Abstract

West Nile virus is similar to most other RNA viruses in that it exists in nature as a genetically diverse population. However, the role of this genetic diversity within natural transmission cycles and its importance to virus perpetuation remains poorly understood. Therefore, we determined whether highly genetically diverse populations are more fit compared to less genetically diverse WNV populations. Specifically, we generated three WNV populations that varied in their genetic diversity and evaluated their fitness relative to genetically marked control WNV in vivo in Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes and chickens. Our results demonstrate that high genetic diversity leads to fitness gains in vector mosquitoes, but not chickens.

Keywords: West Nile virus, Flavivirus, Arbovirus, Fitness, Quasispecies, Mosquitoes

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV, Flaviviridae:Flavivirus) perpetuates in nature in a transmission cycle involving ornithophilic mosquitoes, mainly Culex spp. and birds(Komar, 2000). In the decade since it was first recognized in North America(Lanciotti et al., 1999), WNV has spread and become well established throughout much of the New World, where it causes seasonal epidemics of fever and encephalitis in humans and domestic and wild animals. Like other RNA viruses, WNV exists in its natural transmission cycle as a closely related group of competing viral mutants commonly referred to as a quasispecies(Jerzak et al., 2005). Field-based studies have shown that WNV is genetically diverse within infected mosquitoes and birds, that a genetically diverse population is transmitted between hosts, and that WNV populations within mosquitoes are more diverse than are those in birds(Jerzak et al., 2005). Laboratory-based studies have confirmed that genetic diversity is higher within mosquitoes(Jerzak et al., 2007) and suggest that RNA interference (RNAi) drives genetic diversification within these hosts by creating an intracellular milieu that is favorable to rare virus genotypes(Brackney et al., 2009). A relatively high level of genetic diversity, particularly within mosquitoes, seems to be a general feature of WNV population structure.

RNA virus replication is characterized by an ongoing, continual process that includes the creation of novel mutants and competition between newly arising and previously existing genotypes. Virus fitness represents the ability of a particular genotype to contribute to subsequent generations, i.e., its relative ability to survive and reproduce in a particular environment and/or host population. Several studies have examined fitness determinants of arboviruses, including passage history in various cell culture or animal models(Ciota et al., 2006; Martinez et al., 1991; Taylor & Marshall, 1975; Weaver et al., 1999; Coffey et al., 2008) and specific genetic determinants that impact, for example, production of viremia or thermal stability(Brault et al., 2002; Brault et al., 2007). Comparative studies have demonstrated that the originally introduced WNV genotype (NY99) has been displaced by a new North American adapted genotype (WN02). It was determined that this displacement was due to a decrease in the extrinsic incubation period in mosquitoes required for WN02 transmission compared to the NY99 genotype(Ebel et al., 2004; Moudy et al., 2007). In addition, competitive fitness studies using a monoclonal antibody resistant WNV mutant have suggested that passage in various cell culture systems can alter the fitness of the passed virus relative to the unpassed parental virus(Ciota et al., 2006). However, none of these studies have examined the role of intrahost genetic diversity on virus fitness directly. This is somewhat surprising since WNV populations are relatively genetically diverse. Furthermore, most competitive fitness studies of WNV and most other arboviruses have measured virus fitness in cell cultures that may poorly simulate those organisms most relevant to arbovirus fitness in natural transmission cycles (with some notable exceptions(Coffey et al., 2008)). Therefore, it is currently not clear whether the high genetic diversity that is characteristic of WNV populations impacts fitness in vivo, or in any way contributes to its ability to persist in nature.

Accordingly, we evaluated the hypothesis that the genetic diversity of WNV within infected hosts influences virus fitness. In particular, we sought to determine whether WNV populations with higher genetic diversity would be (a) more infectious to chickens or mosquitoes or (b) more fit in these hosts. To accomplish this, we engineered a genetically marked control WNV to serve as a competitor in fitness studies, evaluated its phenotype relative to unmarked WNV and developed methods for measuring its relative frequency in a genetically mixed WNV population. Next, WNV populations that contained varying levels of genetic diversity were created and their phenotype was evaluated in comparative infectivity studies in Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus mosquitoes and young chickens (Gallus gallus). Finally, we assessed the fitness of WNV populations of varying genetic diversity in vivo relative to the marked competitor.

