Abstract

A major barrier to all oncolytic viruses (OVs) in clinical development is cellular innate immunity, which is variably active in a spectrum of human malignancies. To overcome the heterogeneity of tumor response, we combined complementary OVs that attack cancers in distinct ways to improve therapeutic outcome. Two genetically distinct viruses, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and vaccinia virus (VV), were used to eliminate the risk of recombination. The combination was tested in a variety of tumor types in vitro, in immunodeficient and immunocompetent mouse tumor models, and ex vivo, in a panel of primary human cancer samples. We found that VV synergistically enhanced VSV antitumor activity, dependent in large part on the activity of the VV B18R gene product. A recombinant version of VSV expressing the fusion-associated small-transmembrane (p14FAST) protein also further enhanced the ability of VV to spread through an infected monolayer, resulting in a “ping pong” oncolytic effect wherein each virus enhanced the ability of the other to replicate and/or spread in tumor cells. Our strategy is the first example where OVs are rationally combined to utilize attributes of different OVs to overcome the heterogeneity of malignancies and demonstrates the feasibility of combining complementary OVs to improve therapeutic outcome.

Introduction

The heterogeneity and propensity of cancers to evolve resistance mechanisms is a major impediment to the development of effective anticancer therapeutics. Oncolytic viruses (OVs) that target signaling pathways and mount a multimodality attack against tumors, have the potential to revolutionize cancer therapy.1,2,3 Indeed, recent clinical data demonstrate that OVs can be effective in controlling even highly evolved, standard therapy resistant, tumors.4,5,6,7 It is reasonable to expect that better outcomes could be achieved by combining OVs with current chemotherapeutics.8 However, the ease of manipulation of viral genomes and our more complete understanding of the biology of virus–host interactions suggests that another innovative strategy would be to create OV platforms that could complement each other in tumor destruction. We reasoned that two distinct OVs, each with their own unique arsenal of weapons and attenuating mutations, could be selected to complement the other's deficits and thus in a coinfection of tumors, provide a safe, self amplifying therapeutic. To eliminate the possibility that the complementing OVs could undergo a recombination event creating a “super virus,” we used a DNA-based poxvirus and an RNA-based rhabdovirus. Vaccinia virus (VV) is a genetically complex DNA virus encoding a large number of genes, some of which have immune evading properties allowing the virus to establish local pockets of infection within an infected host. We chose a VV [double-deleted VV (VVDD)] that is restricted to tumor cell growth as it has deletions in the virally encoded thymidine kinase and VGF genes.9 These mutations restrict the virus to productive replication in tumor cells that overexpress E2F (transcription factor that regulates cellular TK expression) and have activated epithelial growth factor receptor pathways.10,11 Particularly germane to this study, VVDD naturally expresses a viral gene product, B18R, that locally antagonizes the innate cellular, antiviral response initiated by type I interferons (IFNs).12,13,14,15 Our complementing virus of choice was an engineered version of the rhabdovirus VSV (vesicular stomatitis virus), an RNA-based virus exquisitely sensitive to the antiviral effects of type I IFNs.16,17,18 The virtues of the VSV platform are that it is genetically simple (only five gene products) allowing it to very rapidly replicate and spread within tumors, it is strongly inhibited by IFN (a clinically approved product), can be engineered to express transgenes and is immunologically distinct from VV. We present evidence here that these two virus platforms have synergistic oncolytic activity against a range of distinct tumor types both in vitro and in vivo.

Results

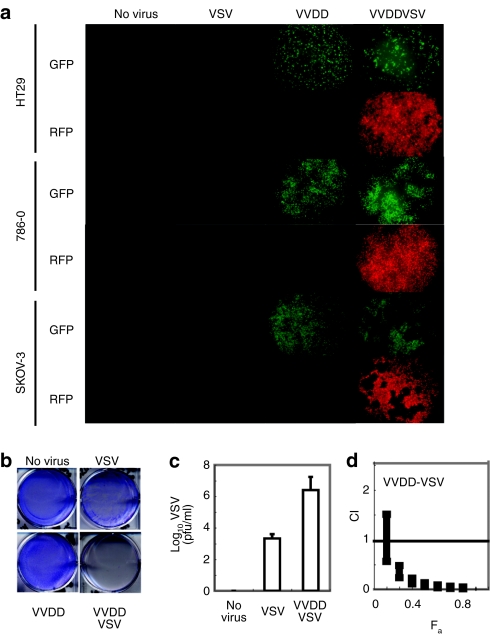

VV enhances VSV infection in vitro

The wild-type strain of VSV expresses a protein (the M or matrix protein) that upon infection acts as an intracellular antagonist of IFN production by blocking the transport of IFN mRNAs from the nucleus.17 In earlier studies, we reported that a variant of the virus (VSVΔ51) with an engineered mutation in the M protein is unable to block the expression of IFN genes following virus infection and thus has restricted growth in normal cells that have an intact antiviral response.17 VSVΔ51 grows to levels comparable to wild-type virus in a broad spectrum of cancer cells that lack either the ability to produce or respond to IFN.17 However, some human tumor cell lines HT29 (colon), SKOV-3 (ovary), and 786-O (kidney) retain at least partial responsiveness to IFN and only poorly support the spread of VSVΔ51 (Figure 1a–c). We confirmed, however, that these VSVΔ51 resistant cell lines can be productively infected by an oncolytic version of vaccinia (Figure 1a) described above and herein referred to as VVDD.9 Following infection, VVDD expresses a gene product, B18R, that binds to and locally sequesters the antiviral cytokines IFN-α/β.12,14,19 To test the idea that VVDD, through the expression of B18R, could sensitize resistant tumor cells to VSV infection, we created tagged versions of VVDD [enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)] and VSVΔ51 (red fluorescent protein) that would allow us to monitor the ability of each of the viruses to spread within a coinfected culture. For instance, the HT29 cells supported VVDD infection although at low multiplicities of infection, (MOI 0.1 pfu/cell) 48 hours was insufficient time for VVDD to spread throughout the monolayer (as measured by GFP expression) or complete killing of the culture (Figure 1a,b). If VVDD infection was followed by a 1,000 times lower dose of VSVΔ51, we observed both a rapid spread of VSV and complete killing of the HT29 cell culture (Figure 1a,b). This was true of the SKOV-3 and 786-O tumor cell lines as well (Figure 1a). These experiments demonstrate the ability of VVDD to initiate infection of a cancer cell line and create a local environment that sensitizes a previously resistant culture to the rapid oncolytic effects of VSV. As expected, the accelerated spread of VSVΔ51 correlated with a 1,000-fold increase in virus production compared to singly infected cultures (Figure 1c). Isobologram analysis revealed that coinfection with the two viruses resulted in synergistic killing of the cancer cell lines (Figure 1d). Examination under fluorescence microscope revealed that, in general, the red fluorescent protein and GFP images did not overlap, suggesting that increased oncolysis was not due to enhanced uptake of VSV in VV-infected cells but rather due to sensitization of neighboring cells to VSVΔ51 infection (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Synergistic cytotoxic effects of vaccinia (VVDD) and VSVΔ51 combination treatment on various cancer cell lines. (a) HT29, 786-O or SKOV-3 were left untreated or treated with VVDD-eGFP [0.1 multiplicity of infection (MOI)] for 2 hours, or with VSVΔ51DsRed (0.0001 MOI HT29, SKOV-3; 0.1 for 786-O) for 45 minutes, or in combination, VVDD for 2 hours and 4 hours later with VSVΔ51 during 45 minutes. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (VV) and DsRed (VSV) fluorescence were detected 48 hours after VSVΔ51 infection. One of three independent experiments. (b) 72 hours after VSVΔ51 infection, viral oncolytic effect was assessed by a crystal violet assay. One of three independent experiments. (c) VSV titers were determined 48 hours after infection. Mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. (d) Isobologram analysis: 786-O cells were treated with serial dilutions of VVDD followed by VSV. Cytotoxicity was assessed using alamar blue reagent after 72 hours. Combination indexes (CIs) were calculated using Calcusyn software according to the method of Chou and Talalay. Plots represent the algebraic estimate of the CI in function of the fraction of cells affected (Fa). Error bars: mean ± SEM. One of two independent experiments in quadruplicate.

