Abstract

Macrophages play a critical role in the pathophysiology of liver ischemia and reperfusion (IR) injury (IRI). However, macrophages that overexpress antioxidant heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) may exert profound anti-inflammatory functions. This study explores the cytoprotective effects and mechanisms of ex vivo modified HO-1-expressing bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) in well-defined mouse model of liver warm ischemia followed by reperfusion. Adoptive transfer of Ad-HO-1-transduced macrophages prevented IR-induced hepatocellular damage, as evidenced by depressed serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (sGOT) levels and preserved liver histology (Suzuki scores), compared to Ad-β-gal controls. This beneficial effect was reversed following concomitant treatment with HO-1 siRNA. Ad-HO-1-transfected macrophages significantly decreased local neutrophil accumulation, TNF-α/IL-1β, IFN-γ/E-selectin, and IP-10/MCP-1 expression, caspase-3 activity, and the frequency of apoptotic cells, as compared with controls. Unlike in controls, Ad-HO-1-transfected macrophages markedly increased hepatic expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2/Bcl-xl and depressed caspase-3 activity. These results establish the precedent for a novel investigative tool and provide the rationale for a clinically attractive new strategy in which native macrophages can be transfected ex vivo with cytoprotective HO-1 and then infused, if needed, to prospective recipients exposed to hepatic IR–mediated local inflammation, such as during liver transplantation, resection, or trauma.

Introduction

Liver inflammation caused by ischemia and reperfusion (IR) represents an important cause of organ dysfunction, leading to the ultimate failure following liver transplantation.1 A number of putative etiological factors have been identified, including activation of Kupffer cells, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, increased expression of vascular cell adhesion molecules, and neutrophil influx.2,3 Some key mechanisms of hepatic injury include local production of reactive oxygen species, which contribute directly to initial hepatocellular damage through protein oxidation/degradation and subsequent inflammatory responses.4,5,6

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1; Hmox1), a rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of heme into biliverdin, carbon monoxide, and free iron,7 shows antioxidative cytoprotective functions.8 We have documented that HO-1 exerts potent anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic effects in models of transplant rejection and Ag-independent ischemic organ damage.9,10,11,12,13 Moreover, Ad-based HO-1 gene transfer inhibits macrophage activation in vitro and decreases macrophage infiltration in vivo,14,15 accompanied by enhanced expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2/Bcl-xl/Bag-1 (refs. 9,10). Although macrophages are the key mediators of pro-inflammatory immune responses in hepatic IRI,16,17 they are also principal HO-1 producers.13,18 Indeed, Kupffer cell depletion not only leads to diminished local HO-1 levels, but also results in an increased susceptibility to hepatic IRI.19 Alternatively, HO-1 directly exerts cytoprotection through anti-inflammatory effect on macrophage phenotype.20

In the present study, we used ex vivo modified primary bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) that overexpress HO-1 in a well-defined in vivo mouse model of liver damage due to warm IR. The results show this refined approach exerts potent cytoprotection, as evidenced by decreased serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (sGOT) levels, preservation of liver architecture, inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine programs, depression of caspase-3 activity, and apoptosis. Therefore, infusion of Ad-HO-1-transduced macrophages may provide new therapeutic means to ameliorate IR-mediated local organ damage during liver transplantation, resection, or trauma.

Results

Ad-HO-1 gene transfer induces HO-1 overexpression in BMDMs

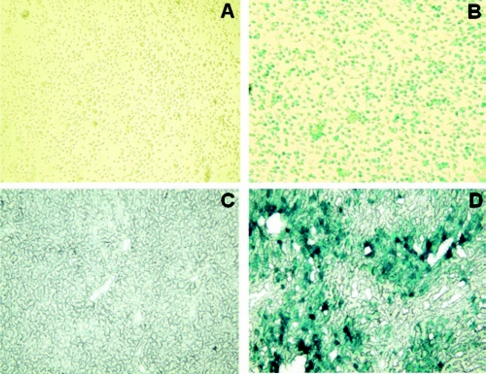

To test the efficacy of Ad-HO-1 gene transfer on primary BMDMs, we analyzed β-gal expression after cell transfection with Ad-β-gal. The X-Gal staining (blue cells) by 48 hours of transfection was >90% in BMDMs (Figure 1b), as compared with control BMDMs (Figure 1a). After in vivo adoptive transfer of Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs, the X-Gal staining in the ischemic liver lobes at 6 hours of reperfusion was 40–50% (Figure 1d and Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 1.

In vitro and in vivo X-Gal staining. (a,b) The expression of β-gal gene in bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs). Cells were transfected with Ad-β-gal, incubated for 48 hours, and then stained with X-Gal. Note: The expression of β-gal (blue cells) was >90% in BMDMs (b), as compared with control BMDMs (a). (c,d) The expression of β-gal gene in mouse livers after infusion of Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs. Note: The expression of β-gal was 40–50% in ischemic livers after transfer of BMDMs transfected with Ad-β-gal (d), as compared with control livers (c). Representative of three experiments; magnification, ×200.

