Abstract

Purpose

To comparatively analyze treatment-related adverse events and the treatment dropout rate between immunochemotherapy and target therapy in Korea.

Materials and Methods

Forty-nine subjects with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (21 target therapy recipients and 28 immunochemotherapy recipients) who underwent either 6-week cycles of sunitinib treatment (50 mg once daily for 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off) or 8-week cycles of immunochemotherapy (combination of interleukin [IL]-2, interferon [IFN]-alpha, and 5-fluorouracil [FU]) were enrolled. Treatment-related toxicity was objectively graded and quantitative analysis was performed with a scoring system. Patient compliance was categorized into three classes (1: administration as scheduled, 2: dose modification required, 3: discontinuation required).

Results

Compared with those of the immunochemotherapy group, subjects of the sunitinib-treatment group had higher occurrence rates of mucositis-stomatitis (43% vs. 10%), hand-foot syndrome (38% vs. 0%), diarrhea (33% vs. 14%), and hypertension (33% vs. 14%). According to the toxicity-grade-based scoring system, the total incidence and severity of toxicities were not significantly different between the two groups (p>0.05), whereas high-grade hematologic toxicities were more frequent in the immunochemotherapy group. The dropout rate of the immunochemotherapy group was significantly higher than that of the sunitinib group (administration as scheduled: 52% vs. 21%, p=0.026; discontinuation required: 19% vs. 50%, p=0.037).

Conclusions

The results of this study are indicative of a comparable treatment-related toxicity profile of sunitinib and greater adherence to the treatment protocol in comparison with immunochemotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC).

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Sunitinib, Toxicity

INTRODUCTION

Due to the more widespread practice of regular health examinations and advancements in diagnostic imaging technology, the rate of diagnosis of asymptomatic, early stage renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has been increasing [1]. However, owing to the absence of characteristic symptoms, metastases are observed in 30% of initial diagnoses, and even in cases diagnosed with localized RCC and in which nephrectomy with curative intent is carried out, a recurrence/metastasis rate of 20-40% is observed during follow-up [2]. Consequently, most patients with RCC require systemic therapy; however, metastatic RCC (mRCC) shows an extremely poor response to conventional therapeutic strategies such as chemotherapy, curative radiation therapy, and hormone therapy, and the prognosis is reported to be very poor, with a mean survival period of 12 months and a 2-year survival rate of 10-20%. As a result, until recently, the only effective treatment of metastatic disease was cytokine-based immunotherapy with interferon (IFN)-alpha and interleukin (IL)-2, which unfortunately produces only relatively low objective response rates of 10-20%. In addition, among other problems, severe systemic toxicities have been observed at therapeutic doses, in some cases requiring inpatient treatment including admission into intensive care units, but no suitable replacement has been available to date [2].

Recent advances in our understanding of the biology and genetics of RCC have led to the emergence of novel molecular targeted approaches for the treatment of mRCC. Sunitinib malate is the current first-line targeted therapeutic agent for favorable and intermediate-risk groups with mRCC [3]. Toxicities observed at therapeutic doses are associated with a distinct pattern of adverse events in mRCC, which are different from those observed with conventional chemotherapy or immunotherapy [4,5]. As such, it is important for physicians treating mRCC patients with targeted agents to be aware of potential treatment-related adverse events and to initiate management strategies promptly to avoid deleterious effects on the clinical outcome and patient's quality of life. However, few studies have been published to date in Korea regarding the clinical efficacy and treatment-related toxicities of sunitinib [6]. Although studies overseas have reported the treatment-related toxicities to be relatively mild, clinical experience has shown the adverse effects to be quite significant.

In light of this situation, we carried out a comparative analysis of treatment-related adverse events and the dropout rate in Korean patients who have undergone treatment with either sunitinib, currently the first-line therapeutic agent for mRCC, or IL-2- or INF-alpha-based immunochemotherapy, the mainstay over the past 20 years [7].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Subjects

The total subject pool consisted of 49 patients who were diagnosed with mRCC between January 2000 and June 2009, whereas patients in the sunitinib group were enrolled since 2006. Of the 49 patients, 46 (94%) were diagnosed with clear cell RCC. Of these subjects, we enrolled 28 patients who had undergone an 8-week combination immunochemotherapy regimen based on IFN-alpha, IL-2, and 5-fluorouracil (FU), and 21 patients who had undergone target therapy involving sunitinib treatment cycles consisting of 4 weeks' administration of sunitinib at a dose of 50 mg/day followed by a 2-week break.