Results

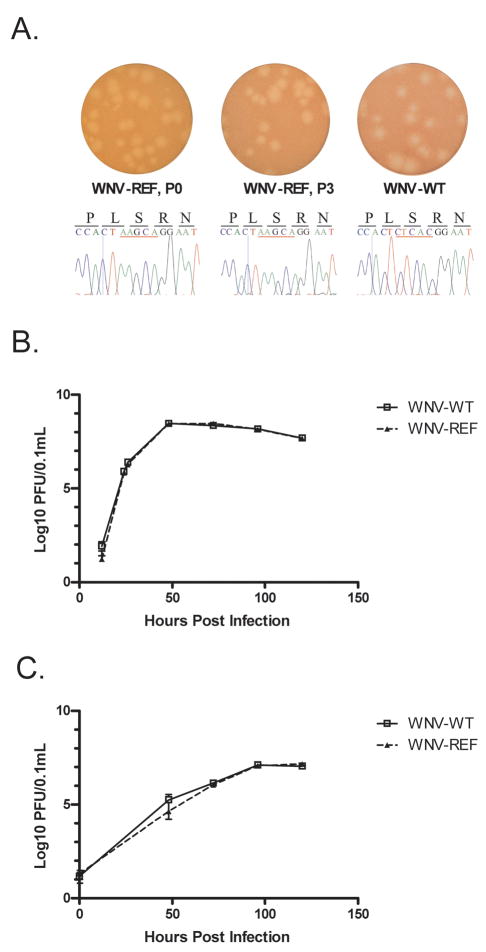

Characterization of Marked Reference virus

A genetically marked reference virus for use in competitive fitness studies was produced by inserting a string of five noncoding changes into nucleotide positions 8313–8317 of a WNV cDNA clone. Plaque phenotype and replication kinetics of marked reference virus (WNV-REF) was compared to unmarked virus (WNV-WT) and the stability of the marker was evaluated. WNV-REF and WNV-WT demonstrated similar replication kinetics in Vero and C6/36 cells, and plaque size was similar (Figure 1). Furthermore, no reversion mutations were detected after three blind passages in Vero cells.

Figure 1. Genetically marked reference is phenotypically indistinguishable from unmarked WNV.

Plaque phenotype of WNV-REF and unmarked clone-derived WNV (A) and replication in Vero (B) and C6/36 cells (C) was compared. Plaque phenotype and reversion of the genetic markers in WNV-REF was evaluated after three blind passages on Vero cells (Panel A). No differences were detected in plaque phenotype or in vitro replication, and no reversions were detected in the genetic marker.

Characterization of Mixed Virus Populations

We created genetically diverse viruses by mixing either 2, 8 or 24 individual strains and amplifying them in cell culture. The resulting WNV populations, M2, M8 and M24, were characterized genetically by cloning and sequencing. Either 19 or 20 clones per virus population were sequenced. M24 was the most genetically diverse population, followed by M8 and M2 with respect to both haplotypes and overall genetic diversity (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis (Supplement and Figure S1) of clones obtained from each virus population indicated two main haplotypes for M2 and increasingly greater numbers for M8 and M24. All three mixed virus populations were similar in their infectiousness to chickens and mosquitoes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mixed WNV populations

| WNV Strain | Titera | Number of: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clones Sequenced | Haplotypes | Mutations | NT sequenced | Genetic diversity (%) | ||

| M2 | 6.50E+07 | 20 | 6 | 11 | 39,117 | 0.028 |

| M8 | 6.50E+07 | 19 | 12 | 28 | 36,219 | 0.077 |

| M24 | 1.35E+06 | 18 | 14 | 41 | 35,274 | 0.116 |

| P valueb | >0.01 | |||||

PFU Per 0.1mL

Chi-square = 417.0, 2df

Table 2.

Infectivity of WNV populations.

| WNV Strain | ID50a for: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Chickens | Mosquitoes | |

| M2 | 0.016 | 1.9E+05 |

| M8 | 0.032 | 2.6E+05 |

| M24 | 0.032 | 1.0E+05 |

Values are given in PFU.

Vector Competence of Cx. quinquefasciatus for mixed virus populations

Fitness was initially assessed through examination of the ability of M2, M8 and M24 to infect, disseminate within and be transmitted by Cx. quinquefasciatus. At both seven and fourteen days postfeeding, mosquitoes that fed on M2 were the least likely, and those that fed on M24 were the most likely to have infectious WNV in their bodies (Table 3). Dissemination and transmission also appeared to occur more frequently in mosquitoes that had been fed M24, but relatively few mosquitoes developed disseminated or transmitted infections in these studies (Table 3) and the trend was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Impact of WNV population diversity on mosquito transmission phenotype

| Strain | Days Post Feeding: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 |

14 |

|||||

| Percent: |

Percent: |

|||||

| Infected(n) | Disseminated | Transmitted | Infected(n) | Disseminated | Transmitted | |

| M2 | 30 (47) | 2 | 0 | 37 (43) | 7 | 5 |

| M8 | 47 (47) | 2 | 0 | 40 (47) | 6 | 2 |

| M24 | 51 (47) | 6 | 2 | 68 (47) | 15 | 4 |

| Pa | 0.0370 | >0.05 | >0.05 | 0.0030 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

