statistically insignificantly lower than in the fed state, 657 ± 84 dynes (99% of the weight of the pill) (N = 3). Average human gastric-emptying torque shows a similar trend in that fasted and fed show little difference, 2,525 ± 5 and 2,582 ± 39 dynes·cm, respectively. The insignificant differences in fed and fasted gastric-emptying forces and torques in humans indicates that the motive forces exerted upon pills are similar in both the fasted and fed states. In light of the emptying force similarities and because the pills are too large to pass through the pyloric sphincter during the grinding and mixing of ingested food, the MMC wave is likely responsible for gastric emptying of the pills in both fasted and fed states.

) is 414 ± 194 dynes (62% of the weight of the pill) (N = 3) in the fasted state, which is statistically insignificantly lower than in the fed state, 657 ± 84 dynes (99% of the weight of the pill) (N = 3). Average human gastric-emptying torque shows a similar trend in that fasted and fed show little difference, 2,525 ± 5 and 2,582 ± 39 dynes·cm, respectively. The insignificant differences in fed and fasted gastric-emptying forces and torques in humans indicates that the motive forces exerted upon pills are similar in both the fasted and fed states. In light of the emptying force similarities and because the pills are too large to pass through the pyloric sphincter during the grinding and mixing of ingested food, the MMC wave is likely responsible for gastric emptying of the pills in both fasted and fed states.

For comparison with the uniaxial cumulative force results reported by Camilleri and Prather, calculated forces were normalized by the cross-sectional area of a sphere with equivalent volume to the pill (in the units of mechanical stress) (25). The average cumulative stress summed over the 30 min period prior to gastric emptying is 160,000 ± 70,000 dynes/cm2 fasted and 520,000 ± 270,000 dynes/cm2 fed, 42% and 1.5 times the cumulative uniaxial area-normalized forces (or stresses) measured by the force traction catheter, respectively. The area-normalized forces (or stresses) results from both studies demonstrate no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) and are therefore are in good agreement (24).

Dog Trials.

In the fasted and fed, force and torque histograms, no statistically significant difference is observed between the fasted and fed state (Fig. 3 A). One possible explanation for the observed lack of differentiation may be that the canine stomach is very muscular and the contractions are similarly forceful independent of the gastric contents (6, 25). In keeping with the supposition that the canine stomach undergoes very forceful digestive contractions, the average gastric-emptying force in the fasted state is 2,633 ± 78.7 dynes (3.95 times the weight of the pill) and in the fed state is 2,483 ± 161.5 dynes (3.73 times the weight of the pill). Average gastric-emptying force is 6% higher fasted than fed, and there is no statistically significant difference between the values. Also, no statistically significant difference is observed between the fasted and fed gastric-emptying torques, 2,610 ± 41.27 and 2,518 ± 12.77 dynes·cm, respectively. The lack of dependence of gastric-emptying force on feed state may be attributed to the nonerodible pill being large enough to require emptying by the MMC wave independent of feed state.

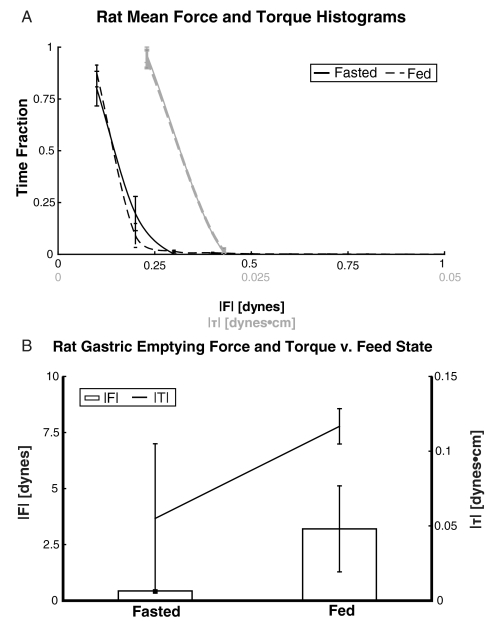

Fig. 3.

