The use of A1C for the identification of persons with undiagnosed diabetes has been investigated for a number of years (1–3). A1C better reflects long-term glycemic exposure than current diagnostic tests based on point-in-time measures of fasting and postload blood glucose (4,5) and has improved test-retest reliability (6). In addition, A1C includes no requirement for fasting or for the oral glucose tolerance test's 2-h wait. These advantages should lead to increased identification and more timely treatment of persons with diabetes. Recently, an American Diabetes Association (ADA)-organized international expert committee recommended the adoption of the A1C assay for the diagnosis of diabetes at a cut point of 6.5% (7). This cut point was primarily derived from a review of studies that examined the association of A1C values with incident retinopathy, and some of the most influential data were obtained from recently published prospective studies. Retinopathy was chosen as the ultimate criterion because it is among the main complications of diabetes. Identification of the point on the A1C distribution most closely related to future retinopathy will identify persons in the greatest need of interventions for the prevention of diabetes complications.

In addition to utility and convenience, A1C could help identify persons at increased risk of developing diabetes. This is an important public health priority since a structured lifestyle program or the drug metformin can reduce the incidence of diabetes by at least 50 and 30%, respectively (8). Ideally, selection of diagnostic cut points for pre-diabetes would be based on evidence that intervention, when applied to the high-risk group of interest, results not only in the prevention of diabetes but also later complications. However, currently there are no trials that can provide data to determine the ideal method for defining cut points. In the absence of such data, expert committees had to rely on information about the shape of risk curves for complications such as retinopathy. Previous expert committees assembled to address this issue have noted that there is no clear difference in retinopathy risk between different levels of impaired glucose tolerance (7). We are unaware of published prospective studies of adequate sample size or duration that have followed people in various pre-diabetic categories across the full span of time until complications developed. In the absence of informative trials (as well as prospective studies), the studies that measure A1C at baseline and incident diabetes may provide the definitions of high-risk states.

To better define A1C ranges that might identify persons who would benefit from interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes, we carried out a systematic review of published prospective studies that have examined the relationship of A1C to future diabetes incidence.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Data sources

We developed a systematic review protocol using the Cochrane Collaboration's methods (9). We formulated search strategies using an iterative process that involved medical subject headings and key search terms including hemoglobin A, glycated, predictive value of tests, prospective studies, and related terms (available from the authors on request). We searched the following databases between database establishment and August 2009: MEDLINE, Embase, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science (WOS), and The Cochrane Library.

Systematic searches were performed for relevant reviews of A1C as a predictor of incident diabetes. Reference lists of all the included studies and relevant reviews were examined for additional citations. We attempted to contact authors of original studies if their data were unclear or missing.

Study selection and data abstraction

We searched for published, English language, prospective cohort studies that used A1C to predict the progression to diabetes among those aged ≥18 years. We included studies with any design that measured A1C—whether using a cutoff point or categories—and incident diabetes. Titles and abstracts were screened for studies that potentially met inclusion criteria, and relevant full text articles were retrieved. X.Z. and W.T. reviewed each article for inclusion and abstracted, reviewed, and verified the data using a standardized abstraction template. If A1C measurement was standardized by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) and both standardized and unstandardized A1C values were reported, standardized values were used in the analyses. A sensitivity analysis, however, was conducted using both standardized and unstandardized A1C values. Relative measures of diabetes incidence including relative risk, odds ratio, hazard ratio, likelihood ratio, and incidence ratio were examined and cumulative incidences were converted to annual incidences (10). In studies reporting no measure of relative incidence, the incidence ratio was estimated as the absolute incidence in each A1C category divided by the incidence in the lowest A1C category.

Data analysis and synthesis

To summarize the relationship between A1C level and diabetes incidence over these studies, we modeled A1C as a function of annualized diabetes incidence using the aggregate study-level data. A1C was treated as an interval censored dependent variable, incidence as an independent variable, and study as an independent factor. Studies that stratified results by sex were treated as two separate studies. A1C, rather than diabetes incidence, was treated as the dependent variable because we were unaware of any method that supported interval censored independent variables; in many studies, A1C was categorized and thus was intrinsically censored. We used a Weibull distribution, which fit the data better than a normal or lognormal distribution (results not shown). Because we did not know the relationship's correct functional form, we fit a model with non-negative fractional polynomial terms, which can approximate many functional forms. We reported the relationship that was the mean over all studies and calculated pointwise 95% confidence limits for the curve. A sensitivity analysis to assess the lab-to-lab variation in A1C measurements was conducted and, to determine if any individual study substantially influenced our results, we refitted the curve, omitting data from each study one study at a time. Modeling was conducted using SAS (version 9.1.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) PROC LIFEREG.

