Abstract

7-Aminomethyl-7-deazaguanine (preQ1) sensitive mRNA domains belong to the smallest riboswitches known to date. Although recent efforts have revealed the three-dimensional architecture of the ligand–aptamer complex less is known about the molecular details of the ligand-induced response mechanism that modulates gene expression. We present an in vitro investigation on the ligand-induced folding process of the preQ1 responsive RNA element from Fusobacterium nucleatum using biophysical methods, including fluorescence and NMR spectroscopy of site-specifically labeled riboswitch variants. We provide evidence that the full-length riboswitch domain adopts two different coexisting stem-loop structures in the expression platform. Upon addition of preQ1, the equilibrium of the competing hairpins is significantly shifted. This system therefore, represents a finely tunable antiterminator/terminator interplay that impacts the in vivo cellular response mechanism. A model is presented how a riboswitch that provides no obvious overlap between aptamer and terminator stem-loop solves this communication problem by involving bistable sequence determinants.

Keywords: RNA, chemical synthesis, labeling, bistable structures, riboswitches

Noncoding regions of mRNA that bind metabolites with high selectivity and specificity function as so-called riboswitches (1–3). They represent gene regulation systems that are widespread among bacteria and importantly, they do not rely on the assistance of proteins (4). Riboswitches consist of a metabolite-sensitive aptamer and an adjoining expression platform (5) Although impressive progress has been made in revealing three-dimensional structures of metabolite-bound aptamer complexes of various riboswitch classes (6), less is known about how binding of the metabolite to the aptamer is communicated into a structural change of the expression platform, which in turn signals “on” or “off” for gene expression. The simplified picture of bacterial transcription control is that upon metabolite binding either a mRNA terminator structure is formed, which causes the RNA polymerase to stop synthesis (off regulation) or an existing terminator is disrupted, which enables the polymerase to continue synthesis with the mRNA template (on regulation) (5, 7). In the case of translational control, accessibility versus sequestration of the Shine–Dalgarno sequence upon metabolite binding is the essence of the response mechanism for on versus off regulation, corresponding to hindrance or enabling of bacterial ribosome translation initiation (5, 7–9).

The preQ1 class I riboswitch is the smallest riboswitch known to date (10). Its aptamer comprises a stretch of only 34 nucleotides in the 5′ untranslated leader region of the respective messenger RNA and specifically recognizes 7-aminomethyl-7-deazaguanine (preQ1), which is an intermediate in queuosine biosynthesis (11). The minimal sequence and structure consensus refer to a hairpin comprising a five base-pair stem (P1) and a loop of eleven to thirteen nucleotides (L1) together with a 3′ single-stranded nucleoside overhang as originally proposed by Breaker and coworkers (10). In a previous study involving systematically mutated preQ1 aptamers in combination with chemical and NMR spectroscopic structure probing, we revealed that preQ1 binds with concurrent pseudoknot formation of the aptamer (12). At the same time, high-resolution structures of the aptamer–ligand complex were reported by three other groups and disclosed the molecular details of its three-dimensional architecture (13–15).

The question remains how nature uses the same aptamer domain to modulate the expression platform in different ways in various organisms. The key for understanding lies in the aptamer’s downstream sequence and the sequence overlap between aptamer and expression platform. Sequence conservation of the expression platform is significantly less compared to sequence conservation of the aptamer. Therefore, it becomes a complex task to reveal general rules for the molecular response mechanism of riboswitches. Our understanding will significantly grow if the ligand-induced folding process is dissected at the base-pair level in solution by including appropriate high-resolution methods such as NMR spectroscopy (16, 17).

In the present study, we have explored the ligand-induced folding process of the preQ1 sensing riboswitch from Fusobacterium nucleatum mRNA (Fig. 1) and revealed the sequence determinants and the folding kinetics leading to this organism’s response mode. For the expression platform, we have identified two competing stem-loop structures whose populations are significantly shifted upon formation of the ligand–aptamer complex. Thereby, the bistable character of the expression platform acts as a finely tunable antiterminator/terminator system for transcriptional control.

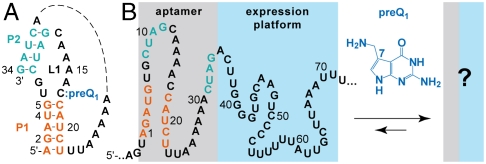

Fig. 1.

Riboswitches have to communicate binding of the aptamer and the ligand to the expression platform. (A) Recent studies have revealed the structure of the preQ1 riboswitch aptamer–ligand complex from Bacillus subtilis (13–15); however, the response mechanism remains undetermined at the molecular and biophysical level (B). Riboswitch sequence from Fusobacterium nucleatum investigated in this study.

