Abstract

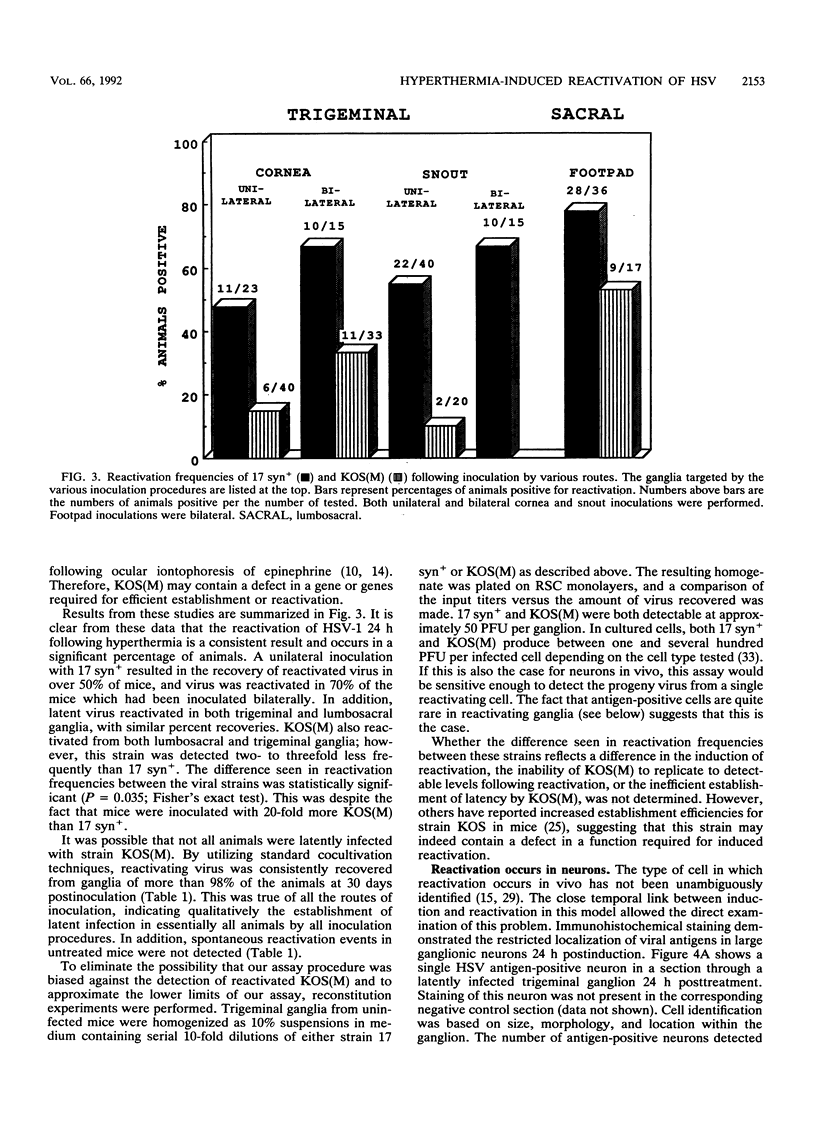

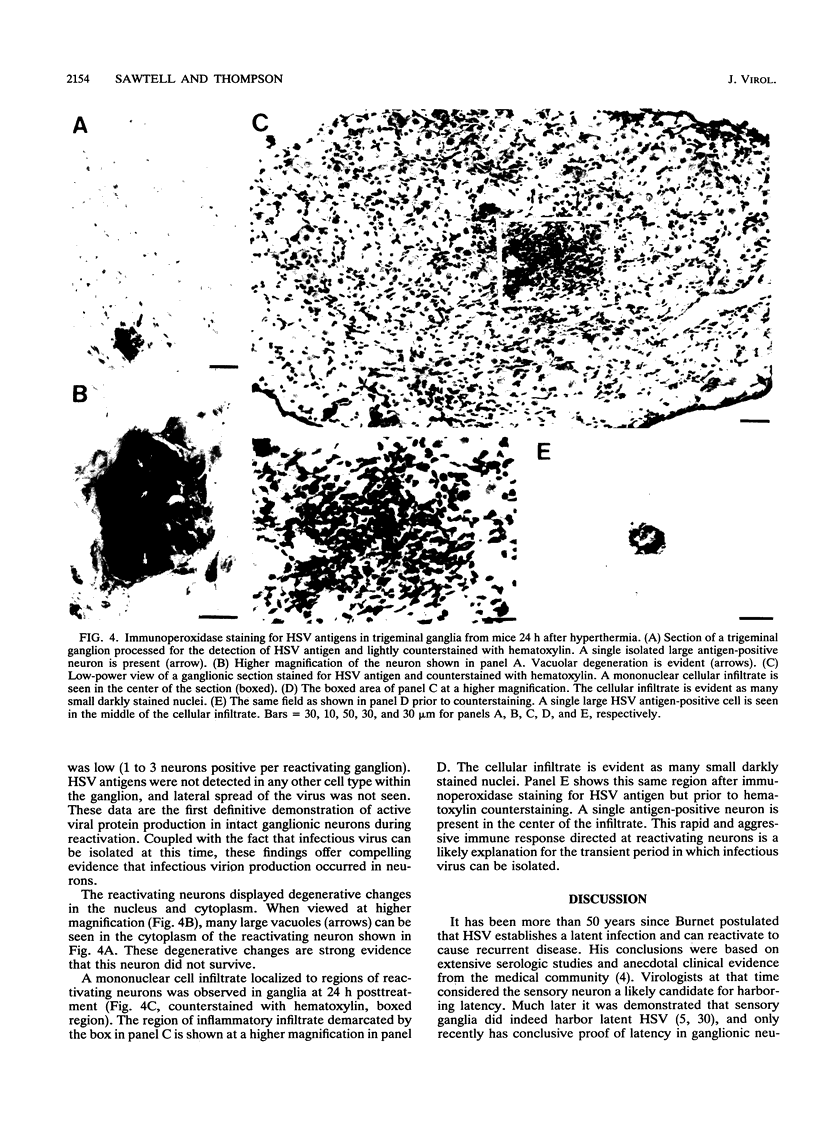

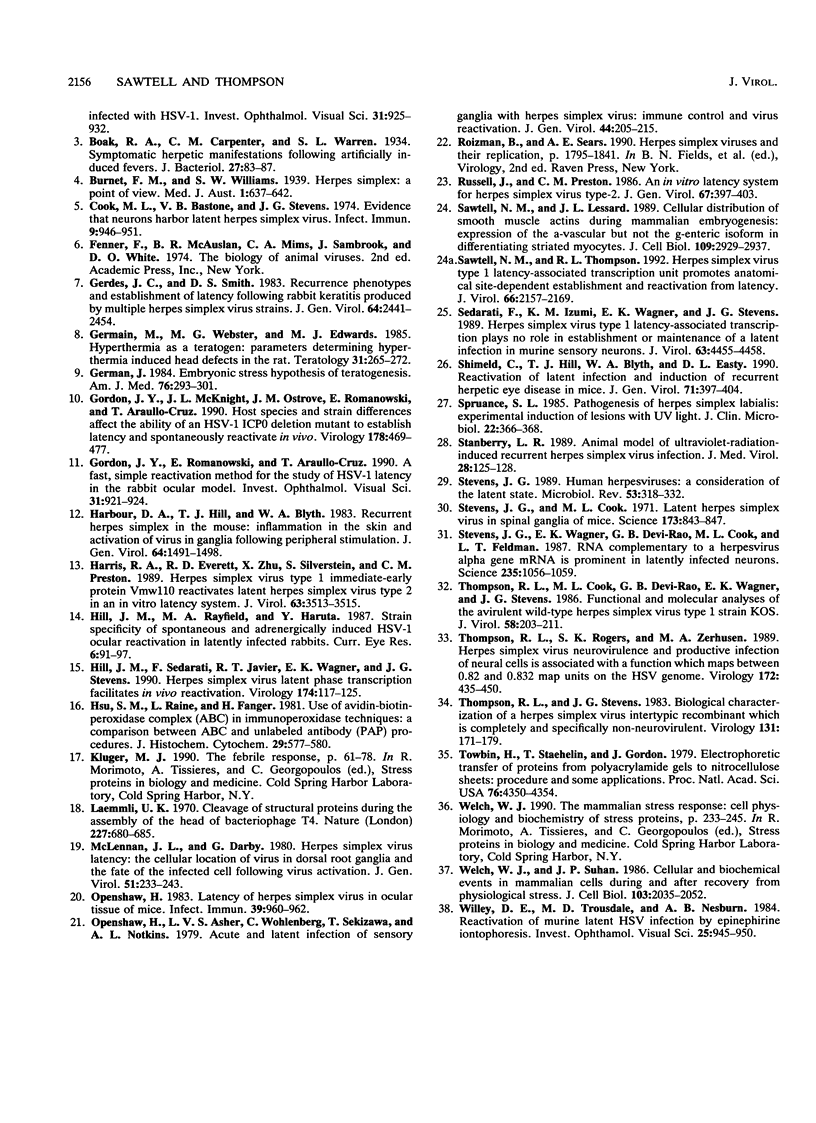

A rapid and physiologically relevant hyperthermia-based induction procedure has been utilized to develop an in vivo model of induced herpes simplex virus (HSV) reactivation in outbred Swiss Webster mice. This procedure was found to efficiently reactivate latent virus from both trigeminal and lumbosacral ganglia. Examination of the time between hyperthermia and virus production demonstrated that detectable levels of infectious virus were present in ganglia as soon as 14 h posttreatment, with peak percent recoveries at 24 h. These data indicated that the switch from latent to active viral gene transcription occurred rapidly following treatment. Immunohistochemical staining for HSV type 1 antigens revealed rare antigen-positive ganglionic neurons 24 h postinduction. HSV antigens were not detected in any other cell type, and lateral spread of the infection was not observed. This is the first report of the detection of HSV antigens in vivo following induced reactivation in the intact nervous system and demonstrates that the neuron is the site of infectious virus production. In addition, our data strongly suggest that at least some neurons in which HSV antigens are detected during reactivation do not survive. Because the temporal and spatial characteristics of HSV reactivation have been clearly defined, this model is uniquely suited for the molecular dissection of the reactivation process.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beyer C. F., Hill J. M., Reidy J. J., Beuerman R. W. Corneal nerve disruption reactivates virus in rabbits latently infected with HSV-1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990 May;31(5):925–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook M. L., Bastone V. B., Stevens J. G. Evidence that neurons harbor latent herpes simplex virus. Infect Immun. 1974 May;9(5):946–951. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.5.946-951.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J. C., Smith D. S. Recurrence phenotypes and establishment of latency following rabbit keratitis produced by multiple herpes simplex virus strains. J Gen Virol. 1983 Nov;64(Pt 11):2441–2454. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-11-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain M. A., Webster W. S., Edwards M. J. Hyperthermia as a teratogen: parameters determining hyperthermia-induced head defects in the rat. Teratology. 