RESULTS

Description of study participants

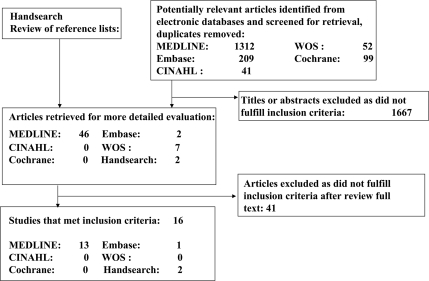

In total, 16 studies (11–26) fulfilled our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The reviewed studies included 44,203 total participants (range 27 to 26,563) and the follow-up interval averaged 5.6 years (range 2.8 to 12 years) (Table 1). Overall, the mean age among 15 studies reporting baseline age was 53.4 years (SD 7.2) (11–24,26). One study population was exclusively female (22) and another was exclusively male (24); other study populations were mixed and contained 69.0% female, on average. Mean baseline A1C and fasting plasma glucose among the studies were 5.2% (range 4.4 to 6.2%) and 5.4 mmol/l (range 5.1 to 5.7 mmol/l), respectively (11,14–16,19,21,24).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Citation | Sample size | Length of F/U (years) | Age at baseline (years) (means ± SD) | Sex (% female) | Race/ethnicity | Baseline A1C (%) (means ± SD) | Baseline FPG (mmol/l) (means ± SD) | Definition of incident diabetes | Inclusion criteria and sampling method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droumaguet 2006 | 2,820 | 6 | 47.3 (9.9) | 51.0 | French | 5.4 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.5) | FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l, or treatment by oral agents or insulin | Volunteers identified as nondiabetes or FPG < 7.0 mmol/l at baseline; persons with self-reported diabetes and FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| Edelman 2004 | 1,253 | 3 | 55.0 (6.0) | 6.0 | 69% white | 5.6 (0.7) | NR | FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l or A1C ≥ 7.0% or self-report | A convenience sample of patients without diabetes who visited clinics; patients with A1C ≥ 7.0% or FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| 29% black | |||||||||

| 2% other | |||||||||

| Hamilton 2007 | 27 | 6 | 60.2 (14.7) | 59.3 | NR | 5.6 (0.5) | NR | NR | All patients undergoing elective pancreatic surgery with A1C data and without diabetes |

| Inoue 2007 | 449 | 7 | 45.6 (6.6) | 23.8 | Japanese | 5.2 (0.5) | 5.1 (0.5) | FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l, or treatment by oral agents or insulin | All employees who participated in annual health screening; persons with self-reported diabetes or FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| Ko 2000 | 208 | 7 | 35.0 (7.7) | 87.5 | Chinese | 5.8 (0.8) | 5.4 (0.7) | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l | Randomly recruited from the patients without diabetes; patients with FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| Kolberg 2009 | 632 | 5 | 49.9 (1.7) | 38.4 | Danes | 6.0 (0.1) | 5.7 (0.2) | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l | Persons in an “at-risk” subpopulation of randomized sample aged ≥ 39 years, with BMI ≥ 25 and without diabetes; persons with FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| Lee 2002 | 504 | 4 | 56.0 (NR) | 67.3 | American Indians | Women: | Women: | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l | Indians who participated in the Strong Heart Study without diabetes at baseline; persons with 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT were excluded |

| 120: <5.1 | 193: <5.3 | ||||||||

| 98: 5.1–5.4 | 199: 5.3–5.7 | ||||||||

| 121: ≥5.5 | 193: ≥5.8 | ||||||||

| Men: | Men: | ||||||||

| 59: <5.2 | 185: <5.4 | ||||||||

| 50: 5.2–5.5 | 183: 5.4–5.8 | ||||||||

| 56: ≥5.6 | 179: ≥5.9 | ||||||||

| Little 1994 | 257 | 6.1 | 46.7 (12.0) | 66.9 | Pima Indians | 60%:<6.03% 40%:≥6.03% | NR | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.8 mmol/l | Residents who participated in a longitudinal epidemiological study; persons with 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or used insulin or oral agents were excluded |

| Narayan 1996 | 1,108 | 5 | 35.3 (9.8) | 63.1 | Pima Indians | 6.2 (0.6) | 5.4 (0.6) | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT | All residents aged 25–64 years without diabetes; persons with 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT were excluded |

| Hijpels 1996 | 158 | 3 | 64.2 (2.5) | 55.9 | Caucasian | Median (25th–75th per.) 5.5 (5.2–5.9) no-converters 5.7 (5.3–6.0) converters | Median (25th–75th per.) 5.9 (5.6–6.4) no-converters 6.1 (5.6–6.6) converters | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT | Persons with IGT randomly selected from the registry of Hoorn; persons with 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT were excluded |