Chi-square test for trend

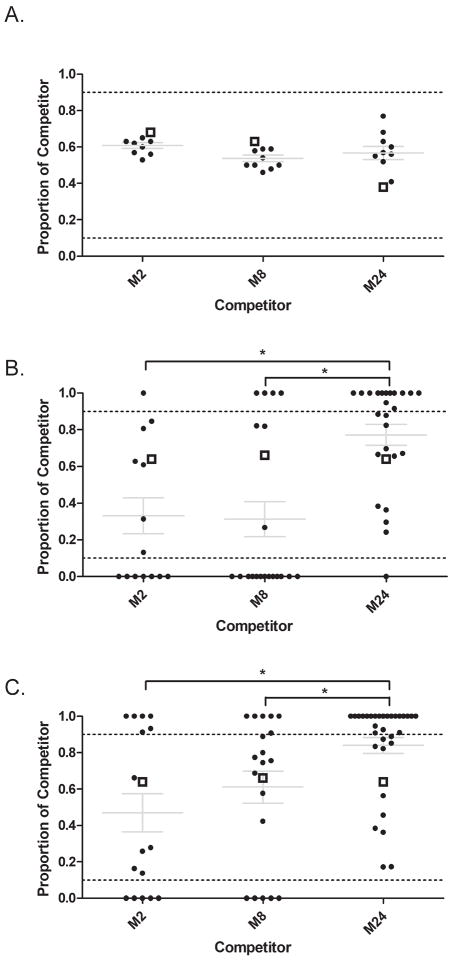

Competitive fitness of mixed virus populations

The fitness of M2, M8 and M24 in orally infected mosquitoes and subcutaneously inoculated chickens was determined by quantitative sequencing. The range for sequencing to estimate the proportion of each genotype in any given sample under the described conditions was from approximately 0.1–0.9 (supplementary information and data not shown). After 48 hours of replication in chickens, the proportion of WNV-REF and all three competitors was similar, with approximately 50% of total virus in mosquito bodies comprising the competitor (M2, etc.) genotype (Figure 2). In addition, the mean proportion of each competitor was generally similar to that present in the inoculum. After seven and fourteen days replication in mosquitoes, the mean proportion of each competitor was variable, ranging from approximately 35 to ~80 percent. At both timepoints post feeding, M24 comprised a higher proportion of the WNV in mosquito bodies than did M2 and M8 (Day 7: Kruskall-Wallis P=0.0001, Dunn’s Multiple Comparison Test P<0.05 for M2 vs. M24 and M8 vs. M24; Day 14: Kruskall-Wallis P=0.0044, Dunn’s MCT P<0.05 for M2 vs. M24 and M8 vs. M24), and an increasing trend in the means was apparent after fourteen days in mosquitoes.

Figure 2. Increased genetic diversity is associated with increased fitness in mosquitoes but not chickens.

Fitness was evaluated in competition studies using M2, M8 and M24 mixed 1:1 with WNV-REF after 48 hours in chickens (A) and after seven (B) and fourteen (C) days extrinsic incubation in mosquitoes. Points indicate individual mosquitoes. Open squares denote the proportion of each competitor present in the starting virus pool determined either by sampling the inoculum used for chickens (A) or by sampling freshly engorged mosquitoes (B and C). Bars indicate the mean and standard error for each competition. Asterisks indicate statistically significant results.

