Abstract

Follicular lymphoma has considerable clinical heterogeneity, and there is a need for easily quantifiable prognostic biomarkers. Microvessel density has been shown to be a useful prognostic factor based on numerical assessment of vessel numbers within histologic sections in some studies, but assessment of tumor neovascularization through angiogenic sprouting may be more relevant. We therefore examined the smallest vessels, single-staining structures measuring less than 30 μm2 in area, seen within histologic sections, and confirmed that they were neovascular angiogenic sprouts using extended focal imaging. Tissue microarrays composing diagnostic biopsies from patients at the extremes of survival of follicular lymphoma were analyzed with respect to numbers of these sprouts. This analysis revealed higher angiogenic activity in the poor prognostic group and demonstrated an association between increased sprouting and elevated numbers of infiltrating CD163+ macrophages within the immediate microenvironment surrounding the neovascular sprout.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) patients have an indolent clinical course with a median survival of 10 years, but the clinical course is very heterogeneous; some patients have rapid disease progression and short survival,1 with worse prognosis in those patients who transform to a more aggressive histology.2,3 The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index4,5 helps to risk-stratify patients but has limited discriminative power, and additional prognostic biomarkers providing insight into underlying disease biology are urgently required.

The use of simple, numerical quantification of blood vessels in histologic sections as a prognostic marker in FL has provided conflicting results.6,7 An inherent limitation of conventional microvessel density analyses on histologic sections is that it provides only a relatively thin, 2-dimensional representation of the 3-dimensional, branching network of tumor vasculature and a static snapshot of the dynamic process of tumor neovascularization. We sought to establish whether the smallest-sized vascular structures, lacking a lumen, which are seen in routine sections, correspond to angiogenic sprouts; and whether quantifying these vascular sprouts could provide an improved surrogate measure of angiogenic activity and its effect on subsequent clinical outcome.

The immune microenvironment in FL is intimately linked to clinical behavior and response to treatment,8–10 and increased numbers of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in FL diagnostic biopsies indicate adverse prognosis,11 although this appears to be dependent on treatment used.12,13 Macrophages adapt to activation signals in their environment and display plasticity of phenotype when activated. TAMs exhibit an alternatively activated (M2) phenotype, which is proangiogenic,14 tumor-promoting, and a potential target for anticancer therapy.15 We used a panel of macrophage markers to quantify macrophage numbers within the immediate microenvironment of neovascular sprouts and identify any association between the extent of angiogenic sprouting and number of TAMs as well as their impact on clinical outcome, based on predefined analysis areas assigned on linked serial sections using image analysis software.

Methods

Patient samples, controls, and TMA

An extreme of survival tissue microarray (TMA)16 was prepared from 1-mm-diameter cores from patients whose survival from diagnosis was less than 5 years (n = 34) and greater than 15 years (n = 25) selected from patients diagnosed with FL at St Bartholomew's Hospital between 1974 and 1999. Treatment was variable during the 35-year period under review, and patients were treated according to the current protocol during this period. Of note, only 2 patients received rituximab-containing regimens, in both cases after the 15 year cut-off point, therefore not affecting the assignment to the prognostic groups. Reactive follicular hyperplasia lymph node samples (n = 12) were arrayed as controls. All patients provided informed consent for excess biopsy tissue to be used for research purposes in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from the North East London Research Board (05/Q0605/140).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry staining was performed16 for CD31, CD34, CD68 (KP1), CD68 (PG-M1), and VWF (Dako Denmark), LYVE-1, Prox-1, Podoplanin, and CD11c (Abcam), and CD163 (Novocastra). Double immunofluorescence labeling of CD31 in combination with CD68 (KP1), CD68 (PG-M1), CD11c, and CD163 was also performed.17

Vessel quantification, image analysis, and scoring

Vessels were quantified using a computerized image analysis system (Ariol, Applied Imaging, Genetix) using pathologist-trained visual parameters. Distinction was made between interfollicular vessels and those within neoplastic follicles based on the characteristic vascular distribution in FL.18 The software generated vessel numbers and vessel size and allowed further analysis restricted to a defined vessel area. Macrophage density was assessed by absolute macrophage number using image analysis and scored semiquantitatively based on cells/high power field by 2 pathologists (M.C., A.M.L.). Location to the neoplastic follicle was recorded.

Analysis areas restricted to the 200-μm diameter were applied to CD163-stained TMA sections. These areas were identified using a subsequent section stained with CD31. The 2 sections were linked by identifying several landmarks used as anchor points. The software offset rotational and expansion differences between the 2 sections. Interfollicular sprouting structures, measuring less than 30 μm2, were identified using the software, and a corresponding analysis area surrounding the sprout was applied to the CD163-stained section A maximum of 15 analysis areas, spread over 3 triplicate cores, were taken per patient biopsy. Any overlap between analysis areas was avoided where possible.