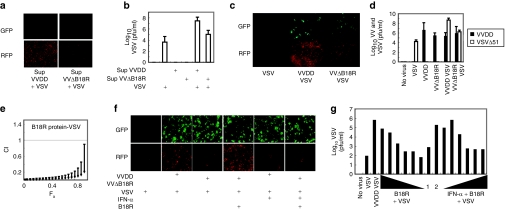

The VV B18R gene product enhances VSV replication in HT29 cancer cell lines in vitro

Our hypothesis was that local production of B18R (or other factors) following infection of tumor cells with VVDD creates a microenvironment depleted of bioactive antiviral cytokines thus permitting robust replication and spread of VSVΔ51. To test this idea, we first determined the IFN responsiveness of HT29 colon cancer cells by pretreating cultures with IFN-α for 17 hours followed by VSVΔ51. HT29 cells were protected from infection by VSVΔ51 but retained some susceptibility to vaccinia infection at the concentration of IFN used (Supplementary Figure S1). Next, we tested whether a factor secreted by VVDD infected cells was responsible for the sensitization of HT29 cells to VSVΔ51 infection. Supernatants from VVDD infected cultures were collected 24 hours after infection, filtered (to remove VVDD) and applied to naive cultures of HT29 cells. These cultures were subsequently infected with VSVΔ51 and as shown in Figure 2a, a factor(s) present in the supernatants of VVDD infected cultures was sufficient to sensitize HT29 cells to infection by VSV. To determine whether the B18R protein was at least partially responsible for the enhancement of VSVΔ51, we developed a recombinant VV strain lacking the B18R gene (VVΔB18R-eGFP). HT29 cells were infected with either VVDD or VVΔB18R alone or in combination with VSVΔ51. Infection of HT29 cells by VSVΔ51 was greatly enhanced by VVDD but much less by the VVΔB18R virus (Figure 2c). This enhancement was reflected in the amounts of VSVΔ51 produced from coinfected cultures (Figure 2d) with 100 times more VSVΔ51 produced in VVDD coinfected cultures than in VVΔB18R coinfections. As expected, filtered supernatants from VVΔB18R infected cultures were much less potent than supernatants from VVDD infected cultures at promoting VSVΔ51 spread and virus production in HT29 cells (Figure 2a,b). Finally, purified recombinant B18R protein when added to HT29 cultures directly was able to support, in a dose dependent fashion, robust growth and spread of VSVΔ51 (Figure 2e,g) as well as complement the VVΔB18R virus in enhancing VSVΔ51 infection of HT29 cells (Figure 2f). The activity of B18R protein (Supplementary Figure S1) could be overcome by supplementing cultures with exogenous IFN-α. This is an important observation as it demonstrates that the spread of VSVΔ51 is restricted by the relative ratios of B18R and IFN-α arguing that in vivo, the growth of VSVΔ51 will be limited by the relative concentration of B18R in the tumor microenvironment.

Figure 2.

Vaccinia virus B18R gene product enhances vesicular stomatitis virus expression in HT29 cancer cell lines. (a) HT29 were treated or not with VVDD-eGFP or VVΔB18R-eGFP [0.1 multiplicity of infection (MOI)] for 2 hours. Supernatant of each condition was filtered at 0.22 µm. Filtrated media was added to naive HT29. A VSVΔ51-DsRed (0.0001 MOI) infection was performed or not for 45 minutes. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and DsRed were detected 48 hours after infection. One of three independent experiments. (b) VSV titers were determined. Mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. (c) HT29 were treated or not with VVDD-eGFP or VVΔB18R-eGFP (0.1 MOI) for 2 hours alone, or in combination with VSVΔ51-DsRed (0.0001 MOI) for 45 minutes. eGFP and DsRed were detected 48 hours after. One of three independent experiments. (d) Viral titers were determined after infection as in c. Black and white bars: VV and VSV. Mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. (e) Isobologram: 786-O cells were treated with serial dilutions of B18R gene product followed by VSV and processed as Figure 1d. CI: Combination index. Fa: fraction of cells affected. Error bars: mean ± SEM. One of two independent experiments in quadruplicate. (f) HT29 were pretreated or not with IFN-α (30 IU) and treated or not with VVDD or VVΔB18R-eGFP (0.1 MOI) for 2 hours. In the last 45 minutes, VSVΔ51-DsRed (0.0001 MOI) was added in combination or not with recombinant B18R (0.01 µg). eGFP and red fluorescent protein (RFP) were detected 48 hours after. One of two independent experiments. (g) HT29 were pretreated or not with various concentration of recombinant B18R (0.1–10−6 µg) protein during 2 hours and treated with VVDD-eGFP or VVΔB18R-eGFP (0.1 MOI) for 2 hours. VSVΔ51-DsRed (0.0001 MOI) was added with or not various concentration of IFN-α (5–30 IU). Supernatants were collected for VSVΔ51 titration 48 hours later. 1: VVDB18R + VSV, 2: VVDB18r + B18R + VSV. One experiment is presented.

