Abstract

When a child has a chronic illness, it is readily apparent that the family and school must enter into a partnership to assure that the educational needs of the child are being met. A family–school partnership, however, may also be important to address the needs of siblings of children with chronic illness. Siblings of children with diseases such as cancer are often highly distressed and may experience decrements in academic achievement within 2 years of diagnosis. Teachers and classroom peers may be a valuable source of support to these children. This manuscript documents the mental health needs of siblings of children with cancer, describes their perceptions regarding amount of social support received and importance of social support across home and school sources, and reveals important associations between social support and more positive emotional, behavioral, and academic functioning. These findings suggest that family–school partnerships may be valuable to address the mental health needs of siblings of children with cancer.

Keywords: Siblings of children with chronic illness, Social support, Family–school partnerships

Introduction

Each year 14,000 children in the United States are diagnosed with cancer (Ries et al., 2008). The disruption and turmoil created by these cancers reach beyond the diagnosed child to impact the entire family. Parents become highly distressed and their need to attend to the ill child at the hospital or at home may make them physically and emotionally unable to fully attend to the needs of their healthy children (Alderfer & Kazak, 2006). It is no surprise, then, that siblings within these families are at risk for emotional, behavioral, and academic problems (Alderfer et al., 2010). Given the level of disruption that childhood cancer causes for families, it is important to understand the consequences of these diseases for siblings and develop feasible interventions to reduce their distress and promote their adjustment. Finding innovative ways to bolster the social support received by these siblings, potentially through family–school partnerships, may help address sibling psychosocial distress and foster their resilience and mental health.

Siblings of children with cancer experience feelings of loss, fear, grief, shock, helplessness, insecurity, loneliness, jealousy, anger, and guilt (McGrath, 2001; Nolbris, Enskar, & Hellstrom, 2007; Patterson, Holm, & Gurney, 2004; Woodgate, 2006). When research studies report averaged depression or anxiety scores across samples of siblings, these powerful negative emotional reactions do not manifest as clinically elevated mean scores (e.g., Dolgin et al., 1997; Houtzager, Grootenhuis, Caron, & Last, 2004); however, there is some evidence that siblings of children with cancer fall into the clinical ranges of anxiety and depression at rates greater than the general population (Barrera, Chung, Greenberg, & Fleming, 2002; Cohen, Friedrich, Jaworski, Copeland, & Pendergrass, 1994; Houtzager et al., 2004; Sahler et al., 1994; Sloper & While, 1996). Furthermore, cancer-related distress in the form of posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptoms is emerging as a concern for a sizeable subset of siblings of children with cancer. Studies examining PTS reactions in siblings conclude that 29–38% exhibit moderate to severe cancer-related posttraumatic stress even years after cancer treatment has ended (Alderfer, Labay, & Kazak, 2003; Packman et al., 1997, 2004a, b).

Among the few studies investigating factors influencing the adjustment of siblings of children with cancer, social support has emerged as an important construct. Social support is an individual’s perception that he or she is cared for, esteemed, and valued by those in their social network. Social support has been demonstrated to enhance personal functioning, assist in coping adequately with stressors, and buffer one from adverse outcomes (Dubow, Tisak, Causey, Hryshko, & Reid, 1991; Malecki & Demaray, 2002; Weigel, Devereux, Leigh, & Ballard-Reisch, 1998). Social support across sources has been found to relate to better psychological adjustment (Demaray & Malecki, 2002a; Stewart & Sun, 2004), and more specifically, better adjustment to stressful events for school-aged children (Demaray, Malecki, Davidson, Hodgson, & Rebus, 2005; Jackson & Frick, 1998; Newman, Newman, Griffen, O’Connor, & Spas, 2007; Printz, Shermis, & Webb, 1999; Ystgeerd, 1997). Among siblings of children with cancer, Carpenter and Sahler (1991) found that siblings who report feeling ignored, unwanted, and misunderstood were more likely to have adjustment difficulties. Similarly, Sloper and While (1996) found that siblings who reported that the cancer caused them to lose the attention of their parents and others (e.g., “Since my brother/sister was diagnosed, people don’t care how I feel”) were more likely to show behavioral adjustment problems. Additionally, Barrera et al. (2004) found that siblings with high levels of social support compared to those with low levels had significantly fewer self- and parent-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, and behavioral problems.

