Abstract

Background: Systemic agents in cancer treatment were often associated with possible infusion reactions (IRs). This study estimated the incidence of IRs requiring medical intervention and assessed the clinical and economic impacts of IRs in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) treated with cetuximab.

Patients and methods: Details on patients with CRC receiving cetuximab in 2004–2006 were extracted from a large USA administrative claims database. IRs were identified based on the occurrence of outpatient treatment, emergency room (ER) visit, and/or hospitalization for hypersensitivity and allergic reactions. Multivariate regressions were used to examine potential risk factors and quantify the economic impact of IRs.

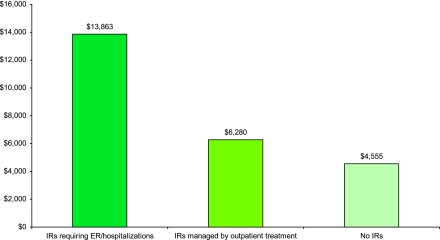

Results: A total of 1122 CRC patients receiving cetuximab were identified. The incidence of IRs requiring medical intervention was 8.4%. Sixty-eight percent of the patients had treatment disruptions and 34% discontinued cetuximab treatment. Mean adjusted costs were $13 863 for cetuximab administrations with an IR requiring ER visit or hospitalization and $6280 for those with an IR requiring outpatient treatment, compared with $4555 for those without an IR.

Conclusions: The incidence rate of cetuximab-related IRs requiring medical intervention in clinical practice was found to be higher than rates reported in the product label and clinical trials. The clinical and economic impacts of these IRs are substantial.

Keywords: cetuximab, claims data, colorectal cancer, infusion reaction

introduction

Infusion reactions (IRs) have been documented with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) as well as with other cancer therapies that are administered i.v. [1, 2]. The severity of IRs varies from mild itching, flushing, and fever to life-threatening cardiopulmonary events. In a few extreme cases, deaths have resulted from severe IRs [2–4].

Severe IRs occurred in 2.3%–5% of patients treated with cetuximab in clinical trials [2]. Nevertheless, recent studies have reported higher incidence rates of severe IRs among patients receiving cetuximab. In a prospective, multicenter time-and-motion study of patients with cancer using cetuximab, Schwartzberg et al. [4] found that 7% of patients experienced severe IRs. O'Neil et al. [5] examined IR rates in patients treated with cetuximab in medical centers from Tennessee and North Carolina and found that 22% of patients experienced severe IRs.

Limited data exist to identify risk factors that might predispose patients to severe IRs. Atopic history and residence in the middle southern region of the United States have been found associated with high incidence of severe IRs [5, 6]. Although the prescribing information for cetuximab indicates that 90% of severe IRs occurred during the initial cetuximab administration [7], Needle [8] reported that 33% of patients with severe IRs experienced events after their second dose of cetuximab. Lenz [2] also noted that 10%–30% of IRs to MAbs are delayed and occur in later infusions.

The published literature on the clinical and economic burden of severe IRs in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) is currently limited. In a time-and-motion study of patients with cancer, those patients who had an IR required between 31% and 80% additional staff time [4]. A retrospective study of patients who suffered severe IRs found that 22% were hospitalized and had an average length of stay of 4 days [3]. In addition to increased resource utilization, 87% of oncology nurses participating in an oncology practice survey reported that both patients and clinicians feel ‘fear’ and ‘stress’ even with the occurrence of mild IRs [9]. O'Neil et al. [5] also noted that the experience of an IR can be traumatic for patients, family members, and the clinical staff managing these events. Although some studies begin to provide assessments of the clinical and economic burden of IRs, only one study estimated the cost impact of IRs on staff time [4].

Given lack of data on incidence, risk factors, and clinical and economic impacts of IRs in real-world clinical practice, the objectives of this study were to (i) estimate the incidence rate of IRs requiring medical intervention among patients with CRC treated with cetuximab using a large USA health insurance claims database, (ii) evaluate potential risk factors for developing IRs, and (iii) quantify the clinical and economic impacts of IRs during the course of treatment in patients with CRC.

patients and methods

overview

A retrospective observational study was conducted using a large USA claims database. Study participants were patients with CRC receiving cetuximab treatment from 2004 to 2006. Cetuximab administrations were examined for incidence of IRs requiring medical intervention. IRs were identified based on multiple indicators including outpatient treatments, emergency room (ER) visits, and/or hospitalizations for hypersensitivity and allergic reactions. The clinical impact of IRs was assessed through the identification of treatment disruptions (cetuximab dose delay, reduction, rechallenge, and permanent discontinuation), and the economic impact was calculated as the incremental direct costs associated with the IRs. Additionally, risk factors for developing IRs were explored.