Results and Discussion

We started our studies with structural probing using lead(II)-acetate on a 61 nt preQ1 riboswitch domain in the absence and presence of preQ1 (Fig. 2A). By doing so, we obtained a first hint for a distinct structural rearrangement in the expression platform as deduced from a cleavage band at C45/A46 that was observed only for the ligand-bound RNA. Likewise, enzymatic probing using S1 and V1 nucleases showed clearly different cleavage patterns for the expression platform of ligand-bound versus unbound riboswitch forms (G34–G40) (Fig. S1). Base pairing analysis of this particular sequence stretch revealed a potentially bistable stem-loop segment within the expression platform (Fig. 2B). We therefore synthesized the respective short segment of 21 nucleotides (G34–U54) and analyzed this RNA by comparative imino proton 1H NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 2C, Left) (18–20). Unequivocally, bistability was clearly reflected by two sets of signals assigned to two stem-loop structures in a ratio of 60∶40 (Fig. 2C, Right). Based on this evidence, the key question was how these two competing hairpins were responding to preQ1 in a full-length riboswitch construct. Initial attempts to segmentally label the expression platform with 15N/13C nucleotides by a combined approach using enzymatic transcription (T7 RNA polymerase) and enzymatic ligation (21, 22) to the chemically synthesized aptamer domain failed.

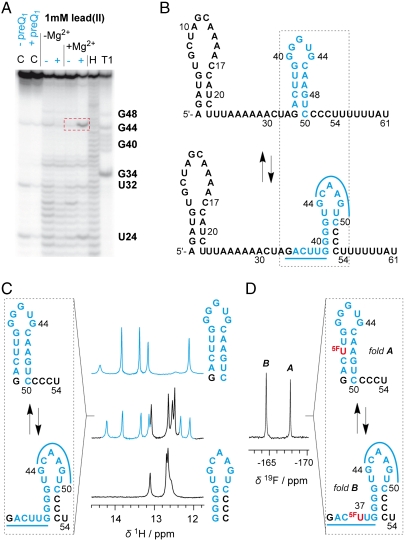

Fig. 2.

Secondary structure model for the 61 nt riboswitch construct in the absence of preQ1. (A) Probing for mapping a structural rearrangement in the expression platform in vitro by lead(II)-acetate in the absence (-) and presence (+) of a 4-fold excess of preQ1. C designates control reactions without and with preQ1. T1 and H designate RNase T1 and alkaline ladders, respectively. A specific and prominent Pb2+ cleavage site is evident between C45 and A46 (indicated by a red rectangle in dashed line). Conditions: cRNA = 2.5 μM; cpreQ1 = 12.5 μM; buffer: 50 mM KMOPS, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM Mg2+, pH 7.0, 298 K; lead(II)-acetate: 1 mM. (B) Bistable secondary structure model for the riboswitch in the absence of preQ1. (C) Evidence for a bistable segment (21 nt RNA) in the expression platform by comparative imino proton 1H NMR spectra. (D) Same bistable segment [as in (C)] labeled with noninvasive 5-F uridine and verification of 45∶55 equilibrium between fold A and B by 19F NMR spectroscopy [assignment based on short reference sequences as in (C)]. Conditions: cRNA = 0.5 mM, 25 mM sodium arsenate buffer, H2O/D2O = 9/1, pH 6.5, 298 K.