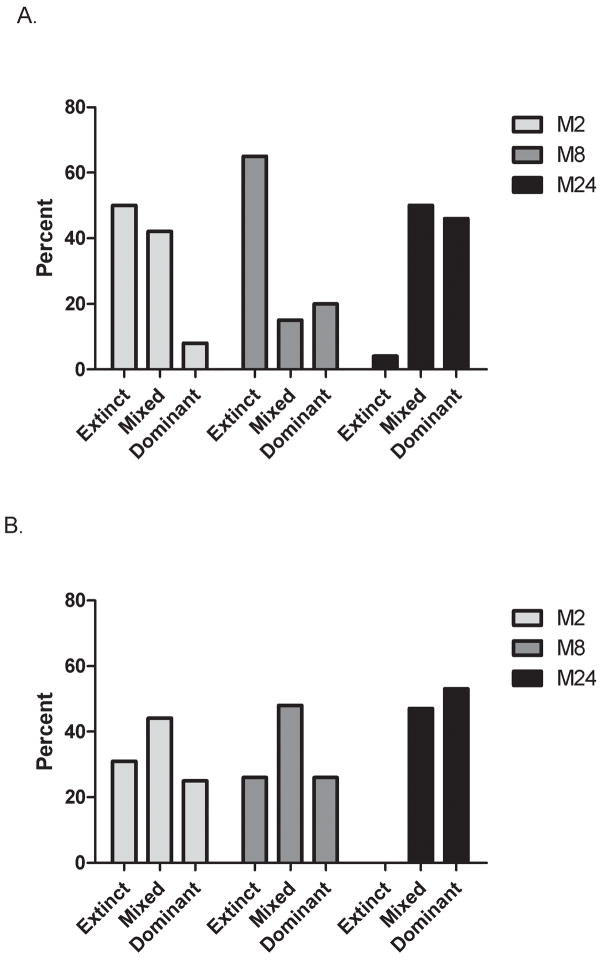

In mosquitoes, however, the proportion of each competitor in individual mosquito bodies varied widely, with several individuals containing only one or the other genotype. Therefore, the likelihood that a competitor virus would either become dominant (representing 100% of the virus detected in a sample) or go extinct (representing 0%) was examined (Figure 3). The makeup of WNV in mosquitoes where WNV was dominant was variable (Supplemental Information). The proportion of individual mosquitoes where M24 went extinct was lower in both cohorts examined than the proportion of mosquitoes where M2 and M8 went extinct. Further, M24 was more likely than M2 or M8 to become dominant and completely displace WNV-REF in mosquito bodies (Chi-squared P<0.05 at both 7 and 14 days post feeding).

Figure 3. More genetically diverse WNV populations are less likely to go extinct and more likely to become dominant.

The virus population from individual mosquitoes were classified according to the relative success of the competitor after seven (A) and fourteen (B) days extrinsic incubation. Bars marked “extinct” in the figure represent the percent of mosquitoes where only the reference genotype (WNV-REF.) was detected. Bars marked “dominant” in the figure represent the percent of mosquitoes where only the competitor genotype (M2, etc.) was detected. Bars marked “mixed” represent the percent of mosquitoes where both competitor and reference genotypes were detected. Linear range of detection (0.1-0.9) is shown by dotted lines. For day 7, Chi-squared = 17.84, df = 4, P = 0.0013. For day 14, Chi-squared = 12.79, df = 4, P = 0.0124.

Discussion

Several studies to date have analyzed fitness of WNV and other viruses using monoclonal antibody escape mutant (MARM) viruses(Ciota et al., 2006; Martinez et al., 1991; Ruiz-Jarabo et al., 2002). In order to avoid the potential for fundamentally altering important biological characteristics of the virus (i.e. attachment and entry) that may be dependent on the properties of an antigenic surface protein, we marked a reference competitor virus genetically by inserting a string of five consecutive synonymous mutations into the NS5 methyltransferase coding sequence. We characterized WNV-REF in various model systems to rule out the possibility that the genetic marker was (a) unstable and/or (b) would somehow interfere with the replication kinetics of the virus. First, blind passage of WNV-REF three times on Vero cells failed to yield any reversion mutations, indicating high stability of the marker and suggesting that it did not alter the methyltransferase function. Plaque size of WNV-REF and the parental WNV-WT viruses were similar, also suggesting that they replicated with approximately equal efficiency. We then evaluated replication directly in Vero and C6/36 cells. Both WNV-REF and WNV-WT showed nearly identical replication kinetics in these culture systems.

Next, we created and characterized WNV populations of varying genetic diversity to facilitate studies of the impact of WNV genetic diversity on virus fitness. We created populations that had low (M2) medium (M8) and high (M24) genetic diversity. We observed six haplotypes in our M2 population and 12 in M8, suggesting that point mutations occurred to the main genotypes that were used to create them. However, both the number of haplotypes and the overall genetic diversity was lowest in M2 and highest in M24. Previously, we estimated the levels of genetic diversity in field collected mosquitoes and birds. These studies found that in nature, WNV populations within hosts posses at most 0.065 nucleotide and 45% haplotype diversity. Therefore, according to mutational and haplotype diversity, M2 is similar to an average field-collected WNV population, M8 is similar to the most diverse population, and M24 is more diverse than any population observed in nature. WNV-REF was created from an infectious cDNA clone and was used without further passage. The mutational diversity of this virus population was assumed to be essentially zero, as observed previously for virus produced from the same clone in an identical manner(Jerzak et al., 2005). Collectively, these observations permit us to conclude that the viruses we created (WNV-REF, M2, M8 and M24) represent appropriate set of tools to evaluate the role of mutational diversity on virus fitness.

