Abstract

β-Silyloxy-α-ketoesters are prepared through a cyanide-catalyzed benzoin-type reaction with silyl glyoxylates and aldehydes. The products undergo a dynamic kinetic resolution to provide enantioenriched orthogonally protected alcohols and can be converted to the corresponding β-silyloxy-α-aminoesters.

α-Ketoesters play an important role in organic synthesis1 and are prevalent substructures of many biologically active natural products such as 3-deoxy-D-manno-2-octulosonic acid (KDO), 3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galacto-2-nonulosonic acid (KDN), and N-acetylneuraminic acid.2 Due to inductive effects of the attached ester and opportunities for chelation, α-ketoesters exhibit dramatically enhanced electrophilicity relative to normal ketones.3 They react readily with nucleophiles to give tertiary α-hydroxy esters and undergo reduction4 and reductive amination5 to provide access to stereochemically defined α-hydroxy esters and α-amino esters, respectively.

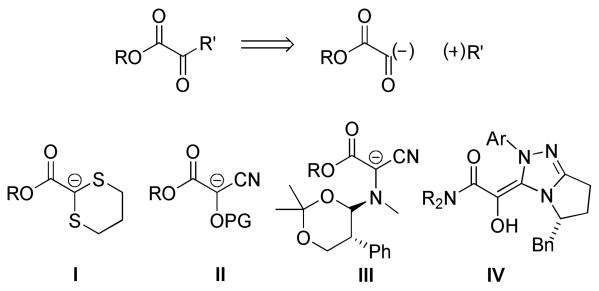

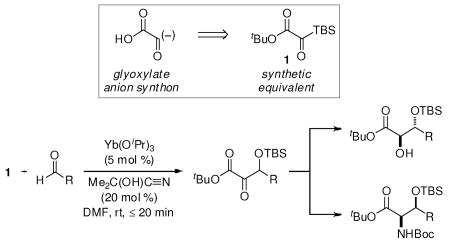

Although the α-ketoester is a highly versatile building block, its de novo introduction has not been generalized, particularly those α-ketoesters bearing a β-stereogenic center.6 Germane to the present work are several methodologies that have been developed to construct the α-keto acid derivative via electrophilic trapping of glyoxylate anion equivalents. Eliel demonstrated that 1,3-dithiane-2-lithio-2-carboxylates (I) undergo alkylation to provide 1,2-dicarbonyl compounds after deprotection,7 and Takahashi has utilized 2-metallo-2-alkoxy-2-cyanoacetates (II) in a related manner (Figure 1).8 Chiral glyoxylate anion equivalents have been reported by Enders, who used a chiral α-amino cyanoacetate (III),9 and Rovis, who employed glyoxyamides as the glyoxylate donor in a catalytic enantioselective Stetter reaction proceeding via the chiral acyl-Breslow intermediate IV.10 The purpose of this communication is to introduce silyl glyoxylates (1) as synthetic equivalents to the glyoxylate anion synthon in the context of carbonyl addition reactions.

Figure 1.