| Norberg 2006 | 468 | 12 | 51.7 (7.6) | 40.4 | Sweden | 4.4 (0.3) | 5.5 (0.7) | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.8 mmol/l | Community population in the county of Vaesterbotten who participated in an intervention program; persons with 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT were excluded |

| Pradhan 2007 | 26,563 | 10.8 | 54.6 (7.1) | 100.0 | NR | 5.0 (0.4) | NR | Self-report | Randomized female health professional aged ≥ 45 years without diabetes and missing baseline BMI; persons with self-reported diabetes were excluded |

| Preiss 2,009 | 1,620 | 2.8 | 66.0 (12.0) | 32.7 | NR | 6.2 (0.7) | NR | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.8 mmol/l | Participants in CHARM without diabetes; persons with 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| Sato 2009 | 6,804 | 4 | 47.7 (4.2) | 0 | Japanese | 5.2 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.5) | FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l or treatment by oral agents | Participants aged 40–55 years with FPG < 7.0 mmol/l who did not take an oral agent or insulin; persons with FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| Shimazaki 2007 | 513 | 3 | Middle-aged | 52.4 | Japanese | NR | NR | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.8 mmol/l | Patients selected from the hospital information system; patients with 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| Yoshinaga 1996 | 819 | 5 | 52.3 (6.2) | 15.9 | Japanese | NR | NR | 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/l in an OGTT or FBG ≥ 6.7 mmol/l | Government officials and their spouses with A1C ≥ 6.2%, FBG ≥ 100 mg/dl, and positive urine sugar; persons with self-reported diabetes and FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l were excluded |

| Mean/Total | 44,203 | 5.6 | 53.4 (7.2) | 69.0 | 5.2 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.5) | |||

| Range | 27–26,563 | 2.8–12 | 35.0–66.0 | 0–100 | 4.4–6.2 | 5.1–5.7 |

CHARM, the Candesartan in Heart Failure-Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity; FBG, fasting blood glucose; F/U, follow-up; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NR, not reported; OGTT, oral glucose tolerant test; per., percentile; 2-h PG, 2-h plasma glucose.

Ten studies (11,12,14,18,20,21,23–26) reported that A1C was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography, three (15,19,22) used other methods, and three (13,16,17) did not provide information about A1C measurement. A1C values in three studies (11,24,25) were standardized by the NGSP, one (22) by the International Federation of Clinical Chemists, and another (21) by the Swedish MonoS Standard. The A1C values standardized by the Swedish MonoS Standard were very low and covered a very narrow range (4.5 to 4.7%) and we did not use data from this study for statistical modeling.

Incidence of diabetes associated with A1C levels

Among the eight studies that reported A1C categories (11,12,17,21,22,24–26) (Table 2), the range of A1C from 4.5 to 7.1% was associated with diabetes incidences ranging from 0.1% per year to 54.1% per year. In general, studies that categorized A1C across a full range of A1C values (11,12,17,22,24–26) showed that 1) risk of incident diabetes increased steeply across the A1C range of 5.0 to 6.5%; 2) both the relative and absolute incidence of diabetes varied considerably across studies; 3) the A1C range of 6.0 to 6.5% was associated with a highly increased risk of incident diabetes, frequently 20 or more times the incidence of A1C <5.0%); 4) the A1C range of 5.5 to 6.0% was associated with a substantially increased relative risk (frequently five times the incidence of A1C <5.0%); and 5) the A1C range of 5.0 to 5.5% was associated with an increased incidence relative to those with A1C <5% (about two times the incidence of A1C <5.0%).

Table 2.

A1C levels and incidence of diabetes

| Citation | A1C cut-off point (or category, or percentiles) % | Incidence (95% CI) % | Annualized incidence (95% CI) % | A1C category (or unit of increase in A1C) % | Relative risk (95% CI) (or OR, HR, LR, IR) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droumaguet 2006 | (From Figure 1A) | After stratifying on FPG, A1C predicted diabetes only in subjects with IFG (FPG ≥ 6.1 mmol/l). The OR for a 1% increase in A1C was 7.2 (95% CI, 3.0–17.0). A1C categories were incorrect on page 1,622. The correct ones are 4.5–5.0, 5.1–5.5, 5.6–6.0, and 6.1–6.5 (confirmed by authors) | ||||

| Women: | 6-year cumulative | Women: | ||||

| 5.3–5.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | ||||

| 5.8 | 5.0 | 0.9 | ||||

| 5.8–7.1 | 11.0 | 1.9 | <4.5 | OR (95% CI), ref. | ||

| Men: | 6-year cumulative | Men: | 4.5–5.0 | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | ||

| 5.3–5.7 | 2.6 | 0.4 | 5.1–5.5 | 1.5 (0.7–3.4) | ||

| 5.8 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 5.6–6.0 | 5.0 (2.0–12.8) | ||