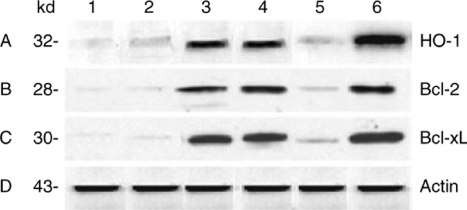

We then performed western blots to analyze HO-1 protein levels in BMDMs. As shown in Figure 2a, the expression of HO-1 was markedly increased in BMDMs transfected with Ad-HO-1 [2.0 absorbance units (AU), lane 4A], as compared with Ad-β-gal (0.5 AU, lane 5A). In contrast, HO-1 remained diminished in BMDMs pretreated with HO-1 siRNA plus cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPP), an HO-1 inducer (0.3 AU, lane 2A), as compared with nonspecific siRNA plus CoPP (1.8 AU, lane 3A).

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of HO-1, Bcl-2/Bcl-xL protein expression after transfection with Ad-HO-1/Ad-β-gal or HO-1 siRNA/NS siRNA supplemented with CoPP in BMDMs. The expression was probed by using rabbit anti-mouse HO-1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL Abs. Lane 1, BMDMs alone; lane 2, BMDMs transfected with HO-1 siRNA plus CoPP (10 µg/ml); lane 3, BMDMs transfected with nonspecific siRNA plus CoPP (10 µg/ml); lane 4, BMDMs transfected with Ad-HO-1; lane 5, BMDMs transfected with Ad-β-gal; lane 6, BMDMs plus CoPP (10 µg/ml). Note: Selectively increased expression of HO-1, Bcl-2/BclxL in Ad-HO-1-treated BMDMs (lane 4), as compared with Ad-β-gal (lane 5). Diminished expression of HO-1, Bcl-2/Bcl-xL in BMDMs treated with HO-1 siRNA plus CoPP (lane 2), compared with nonspecific siRNA plus CoPP (lane 3). Anti-β-actin Ab was used to assure equal protein amounts between samples. Data shown are representative of three separate experiments.

Ad-HO-1 gene transfer upregulates the expression of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL in BMDMs

To determine whether upregulation of HO-1 affects the expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2/Bcl-xL in BMDMs, we analyzed their protein levels by western blots. As shown in Figure 2, lanes B and C, the expression of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL was increased in Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (2.1 and 2.2 AU, lanes 4B and 4C), as compared with Ad-β-gal (0.4 and 0.6 AU, lanes 5B and 5C). In contrast, even if the presence of CoPP (HO-1 inducer), siRNA-facilitated knockdown of HO-1 in BMDMs significantly decreased Bcl-2/Bcl-xL levels (0.1 and 0.2 AU, lanes 2B and 2C), compared with nonspecific siRNA plus CoPP (1.6 and 2.1 AU, lanes 3B and 3C).

Adoptive transfer of Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs increases HO-1 mRNA expression in vivo

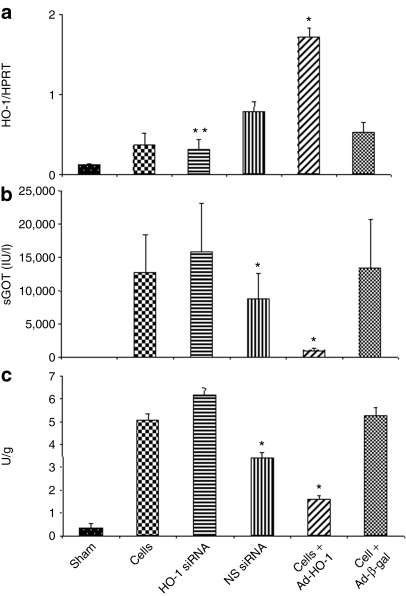

As shown in Figure 3a, liver HO-1 expression at 6 hours of reperfusion following 90 minutes of warm ischemia increased after treatment with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (P < 0.01), as compared with Ad-β-gal, HO-1 siRNA, nonspecific siRNA, or control BMDMs. In contrast, animals pretreated with HO-1 siRNA (at 4 hours prior to the ischemic insult) showed markedly diminished liver HO-1 expression, as compared with other groups (P < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Liver tissue evaluation after 90 minutes of warm ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion. (a) Quantitative RT-PCR-assisted measurement of HO-1 mRNA. Note: Increased HO-1 expression after treatment with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (*P < 0.01), as compared with Ad-β-gal. Decreased HO-1 expression in HO-1 siRNA treated group (**P < 0.005), as compared with nonspecific siRNA and Ad-HO-1 groups. Mean ± SD; n = 3–4 samples/group. (b) Hepatocellular damage, as analyzed by sGOT levels (IU/l). Note: Decreased sGOT levels in mice treated with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs, as compared to Ad-β-gal, HO-1 siRNA, or BMDMs controls (*P < 0.05). Increased sGOT levels after infusion of HO-1 siRNA, as compared with nonspecific control siRNA (*P < 0.05). Mean ± SD; n = 4–6/group. (c) Neutrophil accumulation, as analyzed by MPO enzymatic activity (U/g) in ischemic liver lobes. Note: MPO activity significantly decreased in mice treated with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs, as compared with those given Ad-β-gal or BMDMs (*P < 0.05). HO-1 siRNA increased MPO activity, as compared with nonspecific siRNA (*P < 0.05). Mean ± SD; n = 4–6/group.

