Abstract

Social group housing of rhesus macaques at biomedical facilities is advocated to improve the psychologic wellbeing of these intelligent and social animals. An unintended outcome of social housing in this species is increased intraspecific aggression resulting in cases of severe multiple trauma and posttraumatic shock. The metabolic correlates of oxygen debt are likely important quantifiers of the severity of posttraumatic shock and may serve as useful guides in the treatment of these cases. The purpose of this retrospective study was to evaluate venous blood lactate, base excess, bicarbonate, and pH as predictors of mortality. These 4 variables were assessed in 84 monkeys with severe traumatic injury and shock. Data were available from blood samples collected prior to resuscitation therapy and the day after resuscitation therapy. The pre- and postresuscitation therapy levels of the variables then were tested for association with 6-d survival. When measured prior to resuscitation therapy, all variables were strongly correlated with each other and had a statistically significant association with survival. No single variable had both strong specificity and high sensitivity when measured prior to resuscitation therapy. Survival analysis showed that as the number of categorical indicators of acidosis increased, 6-d survival decreased. Analysis of the 4 variables after resuscitation therapy indicated that lactate was the only variable significantly associated with survival in our study.

Many research facilities maintain populations of rhesus macaques in group housing that allows them to engage in social behaviors that are normal for the species, such as grooming, play, and huddling with conspecifics.21 An unintended consequence of social housing is intraspecific aggression. The trauma, specifically crush injuries from multiple bite wounds to the limbs and face, that may result from this aggression can be severe and often leads to significant morbidity and mortality if ignored or poorly treated.17 Major multiple trauma injuries result in sudden physical and metabolic alterations that can progress to organ dysfunction, organ failures, and even death. In addition to multiple severe skin wounds, the hemorrhage and obligatory edema that occur within the injured soft tissues have significant effect on circulating blood volume, resulting in intravascular volume depletion and hypovolemic shock. The associated decreased organ perfusion and impaired oxygen delivery result in regional hypoxia and anaerobic metabolism. The end-products of anaerobic metabolism are 2 ATP molecules and pyruvate, which is converted to lactic acid. Prolonged and severe tissue hypoperfusion results in the generation of large quantities of hydrogen ions (H+) from lactic acid, resulting in metabolic acidosis.2,9

Serum markers of metabolic acidosis may be measured as part of the critical care diagnostic plan to assess the severity of injury, determine treatment efficacy, and provide prognostic information. The most common of these markers include lactate, base excess (or base deficit), bicarbonate, and pH. Technologic advances in point-of-care testing have made rapid laboratory assessment of these markers accurate, practical, and affordable for veterinary medical facilities. However, no studies to date have validated markers of metabolic acidosis as predictors of mortality in rhesus macaques. Nor has the significance of these values been examined when used in combination or when they provide conflicting data.

Lactate, an end product of anaerobic metabolism, can be measured directly by many point-of-care analyzers. As calculated by most point-of-care analyzers, base excess is determined by using measured carbon dioxide, pH, and serum bicarbonate values and represents the concentration of titratable base minus the concentration of titratable acid needed to normalize the pH of a liter of blood to physiologic levels. A decreased base excess is thought to represent the presence of unmeasured anions. In acute trauma cases, the primary unmeasured anion is assumed to be lactate.4 Therefore, base excess usually is viewed as a surrogate marker for lactic acidosis.9,11 Bicarbonate is a buffer for serum hydrogen ions released during anaerobic metabolism. As metabolic acidosis worsens, bicarbonate levels decrease. In humans, bicarbonate and base excess are strongly correlated.8,10 Compared with lactate, base excess, and bicarbonate, serum pH is less clinically relevant for assessing metabolic acidosis in human patients.6,9,19 This difference most likely is due to the extensive compensatory physiologic mechanisms in place to maintain normal pH. pH is a direct measure of acidemia, whereas lactate, base excess, and bicarbonate are common means of characterizing acidosis.9