Extended focal imaging of tumor vasculature

Immunofluorescence labeling of CD31 was performed on 50-μm-thick whole sections in both prognostic subgroups. After selection of a capillary or postcapillary venule, focal series were acquired through the depth of the section. Extended focal imaging on the focal series was then performed using the image analysis software CellF Version 24 (Olympus), generating a composite image from differently focused single frames. Digital image processing allowed reconstruction of a 3-dimensional topographic height map of the sample. Vascular processes were classified as sprouts if they were blind-ended and clearly originating from the main vessel body.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using a generalized mixed-effects model with a patient being a random effect and survival status being a fixed effect. The null model was that the counts were Poisson distributed with the patient being the sole effect, and the alternative model included the survival status as an additional effect. P values were calculated using χ2 analysis of variance between the 2 models, and the R function “lmer” from the lme4 package was used. Correlation was performed using Spearman rank coefficient.

Results and discussion

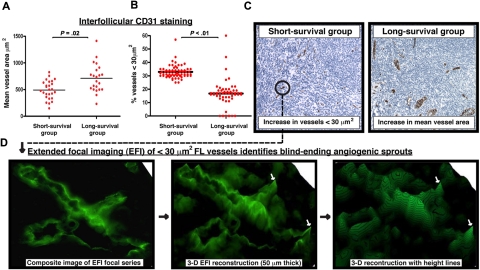

Diagnostic FL biopsies were chosen for study from patients at the extremes for overall survival.16 Initial analysis of vessel numbers, regardless of size, revealed no significant difference between prognostic groups with any of the endothelial cell markers used (data not shown). Analysis restricted to the interfollicular area demonstrated significantly reduced mean vessel area assessed by CD31 staining in the short-survivor group (P = .02; Figure 1A,C). This difference was driven by increased numbers of small, vascular structures measuring less than 30 μm2 (P < .01; Figure 1B-C). To determine whether these structures represented blind-ending sprouting processes, we performed extended focal imaging on 50-μm-thick whole sections. We found numerous examples of vascular sprouting in all samples analyzed and used software to reconstruct their 3-dimensional structure (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Increase in the presence of small vessels in poor prognosis FL identified as angiogenic sprouts using extended focal imaging. (A) CD31 was examined using TMA cores from extremes of survival diagnostic FL biopsies (< 5-year short-survival group and > 15-year long-survival group). Dot-plot chart shows significantly decreased interfollicular CD31+ mean vessel area (μm2) in the short-survival group. Each dot represents an FL patient (mean of triplicate cores) using the TMA. (B) Dot-plot chart shows significantly increased interfollicular CD31+ vascular structures measuring less than 30 μm2 in the short-survival group. Each dot represents a single core (triplicate cores per patient) using the FL extremes of survival TMA. Statistical analysis was performed using a mixed-effects linear model (P values). The black bar represents the mean value for each experimental group. (C) Representative low power (original magnification ×20) images of CD31 interfollicular staining on TMA cores from the short-survival group (left-hand image) and the long-survival group (right-hand image). Note the increase in small, vascular structures measuring less than 30 μm2 in the poor prognosis FL biopsy. The long-survival group exhibited larger mean vessel areas. Image acquisition: Olympus BX61 camera (Applied Imaging), 20×/0.5 numeric aperature (NA); images imported to Ariol Genetix Version 3.2.125 (Applied Imaging). (D) CD31 vascular structures present in the extremes of survival FL TMAs were examined using extended focal imaging (EFI). This technique builds a composite image of a focal series from 50-μm-thick whole sections that can be reconstructed with height lines in 3 dimensions (3-D) using image analysis software (process denoted by black arrows). This EFI analysis identified that the CD31+ vessels measuring less than 30 μm2 in the short-survival FL group (C ●) were blind-ending sprouting processes. The white arrows indicate blind-ending vessels in the poor prognosis FL biopsies identified using EFI. Image acquisition: Olympus BX61 camera (Applied Imaging), 40×/0.75 NA; images constructed by CellF Version 24 (Olympus).

Surprisingly, the increased number of angiogenic sprouts in the poor prognosis group was only highlighted with CD31, an antigen expressed on both blood and lymphatic endothelial cells, but not with other endothelial markers analyzed that are specific to vascular endothelial cells only.19 The difference appears the result of CD31-expressing vascular channels because analysis with lymphatic specific markers (Podoplanin, LYVE-1, and prox-1) showed no difference between the 2 prognostic groups.