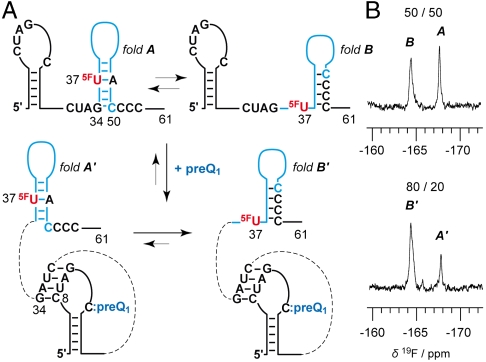

Alternatively, we decided to employ a 19F NMR spectroscopic approach (23–26) for the purpose to analyze how the equilibrium structures respond to preQ1 recognition. Because uridine at position 37 is ideally positioned in the sense that this pyrimidine is base-paired within one of the two proposed secondary structures while being unpaired in the alternative, we anticipated a straightforward assignment and quantification of the equilibrium structures using the noninvasive 5-fluoro pyrimidine label (Fig. 3A). This turned out to be the case: the 5-F uridine labeled 61 nt RNA construct clearly revealed a 50∶50 equilibrium of the hairpins in the expression platform of the ligand-unbound riboswitch, according to integration of the signals at -164.4 and -167.7 ppm (Fig. 3B, Upper; see also Fig. 2D: 5F-U labeled 21 nt RNA reference). Upon addition of two equivalents of preQ1, the equilibrium was clearly shifted in favor of the downstream situated G/C rich hairpin (80∶20; Fig. 3B, Lower). The binding of the full-length riboswitch to preQ1 was qualitatively verified by the imino proton spectra as well. The responsiveness of the expression platform, however, cannot be assessed in the unassigned signal crowd (Fig. S2) and demonstrates the convenience of the fluorine labeling approach used here.

Fig. 3.

PreQ1 riboswitch response. (A) Secondary structure model. (B) Verification of the equilibrium shift from equally populated, competing hairpins in the expression platform (fold A: fold B = 50∶50) toward dominant formation of the downstream hairpin (fold A′: fold B′ = 20∶80) upon ligand binding by 19F NMR spectroscopy. Conditions: cRNA = 0.2 mM, cpreQ1 = 25 mM, 25 mM sodium arsenate buffer, H2O/D2O = 9/1, pH 6.5, 298 K.

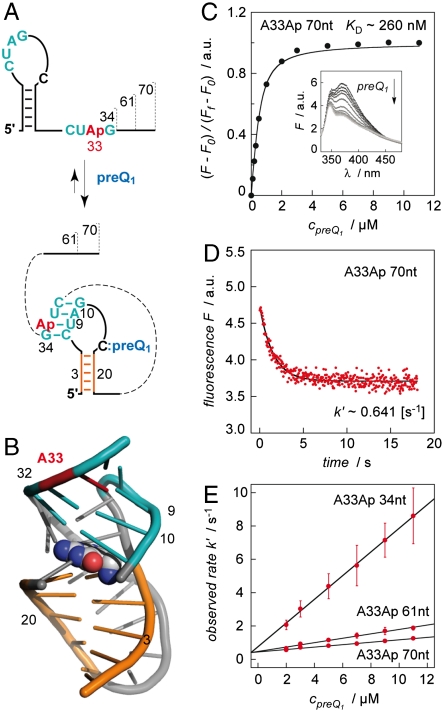

Encouraged by the NMR evidence for the proposed secondary structure rearrangement in the expression platform, we moved forward to determine the preQ1 riboswitch thermodynamics and kinetics of ligand binding under concurrent pseudoknot formation, studied according to a structure-based fluorescence spectroscopic approach introduced previously by our group (27–29). First, we synthesized an aptamer variant containing the fluorescent nucleobase analogue 2-aminopurine (Ap) instead of adenine at position 33 of the single-stranded 3′-overhang (A33Ap variant, Fig. 4A). Upon ligand binding, this nucleotide region is involved in Watson–Crick base pairing due to pseudoknot formation. Thereby, increased stacking interactions of Ap were expected (Fig. 4B) and are reflected in a pronounced fluorescence decrease (Fig. 4D). Ligand binding of the Ap variant was also confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Fig. S3). The fluorescence response upon ligand addition was used to determine an apparent KD value of 283 ± 55 nM (Fig. 4C, Table 1) and a rate constant of 60.2 ± 10.4 × 104 M-1s-1 under pseudo-first-order conditions (Fig. 4E, Table 1). The fluorescence traces to determine the observed rate values k′ were best fit to a monoexponential function (Fig. S4) and this supports the assumption that we monitor the transition from the free aptamer directly to the aptamer–ligand complex (pseudoknot formation). We mention that we applied RNA concentrations as low as 0.5 μM and a temperature of 25 °C for these experiments to keep potential kissing-loop dimer formation to a minimum (for details see gel shift analysis and probing experiments in SI Text, and Fig. S5). To evaluate thermodynamics and kinetics of the ligand-induced folding of the full-length riboswitch, we synthesized a A33Ap modified 61 nt variant. This RNA revealed a KD value of 208 ± 10 nM, which was comparable to the 34 nt aptamer domain (Table 1). However, the difference compared to the aptamer was a 4-fold smaller rate constant for the ligand-induced folding process (12.6 ± 0.97 × 104 M-1s-1; pseudo-first-order conditions) (Fig. 4E and Fig. S6). We verified the tendency of a slower response for increasing riboswitch length by an additional A33Ap modified construct that was extended by 9 nt at the 3′-end (70 nt construct) and obtained a further 2-fold decrease for the response (7.62 ± 0.29 × 104 M-1s-1; pseudo-first-order conditions) (Fig. 4E and Fig. S7).