| 5.8–7.1 | 11.5 | 2.0 | 6.1–6.5 | 32.7 (11.5–92.6) | ||

| Edelman 2004 | ≤5.5 | Annual, 0.8 (0.4–1.2) | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) | Obese patients with A1C 5.6 to 6.0 had an annual incidence of diabetes of 4.1% (95% CI, 2.2–6.0%) | ||

| 5.5–6 | Annual, 2.5 (1.6–3.5) | 2.5 (1.6–3.5) | ||||

| 6.1–6.9 | Annual, 7.8 (5.2–10.4) | 7.8 (5.2–10.4) | ||||

| (From Figure 2) | (From Figure 2) | (From Figure 2) | IR* | |||

| 5.1–5.5 | 0.9 (SEM, 0.5) | 0.9 (SEM, 0.5) | 1.0 | |||

| 5.6–6.0 | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.8 | |||

| 6.1–6.5 | 6.4 (2.5) | 6.4 (2.5) | 7.1 | |||

| 6.6–6.9 | 18.0 (12.0) | 18.0 (12.0) | NR | 20.0 | ||

| Hamilton 2007 | Baseline mean A1C for those with incident diabetes is 6.3 (0.7), and for nondiabetes is 5.2 (0.4) | |||||

| 6-year cumulative | ||||||

| 5.6 in baseline | 37.0 | 6.2 | NR | NR | ||

| Inoue 2007 | <5.8 with high NFG | Annual, 0.9 | 0.9 | FPG and A1C predicts incidence of diabetes, especially for those with FPG ≥ 5.55 mmol/l | ||

| ≥5.8 with high NFG | Annual, 3.3 | 3.3 | ||||

| <5.8 with IFG | Annual, 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.5% increase in A1C | OR (95%CI) | ||

| ≥5.8 with IFG | Annual, 9.5 | 9.5 | 3.0 (1.7–5.3) | |||

| Ko 2000 | LR | The calculation of annual incidence diabetes for category of A1C < 6.1 with FPG > 6.1 mmol/l is incorrect (44.1). The correct one is 54.1 (confirmed by authors) | ||||

| <6.1 with FPG <6.1 | Annual, 8.1 | 8.1 | <6.1 with FPG <6.1 | 0.6 | ||

| ≥6.1 with FPG <6.1 | Annual, 13.7 | 13.7 | ≥6.1 with FPG <6.1 | 0.9 | ||

| <6.1 with FPG ≥6.1 | Annual, 17.4 | 17.4 | <6.1 with FPG ≥6.1 | 1.1 | ||

| ≥6.1 with FPG ≥6.1 | Annual, 54.1 | 54.1 | ≥6.1 with FPG ≥6.1 | 9.3 | ||

| Kolberg 2009 | 5-year cumulative | Baseline mean A1C for those with incident diabetes is 6.1 (0.1), and for nondiabetes is 5.9 (0.1). No-converters were randomly selected in a 3:1 ratio to converters. We calculated incidence of diabetes using data from whole sample | ||||

| 6.0 in baseline | 5.7 | 1.2 | NR | NR | ||

| Lee 2002 | Women: | 4-year cumulative | Women: | Women: | IR | The overall 4-year incidence rate was 19.7% among 1,664 participants without diabetes in baseline, and average annual Incidence rate 4.9% |

| 120: <5.1 | 27.4 | 6.9 | 120: <5.1 | 1.0 | ||

| 98: 5.1–5.4 | 34.7 | 8.7 | 98: 5.1–5.4 | 1.3 | ||

| 121: ≥5.5 | 47.9 | 12.0 | 121: ≥5.5 | 1.7 | ||

| Men: | 4-year cumulative | Men: | Men: | IR | ||

| 59: <5.2 | 30.5 | 7.6 | 59: <5.2 | 1.0 | ||

| 50: 5.2–5.5 | 32.0 | 8.0 | 50: 5.2–5.5 | 1.0 | ||

| 56: ≥5.6 | 51.8 | 13.0 | 56: ≥5.6 | 1.7 | ||

| Little 1994 | 3.3-year cumulative | A1C was classified as either normal or elevated based on whether it was below or above the upper limit of the A1C normal range (6.03%) | ||||

| ≤6.03 with NGT | 9.7 | 2.9 | ||||

| >6.03 with NGT | 11.1 | 3.4 | ||||

| ≤6.03 with IGT | 27.7 | 8.4 | 1.0% difference in A1C | OR (95% CI) | ||

| >6.03 with IGT | 68.4 | 20.7 | 6.8 (1.8–25.8) | |||

| Narayan 1996 | 25th percentiles, 5.7 | 5-year cumulative | 25th percentiles, 5.7 | HR (95% CI) | The diabetes hazard rate ratio (95% CI) is 1.8 (1.5–2.1) as predicted by A1C percentiles of 25th and 75th. | |

| 75th percentiles, 6.7 | 13.5 | 1.6 | 75th percentiles, 6.7 | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | ||