Multiple studies have been published in the human medical literature that validate the ability of lactate, base excess, bicarbonate, and pH for predicting morbidity and mortality among trauma and surgical patients.12,14,20,23 However, no single value has proven superior to the others in these regards,9 and the validity of these measurements has not been demonstrated in nonhuman primates. Several human studies have noted the predictive value of the initial lactate level.1,3,16 Other studies have demonstrated outcome is better predicted by other variables22 or have shown no correlation between lactate level and mortality.13

During hospitalization, the validity of these markers may be confounded by the rapid intravenous infusion of large volumes of resuscitation fluids and electrolytes administered to increase circulatory volume in shock patients. The confounding affects of shock therapy are important because these markers of metabolic acidosis frequently are used by clinicians to guide resuscitation. For example, the administration of large quantities of exogenous lactate (massive infusion of lactated Ringers solution) has been shown to increase lactate to levels significantly greater than those expected to result from the shock process alone.7,18 However, this elevation of lactate is transient and not associated with acidosis, because the end products of lactate metabolism are bicarbonate and glucose.7,24 In addition, the administration of sodium bicarbonate during resuscitation likely would confound the utility of bicarbonate measurements. The administration of sodium bicarbonate would similarly confound the utility of base excess as an endpoint for resuscitation, because bicarbonate is used in the calculation of base excess.

For the past 7 y, serial measurements of these systemic markers of metabolic acidosis have been used to guide the need for and response to resuscitation of nonhuman primate cases at our institution, the Oregon National Primate Research Center. Although the human medical literature and our experience in practice indicate that these measurements are valuable for case management, no previous scientific studies have validated them as indicators of morbidity or mortality in nonhuman primates. The purpose of this retrospective study was to evaluate venous blood lactate, base excess, bicarbonate, and pH values, obtained before and after treatment of shock, as predictors of 6-d mortality after trauma in rhesus macaques.

Materials and Methods

The subjects were 84 (28 male and 56 female )Indian-origin rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) housed at the AAALAC-accredited Oregon National Primate Research Center. Subjects presented between 01 October 2002 and 01 April 2009 for hypovolemic shock associated with multiple severe traumatic injuries. The demographics of the study population are given in Table 1. Prior to hospitalization, the macaques were housed in social groups of 30 to 175 animals in covered outdoor enclosures or open 1-acre enclosures. The outdoor enclosures had several structures on which the animals may play and climb, along with indoor areas into which animals may go for shelter. Animal care staff monitored all animal areas each morning to check specifically for injured or sick animals. In addition, macaques were observed throughout the day by veterinary and animal behavior staff as well as the animal care staff during their feeding and cleaning routines. Animals needing medical attention were admitted to the hospital for treatment. During hospitalization, animals were singly housed in standard monkey cages on a 12h:12-h light:dark cycle, with lights-on from 0700 to 1900 h, and at a constant temperature of 24 °C. Laboratory diet was provided twice daily, supplemented with fresh fruits and vegetables and drinking water ad libitum. All housing and care were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Oregon National Primate Research Center. All injuries sustained by subjects were the result of intraspecific aggression within social groups.

Table 1.

Case demographics

| n (%) | |||||

| Subjects | |||||

| Total study | 84 (100%) | ||||

| Male | 28 (33%) | ||||

| Female | 56 (67%) | ||||

| Mortality (within 6 d) | 28 (33%) | ||||

| Demographic | Mean ± 1 SD | 95% Confidence interval | Range | Skewnessa | |

| Age, y | 6.1 ± 3.6 | 5.3, 6.9 | 0.7 to 17.0 | 0.90 | |

| Admission pH | 7.36 ± 0.12 | 7.34, 7.39 | 6.90 to 7.53 | −0.65 | |

| Admission bicarbonate, mmol/L | 22.9 ± 5.6 | 21.7, 24.1 | 3.0 to 34.0 | −1.44 | |

| Admission base excess, mEq/L | −1.63 ± 6.85 | −3.11, –0.14 | −23.0 to 11.0 | −0.46 | |

| Median (interquartile range) | Range | Skewness | |||

| Admission lactate, mmol/L | 3.42 (1.76, 5.05) | 0.51 to 15.7 | 1.70b | ||

Skewness is assessed in survivors to avoid the confounding effect of different distributions in survivor classes.