(A) Frequency histogram of the magnitude of force experienced by pills in the stomachs of fasted and fed canine subjects (N = 3 each). There is no appreciable difference in the magnitude of force distribution between the fasted and fed states. Frequency histogram of the magnitude of torque experienced by pills in the stomachs of fasted and fed canine subjects (N = 3 each) plotted in gray. No significant difference in torque distribution is observed between the fasted and fed states. (B) Although there is no statistically significant difference between feed states in either gastric-emptying force or torque, canine gastric-emptying forces are considerably higher than in the human in the fed state (p < 0.05). Additionally, the average coefficient of variance in the canine gastric-emptying forces is small (5%) compared to humans (30%). Error bars depict the SEM.

Rat Trials.

The mass of the model pills dosed to rats is much smaller than those dosed to humans and dogs due to differences in size. The presence of food had no significant affect upon the average fraction of gastric residence time spent in specific ranges of force or torque (Fig. 4). The average gastric-emptying force and torque experienced show a trend toward increasing in the fed state values, which are 7.4 and 2.1 times the fasted averages, respectively. The average gastric-emptying force is 0.43 ± 0.05 fasted (6% of the weight of the pill, mg = 6.8 dynes) and 3.2 ± 1.9 dynes (47% of weight of the pill) fed. The average gastric-emptying torque is 0.05 ± 0.05 fasted and 0.12 ± 0.01 dynes/cm fed (N = 2 fasted and N = 2 fed). Although there is a trend toward increasing gastric-emptying force and torque, it is not statistically significant.

Fig. 4.

(A) Frequency histogram of the magnitude of force experienced by pills in the stomachs of fasted and fed rats (N = 2 each). Feed state does not significantly affect the time fraction of force distribution. Frequency histogram of the magnitude of torque experienced by pills in the stomachs of fasted and fed rats (N = 2 each) plotted in gray. No difference in torque distribution is observed between the fasted and fed states. (B) Mean gastric-emptying force in rats is two orders of magnitude smaller than in humans and three orders of magnitude smaller than in dogs. However, pills dosed to rats are significantly smaller than those dosed to dogs and humans due to the relatively small size of rats. Trends toward increased gastric-emptying force and torque in the fed state are pronounced, but not statistically significant due to intersubject variability.

Interspecies Comparison and Implications.

Results indicate that fed dogs and humans produce statistically similar gastric-emptying forces and as such would be a significantly better preclinical model for gastroretentive dosage forms than rats. However, the fasted average canine gastric-emptying forces are roughly five times greater than those of human subjects indicating that, in the fasted state, canine stomachs may not provide a good gastric-emptying model for humans.

Because the dog and human model pills are identical, the comparison of forces and torques does not require size normalization. However, the rat model pills scale with the size of the animal and so, to compare the gastric environments, results were normalized by the cross-sectional area of spheres with equivalent volumes to the sphero-cylindrical pills to yield units of mechanical stress. Size-normalized gastric-emptying stresses in the fed rats are on the order of fed and fasted humans and an order of magnitude lower than dogs (Table 1). Fasted rats exhibit average normalized gastric-emptying forces an order of magnitude lower than humans and two orders of magnitude lower than dogs. Therefore, if rats are used as a preclinical gastric-emptying model for humans, it is likely best to perform experiments in the fed state. Fasted and fed dogs exhibit more similar gastric-emptying forces and torques to humans and dogs can accept human-size pills, therefore, although dogs exhibit higher gastric-emptying forces in general than humans, they are better preclinical models of human gastric emptying than rats.

Table 1.

Gastric-emptying forces and torques are directly comparable between canine and human studies because the pills used were identical

| Feed state and subject type | Area-normalized gastric-emptying force, dynes/sq cm | SEM | Area-normalized gastric-emptying torque, dynes/cm | SEM |

| Fasted humans | 606.0 | 283.8 | 3,700.9 | 8.0 |

| Fed humans | 962.4 | 123.7 | 3,783.4 | 38.9 |

| Fasted dogs | 3,857.7 | 115.3 | 3,824.4 | 60.5 |

| Fed dogs | 3,638.9 | 236.7 | 3,689.9 | 18.7 |

| Fasted rats | 48.2 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 5.6 |

| Fed rats | 355.7 | 213.1 | 13.0 | 1.3 |

Pills administered to rats are significantly smaller than those administered to dogs and humans. Therefore, gastric-emptying forces and torques were normalized by the cross-sectional area of a sphere with the same volume as the pill in the units of mechanical stress. In comparing the area-normalized gastric-emptying force (or stress) between rats and humans, although the dosage forms administered to rats are substantially smaller and have significantly lower mass, fed rats exhibit similar area-normalized forces to fasted humans.