Fig. 4.

Kinetic assessment of ligand-induced preQ1 riboswitch folding. (A) Schematics of secondary structure rearrangement of A33Ap labeled variants (34 nt, 61 nt, 70 nt). (B) Location of A33Ap (red) in the aptamer/preQ1 complex (coordinates based on the crystal structure from Ferre d’Amaré and coworkers of a homologous preQ1 aptamer from B. subtilis (13); representation of RNA in cartoon and of ligand (preQ1) in spheres. (C) Determination of apparent KD value. Fluorescence changes upon titration of A33Ap 70 nt labeled variant with preQ1. Normalized Ap fluorescence intensity plotted as a function of preQ1 concentrations. Changes in fluorescence (F-F0) were normalized to the maximum fluorescence measured in the absence of preQ1. The graph shows the best fit to a single-site binding model (SI Text). The inset shows fluorescence emission spectra (λex = 308 nm) from 330–480 nm for each preQ1 concentration; cRNA = 0.5 μM, 50 mM KMOPS, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0, at 298 K. (D) Representative fluorescence response of the A33Ap 70 nt variant upon preQ1 addition; conditions: same as (C) and cpreQ1 = 2.0 μM; mixing was performed with a stopped-flow apparatus. (E) Plot of observed rate k′ versus ligand concentration for the three different A33Ap variants as indicated. Observed rates were determined under pseudo-first-order conditions from three independent stopped-flow measurements. The slope of the plot yields the rate constant k (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Apparent binding constants KD and rate constants k of preQ1 riboswitch variants from Fusobacterium nucleatum

| Riboswitch variant |

[nM]* [nM]*

|

k298 K [M-1s-1]* |

| A33Ap 34 nt | 283 ± 55 | 60.2 ± 10.4 × 104 |

| A33Ap 61 nt | 208 ± 10 | 12.6 ± 0.97 × 104 |

| A33Ap 70 nt | 261 ± 23 | 7.62 ± 0.29 × 104 |

*Values are arithmetic means, determined from three independent experiments.

Moreover, we considered that steady-state kinetics of the ligand-induced hairpin rearrangement in the expression platform were accessible by a differently labeled Ap variant (Fig. 5). For the 61 nt A46Ap RNA, this secondary structure change should be accompanied by a fluorescence increase because the Ap nucleoside is stacked in the double helix of one hairpin (fold A) while it moves to the single-stranded loop region of the alternative (fold B′), which becomes higher populated in the preQ1 bound state (Fig. 5A). Fig. 5B shows an overlay between the 61 nt A33Ap variant with the Ap label close to the preQ1 binding site and the 61 nt A46Ap variant with the label at the site of secondary structure rearrangement of the expression platform. Both observed rates k′ are in the same order, however, it is noteworthy that the rearrangement in the expression platform proceeds with a 2-fold higher k′ once it is triggered by preQ1 recognition and concurrent pseudoknot formation.

Fig. 5.

Kinetic assessment of the ligand-induced stem-loop rearrangement in the expression platform. (A) Secondary structure model for the A46Ap labeled 61 nt variant; Ap becomes unstacked. (B) Representative fluorescence response (increase, red) upon preQ1 addition and comparison with the corresponding fluorescence response from the A33Ap 61 nt variant (decrease, orange; see also Fig. 4 and Table 1); k′ values as indicated. Conditions: cRNA = 0.5 μM, cpreQ1 = 2.0 μM, 50 mM KMOPS, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0, 298 K; mixing was performed with a stopped-flow apparatus.

With the above set of experiments we obtained unprecedented, base-pair resolved insight into the structural rearrangements occuring in the expression platform of a preQ1 riboswitch. Interestingly, there is no sequence overlap between the minimal aptamer sequence (A1–G34) and the actual terminator stem-loop structure (G39–C53) with the typical successive U-rich sequence (U54–U61). This “noncommunicative” situation has been resolved in this riboswitch by introducing an additional stem-loop structure, which importantly, on the one hand is in equilibrium with the terminator stem-loop (bistability) and on the other hand, adjoins to the aptamer with a single shared nucleotide (G34). As soon as the ligand preQ1 becomes present in sufficient concentration, formation of the aptamer/preQ1 complex causes destabilization of this antiterminator hairpin (G34–C50) and significantly shifts the equilibrium toward the downstream terminator stem-loop structure (G39–C53) (Fig. 5). Strikingly, antiterminator destabilization is founded on the minimal motif of a single competing base pair (G34:C50 versus G34:C8) that makes the riboswitch responsive. To some extent, this construction is reminiscent of the anti-antiterminator interactions exemplified by the SAM I riboswitch, where the aptamer does not overlap the terminator but rather other (albeit much larger) structures that control terminator formation (30).