Kolmogorov–Smironov test for normality P < 0.05 in both survivors and nonsurvivors.

Treatment for hypovolemic shock associated with traumatic injury was standardized for subjects. Upon admission to the intensive care unit, animals typically were sedated with ketamine HCl (approximately 8 mg/kg IM; Ketaved, Bioniche Teoranta, Inverin, Ireland), if sedation was necessary for handling. Veterinary examination was performed, and a venous blood sample was collected for point-of-care analysis (iSTAT, Abbott Point of Care, Princeton, NJ). Lactate, base excess, bicarbonate, and pH of the sample were measured and recorded in the patient record.

The clinical signs of hypovolemic shock associated with severe soft tissue injury were easily recognizable to clinicians. Once hypovolemic shock was diagnosed, point-of-care blood analysis was performed, an intravenous catheter was placed in a peripheral vein, and aggressive fluid therapy was initiated. A standardized dose of 30 mL/kg hourly crystalloid (lactated Ringers Solution) was infused for 3 h. Sodium bicarbonate (1 mEq/kg hourly) was added to the fluids being administered if base excess was less than –10 mEq/L; sodium bicarbonate (1 mEq/kg) was administered as an intravenous bolus when base excess was less than –15 mEq/L and pH was less than 7.1. In addition, hypothermia and hypoglycemia (if present) were treated, analgesic medications were administered, wounds were cleaned, and antibiotics were administered. After 3 h of fluid therapy, patients were reassessed (perhaps including follow-up point-of-care blood work) for clinical improvement. If a patient appeared stable, the patient was placed into an ICU observation cage overnight with supplemental heat. The next morning, patients were sedated, examined, and follow-up blood work was assessed. Depending on the time of day a patient presented and the ICU staffing and workload, the timing and frequency of posttreatment blood work may have varied between patients.

Acid–base parameters other than pO2 may be evaluated by using either arterial or mixed-venous samples.15 In most emergent patients, venous blood is faster and easier to obtain. For this reason, all blood samples in this study were obtained from peripheral veins. Venous lactate, base excess, bicarbonate, and pH were measured simultaneously on admission. These data were used in the preresuscitation analysis (analysis 1). In addition, all available posttreatment measurements of these variables were collected for the 84 subjects. Of the 73 animals that survived the first 24 h, complete data for parameters of acidosis the morning after initial shock therapy (that is, 14 to 18 h after cessation of initial fluid therapy) were available for 42 animals. These data were used in the postresuscitation analysis (analysis 2).

Normal ranges that were used for the parameters evaluated in this study were: lactate, 0 to 2.0 mmol/L; pH, 7.35 to 7.45; bicarbonate, 15 to 23 mmol/L; and base excess, –2 to 3 mEq/L. Any measured acid–base value falling outside of these normal ranges in the direction of acidosis (that is, lactate greater than 2.0 mmol/L; pH less than 7.350; bicarbonate less than 15 mmol/L; or base excess less than –2 mEq/L) was categorized as an ‘indicator of acidosis.’ A cutoff of 6 d defined survival in this study. The choice of 6 d was made based on past data as well as the distribution of survival times: 28 animals died within 6 d of admission; 1 died due to causes unrelated to trauma 37 d after admission; and the remaining 55 animals survived longer than 6 mo (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of subjects in the study.

Except for lactate values, markers of metabolic acidosis in survivors and nonsurvivors were compared by using Student t tests. Lactate values were not normally distributed and could not be transformed. For these reasons, lactate values were compared by using Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests, and correlations were tested by using Spearman rank correlations. Differences in the proportions of male and female subjects in the survivors and nonsurvivors were evaluated by using the Pearson χ2 test. Alpha values for significance were set at 0.05. To maximize the power of the study, the association of the acidosis parameters with survival time was analyzed by using Cox proportional hazards regression.5 Statistical analysis was performed by using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The cumulative survival graphs were constructed in SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Analysis 1: Parameters of acidosis prior to resuscitation therapy.

