Abstract

Men and women often disagree about the meaning of women's nonverbal cues, particularly those conveying dating-relevant information. Men perceive more sexual intent in women's behavior than women perceive or report intending to convey. Although this finding has been attributed to gender differences in the threshold for labeling ambiguous cues as sexual in nature, little research has been conducted to determine etiology. Using a model that differentiates perceptual sensitivity from decisional bias, we found no evidence that men have lenient thresholds for perceiving women's nonverbal behavior as indicating sexual interest. Rather, gender differences were captured by a relative perceptual insensitivity among men. Just as in previous studies, men were more likely than women to misperceive friendliness as sexual interest, but they also were quite likely to misperceive sexual interest as friendliness. The results point to the promise of computational models of perception in increasing the understanding of clinically relevant social processes.

Decoding sexual intent is an arguably difficult task, particularly if the perceiver hopes to decode intent early in an interaction. Women may smile, sustain eye contact, increase physical proximity, or touch their partner to convey romantic or sexual interest. However, all of these cues also could be used to convey simple warmth, friendliness, or platonic interest. Given ambiguity in separating sexual interest from platonic interest and the overlapping nonverbal cues used to signal these two kinds of interest, it should come as no surprise that individuals often disagree about the meaning of nonverbal sexual signals. In particular, men often disagree with women about the presence or degree of women's sexual intent (see Farris, Treat, Viken, & McFall, 2008, for a review). Men consistently rate female targets as intending to convey a greater degree of sexual interest than do women who rate the same targets—a finding that has been remarkably consistent across studies ranging from those using still photographs and video vignettes to those using live, unscripted interactions (e.g., Abbey, 1982; Abbey & Melby, 1986; Shotland & Craig, 1988). This gender difference in ratings of sexual intent is stable, is readily replicable, and has a medium effect size (Farris et al., 2008).

The effect is not confined to the lab. In a large survey of university women, 67% reported that they had experienced an incident in which a male acquaintance misperceived their friendliness to be an indication of sexual interest, and 26% reported that such an event had occurred within the past month (Abbey, 1987; see also Haselton, 2003). In most cases, the negative consequences of sexual misperception will not extend beyond minor social discomfort. However, among a subgroup of individuals, sexual misperception may play an etiological role in the process that ultimately leads to sexual coercion. Sexually coercive men are more likely than noncoercive men to report incidents of sexual misperception (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004; Abbey, McAuslan, & Ross, 1998). Thus, understanding the etiology of gender differences in perception of sexual intent may provide insight into the origins of this normative effect and also inform efforts aimed at preventing sexual coercion.

Two main theories have been offered to explain the source of these observed gender differences. The first is a decisional-threshold (or bias) theory, according to which men require fewer impelling cues than women before labeling a woman's behavior as sexual (Haselton & Nettle, 2006; Koukounas & Letch, 2001; Shotland & Craig, 1988). In this interpretation, men and women perceive the same positive behavioral cues, but men are more likely to label those cues as indicative of sexual interest because they have a more lenient decisional threshold than women do. Women are assumed to wait for more compelling sexual-interest cues before being willing to apply the label of sexual interest. It has been suggested that men may develop lenient thresholds for sexual interest through socialization processes that encourage men to be sexually avid and dominant (Abbey, 1982). Evolutionary psychologists have also been strong proponents of a bias interpretation of gender differences in perception of sexual interest, suggesting that it would have been sexually adaptive for men to have a low threshold for detecting probable or even possible mating partners (Haselton & Buss, 2000).

