Abstract

Recent work has shown that ablation of p110β, but not p110α, markedly impairs tumorigenesis driven by loss of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in the mouse prostate. Other laboratories have reported complementary data in human prostate tumor lines, suggesting that p110β activation is necessary for tumorigenesis driven by PTEN loss. Given the multiple functions of PTEN, we wondered if p110β activation also is sufficient for tumorigenesis. Here, we report that transgenic expression of a constitutively activated p110β allele in the prostate drives prostate intraepithelial neoplasia formation. The resulting lesions are similar to, but are clearly distinct from, the ones arising from PTEN loss or Akt activation. Array analyses of transcription in multiple murine prostate tumor models featuring PI3K/AKT pathway activation allowed construction of a pathway signature that may be useful in predicting the prognosis of human prostate tumors.

The loss of the phosphatase and tensin homolog located on human chromosome number 10 (PTEN) is especially prominent in prostate cancer, with mutations found in more than 60% of advanced prostate cancers (1). In cells, PTEN plays its role as a tumor suppressor by dephosphorylating the 3′ position of the inositol head group of phosphatidylinositol 3, 4, 5 triphosphate (PIP3), a key lipid second messenger that activates the serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) kinase AKT and other downstream effectors to regulate multiple cellular functions, including proliferation, survival, migration, and tumorigenesis. PIP3 is generated by the activation of PI3Ks in response to the activation of a large number of growth factor receptors and oncogenes (2, 3). The frequent inactivation of PTEN in prostate cancer suggests the activation of the PI3K signaling pathway is intimately involved in the genesis of prostate tumors.

PI3Ks constitute a small family of lipid kinases that commonly is subdivided into three classes (I, II, and III) by substrate specificity and subunit composition. Of these classes, only the class I (IA and IB) enzymes have been implicated in cancer. In particular, class IA PI3Ks, which are activated by receptor tyrosine kinases, G protein-coupled receptors, and oncoproteins, consist of a p110 catalytic subunit (p110α, p110β, or p110δ) complexed to one of a family of regulatory subunits (p85α, p55α, p50α, p85β, or p55γ), collectively called “p85” (2, 3). Both p110α and p110β isoforms are expressed ubiquitously, whereas the p110δ subunit is found primarily in leukocytes (2, 3).

The p110α subunit has been well studied in cancer because of the frequent presence of activating mutations in p110α in common tumors, but p110β has received somewhat less attention. Because both isoforms share a common domain structure and interact with receptors via the same p85 subunits, the two enzymes long were thought to be functionally redundant. However, the fact that KO of either isoform is lethal at different early embryonic developmental stages suggested that they actually might be functionally distinct (4, 5). Although studies in chick embryo fibroblast cells (6) and human mammary epithelial cells in vitro (7) have shown that p110β can be rendered oncogenic, genetic alterations have not been found in human tumors (8), with the exception of gene amplification in ovarian cancer (9). The idea that p110β might have unique functions has been bolstered recently by studies using isoform-specific chemical inhibitors (10), conditional KO (11, 12), and kinase-dead knockin mice (13). These studies showed that p110β ablation, inactivation, or inhibition diminished signaling from a number of G protein-coupled receptors but had little effect of on PDGF, EGF, insulin-like growth factor, and insulin signaling in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. However, a study using p110β kinase-dead knockin mice demonstrated that p110β also couples to a subset of receptor tyrosine kinases (13–15).

Conventional KO of PTEN (16, 17) and tissue-specific deletion in the prostate (18–21) demonstrated that PTEN deletion induced aggressive prostate cancer. Although these genetic studies have demonstrated the importance of the PI3K pathway in prostate cancer, the roles of the individual isoforms of PI3Ks in the initiation or progression of prostate cancer driven by PTEN loss have remained largely unknown. However, a recent study with conditional KO mice has shown that KO of p110β largely blocks the initiation of tumors in the anterior prostate (AP), whereas ablation of p110α in the same model had no effect on prostate tumor formation (12).

Given the accumulating data suggesting that the two p110 isoforms of PI3K may perform fundamentally different roles in any given tissue, including the prostate, it seems important to examine each p110 isoform separately. Here, we have probed the ability of an activated allele of p110β to induce prostatic tumors. We find that prostate-specific expression of a p110β allele activated by myristoylation induces mouse prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (mPIN).

Results

Expression of an Activated p110β Transgene in the Mouse Prostate.