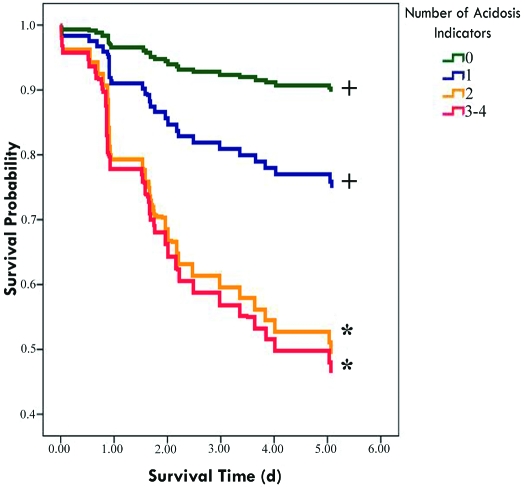

Demographic and acid–base data collected at admission for survivors (n = 56) and nonsurvivors (n = 28) are presented in Table 2. At this pretreatment time point, all of the acid–base parameters assessed (lactate, base excess, bicarbonate, and pH) were significantly associated with survival. All 4 parameters were strongly correlated with each other. Base excess, pH, and bicarbonate levels were positively correlated with each other (Table 3); lactate levels were negatively correlated with these variables. No single pretreatment parameter had both strong specificity and high sensitivity (Table 4). The lack of any indicator of acidosis had a high negative predictive value, whereas the presence of all 4 indicators of acidosis had 100% positive predictive value of mortality in this data set (Table 4). When the indicators of acidosis were evaluated categorically, cases with more indicators of acidosis had significantly (P < 0.05) lower probability of survival: multiple-trauma cases with no indicators of acidosis had a 90% probability of survival; cases with at least one indicator of acidosis had a 59% probability of survival; and cases with 2 or more indicators of acidosis had a 47% probability of survival (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of pretreatment acid–base variables in survivors and nonsurvivors

| Variable | Survived 6 d | Died before 6 d | P |

| No. of macaques | 56 | 28 | |

| Age | 5.88 ± 3.04 | 6.57 ± 4.52 | 0.4661b |

| Sex, male:female | 19:37 | 9:19 | 0.8700c |

| pH | 7.39 ± 0.09 | 7.29 ± 0.16 | 0.0032b |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L | 24.26 ± 5.24 | 20.14 ± 5.44 | 0.0012b |

| Base excess, mEq/L | 0.27 ± 5.41 | −5.43 ± 6.33 | 0.0014b |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 2.77 (1.43–4.30) | 4.66 (2.85–6.31) | 0.0025d |

Data represent mean ± 1 SD except where noted.

Median and interquartile ranges.

Student t test

Pearson χ2 test

Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test

Table 3.

Spearman rank-correlation coefficients of pretreatment acid–base variables

| Lactate | pH | Base excess | Bicarbonate | |

| pH | −0.58 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 0.65 |

| Base excess | −0.49 | 0.74 | 1.00 | 0.88 |

| Bicarbonate | −0.42 | 0.65 | 0.88 | 1.00 |

All correlations are statistically significant at P < 0.0001.

Table 4.

Value of pretreatment acid–base variables in predicting mortality after multiple trauma in rhesus macaques

| % Positive |

Predictive value |

Cox regression |

||||||||

| Parameter | n | Survivors | Nonsurvivors | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive | Negative | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | Type 3 P (Wald) | |

| Lactate > 2.0 mmol/L | 59 | 60.7 | 89.3 | 0.89 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.88 | 4.2 (1.5–18) | 0.0185 | |

| pH < 7.35 | 29 | 25.0 | 53.6 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 2.6 (1.3–5.7) | 0.0104 | |

| Bicarbonate < 15.0 mmol/L | 6 | 3.6 | 14.3 | 0.14 | 0.96 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 2.9 (0.9–7.6) | 0.0470 | |

| Base excess < –2 mEq/L | 32 | 26.8 | 60.7 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 3.1 (1.5–6.8) | 0.0037 | |

| Categorical acidosis indicators | ||||||||||

| 1 or more | 64 | 67.9 | 92.9 | 0.93 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.90 | 4.6 (0.98–82) | 0.1340 | |

| 2 or more | 36 | 30.4 | 67.9 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.81 | 5.0 (2.1–15) | 0.0011 | |

| 3 or more | 22 | 17.9. | 42.9 | 0.43 | 0.82 | 0.55 | 0.74 | 2.9 (1.3–5.9) | 0.0066 | |

| 4 or more | 4 | 0 | 14.3 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 6.6 (1.9–17) | 0.0006 | |

Figure 2.