Our data unequivocally shows that the preQ1 full-length riboswitch domain of F. nucleatum remains responsive to the ligand without restrictions. This is in contrast to other transcriptionally operating riboswitches whose full-length domains, in vitro, are usually incapable of ligand binding (Table S1). So far, this has been investigated and observed for purine riboswitches from Bacillus subtilis (27, 31, 32). For these systems, evidence has been collected that once the terminator stem-loop has formed it is thermodynamically too stable to allow refolding into a ligand-binding competent structure. Comparably, the FMN riboswitch forms an antiterminator structure that is incapable of ligand binding by involving almost the complete full-length domain (33). Therefore, based on the inherent sequence properties of these riboswitches, they must act under kinetic control in vivo otherwise they would be nonresponsive.

The preQ1 full-length riboswitch domain of F. nucleatum and its dedicated ligand reach thermodynamic equilibrium rapidly in vitro. The on-rate of this riboswitch is by far the fastest when compared with on-rates of the thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) (28), adenine (27, 32), guanine (34), or cyclic diguanylate riboswitch (35, 36) classes (Table S1). In particular, aptamer–ligand complex formation provides an on-rate, which translates to a time constant τ (the time required for e-1 of the reaction to go toward completion) of < 1 s (Fig. 4). With respect to active transcription of this preQ1 riboswitch a ligand-binding competent window can be defined by progressive attachment of nucleotides from position 35–54. This interval spans from the point at which the aptamer can form, to the point at which the terminator can form and would last about a second if the polymerase incorporated approximately 15 nucleotides per second (37, 38). The cellular concentration of preQ1 in this and other organisms is not reported in the literature; however, a concentration comparable to that of purines such as adenine (30 μM) (39) would be high enough to enable entire binding within the second time window. In other words, ligand/aptamer pseudoknot formation (occupying G34) is so fast that the complete antiterminator state cannot form and the sequential folding process directly runs into the terminator fold (“kinetic pathway” in Fig. 6). Furthermore, a ligand concentration of 30 μM would be much higher than the respective KD value and therefore also speaks up for kinetic control in vivo (33, 32).

Fig. 6.

Proposed model for the ligand-dependent antiterminator/terminator interplay in vivo (for discussion, see main text).

The intrinsic sequence properties of the preQ1 riboswitch would in principle allow thermodynamic control, however, this remains highly speculative and if so, would require pausing of the polymerase (40) at the U-rich strand region around the positions 54–70 (Fig. 6). Moreover, lower cellular ligand concentrations were required to slow down aptamer/preQ1 binding relative to formation of the antiterminator stem-loop, which is then followed by the ligand-induced structural shift toward the terminator stem-loop. The latter event occurs with an observed rate of about 2 s-1 (Fig. 5) and pausing of the polymerase must therefore last longer than half a second so that the polymerase is able to sense the shift toward the terminator stem-loop. In such a scenario, the riboswitch response mode were set to thermodynamic control (“thermodynamic pathway” in Fig. 6).

In summary, this study has revealed the bistable character and the ligand-induced rearrangement in the expression platform of a transcriptionally acting riboswitch with unprecedented structural resolution and in quantitative manner. By obtaining a comprehensive picture of the thermodynamics and kinetics of the folding process, our investigation contributes to a deeper understanding of riboswitch response mechanisms in general.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of RNA.