A constitutively activated form of p110β was created by fusing the myristoylation signal from pp60c-src, along with a FLAG epitope tag, to the N terminus of murine p110β, resulting in a chimeric gene, termed “MF-p110β,” which then was subcloned into an androgen-responsive cassette driven by the (ARR)2PB promoter (22) (Fig. S1A). Two transgenic (TG) mouse lines that showed germ line transmission of the transgene were selected and maintained for further studies. Expression of MF-p110β was detected in the ventral prostate (VP) and, to a lesser extent, in the dorsal/lateral prostate (DLP) of TG mice by immunoblotting experiments (Fig. S1B). Consistent with the observed expression levels, strong lipid kinase activity in the VP and weaker activity in the DLP were seen by in vitro lipid kinase assay (Fig. S1C). As shown in Fig. S1D, Serine473 of AKT [pAKT(Ser473)] showed significant phosphorylation in the VP of the TG mice. Taken together, these results confirmed that p110β is expressed appropriately and is functionally active in the TG mouse prostate.

Activation of p110β in the Mouse Prostate Leads to mPIN That Progresses with Age.

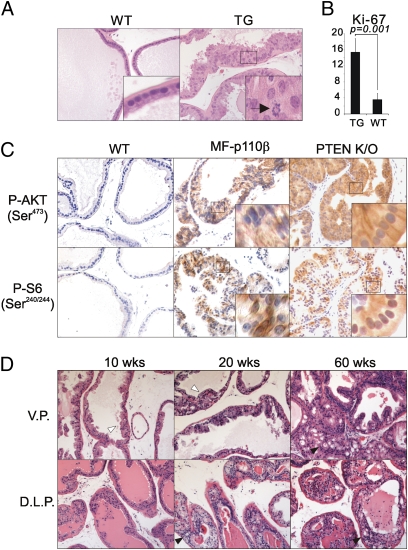

Because MF-p110β is expressed predominantly in the VP, we focused on this tissue to see if MF-p110β expression gave rise to any indication of mPIN. As shown in Fig. 1A, epithelial cells from the VP of TG mice showed focal stratification and nuclear atypia, including irregularly sized and elongated nuclei with prominent nucleoli, clear indications of mPIN. In addition, mitotic cells (Fig. 1A) and significantly higher numbers of Ki-67–positive cells were found in the VPs of TG mice than in WT littermates (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrated that expression of activated p110β induces mPIN.

Fig. 1.

The transgene MF-p110β induces mPIN, which progresses in severity with aging. (A) H&E staining of VPs of WT and TG 20-wk-old mice. The characteristics of mPIN are seen in the VP of a TG mouse, whereas normal prostatic architecture is seen in the VP of a WT mouse. Mitotic cells detected in the TG tissues are indicated with an arrow. (B) Elevated Ki-67–positive cells are evident in mPIN driven by MF-p110β. Ki-67–positive cells were counted from five microscopic fields and averaged. P value was calculated by t test. (C) IHCs of pAKT(Ser473) and pS6(Ser240/242) on VPs of WT and TG 19-wk-old and PTEN KO 8-wk-old mice. Note the darker staining and membrane localization of the phospho-Akt signal in the PTEN-null mice. (D) H&E staining of prostates isolated at 10, 20, and 60 wk of age. At least six mice were analyzed at each time point. White arrowheads indicate mPIN, and black arrowheads indicate cribriform structures. All images were taken at 40× magnification.

To examine if the activation of PI3K/AKT pathway can be detected in the MF-p110β–driven lesions, immunohistochemistry (IHC) experiments were conducted. Consistent with Fig. S1D, higher pAKT(Ser473) levels were detected in the lesions of TG mice (Fig. 1C). In addition, activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway was increased markedly, as judged by the level of phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (Ser240/244) [p-S6(Ser240/244)] by IHC (Fig. 1C). Notably, the intensity of pAKT(Ser473) in the MF-p110β TG mouse model is weaker than that seen in mice with prostatic deletion of PTEN, which show strong staining localized primarily to the membrane. This finding suggests that the amplitude of PI3K signaling represented by the levels of PIP3 and localization of AKT may differ between PTEN loss and activation of p110β. This observation also may explain the higher degree of mPIN development seen in the PTEN model. We also investigated whether the mPIN phenotype seen in MF-p110β mice progressed to more advanced lesions with age and whether prostate lobes other than the VP developed mPIN. The characteristics of mPIN were seen focally, exclusively in the VP at 10 wk (Fig. 1D). At 20 wk, mPIN involved a larger number of ducts in the VP, and more advanced types of abnormalities including cribriform structures were observed in the DLP lobes. Indeed, more than 50% of the ducts were characterized by a proliferation of epithelial cells with prominent nuclear atypia often forming cribriform structures in the DLP. At 60 wk, mPIN was more extensive in both the VP and DLP. These results indicate that mPIN progresses with age, especially in DLP lobes. The AP, where the transgene was expressed most poorly, never displayed clear mPIN. Although we did not see any invasiveness, the pattern of disease progression in our model is noteworthy for its similarity to human prostate cancers that gradually progress with age.