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) | Median (25th–75th percentiles) | |||||

| 5.5 (5.2–5.9) for | 5.5 (5.2–5.9) for | |||||

| no-converters | no-converters | |||||

| Nijpels 1996 | 5.7 (5.3–6.0) for | 3-year cumulative | 5.7 (5.3–6.0) for | NR | The incidence density of diabetes was 13.8% per year (95% CI, 3.5–24.0). At baseline, 12% (n = 19) of subjects had A1C > 6.1% of whom 52.6% progressed to diabetes | |

| converters | 28.5 (15.0–42.0) | 9.5 | converters | |||

| Norberg 2006 | Mean time of 5.4+/−8.4 year cumulative | The combination of A1C, FPG, and BMI are effective for predicting risk of diabetes | ||||

| Women | Women | Women | ||||

| <4.5 | 18.1 | 3.4 | OR for women, ref. | |||

| 4.5–4.69 | 35.9 | 6.6 | <4.5 | |||

| ≥4.7 | 64.3 | 11.9 | 4.5–4.69 | 2.0 (0.5–8.9) | ||

| Men | Men | Men | ≥4.7 | 19.6 (2.5–152.4) | ||

| <4.5 | 15.3 | 2.8 | <4.5 | OR for men, ref. | ||

| 4.5–4.69 | 44.4 | 8.2 | 4.5–4.69 | 1.2 (0.3–5.3) | ||

| ≥4.7 | 73.2 | 13.6 | ≥4.7 | 16.0 (2.2–115.3) | ||

| Pradhan 2007 | <5.0 | Annual, 0.1 | 0.1 | <5.0 | RR (95%CI), ref. | For diabetes, an increase in risk was noted in each category above 5.0% in both age-adjusted and multivariable models and after exclusion of cases diagnosed with 2 years or even 5 years of follow-up |

| 5.0–5.4 | Annual, 0.5 | 0.5 | 5.0–5.4 | 4.1 (3.5–4.9) | ||

| 5.5–5.9 | Annual, 3.2 | 3.2 | 5.5–5.9 | 25.6 (21.1–30.8) | ||

| 6.0–6.4 | Annual, 9.1 | 9.1 | 6.0–6.4 | 76.7 (59.4–99.1) | ||

| 6.5–6.9 | Annual, 9.3 | 9.3 | 6.5–6.9 | 77.6 (51.4–117.4) | ||

| ≥7.0 | Annual, 22.7 | 22.7 | ≥7.0 | 201.4 (149.7–271.1) | ||

| Preiss 2,009 | 2.8-year cumulative | A1% increase in A1C | OR (95%) | Baseline mean A1C for those with incident diabetes is 6.8 (0.9), and for nondiabetes is 6.2 (0.7) | ||

| 6.2 (0.7) in baseline | 7.8 | 2.8 | 2.3 (1.9–2.8) | |||

| Sato 2009 | 4-year cumulative | Even after stratifying participants by FPG (≤ 99 or ≥ 100 mg/dl), elevated A1C had an increased risk of type 2 diabetes | ||||

| ≤5.3 | 3.0 | 0.7 | ≤5.3 | OR (95%), ref. | ||

| 5.4–5.7 | 6.5 | 1.6 | 5.4–5.7 | 2.3 (1.7–3.0) | ||

| 5.8–6.2 | 20.6 | 5.1 | 5.8–6.2 | 8.5 (6.4–11.3) | ||

| 6.3–6.7 | 41.9 | 10.5 | 6.3–6.7 | 23.6 (16.3–34.1) | ||

| ≥6.8 | 69.1 | 17.3 | ≥6.8 | 73.3 (41.3–129.8) | ||

| Shimazaki 2007 | 3-year cumulative | Total sample size is 38,628 with age range from 15 year above. Tables 3 and 4 reported a subgroup of middle-aged data | ||||

| <5.6 | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.1 | ||||

| 5.6–6.4 | 7.5 (3.6–15.7) | 2.5 | 5.6–6.4 | HR (95% CI), ref. | ||

| ≥6.5 | 30.8 (21.7–43.8) | 10.3 | ≥6.5 | 7.1 (4.6–10.9) | ||

| Yoshinaga 1996 | 5-year cumulative | IR* | The combination of A1C and OGTT enables more precise prediction of progression to diabetes in those with glucose intolerance | |||

| ≤6.3 | 5.4 | 1.1 | ≤6.3 | 1.0 | ||

| 6.4–6.7 | 20.3 | 4.1 | 6.4–6.7 | 3.7 | ||

| ≥6.8 | 52.1 | 10.4 | ≥6.8 | 9.5 |

*Incidence ratio (IR) was computed by the incidence in each A1C category divided by the incidence of the lowest A1C category. FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HR, hazard ratio; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; IR, incident ratio; LR, likelihood ratio; NFG, normal fasting glucose; NGT, normal glucose tolerance; NR, nor reported; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; OR, odds ratio; ref., reference; RR, relative risk.