Researchers and clinicians can utilize the force and stress calculations presented in this paper as quantitative guidelines for approaching the active research topic of achieving prolonged gastric residence time to improve the therapeutic benefit of pill-based therapies. It is important to note that the pills used in this study are models in that their size and mass approximate those typically dosed to humans, dogs, and rats. In the event that dosage forms or feeding conditions are altered from the standard, the method of using pill-tracking data to monitor force can be employed to calculate more accurate forces and stresses for those doses.

Discussion.

Monitoring inertial net forces in real time has been made possible by the advent of increasingly high-resolution pill-tracking methods including Hall array magnet position tracking and radiotelemetry. This manuscript presents a quantitative analysis of inertial net forces experienced by magnetic model pills during gastric residence in humans and two preclinical animal models both fasted and fed as tracked by Hall array sensors. Calculations of maximal force experienced in the stomach, or gastric-emptying forces, can serve as guidelines for the rational design of standard pill dosage forms as a guide for minimum hardness, frangibility, and crushing strength. The standard tablet parameters of crush strength and breakability can be easily tested against the in vivo force and torque data. The method and calculations could readily be applied to yield inertial force data for any oral dosage form in nearly any species, even if the pill differs significantly in size or mass from those reported in the study.

In particular, for pills designed to achieve increased gastric residence time, quantifying inertial forces is essential to the rational design of pills that will overcome gastric-emptying forces to remain in the stomach for extended periods of time. Gastroretentive pills have been investigated for decades because increasing the residence time of pills in the stomach would greatly benefit the numerous narrow absorption window therapeutics that are primarily absorbed in the proximal small intestines (1–3). Therefore, by retaining the pill in the stomach, proximal to the site of absorption, more of the drug could achieve uptake, and time-release formulations could be developed.

The most prevalent strategies for achieving gastric retention are density mismatching, geometry-based, and bioadhesive pills (1–3). The dense pill used in this study is an excellent model for dense pills that are meant to reside on the greater curvature of the stomach avoiding the pylorus for longer than pills that are of similar density to ingested food. Floating pills, another density mismatching technique, could be analyzed with the same technique by using less dense materials in pill fabrication and calculations and the gravitational component ( ) would be designed to be greater than the gastric-emptying force.

) would be designed to be greater than the gastric-emptying force.

Numerous swelling or unfolding pills have been developed with the intention of being easily swallowed and then changing shape upon introduction into the stomach such that they are too large to pass through the pyloric sphincter (1–3). For swelling tablets, the forces calculated in this manuscript could be used as a guideline in designing tablets with a sufficiently high compressive strength to overcome the gastric-emptying forces when swollen. Similarly, for unfolding films such as the Accordian Pill™, gastric-emptying forces can be used to inform the minimum bending modulus of the unfolded film necessary for gastric retention (26).

Finally, for bioadhesive dosage forms, the gastric-emptying forces calculated indicate how strong the tensile bioadhesive bond strength must be to achieve gastric retention (1–3). In bioadhesive doses, the cohesive strength of the loosely adherent mucus must also be taken into account (27).

In addition to pharmaceutical design, gastric net force calculations set forth in this manuscript can be used to assess gastrointestinal motility pathophysiologies and differences in gastric forces experienced by pills in different age groups or patient populations quantitatively. Patients with gastrointestinal dymostility, for example, may benefit from the forces calculated based on noninvasive high-resolution pill tracking to help pinpoint exactly where a loss of motility has occurred yielding atypically low forces in a particular region. GI net force calculations can also be used to assess the physiology of aging patients to investigate any correlation between age and the strength of gastric-emptying force, which could be of use to physiologists, physicians, and pharmaceutical scientists designing pills for diseases that afflict patient populations of a particular age group.

