Abstract

The cerebellar rhombic lip and telencephalic cortical hem are dorsally located germinal zones which contribute substantially to neuronal diversity in the CNS, but the mechanisms that drive neurogenesis within these zones are ill defined. Using genetic fate mapping in wild-type and Lmx1a−/− mice, we demonstrate that Lmx1a is a critical regulator of cell-fate decisions within both these germinal zones. In the developing cerebellum, Lmx1a is expressed in the roof plate, where it is required to segregate the roof plate lineage from neuronal rhombic lip derivatives. In addition, Lmx1a is expressed in a subset of rhombic lip progenitors which produce granule cells that are predominantly restricted to the cerebellar posterior vermis. In the absence of Lmx1a, these cells precociously exit the rhombic lip and overmigrate into the anterior vermis. This overmigration is associated with premature regression of the rhombic lip and posterior vermis hypoplasia in Lmx1a−/− mice. These data reveal molecular organization of the cerebellar rhombic lip and introduce Lmx1a as an important regulator of rhombic lip cell-fate decisions, which are critical for maintenance of the entire rhombic lip and normal cerebellar morphogenesis. In the developing telencephalon Lmx1a is expressed in the cortical hem, and in its absence cortical hem progenitors contribute excessively to the adjacent hippocampus instead of producing Cajal-Retzius neurons. Thus, Lmx1a activity is critical for proper production of cells originating from both the cerebellar rhombic lip and the telencephalic cortical hem.

Keywords: cell-fate specification, cerebellum, development, neuronal progenitors, telencephalon

During development of the CNS, neurons are generated in germinal zones and then migrate to their final destinations. Numerous studies have focused on the regulation of neurogenesis in germinal zones which distribute neurons through a radial mode of migration, such as ventricular zones in the developing spinal cord or telencephalon (1–3). Much less is understood, however, regarding neurogenesis in germinal zones that distribute neurons tangentially, such as the cerebellar rhombic lip (RL) and telencephalic cortical hem (CH) (4). Both the RL and CH are dorsomedially located, border a choroid plexus (CP), and define the edges of a neuroepithelium. They share graded Bmp and Wnt signaling, and both generate neuronal populations that migrate along the surface of the adjacent anlagen (3, 5, 6).

The cerebellar RL is located in dorsal rhombomere 1 (rh1) (7, 8). It gives rise to multiple cell types including cerebellar neurons and neurons of the precerebellar system and also contributes to the adjacent fourth ventricle roof plate (RP) and its later derivative, the CP (9–16). RL derivatives arise in distinct, although partially overlapping, cohorts. In the mouse, neurons of deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN) are generated in the RL between embryonic days (e) 10 and 12. They are followed at e13.5 by granule neuron progenitors which will populate the anterior cerebellum and later by granule neuron progenitors which will occupy the posterior cerebellum (17, 18). Unipolar brush cells (UBC) begin to exit the RL around e15.5 (19). In contrast to many other germinal zones which disappear during late embryogenesis, the RL remains active through early postnatal life. Currently little is understood regarding how the cell fates of RL derivatives are established, when and how their eventual positions in the adult cerebellum are determined, or what determines the longevity of the RL.

The telencephalic CH, located between the CP and hippocampal field, is a major source of Cajal-Retzius neurons, which migrate tangentially and serve to organize the cerebral cortex (3). The mechanisms that regulate neurogenesis within the CH are poorly understood, and it is unknown if they are related in any way to those operating in the RL.

Using genetic fate mapping and mutant analysis, we identified the LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Lmx1a as the first essential regulator of cell-fate decisions common to the cerebellar RL and the telencephalic CH. To date, Lmx1a has been implicated in induction of the nonneural RP in the dorsal neural tube (5, 20, 21) and differentiation of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral midbrain (22). The results of our current study indicate that, in addition, Lmx1a is a major regulator of neurogenesis in dorsal brain germinal zones.

Results

Lmx1a Is Expressed in a Subset of Cerebellar Rhombic Lip Progenitors.

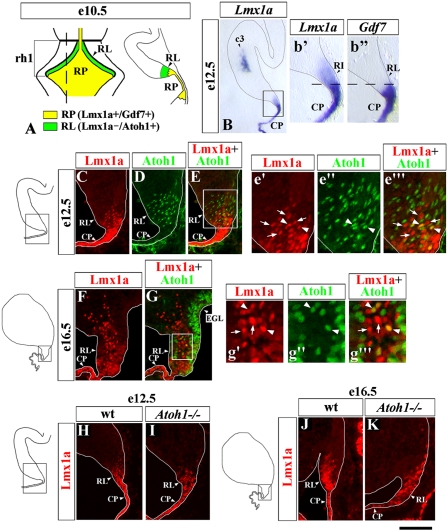

Previously, in early rh1, Lmx1a was established as a specific marker of the RP, where, at e10.5, it is coexpressed with Gdf7 (Fig. 1A) (5). By e12.5, however, Lmx1a expression clearly extends into the adjacent cerebellar RL, whereas Gdf7 remains restricted to the RL-derived CP (Fig. 1B, b′, and b′′). To study Lmx1a expression in the RL in more detail, we compared expression of this gene with that of Atoh1, a marker proposed to define the entire RL population (18). Interestingly, at both e12.5 and e16.5, although some Lmx1a+ cells coexpressed Atoh1, many Lmx1a+ RL cells were Atoh1− (Fig. 1 C–G), revealing molecular heterogeneity in the RL. Furthermore, Lmx1a still was expressed in Atoh1−/− embryos at both e12.5 and e16.5 (Fig. 1 H–K), suggesting that Lmx1a RL expression is not dependent on Atoh1.