Glyxoylate anion synthetic equivalents

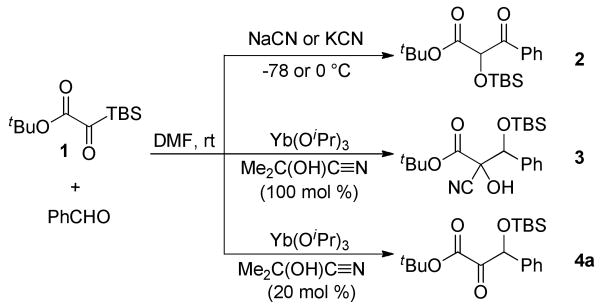

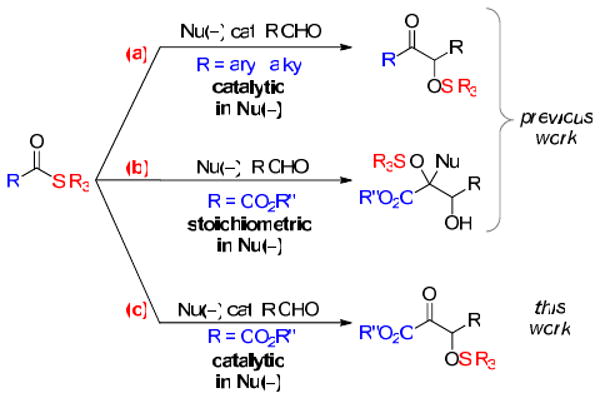

Acyl silanes11 have been developed as acyl anion equivalents for use in the racemic12 and enantioselective13 cross silyl benzoin reaction (Figure 2(a)). While broad in scope, it occurred to us that in certain instances carboxyl functionality adjacent to the ketone might be desirable and could significantly expand the product types delivered by this reaction type (Figure 2(c)). Silyl glyoxylates14 are related reagents that have proven useful for the geminal linking of nucleophile and electrophile pairs at a glycolic acid junction. A common reactivity pathway explored in our laboratory with silyl glyoxylates involves nucleophilic addition, 1,2-Brook rearrangement,15 and electrophilic trapping (Figure 2(b)).16 These multicomponent reactions are believed to proceed through glycolate enolate intermediates. Various examples incorporate the nucleophile as a stoichiometric component; however, we postulated that in the presence of a nucleophilic catalyst and aldehyde we could arrive at β-silyloxy-α-ketoesters via a silyl benzoin mechanism.12c,d Alternative methods for the preparation of the proposed product β-hydroxy-α-ketoacid derivatives include the addition of diazoacetates to aldehydes followed by oxidation17 and Baylis-Hilman reaction followed by alkene ozonolysis.18

Figure 2.

Comparison of acyl silane and silyl glyoxylate reactivity

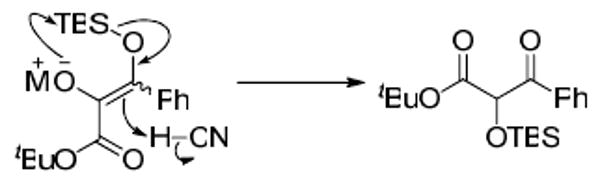

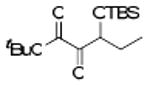

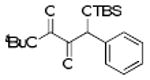

Preliminary studies focused on identifying a viable nucleophilic catalyst. We evaluated various metal cyanides with benzaldehyde as the test substrate (Scheme 1). Sodium cyanide, potassium cyanide and potassium cyanide/18-crown-6 complex were the initial metal cyanides screened. In each case, the desired ketone product was not obtained; instead, the reaction yielded the α-silyoxy-β-keto ester 2. This product is likely derived from isomerization of the initially formed α-ketoester under the basic reaction conditions (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1.

Optimization of Reaction Conditions with Metal Cyanides

Scheme 2.

Isomerization Pathway

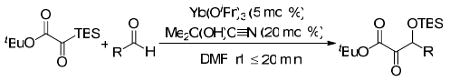

We sought to identify a less basic source of cyanide that could potentially stop at the desired ketone product. Lanthanide isopropoxides have been reported as efficient catalysts in the transhydrocyanation from acetone cyanohydrin to aldehydes and ketones.19 We were pleased to find that the combination of Yb(OiPr)3 (10 mol %) and acetone cyanohydrin (Me2C(OH)C≡N, 1 equiv) yielded the desired ketone product, albeit as the cyanohydrin adduct 3 (dr: 1.2:1). A catalytic amount of acetone cyanohydrin afforded the desired β-silyloxy-α-ketoester in 64% yield. Optimization of the reaction conditions revealed that the α-ketoester 4a could be obtained in up to 90% yield using 5 mol % Yb(OiPr)3, 20 mol % acetone cyanohydrin, and 2 equivalents of aldehyde.