Conclusions

The net forces and torques, experienced by model pills in the stomach, can be calculated from position as a function of time data acquired by any modality. Forces and torques derived from the Motilis Magnet Tracking System data provide tremendous insight into the motive forces experienced by standard oral dosage forms. Analysis of the calculated forces yields a measure of gastric-emptying force experienced by pills that provides researchers and clinicians in the fields of gastric retention and gastroenterology a quantitative framework for designing gastroretentive pills and understanding their behavior in preclinical and clinical trials. From a clinical perspective, force and torque vectors calculated from high-resolution pill-tracking data provide directional data that relate to physiology or a suspected pathophysiology useful in diagnosing gastric dysmotility disorders and diseases. In the healthy fasted human subjects studied, the direction of the forces with the greatest magnitude all originate in the distal greater curvature of the antrum toward the pyloric sphincter, implicating primarily circumferential muscle fibers in gastric emptying. From a pharmaceutical research perspective, the gastric-emptying force and torque data can be used to estimate what bioadhesive or buoyancy force would be necessary to retain a dose within the stomach. Additionally, from a clinical perspective, force and torque monitoring provides magnitude and directional data that serve as a baseline for comparing with pathophysiologal digestive states.

Methods

Magnet Tracking System.

The tracking system consists of a pill containing a permanent magnet, a detection matrix (4·4 magnetic field sensors) and dedicated software implanted in a laptop computer (MTS-1, Motilis) (18). The tracking algorithm calculates the position and the orientation of the pill at 10 Hz, except the rotation around the magnetization axis (i.e., five degrees of freedom, three translations, and two rotations). The trajectory of the magnet was monitored and stored. Force data were calculated from position as a function of time data and the temporal distribution of force was analyzed.

Patients.

The size of the pills can be adapted to the size of the subject, which allows using the same approach for human, large animals, and rodents (17, 18). Pills containing magnets were either taken voluntarily by humans and dogs or by oral gavage for rats. The size and mass of the pills were Φ6.0 × 16 mm (740 mg, density of 1.75 g cm-3), Φ5.3 × 15 mm (530 mg, 1.8 g cm-3), and Φ0.85 × 1.1 mm (4.5 mg, 7.0 g cm-3), for human, dogs, and rats, respectively. The coating of the pill was Palaseal® for human and dogs and gold for rats. Experiments in fasted and fed states were carried out. Rat and canine subjects were confined to limit movement and pill tracking was performed without anesthesia. Human test subjects were seated in a semireclining position.

Three fed and three fasted human subjects ingested model nonerodible, rigid pills containing magnets per os. Four fed and four fasted Beagle dog subjects ingested the same model nonerodible, rigid pills as the human subjects. Additionally, two fed and two fasted Hooded Long Evans rat subjects were administered small cylindrical magnets that served as model oral dosages. For all subjects, the position of the magnet was monitored by the Motilis Magnet Tracking System. Force data were calculated from position as a function of time data and the temporal distribution of force was analyzed. All testing was performed in accordance with institutional animal care and use committee and institutional review board guidelines.

We report maximum forces and torques and analyzed as measures of the forces experienced during the peristaltic contractions that led to gastric emptying of a typical oral dosage form, termed gastric-emptying force and torque.

Statistical Analysis.