data sources

Data were extracted from MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounter Database and the Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Database from Thomson Reuters. Combined, these two Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant databases include patient-level medical and pharmacy claim histories for about 30 million commercially insured lives in the United States annually. Enrollees in the MarketScan databases are covered under a variety of plan types, including both capitated [e.g. health maintenance organization (HMO)] and non-capitated (e.g. fee-for-service) product lines. The databases capture the full continuum of insurance-reimbursable services delivered across all care settings including physician office visits, ER visits, hospital stays, and outpatient pharmacy claims. A comparison of the population demographic characteristics in the MarketScan database with the overall USA population with employer-sponsored health insurance as reported in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) found minimal differences in the overall age and gender distributions. Compared with MEPS, patients living in the western region of the United States are underrepresented in the database and those in the southern region overrepresented.

eligible patients

Study patients were identified based on the occurrence of at least one claim containing a code for cetuximab administration (HCPCS J9055, C9215) from July 2004 to December 2006. The service date of the first cetuximab claim was defined as the index date. Patients were required to have a CRC diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes 153.0–153.4, 153.6–153.9, 154.0, 154.1, and 154.8) and be ≥18 years on the index date. Patients needed to have continuous medical and pharmacy benefits coverage for the 180 days before the index date. Patients should have no other cetuximab claims in the 180-day pre-period. Because bevacizumab, another MAb indicated for CRC, is also associated with IRs, patients with claims of bevacizumab administration within 14 days of cetuximab administration were excluded. A 14-day time window was used because bevacizumab is typically administered biweekly.

IR identification

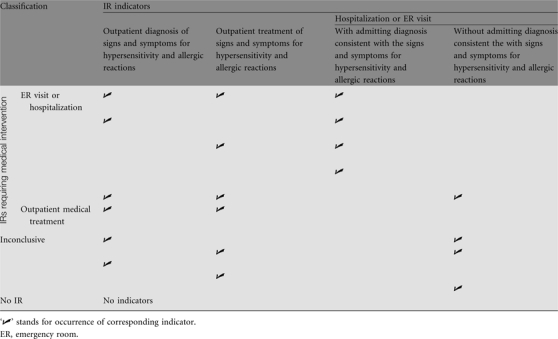

IRs can be identified and graded by evaluating changes in health status and symptoms, or by assessing medical interventions taken to manage IRs. Given that this study used medical claims data, IRs were identified according to IR-related diagnoses and claims indicative of medical interventions that would be associated with the treatment of an IR. An algorithm using a combination of three indicators, described in the following, was applied to each cetuximab administration to identify and classify IRs. Because close monitoring for up to 72 h is recommended for patients who experience an IR [10], the time interval for identifying an IR included the day of cetuximab administration and the subsequent 2 days.

The first indicator of an IR was based on outpatient claims with ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes consistent with the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity and allergic reactions, such as anaphylactic shock, angioneurotic edema, bronchospasm, cardiac arrest, dyspnea, and hypotension. These signs and symptoms were extracted from the cetuximab product label [7]. The second indicator was outpatient treatment based and included medication and procedure codes for treatments consistent with the management of signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity and allergic reactions in the outpatient setting [2, 10, 11]. Treatment included epinephrine, inhaled bronchodilators (i.e. short-acting beta-agonists in aerosolized form), two or more doses of antihistamines, two or more doses of corticosteroids, two or more administrations of i.v. fluids, glucagons (in combination with beta-blockers), oxygen, and vasopressors. The third indicator was based on the occurrence of an ER visit or inpatient admission.

The algorithm was developed to identify IRs by the intensity of medical interventions based on the combinations of the three indicators. These three indicators were examined simultaneously for each cetuximab administration, resulting in 12 distinct combinations. These 12 groups were further aggregated into four IR categories: IRs requiring an ER visit or hospitalization, IRs requiring outpatient medical treatment, inconclusive IRs, and no IR (Table A1). An IR requiring medical interventions occurred if (i) there was an ER visit or hospitalization with an admitting diagnosis consistent with the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity and allergic reactions or (ii) there were both outpatient diagnosis and outpatient treatment consistent with the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity and allergic reactions. Because this study focused only on IRs that required intensive resource use, all other combinations of indicators were deemed as inconclusive evidence of an IR.