The second theory regarding the source of the gender difference posits that men misperceive sexual interest not because they have a low threshold for labeling sexual interest, but rather because they are less sensitive to women's nonverbal cues than women are and find it perceptually difficult to differentiate the subtle cues that discriminate women's sexual interest from their platonic interest (Abbey & Harnish, 1995, p. 298; Farris et al., 2008). This theory places men's performance in perception of sexual interest within the broader context of studies demonstrating that compared with women, men are less sensitive to emotional signaling across a broad range of affect categories (Hall, 1978; McClure, 2000). Such insensitivity may be particularly relevant among young men who are just entering the dating system, and therefore may not have acquired the experience necessary to reliably and accurately discriminate between women's platonic- and sexual-interest cues. If differences in sensitivity to intent describe the perceptual process by which men's and women's judgments come to differ, then one would expect that compared with women, men would make more decisional errors in both directions; that is, they not only would be more likely to mistake women's friendliness for sexual interest, but also would be more likely to mistake women's sexual interest for friendliness.

Despite strong theory and empirical interest in this area, the underlying source of observed gender differences in sexual perception has never been empirically measured and tested. Fortunately, measurement models capable of determining if gender differences in classification patterns reflect bias differences in decisional thresholds or relative insensitivity to different affective categories can be readily translated from simple perception applications in cognitive science. In fact, the implementation of these models in clinical cognitive science is part of a general movement to translate cognitive models in order to be more quantitatively and theoretically explicit about socially and clinically relevant processes (e.g., McFall & Treat, 1999; Neufeld, 2007). Luce's choice model (Luce, 1959, 1963; Macmillan & Creelman, 2004), closely aligned with the more commonly utilized signal detection theory (SDT; Green & Swets, 1966), provides a simple, computational model that matches the current needs of the field. It provides two parameter estimates that model the perceptual and decisional mechanisms that underlie previously documented gender differences in judgments about women's interest. Fitting the model to participants' identification data provides separate estimates of decisional bias and perceptual sensitivity for each individual. By collapsing individual estimates across gender, one can assess the separate contributions of bias and sensitivity to the observed gender differences in identification.

In the current study, we sought first to replicate the finding that men are more likely than women to misperceive women's friendliness as sexual interest. Provided this historically stable empirical result was replicated in our data, we sought to extend the analysis by modeling the underlying source of the gender difference using Luce's (1959) choice model. Given that formal computational models have never been employed to parse the source of the gender difference, and given that strong theoretical context supports both bias and sensitivity explanations, we approached the research from an exploratory perspective, with an emphasis on methodology capable of uncovering support for one or both theories. In addition, we examined men's and women's response to women's negative nonverbal cues in order to provide a dating-relevant counterpoint that would help clarify the specificity versus generalizability of any gender differences in the perception of women's nonverbal cues.

Method

Participants

Two hundred eighty heterosexual undergraduate men (63.6%) and women (36.4%) participated in exchange for course credit. The sample was predominantly White-Caucasian (85.4%; 3.6% African American, 5.0% Asian or Asian American, 2.5% Hispanic, 3.6% other), and the average age was 19.6 years (SD = 1.72).

Identification Task

Seated in a private computer room, participants categorized each of a series of photo images of women into one of four categories: friendly, sexually interested, sad, or rejecting. Each participant was randomly assigned to view the images for 500 ms or 3,000 ms. The 500-ms presentation time was sufficiently short to make it challenging to decode all relevant information thoroughly; the 3,000-ms presentation time provided ample opportunity for thorough processing. Participants viewed the images in four blocks of 70 randomly ordered images, with a 30-s pause separating successive blocks.

Stimulus Set

Extensive pilot testing produced a set of 280 full-body images of clothed women displaying one of the four dating-relevant emotions. Initially, a sample of 497 undergraduate men provided normative ratings of 1,127 images of undergraduate women who displayed a variety of emotions and wore different clothing styles. The men used 7-point scales to rate how friendly, sexually interested, sad, rejecting, attractive, and provocatively dressed each woman was. Those images rated above the median on the scales of interest were retained for consideration. From this group, we selected images such that approximately half of the retained images were rated above the midpoint for provocative dress. Note that the women in the photos were instructed to select clothing from their own wardrobes; therefore, the variance along the clothing-style continuum is representative of the range of clothing styles that a college student would observe among his or her peers.