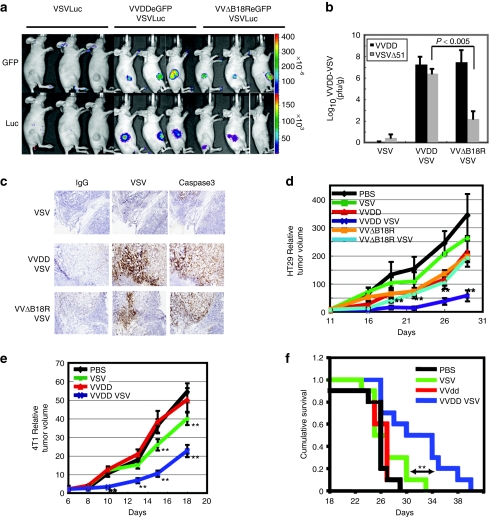

VV enhances VSVΔ51 replication specifically in tumor beds

Nude mice bearing human HT29 subcutaneous tumors were injected intravenously with VVDD-eGFP, and the duration and biodistribution of viral infection was monitored by noninvasive optical imaging (in vivo imaging system) (Supplementary Figure S2). As expected, 3 days after infusion, VVDD gene expression was restricted to sites of human tumor growth.9,20,21 At this time, VSVΔ51-luciferase was administered intravenously and the expression of the virally encoded reporter monitored over time (Supplementary Figure S2). We observed VSVΔ51-associated luciferase expression in tumors only in doubly infected animals. The VSVΔ51-luciferase signal peaked at ~7 days after infection but remained detectable by in vivo imaging system in the tumor for up to 11 days after infection. Importantly, during our daily monitoring of infected animals, we never observed “off-target” infections of normal tissues. We compared and contrasted VVDD and VVΔB18R viruses for their ability to promote VSV replication in tumor bearing mice (Figure 3a,b). Although both viruses could enhance VSVΔ51 replication specifically in tumors, their relative potency in this respect mirrored our in vitro studies described above. Indeed when VVΔB18R/VSVΔ51 coinfected tumors were harvested, homogenized and analyzed for virus titers by plaque assay, we found 1,000 times more VSVΔ51 in VVDD infected tumors than in VVΔB18R infected tumors (Figure 3b). The presence and disposition of VSV in human tumors were determined by immunohistochemical staining with anti-VSV antibodies. Although tumors infected only with VSV had little or no detectable viral proteins, as expected, there was evidence of widespread VSV infection in coinfected tumors (Figure 3c). As we have demonstrated previously,22 infection of tumors with VSV leads to widespread induction of apoptosis as revealed by immunohistochemical detection of active caspase 3 (Figure 3c). We expected that with the enhanced replication of VSV in dually infected tumors, we should observe improved therapeutic outcomes. Indeed, this was the case in both human xenograft and immune competent mouse breast tumor models (Figure 3d–f). At the treatment doses used in these experiments, we found that therapy with either virus on its own had little impact on these rapidly growing tumors and did not significantly impact cumulative survival. However when VVDD and VSV were sequentially administered, we were able to significantly slow tumor growth. In addition, the combination treatment could significantly extend survival as compared to all other treatment arms, a considerable improvement given the aggressiveness of the 4T1 breast tumor model. Most importantly in these mouse experiments, we found that virus replication even in coinfected animals was restricted to tumor beds with no evidence of infection of normal tissues detected by imaging (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S2), immunohistochemical staining (Figure 3c), and in a safety study (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 3.

Vaccinia virus enhances vesicular stomatitis virus expression into human in vivo tumor. (a) HT29 subcutaneous xenograft tumor models were established in nude mice. Group received VVDD or VVΔB18R-eGFP (1 × 106 pfu) and 2 days after, VSVΔ51-luciferease (1 × 107 pfu) was also injected intravenously. Viral replication at tumor site was imaged using in vivo imaging system 6 days after VSVΔ51 injection for GFP and luciferase. Three representative mice per group are presented. (b) In vivo tumors were homogenized and titrations were performed for each mouse of the groups (VSVΔ51 and VVΔB18R/VSVΔ51 N = 5, VVDD/VSVΔ51 N = 9). Bars correspond to SEM. t-Test between VVDD/VSVΔ51 and VVΔB18R/VSVΔ51 groups. (c) Tumor frozen sections were used for IgG, anti-VSV and caspase 3 immunohistochemistry analysis. (d) HT29 model was established in nude mice. 10 days later, viruses were injected as previously described. Size of tumor was monitored for each groups (N = 4) and average tumor volumes relative to D14 are shown. Bars correspond to the SEM. **P < 0.05 [analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing VVDD/VSV to VVDB18r/VSV]. (e) 4T1 (1 × 105 cells) subcutaneous graft tumor models were established in immunocompetent mice. Six days later (palpable tumors) animals were treated by intravenous injection with VVDD (1 × 107 pfu/dose) and/or VSV (1 × 108 pfu/dose). Size of tumor was monitored for each groups (N = 10) and average tumor volumes relative to D6 are shown. Bars correspond to the SEM. **P < 0.05 (ANOVA comparing VVDD/VSV to VSV; VSV to PBS or VVDD). Similar results were obtained in two other independent experiments (N = 7) with 4T1 (3 ×105 cells). (f) Cumulative survival rate of 4T1 experimentation described in e was evaluated according to treatment groups. **Kaplan–Meier statistic comparing VSV group to the combination viruses group, LogRank = 6.3, P value = 0.0121. Similar results were obtained in two other independent experiments (Ntotal = 17).

