Abstract

Target-site DNA breaks increase recombination frequencies, however, the specificity of the enzymes used to create them remains poorly defined. The location and frequency of off-target cleavage events are especially important when rare-cutting endonucleases are used in clinical settings. Here, we identify noncanonical cleavage sites of I-SceI that are frequently cut in the human genome by localizing adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector-chromosome junctions, demonstrating the importance of in vivo characterization of enzyme cleavage specificity.

Introduction

Target-site DNA breaks created by rare-cutting endonucleases increase homologous recombination frequencies.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 The trend toward application of this strategy in therapeutic settings raises the concern that break-induced genomic mutations will occur at off-target locations and cause cell death or cancerous growth. Endonuclease cleavage specificity has been assayed using a variety of insensitive and nonspecific methods including toxicity as measured by the persistence of targeted cells in cultures over time,7,9,10 or a determination of the number of repair foci present in nuclease-treated cells.11,12 In some studies, a subset of specific off-target sites predicted using binding-site selection in vitro (SELEX) were also assayed for evidence of cleavage.12 The rare-cutting endonuclease I-SceI is frequently used as a control in the toxicity and repair focus assays, given its low toxicity and presumed high specificity.9,10,11,13

Each of these methods of off-target cleavage analysis falls short of identifying the sites where these enzymes cleave in vivo. The toxicity assay measures the persistence of cells co-transfected with GFP and nuclease-expressing plasmids in cultures of actively dividing cells. However, toxicity could also occur in nontargeted cell populations that express the nuclease, or manifest as unchecked growth of cells after activation of oncogenes or inactivation of tumor suppressor genes.

The repair focus assay is insensitive because fluorescent foci are relatively large and repair foci likely represent repair centers within the nucleus suggesting that the number of breaks per focus can be greater than one.14 The zinc-finger nuclease designed to cleave the CCR5 gene and currently in phase I clinical trials generated a 1.6-fold increase in the number of repair foci per nucleus.12 The significance of this finding is unclear because the number of breaks per focus is unknown, and the assay measures a particular instance in time. In comparison, the off-target activity of the I-SceI endonuclease was not significantly different from untreated cells when tested in either the toxicity9 or repair focus9,10 assays.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors integrate at pre-existing DNA breaks present in vertebrate cells.15,16,17 This aspect of AAV vector biology can be used to survey the distribution of chromosomal breaks present in the genome, allowing break-site locations to be tagged so that changes in surrounding sequence can be evaluated after repair.15,16,17 We predicted that novel cleavage sites of I-SceI and other highly specific nucleases could be identified by analyzing DNA sequences surrounding AAV-vector integration sites after treatment of cells with the nuclease and an AAV shuttle vector.

Results

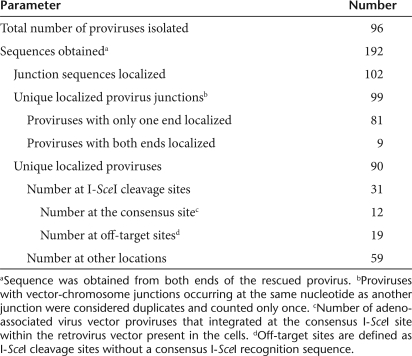

Genomic DNA was harvested from I-SceI-expressing human HT-1080 cells infected with an AAV shuttle vector, and vector-chromosome junctions were rescued by circularizing DNA fragments and transforming bacteria to antibiotic resistance encoded by vector sequences.15 The cells also contained an I-SceI site present within a retroviral vector provirus allowing integration frequencies at the consensus cleavage sequence to be compared to those at potential chromosomal sites. Ninety-six vector provirus clones were isolated and sequence was obtained from both ends of each vector (96 × 2 = 192 sequence reads, Table 1). As noted previously,17 the secondary structure of the terminal repeat at vector-chromosome junctions frequently stalled the sequencing polymerase on one of the two provirus ends resulting in the identification of chromosomal sequence from one junction of 81 clones, and both junctions of 9 clones (Table 1). Using this approach, one end of 90 vector proviruses could be localized to a unique position in the human genome.

Table 1.