Negative association of increasing numbers of pretreatment indicators of acidosis with 6-d survival in rhesus macaques. The lines indicate probability of survival at the time indicated. Because the study was stopped at 6 d, the probability of survival at 6 days is not estimatable, and the graph lines terminate at the last death prior to 6 d. Categorical indicators of venous acidosis: lactate, greater than 2 mmol/L; pH, less than 7.35; base excess, less than –2 mEq/L; or bicarbonate less than 15 mmol/L. *, Differences from 0 indicators significant at P < 0.02. +, Differences from 4 indicators significant at P < 0.05.

Analysis 2: Parameters of acidosis after initial resuscitation therapy.

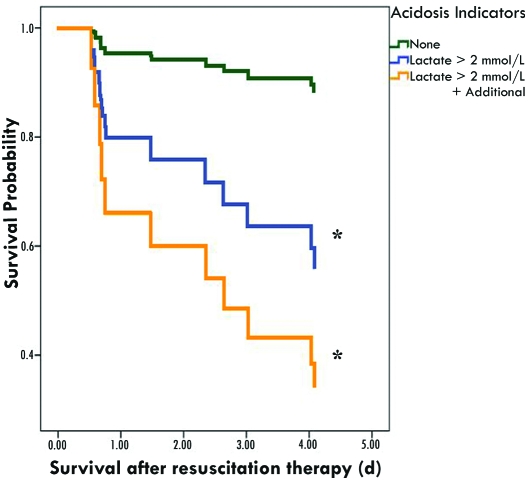

Postresuscitation data from macaques that survived the first 24 h was available for 42 animals. Lactate was the only acid–base parameter measured after initial resuscitation therapy that was significantly (P< 0.05) different between survivors (n = 31) and nonsurvivors (animals that survived at least 24 h but not 6 d; n = 11; Table 5). Unlike the results obtained at the preresuscitation therapy time point, lactate did not correlate with the other acid–base parameters postresuscitation therapy (Table 6). In addition, the correlations between pH, base excess, and bicarbonate were lower than those observed prior to resuscitation therapy. Lactate was the only postresuscitation therapy parameter significantly (P< 0.05) associated with survival (Table 7). Although the survival probability in animals with elevated posttreatment lactate and an additional indicator of acidosis was not significantly different from that in macaques with elevated posttreatment lactate and no other indicators of acidosis, the trend for decreased probability of survival with increasing indication of acidosis was significant (P = 0.03; Figure 3).

Table 5.

Comparison of posttreatment parameters in survivors and nonsurvivors

| Variable | Survived 6 d | Died before 6 d | P |

| No. of macaques | 31 | 11 | |

| Age, y | 5.92 ± 2.87 | 5.29 ± 3.29 | 0.5509 |

| Sex, male:female | 10:21 | 3:8 | 1.000 |

| pHa | 7.41 ± 0.04 | 7.41 ± 0.08 | 0.8079 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/La | 25.7 ± 5.9 | 26.9 ± 6.5 | 0.5825 |

| Lactate, mmol/Lb | 1.55 ± 0.67 | 2.60 ± 1.19 | 0.0044 |

| Base excess, mEq/La | 2.68 ± 4.83 | 2.81 ± 7.47 | 0.5309 |

Analysis was limited to macaques that survived at least 24 h and had complete posttreatment data.

Maximum for each subject obtained during first 24 h posttreatment.

Minimum for each subject obtained during first 24 h posttreatment.

Table 6.

Spearman rank-correlation coefficients of posttreatment venous acidosis parameters

| Lactate | pH | Base excess | Bicarbonate | |

| pH | −0.142 | 1.00 | 0.438b | 0.302a |

| Base excess | −0.004 | 0.438b | 1.00 | 0.856b |

| Bicarbonate | 0.047 | 0.302a | 0.856b | 1.00 |

Statistically significant at P < 0.05

Statistically significant at P < 0.002

Table 7.