An important component of the fitness of any virus is its infectiousness for relevant hosts. Accordingly, we tested the infectivity of mixed virus populations in mosquitoes and chickens. We observed ID50s in both mosquitoes infected by the oral route and chickens inoculated by the SC route that were essentially identical. In both cases, these results suggest that viral genetic diversity does not influence infectivity in the WNV system used in these experiments.

We then evaluated competitive fitness in chickens and mosquitoes by infecting each host with approximately 1:1 ratios of WNV-REF and various mixed WNV populations. In chickens we observed only minor differences in the competitive fitness of test virus populations compared to WNV-REF at the time of peak viremia: 48 hours post inoculation. Analysis of earlier and later timepoints or specific tissues from infected animals might have revealed differences that occurred either very early or vary late in infection. However, the timepoint we assessed in this study represents the most relevant timepoint from the perspective of virus transmission and likely accurately reflects the fitness implications of intrahost genetic diversity in birds in nature. Our results in chickens suggest, moreover, that a highly genetically diverse population does not possess a significant fitness advantage over less diverse populations in chickens in vivo.

Our results in mosquitoes were strikingly different. We first analyzed our data on infection in terms of vector competence. At both seven and fourteen days post feeding, mosquitoes fed on more genetically diverse WNV were more likely to be infected compared to those fed on a less genetically diverse WNV. This result was surprising since we saw no differences in oral ID50 of each virus population, and suggests that our approach to determining the ID50s in these hosts was not sensitive enough to detect subtle differences in infectivity. A dose-response was also observed at both timepoints, with progressive gains in the proportion of infected mosquitoes associated with progressive increases in WNV genetic diversity. Finally, mosquitoes that fed on more genetically diverse WNV seemed to be more likely to develop disseminated or transmitted infections; however, relatively few mosquitoes overall fit into either of these categories. The relatively low levels of dissemination and transmission may be related to the low bloodmeal titer: In order to standardize the titer in M2, M8 and M24, all viruses were diluted to match the least concentrated stock. Robust analysis of the influence of genetic diversity on virus dissemination and transmission in mosquitoes requires further study. In any case, our data support the hypothesis that high WNV genetic diversity is associated with more efficient infection of mosquitoes.

Our results on the competitive fitness of M2, M8 and M24 support this observation. At both seven and fourteen days post feeding, M24 represented a higher proportion of the WNV in mosquitoes, on average, than did M2 or M8. At fourteen days post feeding, the fitness of mixed virus populations increased in a stepwise fashion with increasing genetic diversity. Therefore, increasing WNV genetic diversity is associated with increasing fitness in mosquitoes. Examination of Figure 2, however, clearly shows that in mosquitoes almost none of the observations fall close to the mean proportion, or within one standard error of the mean. Therefore, we determined the proportion of mosquitoes fed on each WNV population in which apparent displacement occurred (i.e. where M2, M8 and M24 represented either 0 or 100 percent of the estimated total population in the mosquito body). In this analysis, the most genetically diverse population, M24, seemed to avoid “extinction” and was more likely to become dominant than other populations. Thus, more genetically diverse WNV populations possess higher fitness in mosquito bodies than those of lower genetic diversity. Importantly, our method for estimating population frequency based on sequence chromatograms is relatively insensitive when one or the other genotype represents less than ~10% of the total population. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the “extinct” genotype persists as a relatively small fraction of the population of WNV in mosquito bodies and escapes our detection. Determining whether this is frequently the case requires more detailed examination (i.e. by cloning and/or deep sequencing) of individual mosquito bodies. However, based on our previous studies of WNV population variation in mosquitoes(Jerzak et al., 2005; Jerzak et al., 2007), this seems likely.

Overall, our results demonstrate a mosquito-specific fitness advantage of mutational diversity in WNV. This finding is consistent with previous studies that determined that in nature WNV genetic diversity is higher in mosquitoes than in birds(Jerzak et al., 2005) and that passage of WNV in mosquitoes results in higher genetic diversity than passage in chickens(Jerzak et al., 2007). Similar results were obtained by others working in cell culture systems(Ciota et al., 2006). Our findings are also consistent with our studies of RNA interference (RNAi) in mosquitoes(Brackney et al., 2009). These studies demonstrated that intense RNAi targeting of particular regions of the WNV genome was associated with increased mutational diversity in these regions relative to more weakly targeted regions. We hypothesized that RNAi in mosquitoes creates an intracellular environment that favors less common viral genotypes. It follows that a more complex virus population presents a more complicated target to the mosquito RNAi machinery. Our data demonstrating a fitness advantage of high genetic diversity in mosquitoes, where RNAi is a main antivirus response (Campbell et al., 2008; Myles et al., 2008; Brackney et al., 2009), but not in chickens is consistent with this hypothesis. Moreover, for some years it has been clear that high intrahost genetic diversity is associated with mosquitoes, but its role in the transmission of WNV or its evolutionary significance has been unclear. This study demonstrates for the first time that the intrinsic genetic diversity of an arbovirus population confers a fitness advantage in vivo in mosquitoes.