Summary of sequencing and localization

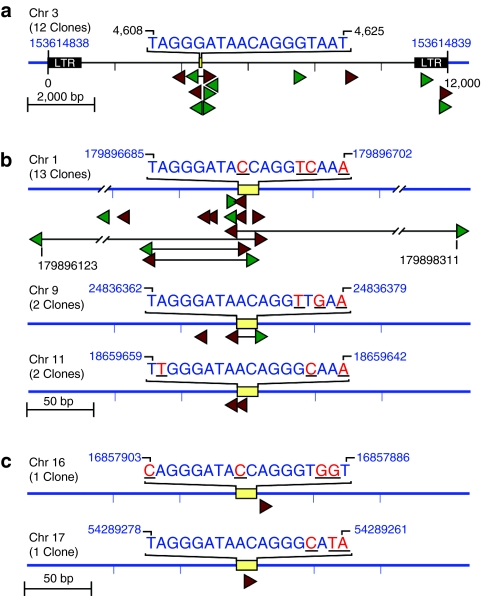

A hallmark of the nonhomologous end joining pathway of DNA repair is that nucleotides are often removed from broken chromosome ends creating deletions of varying size before ligation with the other end of the chromosome, or vector sequences. AAV vector-chromosome junctions identify the processed chromosomal end after break initiation at an adjacent location so regional DNA sequence at these 90 sites was screened to determine whether integration was initiated by I-SceI cleavage (Table 1). Twelve (13%) integrations mapped to the retrovirus target (Figure 1a). Seventeen (19%) integrations mapped to tight clusters of two or more events at three other locations where the chromosomal sequence was identical to the wild-type I-SceI cleavage sequence at 14 or 15 out of 18 base pairs (bp) (Figure 1b sites on chromosomes 1, 9, and 11). We used the sequence from these three newly discovered sites and a previously published report of I-SceI cleavage sequence variation18 to generate an 11-bp invariant sequence present at all known I-SceI sites: 5′-(GіCіA)G(GіT)ATA(AіGіCіT)C(AіC)GG-3′.

Figure 1.

Novel I-SceI cleavage sites identified by analyzing AAV-vector integration-site distributions. Vector-chromosome junction locations are shown as colored triangles below a graphic of the I-SceI site location and sequence. Junctions from the same clone are depicted as red and green triangles connected by a thin line representing deleted genomic sequence. Clones where a single junction was identified are shown as colored triangles pointing away from the integration site with green and red corresponding to different ends of the vector. The wild-type I-SceI site within the retroviral provirus, or an I-SceI-like recognition sequence present in the human genome are shown as a yellow box with flanking genomic DNA depicted as a line in black for the retrovirus, and blue for human genomic sequence. The sequence of the I-SceI site is also shown above the graphic with base pairs that differ from the wild-type sequence colored red and underlined and the genomic coordinates (NCBI Build 36.1) of the terminal base pairs labeled. The human chromosome number, and the number of unique clones represented by each graphic is also indicated. (a) AAV vector-chromosome junctions localizing to the retroviral provirus present within the cultured cells. Terminal base pair positions starting with the 5′ long-terminal repeat (LTR) of the provirus are numbered below the graphic in black. The retrovirus was localized to chromosome 3 at the genomic coordinates indicated in blue. (b) Vector-chromosome junctions where two or more sites mapped to the same genomic region are shown. (c), Single vector-chromosome junctions are shown that map to a unique chromosomal location but contain an adjacent I-SceI-like sequence identified by searching adjacent sequence with the regular expression “(GіCіA)G(GіT)ATA(AіGіCіT)C(AіC)GG”. AAV, adeno-associated virus.

The genomic DNA sequences flanking the vector-chromosome junctions of the 61 remaining clones were computationally scanned for this sequence and two additional sites were identified where junctions mapped within or near (<200 bp) of this I-SceI invariant sequence (Figure 1c, sites on chromosomes 16 and 17). No I-SceI-like sequences were found within 200 bp of 670 previously identified AAV-vector integration sites that occurred in the absence of I-SceI expression19 ruling out the possibility that these I-SceI-like recognition sequences are associated with sites of AAV vector integration by chance.