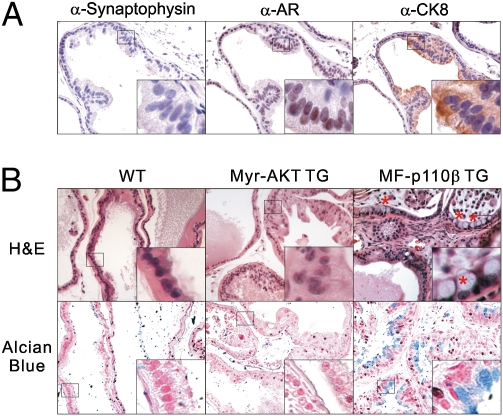

Prostatic Expression of the p110β Transgene Induces mPIN with Luminal Differentiation That Later Displays Mucinous Metaplasia.

Next, we tested whether the cancerous cells induced by the activated allele of p110β express luminal cell markers. A series of IHCs were performed using markers for different cell types. Cells filling the luminal space did not show any signal when we used a neuroendocrine marker (synaptophysin) (Fig. 2A). Instead, strong androgen receptor (AR) staining (a prostate epithelial cell marker) and CK8 (a luminal cell marker) signals were observed (Fig. 2A). This result indicates that, similar to human PIN, the mPIN induced by p110β expresses luminal cell markers. Interestingly, the p110β TG mice displayed morphologic characteristics consistent with mucinous metaplasia, documented by the presence of goblet cells that stain positive with Alcian blue (Fig. 2B). This phenotype was not seen in the AKT TG mice or PTEN KO mice but does occur in human prostate tumors at a low frequency. A similar phenotype has been reported in other prostate tumor mouse models driven by activated H-ras (23), expression of Fgf8b coupled with heterozygous loss of PTEN (24), or KO of p63 (25, 26).

Fig. 2.

The neoplastic cells in the prostate display the AR and CK-8 staining characteristic of luminal cells. (A) IHCs of synaptophysin, AR, and CK-8 of the VP in 10-wk-old mice. (B) Alcian blue staining of VP sections from WT, myr-AKT TG, and MF-p110β TG 60-wk-old mice. Positive cells are marked with red stars. Images were taken at 40× magnification.

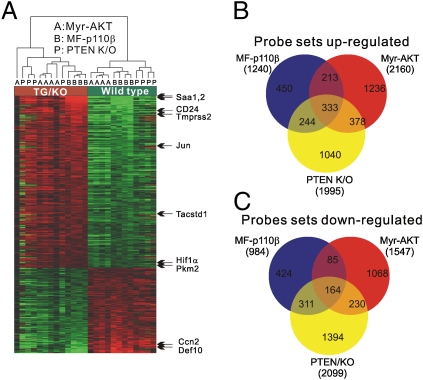

Comparison of Gene-Expression Profiles from Tumors Induced in MF-P110β, myr-AKT, and PTEN KO Mice.

To seek the molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic similarities and differences among mouse prostate cancer models featuring activation of the PI3K pathway, we collected microarray expression data from p110β TG mice, PTEN KO mice, and publicly available data for Akt TG mice (GSE1413) (27). We identified the differentially expressed genes independently for each of the three expression profiles and then identified the genes that were common to all three comparisons. A total of 497 probe sets were identified (Fig. 3A and Dataset S1), 333 of which were up-regulated (Fig. 3B) and 164 of which were down-regulated (Fig. 3C). These genes could be direct targets of the PI3K pathway or more generally associated with tumor development. Examples of up-regulated genes were SAA1, Tmprss2, PAK1, Pgk1, Hif1a, Tacstd1/2, CD24a, and Pkm2, whereas Nkx3.1 and Defn10 were down-regulated. Among the genes that were up-regulated, the one with the highest fold-change was SAA1, which has been described as a cancer marker in several tumor types (28). Up-regulation of Hif1α suggests that activation of the PI3K pathway could be associated with the hypoxia pathway, a possibility that is supported by further data given below. Expression of a number of genes, including Tff3, Klf4, multiple Klks, and Ccnd2, was regulated uniquely in the p110β mice among the three mouse models (Dataset S2). One of the most highly up-regulated genes unique to the MF-p110β TG mouse is Klf4. Notably, KO of Klf4 results in the loss of 90% of goblet cells in the colon (29), a cell type found in p110β TG tumors but not reported in Akt TG mice or in PTEN KO mice.