Several variables were constructed to quantify the clinical impact of IRs requiring medical intervention on the course of CRC treatment, including dose reduction, dose delay, dose rechallenge, and dose discontinuation. Dose delay was coded when the number of days between the current infusion and the following infusion was ≥14 days. As the actual dose of cetuximab was not consistently available in the database, dose reduction was determined through analysis of cetuximab payments and defined as a decrease in payment of at least 10% between successive cetuximab claims. Dose reductions between the first and second cetuximab administrations, however, were not included due to a loading dose of cetuximab on the initial infusion. Dose rechallenge was defined as subsequent cetuximab administration within 2 days of the cetuximab administration being evaluated. Dose discontinuation was defined as no further cetuximab claims after the administration being evaluated.

costs of IRs

In the MarketScan databases, costs are defined as the total reimbursed amount delivered to facilities (e.g. hospitals, laboratories, pharmacies) or medical professionals (e.g. physicians, nurse practitioners) for the services delivered. Costs are documented for each individual visit or encounter with health professionals, each hospitalization, or each prescription fill. The reimbursed amounts include the health plan-paid amounts and any applicable patient-paid co-pays, coinsurance, and deductibles. This amount is sometimes referred to as the ‘allowed amount’. Allowed amounts are based on negotiated rates by the individual health plans with individual facilities and providers. Hospitalization payments are often based on negotiated diagnosis-related group-level fee amounts.

The cost of an IR was defined as the difference between the mean cost per cetuximab administration with IR requiring medical intervention and that for those administrations without any IRs. Costs for cetuximab administrations were calculated for claims of health care resource use within the 3-day window of the cetuximab administrations being evaluated. For hospitalizations with an admitting diagnosis consistent with the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity and allergic reactions and an admission date in the 3-day window, the cost of this hospitalization was included. All costs were converted to constant 2006 USA dollars using the consumer price index for medical care.

statistical analyses

Baseline patient demographic and clinical variables, including age, gender, geographic region, insurance type, residence in a pollen state, atopic history, site of primary tumor, and use of platinum chemotherapies, were described and compared between patients experiencing IRs requiring medical intervention and those having no IRs. A logistic regression was used to examine potential risk factors associated with IRs. Variables in the model included patient demographic and clinical characteristics, Deyo–Charlson comorbidity index, and whether the infusion was an initial administration of cetuximab.

Adjusted costs for cetuximab administrations were estimated using a generalized linear model (GLM) with a gamma distribution and log link function while controlling for patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Robust standard error estimates were obtained to account for the occurrence of multiple infusions per patients.

results

patient characteristics

A total of 1122 patients with CRC received cetuximab during the study period. Overall, the mean age (standard deviation) of the patients was 61.2 years (11.8), 55% were male, and nearly 85% lived in an urban setting. Patients had various types of insurance coverage: 41.9% were enrolled in preferred provider organization, 31.6% had comprehensive fee-for-services, and 15.5% in an HMO. Approximately 20% of the patients resided in a pollen state and 13.3% had an atopic history. Seventy percent of the population had primary tumor at the colon. Almost half (46%) of the patients had at least one concomitant platinum chemotherapy administration during their use of cetuximab.

Patients with IRs requiring medical intervention were compared with those without any IRs on patient characteristics (Table 1). Overall, these two groups of patients were similar, with the exception of age, such that patients with IRs were slightly younger (57 versus 62 years, P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | CRC patients with IRs (n = 94) |

CRC patients without IRs (n = 1028) |

P value | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age, years | 57.5 | 11.1 | 61.6 | 11.8 | 0.001 |

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Male | 55 | 58.5 | 563 | 54.8 | 0.490 |

| Colon (versus rectum) | 63 | 67.0 | 718 | 69.8 | 0.572 |

| Urban (versus rural residence) | 77 | 81.9 | 875 | 85.1 | 0.408 |

| Geographic region | 0.257 | ||||

| Northeast | 3 | 3.2 | 98 | 9.5 | |

| North central | 31 | 33.0 | 324 | 31.5 | |

| South | 43 | 45.7 | 397 | 38.6 | |

| West | 17 | 18.1 | 208 | 20.2 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Living in pollen-sensitive state | 26 | 27.7 | 202 | 19.6 | 0.062 |