Thirty-one out of ninety AAV-vector integration events (34%) at six different locations occurred at I-SceI (12) or I-SceI-like (19) recognition sequences, revealing the presence of five novel I-SceI-cleavable sites in the human genome. Two sites on chromosomes 1 and 17 are in introns of previously described genes. All of the newly identified I-SceI-like sites could be cleaved with I-SceI by in vitro digestion of plasmids containing each sequence (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

In vitro digestion of I-SceI-like sequences. I-SceI-like sequences shown in Figure 1b,c were synthesized, cloned, and sequenced. (a) Plasmid DNA was digested for 60 minutes with 1 unit of enzyme per microgram of DNA and digested fragments separated on an agarose gel. The migration positions of linearized (I-SceI digested) and supercoiled (undigested) plasmid DNA are indicated. Cleavage of sequences from sites present on chromosomes 1 and 16 was blocked by Dcm methylation of the CCAGG (sequence). These sites were cleaved efficiently when plasmids were prepared in dcm(‐) bacteria. Lanes and sequences are labeled with wt (wild type) or the chromosome number where the sequence was found. The plasmid used to clone the sites was also digested with I-SceI as a control. (b) Box shade alignment of all I-SceI sequences described in this report, dark boxes indicate identity with the previously described wild-type (wt) I-SceI recognition sequence.

Finally, the human genome sequence was scanned computationally for sequences that meet previously published consensus criteria for I-SceI recognition, including sequence variants that showed partial cleavage activity in vitro.18 Using this strategy, we identified a single I-SceI site on chromosome 13 (21692196–21692213 human genome NCBI Build 36.1). No AAV vector integrants were found near this location despite detection of efficient cleavage of this site in vitro using Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Again, this observation highlights the discrepancy between biased searches and in vivo identification of cleavage sites.

Discussion

The I-SceI enzyme with its 18-bp recognition sequence is one of the most specific nucleases discovered to date, and is often used as a genotoxicity control in studies of engineered endonucleases.2,3,4,7,10,11,13,20 Despite this enzyme's impressive specificity, our findings show that most (19/31 = 61%) I-SceI-induced integration events occurred at novel, off-target I-SceI sites even when the wild-type cleavage site was present in the same cell, and our screen may well have failed to identify some cleavage sites. Remarkably, the site on chromosome 1 had more integrations than the wild-type I-SceI site despite four nucleotide changes from the recognition sequence, and this site lacks the previously characterized I-SceI consensus sequence (Figure 2b).18 We also demonstrated that the in silico or in vitro identification of nuclease recognition sites that meet consensus criteria does not predict cleavage locations in vivo. In addition, different cell types may have different off-target cleavage profiles based on epigenetic differences that reveal or mask potential cleavage sites. These findings highlight the need for unbiased, in vivo assessments of endonuclease cleavage sites in human cells, and they demonstrate the utility of the AAV break-capture method used here. A careful prospective analysis of this sort may prevent the genotoxicity and possible malignant transformation that could arise from unwanted double stand breaks occurring when these enzymes are used clinically.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and DNA manipulations. Plasmids pCSnZPNO,15 pDG,21 pLSceISP,15 and pA2-TOA15 have been described. Retroviral vector helper plasmid pCI-VSV-G was obtained from Garry Nolan. Plasmid sequences are available on request. Plasmids containing the consensus and variant I-SceI cleavage sites were constructed by synthesizing complementary oligonucleotides with an additional “A” added to the 3′ end and cloning of hybridized molecules into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI). Plasmids were purified using a plasmid maxi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Genomic DNAs were isolated and Southern blots were performed by standard techniques. Southern blot hybridization signals were quantified by Phosphorimager analysis (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Cell culture. Cells were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 4 g of glucose per liter (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. HT-1080 cells containing proviral target sites were generated by transduction with foamy virus vector CSnZPNO15 and selection with G418 (0.3 mg of active compound/ml). Clones of HT-1080 cells were isolated with cloning rings, and a clone containing a single-copy integrant was identified by Southern blot analysis. HT-1080 human fibrosarcoma cells have been described.22