Fig. 3.

Transcription microarray analysis of three murine prostate cancer models driven by the activation of PI3K pathway. (A) Hierarchical clustering and heat map of differentially expressed genes identified by separate t tests for myr-Akt (designated “A”), MF-p110β (designated “B”), and PTEN KO (designated “P”) mice. Up-regulated genes are shown in red; down-regulated genes are shown in green. Genes of particular interest are indicated by arrows on the side of the heat map. (B and C) Venn diagrams represent the overlap of genes differentially expressed among the three mouse prostate cancer models, MF-p110β, myr-Akt, and PTEN KO. Up- (B) and down- (C) regulated genes are diagrammed separately.

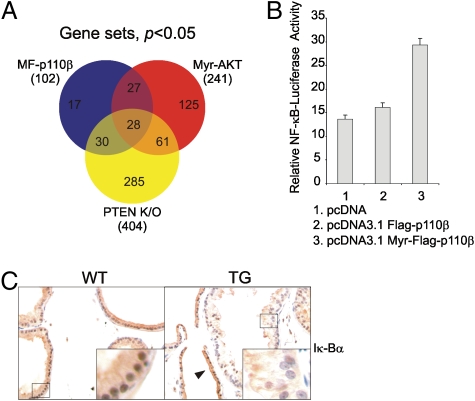

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis Identified a Common Activation of Metabolism, Hypoxia, Myc, and NF-κB Gene Sets Among Mouse Models.

To extract additional biological significance from the array results, we used gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to interrogate array data from MF-p110β TG, PTEN KO, and myr-Akt TG mice. As shown in Fig. 4A and Fig. S2, 28 enriched gene sets (P < 0.05) were identified consistently in all three models. Among these gene sets, those involved in metabolism and hypoxia previously had been identified in tumors resulting from activation of Akt (27, 30). Additional interesting gene sets that were found to be differentially regulated in all three models and that previously have been linked to human prostate cancer were those associated with the activation of myc (31) and NF-κB (32). Enriched gene sets found only in the p110β expression data were identified also. However, most of these gene sets also were seen in either Akt TG or PTEN KO mice, but with statistically lower confidence (Dataset S3). This information suggests that the basic landscape of target genes regulated in each of the models is similar, as might be expected because each model is driven by activation of the same signaling pathway. Of the commonly regulated gene sets, the NF-κB set is of particular interest because considerable evidence suggests functional interactions between the PI3K and NF-κB pathways. Previous studies reported that PI3K signaling positively regulated the activation of NF-κB via an AKT/IκB kinase axis (33, 34). Notably, a recent study has shown that an activated allele of Akt induced the activation of NF-κB in chicken embryonic fibroblasts (35). We next tested if our activated p110β allele could up-regulate NF-κB transcriptional activity in vitro. A luciferase reporter construct containing multiple NF-κB binding sites located up-stream of a minimal thymidine kinase (TK) promoter was cotransfected into the DU145 prostate cancer cell line along with constructs expressing WT or activated p110β. As shown in Fig. 4B, the constitutively active allele resulted in marked up-regulation of NF-κB–driven luciferase expression. Finally, we evaluated the status of IκB-α, an inhibitory protein of the NF-κB pathway, by IHC. As shown in Fig. 4C, the IκB-α signal was significantly lower in cells showing mPIN than in normal cells in the same gland or in the WT prostate, suggesting p110β-driven activation of the NF-κB pathway in these tumors.

Fig. 4.

GSEA identifies the NF-κB pathway as a target common to three mouse models featuring PI3K pathway activation. (A) Venn diagram represents the overlap of gene sets identified by GSEA. (B) NF-κB reporter assays show up-regulation of NF-κB activity with the expression of an active allele of p110β in vitro. An NF-κB reporter construct was cotransfected into DU145 cells with vector control, a FLAG epitope-tagged WT of p110β (FLAG-p110β), or an active allele of p110β (myr-FLAG p110β). (C) IHCs of IκBα on the VP of WT and TG mice. The black triangle denotes the higher IκB-α signal in normal cells than in cells showing mPIN in the same gland. The pictures were taken at 40× magnification.