Adoptive transfer of Ad-HO-1-transduced BMDMs prevents IR-induced hepatocellular damage

As shown in Figure 3b, the liver function, assessed by sGOT levels (IU/l) at 6 hours of reperfusion, was markedly improved in wild-type mice–treated Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs, as compared with those conditioned with Ad-β-gal, HO-1 siRNA, nonspecific siRNA, or control nontransfected BMDMs (1,005 ± 434 versus 13,390 ± 7,334, 15,823 ± 7,396, 8,852 ± 3,824, and 12,700 ± 5,754, respectively; P < 0.05). Knockdown of HO-1 with HO-1 siRNA but not with nonspecific siRNA prior to the ischemic insult readily increased sGOT levels (P < 0.05).

To determine whether transfer of Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs affected local neutrophil infiltration, we assessed myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (U/g) in the ischemic livers. As shown in Figure 3c, Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs livers were characterized by significantly (P < 0.05) decreased MPO activity at 6 hours (1.58 ± 0.2), compared with Ad-β-gal-BMDMs (5.24 ± 0.37), or treatment with HO-1 siRNA (6.14 ± 0.31), nonspecific siRNA (3.39 ± 0.25), or control BMDMs (5.06 ± 0.28).

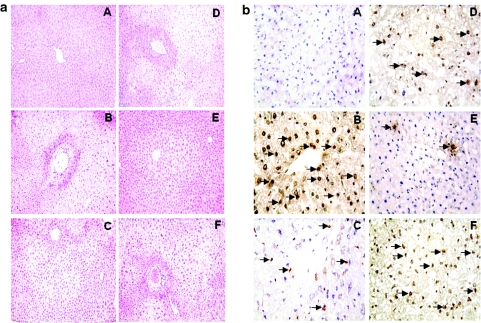

The severity of IRI was evaluated by the Suzuki classification of the hepatocellular damage (Figure 4a). The control livers in wild-type mice receiving Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs, HO-1 siRNA, or control nontransfected BMDMs revealed significant edema, severe sinusoidal congestion, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and extensive (30–50%) hepatocellular necrosis (panels F, B, and D; score, 3.3 ± 0.52, 3.5 ± 0.55, and 3.0 ± 0.63, respectively), whereas livers in wild-type recipients treated with nonspecific siRNA showed mild-to-moderate edema and sinusoidal congestion (panel C; score, 1.8 ± 0.98; P < 0.001). In marked contrast, livers in mice receiving Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs showed relatively good preservation and minimal sinusoidal congestion without edema, vacuolization, or necrosis (panel E; score, 0.8 ± 0.75; P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Histological evaluation of liver tissue after 90 minutes of warm ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion. (a) Representative histological findings. (A) Sham control; (B) treatment with HO-1 siRNA (Suzuki score = 3.5 ± 0.55); (C) treatment with nonspecific scrambled control siRNA (score = 1.8 ± 0.98); (D) treatment with BMDMs only (score = 3.0 ± 0.63); (E) treatment with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (score = 0.8 ± 0.75); (F) treatment with Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs (score = 3.3 ± 0.52); n = 4–6 mice/group; original magnification, ×200. (b) TUNEL-assisted detection of apoptosis. Note: Dense infiltration by apoptotic cells in mouse livers receiving HO-1 siRNA (B), BMDMs (D), and Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs (F), as compared with nonspecific siRNA (C; P < 0.0001). Decreased frequency of apoptotic cells in mice given Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (E; P < 0.0005), as compared with HO-1 siRNA or Ad-β-gal groups. The results were scored semiquantitatively by averaging the number of apoptotic cells (mean ± SD)/field at ×200 magnification. A minimum of six fields was evaluated/sample. Representative of 4–6 mice/group.

Adoptive transfer of Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs prevents liver cell apoptosis and caspase-3 activation

To analyze how HO-1 induction affects intrahepatic apoptotic pathway, we performed TUNEL staining on the ischemic hepatic tissue (Figure 4b). By 6 hours of reperfusion, livers treated with HO-1 siRNA, nonspecific siRNA, control BMDMs, and Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs showed increased frequency of TUNEL+ cells (34.2 ± 7.1, P < 0.0005; 16.5 ± 6.2, P < 0.0001; 23.5 ± 8.8, P < 0.0005; and 27.2 ± 7.9, P < 0.0001; panels B, C, D, and F, respectively). In contrast, the number of TUNEL+ cells remained consistently diminished after transfer of Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (4.8 ± 2.7, panel E).

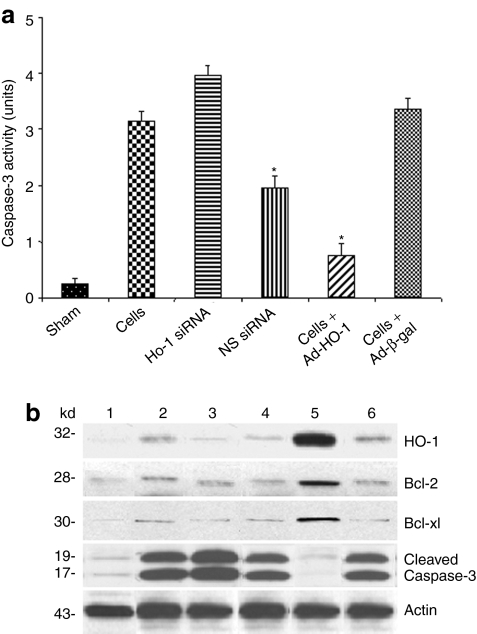

Furthermore, as shown in Figure 5a, infusion of Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs inhibited liver caspase-3 activity (0.76 ± 0.21), compared with transfer of Ad-β-gal-BMDMs (3.37 ± 0.18; P < 0.0001), HO-1 siRNA (3.96 ± 0.18; P < 0.0001), nonspecific siRNA (1.97 ± 0.21; P < 0.0005), or control BMDMs (3.15 ± 0.17; P < 0.0005).

