Abstract

Background

Little is known about the relationship between intrinsic cardiac nerve activity (ICNA) and spontaneous arrhythmias in ambulatory animals.

Methods and Results

We implanted radiotransmitters to record extrinsic cardiac nerve activity (ECNA, including stellate ganglion nerve activity, SGNA; vagal nerve activity, VNA) and ICNA (including superior left ganglionated plexi nerve activity, SLGPNA; ligament of Marshall nerve activity, LOMNA) in 6 ambulatory dogs. Intermittent rapid left atrial pacing was performed to induce paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) or atrial tachycardia (PAT). The vast majority (94%) of LOMNA were preceded or co-activated with ECNA (SGNA or VNA), whereas 6% of episodes were activated alone without concomitant SGNA or VNA. PAF and PAT were invariably (100%) preceded (<5 s) by ICNA. Most of PAT events (89%) were preceded by ICNA and sympathovagal co-activation, whereas 11% were preceded by ICNA and SGNA-only activation. Most of PAF events were preceded only by ICNA (72%); the remaining 28% by ECNA and ICNA together. Complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAEs) were observed during ICNA discharges that preceded the onset of PAT and PAF. Immunostaining confirmed the presence of both adrenergic and cholinergic nerve at ICNA sites.

Conclusions

There is a significant temporal relationship between ECNA and ICNA. However, ICNA can also activate alone. All PAT and PAF episodes were invariably preceded by ICNA. These findings suggest that ICNA (either alone or in collaboration with ECNA) is an invariable trigger of paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmias. ICNA might contaminate local atrial electrograms, resulting in CFAE-like activity.

Keywords: nervous system, autonomic, atrium, arrhythmia, ligament of Marshall

The ligament of Marshall (LOM) contains both nerve and muscle fibers.1–3 Sympathetic nerves from the middle cervical and stellate ganglia pass along the LOM to innervate the left ventricle.4 Parasympathetic nerve fibers from the vagus nerve traverse the LOM and innervate the left atrium (LA), left pulmonary veins (PVs), coronary sinus and posterior left atrial fat pads.5 The close anatomical association between nerves and muscle fibers suggest that they might work synergistically to generate atrial arrhythmia. This latter hypothesis was supported by direct vein of Marshall cannulation and recording in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).6, 7 Doshi et al3 showed that the LOM is a source of adrenergic atrial arrhythmia. However, because nerve activities were not recorded in that study, it is unclear if spontaneous nerve discharges can induce atrial tachyarrhythmias, including atrial tachycardia (AT) and AF, in ambulatory animal models. Recently, we developed methods to continuously record from the stellate ganglion and vagus nerve.8, 9 Using these methods, Tan et al10 showed that extrinsic cardiac nerve activity (ECNA) in the form of simultaneous sympathovagal discharges preceded the onset of paroxysmal AT and AF in 73% of the episodes. However, the triggers of the remaining atrial tachyarrhythmia episodes are unclear. In addition to the extrinsic cardiac nervous system, there is also an extensive intrinsic cardiac nervous system that forms ganglionated plexi (GP) in the heart.11 It is possible that these intrinsic cardiac nerves can activate independently of the ECNA and contribute to atrial arrhythmogenesis. To determine the importance of intrinsic cardiac nerve activity (ICNA) in triggering atrial arrhythmias, it is necessary to directly record ICNA in ambulatory animal models of atrial arrhythmias, and to correlate the nerve discharges with the onset of arrhythmias. We therefore recorded ligament of Marshall nerve activity (LOMNA) and superior left ganglionated plexi nerve activity (SLGPNA) to determine the timing and magnitudes of ICNA. We also simultaneously recorded from the ECNA, including both the stellate ganglion nerve activity (SGNA) and vagal nerve activity (VNA). We then used intermittent pacing to facilitate the development of spontaneous paroxysmal AT and AF in the same dogs.10 The data were analyzed to test the hypothesis that ICNA invariably precedes paroxysmal AT and AF in ambulatory dogs.

Materials and Methods

The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Indiana University School of Medicine, and conforms to the guidelines of the American Heart Association. Male mongrel dogs (N=8, 22 to 27kg) were used in this study. The first two dogs were used for a preliminary study during sinus rhythm to test the feasibility of ECNA and ICNA recordings. The remaining 6 dogs underwent rapid atrial pacing to induce paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmias.

Implantable Radiotransmitters

We used two different types of Data Sciences International (DSI) radiotransmitters in this study: model D70-EEE, which was used in previous studies for SGNA and VNA recordings,9, 10 and a new DSI SNA-beta transmitter. The latter transmitter has a wider bandwidth and a higher sampling rate (5 KHz) but a shorter battery life than the standard DSI transmitter. To verify that DSI SNA-beta is capable of recording nerve activities, we implanted two DSI radiotransmitters in the first dog for preliminary study. The bipolar wires from both transmitters were connected to the same right stellate ganglion. The dog was allowed to recover and recordings were made while the dog was ambulatory. As shown in Figure 1 of the Online Supplement, both transmitters were adequate in recording SGNA, and that SGNA recorded by both transmitters preceded the abrupt onset of sinus tachycardia in 97% of the episodes.