Comparisons between mean values of forces, torques, and stresses between feed states and amongst animals were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1002292107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bardonnet PL, Favre V, Pugh WJ, Piffaretti JC, Falson F. Gastroretentive dosage forms: Overview and special case of Helicobacter Pylori. J Control Release. 2006;111(1–2):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis SS. Formulation strategies for absorption windows. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10(4):249–257. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talukder R, Fassihi R. Gastroretentive delivery systems: A mini review. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2004;30(10):1019–1028. doi: 10.1081/ddc-200040239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vassallo MJ, Camilleri M, Prather CM, Hanson RB, Thomforde GM. Measurement of axial forces during emptying from the human stomach. Am J Phys. 1992;263(2):G230–G239. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.2.G230. Part 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamba M, Seta Y, Kusai A, Ikeda M, Nishimura K. A unique dosage form to evaluate the mechanical destructive force in the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Pharm. 2000;208(1–2):61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamba M, Seta Y, Kusai A, Nishimura K. Evaluation of the mechanical destructive force in the stomach of dog. Int J Pharm. 2001;228(1–2):209–217. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman K, et al. Assessing gastrointestinal motility and disintegration profiles of magnetic tablets by a novel magnetic imaging device and gamma scintigraphy. J Control Release. 2010;74(1):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkman HP, Jones MP. Test of gastric neuromuscular function. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1526–1543. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregersen H, Hausken T, Yang J, Odegaard S, Gilja OH. Mechanosensory properties in the human gastric antrum evaluated using B-mode ultrasonography during volume-controlled antral distension. Am J Physiol-Gastr L. 2006;290(5):G876–G882. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00131.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregersen H, Kassab G. Biomechanics of the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroent Motil. 1996;8(4):277–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.1996.tb00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hveem K, Sun WM, Hebbard GS, Horowitz M, Dent J. Insights into stomach mechanics from concurrent gastric ultrasound and manometry. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(4):1236–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen FN, et al. The use of gamma-scintigraphy to follow the gastrointestinal transit of pharmaceutical formulations. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1985;37(2):91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1985.tb05013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johannessen EA, Wang L, Reid SWJ, Cumming DRS, Cooper JM. Implementation of radiotelemetry in a lab-in-a-pill format. Lab Chip. 2006;6(1):39–45. doi: 10.1039/b507312j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao SSC, Lu C, SchulzeDelrieu K. Duodenum as an immediate brake to gastric outflow: A videofluoroscopic and manometric assessment. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(3):740–747. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weitschies W, Kosch O, Monnikes H, Trahms L. Magnetic marker monitoring: An application of biomagnetic measurement instrumentation and principles for the determination of the gastrointestinal behavior of magnetically marked solid dosage forms. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2005;57(8):1210–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andra W, et al. A novel method for real-time magnetic marker monitoring in the gastrointestinal tract. Phys Med Biol. 2000;45(10):3081–3093. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/10/322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guignet R, Bergonzelli G, Schlageter V, Turini M, Kucera P. Magnet tracking: A new tool for in vivo studies of the rat gastrointestinal motility. Neurogastroent Motil. 2006;18:472–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiroz P, Schlageter V, Givel J-C, Kucera P. Colonic movements in healthy subjects as monitored by a Magnet Tracking System. Neurogastroent Motil. 2009;21(8):837–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stathopoulos E, Schlageter V, Meyrat B, de Ribaupierre Y, Kucera P. Magnetic pill tracking: A novel non-invasive tool for investigation of human digestive motility. Neurogastroent Motil. 2005;17:148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weitschies W, Kotitz R, Trahms L, Cordini D. Gastrointestinal transit of a magnetically marked capsule monitored using a 37-channel SQUID-magnetometer. J Phys IV. 1997;7(C1):667–668. doi: 10.1021/js970185g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller LJ, Go VLW, Malagelada JR. Effect of individual chyme components on gastric-secretion and emptying after a meal. Gastroenterology. 1978;74(5):1068–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amidon GL, Debrincat GA, Najib N. Effects of gravity on gastric-emptying, intestinal transit, and drug absorption. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31(10):968–973. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1991.tb03658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillard S, Krishnan S, Udaykumar HS. Mechanics of flow and mixing at antroduodenal junction. World J Gastroentero. 2007;13(9):1365–1371. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i9.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bortolotti M, et al. The interdigestive migrating motor complex (IMMC) in idiopathic chronic gastric retention. Gastroenterology. 1983;84(5):1112–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camilleri M, Prather CM. Axial forces during gastric-emptying in health and models of disease. Digest Dis Sci. 1994;39(12) Suppl. S:S14–S17. doi: 10.1007/BF02300361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagan L, et al. Gastroretentive accordian pill: Encancement of riboflavin bioavailaility in humans. J Control Release. 2006;113(3):208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laulicht B, Cheifetz P, Tripathi A, Mathiowitz E. Are in vivo gastric bioadhesive forces accurately reflected by in vitro experiments? J Control Release. 2009;134(2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.