Value of posttreatment acid–base variables in predicting mortality after multiple trauma in rhesus macaques

| % Positive |

Predictive value |

Cox regression |

|||||

| Parameter | n | Survivors | Nonsurvivors | Positive | Negative | Hazard ratio (95% Confidence interval) | Type 3 P value (Wald) |

| Lactate > 2.0 | 16 | 25.8 | 72.7 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 5.7 (1.6–26) | 0.0104 |

| Other indicator of acidosis | 9 | 19.4 | 27.3 | 0.33 | 0.76 | 1.6 (0.4–5.6) | 0.4793 |

| Lactate plus other indicator | 5 | 6.5 | 27.3 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 4.4 (1.0–15) | 0.0299 |

Figure 3.

Negative association of posttreatment indicators of acidosis with survival in rhesus macaques. The lines indicate probability of survival at the post therapy time indicated. Because the study was stopped at 5 d post therapy (6 d post trauma), the probability of survival at 5 d post therapy cannot be estimated, and the graph lines terminate at the last death prior to 5 d. Categorical indicators of venous acidosis: pH, less than 7.35; base excess, less than –2 mEq/L; or bicarbonate less than 15 mmol/L. *, Differences from 0 indicators significant at P < 0.05.

In all, 73 of the 84 macaques survived at least 24 h after resuscitation. The 31 macaques that survived the first 24 h but are missing postresuscitation data had significantly (P< 0.05) different preresuscitation values from the 42 animals with data (Table 8). Specifically, the animals without follow-up data had higher pH, higher base excess, and lower lactate values at admission. This finding suggests that for the group of 31 animals missing postresuscitation data, attending veterinarians chose to not reevaluate acid–base values the next day because initial acid–base values were normal (or near-normal).

Table 8.

Comparison of pretreatment parameters in survivors with complete and incomplete posttreatment acidosis assessment

| Variable | Complete posttreatment acidosis measurements | Incomplete posttreatment acidosis measurements | P |

| No. of macaques | 42 | 31 | |

| Age | 5.75 ± 2.95 | 6.25 ± 3.92 | 0.5565 |

| Sex, male:female | 11:20 | 13:29 | 0.6387 |

| Pretreatment pH | 7.34 ± 0.12 | 7.41 ± 0.07 | 0.0005 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L | 24.3 ± 6.1 | 22.4 ± 5.1 | 0.1593 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 4.91 ± 2.99 | 2.28 ± 1.52 | <0.0001 |

| Base excess, mEq/L | −2.52 ± 6.82 | 1.00 ± 5.54 | 0.0212 |

Analysis was limited to macaques that survived at least 24 h. Data are provided as mean ± 1 SD.

Discussion

Group-housed rhesus macaques that present to the veterinary ICU with multiple traumatic injuries typically suffer lacerations and multiple bite wounds from conspecifics. These wounds can be quite severe and result in systemic vasodilatory shock, in which oxygen delivery to tissues is restricted by low flow. The presence and extent of oxygen debt to tissues is difficult to measure directly and impossible to measure in a noninvasive manner.19 For these reasons, the currently predominant means of assessing cellular oxygen utilization and perfusion is the measurement of systemic markers of metabolic acidosis. These metabolic endpoints (serum pH, base excess, lactate, and bicarbonate) are useful indicators of the severity of shock as well as the adequacy of resuscitation. These parameters may be measured quickly and easily in the ICU by using relatively inexpensive handheld devices.

This study demonstrated that all 4 acid–base variables measured prior to initiation of shock therapy were associated with survival and were strongly correlated with each other at this time point. Although each of these preresuscitation variables individually had some value in predicting mortality, none of the variables by itself was both highly sensitive and highly specific for predicting mortality. Our data suggest multiple-trauma cases with 2 or more indicators of acidosis at admission have a guarded to poor prognosis (Figure 2), and aggressive therapy with close clinical monitoring to assure continued improvement should be instituted. Conversely, multiple-trauma cases with normal acid–base values at admission are much more likely to survive and have a good prognosis.