Cross-Species Comparisons Between Human and Mouse Prostate Cancer.

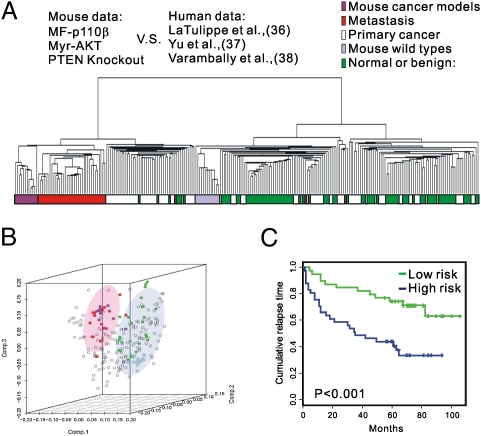

To study the relevance of molecular signatures from our mouse model to human prostate cancers, we compared the molecular signature associated with activation of the PI3K pathway in murine prostate tumors with publicly available datasets for human prostate tumors. We first tested to see if the molecular signature of murine prostate cancers driven by the activation of p110β was correlated with a particular stage of human prostate cancer. Three published studies have shown that molecular signatures segregated distinctly with human disease status, distinguishing normal or benign prostatic tissue from primary localized cancer and metastatic cancer (36–38). After human orthologs of mouse genes that were differentially expressed in the MF-p110β gene-expression profile were selected, all data sets of human and mouse expression profiles were normalized separately before datasets were integrated. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Fig. 5A) and principal component analysis (Fig. 5B) were used for comparisons. Notably, the profile of the mouse prostate tumors driven by activated p110β (as well as those for PTEN KO and Akt TG models) coclustered with the profile of metastatic human prostate cancer by either method. This clustering indicates that the molecular signatures of mouse prostate cancers driven by activated PI3K signaling are associated closely with more aggressive human prostate cancer, even though these mouse models did not develop metastatic phenotypes during our observational time frame.

Fig. 5.

Cross-species comparison of gene-expression profiles. (A and B) A mouse gene signature obtained from a MF-p110β TG mouse coclusters with metastatic human prostate cancer samples by unsupervised hierarchical clustering (A) and principal component analysis (B). (C) Kaplan–Meier analysis shows the PI3K signature has prognostic power to predict recurrent prostate cancers.

The relevance of the mouse gene-expression profiles to human prostate cancer was evaluated further using human prostate cancer data sets that were annotated with clinical outcomes (39). After identifying the human orthologs of the genes that consistently were expressed differentially among the three mouse models featuring PI3K activation and retaining only the genes with variance (>1) in expression in the human data (Fig. 3 B and C and Dataset S4), we applied hierarchical clustering across the entire set of human prostate samples. This approach led to the identification of two main subsets with significantly different prognosis. Kaplan–Meier analysis of the two main clusters segregated patient samples into two groups, high-risk and low-risk (Fig. 5C), with significantly different times to relapse (log-rank, P < 0.001). The high-risk group displayed poorer prognosis than the low-risk group (median times to relapse of 2.9 and 5.6 y, respectively) and, as expected, a higher 1-y recurrence rate (58.7% vs. 29.4%) from the time of diagnosis.

Discussion

Aberrant activation of the PI3K signaling cascade is found in many cancers arising via gain-of-function mutations in p110α or AKT or loss-of-function mutations in PTEN. The role of the PI3K pathway in prostate cancer has been modeled previously by activation of Akt and both conventional and conditional KO of PTEN. Mouse tumor models using activated alleles of p110α have been reported recently, although not in the prostate (40). Here, we describe such a model for p110β. The molecular features and pathology of the resultant prostate tumors are similar to those of human prostate cancers. Notably, the prostate tumors driven by MF-p110β featured distinct gene-expression profiles and phenotypes as compared with either prostatic deletion of PTEN or expression of activated Akt, suggesting that alternative routes to activation of the PI3K pathway may yield physiologically distinct outcomes.