Figure 5.

Analysis of liver tissue exposed to 90 minutes of warm ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion. (a) Caspase-3 activity. Note: Treatment with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs but not with Ad-β-gal or BMDMs alone decreased caspase-3 activity (*P < 0.001). Augmented caspase-3 levels after infusion of HO-1 siRNA, as compared with nonspecific control siRNA (*P < 0.001). Mean ± SD; n = 4–6/group. (b) Western blot analysis of HO-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, and caspase-3 gene products. Lane 1, sham; lane 2, BMDMs alone; lane 3, HO-1 siRNA; lane 4, scrambled siRNA; lane 5, Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs; lane 6, Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs. Note: Selectively increased expression of HO-1, Bcl-2/Bcl-xl, and markedly decreased cleaved caspase-3 levels in mice treated with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs, as compared with HO-1 siRNA or Ad-β-gal. Infusion of HO-1 siRNA decreased HO-1, Bcl-2/Bcl-xl, and increased cleaved caspase-3 expression. Representative of three different experiments.

Adoptive transfer of Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs facilitates induction of cytoprotective molecules

We used western blots to analyze the expression of antioxidant (HO-1), antiapoptotic (Bcl-2/Bcl-xl), and apoptotic (cleaved caspase-3) gene products in our experimental system. Their relative expression levels were determined by densitometry. As shown in Figure 5b, liver expression of HO-1 and Bcl-2/Bcl-xl was strongly upregulated after adoptive transfer of Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (2.1–2.3, 1.9–2.0, and 1.5–1.7 AU, respectively), as compared with that of Ad-β-gal (0.3–0.4 AU), HO-1 siRNA (0.2–0.3 AU), nonspecific siRNA (0.6–0.8 AU), and control BMDMs (0.2–0.4 AU) groups. In contrast, cleaved caspase-3 levels were selectively inhibited after treatment with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (0.2–0.3 AU), as compared with that of Ad-β-gal (1.8–1.9 AU), HO-1 siRNA (2.1–2.3 AU), nonspecific siRNA (0.8-1.0 AU), or control BMDMs (1.9–2.1 AU).

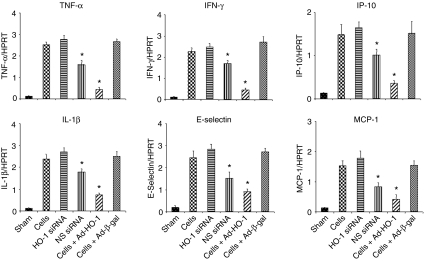

Adoptive transfer of Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs inhibits cytokine and chemokine gene expression in the liver

We used quantitative RT-PCR to analyze cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in liver ischemic lobes. As shown in Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S1, treatment with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs significantly decreased hepatic expression of mRNA coding for TNF-α (P < 0.005), IL-1β (P < 0.01), IFN-γ (P < 0.01), E-selectin (P < 0.01), IP-10 (P < 0.05), and MCP-1 (P < 0.05) as compared with transfer of Ad-β-gal-BMDMs, HO-1 siRNA, nonspecific siRNA, or control BMDMs. On the other hand, HO-1 siRNA treatment resulted in a significant increase in gene transcript levels for TNF-α (P < 0.005), IL-1β (P < 0.01), IFN-γ (P < 0.005), E-selectin (P < 0.05), IP-10 (P < 0.01), and MCP-1 (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Quantitative RT-PCR-assisted expression of mRNA coding for TNF-α/IL-1β, IFN-γ/E-selectin, and IP-10/MCP-1 in hepatic lobes at 6 hours after 90 minutes of warm ischemia. Note: The expression of TNF-α/IL-1β, IFN-γ/E-selectin, and IP-10/MCP-1 remained depressed in mice treated with Ad-HO-1-transfected BMDMs (P < 0.05), as compared with respective controls. Each column represents the mean ± SD; n = 4–6 samples/group.

Discussion

This study is the first to document the therapeutic efficacy of HO-1 expressing primary macrophages in a mouse liver warm IRI model. The systemic infusion of Ad-HO-1 BMDMs (i) prevented liver IRI, as evidenced by decreased sGOT levels, preserved hepatocyte integrity, and diminished neutrophil infiltration; (ii) suppressed hepatic apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-3 activity and upregulating antiapoptotic (Bcl-2/Bcl-xl) molecule expression; and (iii) selectively inhibited intrahepatic induction of pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules. Consistent with our findings, Froh et al. reported protection of rat livers from IRI through supplementation of Kupffer cells transduced by recombinant Ad encoding superoxide dismuthase.21 Unlike in the former study, in which <20% of injected cells localized in the rat liver, we found that 40–50% of adoptively transferred 5 × 106 BMDMs selectively sequestered in the ischemic mouse liver lobes at 6 hours of reperfusion, i.e., the peak of hepatocellular damage in our model. By 24 hours of reperfusion, we still detected 30–40% of X-Gal positive cells (data not shown), which supports the prominent role of the liver as an ultimate target organ for BMDM-based gene therapy.