| Allergy history | 15 | 16.0 | 134 | 13.0 | 0.412 |

| Insurance plan type | 0.059 | ||||

| Comprehensive FFS | 20 | 21.3 | 334 | 32.5 | |

| HMO | 17 | 18.1 | 157 | 15.3 | |

| PPO | 49 | 52.1 | 421 | 41.0 | |

| POS—capitated | 2 | 2.1 | 8 | 0.8 | |

| POS—non-capitated | 6 | 6.4 | 86 | 8.4 | |

| Other/unknown | 0 | 0 | 22 | 2.1 | |

| Concomitant platinum chemotherapies use | 41 | 43.6 | 470 | 45.7 | 0.696 |

CRC, colorectal cancer; FFS, fee-for-service; HMO, health maintenance organization; IR, infusion reaction; PPO, preferred provider organization; POS, point of service; SD, standard deviation.

incidence of IRs and clinical impact

A total of 8.4% (94 of 1122) of the patients treated with cetuximab experienced at least one IR requiring medical intervention. Of these 94 patients, 37 (39.4%) required an ER visit or hospitalization. Of the 37 patients, 35 had a single IR event and 2 a prior IR event that did not require an ER visit or hospitalization. The remaining 57 patients with an IR were managed in outpatient settings. Forty-one percent (39 of 94) of the patients experienced an IR event during their initial cetuximab administration. Sixty-eight percent of the patients experienced cetuximab treatment disruption, including dose reduction or delay (28.7%), permanent treatment discontinuation (34.0%), and dose rechallenge (5.3%). For patients who experienced IRs that required an ER visit or hospitalization, 52.8% discontinued cetuximab permanently.

risk factors for IRs

The logistic regression model indicated that after controlling for other patient characteristics, patients’ residence in a pollen state [odds ratio (OR): 2.67, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.27–5.62] and initial administrations (OR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.26–2.71) were associated with a statistically higher likelihood, and patient age (OR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.94–0.98) was associated with a statistically lower likelihood of having an IR requiring medical intervention (data not shown). Nevertheless, the effect of atopic history and concomitant use of platinum chemotherapy on experiencing an IR did not reach statistical significance.

costs of IRs

The costs for administrations with IRs requiring medical interventions and for those with no IRs were examined (Table 2). The unadjusted mean total cost for cetuximab administrations with IRs requiring hospitalization or ER visits was $15 729 and for those administrations with IRs managed at outpatient settings $7206, compared with the mean total cost of $4598 for administrations without any IR. Table 2 further shows that nearly $8000 was attributed to the hospital treatment of IRs requiring an ER visit or hospitalization. Over $2500 was due to outpatient care for post-IR management, such as corticosteroids, i.v. fluids, and utilization of the resuscitation cart (data not shown).

Table 2.

Costs associated with cetuximab administration by infusion reaction (IR) status

| IRs requiring ER visits or hospitalization (n = 37) |

IRs managed by outpatient treatment (n = 210) |

No IR (n = 7414) |

|||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | |

| Inpatient ($) | 7954 | 15 154 | 3206 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Inpatient LOS | 2.14 | 3.08 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ER ($) | 417 | 741 | 163 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Outpatient ($) | 7323 | 4329 | 6047 | 7099 | 5430 | 5986 | 4520 | 2976 | 3785 |

| Prescription ($) | 36 | 87 | 0 | 107 | 377 | 0 | 78 | 396 | 0 |

| Total ($) | 15 729 | 16 429 | 10 521 | 7206 | 5436 | 6019 | 4598 | 3017 | 3851 |

LOS, length of stay; ER, emergency room; SD, standard deviation.

The total costs were also examined through GLM multivariate regression analysis to adjust for patient characteristics. These results were similar to those before multivariate adjustment. The adjusted mean costs were $13 863 and $6280 for cetuximab administrations with IRs requiring an ER visit or hospitalization and outpatient treatment, respectively, compared with the mean cost of $4555 for those without any IRs (Figure 1). Thus, the adjusted incremental costs of IRs were $9308 when an ER visit or hospitalization was required and $1725 when only outpatient medical care was required to treat the IRs, as compared with those without IRs. Results from the model are presented in Table A2.

discussion

Using a large USA-based health insurance claims database, this study found that 1 in 12 patients using cetuximab therapy to treat their CRC experienced IRs that required medical intervention. This rate is significantly higher than the rate reported in the product label prescribing information. Treatment of IRs resulted in costs of $1725 per case if affected patients were treated on an outpatient basis and $9308 per case if the patient required treatment of the IR in the ER or was hospitalized. In addition to the incremental cost burden, more than two-thirds of the patients with IRs experienced disruptions in their treatment regimen.