The family is the primary social support system of children and adolescents (Newman et al., 2007), and greater family support has consistently been associated with less psychological distress and behavioral maladjustment (DuBois, Felner, Meares, & Krier, 1994; Kostelecky & Lempers, 1998; Newman et al., 2007). However, social support from friends, classmates, and teachers is also important (Demaray et al., 2005; Demaray & Malecki, 2002b; Newman et al., 2007; Torsheim, Aaroe, & Wold, 2003). Social support from friends or classmates has been found to significantly predict emotional adjustment and resilience and relate negatively to anxiety, social stress, depression, and behavioral maladjustment (Demaray & Malecki, 2002a, b; Stewart & Sun, 2004). Social support from teachers also relates positively to the emotional adjustment of children and adolescents (Demaray & Malecki, 2002a; Natvig, Albrektsen, & Qvarnstrom, 2003; Stewart & Sun, 2004). Zero-order correlations between indices of teacher support and measures of problem behavior, externalizing and internalizing symptoms and adaptive skills are of similar magnitude to those of parental support (Demaray & Malecki, 2002a). Furthermore, support from parents, teachers, and others in the school have been linked to school-related functioning (Demaray & Malecki, 2002b).

In an effort to determine if family–school partnerships might be of value in meeting the mental health needs of siblings of children with cancer, this research study had three aims: (a) document the emotional and behavioral needs of a sample of school-aged siblings of children with cancer; (b) describe and compare siblings’ perceptions of amount of support and importance of support across parents, teachers, close friends, classmates, and others in their schools; and (c) provide evidence of the associations between social support and emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes for siblings of children with cancer. Based upon past research, we hypothesized that the percentage of siblings falling into the borderline/clinical ranges on measures of psychosocial adjustment would be greater than that expected in the general population; that ratings of amount and importance of social support would vary across sources; and that greater amounts of social support would be related to more positive functioning.

Method

Participants

As part of a program of research and spanning two projects, 161 siblings of children with cancer and one of their parents (145 mothers, 16 fathers) provided data (79% enrollment rate). For 51 of the participating siblings, teachers also provided data. Siblings ranged in age from 8 to 18 with an average age of 12.6 (SD = 2.9) and roughly half of the sample was female (n = 77; 48%). Participating parents were in their early to mid forties (M = 41.3, SD = 5.8). Most of the participants were Caucasian/not Hispanic (86%) with 9% identifying as black or African American/not Hispanic. Annual household income ranged from less than $50,000 (22%) to more than $100,000 (41%), with the remainder of families reporting incomes between $50,000 and $100,000. The children with cancer were 3.7 to 38.0 months (M = 16.7 months; SD = 6.9) postdiagnosis and averaged 11.1 years of age (SD = 5.4); 62% of the siblings in our sample were older than the child with cancer. Cancer diagnoses included hematological malignancies (34% leukemias; 15% lymphomas); solid tumors (36%); brain tumors (13%); and other (2%).

Procedure

The following procedures were approved by our hospital’s institutional review board. To identify potential participants, researchers reviewed the tumor registry of a Cancer Center at a large eastern children’s hospital. Families with a child diagnosed with cancer or a brain tumor were eligible for participation if they were receiving cancer or cancer-like treatment (e.g., radiation, chemotherapy) or, if off treatment, were within 2 years of receiving the diagnosis. These families were sent a letter of invitation. They were then contacted by phone to learn if they had a healthy child in the home between the ages of 8 and 18 and to finalizing eligibility. During these phone calls, the study was explained, any questions were answered, and home visits were scheduled with those eligible families interested in participating. During the home visits parental informed consent and child assent were obtained and data were collected. One parent from each family and the target sibling completed a battery of measures and provided consent to contact the sibling’s teacher(s). Teachers were then contacted and asked to complete the Academic Competence Evaluation Scales regarding the sibling. Families received $50 to thank them for their participation.

Measures

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001)

This 120-item parent completed checklist provides ratings of a child’s competencies and behavioral/emotional problems. The first seven multipart items focus on the child’s participation in activities, performance in school, and involvement with friends. The remaining 112 items capture problem behaviors and are rated on three-point Likert scales indicating how true each behavior is for the child (from 0 = “not true” to 2 = “very true or often true”). The first section of the measure results in three subscale scores (activities, social, school) and a broad summary scale (Total Competence). The second section of the measure results in eight syndrome subscales (anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior) and an “other problems” subscale. Items across these subscales are combined to form a Total Problems score. Additionally, the anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and somatic complaints scales can be combined to create an Internalizing scale, and the rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior scales can be combined to form an Externalizing scale. All subscale and summary scores are converted to T-scores (M = 50, SD = 10). For the Competence scales, lower scores indicate more difficulties and for the Problem scales higher scores indicate more difficulties. Each subscale and summary scale score can be classified as falling into the Clinical, Borderline/At Risk, or Normal Range. In past research, internal consistency across the CBCL scales has ranged from .72 to .94. Test–retest reliability over an 8-day interval for the scales has ranged from .82 to .93.

Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1985)

This standardized self-report measure assesses anxiety for children and adolescents from 6 to 19 years of age. Participants read 37 items that describe how people think or feel and indicate which are true for them. The number of “yes” responses across 28 of these items is tallied and converted to a T-score (M = 50, SD = 10) reported as the Total Anxiety Score. Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety with T-scores equal to or greater than 60 considered outside the Normal Range and those 65 or greater considered in the Clinical Range. In past research, test–retest reliability for the Total Anxiety scale was .68 over a 9-month interval and validity has been demonstrated through high and statistically significant correlations between the Total Anxiety Score and other well-established measures of anxiety. The internal consistency in our sample was .88.