The only postresuscitation indicator of acidosis that was associated with survival in this analysis was lactate. The other variables were not correlated with lactate, and their correlations with each other were lower than those at the preresuscitation therapy time point. Therapeutic interventions such as the administration of sodium bicarbonate likely act to invalidate base excess, bicarbonate, and pH as indicators of the adequacy of resuscitation and patient prognosis. Similarly, but with an opposite effect, the administration of normal saline may cause hyperchloremic acidosis, also affecting postresuscitation base excess, bicarbonate, and pH but not lactate.24 For these reasons, lactate remains predictive of mortality after resuscitation, whereas the other parameters do not. The predictive value of lactate in the pre- and postresuscitation phases of treatment may be compared by referencing the top lines in Tables 4 and 7, respectively. The reliability of lactate as a valid indicator of acidosis and patient prognosis in the postresuscitation treatment period has high clinical relevance. When faced with discordant acid–base information, our study suggests that clinicians give more weight to lactate over the other parameters we measured.

The differences observed between the preresuscitation values of macaques that had follow-up data and those that did not suggest that animals with normal (or near-normal) values were considered low risk by the attending veterinarian and were not reassessed after initial therapy. For this reason, the estimated predictive values for the postresuscitation therapy variables may be biased. This bias may lead to underestimation (bias toward null hypothesis) of the predictive values of these variables in our study group.

This study demonstrates the utility of acid–base assessment of severe trauma cases on admission to ICU as well as the reliability of serial serum lactate measurements for patient evaluation during treatment and hospitalization. It is our hope that these results will assist clinicians in triage decisions by quickly differentiating animals at high risk for mortality. Early and aggressive resuscitation therapy results in improved chances of survival. Unfortunately, some animals will not respond to these therapeutic efforts, and their conditions will continue to deteriorate. The early recognition of patients unlikely to recover may assist clinicians in their difficult task of determining when humane euthanasia is appropriate, thereby reducing needless patient suffering and improving animal welfare. This information also may benefit future studies by providing valid outcome measures to objectively compare various treatments of traumatic shock in rhesus macaques.

The current study had several limitations. The predictive values as well as the sensitivity and specificity values presented in this study are dependent on the overall mortality rate. For this reason, these values may not be replicated in other institutions that may have different mortality rates or that may test a broader (or narrower) range of trauma cases.

One of the initial goals of our study was to establish cutoff values for the potential predictors of mortality we evaluated. The most reliable predictor of mortality in our study was serum lactate. However, we were unable to establish fixed cutoff values for mortality because of low numbers of subjects in the classes that our statistical model specified as most vulnerable (those with lactate values 3.0 to 4.0 postinitial fluid resuscitation). For this reason, expanded studies are warranted.

As stated previously, the acid–base parameters in the posttreatment analysis (analysis 2) were measured after aggressive resuscitation therapy and may have been affected by the therapeutic intervention. The number of subjects and timing of posttreatment measurements available for our retrospective study were insufficient to determine the magnitude and time interval of the effect of therapy on posttreatment variables. Our posttreatment results may not be generalizable to animals receiving other treatment modalities. An expansion of the study population and more frequent measurements during the posttreatment time period likely would clarify these points. In addition, a larger study would allow evaluation of other potential confounders.

Our desire is to create a consortium so that data from trauma cases at other National Primate Research Centers may be included in a similar future analysis. Initial efforts to capture nonhuman primate phenotypes from these facilities in a coordinated way are being undertaken with the formation of the National Primate Research Centers Phenotyping Working Group under the direction of the National Center for Research Resources in the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible with support from the Oregon National Primate Research Center core grant award P51RR000163-50 and the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute, grant number UL1 RR024140 from the National Center for Research Resources, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