Surgical procedures

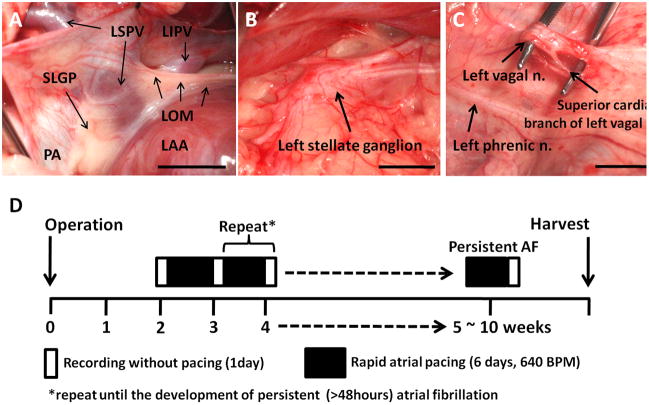

Left thoracotomy was performed through the fourth intercostal space under isoflurane general anesthesia. Figure 1A shows the relative anatomical locations of SLGP, LOM, left superior PV (LSPV), left inferior PV (LIPV), pulmonary artery and left atrial appendage (LAA). A pair of bipolar wires was placed in the middle portion of the LOM and was connected to a DSI SNA beta transmitter (which has only 1 recording channel) located in a subcutaneous pocket. A D70-EEE transmitter was used to record stellate ganglion nerve activity (SGNA) from the left stellate ganglion (Figure 1B), vagal nerve activity (VNA) from the superior cardiac branch of the left vagal nerve (Figure 1C) and SLGPNA. A pacing lead was implanted onto the LAA and connected to a subcutaneously positioned modified Medtronic Kappa pacemaker (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) for intermittent high rate atrial pacing.10

Figure 1.

Recording sites and the study protocol. A, Ligament of Marshall (LOM) and superior left ganglionated plexi (SLGP). The LOM originates from coronary sinus and connects to left superior pulmonary vein (LSPV). SLGP is located between left atrial appendage (LAA) and LSPV. B, Left stellate ganglion. C, Superior cardiac branch of the left vagal nerve. D, Diagram of study protocol. LOM, ligament of Marshall; LSPV, left superior pulmonary vein; LIPV, left inferior pulmonary vein; SLGP, superior left ganglionated plexi; PA, pulmonary artery; LAA, left atrial appendage

Pacing Protocol

Six dogs underwent rapid atrial pacing to induce paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmia. After two weeks of post-operative recovery, the DSI transmitters were turned on to record baseline rhythm for one day (Figure 1D). Baseline is the observational period before the commencement of pacing. High rate (640 bpm, twice the diastolic threshold) atrial pacing was then given for 6 days followed by one day of monitoring during which the pacemaker was turned off. The rhythm was monitored for 24 hrs to determine the presence of AF. The alternating pacing-monitoring sequence was repeated until persistent (>48 hours) AF was documented. The dogs were monitored for an average of 79 ± 20 days (range 57 to 105) before being euthanized. The heart and stellate ganglia were harvested for histological analysis.

Data Analysis

The signals were manually analyzed to determine the temporal relationship among nerve activities, heart rate changes, and the occurrence of atrial tachyarrhythmia. In all dogs studied, we manually determined the presence or absence of nerve activities at all channels. Nerve activities were considered present if there was a 3-fold increase in the amplitude over baseline noise. When the activation of two nerve structures overlaps with each other, we consider these two nerve activities co-activated. The nerve activity is considered to precede the onset of paroxysmal AT or AF if there was nerve activity within 1 s prior to the onset of these arrhythmias. The nerve activities are considered associated if they either discharge simultaneously (co-activation) or activate alternatively to each other. Actual examples of association will be shown in the Results section. Paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmia was defined as an abrupt (>50 bpm/s) increase in the atrial rate to >200 bpm that persisted for at least 5 s.12 If tachyarrhythmias were regular, we call them paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (PAT) episodes. The irregular tachycardias were called paroxysmal AF (PAF) episodes. In addition to manual analyses, custom-designed software was used to automatically import, filter, rectify and calculate the integrated nerve activities (Int-NA). Hilbert transforms were used to convert the filtered ECG signals into its instantaneous amplitudes and frequencies.13 A band-pass (30–500 Hz) filter was applied to the atrial electrograms before manual analyses of the complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAE), defined as fractionated potentials exhibiting multiple deflections from the isoelectric line (≥ 3 deflections) and/or potentials with continuous electrical activity without isoelectric periods.14 We did not directly record a surface ECG. Instead, we applied band-pass filtering (5–100 Hz) on the VNA recording to obtain an electrocardiogram for analyses.10 We also band-pass filtered the SLGP signals from 5 Hz to 100 Hz to obtain bipolar local left atrial electrograms.

Histology

Tissue samples were obtained from the recording sites and fixed in 4% formalin for 45 min to an hour, followed by storage in 70% alcohol.15 The tissues were paraffin embedded and cut perpendicularly to the atrioventricular groove according to method published by Makino et al16 5-μm sections were stained with antibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) using mouse monoclonal anti-TH (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY), Cholineacetyltransferase (ChAT) using goat anti-ChAT polyclonal antibody and growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43) using mouse anti-GAP43 monoclonal Antibody (both from Chemicon, Billerica, MA).