Children’s Depression Inventory-Short Form (CDI-Short Form; Kovacs, 1992)

This ten-item self-report inventory assesses behavioral and cognitive symptoms of depression. For each item, respondents are given three options and asked to pick the one that best described them within the past 2 weeks. The options include absence of the symptom of depression (0), mild or probable symptom of depression (1), or definite symptom of depression (2). Raw scores are converted to T-scores (M = 50; SD = 10) with higher scores indicating increasing severity of depression. T-scores 60 or greater are considered to fall outside the normal range, with those 65 and greater falling into the Clinically Significant range. The alpha reliability coefficient was .80 in the normative sample (Kovacs, 1992) and .78 in our sample.

Children’s Posttraumatic Stress Scale (CPSS; Foa, Johnson, Feeny, & Treadwell, 2001)

This 26-item self-report measure for children aged 8–18 parallels the diagnostic criteria for PTSD included in the DSM-IV. The wording of the instructions was altered to ensure siblings responded related to their experience of their brother or sister’s cancer. Responses indicate the occurrence and overall severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms in the past month with symptom items rated on a 4-point scale (0 = “not at all” to 3 = “5 or more times a week”). A total symptom severity scale is calculated (range = 0–51) with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. Scores greater than or equal to 11 represent moderate to severe posttraumatic stress. For the total symptom severity scale, good internal (alpha = .89) and test–retest reliability over a 1–2 week period (.84) have been reported (Foa et al., 2001). Alpha in our sample was .90.

Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS: Malecki & Demaray, 2002)

The CASSS is a 60-item measure designed to assess multi-faceted social support (i.e., support from parents, teachers, classmates, close friends, and people in the school) for children and adolescents. Respondents are asked to rate the amount of support they receive for each of 12 specific social support items for each source defined above on a six-point Likert scale (1 = never to 6 = always). They also indicate how important they perceive each support action to be on a three-point Likert scale (1 = not very important to 3 = very important). Separate social support (i.e., how often) and importance scores are calculated for each source of support. In past research, internal consistency across the subscales has been good (α = .88–.98) and test–retest reliability over 8–10 weeks suggests moderate to high consistency (rs = .45–.78). Convergent validity has been established by correlating scores on the CASSS with other measures of social support (Malecki & Demaray, 2002). This scale had high internal consistency in our sample ranging from .92 to .96 across sources for amount of support and from .85 to .94 across sources for importance of support.

Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES; DiPerna & Elliott, 2000)

The ACES is a 73-item teacher-completed measure of academic competence. This measure includes two scales: Academic Skills and Academic Enablers. The Academic Skills scale is composed of three subscales: Reading/Language Arts Skills, Mathematics Skills, and Critical Thinking Skills. As evidence of construct validity, Academic Skills scores on the ACES are highly correlated with student performance on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (Hoover, Hieronymous, Frisbie, & Dunbar, 1993). The Academic Enablers scale is composed of four subscales: Interpersonal Skills, Motivation, Engagement, and Study Skills. Evidence for convergent validity has been provided through statistically significant correlations between scores on the Academic Enablers scale and a measure of social skills (DiPerna & Elliott, 1999). Internal consistency for the subscales has ranged from .94 to .99 in past research (DiPerna & Elliott, 2000). The 2- to 3-week test–retest reliability has been reported as .95 for Academic Skills and .96 for Academic Enablers scores.

Statistical Approach

To address the first aim of this paper, a series of Binomial tests (Pett, 1997) were calculated comparing the percentage in our sample falling outside the normal range on the CBCL, RCMAS, and CDI-S to that expected in the general population. The percentage of siblings falling into the moderate to severe range of posttraumatic stress on the CPSS was also calculated. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the mean levels of psychosocial symptomatology for siblings as reported on the CBCL, RCMAS, and CDI.

To address the second aim of the paper, an exploration of perceptions of social support across home and school-based sources, two repeated measures ANOVAs were calculated: one with amount of support as the dependent variable and one with importance of social support as the dependent variable. The independent variable was source of support (parent, teacher, classmate, friend, others in the school) and follow-up tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using a Sidak adjustment. Our sample size provided us with greater than 95% power to detect a small effect (.20) as significant in these analyses at p < .01.

Finally, to determine if adjustment was associated with social support, correlations were calculated between amount of support across the five sources and all of our measures of functioning. Correlations with ps < .01 were considered statistically significant for outcomes reported by parents and siblings to conserve alpha; correlations with ps < .05 were interpreted for outcomes reported by teachers given our restricted sample size. It should be noted that siblings with teacher data did not differ from those without in terms of demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, race, annual household income); however, those with teacher data did report greater support from their teachers (M = 58.06; SD = 11.51) than those without teacher data (M = 53.49; SD = 11.21; t [158] = 2.38, p = .02).