Back in 1999, we reported that local induction of antioxidant HO-1 ameliorates IRI in a rat model of cold liver ischemia followed by transplantation.12 We have then documented the benefit of HO-1 overexpression to facilitate local anti-inflammatory and cytoprotection functions in mouse liver warm IRI.15 Since proposing back in 2002 that HO-1 system serves as a novel therapeutic concept in organ transplantation,22 numerous reports have confirmed the ability of local HO-1 induction, by pharmacological or genetic means, to ameliorate IRI in a plethora of transplant animal models, including heart, liver, kidney, small bowel, pancreatic islets, and muscular flap,23 data supported by findings in transplant patients.24,25 Interestingly, the human HMOX1 promoter studies based on (GT)m microsatellite polymorphism suggest that individuals with few repeats and strong HO-1 expression are less likely to develop pathologies to certain stress insults.26 This is consistent with our findings in cardiac transplant27 and liver IRI28 models where systemic induction of HO-1 was instrumental in re-establishing homeostasis in HO-1 transgenic recipients. Conversely, microsatellite polymorphism that correlates with more repeats and low HO-1 response worsens the pathology. This is consistent with HMOX1 deletion or HO-1 inhibition exacerbating the disease,26 such as enhanced local inflammation and hepatocellular damage after liver IR insult in HO-1-deficient mice.28 All these observations confirm the importance of the search for new and clinically applicable HO-1-inducing regimens. Indeed, our current x-gal assay demonstrates that BMDMs highly express HO-1 by recombinant Ad, and transfected macrophages migrate preferentially to the ischemic tissue. Moreover, systemic rather than local delivery seems more practical in the clinical setting.

Macrophages, the key mediators of immune-mediated local inflammation, are instrumental in the pathophysiology of liver IRI. Their activation triggered by ischemia promotes production of reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., as TNF-α and IL-1β) that promote initial hepatocellular damage, and further sinusoidal endothelial cell apoptosis after reperfusion.29 On the other hand, as the major source of liver HO-1, macrophages seem to be especially suitable cellular delivery system for HO-1 gene transfer. Indeed, our in vitro and in vivo data show markedly augmented HO-1 expression in BMDMs transfected with Ad-HO-1, consistent with its depression after HO-1 siRNA treatment. Similarly, in the rat model of experimental glomerulonephritis, local delivery of macrophages transfected with IL-4 and IL-10 reduced injury in the inflamed kidney and decreased macrophage infiltration in the contralateral kidney.30,31 Therefore, local macrophage delivery may exert systemic immune regulation. In our study, systemic infusion of Ad-HO-1 expressing primary macrophages produced cardinal features of successfully prevented organ IRI, i.e., decreased sGOT levels, preserved hepatocyte integrity, diminished neutrophil accumulation, and inhibited pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine programs, as well as adhesion molecules that are instrumental in local leukocyte trafficking and organ sequestration. The specificity of this therapeutic effect was confirmed when concomitant knockdown of HO-1 after HO-1 siRNA infusion readily recreated the fulminant hepatocellular damage.

Previous studies have shown that apoptosis becomes a critical mechanism in IR-triggered liver injury.16,17 The key morphological apoptotic changes are mediated by caspases, the intracellular cysteine proteases.32 In the current work, HO-1-modified macrophage delivery significantly decreased caspase-3 activity and the frequency of TUNEL+ cells in ischemic mouse livers. These are consistent with our findings on enhanced IR-induced apoptosis following HO-1 siRNA treatment, and inhibition of apoptosis via caspase 3–dependent pathway.33 Therefore, HO-1-expressing BMDMs are major antioxidant mediators with both anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic defense mechanisms in IR-induced liver inflammation.

HO-1-modified macrophage delivery selectively upregulated the expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl, consistent with their ability to inhibit IR-induced apoptosis mediated by reactive oxygen species production, cytosolic cytochrome c release, or caspase-3 activation.34,35 The induction of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL via HO-1 represents an important cytoprotective function that ameliorates IRI and prolongs orthotopic liver transplant survival.9,34 We have shown that HO-1 may exert its antiapoptotic function via carbon monoxide, an end product of HO-1 degradation.36 Thus, HO-1 action on antiapoptotic gene induction program prevents the hepatocellular and sinusoidal endothelial cell apoptosis in the ischemic liver.

In conclusion, these results establish the precedent for a novel investigative tool, and provide the rationale for a clinically attractive new strategy in which native macrophages can be transfected ex vivo with cytoprotective HO-1 ahead of time and then infused, if needed, to prospective recipients exposed to hepatic IR–mediated local inflammation, such as during liver transplantation, resection, or trauma.

Materials and Methods

Generation of recombinant Ad. The Ad-HO-1 was generated, as described.9 Briefly, the 1.0 kilobase pair rat HO-1 cDNA flanked by XhoI-Hind III sites was cloned into plasmid pAC-CMVpLpA. The resulting pAC-HO-1 plasmid was co-transfected with plasmid pJM17 into 911 cells. Recombinant Ad-HO-1 clones were screened by Southern blots. Ad containing E. coli β-galactosidase gene (Ad-β-gal) has been described.9 Isolation/propagation were carried out, and the viral titer was assessed by a plaque assay.37

Generation of L929 conditioned media and BMDMs. L929 cells (ATCC, Rockville, MD) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 2 mmol/l L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini Bio-Products, Sacramento, CA). The conditioned media was collected from cells grown for 7 days.