To date, activating mutations in PI3K have been found in p110α but not in p110β. Although this disparity might arise simply because it is more difficult to activate p110β than p110α via point mutations, it still raises the question of the suitability of modeling prostate cancer with oncogenic p110β. Moreover, prostate cancers are associated primarily with the loss of PTEN, whereas PI3K mutations are observed only rarely. Thus, a key question centers on which p110 isoform(s) carries the tumorigenic signal in PTEN-null prostate cancer cells. A recent study conducted by our group sheds some light on this point. We studied mice in which PTEN and either p110α or p110β were ablated in the murine APs via Cre-mediated tissue-specific recombination (12). Compound mice with p110α and PTEN deletion in prostate still developed tumors comparable to those seen upon PTEN deletion alone. In contrast, compound mice with both p110β and PTEN ablated in their prostates showed minimal signs of tumor formation, suggesting that p110β may be the major player in prostate tumors with PTEN loss. Consistent with this result, recent RNAi-based knockdown studies have demonstrated that p110β, not p110α, is a key player in AR activation in prostate cancer (41) and that the PTEN-deficient cell lines tested depend on p110β rather than p110α (42). In the present work, we have demonstrated that activated p110β does indeed induce mPIN in murine models, although no clear invasions are detected. It will be interesting to see if activation of p110α also generates tumors in the mouse prostate.

Including the present study, three murine models featuring the activation of the PI3K pathway in the prostate are available for comparison: prostatic deletion of PTEN, prostatic expression of myr-Akt, and prostatic expression of MF-p110β. There are clear similarities among these models; notably, GSEA suggests that similar pathways are involved, including those affecting metabolism, hypoxia, and NF-κB activation. Activation of NF-κB by the PI3K pathway has been debated. The data we show here are consistent with some previous publications but are contrary to other studies (33–35, 43). Although the three models showed the similarities, each develops phenotypically distinct lesions. PTEN-null mice display the most aggressive lesions that progress from hyperplasia to either invasiveness (18–21) or metastasis (20), whereas activation of Akt induces mPIN confined to the VP. In contrast, neoplasia in our MF-p110β model is manifest first as mPIN and gradually progresses to develop more advanced abnormalities characterized by nuclear atypia and cribriform structures with involvement of both the VP and DLP as the animals age. Last, a mucinous metaplastic phenotype was detected only in the MF-p110β animals.

Several explanations may account for these differences. The simplest is that the virulence of the tumor may be a direct result of the point in the pathway in which the driving mutation lies. Thus Akt lying farthest downstream would yield the least aggressive tumors. Differences between PTEN and p110β lesions are more difficult to parse in this manner. Perhaps advanced tumor formation of the PTEN tumors arises from PTEN's roles outside the PI3K pathway. For instance, PTEN is known to regulate genomic stability (44); thus PTEN-null tumors might invade because of their more rapid accumulation of secondary mutations. It also is possible that the concentration of PIP3 generated by PTEN loss and the p110β transgene are significantly different. Perhaps, if PIP3 concentrations are over a certain threshold level, signals might propagate in more multifarious directions via a subset of the ∼300 pleckstrin homology domain-containing proteins (45). The PTEN literature suggests that PTEN expression levels are inversely correlated with the severity of prostate cancers in mice (19). In human tumors, the loss of a single PTEN allele is detected frequently in primary prostate cancer, whereas biallelic deletion of PTEN is seen more often in the advanced prostate cancers, including metastasis (46).

The most characteristic phenotype of MF-p110β mice is mucinous metaplasia marked by the appearance of cells resembling goblet cells. Notably, expression of goblet cell markers, such as Tff3 and Klf4 (both up-regulated), is altered in MF-p110β TG mice but not in Akt TG mice or PTEN-null mice. This metaplasia occurs relatively rarely in human prostate cancers, and to date few if any tumors of this phenotype have undergone systematic sequence analysis. Hence the possibility exists that this tumor subtype might feature activation of p110β. Notably, Tff3 is one of the most highly expressed genes in advanced human prostate cancers (47, 48). Therefore, it would be interesting to reevaluate the status of Klf4 and p110β expression in prostate cancers showing high expression levels of Tff3. It is, however, somewhat mysterious why PTEN tumors, which appear to use p110β preferentially in signaling, do not show a similar phenotype. Perhaps p110β overexpression has additional effects beyond its lipid kinase activity. Indeed, the fact that p110β kinase-dead knockin mice can reach adulthood (13), whereas loss of p110β is lethal in embryos (5), suggests that p110β may have kinase-independent functions. Thus, the transdifferentiation observed in MF-p110β mice might be occasioned via reprogramming in the mouse prostate by a kinase-independent function of p110β. Alternatively, adding a myristoylation signal to p110β protein could affect its function through an alteration of its subcellular localization. A recent study reported a novel nuclear function of p110β in DNA replication (49). The construct used here may retain only functions initiated in proximity to the lipid bilayer, and even these functions may be changed by potential changes in the particular membrane locations involved.