Results

Emotional and Behavioral Functioning

As depicted in Table 1, the percentages of siblings falling into the borderline and clinical ranges on the CBCL tended to be elevated compared to that expected in the normal population. This was evident for the Total Problems, Internalizing, Externalizing, and Total Competence summary scales, and the Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Aggressive Behavior, and Activities subscales. The sibling-report measures suggested that the percentage of siblings falling outside the normal range for anxiety was no different from that expected in the general population and the percentage falling outside the normal range for depression was significantly lower than that expected in the general population. However, over half of our sample (54%) reported moderate to severe cancer-related posttraumatic stress symptoms. As in past studies, despite the tendency to see elevated rates of siblings outside the normal range, mean scores calculated across the siblings in our sample fell within the Normal Range for the CBCL summary scale scores (Total Problem Scale: M = 51.78, SD = 11.23; Internalizing Scale: M = 52.82, SD = 11.14; Externalizing Scale: M = 51.07, SD = 11.16; and Social Competence Scale: M = 46.94, SD = 10.86) as well as for the RCMAS (M = 50.25, SD = 11.29) and the CDI-S (M = 48.12, SD = 8.63).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics on measures of psychosocial adjustment

| Measures | % outside normal range (% in clinical range) |

% expected outside normal range |

Statistical comparison (z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL | |||

| Total problems | 30% (18%) | 16% | 4.66*** |

| Internalizing | 28% (22%) | 16% | 4.23*** |

| Anxious/depressed | 16% (8%) | 8% | 3.88*** |

| Withdrawn/depressed | 13% (5%) | 8% | 2.42* |

| Somatic complaints | 14% (8%) | 8% | 3.01** |

| Externalizing | 23% (15%) | 16% | 2.50* |

| Rule-breaking behavior | 8% (3%) | 8% | .08 |

| Aggressive behavior | 13% (5%) | 8% | 2.71* |

| Other: social problems | 11% (3%) | 8% | 1.25 |

| Other: thought problems | 10% (4%) | 8% | .96 |

| Other: attention problems | 11% (4%) | 8% | 1.54 |

| Total competence | 28% (20%) | 16% | 4.11*** |

| Activities | 15% (8%) | 8% | 3.37*** |

| Social | 7% (2%) | 8% | .17 |

| School | 8% (5%) | 8% | .17 |

| RCMAS: total anxiety | 18% (11%) | 16% | .70 |

| CDI-S: depression | 9% (4%) | 16% | −2.74* |

CBCL child behavior checklist; RCMAS revised children’s manifest anxiety scale; CDI-S children’s depression inventory, short form

p<.02

p<.005

p<.001

Perceptions of Social Support

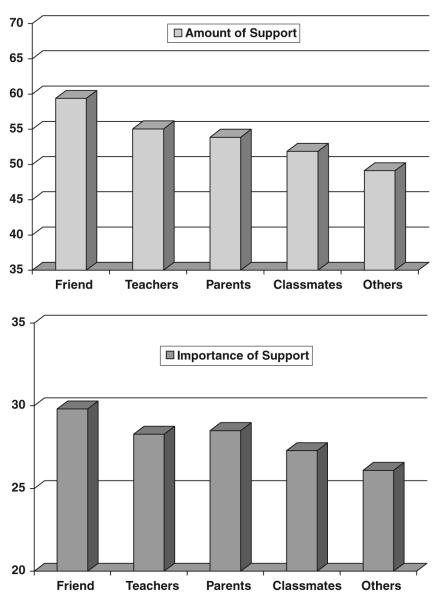

Our primary interest in siblings’ reports of social support concerned the relative amount and importance of support across sources spanning the home (e.g., parents) and school (e.g., teachers, classmates, others). Significant variation was found across support sources for both amount (F [4, 636] = 42.49, p < .001, partial η2 = .21) and importance of support (F [4, 636] = 32.41, p < .001, partial η2 = .17). Figure 1 illustrates the pattern of scores. Support from friends was rated as more plentiful and more important than support from any other source (ps < .001). Support from parents and teachers were rated equally in terms of amount received and importance (ps > .74). Support from parents was rated as more important than support from classmates (p = .005), but these sources provided equal amounts of support (p = .18). The importance of support from teachers and classmates was relatively equal (p = .07), but teachers provided more support (p = .001). Finally, support from others in the school was less important and less available than support from all other sources (ps < .001).

Fig. 1.

Amount of social support (top) and importance of social support (bottom) by source

Associations Between Social Support and Emotional, Behavioral, and Academic Functioning

Table 2 provides correlations between amount of social support from friends, parents, teachers, classmates, and others in the school and our measures of emotional, behavioral, and academic adjustment. Among the sibling self-reported indices of emotional adjustment, parent support was significantly and negatively related to depression scores, but unrelated to anxiety and cancer-related traumatic stress. Of note, support from classmates and others in the school were also significantly and negatively related to sibling self-reports of depression.

