Abstract

Although cancer vaccines are emerging as innovative methods for cancer treatment, these alone have limited potential for treating measurable tumor burden. Thus, the importance of identifying anticancer strategies with greater potency is necessary. The chimeric DNA vaccine CTGF/E7 (connective tissue growth factor linked to the tumor antigen human papillomavirus 16 E7) generates potent E7-specific immunity and antitumor effects. We tested immune-modulating doses of chemotherapy in combination with the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine to treat existing tumors in mice. Metronomic low doses of paclitaxel, not the maximal tolerable dose, are synergistic with the antigen-specific DNA vaccine. Paclitaxel, given in metronomic sequence with the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine enhanced the vaccine's potential to delay tumor growth and decreased metastatic tumors in vivo better than the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine alone. The two possible mechanisms of metronomic paclitaxel chemotherapy are the depletion of regulatory T cells and the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis rather than direct cancer cell cytolytic effects. Results indicate that combination treatment of metronomic chemotherapy and antigen-specific DNA vaccine can induce more potent antigen-specific immune responses and antitumor effects. This provides an immunologic basis for further testing in cancer patients.

Introduction

Conventional modalities for cancer treatment are surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. The metastatic nature of cancer requires that the effect of any treatment be distributed throughout the body. Although chemotherapy is used systemically to destroy any residual or metastatic tumor cells, it cannot discriminate between neoplastic and non-neoplastic cells. Immunotherapy has recently provided an attractive alternative approach, purposely antigen-specific, with its potential ability to eradicate systemic cancer lesions and differentiate between normal and cancer cells.1

Chemotherapeutic agents suppress host immunity by causing the apoptosis of immunocytes. However, these agents also modulate the immune response to improve antitumor effects.2,3 Kerbel et al.4 recently developed a new strategy for cancer therapy using the concept of metronomic (low-dose) chemotherapy instead of the current maximum tolerated dose (MTD) chemotherapy. Their results reveal that the possible mechanism of metronomic chemotherapy is antiangiogenesis.

Paclitaxel is a very effective agent for treating many malignancies, including breast and ovarian carcinomas, lung cancer, head and neck tumors, melanomas, gastric carcinomas, and cervical cancer.5,6 It promotes the assembly of microtubules, inhibits tubulin disassembly7 and DNA synthesis,8 and releases tumor necrosis factor-α9 to cause apoptosis in a variety of cancer cell types.10 Not withstanding MTD chemotherapy, microtubule-interfering agents such as paclitaxel were the first chemotherapeutic agents to have antiangiogenic activity by acting primarily on endothelial cells.11 Paclitaxel, at 3 or 6 mg/kg daily, is effective in inhibiting intratumor angiogenesis in a mouse model.12

Vaccination as a form of specific immunotherapy for cancer has been investigated for years. Tumors that express specific antigens, such as breast and cervical cancer, are considered suitable candidates for immunotherapy.13,14 Encouraging in vitro and animal studies have led to several clinical trials for malignant disorders.15,16 DNA or gene vaccines directed against human papillomavirus E7 tumor antigen protects mice from challenge with E7-expressing tumor cells and pulmonary metastatic tumors.17,18,19

We investigated the potential benefits of combined chemotherapy and antigen-specific immunotherapy to improve cancer management. Immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy was tested to determine whether it could augment the efficacy of either agent in a rapidly growing, lethal murine cervical tumor model. We also investigated possible mechanisms for the effects of combined immunotherapy and chemotherapy.

Results

CTGF/E7 chimeric DNA vaccine with metronomic paclitaxel enhanced survival

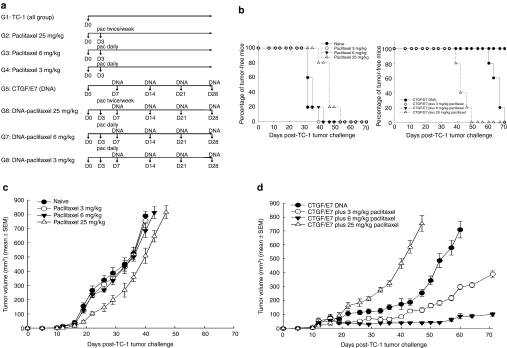

Tumor-bearing mice that received chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy were first tested for possible therapeutic benefits. The survival curves of mice that received connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)/E7 DNA vaccine only, CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with various doses of paclitaxel, or paclitaxel only are shown in Figure 1b. None of the mice survived after 55 days of tumor challenge, regardless of the amount of paclitaxel received. All of the mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine plus 3 or 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel were alive after 70 days of tumor challenge. They also had significantly longer survival durations compared to the other groups (P < 0.05, Kaplan–Meier test). Mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine only had longer survival than those that received paclitaxel only (P < 0.05, Kaplan–Meier test). However, the survival curve of mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine plus 25 mg/kg paclitaxel was not longer than those of mice that received 25 mg/kg paclitaxel only (P > 0.05) and was even shorter than those that received CTGF/E7 DNA only (P < 0.05, Kaplan–Meier test). Mice given CTGF/E7 chimeric DNA vaccine in combination with metronomic paclitaxel survived the longest.

Figure 1.

In vivo tumor treatment experiments. (a) Diagrammatic representation of the different treatment regimens of paclitaxel and/or DNA vaccination. (b) Overall survival of mice treated with various doses of paclitaxel only or with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination. The mice were first inoculated with TC-1 tumor cells and treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine only, CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine combined with various doses of paclitaxel, or paclitaxel only as described in Materials and Methods section. All of the mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine in combination with 3 or 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel were alive even after 70 days of tumor challenge and had significantly longer survival durations compared to the other groups. The survival curve of mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine plus 25 mg/kg paclitaxel was not longer than those of mice that received 25 mg/kg paclitaxel only (P > 0.05) and was even shorter than those vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA only (P < 0.05, Kaplan–Meier test). (c) Tumor volumes of mice treated with various doses of paclitaxel only. The mice were first inoculated with TC-1 tumor cells and treated with respective doses of paclitaxel, and the tumor sizes were calculated as described in Materials and Methods section. Mice treated with 25 mg/kg paclitaxel had smaller tumor volumes than the naive group and the 3 or 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel-treated mice (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (d) Tumor volumes of mice treated with various doses of paclitaxel and CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination. The mice were first inoculated with TC-1 tumor cells and then treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination only or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination with respective doses of paclitaxel and the tumor sizes were calculated as described in Materials and Methods section. Mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine combined with 3 or 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel had significantly smaller tumor volumes than those treated with CTGF/E7 DNA only, or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine combined with 25 mg/kg of paclitaxel. Pooled data of three experiments (five mice per group) were calculated. Each result represents experiments in triplicate. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor.