2. Investigation method

1) Treatment protocol

Combination immunochemotherapy was carried out through subcutaneous administration of a combination of recombinant IL-2 and IFN-alpha-2a and intravenous fluorouracil according to the schedule proposed by Atzpodien et al [8]. The regimen consisted of recombinant human IL-2 (given subcutaneously at 20 MU/m2 on days 3-5 of weeks 1 and 4 and at 5 MIU/m2 on days 1, 3, and 5 of weeks 2 and 3), recombinant human INF-alpha (given subcutaneously at 6 MIU/m2 on day 1 of weeks 1 and 4 and on days 1, 3, and 5 of weeks 2 and 3 and at 9 MIU/m2 on days 1, 3, and 5 of weeks 5-8), and 5-fluorouracil (given intravenously at 750 mg/m2 once weekly during weeks 5-8).

Through meticulous history-taking before the start of treatment, patients with an The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 2 or higher or who were aged less than 18 years or greater than 75 years were excluded, as were patients with a past history of heart disease; those with major organ dysfunctions or central nervous system metastases; those with a history of seizure disorders, autoimmune disorders, or organ transplants; and those who were currently undergoing administration of corticosteroids or immunosuppressives. Sunitinib treatment was carried out in 6-week cycles, each consisting of daily sunitinib administration at a dose of 50 mg over a period of 4 weeks followed by a resting period of 2 weeks. If insufficient improvement in the general condition was seen during the resting period, or if high-grade adverse effects were observed, therapy was temporarily halted until either complete recovery or alleviation to lower-grade adverse events was achieved.

2) Follow-up

For a full assessment of the patient's risk, meticulous history taking, physical examination, routine blood tests, abdominal CT, radionuclide bone scan, simple chest radiographs, and electrocardiogram (EKG) examination were carried out within 4 weeks of the start of therapy. In addition, thyroid function tests and echocardiography were mandatory in patients scheduled to receive targeted therapy. Therapeutic response was assessed at the end of each cycle in the case of immunochemotherapy; as for target therapy, response was evaluated at the end of each 4-week medication phase during the first four cycles and at the end of every two cycles thereafter.

3) Assessment of response

Assessment of response was based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor (RECIST); the sum of the longest unidirectional diameters of all measurable lesions was evaluated. Complete resolution of all measurable lesions and no appearance of new lesions for at least 4 weeks was considered as a complete response. Reduction by 30% or more was considered as a partial response, whereas reduction by less than 30% or an increase by less than 20% was considered as stable. An increase by 20% or more or the appearance of new lesions was considered as progressive [9].

4) Assessment of toxicity

Assessment of therapy-related toxicities was based on National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version; the observed adverse effects were classified as either hematologic or nonhematologic and were graded from 1 to 4 depending on the severity. In addition, in order to make a comparative analysis of the prevalence and severity of each adverse event, an objective and quantitative analysis was carried out in the present study by using a scoring system involving assignment of a score ranging from 1 to 4 points depending on the grade (1 point for grade 1 and 4 points for grade 4) and summation of the scores.

5) Assessment of the dropout rate

In order to objectively evaluate the therapy-related dropout rate, the subjects were divided into 3 groups: a group in which treatment was carried out per the aforementioned protocols (Group 1: as scheduled), a group in which a reduction in dosage or temporary cessation was required before treatment could resume (Group 2: dose modification required), and a group in which significant adverse effects, refusal of the treatment by the patient, or progression of disease necessitated complete cessation of treatment or follow-up became unfeasible (Group 3: dosage discontinuation required). In general, upon occurrence of grade 3 hematologic toxicities, treatment was halted until the severity was lessened to grade 2 or below or until the patient recovered to the pretherapeutic state, at which time treatment was resumed at the same dose. Upon occurrence of grade 4 hematologic toxicities or nonhematologic toxicities of grade 3 or 4, treatment was ceased until the severity was lessened to grade 2 or 1, respectively, and a decrement in the dose was made upon resumption of treatment.