Table 2.

Correlations between amount of social support and indices of functioning

| Friend support |

Parent support |

Teacher support |

Classmate support |

Other support |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDI-S: depression (n = 160) | −.12 | −.31*** | −.17 | −.23** | −.28*** |

| RCMAS: anxiety (n = 160) | −.04 | −.15 | −.15 | −.14 | −.18 |

| Posttraumatic stress (n = 160) | .06 | −.12 | −.06 | .03 | −.07 |

| CBCL | |||||

| Total problems (n = 158) | −.16 | −.21* | −.17 | −.20 | −.19 |

| Internalizing (n = 158) | −.16 | −.09 | −.06 | −.12 | −.13 |

| Anxious/depressed (n = 158) | −.08 | .02 | .05 | −.05 | −.03 |

| Withdrawn/depressed (n = 158) | −.36*** | −.32*** | −.20 | −.27*** | −.29*** |

| Somatic complaints (n = 158) | −.01 | .01 | −.02 | .05 | −.07 |

| Externalizing (n = 158) | −.10 | −.22** | −.15 | −.14 | −.11 |

| Rule-breaking behavior (n = 158) | −.26*** | −.33*** | −.24** | −.23** | −.22** |

| Aggressive behavior (n = 158) | −.15 | −.24** | −.18 | −.18 | −.10 |

| Other: social problems (n = 158) | −.14 | −.15 | −.07 | −.15 | −.09 |

| Other: thought problems (n = 158) | −.14 | −.08 | −.06 | −.15 | −.16 |

| Other: attention problems (n = 158) | −.19 | −.28*** | −.24** | −.21** | −.25** |

| Other problems (n = 158) | −.14 | −.25** | −.25** | −.17 | −.18 |

| Total competence (n = 156) | .06 | .24** | .16 | .03 | .15 |

| Activities (n = 156) | .04 | .24** | .11 | −.01 | .12 |

| Social (n = 156) | .12 | .18 | .11 | .05 | .13 |

| School (n = 156) | .13 | .28*** | .25*** | .15 | .19 |

| ACES | |||||

| Academic skills (n = 30) | .32 | .20 | .07 | .22 | .15 |

| Reading (n = 43) | .32+ | .15 | .09 | .14 | .21 |

| Math (n = 34) | .34+ | .28 | .16 | .32 | .19 |

| Critical thinking (n = 39) | .38+ | .20 | .17 | .30 | .21 |

| Academic enablers (n = 50) | .31+ | .31+ | .20 | .18 | .33+ |

| Interpersonal skills (n = 50) | .36* | .36* | .22 | .19 | .37** |

| Engagement (n = 51) | .19 | .22 | .11 | .13 | .23 |

| Motivation (n = 51) | .30+ | .26 | .15 | .13 | .28+ |

| Study skills (n = 51) | .26 | .24 | .20 | .17 | .28+ |

CDI-S children’s depression inventory-short form; RCMAS revised child manifest anxiety scale; CBCL child behavior checklist; ACES academic competence evaluation scales

p<.05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .005

p ≤ .001

In turning to the parent-reported indices of sibling adjustment, parent support was the only form of social support significantly (and negatively) related to Total Problems and the Externalizing summary score on the CBCL. No forms of social support were significantly related to the Internalizing summary score. From among the syndrome subscales on the CBCL, greater support from parents was related to fewer symptoms of Withdrawal/Depression, Rule-breaking Behavior, Aggressive Behavior, Attention Problems, and Other Problems. Except for the Aggressive Behavior syndrome scale, support from school-based sources was also associated with fewer symptoms on each of these syndrome scales. Greater social support from friends, classmates, and others in the school was significantly related to fewer symptoms of Withdrawal/Depression and Rule-breaking Behavior. More support from classmates and others in the school was significantly related to fewer Attention Problems, and greater support from teachers was significantly related to fewer symptoms of Rule-Breaking Behavior, Attention Problems, and Other Problems.

Regarding academic and school-related adjustment, greater levels of parental support were significantly related to Total Competence, Activities, and School performance on the CBCL. Greater levels of teacher social support were also significantly related to better School performance as reported on the CBCL. Because of our lower number of subjects with data from their teachers regarding their behavior in the classroom, significant correlations were more difficult to achieve; however, greater support from parents was related to higher scores on the Academic Enablers scale and the Interpersonal Functioning subscale. On both of these scales, greater support from friends and others in the school were also related to better functioning. More support from friends was related to better Reading Skills, Math Skills, Critical Thinking Skills, and Motivation. More support from others in the school was related to higher Motivation and Study Skills scores.