Materials and Methods

Cells and viruses

Monolayer cultures of Baby Hamster Kidney (BHK, ATCC CCL-10), African green monkey kidney (Vero, ATCC CCL-81) and Aedes albopictus (C6/36, ATCC CRL-1660) cells were grown according to standard procedures. Briefly, Vero and BHK cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Eagle’s minimal essential media (MEM) with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). C6/36 cells were grown at 28°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modification of Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS.

All viruses were either generated from an infectious cDNA clone as described elsewhere(Shi et al., 2002) or obtained from field-collected materials. To produce a genetically marked reference virus for fitness studies, a string of five noncoding changes were inserted into nucleotide positions 8313–8317 of a WNV cDNA clone such that the parental sequence CTC TCA CGG was changed to CTa agc aGG using site-directed mutagenesis according to procedures described elsewhere(Lo et al., 2003). The stability of the mutations was verified by sequencing the virus after three passages on Vero cells. Both wild-type WNV and genetically marked reference (WNV-REF) virus stocks were harvested from BHK cells after RNA electroporation without further passage in cell culture, and the titer was determined by plaque assay on Vero cells according to standard methods(Lindsey et al., 1976).

WNV populations of defined genetic diversity were created from field-collected strains. Viruses were initially isolated by inoculating homogenates of avian tissue or mosquitoes onto confluent Vero monolayers. Cells were monitored daily and when cytopathic effects were noted (generally 3–5 days post inoculation) tissue culture supernatants were harvested and stored at −80°C with 20% FBS in 0.5mL aliquots. Primary virus isolates were then amplified by a single passage on C6/36 cells and tissue culture supernatants harvested as above. The titer of C6/36-passed virus was then determined by plaque assay, and either 2, 8, or 24 individual strains were mixed such that equal plaque-forming units (PFU) of each strain were included in a single virus mixture, which was inoculated onto monolayers at a total multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. WNV strains were assembled in a “nested” design such that the more genetically diverse populations contained the strains used in those with less genetic diversity. These mixtures were subsequently amplified again on C6/36 cells and the supernatant harvested after seven days, brought to 20% FBS, aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use. These virus populations were designated M2 (two individual WNV strains), M8 (eight individual WNV strains) and M24 (24 individual WNV strains).

The genetic diversity of M2, M8 and M24 were quantified according to methods described previously(Jerzak et al., 2005). Briefly, a high-fidelity RT-PCR protocol was used to amplify an ~2kb region spanning the E and NS1 coding sequences. Amplicons were then cloned, and approximately 20 clones per WNV population sequenced. Genetic diversity was calculated and background error rate associated with our RT-PCR and cloning procedure was determined as described previously(Jerzak et al., 2005).

Experimental hosts

Fertile specific pathogen-free eggs (Charles River SPAFAS, North Franklin, CT) were incubated at 37.5°C with 67% humidity for 19 days with regular turning. After hatching on day 21 chicks were allowed to dry for 24 hours before being moved to brooders in the animal bio-safety level 3 (ABSL-3) facility. Chicks were provided with chicken feed and brooders were maintained at approximately 38°C. In all studies, chickens were inoculated at one day old by the subcutaneous route in the cervical region with 0.1 mL of WNV in animal inoculation diluent (endotoxin- and cation- free PBS with 1% FBS). Blood was collected into a capillary tube at the time of peak viremia (48 hours post inoculation) by puncturing the brachial vein and serum separated. Infection of chicks was detected by RT-PCR on serum according to methods described elsewhere(Shi et al., 2001).

Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus mosquitoes were maintained within a BSL3 insectary at 27°C on a 16:8 L:D photoperiod according to methods described elsewhere(Brackney et al., 2009). Mosquitoes in these studies were used at 6–7 days post-emergence. Prior to virus exposure, female mosquitoes were housed in quart sized containers and deprived of sucrose for 24 hours. Oral infections were established by allowing mosquitoes to feed on artificial bloodmeals containing defibrinated goose blood (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) containing WNV using a Hemotek membrane feeding apparatus (Accrington, UK). After one hour of feeding, engorged mosquitoes were removed to separate cups and held for either seven or fourteen days extrinsic incubation as described above. After extrinsic incubation, mosquito bodies, legs and salivary secretions were collected and mosquito tissues and salivary secretions processed as described elsewhere(Aitken, 1977; Ebel et al., 2004). Infection was detected by plaque assay on Vero cells.