As the final step in generating the photo set, we asked a new sample of undergraduates (80 men and 80 women) to categorize the women in the photographs as friendly, sexually interested, sad, or rejecting. A photograph was retained if the majority of men and the majority of women categorized the picture into the same affect group. We used a majority criterion, rather than a strong-consensus criterion, to ensure some variability within each category, as variability is required to model the theoretically relevant perception parameters. Finally, in selecting the photographs to be used in the experiment, we examined attractiveness ratings from the original normative sample and ensured that attractiveness was held constant across the four target types. The final set of 280 photographs consisted of 70 images in each of the four affect categories.

Analysis

Choice-model parameters, sensitivity and bias, were estimated for each participant individually (see Luce, 1959, 1963; Macmillan & Creelman, 2004, pp. 95–97, 247–250). The sensitivity parameter α provides a quantitative estimate of an observer's ability to perceptually distinguish between categories. It is computed as follows:

where H is the proportion of hits (i.e., the probability of correctly identifying the target) and FA is the proportion of false alarms (i.e., the probability of incorrectly identifying a nontarget as the target). The formula essentially computes a ratio of correct responses to incorrect responses, and thus the value of alpha increases positively as discrimination improves. This general formula is modified for forced-choice tasks with two or more alternatives, such as the identification task we used. For the current study, ln(α) was used to estimate sensitivity:

where m is the number of response categories, P(Ri|Si) is the probability of a correct response to stimulus i, and P(Rj|Si) is the probability of an incorrect response to stimulus i. Ln(α) is zero when the participant is wholly unable to perceive the category structure and increases positively as sensitivity improves. In our stimulus set, near-perfect sensitivity would correspond to an estimate of 4.63. We calculated four sensitivity estimates, one corresponding to each of the four affect categories (the participant's ability to discriminate friendliness from all other categories, sexual interest from all other categories, etc.). Readers more comfortable interpreting sensitivity within a signal detection framework may find it helpful to approximate the SDT sensitivity parameter (d′) by dividing ln(α) by 0.81 (Macmillan & Creelman, 2004).

The bias parameter quantifies an observer's response preference. The general formula is as follows:

Thus, b is the ratio of the observer's tendency to use one response over another. For identification tasks with more than two response categories, bias can be computed as a ratio between two response tendencies (Macmillan & Creelman, 2004). We chose to examine the theoretically relevant pairs friendly versus sexually interested (positive affect) and sad versus rejecting (negative affect). The bias parameter can be thought of as an estimate of the threshold at which the participant's categorization of women's behavior switches from one category to another. It was computed as follows:

where bi/bj is the ratio of a subject's bias to provide response i over his or her bias to provide response j, P(Ri|Sk) is the probability of providing response i to stimulus k, and P(Rj|Sk) is the probability of providing response j to stimulus k.

For the current study, two decisional-bias estimates were computed for each participant. Positive-affect bias, ln(bfr|bsi), refers to the category boundary between friendliness (“fr”) and sexual interest (“si”). A value near zero indicates balanced category responses (i.e., the participant was no more likely to respond that positive affect reflected friendliness than to respond that it reflected sexual interest). This estimate becomes increasingly positive the more likely participants are to indicate that positive affect reflects friendliness and becomes increasingly negative the more likely participants are to indicate that positive affect reflects sexual interest. Computing this estimate allowed us to evaluate the prediction that men would be biased to perceive sexuality in women's ambiguous nonverbal behavior. A significantly lower bias estimate for men than for women would indicate that men have a lower threshold for perceiving sexual intent in women's nonverbal displays.

The second bias estimate captures negative-affect bias, ln(bsd|brj), or the category boundary between sadness (“sd”) and rejection (“rj”). Negative-affect bias increases positively as participants become more likely to respond that negative affect is sadness and declines negatively as participants become more likely to respond that negative affect is rejection.