The BMDMs were generated according to standard procedures.38 In brief, bone marrow cells were removed from the femurs and tibias of C57BL/6 mice and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini Bio-Products), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mmol/l L-glutamine (Invitrogen), with the addition of 15% L929-conditioned medium.39 Cells were cultured at 5 × 106 cells/well for 7 days with 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C, and used for in vitro transfection.

In vitro transfection. 5 × 106 cells/well were added with Ad-HO-1 or Ad-β-gal (at multiplicity of infection 10), respectively, and incubated for 1 hour. The medium was removed and changed to Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium + 2% fetal calf serum. After 48 hours, cells were harvested for in vivo adoptive transfer. For the in vitro HO-1 expression assay, cells were transfected with siRNA using lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), and incubated for 24 hours. After washing, cells were treated with CoPP (10 µg/ml; Porphyrin Products, Logan, UT) and incubated for further 24 hours. Cells were then harvested to analyze the expression of HO-1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL.

Animals. Male C57BL/6 wild-type mice (6–8 weeks of age) were used (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) animal facility under specific pathogen-free conditions. All animals received humane care according to the criteria outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and published by National Institutes of Health (NIH publication 86-23 revised 1985).

Mouse liver IRI model. We have employed a well-defined mouse model of warm hepatic IRI followed by reperfusion.40 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg i.p.). After a midline laparotomy was performed, animals were injected with heparin (100 µg/kg), and an atraumatic clip was used to interrupt the arterial and the portal venous blood supply to the cephalad liver lobes. After 90 minutes of partial ischemia, the clip was removed, initiating hepatic reperfusion. Mice were sacrificed after 6 hours of reperfusion.

In vivo adoptive transfer of transfected BMDMs. Mice were injected with 5 × 106 of BMDMs transfected with Ad-HO-1 or Ad-β-gal (2.5 × 109 pfu; 0.1 ml over 2–3 minutes via tail vein) 24 hours prior to the onset of ischemia. HO-1 siRNA, and nonspecific or scrambled control siRNAs were given (2 mg/kg in 0.1 ml i.v.) at 4 hours prior to ischemia. Livers were harvested at 6 hours of reperfusion after 90 minutes of ischemia.

In vitro and in vivo X-Gal staining. After 5 × 106 BMDMs/well were cultured for 7 days, cells were transfected with Ad-β-gal and incubated for 48 hours. After washing, cells were fixed, and stained with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside). Cells expressing β-galactosidase (β-gal) cleave X-Gal to yield a blue chromophore in the cytoplasm. For in vivo X-Gal staining, livers were harvested and embedded with O.C.T. freezing compound, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections (6 µm thick) were fixed with 1.25% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C, and then stained with X-Gal overnight at 37 °C, as described.9 Representative areas were scored for percentage of infected (blue-stained) cells with a light microscope.

Hepatocellular damage assay. sGOT levels, an indicator of hepatocellular injury, were measured in blood samples with an autoanalyzer (ANTECH Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA).

Histology. Tissue samples were preserved in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, cut into 5-µm section, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Supplementary Figure S3). Histological severity of liver injury was graded using Suzuki's classification, in which sinusoidal congestion, hepatocyte necrosis, and ballooning degeneration are graded from 0 to 4 (ref. 41). No necrosis and congestion/centrilobular ballooning are given a score of 0, whereas severe congestion/degeneration and >60% lobular necrosis are given a value of 4.

MPO activity assay. The presence of MPO was used as an index of liver neutrophil accumulation,42 as described.9,10,11,12 One unit of MPO activity was defined as the quantity of enzyme degrading 1 µmol peroxide/minute at 25 °C per gram of tissue.

Detection of apoptosis. A commercial in situ histochemical assay (Klenow-FragEL; Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, MA) was performed to detect the DNA fragmentation characteristic of apoptosis in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded liver sections, as described.33 The results were scored semiquantitatively by averaging the number of apoptotic cells per microscopic field at ×200 magnification. Six fields were evaluated/sample.

Caspase-3 activity. Caspase-3 activity was determined by an assay kit (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), as previously described.33 For measuring the caspase-3 activity, proteins (30 µg/sample) were incubated with 200 µmol/l of enzyme-specific colorimetric caspase-3 substrate I, acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp p-nitroanilide (Ac-DEVD-pNA) at 37 °C for 2 hours. Caspase-3 activity was assessed by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 405 nm with a plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT). To determine cellular activity, the inhibitor-treated protein extracts and the purified caspase-3 (as a standard) were used.

Western blot analysis. Proteins were extracted with PBS-TDS buffer (50 mmol/l Tris, 150 mmol/l NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.2) and subjected to 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), as described.33 Polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse HO-1 (StressGen Biotech, Victoria, Canada), cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) Abs were used. The relative protein quantities, determined by densitometer, were expressed in AU.