All oligoribonucleotides were synthesized on Pharmacia instruments (Gene Assembler Plus) following DNA/RNA standard methods using 2′-TOM protected phosphoramidite nucleoside building blocks. RNA oligonucleotides were deprotected by using CH3NH2 in EtOH (8 M, 0.65 mL) and CH3NH2 in H2O (40%, 0.65 mL) at room temperature for 6–8 h. After complete evaporation of the solution, the 2′-O-TOM protecting groups were removed by treatment with tetrabutylammonium fluoride trihydrate (TBAF•3H2O) in THF (1 M, 1.0–1.5 mL) for at least 14 h at 37 °C. The reaction was quenched by addition of triethylammonium acetate (1 M, pH 7.0, 1.0–1.5 mL). The volume of the solution was reduced to 0.8 mL and the solution was loaded on a GE Healthcare HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (2.6 × 10 cm; Sephadex G25). The crude RNA was eluted with H2O, evaporated to dryness and dissolved in 1.0 mL of nanopure water. Analysis of crude oligonucleotides after deprotection was performed by anion-exchange chromatography on a Dionex DNAPac100 column (4 × 250 mm) at 80 °C. Flow rate: 1 mL/ min; eluant A: 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 6 M urea; eluant B: 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaClO4, 6 M urea; gradient: 0–40% B in A within 30 min (< 20 nt) or 0–60% B in A within 45 min (> 20 nt); UV-detection at 260 nm. Crude RNA products (trityl-off) were purified on a semipreparative Dionex DNAPac100 column (9 × 250 mm) at 80 °C. Flow rate: 2 mL/ min; gradient: Δ5-10% B in A within 20 min. Fractions containing oligonucleotide were loaded on a C18 SepPak cartridge (Waters/Millipore), washed with 0.1 M  and H2O, eluted with H2O/CH3CN 1/1 and lyophilized to dryness. The purified oligonucleotides were characterized by mass spectrometry on a Finnigan LCQ Advantage MAX ion trap instrumentation connected to an Amersham Ettan micro LC system (negative-ion mode with a potential of -4 kV applied to the spray needle). LC: Sample (200 pmol of oligonucleotide dissolved in 30 μL of 20 mM EDTA solution; average injection volume: 30 μL); column (Amersham μRPC C2/C18; 2.1 × 100 mm) at 21 °C; flow rate: 100 μL/ min; eluant A: 8.6 mM TEA, 100 mM 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol in H2O (pH 8.0); eluant B: methanol; gradient: 0–100% B in A within 30 min; UV detection at 254 nm.

and H2O, eluted with H2O/CH3CN 1/1 and lyophilized to dryness. The purified oligonucleotides were characterized by mass spectrometry on a Finnigan LCQ Advantage MAX ion trap instrumentation connected to an Amersham Ettan micro LC system (negative-ion mode with a potential of -4 kV applied to the spray needle). LC: Sample (200 pmol of oligonucleotide dissolved in 30 μL of 20 mM EDTA solution; average injection volume: 30 μL); column (Amersham μRPC C2/C18; 2.1 × 100 mm) at 21 °C; flow rate: 100 μL/ min; eluant A: 8.6 mM TEA, 100 mM 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol in H2O (pH 8.0); eluant B: methanol; gradient: 0–100% B in A within 30 min; UV detection at 254 nm.

The 2 aminopurine containing RNAs of 61 nt and 70 nt length were prepared by splinted enzymatic ligation of the two chemically synthesized fragments using T4 DNA ligase as described in detail in SI Text.

NMR Experiments.

1H NMR imino proton spectra were recorded on a Varian Unity 500 MHz instrument and applied a selective excitation refocusing sequence employing selective pulses shaped according to the G4 (excitation; 2.62 ms, RF amplitude 1.74 kHz) and REBURP (refocusing; 1.4 ms, RF amplitude 4.47 kHz) profile, respectively (18, 41, 42). Both shaped pulses were centered at 13 ppm. 19F NMR spectra without 1H-decoupling were recorded at a frequency of 470.3 MHz on a Varian Inova 500 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm Indirect Detection PFG probe. Typical experimental parameters were chosen as follows: spectral width 14 kHz, 19F excitation pulse 12.4 μs, acquisition time 2.0 s, relaxation delay 2.0 s, number of scans 2048. 19F resonances were referenced relative to external CCl3F.

Typical NMR sample preparation: The RNA probe (triethyl ammonium salts) was lyophilized and dissolved in water, the corresponding amount of arsenate buffer stock solution (pH 6.5) and D2O was added to a total volume of 500 μL. RNA/preQ1 complex: The aliquots of a 25 mM aqueous solution of preQ1 and a 300 mM solution of MgCl2 were directly added to the NMR sample of the free RNA. Final concentrations were as indicated in the corresponding figure captions. All samples were heated to 90 °C for 1 min, then rapidly cooled in an ice bath and equilibrated to room temperature for 15 min before measurements.

Fluorescence Spectroscopic Experiments.

All experiments were measured on a Cary Eclipse spectrometer (Varian) equipped with a peltier block, a magnetic stirring device, and a RX2000 stopped-flow apparatus (Applied Photophysics Ltd.).

Binding affinities.