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SD. Paired t-test was used to compare the Int-NA or the incidence of arrhythmia before and after rapid atrial pacing. Cosinor analysis was used to test the circadian variation of Int-NA.17 A P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Simultaneous Recording of LOMNA, SGNA and VNA

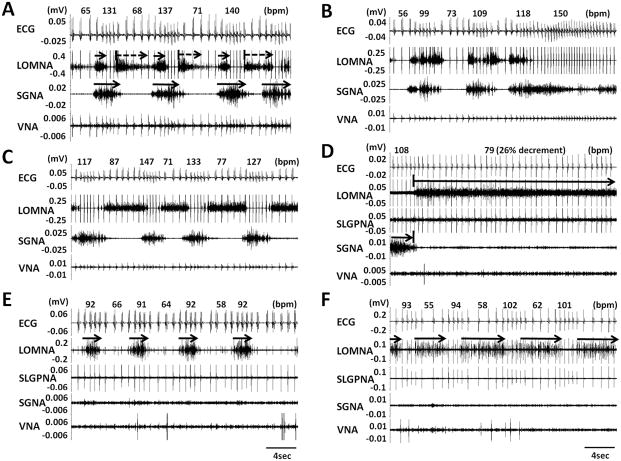

All dogs survived the surgery and without complications. Simultaneous recording of ICNA and extrinsic cardiac nerve activity (ECNA) was successful in all dogs studied. Figure 2A–2C came from dog 2 (preliminary study), in which we attempted to simultaneously record LOMNA with SGNA, VNA and a subcutaneous ECG during sinus rhythm. Figure 2A shows that a short burst of SGNA (first solid arrow) was associated with tachycardia while SGNA withdrawal followed by LOMNA activation was associated with abrupt reduction of heart rate (first dashed arrow). Figure 2B shows that simultaneous SGNA and LOMNA discharges were associated with heart rate acceleration to 154 ± 13% of the baseline rate. In this episode, SGNA preceded LOMNA by < 1 s. In contrast to the simultaneous activations, Figure 2C shows an example of alternating SGNA and LOMNA. The latter was associated with a reduction of heart rate to 46 ± 10% of the baseline rate. In spectrum analysis, ICNA at the LOM showed a wide frequency content of up to 1300 Hz.

Figure 2.

Examples of intrinsic and extrinsic cardiac nerve activity recorded simultaneously. A, Simultaneous ECG, SGNA, LOMNA and VNA recordings showing burst SGNA (arrows on SGNA) occurred alternatively with burst discharges on LOMNA. B, LOMNA preceded (within 1 s) by or co-activated with SGNA discharges suggesting that LOMNA were sympathetic. C, LOMNA activated alternatively with SGNA, leading to a reduction and an increase of HR suggesting that LOMNA contains parasympathetic nerve activity. D, Continuous activation patterns of LOMNA. After SGNA withdrawal, LOMNA started to fire continuously for 81 s during which there was persistent heart rate reduction. Without SGNA and VNA discharges, cyclic pattern of ICNA alone may be associated with either HR acceleration (E) or deceleration (F).

Simultaneous Recording of LOMNA, SLGPNA, SGNA and VNA

With the success in dog 2, we added SLGPNA recording and rapid atrial pacing protocol in subsequent 6 dogs (dogs 3–8). In these studies, the DSI SNA-beta radiotransmitter was used to record LOMNA and the D70-EEE radiotransmitter was used to record SGNA, VNA and SLGPNA simultaneously. In addition, we performed intermittent rapid pacing to induce PAF. We found three types of LOMNA: 1) continuous (≥ 10sec continuous discharges, Figure 2D), 2) sporadic (irregular discharges, Figure 2A, 2B and 2C) and 3) cyclic patterns (regular intermittent activations that repeat itself more than 3 times, Figure 2E and 2F). We analyzed 84 segments of LOMNA activities. Among them, 60 (71%) showed sporadic pattern, 22 (26%) showed continuous pattern and only 2% showed cyclic patterns. Note that the same cyclic patterns are also infrequently observed in the SGNA.9 Figure 2D shows example of continuous pattern of LOMNA discharges that occurred immediately after termination of SGNA. The LOMNA was associated with a reduction of heart rate from 108 to 79 bpm (26% decrement). Figure 2E and 2F show two cyclic patterns of LOMNA, which were associated with heart rate increment from 63 to 92 bpm (31% increment) and heart rate decrement from 97 to 57 bpm (41% decrement), respectively.

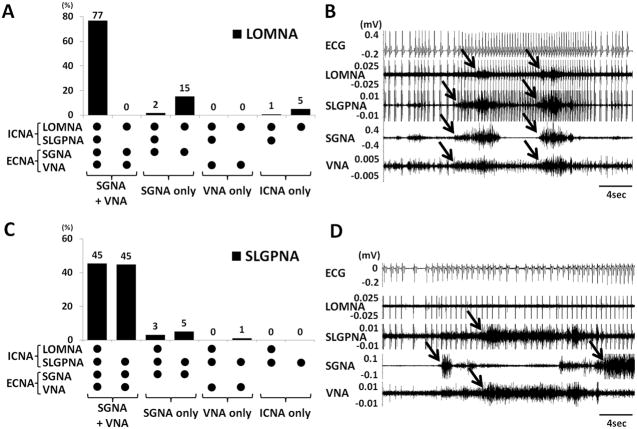

In randomly selected 1800 30-s segments (15 hrs) at baseline, LOMNA and SLGPNA were detected in 7.5% (135 events) and 17.1% (308 events) of the 30-s windows, respectively. In 210 selected windows with LOMNA, the vast majority (94%) were associated with ECNA (SGNA or VNA, Figure 3A). The association can be either simultaneous discharges (such as Figure 2B) or alternating discharges (such as Figures 2A, 2C and 2D). Among them, 161 windows (77%) were associated with sympathovagal co-activation and 36 (17%) were preceded (<1 s) by SGNA-only (no VNA). In no episodes did VNA-only preceded or co-activated with LOMNA. Figure 3A shows the summary of all different patterns of co-activation. An example of the most common pattern (first column) was shown in Figure 3B. In the remaining 6% of episodes, LOMNA activated alone without concomitant SGNA or VNA discharges (as shown in Figures 2E and 2F). SLGPNA also showed a temporal association with the other nerve activities. Most of the SLGPNA were preceded by or co-activated with ECNA, including sympathovagal co-activation (139 windows, 90%), SGNA-only (13 windows, 8%) and VNA only (2 windows, 1%). A summary of all patterns is shown in Figures 3C. An example of a common pattern (column 2) is shown in Figure 3D. We also noted that in 75 episodes (49%), the SLGPNA co-activated with LOMNA, whereas in 79 events (51%) the SLGPNA did not co-activate with LOMNA.