Quantitative RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from frozen livers using RNAse Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA); RNA concentration was determined by a spectrophotometer. A total of 2.5 µg of RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA (SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System; Invitrogen). Primer sequences used for the amplification of HO-1, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IP-10, and HPRT primer sequences used for the amplification of HO-1, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IP-10, and HPRT were as follows: HO-1, 5′-TCAGTCCCAAACGTCGCGGT-3′ (forward), and 5′-GCTGTGCAGGTGTTGAGCC-3′ (reverse); TNF-α, 5′-GCCTCTTCTCATTCCTGCTTGT (forward), and 5′-GATGATCTGAGTGTGAGGGTCTG (reverse); IL-1β, 5′-TGTAATGAAAGACGGCACACC (forward), and 5′-TCTTCTTTGGGTATTGCTTGG (reverse); IFN-γ, 5′-TCTGGAGGAACTGGCAAAAG (forward), and 5′-TTCAAGACTTCAAAGAGTCTGAGG (reverse); E-selectin, 5′-TCCTCTGGAGAGTGGAGTGC (forward), and 5′-GGTGGGTCAAAGCTTCACAT (reverse); IP-10, 5′-GCTGCCGTCATTTTCTGC (forward), and 5′-TCTCACTGGCCCGTCATC (reverse); MCP-1, 5′-CATCCACGTGTTGGCTCA (forward), and 5′-GATCATCTTGCTGGTGAATGAGT (reverse); HPRT, 5′-TCAACGGGGGACATAAAAGT-3′ (forward), and 5′-TGCATTGTTTTACCAGTGTCAA-3′ (reverse).

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed, as described33 using the DNA Engine with Chromo4 Detector (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). In a final reaction volume of 25 µl, the following were added: 1× SuperMix (Platinum SYBR Green qPCR Kit; Invitrogen), cDNA and 10 µmol/l of each primer. Amplification conditions were as follows: 50 °C (2 minutes), 95 °C (5 minutes), followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C (15 seconds) and 60 °C (30 seconds).

Statistical analysis. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons between groups were analyzed by Student's t-test. All differences were considered statistically significant at the P value of <0.05.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. Quantitative RT-PCR-assisted expression of mRNA coding for CCR2 in BMDMs.Figure S2. Adoptive transfer of Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs into WT mice without hepatic ischemia and 6 h reperfusion following 90 min of ischemia.Figure S3. Adoptive transfer of BMDMs into WT mice without hepatic ischemia and 6 h reperfusion following 90 min of ischemia.

Supplementary Material

Quantitative RT-PCR-assisted expression of mRNA coding for CCR2 in BMDMs.

Adoptive transfer of Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs into WT mice without hepatic ischemia and 6 h reperfusion following 90 min of ischemia.

Adoptive transfer of BMDMs into WT mice without hepatic ischemia and 6 h reperfusion following 90 min of ischemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 DK062357, AI23847, AI42223 (J.W.K.-W.), and The Dumont Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Farmer DG, Amersi F, Kupiec-Weglinski JW., and , Busuttil RW. Current status of ischemia and reperfusion injury in the liver. Transplant Rev. 2000;14:106–126. [Google Scholar]