1985 Apr;31(2):265–272. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420310212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German J. Embryonic stress hypothesis of teratogenesis. Am J Med. 1984 Feb;76(2):293–301. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90788-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Y. J., McKnight J. L., Ostrove J. M., Romanowski E., Araullo-Cruz T. Host species and strain differences affect the ability of an HSV-1 ICP0 deletion mutant to establish latency and spontaneously reactivate in vivo. Virology. 1990 Oct;178(2):469–477. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90344-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Y. J., Romanowski E., Araullo-Cruz T. A fast, simple reactivation method for the study of HSV-1 latency in the rabbit ocular model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990 May;31(5):921–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour D. A., Hill T. J., Blyth W. A. Recurrent herpes simplex in the mouse: inflammation in the skin and activation of virus in the ganglia following peripheral stimulation. J Gen Virol. 1983 Jul;64(Pt 7):1491–1498. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-7-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. A., Everett R. D., Zhu X. X., Silverstein S., Preston C. M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein Vmw110 reactivates latent herpes simplex virus type 2 in an in vitro latency system. J Virol. 1989 Aug;63(8):3513–3515. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.8.3513-3515.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. M., Rayfield M. A., Haruta Y. Strain specificity of spontaneous and adrenergically induced HSV-1 ocular reactivation in latently infected rabbits. Curr Eye Res. 1987 Jan;6(1):91–97. doi: 10.3109/02713688709020074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. M., Sedarati F., Javier R. T., Wagner E. K., Stevens J. G. Herpes simplex virus latent phase transcription facilitates in vivo reactivation. Virology. 1990 Jan;174(1):117–125. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S. M., Raine L., Fanger H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981 Apr;29(4):577–580. doi: 10.1177/29.4.6166661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan J. L., Darby G. Herpes simplex virus latency: the cellular location of virus in dorsal root ganglia and the fate of the infected cell following virus activation. J Gen Virol. 