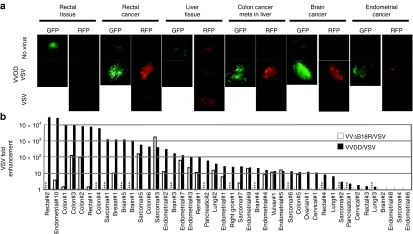

VV enhances VSV expression in human tumor tissues ex vivo

The experiments described above demonstrate synergistic interactions between vaccinia and VSV oncolytics in established tumor cell lines and animal models; however, we sought to test how frequently this would be observed in intact primary human biopsy samples. Human tissue explants with specific pathologies (Supplementary Table S1), including both tumor and normal tissue (when available), were obtained from patients undergoing surgical resection. Tissue slices were prepared from each sample and then infected singly or in combination with OVs as described in Figure 4. Viral infection was visualized by fluorescence microscopy after 48 hours. In all experiments, uninfected slices were visualized by epifluorescence microscopy to determine the level of background fluorescence emanating from the tissue. Figure 4a shows representative images of enhanced VSV infection in primary tumor samples in the presence of VVDD. For example, in one patient we were able to obtain both rectal tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue and consistent with our mouse models, we observed OV growth only in tumor slices and not in adjacent normal tissue. Similar results were seen in a paired normal and tumor sample from a patient with metastatic colon cancer in the liver (Figure 4a). The fluorescent images provide a qualitative readout; but to confirm that we were seeing productive infections in these samples, we quantified the amount of virus produced from the infected cultures. For these studies, immediately following the adsorption of virus, separate samples were taken to provide a baseline for the remaining input virus. At 48 hours after infection, slices were homogenized and virus titers determined. The results presented in Figure 4b are the fold enhancement of VSVΔ51 in doubly versus singly infected cultures in a wide range of malignancies. In 33 of 44 tumor samples, we observed a 10–10,000-fold increase in VSV titers following coinfection of tumor samples with VV (Figure 4b). In available adjacent normal samples we observed no significant infection with VSVΔ51 in the absence or presence of VVDD.

Figure 4.

Vaccinia virus enhances vesicular stomatitis virus expression into human ex vivo tumor. (a) Human ex vivo rectal cancer and normal tissue, colon cancer metastases in liver and normal liver, brain and endometrial cancer tissues were inoculated with 1 × 108 pfu of VVDD-eGFP with or not VSVΔ51-DsRed. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and DsRed expression was monitored by fluorescence microscopy 48 hours after inoculation. (b) Summary of ex vivo tumor tissue sample. VSVΔ51 virus titers were determined to quantify viral replication. Each line corresponds to one patient [type of tumor and number of patient (#)]. Black and white bars: VSVΔ51-fold enhancement in doubly with VVDD (44 patients) and VVΔB18R (30 patients) compared to singly infected cultures. Combination VV/VSVΔ51 samples were infected by VVDD (1 × 107 pfu) and/or VSVΔ51 (1 × 108 pfu). Samples were processed for titration 48 hours after inoculation. Data were classified from the highest increase to the lowest one for VVDD/VSV combination. *** Not available data. A paired t-test stastistic comparing VVDD/VSV to VVDB18R/VSV. Samples tested for both VVDD/VSV and VVΔB18R/VSV were included for the statistic test. P < 0.05.

VSVΔ51 can be engineered to enhance VVDD growth

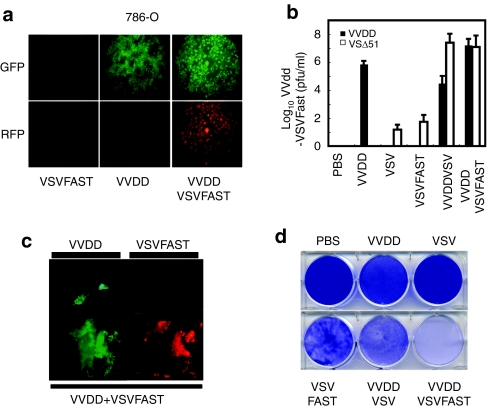

Clearly, VVDD can enhance VSVΔ51 growth by conditioning the tumor microenvironment to be nonresponsive to antiviral cytokines like IFN. We sought to create a VSVΔ51 strain that could reciprocate and produce a virally encoded gene product that would enhance VVDD growth and/or spread. Approximately 90% of VVDD produced during an infection remains inside the infected cell throughout the virus growth cycle,23,24 and we reasoned that if we could enhance the dissemination of VVDD from the initial infected cell, the overall virus production would be increased. To this end, we created a VSVΔ51 recombinant that expresses a fusion-associated small-transmembrane (p14 FAST) protein that locally induces cell fusion.25,26 The p14 FAST protein is a small integral membrane protein originally isolated from a reptilian reovirus that spontaneously initiates cell membrane fusion. We challenged the 786-O kidney cancer cell line using concentrations of viruses insufficient to elicit complete killing by either VSV or VVDD (Figure 5a,d). In in vitro and ex vivo coinfection experiments, we found that VVDD and VSVFAST interacted in a synergistic fashion with increased cell killing (Figure 5c and Supplementary Figure S4), virus spread of both viruses translating in over 100-fold increase in VV production (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

VSVΔ51FAST enhances VVDD growth. (a) 786-O were left untreated or treated with VVDD-eGFP (0.1 MOI) for 2 hours and VSVFAST-DsRed (0.1 MOI) infection was then performed or not for 45 minutes. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (VV) and DsRed (VSVFAST) fluorescence were detected 48 hours by microscopy after VSVFAST infection. One of three independent experiment. (b) VVDD and VSVFAST titers 48 hours after infection. Mean ± SEM from three independent experiment. (c) Patient colon tumor specimen was infected by VVDD (eGFP) (1 × 107 pfu) and/or VSVFAST (DsRed) (1 × 108 pfu). eGFP and DsRed expression was monitored 48 hours after viral inoculation. (d) 72 hours after VSVFAST infection, viral oncolytic effect was assessed by a crystal violet assay. One of two independent experiments.

Discussion

Replicating OVs have been designed or selected to specifically infect cancers and unlike tailored small molecule inhibitors, OVs attack tumors in multiple ways including direct tumor lysis, modulating tumor perfusion, and stimulation of tumor-directed innate and adaptive immune responses.2,3,22,27 We hypothesized that it should be possible to combine two distinct but complementary OV platforms to achieve better anticancer activity particularly in poorly permissive cancer types. We chose oncolytic candidates from the orthopox and rhabdovirus families for several reasons. VVDD used here grows preferentially in cancer cells that have activated epithelial growth factor receptor/ras pathways and overexpress the transcription factor E2F. The virtues of the VV platform include its highly selective growth in malignancies, its ability to be delivered intravenously, extensive safety profile in humans, large capacity to encode transgenes, and its unique complement of viral genes that modulate the environment around the primary site of infection facilitating local virus spread. VSV, on the other hand, is an RNA-based virus that has a very simple genome and has evolved a strategy of extremely rapid replication and spread to avoid innate antiviral immune responses. Indeed, one striking observation in these studies was the ability of VSV to “catch up” and surpass vaccinia spread in tumor cultures even when added at a 1,000 times lower initial inoculum.