Figure 3.

Relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic cardiac nerve activities. A shows that most (94%) of the LOMNA occurred in association with either SGNA or VNA, but occasionally (6%) the LOMNA occurred in the absence of either SGNA or VNA. B, Examples of LOMNA preceded by sympathovagal and SLGPNA co-activation. C shows that SLGPNA always occurs with the ECNA. We found no incidence in which SLGPNA acted alone. D shows an example in which SLGPNA, SGNA and VNA occurred together, while LOMNA was not observed. Arrows indicate the nerve activity.

To validate the above analyses, we randomly selected 72 different 30-s time segments per dog, or 576 segments from 8 dogs. LOMNA and SLGPNA were detected in 7.8% (45 events) and 16.0% (92 events) of the 30-s windows, respectively. This sensitivity was not significantly different from the data presented in the beginning of the previous paragraph. In these time segments, we also found that the vast majority of LOMNA and SLGPNA were associated with the ECNA.

ECNA and ICNA Preceding the Onset of Paroxysmal Atrial Tachyarrhythmia

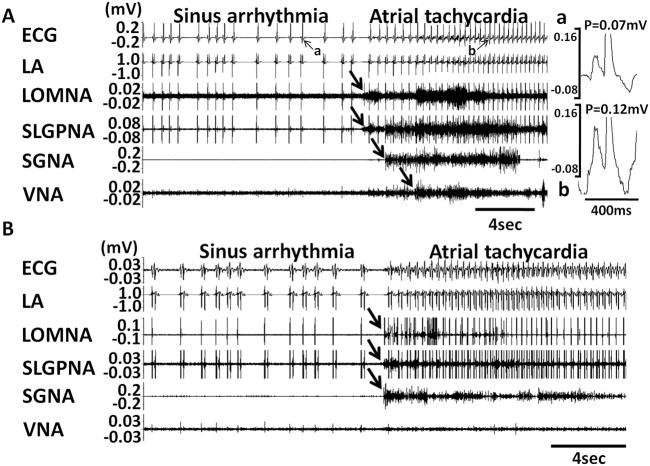

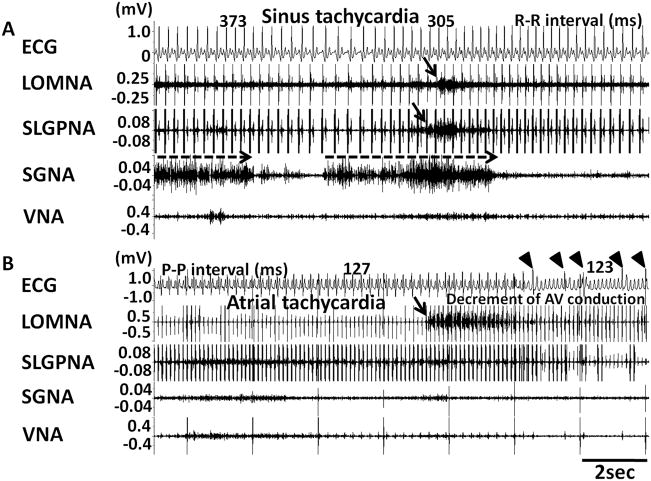

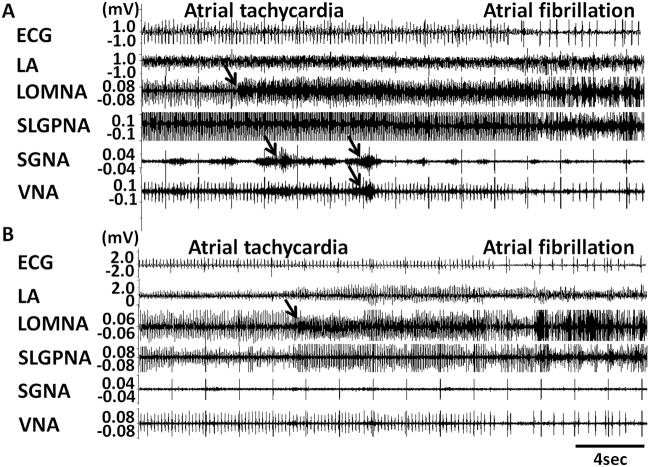

Five of 6 dogs developed persistent AF after 39 ± 24 days of rapid pacing (range 20 to 72 days). The remaining dog was sacrificed after 57 days because of pacemaker battery depletion. All dogs displayed spontaneous PATs before the development of persistent AF. The PAT episodes per dogs increased from 6 ± 2 episodes per day at baseline to 14 ± 5 episodes after pacing (p=0.004). The intra-subject change was 8 ± 4 between baseline and after pacing. Of 164 episodes of PAT, 89% were preceded (< 5 s) by ICNA and sympathovagal co-activation, whereas 11% were preceded by ICNA and SGNA, without VNA. Figures 4A and 4B show typical examples of PAT episodes preceded by autonomic nerve activities. The magnified pseudo ECG shows the differences of p wave morphologies between sinus rhythm (Figure 4Aa) and PAT (Figure 4Ab). The PAT in Figure 4A was preceded by ICNA co-activated with sympathovagal discharges. The PAT in Figure 4B was preceded by ICNA and SGNA (black arrows) but not VNA. Same as these two examples, all PAT episodes were preceded by ICNA. LOMNA alone never induced PAT, although it may induce sinus tachycardia (< 200 bpm). If SGNA induced sinus tachycardia, additional ICNA discharges may further accelerate heart rate. The same occurs during PAT episodes. ICNA discharges during tachycardia may influence the heart rate. Although heart rate was increased by SGNA, combined SGNA and ICNA can further accelerate the sinus tachycardia (Figure 5A). We also found that LOMNA may exert the same effects on the rate of atrial tachycardia. Figure 5B shows an example in which LOMNA accelerated atrial rate from 472 bpm to 485 bpm, leading to a paradoxical reduction of ventricular rate due to reduced atrioventricular conduction. The nerve activity patterns of PAT to PAF conversion (N=29 episodes) appear to be different than that associated with PAT initiation. We found that 28% PAT to PAF conversion were preceded by co-activation of ICNA and sympathovagal discharges (Figure 6A) and 72% by ICNA alone (Figure 6B).