Antitumor effects of CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine combined with metronomic chemotherapy

Chemotherapeutic effects, measured as tumor volume, in mice with TC-1 subcutaneous tumors, were compared. Mice treated with 25 mg/kg paclitaxel (507.8 ± 31.2 mm3 on day 40) had the smallest tumor volume compared to other paclitaxel-treated groups [naive group (751.8 ± 46.5 mm3 on day 40), 3 mg/kg paclitaxel (755.6 ± 49.2 mm3 on day 40), and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel (685.0 ± 49.2 mm3 on day 40)] [P < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)] (Figure 1c).

Combined therapy with antigen-specific DNA vaccine and cytotoxic chemotherapy was further evaluated to determine whether it could generate a more potent in vivo antitumor effect than either therapy alone. Mice that received CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 25 mg/kg paclitaxel (753.3 ± 56.6 mm3 on day 47) and those that received 25 mg/kg paclitaxel only (774.9 ± 67.2 mm3 on day 47) had similar tumor volumes (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 1d). On the other hand, mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine only (255.8 ± 25.1 mm3 on day 47) had smaller tumor volumes than those that received the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 25 mg/kg paclitaxel (753.3 ± 56.6 mm3 on day 47) (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Moreover, mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 3 mg/kg (132.4 ± 18.8 mm3 on day 47) or 6 mg/kg (40.4 ± 6.8 mm3 on day 47) of paclitaxel had significantly smaller tumor volumes than those treated with CTGF/E7 DNA only (255.8 ± 25.1 mm3 on day 47) (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA). Mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel even had significantly smaller tumor volumes than those treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 3 mg/kg of paclitaxel (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Thus, CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination combined with metronomic chemotherapy produced the most potent antitumor effect.

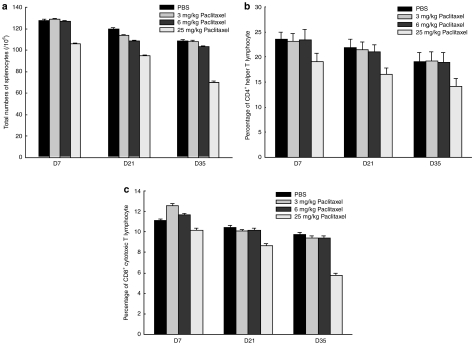

In vivo effect of paclitaxel dose and duration

The influence of paclitaxel on the quantity of immunocytes was evaluated. Total splenocytes (per 106 cells) of mice in the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) group (128.0 ± 2.0 × 106 on day 7, 120.0 ± 1.2 × 106 on day 21, 109.0 ± 1.0 × 106 on day 35), 3 mg/kg paclitaxel group (129.0 ± 1.0 × 106 on day 7, 114.0 ± 1.0 × 106 on day 21, 108.0 ± 1.2 × 106 on day 35), and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel group (127.0 ± 0.7 × 106 on day 7, 109.0 ± 0.9 × 106 on day 21, 104.0 ± 1.1 × 106 on day 35) were significantly higher than those of mice injected with 25 mg/kg of paclitaxel (106.0 ± 1.0 × 106 on day 7, 95.0 ± 0.8 × 106 on day 21, 70.0 ± 1.0 × 106 on day 35) after 7 days of drug administration (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Kinetic changes of various subtypes of lymphocytes. (a) Total numbers of splenocytes in mice treated with various doses of paclitaxel. Mice first received various doses of paclitaxel and their splenocytes were harvested and counted as described in the Materials and Methods section. Total splenocytes of mice treated with 25 mg/kg paclitaxel were significantly lower than those of the other groups treated with PBS or lower doses of paclitaxel after 7 days of drug administration. (b) Bar figures show percentages of CD4+ helper T lymphocytes from total splenocytes. Percentages of CD4+ helper T lymphocytes in 25 mg/kg paclitaxel group were lower than the other groups after 7 days of drug administration. (c) Bar figures show percentages of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes from total splenocytes. The percentages of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes decreased significantly in the 25 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated group compared to other groups after 21 days of drug administration.

The percentages of CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the splenocytes of different groups were further evaluated. Percentages of CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes decreased significantly in the 25 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated group as compared to the other groups (day 7, 23.5 ± 1.4% in the PBS group, 23.1 ± 1.6% in the 3 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 23.4 ± 2.1% in the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 19.0 ± 1.3% in the 25 mg/kg paclitaxel group; day 21, 21.9 ± 1.6% in the PBS group, 21.4 ± 1.6% in the 3 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 21.0 ± 1.4% in the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 16.5 ± 1.3% in the 25 mg/kg paclitaxel group; day 35, 19.1 ± 1.8% in the PBS group, 19.2 ± 1.8% in the 3 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 18.9 ± 1.9% in the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 14.2 ± 1.8% in the 25 mg/kg paclitaxel group) (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) after 7 days of drug administration (Figure 2b). There was no difference among the PBS, 3 mg/kg paclitaxel, and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated groups (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

For CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the splenocytes, similar to those of CD4+ helper T lymphocytes, the percentages of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes decreased significantly in the 25 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated group compared to other groups after 21 days of drug administration (day 21, 10.5 ± 0.2% in the PBS group, 10.1 ± 0.2% in the 3 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 10.4 ± 0.3% in 6 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 8.7 ± 0.2% in the 25 mg/kg paclitaxel group, day 35, 9.7 ± 0.2% in the PBS group, 9.4 ± 0.20% in the 3 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 9.4 ± 0.2% in the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 5.8 ± 0.3% in the 25 mg/kg paclitaxel group) (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 2c). There was no difference among the PBS, 3 mg/kg paclitaxel, and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated groups (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). In vivo, paclitaxel decreased the total quantity of immunocytes in a dose and duration dependent manner.

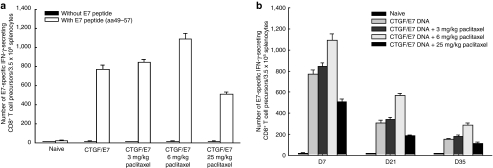

Effect of metronomic chemotherapy on antigen-specific immunity

Antigen-specific immune responses of mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine, after receiving different doses of paclitaxel, were first evaluated 7 days after the last immunization. The frequencies of interferon-γ-secreting CD8+ T precursors were highest in mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel (1,092.5 ± 61.5) compared to the other groups (for the CTGF/E7 DNA group, 767.0 ± 45.5; for the CTGF/E7 plus 3 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 842.0 ± 33.0; for the CTGF/E7 plus 25 mg/kg paclitaxel group, 508.0 ± 28.0, P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

E7-specific immunity in mice that received various doses of paclitaxel and CTGF/E7 chimeric DNA vaccine. The mice were first immunized with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine only or in combination with various doses of paclitaxel. The mice were then killed and their splenocytes were collected and stained with anti-CD8 and anti-IFN-γ antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the Materials and Methods section. (a) Bar figures show the frequencies of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell precursors 7 days after the last immunization. The frequencies of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T precursors in the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated group were significantly higher than those in the other groups that received the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 3 or 25 mg/kg paclitaxel (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). (b) Bar figures show kinetic changes in frequencies of E7-sepcific CD8+ T precursors among splenocytes. The numbers of E7-specific CD8+ T precursors in mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel were higher than in mice that received the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine only, regardless of the time interval. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor.