Safety concerns have been paramount in the development of OV therapeutics and a great deal of effort has been put into the selection of viruses that have low toxicity. Unfortunately many of these attenuated platforms, while safe, have shown only limited efficacy in early human trials.28,29 Indeed, there have been several recent studies to engineer or select more potent viruses by including virulence genes into attenuated strains with the hope of making more clinically efficacious strains.6,30 A concern with this approach is the perceived, if not real, possibility of creating an “andromeda strain” virus that on its own can overcome the antiviral programs normal cells have in place to control virus spread. As an alternative to the creation of a single more virulent virus and the associated safety concerns that would go with it, we have used a genetic complementation strategy. We propose using two distinct and safe attenuated viruses that would complement each other's tumor killing abilities but were unable to grow on their own or in combination in normal cells. An important observation from this study is that, at least in the animal models tested here, the enhancement of virus growth was restricted to the tumor bed (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S2a). We believe the reason for this is twofold. First, both strains are highly restricted for growth only in tumor cells. Second, the effects of the B18R protein are concentration dependent and thus only impact the immediate environment around the infected cell. Our studies with IFN demonstrate the concentration dependence of B18R for antagonizing this cytokine (Supplementary Figure S1b). Another critical feature of the approach described here is that opportunities for our two viruses to undergo direct recombination are eliminated as they use distinct genetic backbones (RNA versus DNA).

One of the virtues of the OV platform is the ease with which viruses can be engineered and it seems likely that additional therapeutic value can be created by engineering complementing viruses that express gene products capable of further enhancing virus spread and/or efficacy. As, but one example, we engineered a fusion protein into VSV that we reasoned could enhance VV spread. We showed that indeed a “ping pong” effect was created wherein vaccinia augmented VSV growth by expression of B18R and in return VSV expression of the fusion protein enhanced vaccinia growth (Supplementary Figure S4). Given OV therapy is known to be associated with initiation of an adaptive immune response, one can imagine creating viruses expressing immune stimulating cytokines that may be most active when expressed sequentially. In this vein, another virtue of complementing virus platforms that we have yet to explore would be ability to effect a “prime boost” phenomena wherein the patient's immune response becomes focused on tumor antigens as two immunologically distinct virus platforms are used to effect tumor lysis. As it seems important to give multiple virus doses to achieve maximal therapeutic benefit, treatment with complementing immunologically distinct viruses may circumvent or mitigate antiviral immune responses and allow prolonged therapeutic delivery of OVs.

Materials and Methods

Compounds. Intron A (Shering, Kenilworth, NJ) at 10 × 106 IU/ml. Recombinant B18R protein was from eBioscience (0.1 mg/ml; (San Diego, CA)).

Cell lines. HT29, SKOV-3, 786-O, U2OS, 4T1, Vero cells were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and propagated in HyQ Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (High glucose) (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (CanSera, Etobicoke, Canada).

Viruses. VVs: The B18R deleted strain of Western Reserve was provided by Thorne (Pittsburgh, PA). VVDD-eGFP and the pSEL-eGFP plasmid were provided by McCart (Toronto, ON).9 Vaccinia ΔB18R-eGFP (VVΔB18R-eGFP) was made by insertion of eGFP-DNA into vaccinia thymidine kinase (TK) gene by homologous recombination. Successful recombinants were selected by eGFP expression and plaque-purified. All VV were propagated in U2OS. VSVs: Recombinant AV3 strain of VSV with red fluorescent protein (VSVΔ51-DsRed), or luciferase (VSVΔ51-Luc) were propagated in Vero cells.31 Virions were purified as previously described.26

Isobologram analysis. 786-O cells were plated at 50,000 cells per well in 96-wells plate. Next day serial dilutions of VVDD and VSVΔ51 were added keeping a constant ratio of 100:1. Alamar blue reagent was used to assess cellular metabolic activity after 72-hour incubation. Calcusyn was used to compute the combination index, where combination index < 0.7 is considered synergistic.32 Combination index error bars represent the standard deviation estimate.

Mice and tumor models. Mice were from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA).

Imaging studies: HT29 (3 × 106) tumors were established subcutaneously in 6-week-old CD1 female nude mice (N = 4). Palpable tumors formed within ~10 days after seeding. VVDD-eGFP was administered intravenously (1 × 106 pfu/mouse). VSV-Luc (1 × 107 pfu) was administered intravenously 2–3 days after VV treatment.

Efficacy studies: HT29 xenograft model mice were treated and tumors measured every 3–4 days using an electronic caliper. Tumor volume was calculated as (L1)2 × L2/2. 4T1 (1 × 105 cells) model (N = 10) and repeated in two other independent experiments (3 × 105 cells, N = 7), balb-c mice were treated with VVdd (1 × 107 pfu) and 2 days later with VSV (1 × 108 pfu). Tumors were measured as previously described. All experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines review board for animal care (University of Ottawa).

In vivo imaging. Mice were injected with D-luciferin (Molecular Imaging Products, Ann Arbor, MI) for firefly luciferase imaging. Mice were anesthetized under 3% isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) and imaged with IVIS200 Series Imaging System (Xenogen, Hopkinton, MA). Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Living Image v2.5 software. For each experiment, images were captured under identical exposure, aperture and pixel binning settings, and bioluminescence is plotted on identical color scales.

Immunohistochemistry. Tissues were harvested, placed in OCT mounting media (Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Sectioned tissues were processed as previously described with anti-VSV (1:5,000; 30 minutes) or Anti-Active Caspase 3 (1:200, 60 minutes) (25). Tumor images were obtained with an Epson Perfection 2450 Photo Scanner (Epson, Toronto, Canada) whereas magnifications were captured using a Zeiss Axiocam HRM Inverted fluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Toronto, Canada) and analyzed using Axiovision 4.0 software.