6) Statistical analysis

The statistical endpoints in our analysis were (1) the incidence and severity of treatment-related adverse events, (2) the dropout rate, and (3) the objective response rate. Statistical analysis was carried out by using SPSS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Analysis of continuous variables was made by using Student's t-test, and categorical variables were analyzed by using the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. p-values less than 0.05 were considered to represent statistical significance.

RESULTS

1. Subject population

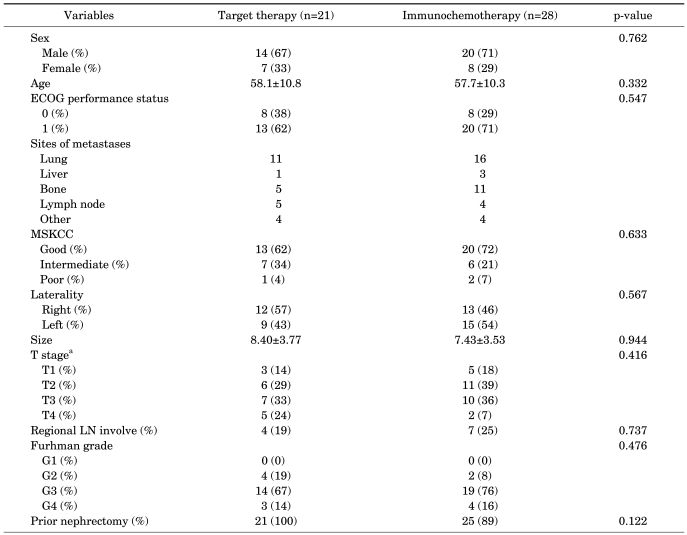

The clinical features of the immunochemotherapy group and of the target therapy group are as shown in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of age, gender, ECOG performance status, size of tumor, histologic grade, nephrectomy status, involvement of adjacent lymph nodes, number of metastatic lesions, or time after diagnosis of metastasis at which systemic treatment was commenced (p>0.05).

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

ECOG: The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, MSKCC: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center risk classification , LN: lymph node, a: pathologically proved T stage except 3 patients in immunochemotherapy group who did not underwent nephrectomy

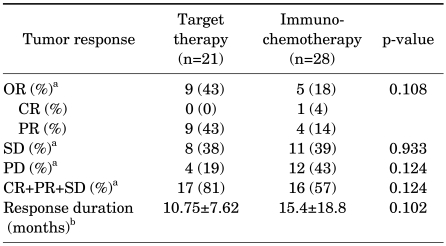

2. Objective response rate and duration of response

The median number of cycles and follow-up period of the immunochemotherapy and target therapy group were 2 cycles (range, 1-5 cycles), 4 cycles (range, 1-11 cycles), 23.5 months, and 22 months. The objective treatment response rate was 18% for the immunochemotherapy group and 43% for the target therapy group; the response rate was higher for target therapy, but this difference lacked statistical significance (p=0.108). In addition, the nonprogression rate (including cases with stable disease) did not differ significantly between the two groups. For subjects who showed therapeutic response, the average duration of response was 15.4 months (range, 4-48 months) for the immunochemotherapy group and 10.7 months (range, 7-14 months) for the target therapy group (p=0.102) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Objective tumor response of target therapy and immunochemotherapy

OR: objective response, CR: complete response, PR: partial response, SD: stable disease, PD: progressive disease, a: chi-square test, b: Student's t-test