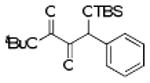

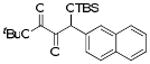

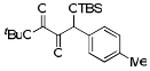

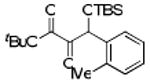

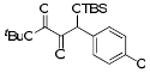

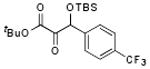

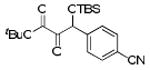

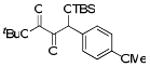

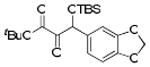

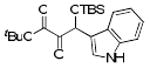

With optimized conditions in hand, we wished to examine the scope of the reaction (Table 1). Electron-rich, electron-poor, heteroaromatic, and aliphatic aldehydes all performed well in the reaction with yields ranging from 75 to 96%. The reaction has steric limitations as pivalaldehyde failed to provide any desired product. It is notable that all reactions were complete within twenty minutes, and in most cases the silyl glyoxylate was completely consumed immediately upon addition of all reagents (See Supporting Information). An attractive feature of this reaction is that the products can be obtained in analytically pure form after passing the crude reaction mixture through a short silica plug and removing the excess aldehyde under reduced pressure.

Table 1.

Scope of Aldehyde Glyoxylation

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | product | structure | yielda (%) |

| 1 | 4a |  |

87 |

| 2 | 4b |  |

92 |

| 3 | 4c |  |

80 |

| 4 | 4d |  |

86 |

| 5 | 4e |  |

89 |

| 6 | 4f |  |

90 |

| 7 | 4g |  |

92 |

| 8 | 4h |  |

85 |

| 9 | 4i |  |

86 |

| 10 | 4j |  |

88 |

| 11b | 4k |  |

96 |

| 12b | 4l |  |

85 |

Yields of analytically pure material after work-up.

Sm(OiPr)3 (10 mol %) was employed.

The title reaction appears amenable to enantioselective catalysis. When deuterated benzaldehyde (PhCDO) was used as the electrophile, full deuterium incorporation at the methine was observed in 4a-d1, suggesting that the product is stable toward enolization under the silyl benzoin conditions. The ideal chiral catalyst would need to both facilitate the transhydrocyanation and direct the facial selectivity in the subsequent aldehyde addition. Preliminary studies employing chiral metallocyanides20 yielded racemic material and reactions with chiral metallophosphites13,21 provided no desired product; however, due to the acidity of the α-ketoester, we thought our substrates would be good candidates to undergo a dynamic kinetic resolution delivering enantioenriched orthogonal diols (6, Table 2).

Table 2.

Dynamic Kinetic Resolution of 4a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | [H−]/base (equiv) | conv (%)a (6 : 2) | erb (anti) | drcanti:syn |

| 1 | HCOOH/NEt3 (3.2/4.4) | 88:12 | 67:33 | 5:1 |

| 2 | HCOOH/NEt3 (12.5/5.0) | 79:21 | 67:33 | 4:1 |

| 3 | HCOOH/NEt3 (3.2/10.0) | 35:65 | 78:22 | 4:1 |

| 4d | HCOONa (5.0) | 97:0 | 67:33 | 3:1 |

| 5e | HCOONa (5.0) | 93:7 | 71:29 | 3:1 |

| 6 | HCOONa (5.0) | 92:8 | 72:28 | 3:1 |

| 7 | HCOOH/DIEA (3.2/10.0) | 67:33 | 75:25 | 2:1 |

| 8 | HCOOH/Cs2CO3 (3.2/10.0) | 91:9 | 70:30 | 3:1 |

| 9 | HCOOH/Li2CO3 (3.2/10.0) | 73:27 | 70:30 | 3:1 |

| 10 | HCOOH/BaCO3 (3.2/10.0) | 46:2 | 70:30 | 3:1 |

| 11 | HCOOH/CdCO3 (3.2/10.0) | 51:5 | 76:24 | 3:1 |

| 12 | HCOOCs (5.0) | 89:6 | 70:30 | 3:1 |

Conversion determined by 1HNMR spectroscopy.

Enantiomeric excess determined by SFC.