Explant tissues. Primary cancer and normal tissues specimens were obtained from consenting patients who underwent tumor resection. Samples were manually divided using a 15 mm scalpel blade into ~10-mm3 pieces and placed on 12 wells plate with alpha medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum under sterile techniques. VVΔB18R or VVDD were added at 107 pfu and allowed to infect for 2 hours at 37 °C. In the last 45 minutes, VSVΔ51DsRed (108 pfu) was added before covering specimens with medium. At 48 hours, specimens were visualized using fluorescence microscopy. Samples were then weighted, homogenized using a homogenizer (Kinematica AG-PCU-11). Viral titers were quantified by standard plaque assay. Institutional review board of Ottawa Hospital Research Institute has approved all human studies. Declaration of Helsinki protocols were followed and patients gave their written, informed consent.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. IFN-α experimentation. A) 75% confluent HT29 colon cancer cells were pretreated or not with IFN α (IntronA at 30IU) for 17 hours. Then, cells were left untreated or treated with VVDD-eGFP (0.1 MOI) for 2 hours, or with VSVΔ51-DsRed (0.0001 MOI) for 45 minutes alone or in the combination, VVDD for 2 hours and VSVΔ51 for the last 45 minutes. eGFP (VV) and DsRed (VSV) fluorescence were detected 48 hours after VSVΔ51 infection. As expected, pictures show that VSVΔ51 alone poorly replicate in these cells. At the contrary, in combination with VVDD, VSVΔ51 replicate in HT29. In comparison, with IFN α pre-treatment?, even if VVDD can infect and spread, VSVΔ51 was not enhanced. One of two independent experimentations is presented. B) 75% confluent HT29 colon cancer cells were pre-treated or not with various concentration of recombinant B18R protein (10e-1 to 10e-6μg). DsRed (VSV) fluorescence was detected 48 hours after VSVΔ51 infection. One of two independent experimentations is presented.Figure S2. Vaccinia virus enhances vesicular stomatitis virus expression into human in vivo tumor. A) HT29 subcutaneous xenograft tumour models were established in nude mice. After tumour growth, group received VVDD-eGFP (1.10e6pfu) and 2 days after, VSVΔ51-Luciferease (1.10e7pfu) was also injected intravenously. Viral replication at tumour site was imaged using IVIS imaging system at day 3, 7 and 9 after VSVΔ51 injection for GFP and Luciferase. Tumour mice corresponding to combination treatments, shown a strong signal of VSVΔ51 after 5 days until day 9. (B) Nude mice were injected by intravenous with VVDD-eGFP (1.10e6pfu/mice). GFP associated expression in tumour tissue was controlled by microscope 2 days after intravenous injection in live mice. (C) At days 11 after VSVΔ51 injection, mice were sacrificed. Tumours were removed by surgery and placed on a plate to verify the specific expression of VSVΔ51 into the tumour. Combination treatment tumour mice shown more abundant presence of VSVΔ51.Figure S3. Combination vaccinia virus/rhabdovirus is safe in immunocompetent mice. A) VSV (green curve) and VV (red curve) alone or combination VV-VSV (blue curve) were injected at therapeutic doses and time as previously described in naïve immunocompetent mice. Global balb-c mice health was followed monitoring their weight during 3 weeks after injections. B) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV at therapeutic doses as previously described. Five days after VSV injection, three mice were sacrificed and following organs were collected for VSV titration (grey bars): brain, heart, kidney, liver, lungs, ovaries. Bars correspond to the SEM. C) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV in combination with VVDD at therapeutic doses and time as previously described. Five days after VSV injection, three mice were sacrificed and following organs were collected for VSV (grey bars) and VV (black bars) titration: brain, heart, kidney, liver, lungs, ovaries. Bars correspond to the SEM. D) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV-DsRed alone (up panels) or with a combination VVDD-eGFP + VSV-DsRed (low panels) at therapeutic doses and time as previously described. One week after VSV injection, three mice of each groups were sacrificed and following organs were collected for pictures. BF: Brightfiel illumination; RFP: Red fluorescence for VSV; GFP: Green fluorescence for VV.Figure S4. VVDD-VSVΔ51FAST combination enhances dramatic cancer cell issue. (A) Isobologram analysis: 786-0 were processed like in Figure 1D. CI: Combination indices. Fa: fraction of cells affected. Error bars: +/-SEM. One of two independent experiments in quadruplicate. (B) Percentage of cell death was assessed. 786-O were treated with VVDD and VSV or VSVFAST. Cytotoxicity was assessed by MTS reagent after 72h. One of two independent experiments in duplicate. C) 786-O were treated or not with VVDD (0.1 MOI) for 2h and/or VSVFAST (0.1 MOI) for 45 min. eGFP (VV) fluorescence was detected 48h after infection. One of two independent experiment.Table S1. Ex vivo table with patient information. Tumors were grouped by type of cancer. Each line corresponds to one patient. Date of birth (D.O.B.), Gender and pathology finding were indicated. n/a: Not available.

Supplementary Material

IFN-α experimentation. A) 75% confluent HT29 colon cancer cells were pretreated or not with IFN α (IntronA at 30IU) for 17 hours. Then, cells were left untreated or treated with VVDD-eGFP (0.1 MOI) for 2 hours, or with VSVΔ51-DsRed (0.0001 MOI) for 45 minutes alone or in the combination, VVDD for 2 hours and VSVΔ51 for the last 45 minutes. eGFP (VV) and DsRed (VSV) fluorescence were detected 48 hours after VSVΔ51 infection. As expected, pictures show that VSVΔ51 alone poorly replicate in these cells. At the contrary, in combination with VVDD, VSVΔ51 replicate in HT29. In comparison, with IFN α pre-treatment?, even if VVDD can infect and spread, VSVΔ51 was not enhanced. One of two independent experimentations is presented. B) 75% confluent HT29 colon cancer cells were pre-treated or not with various concentration of recombinant B18R protein (10e-1 to 10e-6μg). DsRed (VSV) fluorescence was detected 48 hours after VSVΔ51 infection. One of two independent experimentations is presented.

Vaccinia virus enhances vesicular stomatitis virus expression into human in vivo tumor. A) HT29 subcutaneous xenograft tumour models were established in nude mice. After tumour growth, group received VVDD-eGFP (1.10e6pfu) and 2 days after, VSVΔ51-Luciferease (1.10e7pfu) was also injected intravenously. Viral replication at tumour site was imaged using IVIS imaging system at day 3, 7 and 9 after VSVΔ51 injection for GFP and Luciferase. Tumour mice corresponding to combination treatments, shown a strong signal of VSVΔ51 after 5 days until day 9. (B) Nude mice were injected by intravenous with VVDD-eGFP (1.10e6pfu/mice). GFP associated expression in tumour tissue was controlled by microscope 2 days after intravenous injection in live mice. (C) At days 11 after VSVΔ51 injection, mice were sacrificed. Tumours were removed by surgery and placed on a plate to verify the specific expression of VSVΔ51 into the tumour. Combination treatment tumour mice shown more abundant presence of VSVΔ51.