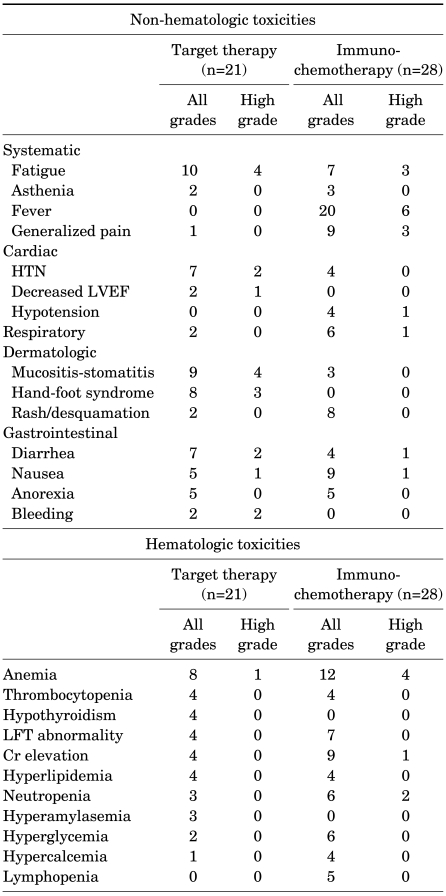

3. Therapy-related adverse effects

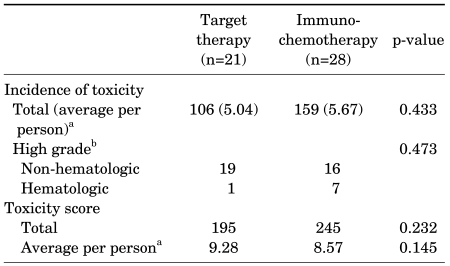

Among subjects who underwent immunochemotherapy, the most frequently encountered nonhematologic toxicities were flu-like symptoms, including acute-onset fever occurring within 6 hours of agent administration (71%), fatigue (25%), and generalized aches such as muscular pain (32%). In addition, 13 cases (46%) of pulmonary edema or hypotension thought to be caused by vascular leak were observed [10]; of these, one exhibited high-grade dyspnea and pleural effusion necessitating oxygen administration and thoracentesis. On the other hand, the most frequently encountered nonhematologic toxicities in the target therapy group were fatigue (47%), hypertension (33%), and diarrhea (33%). Particularly higher compared with that in the immunochemotherapy subjects was the incidence of dermatologic adverse events, including mucositis-stomatitis (43%) and hand-foot syndrome (38%). High-grade occurrences severe enough to impede daily life activities were also observed in 4 of 9 (44%) and 3 of 8 (37%) cases, respectively (Table 3). In addition, reversible symptomatic congestive heart failure was observed in one subject, resulting in permanent cessation of treatment, and two subjects experienced temporary cessation of treatment due to high-grade upper gastrointestinal bleeding requiring emergency endoscopic intervention (Table 3). Hematologic toxicities associated with immunochemotherapy included anemia (43%), neutropenia (21%), and thrombocytopenia (14%); high-grade anemia was observed in 4 cases, and severe thrombocytopenia was observed in 1 case. However, although hematologic toxicities associated with target therapy included anemia (38%) and neutropenia (14%), none of the cases involved high-grade toxicities except one case of high-grade anemia (Table 3). Quantitative analysis of treatment-related adverse events using the scoring system showed comparable overall incidences and severity of treatment-related toxicity (p>0.05) (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Nonhematologic and hematologic toxicity profile of target therapy and immunochemotherapy

HTN: hypertension, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, LFT: liver function test, Cr: creatinine

TABLE 4.

Treatment-related toxicity profile (hematologic and nonhematologic)

a: Student's t-test, b: chi-square test

4. Dropout rate

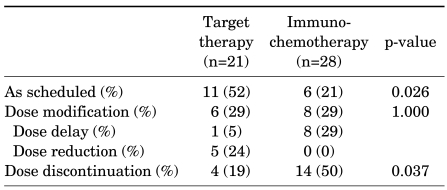

In the immunochemotherapy group, 6 (21%) subjects underwent treatment as scheduled, and 8 (29%) experienced temporary cessation of treatment due to adverse effects (4 due to general weakness, 2 due to renal function abnormality, 1 due to high-grade fever, and 1 due to high-grade anemia). But none required dosage reduction. In addition, treatment was completely ceased in 14 subjects (50%); causes included disease progression in 10 cases, severe generalized weakness in 2 cases, generalized seizure in 1 case, and patient refusal in 1 case. On the other hand, in the sunitinib therapy group, 11 (52%) subjects underwent treatment as scheduled. One case involved a 2-week delay in treatment due to a reversible abnormality in cardiac wall movement on echocardiography, and 5 subjects (24%) underwent gradual dose reduction due to therapy-related high-grade toxicities, consisting of mucositis-stomatitis, hand-foot syndrome, and diarrhea. Furthermore, complete cessation of sunitinib treatment was observed in 4 cases (19%) as the result of disease progression, symptomatic congestive heart failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, and death.