We also evaluated whether chemotherapy could generate higher and more persistent antigen-specific T-cell immunity when combined with the naked DNA vaccine. The numbers of E7-specific CD8+ T precursors in mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel were highest among the groups from 7 to 35 days after last immunization (day 21 PBS, 308.0 ± 23.0; 3 mg/kg paclitaxel, 342.0 ± 18.0; 6 mg/kg paclitaxel, 568.5 ± 23.5; 25 mg/kg paclitaxel, 184.5 ± 10.5; day 35 PBS, 150.5 ± 14.8; 3 mg/kg paclitaxel, 177.5 ± 12.5; 6 mg/kg paclitaxel, 288.0 ± 20.0; 25 mg/kg paclitaxel, 112.5 ± 9.5, P < 0.01 one-way ANOVA) (Figure 3b). Mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel had the highest numbers of E7-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes compared to the other groups at 7, 21, and 35 days after last immunization (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA). Metronomic chemotherapy enhanced antigen-specific immunity.

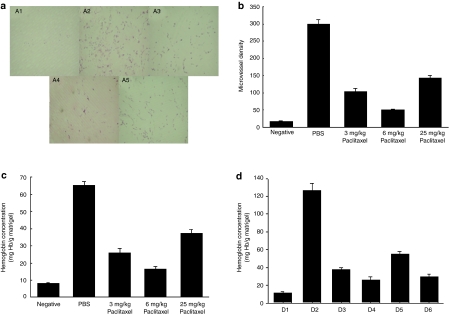

Effect of metronomic paclitaxel on in vivo angiogenesis

We evaluated whether chemotherapy inhibited in vivo tumor growth via an antiangiogenic pathway. The representative figures of matrigel assays in each group of C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice are shown in Figure 4a. The microvessel of matrigel implants in paclitaxel-treated mice (87.0 ± 10.0 in the 3 mg/kg group, 67.0 ± 7.0 in the 6 mg/kg group, and 154.0 ± 12.0 in the 25 mg/kg group) were significantly lower than those in the PBS-treated C57BL/6 mice (265.5 ± 14.5 mg hemoglobin (Hb)/g matrigel) (P < 0.01, ANOVA) (Figure 4b). However, the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated mice had the lowest microvessel density (MVD) among the three paclitaxel-treated groups (P < 0.01, ANOVA) (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

In vivo angiogenesis assay characterizing antiangiogenic effects of various doses of paclitaxel. Matrigel was mixed with heparin and basic fibroblast growth factor, and was injected subcutaneously into the abdominal midline of C57BL/6 or BALB/c nude mice (a total 0.5 mg/mouse) on day 0. The mice were given 25 mg/kg of paclitaxel on days 0, 3, and 7, or 3 mg/kg or 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel every day intraperitoneally from days 0 to 10 and/or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine on days 0 and 7. They were killed on day 11. The matrigel plugs were retrieved, resected, fixed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to determine microvessel density (MVD). The remaining half of the matrigel plugs were assayed for hemoglobin content as described in the Materials and Methods section. (a) Representative matrigel plugs: A1, negative; A2, PBS only; A3, 3 mg/kg paclitaxel; A4, 6 mg/kg paclitaxel; and A5, 25 mg/kg paclitaxel. (b) Bar graph shows the MVDs of matrigel plugs in C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice treated with various doses of paclitaxel. The MVDs of matrigel implants in 6-mg/kg paclitaxel-treated mice were significantly lower than those in the other paclitaxel and PBS-treated mice. (c) Bar graph shows matrigel hemoglobin content for C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice treated with various doses of paclitaxel. The hemoglobin concentrations of matrigel implants in 6-mg/kg paclitaxel-treated mice were lowest among the paclitaxel-treated groups. (d) Bar graph shows matrigel hemoglobin content for BALB/c immunocompromised nude mice treated with various doses of paclitaxel: D1, negative; D2, PBS only; D3, 3 mg/kg paclitaxel only; D4, 6 mg/kg paclitaxel only; D5, 25 mg/kg paclitaxel only; and D6, 6 mg/kg paclitaxel and CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine. The hemoglobin contents of matrigel implants in the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated (D4 and D6) groups were significantly lower than those in the other (D2, D3, and D5) groups in BALB/c nude mice. CTGF, connective tissue growth factor.

Moreover, the Hb contents of matrigel implants in paclitaxel-treated C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice (mg Hb/g matrigel), (25.8 ± 2.6 in the 3 mg/kg group, 16.2 ± 1.9 in the 6 mg/kg group, and 37.0 ± 2.3 in the 25 mg/kg group) were also significantly lower than those in PBS-treated mice (65.0 ± 2.5 mg Hb/g matrigel) (P < 0.01, ANOVA) (Figure 4c). However, Hb concentrations were lowest in the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated mice than those in the 3 or 25 mg/kg paclitaxel groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

The influence of T lymphocytes on the antiangiogenic effect of paclitaxel was evaluated. Matrigel assays were performed in BALB/c nu/nu immunocompromised mice as described in the Materials and Methods section. The paclitaxel-treated groups had lower Hb concentrations than the positive group (Figure 4d). However, 6 mg/kg paclitaxel only (26.2 ± 3.3 mg Hb/g matrigel) or 6 mg/kg paclitaxel with the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine (29.6 ± 2.6 mg Hb/g matrigel) had similarly lower Hb concentrations compared to 3 mg/kg paclitaxel only (37.5 ± 2.5 mg Hb/g matrigel) and 25 mg/kg paclitaxel only (54.9 ± 2.8 mg Hb/g matrigel) groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

The results indicated that the metronomic chemotherapy inhibited in vivo angiogenesis in both C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice and BALB/c nu/nu immunocompromised mice.