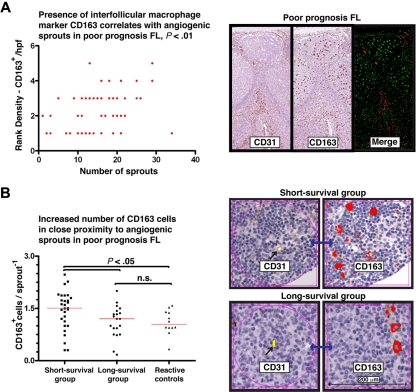

The increased angiogenic activity in the poor prognostic group was observed only in the interfollicular region, making it less probable that this results from tumor-cell driven angiogenesis. We therefore examined the immune infiltrate in the interfollicular area, with particular attention paid to areas with angiogenic sprouts. CD163, a member of the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich superfamily restricted to monocyte/macrophage lineage, is a useful marker for anti-inflammatory or alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages).20 We found a correlation between numbers of CD163+ TAM and angiogenic sprouts in the poor prognostic group as assessed both by the histopathologists (Spearman r = 0.4263, P < .01, 95% confidence interval = 0.1880-0.6171; Figure 2A) and the automated system (Spearman r = 0.3145, P < .01, 95% confidence interval = 0.1349-0.4742). Analysis restricted to 200-μm areas immediately surrounding these vascular sprouts revealed increased numbers of CD163+ cells compared with reactive controls and those in the good prognostic group (P = .05) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Elevated CD163+ macrophages correlate and are in close proximity with angiogenic sprouts in poor prognosis FL. (A) Dot-plot chart shows a positive correlation (Spearman rank coefficient, r = .43) of interfollicular CD163+ cells (rank density) with the numbers of CD31+ sprouting vessels (< 30 μm2). Representative images are shown on the right-hand side of CD31 and CD163 staining in the short-survival FL group using serial TMA sections. The merge image shows immunofluorescent analysis of these markers using a single section. Image acquisition: Olympus BX61 camera (Applied Imaging), 20×/0.5 NA; images imported to Ariol Genetix Version 3.2.125 (Applied Imaging). (B) Dot-plot chart shows significantly increased CD163+ macrophages in close proximity (within 200 μm) to a CD31+ sprouting vessel in the short-survival FL group compared with the long-survival group and reactive follicular hyperplasia controls. Each dot represents an average number of CD163+ macrophages from 15 analysis areas (200-μm area immediately surrounding a CD31+ sprouting vessel) for each patient sample. The red bar represents the mean value for each experimental group. Statistical analysis was performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test (GraphPad Prism Version 5.03 software; P values). Representative images are shown on the right-hand side of CD31 (labeled yellow using Ariol Genetix Version 3.2.125 analysis software [Applied Imaging]) and CD163 (labeled red) staining in the short- and long-survival FL TMA groups using linked serial TMA sections with Ariol image analysis software. Note the increase numbers of CD163+ macrophages within close proximity (200 μm, black arrow) to a CD31+ sprouting vessel (linked section, blue arrow) in the short-survival group (top images) compared with the long-survival group (bottom images).