The dropout rate was lower in the target therapy subjects than in the immunochemotherapy patients (52% vs. 21%; p=0.026), and fewer cases of complete treatment cessation occurred in the target therapy group (19% vs. 50%, respectively; p=0.037) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Treatment-related dropout rate of the patients

DISCUSSION

Treatment of advanced RCC has recently undergone a major change with the development of novel molecular targeted agents and potent angiogenesis inhibitors. Sunitinib is an orally administered, low-molecular-weight inhibitor of multiple receptor kinases. The antitumor effect of sunitinib is mediated through interference with platelet-derived growth factor receptor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor [11]. In the two phase II open trials in patients with mRCC refractory to immunotherapy, unexpected and significant improvements in the response rate and overall survival with partial response were seen in 40-44% of patients; the median progression-free survival was 8.7 months, and the disease-specific survival was 16.4 months [5,12]. On the basis of these promising data, a subsequent large-scale randomized phase III clinical trial comparing the relative efficacies of sunitinib and IFN-2a showed the former to be superior in terms of objective response rate to treatment (31% vs. 6%), median progression-free survival (11 months vs. 5 months), and overall survival (26.4 months vs. 21.8 months) in all prognosis groups as classified according to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center criteria [13]. Supported by such superior clinical results, sunitinib is currently used as the drug of choice in the treatment of mRCC [14]; nevertheless, due to significant therapy-related adverse events, reductions in dosage, postponements in treatment schedules, and ultimately complete cessation of treatment are common in actual clinical usage, despite the excellent rate of response to treatment [15-17].

In previous studies, immunotherapy and targeted molecular therapy were shown to differ in their treatment-related toxicities as a result of the different mechanisms responsible for their antitumor activities. Adverse events associated with immunotherapy largely consist of those due to cytokines released by activated T lymphocytes and natural killer cells, such as fever, myalgia, and general malaise, among other systemic symptoms, and those due to increased vascular wall permeability, including generalized and pulmonary edema and hypotension. The more frequently encountered toxicities associated with target therapy include hypertension, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, hemorrhage, dermatological symptoms, and diarrhea. Likewise, in the present study, systemic constitutional symptoms such as fever, chill, and general malaise and pulmonary symptoms were the more frequently encountered nonhematologic adverse effects in the immunochemotherapy subjects. On the other hand, symptoms such as hypertension, hand-foot syndrome, mucositis-stomatitis, diarrhea, and nausea were more frequently observed in the sunitinib therapy group, similar to the results of previous studies. In addition, although hematologic toxicities were observed in both groups, the incidence was relatively lower compared with the results of other studies, and in most cases, the toxicities were of lower grades not requiring any special intervention.

Furthermore, whereas some studies have reported incidence rates as high as 85% for thyroid function test anomalies in patients receiving sunitinib treatment, the incidence rate observed in the present study was considerably lower at 27% [18]. A decrease in the left ventricular ejection fraction is a rare but potentially threatening complication. Chu et al reported that the incidence rate of cardiovascular toxicity associated with sunitinib treatment was 21% [19]; the figure obtained in the present study did not differ much at 13%, and most of the patients with newly developed treatment-related hypertension were successfully managed by commencement of standard antihypertensive drugs without any demonstrable vascular event. In patients already receiving medical therapy for hypertension, blood pressure was also adequately controlled with dose escalation of the currently prescribed antihypertensive medication. However, one of these subjects developed symptomatic congestive heart failure with a more than 20% decrease in the left ventricular ejection fraction from baseline; the subject's cardiac function returned to the pretherapeutic level subsequent to cessation of treatment.

Furthermore, in the present study, although an impressive superior objective response rate was observed in targeted therapy subjects, approximately 60% of the patients with mRCC did not respond to sunitinib. Response duration in sunitinib therapy subjects was relatively shorter than in the immunochemotherapy subjects, although without statistical significance, probably because of the limited number of patients. Complete remission was not seen, although long-term complete remission spanning 6 years was observed in one subject who received immunochemotherapy; this finding is similar to those of previously published studies. These results can be explained by tumor cell adaptation and compensation with overexpression of nontargeted oncogenic growth factor or receptor tyrosine kinase that confer resistance to the tumor cell.