Among CRC patients treated with cetuximab, 8.4% experienced IRs that required resource-intensive medical intervention, a rate that is two to three times higher than that of severe IRs reported in the cetuximab prescribing information (3%) [7] but lower than 22% reported by O'Neil et al. [5] for patients from North Carolina and Tennessee. Nevertheless, the incidence rate found in this study is consistent with the 7% reported by Schwartzberg et al. [4] in their prospective multicenter study.

With respect to potential risk factors for IRs, the results of this study were largely consistent with those reported in previously published literature. Although the initial cetuximab infusion was associated with higher risk for IRs, results from this study showed that nearly half of the IRs requiring medical intervention occurred beyond the first cetuximab infusion. This is consistent with a study by Needle [8] where 33% of patients who had severe IRs experienced events after their second dose. These findings indicate the importance of close monitoring following every cetuximab infusion.

Previous research found that the occurrence of IRs may result in the disruption of cetuximab administrations or discontinuation of the drug altogether [2, 3]. In our study, 68.1% of patients with severe IRs experienced cetuximab treatment interruption, of which 34% permanently discontinued cetuximab treatment. For patients who experienced severe IRs that required an ER visit or hospitalization, 52.8% discontinued cetuximab permanently. These findings are in line with those found in a retrospective chart review conducted in 19 USA oncology practice sites [3]. The significance of treatment discontinuation due to an IR is underscored by the fact that cetuximab is often administered to patients with disease progression following chemotherapy and thereby have limited treatment options.

Another key objective of this study was to quantify the economic burden associated with the management of IRs in cetuximab patients. Compared with cetuximab administrations without IRs, the mean costs for cetuximab administrations with IRs requiring an ER visit or hospitalization were more than two times higher ($13 863 versus $4555), resulting in an incremental cost of $9308. Even for IRs that were able to be managed in the outpatient setting, the incremental cost to payers was $1725, or ∼40% higher than a cetuximab administration without an IR.

This study leverages a claims-based data source to identify IRs that required medical intervention. Whereas previous studies on cetuximab-related IRs were limited to ∼100 cetuximab patients, the use of a large claims database allowed for this observational study of 1122 CRC patients receiving cetuximab from a geographically diverse sample of patients residing in different regions of the United States. Previous studies have shown the validity of using claims data to identify serious adverse events associated with biological agents, especially when multiple indicators based on diagnosis codes and inpatient and outpatient treatments were used [12, 13]. Because only IRs requiring an ER visit, hospitalization, or both outpatient diagnosis and treatment were analyzed in this study, we hypothesize that these IR cases may have been severe to life-threatening adverse events.

Similar to other observational studies, there are limitations to be considered when interpreting the findings from this study. First, there are no designated ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for IRs, and therefore, an algorithm was developed for identification of IRs based on medical interventions. To minimize misclassification, this study restricted the classification of IRs to those events with resource-intensive uses. Only an ER visit or hospitalization with admitting diagnoses of the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity and allergic reactions or both outpatient diagnoses and treatment of these signs and symptoms could qualify as a severe IR. Other cases were classified as inconclusive and excluded from the definition of IR, such as those even with an ER visit or hospitalization but without admitting diagnosis of the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity and allergic reactions. Thus, the rate of IRs requiring medical intervention might be underestimated. Second, as it is not feasible to completely capture all mild to moderate IRs based on claims data, the cost findings from this study may not be generalizable to IRs as a whole. Third, because this database did not contain actual dosing information for cetuximab, the study used the cetuximab payment amount as a proxy for change in dose. Dose reductions following the initial administration, however, were ignored because of standard loading-dose protocols for cetuximab. Fourth, this analysis was based on a database of commercially insured patient population; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to other populations. As described in the ‘Data Sources’ section, the population in the database is representative of the overall USA population with employer-sponsored health insurance, but it does not include patients who are uninsured or rely exclusively on government-sponsored health insurances. Nevertheless, over half of the patients in this study sample were 65 years or older; thus, they were also covered by USA Medicare—the USA federal government-sponsored health insurance program. Fifth, this analysis evaluated only the short-term direct clinical and economic impacts of IRs. There are likely additional indirect effects on patients and their caregivers that were not addressed in this study. Long-term clinical and economic implications for patient treatment and clinical practice were not investigated and warrant future research.