Effect of metronomic paclitaxel increased CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in local tumor environment

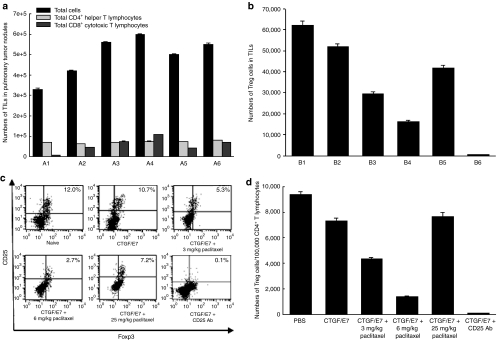

We evaluated whether metronomic chemotherapy influenced immunity in the local tumor environment. C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were inoculated with 5 × 104/mouse TC-1 tumor cells intravenously via the tail vein and treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination only, various doses of paclitaxel, or CD25 antibody (Ab) as described earlier. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from lung tissues and splenocytes were harvested on day 28 after tumor challenge to evaluate the influence of the cytotoxic drug on subtypes of T lymphocytes in tumor-bearing mice. The total numbers of TILs in the 3 and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated and CD25 Ab depleted groups were higher than those in the other groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 5a). The numbers of CD4+ helper T cells among the TILs were similar in vaccinated groups (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). However, the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated group had the highest numbers of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells among the TILs compared to the other groups (Figure 5a). Metronomic paclitaxel increased CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the local tumor environment.

Figure 5.

Lymphocyte subtypes from tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and splenocytes. (a) Bar figures show total TILs, CD4+ helper, and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells from TILs. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with TC-1 tumor cells intravenously via the tail vein and treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination only, vaccination combined with various doses of paclitaxel, or CD25 antibody, and the TILs from lung tissues were harvested on day 28 after tumor challenge as described in the Materials and Methods section. A1, naive; A2, CTGF/E7 DNA only; A3, CTGF/E7 DNA plus 3 mg/kg paclitaxel; A4, CTGF/E7 DNA plus 6 mg/kg paclitaxel; A5, CTGF/E7 DNA plus 25 mg/kg paclitaxel; A6, CTGF/E7 DNA plus CD25 antibody. The total numbers of TILs in the 3 and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated and CD25 antibody depletion groups were greater than those in the other groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). However, the 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated group had the highest numbers of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells from the TILs compared to the other groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (b) Bar figures show total Treg cells among TILs. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with TC-1 tumor cells, treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination only, vaccination combined with various doses of paclitaxel, or CD25 antibody, and their TILs were harvested for further analysis on calculation of CD8+ cytotoxic cell/Treg cell ratio from TILs. The ratio of cytotoxic and regulatory T cells was evaluated to determine if it reflected antitumor effects. C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were inoculated with TC-1 tumor cells intravenously and treated with various doses of paclitaxel and/or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine, and TILs from lung tissues were harvested as described earlier. The TILs were stained with various antibodies and the numbers of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD3+CD8+) and Treg cells (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) were analyzed and counted by flow cytometry in each group as described earlier. The ratio of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and Treg cells among the TILs from each group was calculated. Day 28 after tumor challenge as described in Materials and Methods section. B1, naive; B2, CTGF/E7 DNA only; B3, CTGF/E7 DNA plus 3 mg/kg paclitaxel; B4, CTGF/E7 DNA plus 6 mg/kg paclitaxel; B5, CTGF/E7 DNA plus 25 mg/kg paclitaxel; B6, CTGF/E7 DNA plus CD25 antibody. Mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination and paclitaxel or CD25 antibody had significantly lower percentages of Treg cells/CD4+ helper T cells in TILs than those treated with CTGF/E7 DNA only (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). The 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated group also had the lowest percentage of Treg cells/CD4+ helper T cells among the paclitaxel-treated groups. (c) Representative figures show flow cytometry analyses of Treg cells from splenocytes. (d) Bar figures show percentages of Treg cells among CD4+ T cells from splenocytes. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with TC-1 tumor cells, treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination only, vaccination combined with various doses of paclitaxel, or CD25 antibody, and their splenocytes were harvested for further analysis on day 28 after tumor challenge as described in Materials and Methods section. CTGF/E7 DNA vaccinated mice treated with 3 or 6 mg/kg paclitaxel, or CD25 antibody had significantly lower numbers of Treg cells from splenocytes compared to the other groups. Mice treated with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel had the lowest numbers of Treg cells from splenocytes among the three paclitaxel-treated groups. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; Treg, T regulatory.

For the evaluation of T regulatory (Treg) cells among the TILs, the percentages of Treg cells/CD4+ helper T cells were used to represent the status of Treg cells among the TILs. Mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine and various doses of paclitaxel or CD25 Ab had significantly lower percentages of Treg cells/CD4+ helper T cells than those treated with CTGF/E7 DNA only or the naive group (P < 0.05 one-way ANOVA) (Figure 5b). The 6 mg/kg paclitaxel-treated group also had the lowest percentages of Treg cells/CD4+ helper T cells among the paclitaxel-treated groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Treg cells among splenocytes in various vaccinated groups were evaluated. Representative figures of flow cytometric analyses of Treg cells among splenocytes are shown in Figure 5c. CTGF/E7 DNA vaccinated mice treated with 3 or 6 mg/kg paclitaxel, or CD25 antibody had significantly lower numbers of Treg cells among splenocytes compared to the other groups (PBS, 9,350 ± 232; CTGF/E7, 7,310 ± 245; CTGF/E7 plus 3 mg/kg paclitaxel, 4,370 ± 86; CTGF/E7 plus 6 mg/kg paclitaxel, 1,360 ± 88; CTGF/E7 plus 25 mg/kg paclitaxel, 7,360 ± 351; CTGF/E7 plus CD25 Ab, 80 ± 16, P < 0.01 one-way ANOVA) (Figure 5d). Mice treated with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel had the lowest numbers of Treg cells in the splenocytes among the three paclitaxel-treated groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Essential cells for the antitumor effect of CTGF/E7 DNA combined with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel

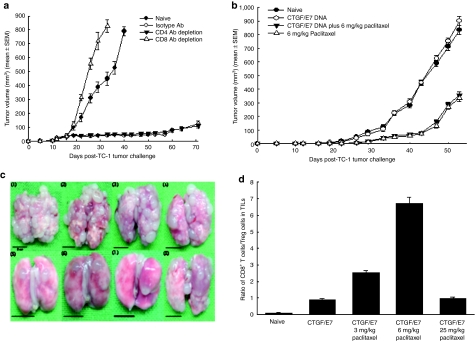

To determine the subset of lymphocytes important for the antitumor effect of chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy, in vivo Ab depletion experiments were performed. C57BL/6 mice that received the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine combined with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel depleted of CD4+ T cells had similar smaller tumor sizes compared to those without antibody depletion (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). The tumor sizes of mice that received the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine combined with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel depleted of CD8+ T cells grew larger than those even in naive C57BL/6 mice (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 6a). Only CD8+ T cells were essential for the antitumor effect of by CTGF/E7 DNA combined with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel.

Figure 6.