In our stimulus set, almost exclusive reliance on one category response would produce a bias estimate of ±6.55 for either positive-affect bias or negative-affect bias. Relying on one category for 70% of all judgments, with equally distributed errors, would produce a bias estimate of ±1.95.

Statistical Analysis

A general linear model (GLM) approach was used to explore gender differences in heterosocial perception as quantified by the choice-model parameters of sensitivity and bias. We report models predicting the following dependent variables: (a) positive-affect sensitivity, (b) negative-affect sensitivity, (c) positive-affect bias, and (d) negative-affect bias. All models included gender, clothing style (conservative vs. provocative), and presentation time (500 ms vs. 3,000 ms) as predictors. However, presentation time did not interact significantly with gender in any of the analyses reported. The sensitivity models also included an affect factor to discriminate the two types of positive affect (friendliness vs. sexual interest) or negative affect (sadness vs. rejection).

Results

The confusion matrix in Table 1 provides a descriptive overview of men's and women's categorization of the image set. Note that for all affect categories, women categorized more images correctly than men did. Of course, inaccuracy is the effect of specific interest, particularly in the set of images normatively judged to portray friendliness, as misclassification of friendly women as sexually interested has been the primary area of interest in previous research. As in prior studies, men were more likely than women to misidentify friendly targets as indicating sexual interest (12.1% vs. 8.7%), t(271.4) = 3.39, p < .01, d = 0.38.1 If this error were due to a tendency to oversexualize the image set, men should also have been more accurate than women at decoding the cues of sexually interested targets. However, Table 1 reveals the opposite; men were more likely than women to misidentify sexually interested targets as indicating friendliness (37.8% vs. 31.9%), t(287) = 3.03, p < .01, d = 0.40.

TABLE 1. Confusion Matrix Summarizing Male and Female Participants' Categorization Accuracy.

| Participants' responses (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friendly | Sexually interested | Sad | Rejecting | |||||

| Target category | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| Friendly | 79.9 | 87.0 | 12.1 | 8.7 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 2.7 |

| Sexually interested | 37.8 | 31.9 | 48.9 | 59.2 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 8.7 | 6.3 |

| Sad | 10.3 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 62.3 | 68.3 | 22.0 | 20.8 |

| Rejecting | 13.7 | 10.7 | 5.3 | 6.6 | 23.1 | 21.1 | 57.9 | 61.7 |

Note. Percentages for correct responses are in boldface.

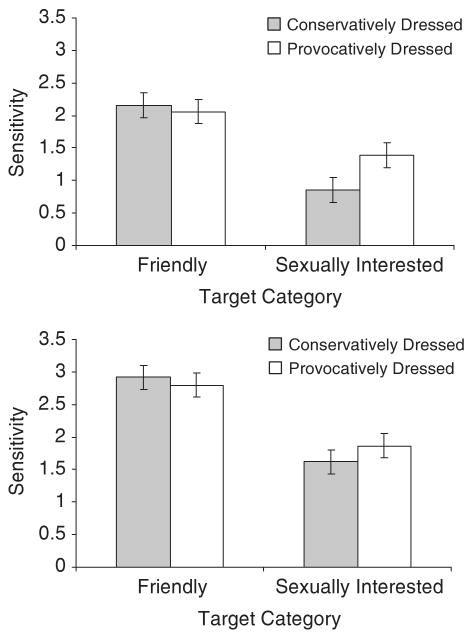

The statistical model predicting choice-model parameter estimates of sensitivity to positive affect parsed the source of this descriptive evidence. Compared with women (ln(α) = 2.30), men (ln(α) = 1.61) were significantly less sensitive to the distinction between friendliness and sexual interest, F(1, 278) = 123.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .326. The main effect for gender was modified by a three-way interaction among gender, clothing style, and affect, F(1, 278) = 7.46, p < .01, ηp2 = .026, depicted in Figure 1. Post hoc analyses revealed that both men and women were more sensitive to cues signaling friendliness than to cues signaling sexual interest (Tukey's HSD, p < .01). However, perceptual sensitivity varied as a function of clothing style among men only. The provocativeness of target women's clothing was not associated with men's sensitivity to friendliness; however, when a target woman was signaling sexual interest, men were more sensitive to her nonverbal cues when she was dressed provocatively (ln(α) = 1.39), rather than conservatively (ln(α) = 0.86, p < .01).