Our results demonstrate an association between TAMs and angiogenic sprouting in the interfollicular area in FL. A relationship has been seen between macrophage infiltration and vascular density in human breast cancer,21 renal cell carcinoma,22 salivary gland carcinoma,23 and basal cell carcinoma.24 We are currently investigating mechanisms whereby TAMs drive this process and how to block this process as a potential therapeutic strategy. Of note, in the developing mouse eye, Wnt7b production by macrophages directs vascular remodeling of hyaloid vessels,25,26 and this mechanism may contribute to tumor progression in primary mammary tumors,27 where Wnt7b expression was enriched in a subpopulation of “invasive” TAMs. In keeping with our previous study16 and those of others,9,28 we noted no association between number of CD68-expressing cells and outcome either overall or in interfollicular areas. The reason why CD163-expressing, but not CD68-expressing, macrophages are associated with vascular sprouts is currently under investigation, but CD163 may represent a better marker of M2 macrophages and have higher Wnt7b expression. Further work is required to establish the importance of this proposed mechanism and its relevance to lymphoid malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cancer Research United Kingdom and by the National Cancer Institute (P01 CA95426; J.G.G.).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.J.C. designed and performed experiments and wrote the paper; J.G.G. and T.A.L. designed the research, supervised the study, and wrote the paper; K.J.M. performed experiments; A.G.R. and S.H. contributed to the research and wrote the paper; A.M.L. and M.C. provided expert histopathologic scoring; G.K. provided expert statistical analysis; and F.M. provided analysis of outcome.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: John G. Gribben, Institute of Cancer, Barts and the London School of Medicine, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, United Kingdom; e-mail: j.gribben@qmul.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Johnson PW, Rohatiner AZ, Whelan JS, et al. Patterns of survival in patients with recurrent follicular lymphoma: a 20-year study from a single center. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):140–147. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen MH, Lister TA, Brearley RI, Shand WS, Stansfeld AG. Histological transformation of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a prospective study. Cancer. 1979;44(2):645–651. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197908)44:2<645::aid-cncr2820440234>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montoto S, Davies AJ, Matthews J, et al. Risk and clinical implications of transformation of follicular lymphoma to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2426–2433. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solal-Celigny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood. 2004;104(5):1258–1265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Federico M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2: a new prognostic index for follicular lymphoma developed by the international follicular lymphoma prognostic factor project. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4555–4562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vacca A, Ribatti D, Ruco L, et al. Angiogenesis extent and macrophage density increase simultaneously with pathological progression in B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(5):965–970. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koster A, van Krieken JH, Mackenzie MA, et al. Increased vascularization predicts favorable outcome in follicular lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(1):154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dave SS, Wright G, Tan B, et al. Prediction of survival in follicular lymphoma based on molecular features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(21):2159–2169. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glas AM, Knoops L, Delahaye L, et al. Gene-expression and immunohistochemical study of specific T-cell subsets and accessory cell types in the transformation and prognosis of follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(4):390–398. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong D. Molecular pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma: a cross talk of genetic and immunologic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(26):6358–6363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.26.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farinha P, Masoudi H, Skinnider BF, et al. Analysis of multiple biomarkers shows that lymphoma-associated macrophage (LAM) content is an independent predictor of survival in follicular lymphoma (FL). Blood. 2005;106(6):2169–2174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Jong D, Koster A, Hagenbeek A, et al. Impact of the tumor microenvironment on prognosis in follicular lymphoma is dependent on specific treatment protocols. Haematologica. 2009;94(1):70–77. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canioni D, Salles G, Mounier N, et al. High numbers of tumor-associated macrophages have an adverse prognostic value that can be circumvented by rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma enrolled onto the GELA-GOELAMS FL-2000 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):440–446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leek RD, Lewis CE, Whitehouse R, Greenall M, Clarke J, Harris AL. Association of macrophage infiltration with angiogenesis and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56(20):4625–4629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(6):717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee AM, Clear AJ, Calaminici M, et al. Number of CD4+ cells and location of forkhead box protein P3-positive cells in diagnostic follicular lymphoma tissue microarrays correlates with outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):5052–5059. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason DY, Micklem K, Jones M. Double immunofluorescence labelling of routinely processed paraffin sections. J Pathol. 2000;191(4):452–461. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH665>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Passalidou E, Stewart M, Trivella M, et al. Vascular patterns in reactive lymphoid tissue and in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(4):553–559. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podgrabinska S, Braun P, Velasco P, Kloos B, Pepper MS, Skobe M. Molecular characterization of lymphatic endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(24):16069–16074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242401399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buechler C, Ritter M, Orso E, Langmann T, Klucken J, Schmitz G. Regulation of scavenger receptor CD163 expression in human monocytes and macrophages by pro- and antiinflammatory stimuli. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67(1):97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leek RD, Landers RJ, Harris AL, Lewis CE. Necrosis correlates with high vascular density and focal macrophage infiltration in invasive carcinoma of the breast. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(5):991–995. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toge H, Inagaki T, Kojimoto Y, Shinka T, Hara I. Angiogenesis in renal cell carcinoma: the role of tumor-associated macrophages. Int J Urol. 2009;16(10):801–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shieh YS, Hung YJ, Hsieh CB, Chen JS, Chou KC, Liu SY. Tumor-associated macrophage correlated with angiogenesis and progression of mucoepidermoid carcinoma of salivary glands. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(3):751–760. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tjiu JW, Chen JS, Shun CT, et al. Tumor-associated macrophage-induced invasion and angiogenesis of human basal cell carcinoma cells by cyclooxygenase-2 induction. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(4):1016–1025. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lobov IB, Rao S, Carroll TJ, et al. WNT7b mediates macrophage-induced programmed cell death in patterning of the vasculature. Nature. 2005;437(7057):417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature03928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao S, Lobov IB, Vallance JE, et al. Obligatory participation of macrophages in an angiopoietin 2-mediated cell death switch. Development. 2007;134(24):4449–4458. doi: 10.1242/dev.012187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ojalvo LS, Whittaker CA, Condeelis JS, Pollard JW. Gene expression analysis of macrophages that facilitate tumor invasion supports a role for Wnt-signaling in mediating their activity in primary mammary tumors. J Immunol. 2010;184(2):702–712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klapper W, Hoster E, Rolver L, et al. Tumor sclerosis but not cell proliferation or malignancy grade is a prognostic marker in advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3330–3336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]