Combination vaccinia virus/rhabdovirus is safe in immunocompetent mice. A) VSV (green curve) and VV (red curve) alone or combination VV-VSV (blue curve) were injected at therapeutic doses and time as previously described in naïve immunocompetent mice. Global balb-c mice health was followed monitoring their weight during 3 weeks after injections. B) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV at therapeutic doses as previously described. Five days after VSV injection, three mice were sacrificed and following organs were collected for VSV titration (grey bars): brain, heart, kidney, liver, lungs, ovaries. Bars correspond to the SEM. C) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV in combination with VVDD at therapeutic doses and time as previously described. Five days after VSV injection, three mice were sacrificed and following organs were collected for VSV (grey bars) and VV (black bars) titration: brain, heart, kidney, liver, lungs, ovaries. Bars correspond to the SEM. D) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV-DsRed alone (up panels) or with a combination VVDD-eGFP + VSV-DsRed (low panels) at therapeutic doses and time as previously described. One week after VSV injection, three mice of each groups were sacrificed and following organs were collected for pictures. BF: Brightfiel illumination; RFP: Red fluorescence for VSV; GFP: Green fluorescence for VV.

VVDD-VSVΔ51FAST combination enhances dramatic cancer cell issue. (A) Isobologram analysis: 786-0 were processed like in Figure 1D. CI: Combination indices. Fa: fraction of cells affected. Error bars: +/-SEM. One of two independent experiments in quadruplicate. (B) Percentage of cell death was assessed. 786-O were treated with VVDD and VSV or VSVFAST. Cytotoxicity was assessed by MTS reagent after 72h. One of two independent experiments in duplicate. C) 786-O were treated or not with VVDD (0.1 MOI) for 2h and/or VSVFAST (0.1 MOI) for 45 min. eGFP (VV) fluorescence was detected 48h after infection. One of two independent experiment.

Ex vivo table with patient information. Tumors were grouped by type of cancer. Each line corresponds to one patient. Date of birth (D.O.B.), Gender and pathology finding were indicated. n/a: Not available.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research awarded to B.D.L., H.A., and J.C.B.; the Terry Fox Foundation awarded to J.C.B. and H.A., an Industrial Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research-Jennerex partnership (F.L.B.), a Fellowship from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (J.-S.D.). J.C.B. was supported by the Joe and Amy Ip Fund.

REFERENCES

- Bell JC. Oncolytic viruses: what's next. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:127–131. doi: 10.2174/156800907780058844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parato KA, Senger D, Forsyth PA., and , Bell JC. Recent progress in the battle between oncolytic viruses and tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:965–976. doi: 10.1038/nrc1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton AM., and , Kirn DH. From ONYX-015 to armed vaccinia viruses: the education and evolution of oncolytic virus development. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:133–139. doi: 10.2174/156800907780058862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SJ., and , Peng KW. Viruses as anticancer drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BH, Hwang T, Liu TC, Sze DY, Kim JS, Kwon HC, et al. Use of a targeted oncolytic poxvirus, JX-594, in patients with refractory primary or metastatic liver cancer: a phase I trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:533–542. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TC, Hwang T, Park BH, Bell J., and , Kirn DH. The targeted oncolytic poxvirus JX-594 demonstrates antitumoral, antivascular, and anti-HBV activities in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1637–1642. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirn D. Clinical research results with dl1520 (Onyx-015), a replication-selective adenovirus for the treatment of cancer: what have we learned. Gene Ther. 2001;8:89–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Gao L, Yeagy B., and , Reid T. Virus combinations and chemotherapy for the treatment of human cancers. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2008;10:371–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCart JA, Ward JM, Lee J, Hu Y, Alexander HR, Libutti SK, et al. Systemic cancer therapy with a tumor-selective vaccinia virus mutant lacking thymidine kinase and vaccinia growth factor genes. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8751–8757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr MJ, Manome Y, Tanaka T, Wen P, Kufe DW, Kaelin WG, Jr, et al. Tumor-selective transgene expression in vivo mediated by an E2F-responsive adenoviral vector. Nat Med. 1997;3:1145–1149. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne SH, Hwang TH, O'Gorman WE, Bartlett DL, Sei S, Kanji F, et al. Rational strain selection and engineering creates a broad-spectrum, systemically effective oncolytic poxvirus, JX-963. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3350–3358. doi: 10.1172/JCI32727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons JA, Alcamí A., and , Smith GL. Vaccinia virus encodes a soluble type I interferon receptor of novel structure and broad species specificity. Cell. 1995;81:551–560. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcamí A., and , Smith GL. Vaccinia, cowpox, and camelpox viruses encode soluble gamma interferon receptors with novel broad species specificity. J Virol. 1995;69:4633–4639. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4633-4639.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colamonici OR, Domanski P, Sweitzer SM, Larner A., and , Buller RM. Vaccinia virus B18R gene encodes a type I interferon-binding protein that blocks interferon alpha transmembrane signaling. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15974–15978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.15974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcamí A, Symons JA., and , Smith GL. The vaccinia virus soluble alpha/beta interferon (IFN) receptor binds to the cell surface and protects cells from the antiviral effects of IFN. J Virol. 2000;74:11230–11239. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11230-11239.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojdl DF, Lichty B, Knowles S, Marius R, Atkins H, Sonenberg N, et al. Exploiting tumor-specific defects in the interferon pathway with a previously unknown oncolytic virus. Nat Med. 2000;6:821–825. doi: 10.1038/77558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojdl DF, Lichty BD, tenOever BR, Paterson JM, Power AT, Knowles S, et al. VSV strains with defects in their ability to shutdown innate immunity are potent systemic anti-cancer agents. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichty BD, Stojdl DF, Taylor RA, Miller L, Frenkel I, Atkins H, et al. Vesicular stomatitis virus: a potential therapeutic virus for the treatment of hematologic malignancy. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:821–831. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancová I, La Bonnardiere C., and , Kontsek P. Vaccinia virus protein B18R inhibits the activity and cellular binding of the novel type interferon-delta. J Gen Virol. 1998;79 (Pt 7):1647–1649. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-7-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCart JA, Mehta N, Scollard D, Reilly RM, Carrasquillo JA, Tang N, et al. Oncolytic vaccinia virus expressing the human somatostatin receptor SSTR2: molecular imaging after systemic delivery using 111In-pentetreotide. Mol Ther. 2004;10:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.06.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik AM, Chalikonda S, McCart JA, Xu H, Guo ZS, Langham G, et al. Intravenous and isolated limb perfusion delivery of wild type and a tumor-selective replicating mutant vaccinia virus in nonhuman primates. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:31–45. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbach CJ, Paterson JM, Lemay CG, Falls TJ, McGuire A, Parato KA, et al. Targeted inflammation during oncolytic virus therapy severely compromises tumor blood flow. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1686–1693. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss B., and , Earl PL. Overview of the vaccinia virus expression system. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2001;Chapter 5:Unit5.11. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0511s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss B. Poxvirus entry and membrane fusion. Virology. 2006;344:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy EK., and , Duncan R. Reovirus FAST protein transmembrane domains function in a modular, primary sequence-independent manner to mediate cell-cell membrane fusion. J Virol. 2009;83:2941–2950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01869-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CW, Stephenson KB, Hanson S, Kucharczyk M, Duncan R, Bell JC, et al. The p14 FAST protein of reptilian reovirus increases vesicular stomatitis virus neuropathogenesis. J Virol. 2009;83:552–561. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01921-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne SH., and , Contag CH. Combining immune cell and viral therapy for the treatment of cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1449–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6550-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghi M., and , Martuza RL. Oncolytic viral therapies – the clinical experience. Oncogene. 2005;24:7802–7816. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TC, Galanis E., and , Kirn D. Clinical trial results with oncolytic virotherapy: a century of promise, a decade of progress. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:101–117. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TC., and , Kirn D. Systemic efficacy with oncolytic virus therapeutics: clinical proof-of-concept and future directions. Cancer Res. 2007;67:429–432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power AT, Wang J, Falls TJ, Paterson JM, Parato KA, Lichty BD, et al. Carrier cell-based delivery of an oncolytic virus circumvents antiviral immunity. Mol Ther. 2007;15:123–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