In vivo antibody depletion experiments, in vivo pulmonary metastatic tumor experiments, and ratios of host antitumor and regulatory immunities. (a) In vivo antibody depletion experiments were conducted using a subcutaneous tumor model in C57BL/6 mice. C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were subcutaneously challenged with TC-1 tumor cells and treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination in combination with 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel, and CD4 or CD8 antibody depletion was started on the day of TC-1 tumor challenge as described in the Materials and Methods section. The tumor sizes of mice that received CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination combined with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel and depleted of CD8+ T cells grew larger than those even in naive C57BL/6 mice. (b) In vivo experiments using the subcutaneous tumor model in BALB/c nude mice. BALB/c nude mice (five per group) were subcutaneously challenged with TC-1 tumor cells and treated with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination combined with 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel, and CD4 or CD8 antibody depletion was started on the day of TC-1 tumor challenge as described earlier. BALB/c nude mice that received 6 mg/kg paclitaxel only or in combination with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination had similar smaller tumors than those of naive or those that received only CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination. (c) Representative figures show pulmonary tumor nodules in C57BL/6 mice: C1, naive; C2, 3 mg/kg paclitaxel; C3, 6 mg/kg paclitaxel; C4, 25 mg/kg paclitaxel; C5, CTGF/E7 DNA; C6, CTGF/E7 DNA and 3 mg/kg paclitaxel; C7, CTGF/E7 DNA and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel; and C8, CTGF/E7 DNA and 25 mg/kg paclitaxel. C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were intravenously challenged with 5 × l04 TC-1 tumor cells/mouse via the tail vein, and paclitaxel and/or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination were given, and the mice were killed 28 days after tumor challenge in Materials and Methods section to evaluate whether the DNA vaccine combined with chemotherapy also controlled metastatic tumors better than the DNA vaccine only. C57BL/6 mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel had the fewest pulmonary tumor nodules compared to those treated with CTGF/E7 DNA only, vaccination plus 3 or 25 mg/kg of paclitaxel. (d) Ratios of CD8+ T cells/Treg cells from TILs in various groups. C57BL/6 mice were intravenously inoculated with TC-1 tumor cells and treated with various doses of paclitaxel and/or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine, and TILs from lung tissues were harvested as described in the Materials and Methods section. The TILs were stained with various antibodies and the numbers of cytotoxic T cells (CD3+CD8+) and Treg cells (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) in each group were analyzed and counted using flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods section. The ratios of CD8+ T cells/Treg cells were highest in the mice vaccinated with CTGF/E7 DNA and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel compared to those in the other groups. CTGF, connective tissue growth factor.

Generation of antitumor effects with metronomic chemotherapy

We evaluated whether metronomic chemotherapy provided in vivo antitumor effects without the mediation of immunocytes. The antitumor effects of CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination with or without 6 mg/kg paclitaxel in BALB/c nude mice were further tested. BALB/c nude mice that received 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel only (tumor volume, 286.8 ± 18.4 mm3 on day 50) or with CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine (268.3 ± 14.2 mm3 on day 50) had similar smaller tumor sizes than those of naive (712.4 ± 28.3 mm3 on day 50) or those that received only the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine (755.2 ± 23.6 mm3 on day 50) (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 6b). Metronomic chemotherapy generated antitumor effects without T lymphocyte mediation.

Effect of CTGF/E7 DNA combined with metronomic chemotherapy on metastatic tumors

We evaluated whether the DNA vaccine combined with chemotherapy could also control metastatic tumors better than the DNA vaccine alone. Representative figures of pulmonary tumor nodules in C57BL/6 mice are shown in Figure 6c. Mice that received the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine only (number of tumor nodules, 19.4 ± 2.5), CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 3 mg/kg of paclitaxel (10.0 ± 2.0), CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel (4.0 ± 1.0), or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine with 25 mg/kg of paclitaxel (45.4 ± 2.5) had significantly lower numbers of pulmonary tumor nodules than the other groups (naive, 136.0 ± 6.0; 3 mg/kg of paclitaxel only, 131.2 ± 6.2; 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel only, 130.4 ± 9.0; 25 mg/kg paclitaxel only, 117.5 ± 4.5; P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA).C57BL/6 mice treated with CTGF/E7 DNA and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel had the fewest pulmonary tumor nodules compared to those treated with CTGF/E7 DNA only, and CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine plus 3 or 25 mg/kg of paclitaxel (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA). CTGF/E7 DNA combined with metronomic chemotherapy effectively reduced the numbers of metastatic tumors.

CD8+ cytotoxic cell/Treg cell ratio and antitumor effects of CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine combined with metronomic chemotherapy

The ratio of cytotoxic and regulatory T cells was evaluated to determine whether this could reflect the antitumor effects. The CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine combined with 6 mg/kg paclitaxel group had highest cytotoxic/regulatory T cells ratio in TILs compared to the other groups (naive, 0.104 ± 0.004; CTGF/E7, 0.899 ± 0.034; CTGF/E7 plus 3 mg/kg paclitaxel, 2.550 ± 0.112; CTGF/E7 plus 6 mg/kg paclitaxel, 6.696 ± 0.388; CTGF/E7 plus 25 mg/kg paclitaxel, 0.986 ± 0.034, P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 6d). The higher ratios negatively associated with the pulmonary tumor nodules in the CTGGF/E7 DNA only and those with various doses of paclitaxel (Figure 6c,d).

The results indicated that paclitaxel, especially metronomic paclitaxel, enhanced host antitumor T-cell immunity and depleted regulatory T-cell immunity, resulting in antitumor effects of CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination more potent than other dosage regimens. The ratio of CD8+ cytotoxic cells/Treg cells from the TILs reflected the antitumor effects of CTGF/E7 DNA vaccination combined with metronomic chemotherapy.

Discussion

Cytotoxic drugs are proven to kill tumor cells and cure or significantly prolong the lives of cancer patients. They are often administered in single doses or in short courses of therapy at the highest doses possible without causing life-threatening toxicity, referred to as the “MTD.” MTD therapy requires prolonged breaks (generally 2–3 weeks) between successive cycles of therapy because of significant toxic side effects, such as myelo- and immunosuppression. Because chemotherapy suppresses immunity, it is not usually considered for use in combination with immune-related therapies.

T lymphocytes are more susceptible to apoptosis than TC-1 tumor cells when cultured with paclitaxel in in vitro assays (IC50 104 pmol/l for TC-1 and 102 pmol/l for T lymphocytes). With metronomic chemotherapy, comparatively low doses of drugs, significantly below the MTD, are administered, but more frequently than with other dosing regimens. Chemotherapeutic agents administered at low doses reportedly increase immune-mediated tumor destruction through the stimulation of cytotoxic lymphocytes and the induction of mediators that are directly or indirectly involved in cell killing.20 This presumed more effective in terms of reducing toxicity,4 and the antitumor effects may be superior to conventional MTD regimens, especially in some preclinical models.21,22 Unlike MTD chemotherapy, results indicate that metronomic chemotherapy does not lower the antitumor effects of immunotherapy, but significantly enhances antitumor effects in the mouse model studied (Figures 1b,d and 6c).