Figure 4.

Induction of PAT by extrinsic and intrinsic cardiac nerve activities. A shows an example in which ICNA occurred before ECNA and a PAT episode. The magnified pseudo ECG shows the different P wave morphologies during sinus rhythm (Aa) and during PAT (Ab). B shows simultaneous ICNA and SGNA leading to the onset of PAT.

Figure 5.

ICNA and heart rate acceleration during pre-existing sinus tachycardia. A shows sinus tachycardia following SGNA (dashed arrows). ICNA (downward arrows) induced further shortening of R-R intervals. Panel B shows LOMNA (downward arrow) during pre-existing atrial tachycardia resulted in shortening of atrial cycle length and paradoxical decrement of atrioventricular (AV) conduction. The arrowheads indicate the conducted QRS complexes.

Figure 6.

Cardiac nerve activities and conversion from PAT to PAF. Although 28% of PAF was preceded by co-activation of ECNA and ICNA (A), the vast majority of PAF events (72%) were preceded only by ICNA (B). Arrows indicate the nerve activities

Increased ECNA and ICNA after Intermittent Atrial Pacing

Intermittent atrial pacing increased 24-hr Int-NA on all channels. The Int-SGNA increased from 2.3 ± 1.3 mV-s at baseline to 2.6 ± 1.3 mV-s after pacing (p=0.022). The Int-VNA increased from 0.7 ± 0.3 mV-s at baseline to 0.8 ± 0.2 mV-s after pacing (p=0.001). The Int-SLGPNA increased from 0.7 ± 0.4 mV-s at baseline to 2.2 ± 2.0 mV-s after pacing (p<0.001). The Int-LOMNA increased from 3.8 ± 2.5 mV-s at baseline to 5.9 ± 1.0 mV-s after pacing (p<0.001). As shown in Online Supplement Figure 2, the Int-SGNA increased primarily during day time. However, the Int-VNA, Int-SLGPNA and Int-LOMNA showed an overall increase of nerve discharges (p<0.001), but the increment occurred in both day and night times. The intra-subject change was 0.2 ± 0.4 mV-s, 0.1 ± 0.2 mV-s, 1.6 ± 1.7 mV-s and 1.9 ± 1.3 mV-s for Int-SGNA, Int-VNA, Int-SLGPNA and Int-LOMNA, respectively. Cosinor analysis showed significant circadian variation of SGNA (but not VNA, SLGP and LOMNA) at baseline and after pacing. We also analyzed the effects of pacing duration on the change of Int-NA (Online supplementary Figure 2). All Int-NAs increased after pacing, but the ICNA doubled its baseline value earlier than ECNA (SLGPNA and LOMNA with 1~ 2 weeks, SGNA and VNA with 3 ~ 4 weeks), suggesting earlier remodeling of ICNA than ECNA during rapid LA pacing (Online supplementary Figure 3).