Few cross-species comparisons of array data in prostate cancers have been performed, in part because of the lack of sufficient expression data from both prostate animal models and clinically annotated human prostate tumor data. The first study of this type was carried out in myc-driven prostate cancer models and showed genes affected by myc status consistently appeared in both human and mouse cancers (50). We have attempted to extend such analyses to understand the nature of prostate cancers arising because of the activation of PI3K pathways. When we tried to map the transcriptional signature of our model to either primary or metastatic prostate cancers in humans, the gene sets from the MF-p110β mice coclustered with the orthologous human gene sets from metastatic cancers, even though in the TG mice these lesions do not invade or metastasize. Further statistical analyses suggested that the correlation is strong enough that it should not be ignored. How then might we reconcile the data? Recent data suggest that genes that help drive metastasis may be expressed already in primary cancers (51, 52). Thus, it is possible that MF-p110β could drive the expression of many genes required for metastasis but fail in activating other key genes. Alternatively, activation of p110β may be required for survival in a new microenvironment but may not be sufficient to drive invasion or metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Transgenic Mice.

The fragment myr-FLAG-p110β was generated by PCR and subcloned into the (ARR)2PB-cassette. The TG mice were generated at the Dana-Farber Transgenic Mice Core Facility. All procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Immunohistochemistry.

IHCs were carried out as previously described (12).

Gene-Expression Profiling.

Total RNAs were purified from VP and analyzed using MOE430A 2.0 chips (Affymatrix). The resulting data were analyzed using the R/Bioconductor software package.