Discussion

This exploratory study revealed that per parent-reports a substantial number of siblings of children with cancer experience problem behaviors including symptoms of anxiety, depression, withdrawal, somatic complaints, and aggression. Interestingly, as in past studies (e.g., Dolgin et al., 1997; Houtzager et al., 2004), mean levels of emotional distress and problem behaviors did not fall outside the normal range, suggesting that while an important subset of siblings fall into ranges suggestive of maladjustment, many fall into the normal range of functioning and some fall quite low in this range. Reports by the siblings themselves did not indicate that they experienced greater rates of anxiety or depression, but did reveal that over half of our sample experienced moderate to severe cancer-related posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptoms. These rates of moderate to severe PTS are higher than that reported in past research (Alderfer et al., 2003; Packman et al., 1997, 2004a, b) probably reflecting the fact that our sample included siblings of children with cancer who were still on treatment or within 2 years of diagnosis as opposed to long-term survivors. Additionally, a substantial number of siblings scored in the impaired range for social competence, specifically in the area of engaging in activities at a rate similar to their peers. Clearly, siblings of children with cancer experience cancer-related distress and are at risk for adjustment problems as reported in a recent review of the literature (Alderfer et al., 2010).

Within our sample, friends were rated as the most important and greatest source of social support while others in the school were considered the least important and provided the least amount of support. Interestingly, social support from parents and teachers were perceived similarly in terms of both amount and importance. Furthermore, the amount of social support received from classmates was reported to be equal to the amount of support received from parents in our sample, despite the fact that parental support was rated as being more important than classmate support. These patterns strongly suggest that social support from school-based individuals, especially friends, teachers, and classmates is valued and available for school-aged siblings of children with cancer.

Associations between amount of support and indices of emotional, behavioral, and academic adjustment suggest that school-based social support relates to the adjustment of siblings of children with cancer similar to past studies conducted on the general population of children (Demaray & Malecki, 2002a, b; Natvig et al., 2003; Stewart & Sun, 2004). While not associated with as many outcomes as parent support, teacher-based support was found to be associated with better school performance, less rule-breaking, and fewer attention problems. Support from classmates and others in the school were related to fewer symptoms of withdrawal and depression, less rule-breaking, fewer attention problems and greater interpersonal skills, motivation, and social skills in the classroom. Support from friends was also related to less rule-breaking, fewer symptoms of withdrawal and depression, better reading and math skills, and critical thinking skills. These findings suggest that social support from school-based sources, in addition to parents, is related to emotional, behavioral, and academic adjustment of siblings of children with cancer. Interestingly, while the siblings in our sample reported that support from friends is more important to them than support from parents, parental support was related to more indices of adjustment than friend support.

Limitations of Current Research

These findings are not without their limitations. First, it should be noted that while parental-reports of sibling anxiety and depression suggested higher rates of at risk and clinical distress in our sample, self-reports by the siblings did not reveal this same pattern. One could argue that these parents are over-reporting distress in their children. Parents of children with cancer tend to experience elevated levels of distress (e.g., Vrijmoet-Wiersma et al., 2008) and distressed parents have been found to report greater anxiety and depression in their children, compared to child self-report (e.g., Jaser et al., 2005). Alternatively, the siblings themselves may be under-reporting symptoms of anxiety and depression. Qualitative interviews conducted with siblings of children with cancer have revealed that siblings often try to hide their negative emotions (Woodgate, 2006). A third possibility is that the siblings’ themselves attribute their current distress to the cancer experience and therefore report their symptoms on the PTS measure, but not on general measures of anxiety and depression, whereas to the “outsider” or a parent these symptoms of distress may look like general anxiety and depression. Unfortunately, our current data do not allow us to disentangle these various options.

Second, we did not have a comparison group so we cannot determine if the absolute levels of amount and ratings of importance of social support differ for siblings of children with cancer compared to other children. We were surprised to see that parents provided roughly the same amount of support as teachers and classmates; however, from our data we cannot tell if this pattern of findings is unique to siblings of children with cancer. It could be that parental support is lower in our sample due to parents’ need to attend to their sick child. Attempts to compare our findings to past research (e.g., Davidson & Demaray, 2007; Demaray et al., 2005) were hampered due to differences in samples in regard to age range and socioeconomic composition. Furthermore, since we do not have longitudinal data, we cannot determine if patterns in amount of social support have changed for the students in our sample in response to their brother or sister being diagnosed with cancer. These are important questions that may help guide future intervention or prevention programs to help support siblings of children with cancer.

Third, the cross-sectional nature of our data does not allow us to assert that greater levels of social support have led to better outcomes for these children. Our findings, however, are largely consistent with past cross-sectional and longitudinal research conducted on broad samples of children (e.g., Demaray et al., 2005), thus future research may confirm a longitudinal relationship between social support and better functioning for siblings of children with cancer. Lastly, we did not present variation in our findings as a function of age or gender, despite our broad age range.