The antiangiogenic effect was independent of T-cell mediation in this study. Both MTD and metronomic paclitaxel significantly lowered in vivo angiogenesis in both C57BL/6 (Figure 4c) and BALB/c nude (Figure 4d) mice. Thus, the in vivo antiangiogenic effect of chemotherapy occurred regardless of the type of paclitaxel dosing (MTD or metronomic) and was not mediated by T lymphocytes. However, MTD paclitaxel controlled tumor growth better than metronomic paclitaxel (Figure 1c). One explanation is that TC-1 is a rapidly growing tumor, and MTD chemotherapy directly exerts a tumor cytolytic effect and controls tumor growth better than metronomic chemotherapy, which indirectly targets only tumor endothelial cells. Therefore, possible tumor growth inhibition by MTD paclitaxel, as shown by this study, may have an antiangiogenic effects that must be considered.

We found that integration of chemotherapy and immunotherapy generated stronger antitumor effects than immunotherapy alone. The TC-1 tumor model offers an opportunity to test vaccine strategies in the context of targeting human papillomavirus E6 and/or E7 tumor antigen-related diseases, such as cervical cancer. Here, as in previous studies, the E7 chimeric DNA vaccine enhanced E7-specific T-cell immunity, prevented tumor growth, and reduced the number of pulmonary micrometastatic TC-1 tumors in the mouse model.23,24 Nonetheless, we found that the E7 chimeric vaccine only delayed the growth of established tumors (Figure 1d). Antigen-specific tumor vaccines alone have limited potential in treating measurable tumor burden, which highlights the importance of identifying more potent vaccine strategies for cancer therapy in the clinical setting. Our results revealed that MTD paclitaxel inhibited the in vivo antitumor activity of the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine because paclitaxel impaired the proliferation of T cells by stabilizing their microtubules. However, when given in metronomic sequence at immune-modulating doses, paclitaxel enhanced, rather than inhibited, the antitumor immunity generated by the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine to control established tumors (Figure 1d). This finding was not observed in experiments involving only systemic metronomic or MTD chemotherapy (Figure 1c).

Preclinical and clinical data demonstrate increased tumor control with treatment modalities that combine immunotherapy and chemotherapy.25,26 Recently, in murine models of breast cancer, the efficacy of the DNA vaccine targeting Her2/neu was significantly increased when paclitaxel was combined with doxorubicin.27 Thus, chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy is a potential strategy for cancer therapy. Cytotoxic drugs can enhance the antitumor effects of antigen-specific DNA vaccines. Proietti et al. demonstrated that cyclophosphamide enhanced T-cell efficacy against tumors.3 There is also a report suggesting that cyclophosphamide enhanced the antitumor immune response of whole-cell vaccination.28

The ratio of cytotoxic/regulatory T lymphocytes can be used to predict the efficacy of immunotherapy. Our results indicate that the ratio of cytotoxic T cells/Treg cells is associated with the antitumor effects of the antigen-specific DNA vaccine combined with chemotherapy (Figure 6c,d). Cytotoxic T lymphocytes are regarded as major effectors against cancer cells, whereas Treg cells have a clearly established immunosuppressive role capable of thwarting the host's immune response to tumors.29 Curiel et al. reported that Treg cells are capable of suppressing the proliferation of tumor antigen-specific as well as antigen-nonspecific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses.30 Similar phenomena were observed in this survey, which further supports that the ratio of cytotoxic/regulatory T cells is a predictor of host antitumor effect after receiving immunotherapy.

The goal of immunotherapy is the in vivo induction or amplification of functionally active, tumor antigen-specific immune cells capable of eradicating tumor cells. Several strategies, including the use of recombinant immunotoxin, anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody, anti-CTLA-4 blocking antibody, and agonistic antiglucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor mAb31,32 abrogate the suppressive effects of Treg cells. These agents result in the development of tumor-specific effector cells and lead to tumor regression in mice.

Kudo-Saito et al. also demonstrate that multimodal therapy consisting of Treg-cell depletion, vaccination, and local tumor radiation eliminated established tumors in a mouse model.33 Cytotoxic drugs, such as cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel, have been evaluated regarding their influence on Treg cells.34,35,36 Another study suggests that cytotoxic drugs can overcome tolerance and enhance antitumor immunity.37 Our results confirm that metronomic paclitaxel decreases Treg cells and augments in vivo antigen-specific immune responses and antitumor effects induced by chimeric CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine (Figure 6). Other alternative mechanisms, including the recruitment and activation of professional antigen-presenting cells, as well as the enhancement of innate immune responses, also require consideration.

In conclusion, combined treatment with metronomic chemotherapy and antigen-specific chimeric DNA vaccination induced antigen-specific immune responses and antitumor effects that were more potent than other treatment regimens. The combination therapy effectively depleted Treg cells and inhibited angiogenesis. Our results provide an immunologic basis for further testing in cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

TC-1 tumor cell line. The production and maintenance of TC-1 cells was as previously described.38

Preparation of DNA construct and DNA bullet. pcDNA3-CTGF/E7 was prepared as previously described.39 The plasmid construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The preparation of gold particle-coated DNA bullets and the delivery of the DNA vaccine via low pressure-accelerated gene gun (BioWare Technologies, Taipei, Taiwan) was also described previously.18

Cytotoxic drug administration. Paclitaxel (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ), diluted with distilled water was administered to mice via intraperitoneal injection at different doses and scheduled intervals (25 mg/kg twice per week or 3 or 6 mg/kg daily) according to each protocol. Daily 3 and 6 mg/kg paclitaxel was continuously administered until the day of experiments or euthanasia.

In vivo tumor treatment experiments. The treatment protocols of chemotherapy and DNA vaccine are presented in Figure 1a. For the subcutaneous therapeutic experiments, C57BL/6 or BALB/c nude mice (five per group) were challenged with 5 × 104 TC-1 tumor cells/mouse subcutaneously on the right leg to generate subcutaneous tumor nodules in the morning of day 0. In the morning of day 3 after tumor challenge, different doses of paclitaxel were given at different intervals as described earlier, with or without the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine. In the morning of day 7 after tumor challenge, several groups of mice were vaccinated with 2 µg of CTGF/E7 DNA and boosted with the same regimen every 7 days. Perpendicular tumor diameters were measured using Vernier scale calipers, and the tumor volume was calculated using the formula [(x2y)/2] for an ellipsoid. The mice were monitored twice a week and killed if the tumor volume became >800 mm3.