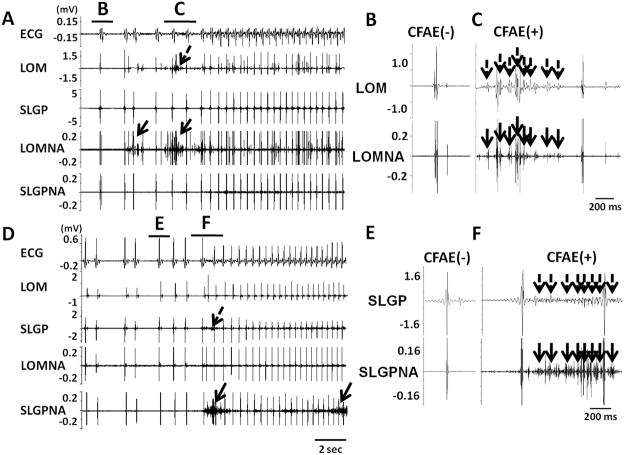

CFAE and ICNA

We analyzed 174 episodes of PAT or PAF for the presence of CFAE. Among them, 27 episodes were at baseline and 147 episodes after pacing, respectively. We also analyzed 174 control (non-PAT/PAF) time segments. CFAE was noted in the LOM and SLGP in 141 (81%) and 105 (60%) of the PAT or PAF episodes, respectively. Eighty five PAT or PAF episodes (49%) were preceded by CFAE both at the LOM and SLGP. In 174 control time segments, however, only 10 of 174 (6%) showed CFAE in LOM (p<0.001 compared with 141 of 174) and 15 of 174 (9%) showed CFAE in SLGP (p<0.001 compared with 105 of 174). Figure 7A shows an example that documents CFAE at the LOM (dashed arrows) preceding the onset of a PAT episode by more than 2 seconds. Rapid nerve activities (solid arrows) were seen prior to or occurred simultaneously with the CFAE. Figures 7B and 7C show magnified views of the time segments B and C, respectively. Multiple complex deflections (dashed arrows) in Panel C are consistent with CFAE, which occurred simultaneously with the nerve activities in the LOM. Because the SLGP recording showed no fractionated potentials, there is no evidence of cross talk between recording channels. Figures 7D shows representative CFAE at the SLGP prior to the onset of PAT. SLGPNA (solid arrows) and CFAE (dashed arrows) preceded the onset of PAT. A second arrow on SLGPNA indicates continuous nerve activity during PAT. Panels E and F show enlarged time segments E and F in Figure 7D. The incidence of PAT/PAF episodes with preceding CFAE at the LOM increased after rapid pacing as compared to baseline (91% vs. 44%, p<0.001), whereas CFAE at the SLGP did not show significant difference between baseline and post-pacing period (63% vs. 60%, p=0.509).

Figure 7.

ICNA and CFAE at the onset of PAT. A, Local LOM electrograms showed CFAE like signals (dashed arrows) before the onset of PAT episode. The time segments B and C are shown in greater detail in panels B and C, respectively. D, SLGP electrograms show CFAE like signals (dashed arrows) before the onset of a PAT episode. CFAE signals at SLGP occurred simultaneously with SLGPNA (arrows). The time segments E and F are shown in greater detail in panels E and F, respectively.

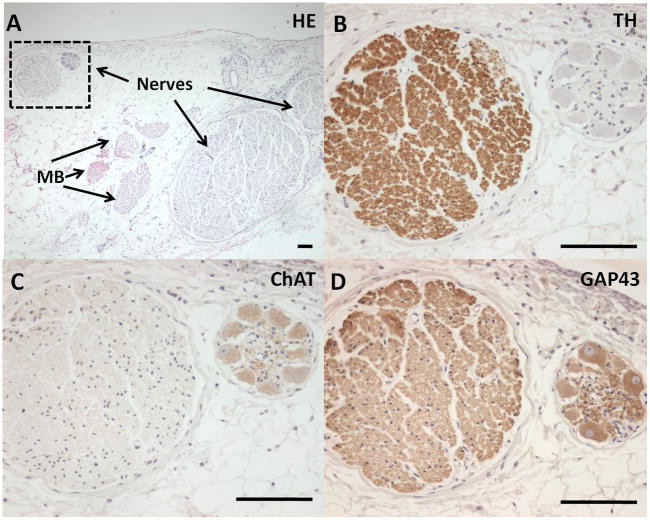

Histological Examinations

Immunohistochemical staining of the LOM showed abundant nerve structures co-localized with the Marshall bundle (Figure 8A). There are both adrenergic (tyrosine hydroxylase positive, Figure 8B) and cholinergic (cholineacetyltransferase positive, Figure 8C) nerve bundles. Growth associated protein 43 (GAP43) staining were positive in both adrenergic and cholinergic nerves, consistent with active axonal growth (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Histological sections of the LOM recording sites. A shows the hematoxylin and eosin staining. There are nerves and Marshall bundles (MB) in this section. The area marked by a square contains two large nerve bundles. TH staining (B) and ChAT staining (C) showed that these nerve bundles were adrenergic and cholinergic, respectively. Both nerve bundles stained positive with GAP43 staining (D), suggesting active nerve sprouting. Bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that 1) it is feasible to simultaneously record the ICNA and ECNA in ambulatory canine models of atrial tachyarrhythmia; 2) most ICNA showed a close temporal relationship with ECNA, indicating communication between these two systems; 3) a small number of ICNA activated without a temporal relationship with ECNA, suggesting that ICNA may be independently arrhythmogenic; 4) ICNA activation may be associated with either tachycardia or bradycardia, suggesting that the adrenergic and cholinergic nerves within the ICNA can activate independently from each other; 5) ICNA always precedes the onset of PAT and PAF episodes, suggesting that ICNA is an invariable trigger of paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmias in this model; and 6) CFAE on the local electrogram occurred coincidentally with ICNA.

Interaction between ICNA and ECNA

The canine extrinsic and intrinsic cardiac nervous systems are known to be anatomically similar to those in humans.18 It was possible to record ECNA in ambulatory dogs and to correlate the changes of ECNA to arrhythmogenesis.8–10 However, whether or not ECNA acted alone or activated together with ICNA to induce arrhythmia remains unclear. Intrinsic cardiac neurons receive inputs from both the spinal cord and medullary neurons.19 Studies in anesthetized animals suggested that GPs modulate the autonomic interactions between extrinsic and intrinsic cardiac nerve structures.20 Consistent with these observations, we showed that there are frequent interactions between ECNA and ICNA and that in a majority of the time, these two nervous systems seem to activate together. In a small percentage of incidences, the ICNA could activate alone without the inputs from ECNA. If ICNA activates alone, then it is possible that ICNA plays an important and independent role in cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Tan et al10 previously reported that sympathovagal co-activation preceded the onset of PAT and PAF in 73% of episodes. In the remaining 27% of episodes, there were no apparent ECNA triggers for the atrial tachyarrhythmia. The present study reproduced those results because 151 out of 193 PAT and PAF episodes (78%) were preceded by sympathovagal co-activation. If we do not consider the results of ICNA recordings, 22% of the episodes would not have an apparent autonomic trigger. On the other hand, if we include the ICNA recordings, then 100% of the PAT and PAF episodes were preceded by autonomic nerve discharges. Among the atrial tachycardia episodes, the PAT was more often preceded by simultaneous activation of ECNA and ICNA, whereas PAT to PAF conversion was more often associated with ICNA alone. These findings suggest that ICNA is an invariable trigger of atrial tachyarrhythmias in this model.