Conclusions

The family is the primary social support system for children and adolescents (e.g., Newman et al., 2007); however, childhood cancer disrupts family patterns and may interfere substantially with the family-based support that healthy siblings typically receive. Parents of children with cancer report difficulty in attending to the needs of both their sick and healthy children (Enskar, Carlsson, Golsater, Hamrin, & Kreuger, 1997; McGrath, 2001; Rocha-Garcia et al., 2003; Sidhu, Passmore, & Baker, 2005). Based upon the findings of this study suggesting that school-based support is important and potentially protective for siblings of children with cancer, we propose that family–school partnerships may be particularly useful in supporting siblings of children with cancer.

The family and members from the medical community can team together with school personnel to create an environment at the school that is welcoming and reassuring for the siblings of children with cancer. School personnel who are appropriately educated about cancer may dispel others’ misconceptions and effectively answer any medical questions that arise in the school, be they from the sibling or a classmate. Providing education to the class about cancer and the specific diagnosis of the child may help the sibling to better understand the disease and spare him or her from needing to answer the questions of classmates. Information about the stressful nature of cancer diagnosis and treatment and possible psychosocial reactions of family members, siblings, friends, and others who know the family may be particularly important. Providing school personnel with this information will cue them to attend to the level of adjustment of the sibling and others in the school. Additionally, within these educational sessions, a skills-based approach can be taken to teach school personnel and classmates ways to be supportive toward the sibling and sensitive to his or her specific needs. Lastly, providing the sibling with individual services or support in the school, from a school counselor, teacher, coach, principal, or trained peer may also be a valuable component of such partnerships. Through such a partnership, the school can begin to reduce the burden of cancer for the family and siblings of children with cancer. This type of partnership may help bolster the school-based social support for siblings and provide them with a safe and reliable outlet outside of the family to express their needs, talk about their experiences, and have their feelings validated. Future research should aim to develop and pilot test such programs in partnership with families and school personnel.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [CA11092 to M.A.A.] and the American Cancer Society [MRSG05213 to M.A.A.]. We thank these sponsors and Lynne Kaplan, Ph.D., K. Julia Kaal, M.A., Caroline Stanley, Ph.D., Rowena Conroy, Ph.D., and the SIBS-C and ACS Friendship Study research teams for their contributions to the research presented here. We also thank the families who so generously participated in the project.

Contributor Information

Melissa A. Alderfer, The Cancer Center at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Department of Pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Room 1485 CHOP North, 34th & Civic Center Blvd., Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

Jilda A. Hodges, Department of School Psychology, Lehigh University College of Education, Bethlehem, PA, USA

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer MA, Kazak AE. Family issues when a child is on treatment for cancer. In: Brown RT, editor. Comprehensive handbook of childhood cancer and sickle cell disease: A biopsychosocial approach. Oxford; New York: 2006. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer MA, Labay LE, Kazak AE. Brief report: Does posttraumatic stress apply to siblings of childhood cancer survivors? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28:281–286. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer MA, Long K, Lown EA, Marsland A, Ostrowski N, Hock J, Ewing L. Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-oncology. 2010 doi: 10.1002/pon.1638. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Chung JYY, Greenberg M, Fleming C. Preliminary investigation of a group intervention for siblings of pediatric cancer patients. Children’s Health Care. 2002;31:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Fleming CF, Khan FS. The role of emotional social support in the psychological adjustment of siblings of children with cancer. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2004;30:103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2003.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter PJ, Sahler OJZ. Sibling perception and adaptation to childhood cancer: Conceptual and methodological consideration. In: Johnson JH, Johnson SB, editors. Advances in child health psychology. University of Florida Press; Gainesville, FL: 1991. pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DS, Friedrich WN, Jaworski TM, Copeland D, Pendergrass T. Pediatric cancer: Predicting sibling adjustment. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1994;50:303–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LM, Demaray MK. Social support as a moderator between victimization and internalizing-externalizing distress from bullying. School Psychology Review. 2007;36:383–405. [Google Scholar]

- Demaray MK, Malecki CK. Critical levels of perceived social support associated with student adjustment. School Psychology Quarterly. 2002a;17:213–241. [Google Scholar]

- Demaray MK, Malecki CK. The relationship between perceived social support and maladjustment for students at risk. Psychology in the Schools. 2002b;39:305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Demaray MK, Malecki CK, Davidson LM, Hodgson KK, Rebus PJ. The relationship between social support and student adjustment: A longitudinal analysis. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42:691–706. [Google Scholar]

- DiPerna JC, Elliott SN. Development and validation of the Academic Competence Evaluation Scales. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1999;17:207–225. [Google Scholar]