Virus infectivity in chickens and mosquitoes

The virus dose that produced infection in 50% of chickens (ID50) was determined essentially as described in a previous publication(Jerzak et al., 2007). Briefly, groups of five or six one-day-old chicks were inoculated subcutaneously (SC) with serial tenfold dilutions of each virus as above. At two days post-inoculation blood was collected, also as above. Viral RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc, Valencia CA) and one-step RT-PCR was performed using the SuperScript III kit with platinum Taq (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA). Animals whose serum yielded a positive PCR result were considered to have become infected and the ID50 for each virus population was calculated according to the Reed and Muench method.

The oral ID50 of M2, M8 and M24 for mosquitoes was determined by feeding groups of female mosquitoes on serial tenfold dilutions of each virus in a bloodmeal as described above. After fourteen days extrinsic incubation whole mosquitoes were collected into 1mL of mosquito diluent (20% heat-inactivated FBS in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline plus 50ug/mL penicillin/streptomycin, 50ug/mL gentamicin and 2.5ug/mL fungizone) and homogenized. Infection was detected by plaque assay on Vero cells and the ID50 calculated also as above.

Fitness competitions

Mosquitoes were fed on bloodmeals containing 1:1 mixtures of test viruses (M2, M8 and M24) and marked reference virus (WNV-REF) according to methods described above. Final virus concentration in bloodmeals was approximately 3×106 PFU/0.1mL in all cases. Engorged females were separated under cold anesthesia and held for seven or fourteen days extrinsic incubation. 100ul of the virus-containing bloodmeal was collected to establish the proportion of test and control viruses in the offered bloodmeal. In addition, 4 fed mosquitoes were immediately removed to a 2.0mL microcentrifuge tube containing 1.0 mL of mosquito diluent to determine whether the proportion of test and control viruses ingested by feeding mosquitoes matched the proportions in the bloodmeal. At 7 and 14 days post feeding, mosquitoes were anaesthetized with triethyamine (Sigma, St. Louis MO) and in vitro transmission assays were performed as described elsewhere(Aitken, 1977) and above. Bodies, legs and salivary secretions were assayed for infection by plaque assay on Vero cells. Infection, dissemination and transmission were defined as the proportion of mosquitoes with infectious WNV in bodies, legs, and salivary secretions, respectively. For WNV competitions in chicks, equal titers of the reference and experimental viruses were mixed in animal inoculation diluent and approximately 2000 PFU were inoculated SC as above. Each competition group consisted of 8–11 chicks. Blood and tissue samples were obtained as described above.

The proportion of test and reference virus in each sample was determined by quantitative sequencing(Hall & Little, 2007). RNA was extracted from mosquito tissues that were positive by plaque assay and from all chicken samples using spin columns (QIAamp Viral RNA kit, Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Reverse transcription and PCR was performed using the One Step PCR kit (Qiagen) following standard protocol with primers designed to amplify the region containing the genetic marker [forward primer (5′-GCTCTGCCCCTACATGCCGAAAGT-3′); reverse primer (5′-TACTTCACTCCTTCTGGCGGTTCA-3′)] and the following thermocycling conditions: 50°C for 30 minutes, 95°C for 15 minutes, 40 cycles (94°C for 30 minutes, 60°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute), 72°C for 10 minutes. Products were purified using the StrataPrep PCR Purification Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Capillary sequencing was performed at the UNM Health Sciences Center DNA Research Services core facility.