Vector preparations. Concentrated, helper-free foamy virus vector preparations of CSnZPNO were made with plasmid pCSnZPNO as described,23 and their titers were determined by G418 selection of transduced HT-1080 cells. Murine leukemia virus (MLV) vector LSceISP was generated by transient transfection of Phoenix-GP cells with pCI-VSV-G and vector plasmids pLSceISP (1:1 ratio), replacing the culture medium 16 and 48 hours later, harvesting filtered (0.45 µm), conditioned medium after a 16 hours exposure to cells, and concentrating 50–100-fold by centrifugation.24 MLV vector titers were determined by puromycin selection. Transduction with MLV vectors was performed with polybrene (4 µg/ml concentration) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) added to the medium. Serotype 2 AAV vector AAV2-TOA was made by transfection of 293T cells with helper plasmid pDG and vector plasmids pA2-TOA respectively, benzonase-treatment of cell lysates, purification by iodixanol step gradient, heparin affinity column chromatography (HiTrap; Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden),25 and HiTrap desalting column. AAV vector titers were based on the amount of full length single-stranded vector genomes detected by alkaline Southern blot analysis.

I-SceI cleavage and AAV-vector infection. Double-strand breaks were generated at I-SceI target-site loci by seeding clonal HT-1080 cells containing the target-site provirus (CSnZPNO) at 5 × 105 cells/10-cm diameter dish on day 1, infecting with MLV vector LSceISP on day 2 (multiplicity of infection of 1 transducing unit/cell), and changing the culture medium on day 3. On day 4, cells were distributed to three 10-cm diameter dishes and selection for the MLV vector was begun with puromycin. On day 7 cells were detached with trypsin and seeded to dishes for transduction by AAV vectors. Transduction was performed by seeding 1 × 106 cells per 6-cm diameter dish on day 1, infecting with an multiplicity of infection of 3 × 104 vector containing particles per cell on day 2, transferring cells to a 15-cm diameter dish on day 4, and preparing genomic DNA from confluent dishes on day 11.

Shuttle vector rescue in bacteria. Rescue of AAV2-TOA shuttle vectors was performed as follows: 20 µg of genomic DNA containing integrated proviruses was digested with MfeI, extracted with phenol and chloroform, and precipitated with ethanol. DNA fragments were resuspended in 355 µl of H2O, brought to 400 µl with 40 µl of 10 times ligation buffer and circularized by the addition of 5 µl of T4 DNA ligase (400 u/µl; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). Ligations were incubated at 15 °C overnight, extracted with phenol and chloroform, and precipitated with ethanol. The DNA pellets were resuspended in 5 µl of H2O and Escherichia coli strain DH10B was transformed by electroporation with ~4 µg (1 µl) of DNA. Bacteria containing rescued plasmids were grown on agar containing 50 µg/ml ampicillin.

Sequence analysis. DNA sequences were processed with computer programs interpreted by the PERL programming language. Sequences were truncated at 500 bp, and expected vector-derived sequences were trimmed. The resulting junction sequences were aligned to the NCBI Build 36.1 of the human genome and a file containing the pCSnZPNO vector sequence using a stand-alone version of BLAT26 that generates a BLAST alignment score. An additional 95% homology requirement and BLAST score of >100 was used to establish genomic positions. Alignments were sorted by BLAST score and those with the five highest scores were saved for further processing. Additional PERL programs were used to remove duplicate junction sequences, and search the human genome for short sequences.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIDDK and NIH.