1980 Dec;51(Pt 2):233–243. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-2-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw H., Asher L. V., Wohlenberg C., Sekizawa T., Notkins A. L. Acute and latent infection of sensory ganglia with herpes simplex virus: immune control and virus reactivation. J Gen Virol. 1979 Jul;44(1):205–215. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-44-1-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw H. Latency of herpes simplex virus in ocular tissue of mice. Infect Immun. 1983 Feb;39(2):960–962. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.960-962.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J., Preston C. M. An in vitro latency system for herpes simplex virus type 2. J Gen Virol. 1986 Feb;67(Pt 2):397–403. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-2-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawtell N. M., Lessard J. L. Cellular distribution of smooth muscle actins during mammalian embryogenesis: expression of the alpha-vascular but not the gamma-enteric isoform in differentiating striated myocytes. J Cell Biol. 1989 Dec;109(6 Pt 1):2929–2937. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawtell N. M., Thompson R. L. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcription unit promotes anatomical site-dependent establishment and reactivation from latency. J Virol. 1992 Apr;66(4):2157–2169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2157-2169.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedarati F., Izumi K. M., Wagner E. K., Stevens J. G. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcription plays no role in establishment or maintenance of a latent infection in murine sensory neurons. J Virol. 1989 Oct;63(10):4455–4458. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4455-4458.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimeld C., Hill T. J., Blyth W. A., Easty D. L. Reactivation of latent infection and induction of recurrent herpetic eye disease in mice. J Gen Virol. 1990 Feb;71(Pt 2):397–404. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-2-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruance S. L. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex labialis: experimental induction of lesions with UV light. J Clin Microbiol. 1985 Sep;22(3):366–368. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.3.366-368.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanberry L. R. Animal model of ultraviolet-radiation-induced recurrent herpes simplex virus infection. J Med Virol. 1989 Jul;28(3):125–128. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. G., Cook M. L. Latent herpes simplex virus in spinal ganglia of mice. Science. 1971 Aug 27;173(3999):843–845. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3999.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. G. Human herpesviruses: a consideration of the latent state. Microbiol Rev. 1989 Sep;53(3):318–332. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.3.318-332.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. G., Wagner E. K., Devi-Rao G. B., Cook M. L., Feldman L. T. RNA complementary to a herpesvirus alpha gene mRNA is prominent in latently infected neurons. Science. 1987 Feb 27;235(4792):1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.2434993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. L., Cook M. L., Devi-Rao G. B., Wagner E. K., Stevens J. G. Functional and molecular analyses of the avirulent wild-type herpes simplex virus type 1 strain KOS. J Virol. 1986 Apr;58(1):203–211. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.1.203-211.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. L., Rogers S. K., Zerhusen M. A. Herpes simplex virus neurovirulence and productive infection of neural cells is associated with a function which maps between 0.82 and 0.832 map units on the HSV genome. Virology. 1989 Oct;172(2):435–450. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. L., Stevens J. G. Biological characterization of a herpes simplex virus intertypic recombinant which is completely and specifically non-neurovirulent. Virology. 1983 Nov;131(1):171–179. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Sep;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch W. J., Suhan J. P. Cellular and biochemical events in mammalian cells during and after recovery from physiological stress. J Cell Biol. 1986 Nov;103(5):2035–2052. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.5.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey D. E., Trousdale M. D., Nesburn A. B. Reactivation of murine latent HSV infection by epinephrine iontophoresis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984 Aug;25(8):945–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]