Using quartz cuvettes equipped with a small stir bar, RNA samples were prepared in 0.5 μM concentration in a total volume of 1 mL of buffer [50 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid potassium salt (KMOPS) pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2]. The samples were heated to 90 °C for 2 min, allowed to cool to room temperature, and held at 25 °C in the peltier controlled sample holder. Then, preQ1 was manually pipetted in 1 μL aliquots in a way not to exceed a total volume increase of 2%. The solution was stirred during each titration step and allowed to equilibrate for at least 15 min before data collection. Spectra were recorded from 320–500 nm using the following instrumental parameters: excitation wavelength, 308 nm; increments, 1 nm; scan rate, 120–300 nm/ min; slit widths, 10 nm. The apparent binding constants KD were determined by following the decrease in fluorescence after each titration step via integration of the area between 330 and 450 nm. Changes in fluorescence (F-F0) were normalized to the maximum fluorescence measured in the absence of preQ1. The measurement for each titration step was repeated at least three times and the mean of the normalized fluorescence intensity was plotted against the preQ1 concentration. Data were fit using a KD quadratic equation solution for 1∶1 stoichiometry provided in SI Text (28). The final KD value is an arithmetic mean, determined from three independent titration experiments.

Rate constants.

Rate constants k for individual riboswitch Ap variants (A33Ap 34 nt; A33Ap 61 nt; A33Ap 70 nt) were measured under pseudo-first-order conditions with preQ1 in excess over RNA. Stock solutions were prepared for each Ap variant (concentration cRNA = 1.0 μM in 50 mM KMOPS pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2) and for preQ1 (concentration cpreQ1 = 4 to 22 μM in 50 mM KMOPS pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2). Mixing equal volumes of these stock solutions via the stopped-flow apparatus resulted in a final concentration of 0.5 μM RNA and of 2 to 11 μM preQ1. Spectra were recorded at 25 °C using the following instrumental parameters: excitation wavelength, 308 nm; emission wavelength, 372 nm; increment of data point collection, 0.0375 s; slit widths, 10 nm. The stopped-flow fluorescence data were fit to a single-exponential equation: F = A1 + A2e-k′t (A1 initial fluorescence, A2 e-k′t change in fluorescence over time t at the observed rate k′). The measurement for each concentration was repeated at least three times and the mean of the observed rates k′ was plotted against preQ1 concentration to obtain the rate constant k from the slope of the plot. The final rate constant k value is an arithmetic mean, determined from three independent stopped-flow measurements. All data processing was performed using Kaleidagraph software (Synergy Software).

Native Gel Shift Assays and Chemical and Enzymatic Probing Experiments.