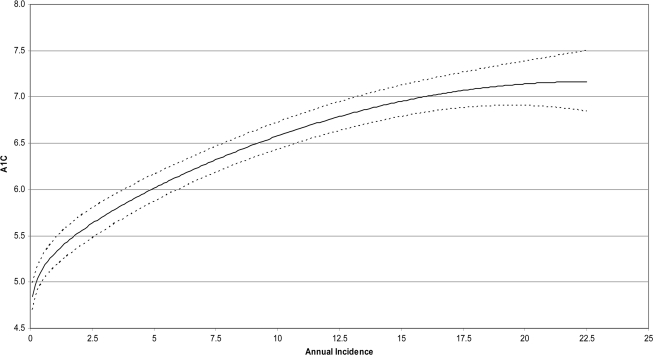

Using data from these seven studies (11,12,17,22,24–26), we modeled A1C as a function of diabetes incidence (Fig. 2). The curve demonstrated that A1C was positively associated with the incidence of diabetes with a change-in-slope occurring at an A1C level of about 5.5%. In other words, when diabetes incidence increased 0.3 to 1.8%, the A1C increased from 5.0 to 5.5%, or on average about a 0.33 percentage point increase in A1C per 1.0 percentage point increase in incidence. When diabetes incidence increased from 1.8 to 5.0%, the A1C increased from 5.5 to 6.0%, or about a 0.16 percentage point increase in A1C per 1.0 percentage point increase in incidence. Furthermore, when diabetes incidence increased from 5.0 to 9.5%, the A1C increased from 6.0 to 6.5%, or about a 0.11 percentage point increase in A1C per 1.0 percentage point increase in incidence. These associations convert to a 5-year incidence of <5 to 9% across A1C of 5.0 to 5.5%, 9 to 25% across the A1C range of 5.5 to 6.0%, and 25 to 50% across the A1C range of 6.0 to 6.5%. We noted that in one very large study (22) that used Kaplan-Meier curves to depict the relationship between time before developing diabetes and baseline A1C values, the curves appeared to diverge between A1C values of 5.0 to 5.4% and 5.5 to 5.9%.

Figure 2.

A1C modeled as a function of annualized incidence. The dashed lines are pointwise 95% confidence limits for the fitted curve.

Our sensitivity analyses showed that the omission of studies other than the Edelman study created little change in the curve. Omission of the Edelman study resulted in a biologically implausible curve. However, in the range of A1C/incidence discussed here, the difference between the curves with/without the Edelman study was small. Thus, while the Edelman study was highly influential in overall curve fitting, its impact on our study's conclusions was minor.

In addition to the studies examining a full range of A1C values, three additional studies (14,15,18) evaluated incidence above/below a dichotomous cut point in the 5.8 to 6.1% range. These studies demonstrated incidence estimates two to four times as great among the higher A1C groups and showed stronger associations between A1C and subsequent incidence among persons with impaired fasting glucose.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review of prospective studies confirms a strong, continuous association between A1C and subsequent diabetes risk. Persons with an A1C value of ≥6.0% have a very high risk of developing clinically defined diabetes in the near future with 5-year risks ranging from 25 to 50% and relative risks frequently 20 times higher compared with A1C <5%. However, persons with an A1C between 5.5 and 6.0% also have a substantially increased risk of diabetes with 5-year incidences ranging from 9 to 25%. The level of A1C appears to have a continuous association with diabetes risk even below the 5.5% A1C threshold, but the absolute levels of incidence in that group are considerably lower.

In light of recent interest in adopting A1C for the diagnosis of diabetes, these findings may be useful to guide policies related to the classification and diagnosis of persons at high risk of developing diabetes prior to preventive intervention. The progression of risk of diabetes with A1C is similar in magnitude and shape as previously described for fasting plasma glucose and 2-h glucose and suggests that A1C may have a similar application as an indicator of future risk (27). The ideal decision about what A1C cut point is used for intervention should ultimately be based on the capacity for benefit as shown in clinical trials. Our findings suggest that A1C range of 5.5 and 6.5% will capture a large portion of people at high risk, and if interventions can be employed to this target population, it may bring about significant absolute risk reduction. Given the current science and evidence of the cost-effectiveness of intensive interventions conducted in clinical trials (28,29), the use of a threshold somewhere between 5.5 and 6.0% is likely to ensure that persons who will truly benefit from preventive interventions are efficiently identified. It is also reassuring that the mean A1C values of the populations from the Diabetes Prevention Program, the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study, and the Indian Diabetes Prevention Program, wherein the mean A1C was 5.8 to 6.2% and SDs of at least 0.5 percentage points, span the range from 5.5 to 6.5% (28–30).