For the intravenous therapeutic experiments, C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were challenged with 5 × 104 TC-1 tumor cells/mouse intravenously via the tail vein to generate a pulmonary metastatic model as described previously.18 Paclitaxel and/or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine were administered according to the aforementioned protocols. The mice were killed 28 days after tumor challenge to examine lung weights and pulmonary tumor nodules.

In vivo Ab depletion experiment. In vivo Ab depletion was performed as described previously.40 Briefly, C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were challenged with TC-1 tumor cells subcutaneously, vaccinated with the CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine, and administered 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel. Ab depletion was started on the day of TC-1 tumor challenge, using mAb GK1.5 for CD4 depletion, mAb 2.43 for CD8 depletion, and mAb PC61 for CD25 depletion.41 Flow cytometry analysis revealed that 95% of the appropriate lymphocyte subsets were depleted, with normal levels of other lymphocyte subsets. Depletion was terminated on the day of euthanasia.

Surface marker staining and flow cytometry. Mice (five per group) first received various doses of paclitaxel as described earlier. They were vaccinated with 2 µg of CTGF/E7 DNA on days 7 and 14 after paclitaxel administration. The mice were killed 7, 14, 21, 28, or 35 days after the last DNA immunization and their splenocytes were harvested. The splenocytes were then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD3, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD4, PE-conjugated anti-CD8, PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD4, or PE-conjugated CD25 Ab (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) for different experiments.40 Cytometric analyses were performed using a Becton Dickinson FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), with CELLQuest software.

Intracellular interferon-γ cytokine staining and flow cytometry. Splenocytes obtained from various vaccinated groups were incubated with 1 µg/ml of major histocompatibility complex I-restricted E7 peptide (aa49–57).40,42,43 Cell surface marker staining of PE-conjugated anti-CD8 and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse interferon-γ (PharMingen) were performed44,45,46 and analyzed by flow cytometry as described earlier.

In vivo angiogenesis assay. In vivo angiogenesis was assessed using the matrigel plug assay with a protocol similar to that described previously.19 Briefly, matrigel (Becton Dickinson) was mixed with heparin (final concentration 50 U/ml) and basic fibroblast growth factor (final concentration, 10 ng/ml). A total of 0.5 ml/mouse of the matrigel mixture was injected subcutaneously into the abdominal midline of C57BL/6 or BALB/c nude mice (five mice/group) on day 0. The mice were given 25 mg/kg of paclitaxel on days 0, 3, and 7, or 3 mg/kg or 6 mg/kg of paclitaxel every day intraperitoneally from days 0 to 10 and/or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine on days 0 and 7. They were killed on day 11.

MVD evaluation. The matrigel plugs were resected and half was fixed in 10% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stains to calculate MVD.19 MVD was determined with ×400 magnification and the mean number of microvessels in the five most vascular fields was calculated and referred to as the MVD.

Detection of Hb content in matrigel. The matrigel plugs were resected as described earlier. Half of these were used to determine the MVD. The remaining half were assayed for Hb content using a Hb detecting kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Human GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany).

Characterization of regulatory T lymphocytes. C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were inoculated intravenously with TC-1 tumor cells (5 × 104/mouse) via the tail vein and treated with various doses of paclitaxel and/or CTGF/E7 DNA vaccine. TILs from lung tissue and splenocytes were harvested on day 28 after TC-1 tumor challenge. The preparation of single cell suspensions from lung tissues was performed as described previously, with modifications.18 Cell surface marker staining of PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD4, PE-conjugated anti-CD25 (PharMingen), and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse Foxp3 Abs (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) were performed as described previously.47 The staining was characterized by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis. All of the data were expressed as mean ± SEM, which represented at least two different experiments. Data for intracellular cytokine staining and tumor treatment experiments were evaluated by ANOVA. The event time distributions for different mice in the survival experiments were compared using log rank analysis. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Department of Medical Research of National Taiwan University Hospital and by grants from the National Science Committee of Taiwan (NSC96-2314-B-002-091MY2 and 98-2628-B-002-083-MY3). The E7-specific CD8+ T cell line and TC-1 tumor cell line were kindly provided by Dr Wu of Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes (Baltimore, MD).