Detailed experimental procedures are available in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Andrea Haller (University of Innsbruck), Norbert Polacek (Medical University Innsbruck), and Daniel N. Wilson (Gene Center, University of Munich) for discussions. Funding by the Austrian Science Foundation Fonds zur Fö¨rderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung (FWF) (Projects I317 and P21641) and the Ministry of Science and Research (GenAU Project “Noncoding RNAs,” P0726-012-012) is acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.0914925107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Serganov A. The long and the short of riboswitches. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montange RK, Batey RT. Riboswitches: Emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Ann Rev Biophys. 2008;37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth A, Breaker RR. The structural and functional diversity of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070507.135656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serganov A, Patel DJ. Ribozymes, riboswitches and beyond: Regulation of gene expression without proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:776–790. doi: 10.1038/nrg2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blouin S, Mulhbacher J, Penedo JC, Lafontaine DA. Riboswitches: Ancient and promising genetic regulators. Chembiochem. 2009;10:400–416. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwalbe H, Buck J, Fürtig B, Noeske J, Wöhnert J. Structures of RNA switches: Insight into molecular recognition and tertiary structure. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:1212–1219. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nudler E, Mironov AS. The riboswitch control of bacterial metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dambach MD, Winkler WC. Expanding roles for metabolite-sensing regulatory RNAs. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henkin TM. Riboswitch RNAs: Using RNA to sense cellular metabolism. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3383–3390. doi: 10.1101/gad.1747308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth A, et al. A riboswitch selective for the queuosine precursor preQ1 contains an unusually small aptamer domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:308–317. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klepper F, Polborn K, Carell T. Robust synthesis and crystal-structure analysis of 7-cyano-7-deazaguanine (PreQ(0) base) and 7-(aminomethyl)-7-deazaguanine (PreQ(1) base) Helv Chim Acta. 2005;88:2610–2616. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieder U, Lang K, Kreutz C, Polacek N, Micura R. Evidence for pseudoknot formation of class I preQ1 riboswitch aptamers. Chembiochem. 2009;10:1141–1144. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein DJ, Edwards TE, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Cocrystal structure of a class I preQ1 riboswitch reveals a pseudoknot recognizing an essential hypermodified nucleobase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:343–344. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang M, Peterson R, Feigon J. Structural insights into riboswitch control of the biosynthesis of queuosine, a modified nucleotide found in the anticodon of tRNA. Mol Cell. 2009;33:784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitale RC, Torelli AT, Krucinska J, Bandarian V, Wedekind JE. The structural basis for recognition of the PreQ0 metabolite by an unusually small riboswitch aptamer domain. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11012–11016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C900024200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buck J, Fürtig B, Noeske J, Wöhnert J, Schwalbe H. Time-resolved NMR methods resolving ligand-induced RNA folding at atomic resolution. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15699–15704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703182104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Hashimi HM, Walter NG. RNA dynamics: It is about time. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Höbartner C, Micura R. Bistable secondary structures of small RNAs and their structural probing by comparative imino proton NMR spectroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:421–431. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Micura R, Höbartner C. On secondary structure rearrangements and equilibria of small RNAs. Chembiochem. 2003;4:984–990. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Höbartner C, Mittendorfer H, Breuker K, Micura R. Triggering of RNA secondary structures by a functionalized nucleobase. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3922–3925. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelissen FH, et al. Multiple segmental and selective isotope labeling of large RNA for NMR structural studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tzakos AG, Easton LE, Lukavsky PJ. Preparation of large RNA oligonucleotides with complementary isotope-labeled segments for NMR structural studies. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2139–2147. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puffer B, et al. 5-Fluoro pyrimidines: labels to probe DNA and RNA secondary structures by 1D 19F NMR spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7728–7740. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreutz C, Kählig H, Konrat R, Micura R. Ribose 2′-F labeling: A simple tool for the characterization of RNA secondary structure equilibria by 19F NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11558–11559. doi: 10.1021/ja052844u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graber D, Moroder H, Micura R. 19F NMR spectroscopy for the analysis of RNA secondary structure populations. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17230–17231. doi: 10.1021/ja806716s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreutz C, Kählig H, Konrat R, Micura R. A general approach for the identification of site-specific RNA binders by 19F NMR spectroscopy: proof of concept. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3450–3453. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rieder R, Lang K, Graber D, Micura R. Ligand-induced folding of the adenosine deaminase A-riboswitch and implications on riboswitch translational control. Chembiochem. 2007;8:896–902. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang K, Rieder R, Micura R. Ligand-induced folding of the thiM TPP riboswitch investigated by a structure-based fluorescence spectroscopic approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5370–5378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lang K, Micura R. The preparation of site-specifically modified riboswitch domains as an example for enzymatic ligation of chemically synthesized RNA fragments. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1457–1466. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winkler WC, Nahvi A, Sudarsan N, Barrick JE, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding S-adenosylmethionine. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:701–707. doi: 10.1038/nsb967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemay JF, Penedo JC, Tremblay R, Lilley DM, Lafontaine DA. Folding of the adenine riboswitch. Chem Biol. 2006;13:857–868. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wickiser JK, Cheah MT, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. The kinetics of ligand binding by an adenine-sensing riboswitch. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13404–13414. doi: 10.1021/bi051008u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wickiser JK, Winkler WC, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. The speed of RNA transcription and metabolite binding kinetics operate an FMN riboswitch. Mol Cell. 2005;18:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilbert SD, Stoddard CD, Wise SJ, Batey RT. Thermodynamic and kinetic characterization of ligand binding to the purine riboswitch aptamer domain. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:754–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith KD, et al. Structural basis of ligand binding by a c-di-GMP riboswitch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1218–1223. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulshina N, Baird NJ, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Recognition of the bacterial second messenger cyclic diguanylate by its cognate riboswitch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1212–1217. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adelman K, et al. Single molecule analysis of RNA polymerase elongation reveals uniform kinetic behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13538–13543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212358999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tolić-Nørrelykke SF, Engh AM, Landick R, Gelles J. Diversity in the rates of transcript elongation by single RNA polymerase molecules. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3292–3299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nygaard P, Saxild HH. The purine efflux pump PbuE in Bacillus subtilis modulates expression of the PurR and G-box (XptR) regulons by adjusting the purine base pool size. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:791–794. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.791-794.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong TN, Pan T. RNA folding during transcription: Protocols and studies. Methods Enzymol. 2009;468:167–193. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)68009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley L, Bodenhausen G. Gaussian pulse cascades: New analytical functions for rectangular selective inversion and in-phase excitation in NMR. Chem Phys Lett. 1990;165:469–476. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geen H, Freeman R. Band-selective radiofrequency pulses. J Magn Reson. 1991;93:93–141. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.