There was considerable variation in the estimates of relative risk and absolute incidence across studies stemming from several factors. First, there was considerable variation in the populations studied ranging from relatively young women (15) to older men (23). Second, the magnitude of relative risk is highly dependent upon the overall risk of the population and the selection of the referent group; studies with low absolute risk and the selection of a particularly low-risk referent group will have very high relative risks across the spectrum of A1C. Third, there was variation in the outcome definition with almost all studies using fasting glucose of 7.0 mmol/l as the definition of diabetes, but only approximately half of the studies using the oral glucose tolerance test. Fourth, there is likely to be some variation in relative risk because of variation in the calculation of risk statistics; studies reported relative risks, odds ratios, and incidence ratios, and simple presentations of incidence. Since we lacked original data, we were unable to optimally convert and standardize risk estimates across groups. Fifth, A1C assays vary across laboratories. As indicated above, A1C measurement was standardized by NGSP only in three studies (11,24,25), and only one study (24) reported both standardized and unstandardized A1C values. When we conducted a sensitivity analysis in our modeling A1C as a function of incidence using both standardized and unstandardized A1C values from one study (24), there was the maximum likelihood that continuous curves did not show any significant difference. Finally, there was variation in the choice of cutoff points that may have influenced the conclusions. Several studies presented in our review were not suitable for modeling because they did not examine incidence of diabetes across a broad range of A1C values. However, the conclusions from these additional studies were generally consistent with those that examined multiple A1C categories. For example, studies by Ko et al. (15), Inoue et al. (14), and Little et al. (18) used dichotomous cut points of 5.8, 6.1, and 6.0, respectively, and found that persons above the threshold had roughly three times the incidence of those below the cutoff point.

Several studies found that A1C is particularly predictive of future diabetes after prior stratification of fasting plasma glucose (11,14,21,24,26). This is consistent with prior observations that elevated fasting and 2-h glucose in combination indicates greater risk than either fasting plasma glucose or A1C alone. This improved predictability may be a function of reducing error variance; in other words, conducting a follow-up test clarifies the group with more stable hyperglycemia, and is the main reason that a second test is recommended for a full clinical diagnosis.

Our most important limitation was the lack of original data to model the continuous association between A1C values and incidence. This lack of original data required us to use a modeling approach with which many readers are unfamiliar. Nevertheless, our modeling of average studies resulted in an average incidence value of roughly 1% per year for persons with normal A1C values, an incidence estimate that is consistent with numerous other estimates of the general population. The lack of access to raw data also prevented us from conducting formal ROC analyses of A1C cut-off points to distinguish between eventual cases/noncases or to quantitatively assess the impact of variation in population characteristics on the relationship between A1C and incidence. Our findings could also be influenced by the choice of outcome definition. A1C is more apt to predict diabetes if the outcome is also A1C-based. We did not detect major differences in the A1C/diabetes incidence association according to the choice of glycemic test. Since identifying A1C to predict diabetes defined by glycemic indicators is ultimately circular, future studies should examine the relationship of glycemic markers and later diabetes risk by using several glycemic markers to define incident diabetes, as well as to consider morbidity outcomes.