Despite these limitations, the database with a large patient population from geographically diverse health plans in real-world settings and the claims-based algorithm provide a valuable tool for research in identifying and quantifying clinical and economic impacts of IRs.

conclusions

The incidence of cetuximab-related IRs requiring medical intervention in real-world clinical practice may be two to three times higher than the rates of severe IRs reported in the product labeling and clinical trials. The clinical and economic impacts of these IRs are substantial, as they often require inpatient treatment and cause disruption of infusion or discontinuation of therapy.

funding

Amgen, Inc. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Amgen, Inc.

disclosure

PFW, BLB, VW, and ZZ are Amgen employees.

Figure 1.

Adjusted costs of cetuximab administrations by IR status. ER, emergency room; IR, infusion reaction.

appendix

Table A1.

Algorithm for identifying infusion reactions (IRs)

|

Table A2.

Results of generalized linear model for costs of infusion reactions (IRs)

| Independent variable | Coefficient | SE | P value |

| IRs requiring hospitalization or ER visit | 1.113 | 0.172 | 0.000 |

| IRs without hospitalization or ER visit | 0.321 | 0.082 | 0.000 |

| Male | 0.029 | 0.031 | 0.351 |

| Age | −0.009 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Geographic region | |||

| Northeast | 0.090 | 0.059 | 0.126 |

| North central | −0.003 | 0.046 | 0.940 |

| South (reference) | |||

| West | 0.018 | 0.047 | 0.698 |

| Urban location | 0.078 | 0.040 | 0.051 |

| Year of first infusion | |||

| 2004/2005 (reference) | |||

| 2006 | −0.013 | 0.029 | 0.643 |

| Type of health insurance | |||

| Comprehensive FFS (reference) | |||

| HMO | 0.178 | 0.063 | 0.005 |

| PPO | 0.207 | 0.058 | 0.000 |

| POS | 0.262 | 0.083 | 0.002 |

| Other | 0.100 | 0.059 | 0.091 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Deyo–Charlson comorbidity index | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| Colon (versus rectal) cancer | −0.019 | 0.034 | 0.572 |

| History of allergy | −0.002 | 0.044 | 0.967 |

| Concomitant platinum use | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.610 |

| First infusion | 0.367 | 0.030 | 0.000 |

| Model constant | 8.646 | 0.124 | 0.000 |

ER, emergency room; FFS, fee-for-service; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred provider organization; POS, point of service; SE, standard error.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Making treatment decisions: monoclonal antibodies 2009; http://www.cancer.org (10 November 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenz HJ. Management and preparedness for infusion and hypersensitivity reactions. Oncologist. 2007;12:601–609. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartzberg LS, Stepanski EJ, Fortner BV, et al. Retrospective chart review of severe infusion reactions with rituximab, cetuximab, and bevacizumab in community oncology practices: assessment of clinical consequences. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:393–398. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartzberg LS, Stepanski EJ, Walker MS, et al. Implications of IV monoclonal antibody infusion reaction for the patient, caregiver, and practice: results of a multicenter study. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:91–98. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0474-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Neil BH, Allen R, Spigel DR, et al. High incidence of cetuximab-related infusion reactions in Tennessee and North Carolina and the association with atopic history. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3644–3648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen RM, Goldberg RM, Berlin J, et al. Unusually high rates of hypersensitivity to cetuximab in the middle-southern United States: association with atopic phenotype. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(20 Suppl) 9051. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cetuximab Package Insert. http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2004/1250841bl.pdf (25 February 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Needle MN. Safety experience with IMC-C225, an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:55–60. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.35648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colwell HH, Mathias SD, Ngo NH, et al. The impact of infusion reactions on oncology patients and clinicians in the inpatient and outpatient practice settings: oncology nurses’ perspectives. J Infus Nur. 2007;30:153–160. doi: 10.1097/01.NAN.0000270674.13439.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang SP, Saif MW. Infusion-related and hypersensitivity reactions of monoclonal antibodies used to treat colorectal cancer—identification, prevention, and management. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung CH. Managing premedications and the risk for reactions to infusional monoclonal antibody therapy. Oncologist. 2008;13:725–732. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordstrom BL, Norman HS, Dube TJ, et al. Identification of abacavir hypersensitivity reaction in health care claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(3):289–296. doi: 10.1002/pds.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis JR, Martin C, Saag K, et al. Confirmation of administrative claims-identified opportunistic infections and other serious potential adverse events associated with tumor necrosis factor α antagonists and disease modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(2):343–346. doi: 10.1002/art.22544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]