- DiPerna JC, Elliott SN. ACES academic competence evaluation scales: Manual K-12. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dolgin MJ, Blumensohn R, Mulhern RK, Orbach J, Sahler OJ, Roghmann KJ, et al. Sibling adaptation to childhood cancer collaborative study: Cross-cultural aspects. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1997;15:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Felner RD, Meares H, Krier M. Prospective investigation of the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage, life stress, and social support on early adolescent adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:511–522. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Tisak J, Causey D, Hryshko A, Reid G. A two-year longitudinal study of stressful life events, social support, and social problem solving skills. Child Development. 1991;62:583–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enskar K, Carlsson M, Golsater M, Hamrin E, Kreuger A. Parental reports of changes and challenges that result from parenting a child with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 1997;14:156–163. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4542(97)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Johnson K, Feeny N, Treadwell K. The Child PTSD Symptom Scale: A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:376–384. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover HD, Hieronymous AN, Frisbie DA, Dunbar SB. Iowa test of basic skills. Riverside; Chicago: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Houtzager BA, Grootenhuis MA, Caron HN, Last BF. Quality of life and psychological adaptation in siblings of paediatric cancer patients, 2 years after diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:499–511. doi: 10.1002/pon.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Y, Frick PJ. Negative life events and the adjustment of school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:370–380. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2704_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, Langrock AM, Keller G, Merchant MJ, Benson M, Reeslund K. Coping with the stress of parental depression II: Adolescent and parent reports of coping and adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:193–205. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostelecky KL, Lempers JD. Stress, family social support, distress and well-being in high school seniors. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal. 1998;27:125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s depression inventory (CDI): Technical manual update. Multi-Health Systems; North Tonawanda, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Malecki CK, Demaray MK. Measuring perceived social support: Development of the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale. Psychology in the Schools. 2002;39:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath P. Findings of the impact of treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia on family relationships. Child and Family Social Work. 2001;6:229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Natvig GK, Albrektsen G, Qvarnstrom U. Associations between psychosocial factors and happiness among school adolescents. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2003;9:166–175. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172x.2003.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman BM, Newman PR, Griffen S, O’Connor K, Spas J. The relationship of social support to depressive symptoms during the transition to high school. Adolescence. 2007;42:441–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolbris M, Enskar K, Hellstrom A. Experience of siblings of children treated for cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2007;22:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packman WL, Crittenden MR, Schaeffer E, Bongar B, Fischer JBR, Cowan MJ. Psychosocial consequences of bone marrow transplantation in donor and nondonor siblings. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1997;18:244–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packman WL, Fine J, Chesterman B, Van Zutphen K, Golan R, Amylon M. Camp Okizu: Preliminary investigation of a psychological intervention for siblings of pediatric cancer patients. Children’s Health Care. 2004a;33:201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Packman WL, Gong K, vanZutphen K, Shaffer T, Crittenden M. Psychosocial adjustment of adolescent siblings of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2004b;21:233–248. doi: 10.1177/1043454203262698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM, Holm KE, Gurney JG. The impact of childhood cancer on the family: A qualitative analysis of strains, resources, and coping behaviors. Psycho-oncology. 2004;13:390–407. doi: 10.1002/pon.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pett MA. Nonparametric statistics for healthcare research: Statistics for small samples and unusual distributions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Printz BL, Shermis MD, Webb PM. Stress-buffering factors relations to adolescent coping: A path analysis. Adolescence. 1999;34:715–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond B. Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) Manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, et al., editors. [Retrieved August 1, 2008];SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2005. 2008 from http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/

- Rocha-Garcia A, Del Río A. Alvarez, Hérnandez-Peña P, Martinez-Garcia Mdel C, Marin-Palomares T, Lazcano-Ponce E. The emotional response of families to children with leukemia at the lower socio-economic level in central Mexico. Psycho-oncology. 2003;12:78–90. doi: 10.1002/pon.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahler OJ, Roghmann K, Carpenter P, Mulhern RK, Dolgin MJ, Sargent JR, et al. Sibling adaptation to childhood cancer collaborative study: Prevalence of sibling distress and definition of adaptation levels. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1994;15:353–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu R, Passmore A, Baker D. An investigation into parent perceptions of the needs of siblings of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2005;22:276–287. doi: 10.1177/1043454205278480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloper P, While D. Risk factors in the adjustment of siblings of children with cancer. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1996;37:597–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D, Sun J. How can we build resilience in primary school aged children? The importance of social support from adults and peers in family, school and community settings. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2004;16:S37–S41. doi: 10.1177/101053950401600s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torsheim T, Aaroe LE, Wold B. School-related stress, social support, and distress: Prospective analysis of reciprocal and multilevel relationships. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2003;44:153–159. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijmoet-Wiersma C, van Klink J, Kolk A, et al. Assessment of parental psychological stress in pediatric cancer: A review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:694–706. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel DJ, Devereux P, Leigh GK, Ballard-Reisch D. A longitudinal study of adolescents’ perceptions of support and stress. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1998;13:158–177. [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL. Siblings’ experiences with childhood cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29:406–414. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200609000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ystgeerd M. Life stress, social support and psychological distress in late adolescence. Social Psychiatry and Epidemiology. 1997;32:277–283. doi: 10.1007/BF00789040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]