Fig. 1.

Mean sensitivity to friendliness and sexual interest as a function of the target's clothing style, for men (top panel) and women (bottom panel). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals, computed according to Masson and Loftus's (2003) recommendations for between- and within-subjects designs.

Gender differences in sensitivity also characterized decoding of women's negative-affect cues. Compared with women (ln(α) = 1.68), men (ln(α) = 1.36) were less sensitive to target women's sad and rejecting nonverbal cues, F(1, 278) = 33.28, p < .001, ηp2 = .107. The two-way interaction between gender and affect (sad vs. rejecting), F(1, 278) = 9.62, p < .01, ηp2 = .033, was significant. However, post hoc tests did not reveal significant differences between men's differential sensitivity to sad (ln(α) = 1.43) versus rejecting (ln(α) = 1.28) affect and women's differential sensitivity to sad (ln(α) = 1.89) versus rejecting (ln(α) = 1.47) affect.

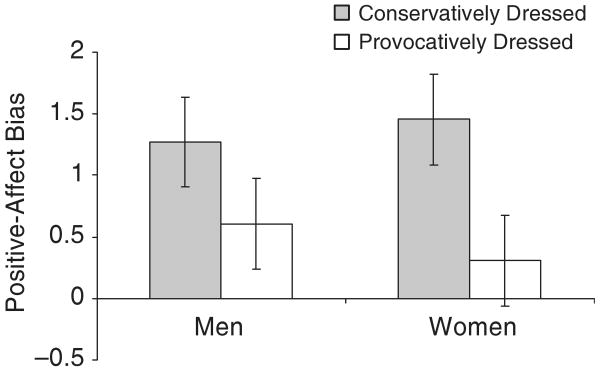

A separate GLM predicting choice-model positive-affect bias estimates was estimated. The analyses revealed that men and women had nearly identical thresholds for labeling positive affect sexual interest, ln(bfr|bsi) = 0.94 vs. 0.88, respectively, F(1, 278) = 0.323, p = .57. The positive values of the parameter estimates indicate that both men and women were biased to assume that positive affect was friendliness, rather than sexual interest (within this image set). A significant interaction between gender and clothing style, F(1, 278) = 22.49, p < .001, ηp2 = .075, depicted in Figure 2, revealed that women modified their decisional criterion for detecting sexual interest on the basis of clothing style (Tukey's HSD, p < .01). They adopted a more lenient criterion for labeling positive affect sexual interest when target women were dressed provocatively and a more stringent criterion when target women were dressed conservatively. The same pattern was reflected in men's decisional processes, but was not significant in post hoc analyses.

Fig. 2.

Mean estimates of positive-affect bias as a function of the participant's gender and the target's clothing style. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals, computed according to Masson and Loftus's (2003) recommendations for between- and within-subjects designs.

Finally, the statistical model predicting choice-model negative-affect bias estimates revealed a main effect for gender only, F(1, 278) = 6.45, p < .05, ηp2 = .023. Women had a lower decisional threshold for labeling negative affect rejection than did men, ln(bsd|brj) = −0.365 versus −0.125, respectively. Women were more likely than men to respond that target women's negative affect indicated rejection, rather than sadness.