Diastereomeric excess determined by 1HNMR spectroscopy.

Reaction run at 0 °C.

Reaction run at 40 °C.

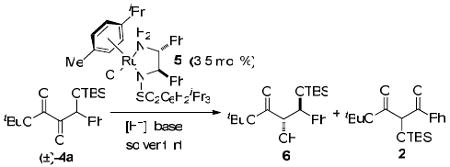

There are a number of examples of dynamic asymmetric (transfer) hydrogenations of benzoin-type substrates employing chiral ruthenium(II) complexes.22 We initially examined the use of Noyori-type conditions23 with BINAP-derived catalysts and 4a, but no reaction was observed. We attributed this lack of reactivity to the steric bulk of the TBS protected alcohol. Unfortunately, initial attempts to remove the silyl group led to decomposition, perhaps through retro-aldol reaction. We then turned our attention to using catalysts of the type 5 in an asymmetric transfer hydrogenation with triethylamine as the base and formic acid as the hydride source.24 The ketone was reduced under these conditions, albeit with low enantioselectivity and moderate anti-diasteroselectivity (Table 2, entry 1).

Increasing the equivalents of base led to higher enantioselectivities (entry 3), and this result can possibly be attributed to more rapid racemization of the starting material; however, these basic conditions also facilitated formation of the isomerized product 2. Interestingly, this ketone is not reduced under these reaction conditions. We then explored the use of sodium formate as the hydride source (entries 4-6) with the expectation that its decreased basicity would still be sufficient for racemization but would not facilitate silyl transfer. We were pleased to find that these conditions reduced 4a with only trace amounts of the isomerized product 2 at room temperature (entry 6), and at 0 °C silyl transfer is completely suppressed (entry 4). Unfortunately, under these conditions the er is diminished.

An assessment of other bases in combination with formic acid revealed that the degree of isomerization could be lowered (entries 7-11). However, the highest er observed was 76:24, with a dr of 3:1(entry 11). Future work will focus on: 1) increasing the rate of starting material racemization; 2) minimizing silyl transfer; and 3) fine-tuning the catalyst structure to achieve optimal enantio- and diasteroselectivity.

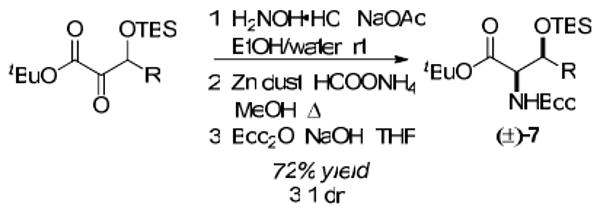

The α-ketoester products may also be converted to their derived β-silyloxy-α-aminoesters (i.e. 7, Scheme 3). Under standard reductive amination conditions, competitive ketone reduction was observed.25 The desired product was obtained from a three-step sequence (72% overall yield) consisting of conversion to the oxime, reduction, and Boc protection.26 Preference for the syn-diastereomer in a 3 : 1 ratio was observed.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of β-Silyoxy-α-aminoesters

In summary, we have developed a nucleophilic glyoxylation of aldehydes with silyl glyoxylates. The products are able to undergo a subsequent dynamic kinetic resolution, providing enantioenriched monoprotected diols with enantioselectivity up to 76:24 and diastereoselection up to 5:1. The glyoxylation products can be further elaborated to β-silyloxy-α-aminoesters, highlighting their potential as small-molecule building blocks. Future studies will focus on developing catalytic asymmetric glyoxylation and optimizing dynamic kinetic resolutions of racemic glyoxylation adducts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number R01 GM084927 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Novartis, and Amgen.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and analytical data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Cooper A, Meister GA. Chem Rev. 1983;83:321. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kovacs L. Rec Trav Chim PaysBas. 1993;112:471. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiefel MJ, von Itzstein M. Chem Rev. 2002;102:471. doi: 10.1021/cr000414a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans DA, Burgey CS, Kozlowski MC, Tregay SW. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:686. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao W, Wang J. Org Lett. 2003;5:1527. doi: 10.1021/ol0343257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang Q, Zhao ZA, You SL. Adv Synth Catal. 2007;349:1657. [Google Scholar]

- 6.For a recent example see: Nakamura A, Lectard S, Hashizume D, Hamashima Y, Sodeoka M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4036. doi: 10.1021/ja909457b.