Importance of ICNA in Atrial Fibrillation

AF is characterized by two co-existing mechanisms (focal pulmonary vein discharges and atrial reentry).21, 22 Ibutilide is effective in suppressing reentry but not focal discharges. However, GP ablation is effective in suppressing the focal discharges, resulting in regularization of electrograms in both atria before termination.21 These findings suggest that autonomic remodeling produced by prolonged rapid atrial pacing23–25 is important in the mechanisms of AF in this model. In addition to the heterogeneous neural remodeling and nerve sprouting, we demonstrated in the present study a direct temporal relationship between ICNA and spontaneous onset of AF. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the association between cardiac arrhythmia and nerve activity of the ventral lateral cardiac nerve and the GP near the LOM.26–29

Neural mechanism of CFAE

CFAE is frequently observed in human AF, and ablation aimed at the CFAE sites may terminate AF.14 Lu et al30 hypothesized that CFAE may be caused by enhanced activity of the intrinsic cardiac autonomic nervous system. Lellouche et al31 reported that fractionated electrogram in sinus rhythm is strongly associated with parasympathetic responses during AF ablation, suggesting that parasympathetic activation during AF ablation is associated with the presence of pre-ablation high-amplitude fractionated electrograms in sinus rhythm. Local acetylcholine release might explain this phenomenon. While fractionated electrograms might represent atrial activity induced by underlying nerve structures, it is also possible that ICNA is itself a part of the local atrial electrograms. In the present study we were able to measure ICNA directly at the sites with CFAE. We found that both CFAE and ICNA were recorded simultaneously at the onset of PAT/PAF episodes. Our findings confirmed an association between CFAE and ICNA as suggested by other investigators.30, 31 The mechanism of CFAE could be due to either rapid activity of the cardiac myocytes, or due to both the activation of myocytes and the activation of intrinsic cardiac nerves. In the latter situation, the electrical activity of the nerves forms a part of the intracardiac electrograms.

Clinical Implications

Recent study by Pokushalov et al32 showed that selective GP ablation directed by high-frequency stimulation does not eliminate paroxysmal AF in the majority of patients. This finding suggests that high-frequency stimulation is not a highly accurate method to locate the GPs. In order to more completely and efficiently locate the GPs, direct nerve recording might be necessary. In the present study, we report the feasibility of GP recordings, and show that GP activation is an invariable trigger of paroxysmal AT and AF. These findings suggest GP recordings followed by ablation might prove more reliable to locate the real substrate and thus confer a better clinical outcome.

Study limitations

Atrial cardiac GP are reported to contain three types of neurons - efferent sympathetic, efferent parasympathetic and afferent ones.33 These neurons might co-localize with each other. Our recording methods could not differentiate one type of nerve activity from the other. A second limitation is that we only recorded from the left stellate ganglion. The relationship between right stellate ganglion and ICNA was not determined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lei Lin, Jian Tan, Erica Forster and Stephanie Plummer for their assistance.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by NIH Grants P01 HL78931, R01 HL78932, 71140, a Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2008-357-E00028) funded by the Korean Government (EC), an AHA Established Investigator Award (SFL) and a Medtronic-Zipes Endowments (PSC).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Dr Xiaohong Zhou of Medtronic Inc. donated equipment used in these studies.