Discussion

The present evaluation of gender differences in perception of sexual intent replicated the long-standing finding that men are more likely than women to misperceive sexual intent in women's displays of friendliness and showed that gender differences in perceptual sensitivity accounted for this result. Men found platonic-interest cues to be less discriminable from sexual-interest cues than women did. Just as in previous research, they made some mistakes in perceiving sexual intent in friendly displays, but they also misperceived friendliness in sexual-interest displays. That is, they oversexualized some women, but were quite likely to undersexualize other women. Although the methodology varied from that used in early research (we employed an identification paradigm and a series of photographs), the effect sizes (d = 0.38–0.40) were consistent in magnitude with the average effect sizes reported in previous investigations (Farris et al., 2008). Employing a model-based approach capable of parsing decisional bias from perceptual insensitivity, we found no evidence that men's performance differed from women's because of a gender difference in decisional thresholds for positive-affect targets. Relative to women, men did not oversexualize the image set, and their decisional criteria for detecting sexual intent were no more or less lenient than women's. For this image set, the underlying etiology differentiating men's performance from women's performance was perceptual sensitivity.

In the case of negative affect, men also showed a relative insensitivity to nonverbal cues. Women were more sensitive than men to the distinction between sadness and rejection; however, the effect size for the gender difference in sensitivity was larger within positive-affect categories than within negative-affect categories (.326 vs. .107, respectively). This might suggest that although there is a general tendency for women to be more successful than men at decoding nonverbal cues (Hall, 1978; McClure, 2000), there is a particularly pronounced gender difference when nonverbal cues are sexual in nature. Future research that will continue to explore the magnitude and the boundaries of gender differences in social perception is warranted. In any case, within the realm of sexual bargaining, and sexual coercion in particular, skill in decoding sexual intent may be principally crucial in successfully negotiating sexual relationships, and warrants continued attention.

It is important to note that participants in this study were asked to judge affect from relatively impoverished stimuli. Social and sexual communication often occurs in a dynamic and reciprocal interchange between actors. Over time, perceivers may accumulate information about a potential partner's interest in order to change or refine interpretation of that person's behavior. It will be important for future research to explore gender differences in bias and sensitivity in response to richer stimuli, such as videotaped vignettes or scripted, live interactions, in order to establish whether gender differences in sensitivity generalize to such stimuli (and whether gender differences in bias come into play). At the same time, first-impression judgments, such as those captured in responses to briefly displayed still photographs, may also influence social perception across longer time scales, and thus merit continued consideration.

Finally, the question remains as to how to resolve the lack of gender differences in the bias parameter with women's observations of their own social interactions. Women self-report many incidents in which their attempts to be friendly are misperceived as displays of sexual interest (Abbey, 1987), but do not seem to have the opposite problem of displaying sexual interest only to have it ignored as mere friendliness (Haselton, 2003). If men misperceive positive-affect cues more often than women because of greater insensitivity, should they not take sexual interest to be friendliness as often as they take friendliness to be sexual interest? Are the unequal frequencies of reports of the two types of misperception an indicator that men have a relative bias in the natural environment, even if they fail to display that bias in the laboratory?

We believe that women's self-reports do not challenge the laboratory findings for several reasons. First, women's observations about misperception of their intent would be reliable only if women had access to the internal perceptual and decisional processes of their social partners, but this is an unlikely assumption. Instead, women probably rely on men's behavioral cues to infer men's perception of interest. The behavioral cues that suggest a man has misperceived friendliness as sexual interest are more likely to be inappropriate and memorable than the cues that suggest a man has misperceived sexual interest as friendliness. Indeed, a man who has misperceived sexual intent as friendliness may not provide any diagnostic behavior cues (failure to pursue could be an indicator of misperception, but could just as easily be explained by noninterest). Thus, women may note misperceived friendliness more readily than misperceived sexual interest.