Detailed information on the generation of TG mice, IHCs, Alcian blue staining, luciferase assays, and analyses of gene expression data, are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. S. Lee (University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston) for helpful discussions, Dr. A. Upadhyaya (University of South Florida, Tampa, FL) for helpful comments on the manuscript, Dr. W. Sellers (Novartis Phamaceuticals, Cambridge, MA) for the Akt TG mouse, Dr. R. Shivadasani (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) for reviewing slides, and Dr. E. Li (Novartis Pharmaceuticals) and J. Horner (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston) for creating the TG mice. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (including Grant P01CA089021 to T.M.R., L.C.C., and M.L.), the Prostate Cancer Foundation (to M.L.), the Linda and Arthur Gelb Center for Translational Research (to M.L.), and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Prostate Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (to T.M.R., L.C.C., and M.L.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: T.M.R. and M.L. are consultants for Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Data deposition: The microarray data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE21543).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1005642107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Suzuki H, et al. Interfocal heterogeneity of PTEN/MMAC1 gene alterations in multiple metastatic prostate cancer tissues. Cancer Res. 1998;58:204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanhaesebroeck B, Guillermet-Guibert J, Graupera M, Bilanges B. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:329–341. doi: 10.1038/nrm2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi L, Okabe I, Bernard DJ, Wynshaw-Boris A, Nussbaum RL. Proliferative defect and embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a deletion in the p110alpha subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10963–10968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi L, Okabe I, Bernard DJ, Nussbaum RL. Early embryonic lethality in mice deficient in the p110beta catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase. Mamm Genome. 2002;13:169–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02684023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denley A, Kang S, Karst U, Vogt PK. Oncogenic signaling of class I PI3K isoforms. Oncogene. 2008;27:2561–2574. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao JJ, et al. The oncogenic properties of mutant p110alpha and p110beta phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in human mammary epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18443–18448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508988102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samuels Y, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brugge J, Hung MC, Mills GB. A new mutational AKTivation in the PI3K pathway. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight ZA, et al. A pharmacological map of the PI3-K family defines a role for p110alpha in insulin signaling. Cell. 2006;125:733–747. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guillermet-Guibert J, et al. The p110beta isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signals downstream of G protein-coupled receptors and is functionally redundant with p110gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8292–8297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707761105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia S, et al. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008;454:776–779. doi: 10.1038/nature07091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciraolo E, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110beta activity: Key role in metabolism and mammary gland cancer but not development. Sci Signal. 2008;1:ra3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1161577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciraolo E, et al. Essential role of the p110beta subunit of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase in male fertility. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:704–711. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canobbio I, et al. Genetic evidence for a predominant role of PI3Kbeta catalytic activity in ITAM- and integrin-mediated signaling in platelets. Blood. 2009;114:2193–2196. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang SI, Parsons R, Ittmann M. Homozygous deletion of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in a subset of prostate adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:811–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Cristofano A, Pesce B, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat Genet. 1998;19:348–355. doi: 10.1038/1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma X, et al. Targeted biallelic inactivation of Pten in the mouse prostate leads to prostate cancer accompanied by increased epithelial cell proliferation but not by reduced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5730–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trotman LC, et al. Pten dose dictates cancer progression in the prostate. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratnacaram CK, et al. Temporally controlled ablation of PTEN in adult mouse prostate epithelium generates a model of invasive prostatic adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2521–2526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712021105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Thomas TZ, Kasper S, Matusik RJ. A small composite probasin promoter confers high levels of prostate-specific gene expression through regulation by androgens and glucocorticoids in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4698–4710. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scherl A, Li JF, Cardiff RD, Schreiber-Agus N. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intestinal metaplasia in prostates of probasin-RAS transgenic mice. Prostate. 2004;59:448–459. doi: 10.1002/pros.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong C, Saribekyan G, Liao CP, Cohen MB, Roy-Burman P. Cooperation between FGF8b overexpression and PTEN deficiency in prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2188–2194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurita T, Medina RT, Mills AA, Cunha GR. Role of p63 and basal cells in the prostate. Development. 2004;131:4955–4964. doi: 10.1242/dev.01384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Signoretti S, et al. p63 regulates commitment to the prostate cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11355–11360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500165102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majumder PK, et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada T. Serum amyloid A (SAA): A concise review of biology, assay methods and clinical usefulness. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:381–388. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz JP, et al. The zinc-finger transcription factor Klf4 is required for terminal differentiation of goblet cells in the colon. Development. 2002;129:2619–2628. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majumder PK, et al. Prostate intraepithelial neoplasia induced by prostate restricted Akt activation:Tthe MPAKT model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7841–7846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232229100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lapointe J, et al. Genomic profiling reveals alternative genetic pathways of prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8504–8510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sweeney C, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB is constitutively activated in prostate cancer in vitro and is overexpressed in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5501–5507. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0571-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozes ON, et al. NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romashkova JA, Makarov SS. NF-kappaB is a target of AKT in anti-apoptotic PDGF signalling. Nature. 1999;401:86–90. doi: 10.1038/43474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai D, Ueno L, Vogt PK. Akt-mediated regulation of NFkappaB and the essentialness of NFkappaB for the oncogenicity of PI3K and Akt. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2863–2870. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LaTulippe E, et al. Comprehensive gene expression analysis of prostate cancer reveals distinct transcriptional programs associated with metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4499–4506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu YP, et al. Gene expression alterations in prostate cancer predicting tumor aggression and preceding development of malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2790–2799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varambally S, et al. Integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of prostate cancer reveals signatures of metastatic progression. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glinsky GV, Glinskii AB, Stephenson AJ, Hoffman RM, Gerald WL. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:913–923. doi: 10.1172/JCI20032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engelman JA, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu Q, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase p85alpha and p110beta are essential for androgen receptor transactivation and tumor progression in prostate cancers. Oncogene. 2008;27:4569–4579. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wee S, et al. PTEN-deficient cancers depend on PIK3CB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13057–13062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802655105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delhase M, Li N, Karin M. Kinase regulation in inflammatory response. Nature. 2000;406:367–368. doi: 10.1038/35019154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen WH, et al. Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell. 2007;128:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemmon MA. Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrm2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carver BS, Pandolfi PP. Mouse modeling in oncologic preclinical and translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5305–5311. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garraway IP, Seligson D, Said J, Horvath S, Reiter RE. Trefoil factor 3 is overexpressed in human prostate cancer. Prostate. 2004;61:209–214. doi: 10.1002/pros.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vestergaard EM, Borre M, Poulsen SS, Nexø E, Tørring N. Plasma levels of trefoil factors are increased in patients with advanced prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:807–812. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marqués M, et al. Specific function of phosphoinositide 3-kinase beta in the control of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7525–7530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ellwood-Yen K, et al. Myc-driven murine prostate cancer shares molecular features with human prostate tumors. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:223–238. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramaswamy S, Ross KN, Lander ES, Golub TR. A molecular signature of metastasis in primary solid tumors. Nat Genet. 2003;33:49–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van ’t Veer LJ, et al. Expression profiling predicts outcome in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:57–58. doi: 10.1186/bcr562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.