IFN-α experimentation. A) 75% confluent HT29 colon cancer cells were pretreated or not with IFN α (IntronA at 30IU) for 17 hours. Then, cells were left untreated or treated with VVDD-eGFP (0.1 MOI) for 2 hours, or with VSVΔ51-DsRed (0.0001 MOI) for 45 minutes alone or in the combination, VVDD for 2 hours and VSVΔ51 for the last 45 minutes. eGFP (VV) and DsRed (VSV) fluorescence were detected 48 hours after VSVΔ51 infection. As expected, pictures show that VSVΔ51 alone poorly replicate in these cells. At the contrary, in combination with VVDD, VSVΔ51 replicate in HT29. In comparison, with IFN α pre-treatment?, even if VVDD can infect and spread, VSVΔ51 was not enhanced. One of two independent experimentations is presented. B) 75% confluent HT29 colon cancer cells were pre-treated or not with various concentration of recombinant B18R protein (10e-1 to 10e-6μg). DsRed (VSV) fluorescence was detected 48 hours after VSVΔ51 infection. One of two independent experimentations is presented.

Vaccinia virus enhances vesicular stomatitis virus expression into human in vivo tumor. A) HT29 subcutaneous xenograft tumour models were established in nude mice. After tumour growth, group received VVDD-eGFP (1.10e6pfu) and 2 days after, VSVΔ51-Luciferease (1.10e7pfu) was also injected intravenously. Viral replication at tumour site was imaged using IVIS imaging system at day 3, 7 and 9 after VSVΔ51 injection for GFP and Luciferase. Tumour mice corresponding to combination treatments, shown a strong signal of VSVΔ51 after 5 days until day 9. (B) Nude mice were injected by intravenous with VVDD-eGFP (1.10e6pfu/mice). GFP associated expression in tumour tissue was controlled by microscope 2 days after intravenous injection in live mice. (C) At days 11 after VSVΔ51 injection, mice were sacrificed. Tumours were removed by surgery and placed on a plate to verify the specific expression of VSVΔ51 into the tumour. Combination treatment tumour mice shown more abundant presence of VSVΔ51.

Combination vaccinia virus/rhabdovirus is safe in immunocompetent mice. A) VSV (green curve) and VV (red curve) alone or combination VV-VSV (blue curve) were injected at therapeutic doses and time as previously described in naïve immunocompetent mice. Global balb-c mice health was followed monitoring their weight during 3 weeks after injections. B) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV at therapeutic doses as previously described. Five days after VSV injection, three mice were sacrificed and following organs were collected for VSV titration (grey bars): brain, heart, kidney, liver, lungs, ovaries. Bars correspond to the SEM. C) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV in combination with VVDD at therapeutic doses and time as previously described. Five days after VSV injection, three mice were sacrificed and following organs were collected for VSV (grey bars) and VV (black bars) titration: brain, heart, kidney, liver, lungs, ovaries. Bars correspond to the SEM. D) Immunocompetent mice were injected with VSV-DsRed alone (up panels) or with a combination VVDD-eGFP + VSV-DsRed (low panels) at therapeutic doses and time as previously described. One week after VSV injection, three mice of each groups were sacrificed and following organs were collected for pictures. BF: Brightfiel illumination; RFP: Red fluorescence for VSV; GFP: Green fluorescence for VV.

VVDD-VSVΔ51FAST combination enhances dramatic cancer cell issue. (A) Isobologram analysis: 786-0 were processed like in Figure 1D. CI: Combination indices. Fa: fraction of cells affected. Error bars: +/-SEM. One of two independent experiments in quadruplicate. (B) Percentage of cell death was assessed. 786-O were treated with VVDD and VSV or VSVFAST. Cytotoxicity was assessed by MTS reagent after 72h. One of two independent experiments in duplicate. C) 786-O were treated or not with VVDD (0.1 MOI) for 2h and/or VSVFAST (0.1 MOI) for 45 min. eGFP (VV) fluorescence was detected 48h after infection. One of two independent experiment.

Ex vivo table with patient information. Tumors were grouped by type of cancer. Each line corresponds to one patient. Date of birth (D.O.B.), Gender and pathology finding were indicated. n/a: Not available.