Second, the behavioral cues often attributed to misperceived friendliness (e.g., continued advances) may not be produced solely by misperception, but may also be produced after a man accurately perceives noninterest but continues to approach in order to convince, cajole, or persuade. Finally, and most important, base rates must be considered before concluding that observed frequencies of misperceived friendliness versus misperceived sexual interest reflect bias (Dawes, 1986). Base rates of friendliness and sexual interest in the natural environment are likely to be widely discrepant. A woman may have dozens if not hundreds of friendly interactions with men for every one interaction in which she signals sexual interest. Thus, there are many more opportunities for insensitivity to be exposed (and noted by women) within friendly interactions than within interactions characterized by sexual interest. Women's reports of experiencing misperception of friendliness more frequently than misperception of sexual interest are not inconsistent with gender differences in sensitivity, and may be explained by the unequal base rates of women's use of friendliness and sexual-interest cues.

In summary, parameter estimates provide preliminary support for the argument that disagreements between men and women about the meaning of women's positive-affect displays are the result of a perceptual difference such that men have more difficulty discriminating sexual interest from friendliness, rather than the result of a tendency among men to oversexualize women's nonverbal displays. By relying on rigorous, computational modeling techniques, the measurement strategy for the present study was well matched to the theoretical question of interest and made it possible to parse the perceptual and decisional processes hypothesized to underlie the observed disagreement between men and women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32-MH17146) and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31-AA016055).

Footnotes

Given that the primary aim of this study was to explore the source of observed gender differences in heterosocial perception, only those effects that involve gender are reported here. In a previous publication (Farris, Viken, Treat, & McFall, 2006), we reported significant experimental effects independent of gender in the men's sample.

References

- Abbey A. Sex differences in attributions for friendly behavior: Do males misperceive females' friendliness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;42:830–838. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A. Misperceptions of friendly behavior as sexual interest: A survey of naturally occurring incidents. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1987;11:173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Harnish RJ. Perception of sexual intent: The role of gender, alcohol consumption, and rape supportive attitudes. Sex Roles. 1995;32:297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P. A longitudinal examination of male college students' perception of sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:747–756. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Ross LT. Sexual assault perpetration by college men: The role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1998;17:167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Melby C. The effects of nonverbal cues on gender differences in perceptions of sexual intent. Sex Roles. 1986;15:283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes RM. Representative thinking in clinical judgment. Clinical Psychology Review. 1986;6:425–441. [Google Scholar]

- Farris C, Treat TA, Viken RJ, McFall RM. Sexual coercion and the misperception of sexual intent. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:48–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris C, Viken R, Treat T, McFall R. Heterosocial perceptual organization: Application of the choice model to sexual coercion. Psychological Science. 2006;17:869–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal detection theory and psychophysics. New York: Wiley; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA. Gender effects in decoding nonverbal cues. Psychological Bulletin. 1978;85:845–857. [Google Scholar]

- Haselton MG. The sexual overperception bias: Evidence of a systematic bias in men from survey of naturally occurring events. Journal of Research in Personality. 2003;37:34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Haselton MG, Buss DM. Error management theory: A new perspective on cross-sex mind reading. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:81–91. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselton MG, Nettle D. The paranoid optimist: An integrative evolutionary model of cognitive biases. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:47–66. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukounas E, Letch NM. Psychological correlates of perception of sexual intent in women. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;141:443–456. doi: 10.1080/00224540109600564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce RD. Individual choice behavior. New York: Wiley; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Luce RD. Detection and recognition. In: Luce RD, Bush RR, Galanter E, editors. Handbook of mathematical psychology. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 1963. pp. 103–189. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection theory: A user's guide. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Masson MEJ, Loftus GR. Using confidence intervals for graphically based data interpretation. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2003;57:203–220. doi: 10.1037/h0087426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB. A meta-analytic review of sex differences in facial expression processing and their development in infants, children, and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:424–453. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall RM, Treat TA. Quantifying the information value of clinical assessments with Signal Detection Theory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:215–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld RWJ, editor. Advances in clinical cognitive science: Formal modeling of processes and symptoms. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shotland RL, Craig JM. Can men and women differentiate between friendly and sexually interested behavior? Social Psychology Quarterly. 1988;51:66–73. [Google Scholar]