REFERENCES

- Jasin M, de Villiers J, Weber F., and , Schaffner W. High frequency of homologous recombination in mammalian cells between endogenous and introduced SV40 genomes. Cell. 1985;43 3 Pt 2:695–703. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo A, Genovese P, Beausejour CM, Colleoni S, Lee YL, Kim KA, et al. Gene editing in human stem cells using zinc finger nucleases and integrase-defective lentiviral vector delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1298–1306. doi: 10.1038/nbt1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteus MH., and , Baltimore D. Chimeric nucleases stimulate gene targeting in human cells. Science. 2003;300:763. doi: 10.1126/science.1078395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteus MH., and , Carroll D. Gene targeting using zinc finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:967–973. doi: 10.1038/nbt1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteus MH, Cathomen T, Weitzman MD., and , Baltimore D. Efficient gene targeting mediated by adeno-associated virus and DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3558–3565. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3558-3565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DG, Petek LM., and , Russell DW. Human gene targeting by adeno-associated virus vectors is enhanced by DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3550–3557. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3550-3557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urnov FD, Miller JC, Lee YL, Beausejour CM, Rock JM, Augustus S, et al. Highly efficient endogenous human gene correction using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nature. 2005;435:646–651. doi: 10.1038/nature03556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouet P, Smih F., and , Jasin M. Introduction of double-strand breaks into the genome of mouse cells by expression of a rare-cutting endonuclease. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8096–8106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett-Miller SM, Connelly JP, Maeder ML, Joung JK., and , Porteus MH. Comparison of zinc finger nucleases for use in gene targeting in mammalian cells. Mol Ther. 2008;16:707–717. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett-Miller SM, Reading DW, Porter SN., and , Porteus MH. Attenuation of zinc finger nuclease toxicity by small-molecule regulation of protein levels. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornu TI, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Guhl E, Alwin S, Eichtinger M, Joung JK, et al. DNA-binding specificity is a major determinant of the activity and toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Mol Ther. 2008;16:352–358. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez EE, Wang J, Miller JC, Jouvenot Y, Kim KA, Liu O, et al. Establishment of HIV-1 resistance in CD4+ T cells by genome editing using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:808–816. doi: 10.1038/nbt1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepek M, Brondani V, Büchel J, Serrano L, Segal DJ., and , Cathomen T. Structure-based redesign of the dimerization interface reduces the toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:786–793. doi: 10.1038/nbt1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby M, Mortensen UH., and , Rothstein R. Colocalization of multiple DNA double-strand breaks at a single Rad52 repair centre. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:572–577. doi: 10.1038/ncb997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DG, Petek LM., and , Russell DW. Adeno-associated virus vectors integrate at chromosome breakage sites. Nat Genet. 2004;36:767–773. doi: 10.1038/ng1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai H, Wu X, Fuess S, Storm TA, Munroe D, Montini E, et al. Large-scale molecular characterization of adeno-associated virus vector integration in mouse liver. J Virol. 2005;79:3606–3614. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3606-3614.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DG, Rutledge EA., and , Russell DW. Chromosomal effects of adeno-associated virus vector integration. Nat Genet. 2002;30:147–148. doi: 10.1038/ng824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colleaux L, D'Auriol L, Galibert F., and , Dujon B. Recognition and cleavage site of the intron-encoded omega transposase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6022–6026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DG, Trobridge GD, Petek LM, Jacobs MA, Kaul R., and , Russell DW. Large-scale analysis of adeno-associated virus vector integration sites in normal human cells. J Virol. 2005;79:11434–11442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11434-11442.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibikova M, Beumer K, Trautman JK., and , Carroll D. Enhancing gene targeting with designed zinc finger nucleases. Science. 2003;300:764. doi: 10.1126/science.1079512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D, Kern A, Rittner K., and , Kleinschmidt JA. Novel tools for production and purification of recombinant adenoassociated virus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2745–2760. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed S, Nelson-Rees WA, Toth EM, Arnstein P., and , Gardner MB. Characterization of a newly derived human sarcoma cell line (HT-1080) Cancer. 1974;33:1027–1033. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197404)33:4<1027::aid-cncr2820330419>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trobridge G, Josephson N, Vassilopoulos G, Mac J., and , Russell DW. Improved foamy virus vectors with minimal viral sequences. Mol Ther. 2002;6:321–328. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee JK, Miyanohara A, LaPorte P, Bouic K, Burns JC., and , Friedmann T. A general method for the generation of high-titer, pantropic retroviral vectors: highly efficient infection of primary hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9564–9568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S, Byrne BJ, Mason E, Zolotukhin I, Potter M, Chesnut K, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther. 1999;6:973–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent J.2001UCSC Genome Bioinformatics . < www.genome.ucsc.edu >.