Sequence chromatograms were analyzed using polySNP(Hall & Little, 2007). (http://staging.nybg.org/polySNP.html). Briefly, polySNP calculated the proportion of each genotype at the five nucleotide sites mutated in the marked reference virus by determining the area under the curve for each fluorescent dye at each variant chromatogram position. Thus, proportions of unmarked and marked reference nucleotides were quantitatively determined for each of the 5 sites from positions 8313–8317. The median value of these five estimates was adopted as the genotype proportion for each sample. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad software package.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Damon Little for generous assistance in implementing PolySNP, Laura Kramer for helpful comments on the manuscript, and Ivy K. Brown and Robert Nofchissey for valuable technical assistance. Animal experiments were approved by the University of New Mexico Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Sequencing was performed at the UNM DNA research Facility. This work was supported in part by funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institute of Health, under grant AI067380.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Aitken THG. An in vitro feeding technique for artifically demonstrating virus transmission by mosquitoes. Mosquito News. 1977;37:130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Brackney DE, Beane JE, Ebel GD. RNAi targeting of West Nile virus in mosquito midguts promotes virus diversification. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000502. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault AC, Huang CY, Langevin SA, Kinney RM, Bowen RA, Ramey WN, Panella NA, Holmes EC, Powers AM, Miller BR. A single positively selected West Nile viral mutation confers increased virogenesis in American crows. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/ng2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault AC, Powers AM, Holmes EC, Woelk CH, Weaver SC. Positively charged amino acid substitutions in the e2 envelope glycoprotein are associated with the emergence of venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:1718–1730. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1718-1730.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CL, Keene KM, Brackney DE, Olson KE, Blair CD, Wilusz J, Foy BD. Aedes aegypti uses RNA interference in defense against Sindbis virus infection. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciota AT, Lovelace AO, Ngo KA, Le AN, Maffei JG, Franke MA, Payne AF, Jones SA, Kauffman EB, Kramer LD. Cell-specific adaptation of two flaviviruses following serial passage in mosquito cell culture. Virology. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey LL, Vasilakis N, Brault AC, Powers AM, Tripet F, Weaver SC. Arbovirus evolution in vivo is constrained by host alternation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6970–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712130105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebel GD, Carricaburu J, Young D, Bernard KA, Kramer LD. Genetic and phenotypic variation of West Nile virus in New York, 2000–2003. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GS, Little DP. Relative quantitation of virus population size in mixed genotype infections using sequencing chromatograms. J Virol Methods. 2007;146:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerzak G, Bernard KA, Kramer LD, Ebel GD. Genetic variation in West Nile virus from naturally infected mosquitoes and birds suggests quasispecies structure and strong purifying selection. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2175–2183. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81015-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerzak GVS, Bernard K, Kramer LD, Shi PY, Ebel GD. The West Nile virus-mutant spectrum is host-dependant and a determinant of mortality in mice. Virology. 2007;360:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komar N. West Nile Viral Encephalitis. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epiz. 2000;19:166–176. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.1.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanciotti RS, Roehrig JT, Deubel V, Smith J, Parker M, Steele K, Crise B, Volpe KE, Crabtree MB, Scherret JH, Hall RA, MacKenzie JS, Cropp CB, Panigrahy B, Ostlund E, Schmitt B, Malkinson M, Banet C, Weissman J, Komar N, Savage HM, Stone W, McNamara T, Gubler DJ. Origin of the West Nile virus responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in the northeastern United States. Science. 1999;286:2333–2337. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey HS, Calisher CH, Matthews JH. Serum dilution neutralization test for California group virus identification and serology. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1976;4:503–510. doi: 10.1128/jcm.4.6.503-510.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo MK, Tilgner M, Bernard KA, Shi PY. Functional analysis of mosquito-borne flavivirus conserved sequence elements within 3′ untranslated region of West Nile virus by use of a reporting replicon that differentiates between viral translation and RNA replication. J Virol. 2003;77:10004–10014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.10004-10014.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez MA, Carrillo C, Gonzalez-Candelas F, Moya A, Domingo E, Sobrino F. Fitness alteration of foot-and-mouth disease virus mutants: measurement of adaptability of viral quasispecies. J Virol. 1991;65:3954–3957. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3954-3957.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudy RM, Meola MA, Morin LL, Ebel GD, Kramer LD. A newly emergent genotype of West Nile virus is transmitted earlier and more efficiently by Culex mosquitoes. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;77:365–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles KM, Wiley MR, Morazzani EM, Adelman ZN. Alphavirus-derived small RNAs modulate pathogenesis in disease vector mosquitoes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:19938–19943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803408105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Jarabo CM, Arias A, Molina-Paris C, Briones C, Baranowski E, Escarmis C, Domingo E. Duration and fitness dependence of quasispecies memory. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:285–296. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi PY, Kauffman EB, Ren P, Felton A, Tai JH, Dupuis AP, Jones SA, Ngo KA, Nicholas DC, Maffei J, Ebel GD, Bernard KA, Kramer LD. High-Throughput Detection of West Nile Virus RNA. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2001;39:1264–1271. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1264-1271.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi PY, Tilgner M, Lo MK, Kent KA, Bernard KA. Infectious cDNA clone of the epidemic west nile virus from New York City. J Virol. 2002;76:5847–5856. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5847-5856.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WP, Marshall ID. Adaptation studies with Ross River virus: retention of field level virulence. J Gen Virol. 1975;28:73–83. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-28-1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Brault AC, Kang W, Holland JJ. Genetic and fitness changes accompanying adaptation of an arbovirus to vertebrate and invertebrate cells. J Virol. 1999;73:4316–4326. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4316-4326.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.