In a study assessing satisfaction with treatment in patients receiving sunitinib or IFN-alpha treatment by use of self-filled questionnaires, Cella et al stated that at all stages, the physical, functional, psychological, and social satisfaction was greater in patients receiving sunitinib treatment [20]. Similarly, in this study, although the overall incidence of therapy-related adverse events and high-grade nonhematologic toxicities was higher for targeted therapy, most of the adverse events were low-grade, manageable toxicities, and potentially lethal high-grade toxicities were relatively less common. Even when toxicities did occur, they were usually resolved during the 2-week break at the end of each cycle. These off-dosage periods, along with the greater convenience of sunitinib because of its once daily oral dosing on an outpatient basis and the possibility of toxicity prevention through stepwise dose reduction, accounted for the greater patient compliance in the target therapy subjects.

One limitation of the present study is that it rests on retrospective examination of medical reports. Although a relatively accurate assessment of therapeutic toxicities, based on clinicians' observations and review of systems charts, was possible for the most part, some reliance on the limited recollections of the subjects was still present. Furthermore, because CTCAE, which was used in evaluating nonhematological adverse effects, uses the impact on daily life activities as the criterion in differentiating between low-grade and high-grade toxicities, an embedded limitation in the objectivity of assessing the severity of toxicities was present. In addition, identifying whether a particular symptom bore direct association to the systemic treatment of metastatic renal carcinoma or whether it occurred as part of the natural course of the disease or another co-morbidity was impossible in reality.

CONCLUSIONS

Sunitinib, which is currently used as the first-line treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, was shown to be superior to immunochemotherapy in terms of objective therapeutic response and also demonstrated acceptable tolerability. The adverse events with sunitinib were predictable, relatively less severe, and stereotypical in general, and the dropout rate with sunitinib was relatively lower than that for immunotherapy in Korea.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Kyung Hee University 2006 (KHU-20060477).

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Jayson M, Sanders H. Increased incidence of serendipitously discovered renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 1998;51:203–205. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Russo P. Systemic therapy for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2000;163:408–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann E, Bierer S, Wülfing C. Update on systemic therapies of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol. 2010;28:303–309. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0519-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kollmannsberger C, Soulierers D, Wong R, Scalera A, Gaspo R, Bjarnason G. Sunitinib therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: recommendations for management of side effects. Can Urol Assoc J. 2007;1(2 Suppl):S41–S54. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, Hudes GR, Wilding G, Figlin RA, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong MH, Kim HS, Kim C, Ahn JR, Chon HJ, Shin SJ, et al. Treatment outcome of sunitinib treatment in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients: a single cancer center experience in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2009;41:67–72. doi: 10.4143/crt.2009.41.2.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song CR, Ahn HJ, Kim CS. Factors modulating response to immunonchemotherapy in advanced renal cell carcinomas. Korean J Urol. 2002;43:913–918. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atzpodien J, Kirchner H, Duensing S, Lopez Hanninen E, Franzke A, Buer J, et al. Biochemotherapy of advanced metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: results of the combination of interleukin-2, alpha-interferon, 5-fluorouracil, vinblastine and 13-cis-retinoic acid. World J Urol. 1995;13:174–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00184875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baluna R, Vitetta ES. Vascular leak syndrome: a side effect of immunotherapy. Immunopharmacology. 1997;37:117–132. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(97)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams VR, Leggas M. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma and gastrointestinal tumors. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1338–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Rosenberg J, Bukowski RM, Curti BD, George DJ, et al. Sunitinib efficacy against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;178:1883–1887. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alpha in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motzer RJ, Bukowski RM. Targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5601–5608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutson TE, Figlin RA, Kuhn JG, Motzer RJ. Targeted therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an overview of toxicity and dosing strategies. Oncologist. 2008;13:1084–1096. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Veldt AA, Boven E, Helgason HH, van Wouwe M, Berkhof J, de Gast G, et al. Predictive factors for severe toxicity of sunitinib in unselected patients with advanced renal cell cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:259–265. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhojani N, Jeldres C, Patard JJ, Perrotte P, Suardi N, Hutterer G, et al. Toxicities associated with the administration of sorafenib, sunitinib, and temsirolimus and their management in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2008;53:917–930. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rini BI, Tamaskar I, Shaheen P, Salas R, Garcia J, Wood L, et al. Hypothyroidism in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:81–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu TF, Rupnick MA, Kerkela R, Dallabrida SM, Zurakowski D, Nguyen L, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet. 2007;370:2011–2019. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61865-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cella D, Li JZ, Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin A, Charbonneau C, Kim ST, et al. Quality of life in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib or interferon alpha: results from a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3763–3769. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]