The growth of diabetes as a national and worldwide public health problem, combined with strong evidence for the prevention of type 2 diabetes with structured lifestyle intervention and metformin, have placed a new importance on the efficient determination of diabetes risk. The selection of specific thresholds, however, will ultimately depend on the interventions likely to be employed and the tradeoffs between sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value. These findings support A1C as a suitably efficient tool to identify people at risk and should help to advance efforts to identify people at risk for type 2 diabetes for referral to appropriate preventive interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1. Forrest RD, Jackson CA, Yudkin JS: The glycohaemoglobin assay as a screening test for diabetes mellitus: the Islington Diabetes Survey. Diabet Med 1987; 4: 254–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Little RR, England JD, Wiedmeyer HM, McKenzie EM, Pettitt DJ, Knowler WC, Goldstein DE: Relationship of glycosylated hemoglobin to oral glucose tolerance: implications for diabetes screening. Diabetes 1988; 37: 60–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Modan M, Halkin H, Karasik A, Lusky A: Effectiveness of glycosylated hemoglobin, fasting plasma glucose, and a single post load plasma glucose level in population screening for glucose intolerance. Am J Epidemiol 1984; 119: 431–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nathan DM, Turgeon H, Regan S: Relationship between glycated haemoglobin levels and mean glucose levels over time. Diabetologia 2007; 50: 2239–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, Zheng H, Schoenfeld D, Heine RJ. A1c-Derived Average Glucose Study Group. Translating the A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 1473–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selvin E, Crainiceanu CM, Brancati FL, Coresh J: Short-term variability in measures of glycemia and implications for the classification of diabetes. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 1545–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. International Expert Committee. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1327–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crandall JP, Knowler WC, Kahn SE, Marrero D, Florez JC, Bray GA, Haffner SM, Hoskin M, Nathan DM. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The prevention of type 2 diabetes. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2008; 4: 382–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarke M, Oxman AD: Cochrane Reviewers Handbook. Oxford, U.K., Update Software, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox DR, Oakes D: Analysis of Survival Data. London, Chapman & Hall, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Droumaguet C, Balkau B, Simon D, Caces E, Tichet J, Charles MA, Eschwege E. DESIR Study Group. Use of HbA1c in predicting progression to diabetes in French men and women: data from an Epidemiological Study on the Insulin Resistance Syndrome (DESIR). Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1619–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Edelman D, Olsen MK, Dudley TK, Harris AC, Oddone EZ: Utility of hemoglobin A1c in predicting diabetes risk. J Gen Intern Med 2004; 19: 1175–1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamilton L, Rohan JD: Hemoglobin A1c can be helpful in predicting progression to diabetes after Whipple procedure. HPB (Oxford) 2007; 9: 26–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inoue K, Matsumoto M, Kobayashi Y: The combination of fasting plasma glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin predicts type 2 diabetes in Japanese workers. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007; 77: 451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ko GT, Chan JC, Tsang LW, Cockram CS: Combined use of fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c predicts the progression to diabetes in Chinese subjects. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 1770–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kolberg JA, Jørgensen T, Gerwien RW, Hamren S, McKenna MP, Moler E, Rowe MW, Urdea MS, Xu XM, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Borch-Johnsen K: Development of a type 2 diabetes risk model from a panel of serum biomarkers from the Inter99 cohort. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1207–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee ET, Welty TK, Cowan LD, Wang W, Rhoades DA, Devereux R, Go O, Fabsitz R, Howard BV: Incidence of diabetes in American Indians of three geographic areas: the Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Little RR, England JD, Wiedmeyer HM, Madsen RW, Pettitt DJ, Knowler WC, Goldstein DE: Glycated haemoglobin predicts progression to diabetes mellitus in Pima Indians with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetologia 1994; 37: 252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Narayan KM, Hanson RL, Pettitt DJ, Bennett PH, Knowler WC: A two-step strategy for identification of high-risk subjects for a clinical trial of prevention of NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1996; 19: 972–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nijpels G, Popp-Snijders C, Kostense PJ, Bouter LM, Heine RJ: Fasting proinsulin and 2-h post-load glucose levels predict the conversion to NIDDM in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance: the Hoorn Study. Diabetologia 1996; 39: 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Norberg M, Eriksson JW, Lindahl B, Andersson C, Rolandsson O, Stenlund H, Weinehall L: A combination of HbA1c, fasting glucose and BMI is effective in screening for individuals at risk of future type 2 diabetes: OGTT is not needed. J Intern Med 2006; 260: 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pradhan AD, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM: Hemoglobin A1c predicts diabetes but not cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic women. Am J Med 2007; 120: 720–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Preiss D, Zetterstrand S, McMurray JJ, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Granger CB, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA, Gerstein HC, Sattar N. Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity Investigators. Predictors of development of diabetes in patients with chronic heart failure in the Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) program. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 915–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato KK, Hayashi T, Harita N, Yoneda T, Nakamura Y, Endo G, Kambe H: Combined measurement of fasting plasma glucose and A1C is effective for the prediction of type 2 diabetes: the Kansai Healthcare Study. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 644–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shimazaki T, Kadowaki T, Ohyama Y, Ohe K, Kubota K: Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) predicts future drug treatment for diabetes mellitus: a follow-up study using routine clinical data in a Japanese university hospital. Transl Res 2007; 149: 196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoshinaga H, Kosaka K: High glycosylated hemoglobin levels increase the risk of progression to diabetes mellitus in subjects with glucose intolerance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1996; 31: 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gerstein HC, Santaguida P, Raina P, Morrison KM, Balion C, Hunt D, Yazdi H, Booker L: Annual incidence and relative risk of diabetes in people with various categories of dysglycemia: a systematic overview and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007; 78: 305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, Mukesh B, Bhaskar AD, Vijay V. Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme (IDPP). The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1). Diabetologia 2006; 49: 289–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]