References

- 1.Marshall J. On the development of the great anterior veins in man and mammalia: including an account of certain remnants of foetal structure found in the adult, a comparative view of these great veins in the different mammalia, and an analysis of their occasional peculiarities in the human subject. Phil Trans R Soc Lond. 1850;140:133–169. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherlag BJ, Yeh BK, Robinson MJ. Inferior interatrial pathway in the dog. Circulation Research. 1972;31:18–35. doi: 10.1161/01.res.31.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doshi RN, Wu TJ, Yashima M, Kim YH, Ong JJC, Cao JM, Hwang C, Yashar P, Fishbein MC, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS. Relation between ligament of Marshall and adrenergic atrial tachyarrhythmia. Circulation. 1999;100:876–883. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.8.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armour JA, Richer LP, Page P, Vinet A, Kus T, Vermeulen M, Nadeau R, Cardinal R. Origin and pharmacological response of atrial tachyarrhythmias induced by activation of mediastinal nerves in canines. Auton Neurosci. 2005;118:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulphani JS, Arora R, Cain JH, Villuendas R, Shen S, Gordon D, Inderyas F, Harvey LA, Morris A, Goldberger JJ, Kadish AH. The ligament of Marshall as a parasympathetic conduit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1629–H1635. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00139.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang C, Wu TJ, Doshi RN, Peter CT, Chen PS. Vein of Marshall cannulation for the analysis of electrical activity in patients with focal atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2000;101:1503–1505. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.13.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katritsis D, Ioannidis JP, Anagnostopoulos CE, Sarris GE, Giazitzoglou E, Korovesis S, Camm AJ. Identification and catheter ablation of extracardiac and intracardiac components of ligament of Marshall tissue for treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2001;12:750–758. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung BC, Dave AS, Tan AY, Gholmieh G, Zhou S, wang DC, Akingba G, Fishbein GA, Montemagno C, Lin SF, Chen LS, Chen PS. Circadian variations of stellate ganglion nerve activity in ambulatory dogs. Heart Rhythm. 2005;3:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogawa M, Zhou S, Tan AY, Song J, Gholmieh G, Fishbein MCLH, Siegel RJ, Karagueuzian HS, Chen LS, in SF, Chen PS. Left stellate ganglion and vagal nerve activity and cardiac arrhythmias in ambulatory dogs with pacing-induced congestive heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan AY, Zhou S, Ogawa M, Song J, Chu M, Li H, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Chen LS, Chen PS. Neural mechanisms of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia in ambulatory canines. Circulation. 2008;118:916–925. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armour JA, Murphy DA, Yuan BX, Macdonald S, Hopkins DA. Gross and microscopic anatomy of the human intrinsic cardiac nervous system. Anat Rec. 1997;247:289–298. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199702)247:2<289::AID-AR15>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swissa M, Zhou S, Paz O, Fishbein MC, Chen LS, Chen PS. A Canine Model of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation and Paroxysmal Atrial Tachycardia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1851–H1857. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00083.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benitez D, Gaydecki PA, Zaidi A, Fitzpatrick AP. The use of the Hilbert transform in ECG signal analysis. Comput Biol Med. 2001;31:399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0010-4825(01)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nademanee K, McKenzie J, Kosar E, Schwab M, Sunsaneewitayakul B, Vasavakul T, Khunnawat C, Ngarmukos T. A new approach for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: mapping of the electrophysiologic substrate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2044–2053. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao JM, Chen LS, KenKnight BH, Ohara T, Lee MH, Tsai J, Lai WW, Karagueuzian HS, Wolf PL, Fishbein MC, Chen PS. Nerve sprouting and sudden cardiac death. Circulation Research. 2000;86:816–821. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makino M, Inoue S, Matsuyama TA, Ogawa G, Sakai T, Kobayashi Y, Katagiri T, Ota H. Diverse myocardial extension and autonomic innervation on ligament of Marshall in humans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:594–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson W, Tong YL, Lee JK, Halberg F. Methods for cosinor-rhythmometry. Chronobiologia. 1979;6:305–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan BX, Ardell JL, Hopkins DA, Losier AM, Armour JA. Gross and microscopic anatomy of the canine intrinsic cardiac nervous system. Anat Rec. 1994;239:75–87. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092390109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armour JA. Potential clinical relevance of the ‘little brain’ on the mammalian heart. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:165–176. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou Y, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Zhang Y, Lu Z, Truong K, Patterson E, Lazzara R, Jackman WM, Po SS. Ganglionated plexi modulate extrinsic cardiac autonomic nerve input: effects on sinus rate, atrioventricular conduction, refractoriness, and inducibility of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu G, Scherlag BJ, Lu Z, Ghias M, Zhang Y, Patterson E, Dasari TW, Zacharias S, Lazzara R, Jackman WM, Po SS. An acute experimental model demonstrating 2 different forms of sustained atrial tachyarrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:384–392. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.810689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou CC, Zhou S, Tan AY, Hayashi H, Nihei M, Chen PS. High Density Mapping of Pulmonary Veins and Left Atrium During Ibutilide Administration in a Canine Model of Sustained Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2704–2713. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00537.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayachandran JV, Sih HJ, Winkle W, Zipes DP, Hutchins GD, Olgin JE. Atrial fibrillation produced by prolonged rapid atrial pacing is associated with heterogeneous changes in atrial sympathetic innervation. Circulation. 2000;101:1185–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.10.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang CM, Wu TJ, Zhou SM, Doshi RN, Lee MH, Ohara T, Fishbein MC, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS, Chen LS. Nerve sprouting and sympathetic hyperinnervation in a canine model of atrial fibrillation produced by prolonged right atrial pacing. Circulation. 2001;103:22–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Z, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Niu G, Fung KM, Zhao L, Ghias M, Jackman WM, Lazzara R, Jiang H, Po SS. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation: autonomic mechanism for atrial electrical remodeling induced by short-term rapid atrial pacing. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:184–192. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.784272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armour JA, Hageman GR, Randall WC. Arrhythmias induced by local cardiac nerve stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1972;223:1068–1075. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.223.5.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin J, Scherlag BJ, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Liu S, Patterson E, Jackman WM, Lazzara R, Po SS. Inducibility of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias along the ligament of marshall: role of autonomic factors. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:955–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin J, Scherlag BJ, Niu G, Lu Z, Patterson E, Liu S, Lazzara R, Jackman WM, Po SS. Autonomic elements within the ligament of Marshall and inferior left ganglionated plexus mediate functions of the atrial neural network. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armour JA, Hopkins DA. Activity of canine in situ left atrial ganglion neurons. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H1207–H1215. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.4.H1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu Z, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Niu G, Ghias M, Jackman WM, Lazzara R, Jiang H, Po SS. Autonomic mechanism for complex fractionated atrial electrograms: evidence by fast fourier transform analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:835–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lellouche N, Buch E, Celigoj A, Siegerman C, Cesario D, De DC, Mahajan A, Boyle NG, Wiener I, Garfinkel A, Shivkumar K. Functional characterization of atrial electrograms in sinus rhythm delineates sites of parasympathetic innervation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50:1324–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pokushalov E, Romanov A, Shugayev P, Artyomenko S, Shirokova N, Turov A, Katritsis DG. Selective ganglionated plexi ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butler CK, Smith FM, Cardinal R, Murphy DA, Hopkins DA, Armour JA. Cardiac responses to electrical stimulation of discrete loci in canine atrial and ventricular ganglionated plexi. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;259:H1365–H1373. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.5.H1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.