- 7.Eliel E, Hartmann A. J Org Chem. 1972;37:505. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Takahashi T, Okano T, Harada T, Imamura K, Yamada H. Synlett. 1994;38:121. [Google Scholar]; (b) Takahashi T, Tsukamoto H, Kurosaki M, Yamada H. Synlett. 1997;41:1065. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Enders D, Bonten MH, Raabe G. Synlett. 2007;51:885. [Google Scholar]; (b) Enders D, Bonten MH, Raabe G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2314. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Q, Perreault S, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14066. doi: 10.1021/ja805680z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Degl'Innocenti A, Ricci A, Mordini A, Reginato G, Colotta V. Gazz Chim Ital. 1987;117:645. [Google Scholar]; (b) Reich HJ, Holtan RC, Bolm C. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5609. [Google Scholar]; (c) Takeda K, Ohnishi Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:4169. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Degl'Innocenti A, Pike S, Walton DRM. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1980:1201. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schinzer D, Heathcock CH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:1881. [Google Scholar]; (c) Linghu X, Johnson JS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:2534. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Linghu X, Bausch CC, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1833. doi: 10.1021/ja044086y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linghu X, Potnick JR, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3070. doi: 10.1021/ja0496468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicewicz DA, Brétéché G, Johnson JS. Org Synth. 2008;85:278. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brook AG. Acc Chem Res. 1974;7:77. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicewicz DA, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6170. doi: 10.1021/ja043884l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Linghu X, Satterfield AD, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9302. doi: 10.1021/ja062637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nicewicz DA, Satterfield AD, Schmitt DS, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17281. doi: 10.1021/ja808347q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Greszler SN, Johnson JS. Org Lett. 2009;11:827. doi: 10.1021/ol802828d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Greszler SN, Johnson JS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009:3689. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Schmitt DS, Johnson JS. Org Lett. 2010;12:944. doi: 10.1021/ol9029353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Yao W, Wang J. Org Lett. 2003;5:1527. doi: 10.1021/ol0343257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hasegawa K, Arai S, Nishida A. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:1390. [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM, Malhotra S, Fried BA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1674. doi: 10.1021/ja809181m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frezza M, Soulère L, Queneau Y, Doutheau A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:6495. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohno H, Mori A, Inoue S. Chem Lett. 1993:375. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Nicewicz DA, Yates CM, Johnson JS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2652. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicewicz DA, Yates CM, Johnson JS. J Org Chem. 2004;64:6548. doi: 10.1021/jo049164e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Nahm MR, Potnick JR, White PS, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2751. doi: 10.1021/ja056018x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Garrett MR, Tarr JC, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12944. doi: 10.1021/ja076095n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Ikariya T, Hashiguchi S, Murata K, Noyori R. Org Syn. 2005;82:10. [Google Scholar]; (b) Arai N, Ooka H, Azuma K, Yabuuchi T, Kurono N, Inoue T, Ohkuma T. Org Lett. 2007;9:939. doi: 10.1021/ol070125+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ooka H, Arai H, Azuma K, Kurono N, Ohkuma T. J Org Chem. 2008;73:9084. doi: 10.1021/jo801863q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandoval CA, Ohkuma T, Muniz K, Noyori R. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13490. doi: 10.1021/ja030272c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikariya T, Blacker J. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:1300. doi: 10.1021/ar700134q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdel-Magid AF, Mehrman SJ. Org Process Res Dev. 2006;10:971. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Abiraj K, Gowda DC. J Chem Res. 2003;6:332. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hasegawa K, Arai S, Nishida A. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:1390. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.