References

- 1.Abramson D, Scalea TM, Hitchcock R, Trooskin SZ, Henry SM, Greenspan J. 1993. Lactate clearance and survival following injury. J Trauma 35:584–588, discussion 588–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aduen J, Bernstein WK, Miller J, Kerzner R, Bhatiani A, Davison L, Chernow B. 1995. Relationship between blood lactate concentrations and ionized calcium, glucose, and acid–base status in critically ill and noncritically ill patients. Crit Care Med 23:246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakker J, Coffernils M, Leon M, Gris P, Vincent JL. 1991. Blood lactate levels are superior to oxygen-derived variables in predicting outcome in human septic shock. Chest 99:956–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramanyan N, Havens PL, Hoffman GM. 1999. Unmeasured anions identified by the Fencl–Stewart method predict mortality better than base excess, anion gap, and lactate in patients in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 27:1577–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox DR. 1972. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion). J Royal Stat Soc B (Method). 34:187–220 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis JW, Kaups KL, Parks SN. 1998. Base deficit is superior to pH in evaluating clearance of acidosis after traumatic shock. J Trauma 44:114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Didwania A, Miller J, Kassel D, Jackson EV, Jr, Chernow B. 1997. Effect of intravenous lactated Ringer solution infusion on the circulating lactate concentration: part 3. Results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med 25:1851–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eachempati SR, Reed RL, 2nd, Barie PS. 2003. Serum bicarbonate concentration correlates with arterial base deficit in critically ill patients. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 4:193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Englehart MS, Schreiber MA. 2006. Measurement of acid–base resuscitation endpoints: lactate, base deficit, bicarbonate, or what? Curr Opin Crit Care 12:569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FitzSullivan E, Salim A, Demetriades D, Asensio J, Martin MJ. 2005. Serum bicarbonate may replace the arterial base deficit in the trauma intensive care unit. Am J Surg 190:961–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forni LG, McKinnon W, Lord GA, Treacher DF, Peron JM, Hilton PJ. 2005. Circulating anions usually associated with the Krebs cycle in patients with metabolic acidosis. Crit Care 9:R591–R595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husain FA, Martin MJ, Mullenix PS, Steele SR, Elliott DC. 2003. Serum lactate and base deficit as predictors of mortality and morbidity. Am J Surg 185:485–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James JH, Luchette FA, McCarter FD, Fischer JE. 1999. Lactate is an unreliable indicator of tissue hypoxia in injury or sepsis. Lancet 354:505–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan LJ, Kellum JA. 2008. Comparison of acid–base models for prediction of hospital mortality after trauma. Shock 29:662–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerl ME. 2005. Acid–base, oximetry, and blood gas emergencies. : Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. St Louis (MO): Elsevier Saunders [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavery RF, Livingston DH, Tortella BJ, Sambol JT, Slomovitz BM, Siegel JH. 2000. The utility of venous lactate to triage injured patients in the trauma center. J Am Coll Surg 190:656–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oestern HJ, Trentz O, Hempelmann G, Trentz OA, Sturm J. 1979. Cardiorespiratory and metabolic patterns in multiple-trauma patients. Resuscitation 7:169–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raum M, Rixen D, Linker R, Gregor S, Holzgraefe B, Neugebauer E. 2002. [Influence of lactate infusion solutions on the plasma lactate concentration] Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 37:356–358 [Article in German] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rixen D, Siegel JH. 2005. Bench-to-bedside review: oxygen debt and its metabolic correlates as quantifiers of the severity of hemorrhagic and posttraumatic shock. Crit Care 9:441–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutherford EJ, Morris JA, Jr, Reed GW, Hall KS. 1992. Base deficit stratifies mortality and determines therapy. J Trauma 33:417–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schapiro SJ, Bloomsmith MA, Suarez SA, Porter LM. 1996. Effects of social and inanimate enrichment on the behavior of yearling rhesus monkeys. Am J Primatol 40:247–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegel JH, Rivkind AI, Dalal S, Goodarzi S. 1990. Early physiologic predictors of injury severity and death in blunt multiple trauma. Arch Surg 125:498–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith I, Kumar P, Molloy S, Rhodes A, Newman PJ, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. 2001. Base excess and lactate as prognostic indicators for patients admitted to intensive care. Intensive Care Med 27:74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Todd SR, Malinoski D, Muller PJ, Schreiber MA. 2007. Lactated Ringer's is superior to normal saline in the resuscitation of uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma 62:636–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]