- Vardanian AJ, Busuttil RW., and , Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Molecular mediators of liver ischemia and reperfusion injury: a brief review. Mol Med. 2008;14:337–345. doi: 10.2119/2007-00134.Vardanian. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teoh NC., and , Farrell GC. Hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury: pathogenic mechanisms and basis for hepatoprotection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:891–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki M, Suzuki S., and , Irani K. Redox factor-1/APE suppresses oxidative stress by inhibiting the rac1 GTPase. FASEB J. 2002;16:889–890. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0664fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., and , Jackson RM. Reactive species mechanisms of cellular hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C227–C241. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00112.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarasinghe DA, Tapner M., and , Farrell GC. Role of oxidative stress in hypoxia-reoxygenation injury to cultured rat hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology. 2000;31:160–165. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines MD. The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Soares MP, Yamashita K., and , Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1: unleashing the protective properties of heme. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:449–455. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke B, Buelow R, Shen XD, Melinek J, Amersi F, Gao F, et al. Heme oxygenase 1 gene transfer prevents CD95/Fas ligand-mediated apoptosis and improves liver allograft survival via carbon monoxide signaling pathway. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1189–1199. doi: 10.1089/104303402320138970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke B, Shen XD, Lassman CR, Gao F, Busuttil RW., and , Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Cytoprotective and antiapoptotic effects of IL-13 in hepatic cold ischemia/reperfusion injury are heme oxygenase-1 dependent. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1076–1082. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen XD, Ke B, Zhai Y, Gao F, Busuttil RW, Cheng G, et al. Toll-like receptor and heme oxygenase-1 signaling in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1793–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amersi F, Buelow R, Kato H, Ke B, Coito AJ, Shen XD, et al. Upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 protects genetically fat Zucker rat livers from ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1631–1639. doi: 10.1172/JCI7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Amersi F, Buelow R, Melinek J, Coito AJ, Ke B, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 overexpression protects rat livers from ischemia/reperfusion injury with extended cold preservation. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito AJ, Buelow R, Shen XD, Amersi F, Moore C, Volk HD, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 gene transfer inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and protects genetically fat Zucker rat livers from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplantation. 2002;74:96–102. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200207150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchihashi S, Zhai Y, Bo Q, Busuttil RW., and , Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Heme oxygenase-1 mediated cytoprotection against liver ischemia and reperfusion injury: inhibition of type-1 interferon signaling. Transplantation. 2007;83:1628–1634. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000266917.39958.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Bentley RC, Madden JF., and , Clavien PA. Apoptosis of sinusoidal endothelial cells is a critical mechanism of preservation injury in rat liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1998;27:1652–1660. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli V, Selzner M, Madden JF, Bentley RC., and , Clavien PA. Endothelial cell and hepatocyte deaths occur by apoptosis after ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat liver. Transplantation. 1999;67:1099–1105. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199904270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, van de Poll MC, Greve JW, Buurman WA, Fearon KC, McNally SJ, et al. Early stress protein gene expression in a human model of ischemic preconditioning. Transplantation. 2004;78:1479–1487. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000144182.27897.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devey L, Ferenbach D, Mohr E, Sangster K, Bellamy CO, Hughes J, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages protect the liver from ischemia reperfusion injury via a heme oxygenase-1-dependent mechanism. Mol Ther. 2009;17:65–72. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco LD, Kapturczak MH, Barajas B, Wang X, Weinstein MM, Wong J, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 expression in macrophages plays a beneficial role in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2007;100:1703–1711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froh M, Wheeler MD, Smutney O, Zhong Z, Bradford BU., and , Thurman RG. New method of delivering gene-altered Kupffer cells to rat liver: studies in an ischemia-reperfusion model. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:172–183. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katori M, Busuttil RW., and , Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Heme oxygenase-1 system in organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:905–912. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200210150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares MP., and , Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1 in organ transplantation. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4932–4945. doi: 10.2741/2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner M, Böhmig GA, Schillinger M, Regele H, Watschinger B, Hörl WH, et al. Donor heme oxygenase-1 genotype is associated with renal allograft function. Transplantation. 2004;77:538–542. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000113467.36269.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baan C, Peeters A, Lemos F, Uitterlinden A, Doxiadis I, Claas F, et al. Fundamental role for HO-1 in the self-protection of renal allografts. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:811–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner M, Minar E, Wagner O., and , Schillinger M. The role of heme oxygenase-1 promoter polymorphisms in human disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1097–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo JA, Meng L, Tward AD, Hancock WW, Zhai Y, Lee A, et al. Systemic rather than local heme oxygenase-1 overexpression improves cardiac allograft outcomes in a new transgenic mouse. J Immunol. 2003;171:1572–1580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchihashi S, Livhits M, Zhai Y, Busuttil RW, Araujo JA., and , Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Basal rather than induced heme oxygenase-1 levels are crucial in the antioxidant cytoprotection. J Immunol. 2006;177:4749–4757. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindram D, Porte RJ, Hoffman MR, Bentley RC., and , Clavien PA. Platelets induce sinusoidal endothelial cell apoptosis upon reperfusion of the cold ischemic rat liver. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:183–191. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluth DC, Ainslie CV, Pearce WP, Finlay S, Clarke D, Anegon I, et al. Macrophages transfected with adenovirus to express IL-4 reduce inflammation in experimental glomerulonephritis. J Immunol. 2001;166:4728–4736. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HM, Stewart KN, Brown PA, Anegon I, Chettibi S, Rees AJ, et al. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages genetically modified to produce IL-10 reduce injury in experimental glomerulonephritis. Mol Ther. 2002;6:710–717. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. Caspase activation: revisiting the induced proximity model. Cell. 2004;117:855–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke B, Shen XD, Gao F, Qiao B, Ji H, Busuttil RW, et al. Small interfering RNA targeting heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) reinforces liver apoptosis induced by ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice: HO-1 is necessary for cytoprotection. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:1133–1142. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao G, Contreras JL, Eckhoff DE, Mikheeva G, Krasnykh V, Douglas JT, et al. Reduction of ischemia-reperfusion injury of the liver by in vivo adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 gene. Ann Surg. 1999;230:185–193. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199908000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Ito Y, Morikawa M, Uchida H, Kobune M, Sasaki K, et al. Bcl-xL gene transfer protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amersi F, Shen XD, Anselmo D, Melinek J, Iyer S, Southard DJ, et al. Ex vivo exposure to carbon monoxide prevents hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury through p38 MAP kinase pathway. Hepatology. 2002;35:815–823. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FL., and , van der Eb AJ. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley ER., and , Heard PM. Factors regulating macrophage production and growth. Purification and some properties of the colony stimulating factor from medium conditioned by mouse L cells. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:4305–4312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiser L, Gough PJ, Kodama T., and , Gordon S. Macrophage class A scavenger receptor-mediated phagocytosis of Escherichia coli: role of cell heterogeneity, microbial strain, and culture conditions in vitro. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1953–1963. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1953-1963.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen XD, Ke B, Zhai Y, Amersi F, Gao F, Anselmo DM, et al. CD154-CD40 T-cell costimulation pathway is required in the mechanism of hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury, and its blockade facilitates and depends on heme oxygenase-1 mediated cytoprotection. Transplantation. 2002;74:315–319. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200208150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Toledo-Pereyra LH, Rodriguez FJ., and , Cejalvo D. Neutrophil infiltration as an important factor in liver ischemia and reperfusion injury. Modulating effects of FK506 and cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1993;55:1265–1272. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullane KM, Kraemer R., and , Smith B. Myeloperoxidase activity as a quantitative assessment of neutrophil infiltration into ischemic myocardium. J Pharmacol Methods. 1985;14:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(85)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quantitative RT-PCR-assisted expression of mRNA coding for CCR2 in BMDMs.

Adoptive transfer of Ad-β-gal-transfected BMDMs into WT mice without hepatic ischemia and 6 h reperfusion following 90 min of ischemia.

Adoptive transfer of BMDMs into WT mice without hepatic ischemia and 6 h reperfusion following 90 min of ischemia.