REFERENCES

- Boon T, Cerottini JC, Van den Eynde B, van der Bruggen P., and , Van Pel A. Tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam A, Yacavone RF, Zahurak ML, Johns CM, Pardoll DM, Piantadosi S, et al. Immunomodulatory properties of antineoplastic drugs administered in conjunction with GM-CSF-secreting cancer cell vaccines. Int J Oncol. 1998;12:161–170. doi: 10.3892/ijo.12.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proietti E, Greco G, Garrone B, Baccarini S, Mauri C, Venditti M, et al. Importance of cyclophosphamide-induced bystander effect on T cells for a successful tumor eradication in response to adoptive immunotherapy in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:429–441. doi: 10.1172/JCI1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbel RS, Klement G, Pritchard KI., and , Kamen B. Continuous low-dose anti-angiogenic/ metronomic chemotherapy: from the research laboratory into the oncology clinic. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:12–15. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhail TM., and , Markman M. Paclitaxel in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3:755–766. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.6.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore HC, Green SJ, Gralow JR, Bearman SI, Lew D, Barlow WE, et al. Intensive dose-dense compared with high-dose adjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk operable breast cancer: Southwest Oncology Group/Intergroup study 9623. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1677–1682. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger PK, Dobles M, Tournebize R., and , Hyman AA. Coupling cell division and cell death to microtubule dynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:807–814. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slichenmyer WJ., and , Von Hoff DD. New natural products in cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:770–788. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1990.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthey CL, Brandes ME, Perera PY., and , Vogel SN. Taxol increases steady-state levels of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes and protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1992;149:2459–2465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowinsky EK, Onetto N, Canetta RM., and , Arbuck SG. Taxol: the first of the taxanes, an important new class of antitumor agents. Semin Oncol. 1992;19:646–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier E, Honore S, Pourroy B, Jordan MA, Lehmann M, Briand C, et al. Antiangiogenic concentrations of paclitaxel induce an increase in microtubule dynamics in endothelial cells but not in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2433–2440. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauber N, Parangi S, Flynn E, Hamel E., and , D'Amato RJ. Inhibition of angiogenesis and breast cancer in mice by the microtubule inhibitors 2-methoxyestradiol and taxol. Cancer Res. 1997;57:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Lee CN, Su YN, Chang MC, Hsiao WC, Chen CA, et al. Induction of human papillomavirus type 16-specific immunologic responses in a normal and an human papillomavirus-infected populations. Immunology. 2005;115:136–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disis ML., and , Schiffman K.2001Cancer vaccines targeting the HER2/neu oncogenic protein Semin Oncol 28(6 Suppl 18): 12–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonia SJ, Seigne J, Diaz J, Muro-Cacho C, Extermann M, Farmelo MJ, et al. Phase I trial of a B7-1 (CD80) gene modified autologous tumor cell vaccine in combination with systemic interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2002;167:1995–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondak VK, Liu PY, Tuthill RJ, Kempf RA, Unger JM, Sosman JA, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy of resected, intermediate-thickness, node-negative melanoma with an allogeneic tumor vaccine: overall results of a randomized trial of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2058–2066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Lee JH, He L, Boyd DA, Hardwick JM, Hung CF, et al. Modification of professional antigen-presenting cells with small interfering RNA in vivo to enhance cancer vaccine potency. Cancer Res. 2005;65:309–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CY, Chen CA, Huang CY, Chang MC, Lee CN, Su YN, et al. IL-6-encoding tumor antigen generates potent cancer immunotherapy through antigen processing and anti-apoptotic pathways. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1890–1897. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Hung CF, Chai CY, Hsu KF, He L, Ling M, et al. Tumor-specific immunity and antiangiogenesis generated by a DNA vaccine encoding calreticulin linked to a tumor antigen. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:669–678. doi: 10.1172/JCI12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick RJ, Benveniste RE, Gagliardi TD, Wiltrout TA, Busch LK, Bosche WJ, et al. Nucleocapsid protein zinc-finger mutants of simian immunodeficiency virus strain mne produce virions that are replication defective in vitro and in vivo. Virology. 1999;253:259–270. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello L, Carrabba G, Giussani C, Lucini V, Cerutti F, Scaglione F, et al. Low-dose chemotherapy combined with an antiangiogenic drug reduces human glioma growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7501–7506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini F, Paul S, Mancuso P, Monestiroli S, Gobbi A, Shaked Y, et al. Maximum tolerable dose and low-dose metronomic chemotherapy have opposite effects on the mobilization and viability of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4342–4346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Hung CF, Lin KY, Ling M, Juang J, He L, et al. CD8+ T cells, NK cells and IFN-γ are important for control of tumor with downregulated MHC class I expression by DNA vaccination. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1311–1320. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung CF, Cheng WF, He L, Ling M, Juang J, Lin CT, et al. Enhancing major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation by targeting antigen to centrosomes. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2393–2398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak AK, Robinson BW., and , Lake RA. Synergy between chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of established murine solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4490–4496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welt S, Ritter G, Williams C, Jr, Cohen LS, Jungbluth A, Richards EA, et al. Preliminary report of a phase I study of combination chemotherapy and humanized A33 antibody immunotherapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1347–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eralp Y, Wang X, Wang JP, Maughan MF, Polo JM., and , Lachman LB. Doxorubicin and paclitaxel enhance the antitumor efficacy of vaccines directed against HER 2/neu in a murine mammary carcinoma model. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R275–R283. doi: 10.1186/bcr787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berd D, Maguire HC., Jr, and , Mastrangelo MJ. Induction of cell-mediated immunity to autologous melanoma cells and regression of metastases after treatment with a melanoma cell vaccine preceded by cyclophosphamide. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2572–2577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degl'Innocenti E, Grioni M, Capuano G, Jachetti E, Freschi M, Bertilaccio MT, et al. Peripheral T-cell tolerance associated with prostate cancer is independent from CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:292–300. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DJ, Jr, Felipe-Silva A, Merino MJ, Ahmadzadeh M, Allen T, Levy C, et al. Administration of a CD25-directed immunotoxin, LMB-2, to patients with metastatic melanoma induces a selective partial reduction in regulatory T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:4919–4928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8372–8377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533209100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo-Saito C, Schlom J, Camphausen K, Coleman CN., and , Hodge JW. The requirement of multimodal therapy (vaccine, local tumor radiation, and reduction of suppressor cells) to eliminate established tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4533–4544. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audia S, Nicolas A, Cathelin D, Larmonier N, Ferrand C, Foucher P, et al. Increase of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood of patients with metastatic carcinoma: a Phase I clinical trial using cyclophosphamide and immunotherapy to eliminate CD4+ CD25+ T lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiringhelli F, Menard C, Puig PE, Ladoire S, Roux S, Martin F, et al. Metronomic cyclophosphamide regimen selectively depletes CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and restores T and NK effector functions in end stage cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0225-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevs J, Fakler J, Eisele S, Medinger M, Bing G, Esser N, et al. Antiangiogenic potency of various chemotherapeutic drugs for metronomic chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2004;24 3a:1759–1763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Nomoto K, Himeno K., and , Takeya K. Immune response to syngeneic or autologous testicular cells in mice. I. Augmented delayed footpad reaction in cyclophosphamide-treated mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1979;38:211–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KY, Guarnieri FG, Staveley-O'Carroll KF, Levitsky HI, August JT, Pardoll DM, et al. Treatment of established tumors with a novel vaccine that enhances major histocompatibility class II presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 1996;56:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Chang MC, Sun WZ, Lee CN, Lin HW, Su YN, et al. Connective tissue growth factor linked to the E7 tumor antigen generates potent antitumor immune responses mediated by an antiapoptotic mechanism. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1007–1016. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CW, Chen CA, Lee CN, Su YN, Chang MC, Syu MH, et al. Fusion protein vaccine by domains of bacterial exotoxin linked with a tumor antigen generates potent immunologic responses and antitumor effects. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9089–9098. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Saio M, Nonaka K, Suwa T, Umemura N, Ouyang GF, et al. Depletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells enhances interleukin-2-induced antitumor immunity in a mouse model of colon adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Chen LK, Chen CA, Chang MC, Hsiao PN, Su YN, et al. Chimeric DNA vaccine reverses morphine-induced immunosuppression and tumorigenesis. Mol Ther. 2006;13:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.06.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CA, Chang MC, Sun WZ, Chen YL, Chiang YC, Hsieh CY, et al. Noncarrier naked antigen-specific DNA vaccine generates potent antigen-specific immunologic responses and antitumor effects. Gene Ther. 2009;16:776–787. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Hung CF, Hsu KF, Chai CY, He L, Polo JM, et al. Cancer immunotherapy using Sindbis virus replicon particles encoding a VP22-antigen fusion. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:553–568. doi: 10.1089/10430340252809847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Hung CF, Pai SI, Hsu KF, He L, Ling M, et al. Repeated DNA vaccinations elicited qualitatively different cytotoxic T lymphocytes and improved protective antitumor effects. J Biomed Sci. 2002;9 6 Pt 2:675–687. doi: 10.1159/000067285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Lee CN, Chang MC, Su YN, Chen CA., and , Hsieh CY. Antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes generated from a DNA vaccine control tumors through the Fas-FasL pathway. Mol Ther. 2005;12:960–968. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roord ST, de Jager W, Boon L, Wulffraat N, Martens A, Prakken B, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation in autoimmune arthritis restores immune homeostasis through CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Blood. 2008;111:5233–5241. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]