Fig. 1.

Lmx1a is expressed in the cerebellar RL independently of Atoh1. (A) Summary of Lmx1a expression in rh1 at e10.5 (5). Dorsal view of the anterior hindbrain (Left) and a sagittal section (Right) at the level of the dashed line in the dorsal view. (B–G) In situ and immunostained (C–G) sagittal sections of the cerebellar anlage at the indicated stages; b′–b′′, e′–e′′′ and g′–g′′′ show higher magnification of boxed regions in B, E, and G, respectively. Arrows point to Lmx1a+/Atoh1− cells; arrowheads point to rare Lmx1a+/Atoh1+ cells in the RL. (H–K) Lmx1a-immunostained sagittal sections of wild-type (H and J) and Atoh1−/− (I and K) embryos at the indicated stages. Lmx1a expression is present in the RL of Atoh1−/− embryos. (Scale bar: B, 300 μm; b′ and b′′, 100 μm; C–E and F–G, 50 μm; e′–e′′ and g′–g′′′, 20 μm; H and I, 150 μm; J and K, 75 μm.)

Notably, Lmx1a expression also was detected in three additional cellular populations in the cerebellum outside the RL and RP. These include “c3” cells (5), which initiate Lmx1a expression around e12.5 (Fig. 1B). They do not originate from the RL (Fig. S1 A–C), and their identity is unknown. The remaining two groups of Lmx1a+ cells represent RL derivatives based on β-gal labeling in Atoh1LacZ/+ mice. The first group appears in the nuclear transitory zone at e13.5, suggesting that these cells are glutamatergic neurons of DCN (12) (Fig. S1 A–C). The other Lmx1a+ population is UBC, based on their migration pattern, anatomical location, and expression of Tbr2 (19) (Fig. S1 D–I).

Thus, in addition to the fourth ventricle RP, in rh1 Lmx1a is expressed in several other cellular populations, including a subset of RL progenitors. Our data highlight molecular heterogeneity in the cerebellar RL and introduce Lmx1a as an Atoh1-independent RL gene.

Tools to Study Lmx1a Function in Lmx1a-Expressing Cells and Their Progeny.

In this study we performed detailed analysis of two Lmx1a-expressing populations in developing rh1: (i) the fourth ventricle RP/CP and (ii) Lmx1a+ cells in the cerebellar RL. To determine if Lmx1a function is required for proper development of these cells, we used the dreher (Lmx1a−/−) mouse. In dreher mice, Lmx1a is inactivated by a missense mutation (20). Both mutant mRNA and protein are produced and can be detected by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry, allowing precise identification of Lmx1a-expressing cells in dreher mice (5, 21).

To visualize the progeny of Lmx1a+ cells in the developing rh1 directly, we developed a Lmx1a-Cre fate-mapping system. We generated a Lmx1a-Cre BAC transgenic mouse line in which expression of an eGFP-tagged Cre protein (GFP-Cre) was controlled by Lmx1a regulatory elements (referred to herein as “Lmx1a-Cre”). Double Lmx1a/GFP antibody staining revealed that in Lmx1a-Cre mice, GFP-Cre expression recapitulated that of Lmx1a in the fourth ventricle RP and CP, RL, c3 cells, and UBC (Figs. S2 A–G, M, and N and S3 A–C and H–J). No GFP expression was detected in DCN (Fig. S2 C and D). No ectopic expression of GFP in the cerebellar anlage was detected at any stage.

Next we analyzed our Lmx1a-Cre system on the dreher background. No differences in Lmx1a or Cre expression were detected between wild-type and dreher Lmx1a-Cre mice in any cerebellar population (Figs. S2 and S3) except in UBC, where both Lmx1a and Cre expression were lost in dreher mice (Fig. S2 M–P). Therefore, our Lmx1a-Cre mouse line is suitable to map the fates of several Lmx1a+ populations in the developing cerebellar anlage, including the fourth ventricle RP and Lmx1a+ RL cells. This system also can be used in dreher mice to study how loss of Lmx1a function affects the development of these cells and their progeny.

In rh1, Lmx1a Is Required to Segregate the Roof Plate/Choroid Plexus Lineage from Neuronal Rhombic Lip Derivatives.

First we analyzed the role of Lmx1a in the development of the fourth ventricle RP. The dreher fourth ventricle RP is small, and we previously suggested that Lmx1a is required for its normal induction (5, 20). However, our present detailed analysis revealed no significant differences in size between RP of wild-type and dreher embryos at e9.25 (Fig. 2 A and B), although by e10.5 the dreher RP was indeed much smaller than wild-type RP (Fig. 2 C and D). These data suggest that Lmx1a actually is dispensable for induction of the fourth ventricle RP but instead is required for its normal growth.

Fig. 2.

A switch in cell fate causes RP reduction in dreher mice. (A–D) Wild-type (A and C) and dreher (dr/dr; B and D) embryos stained with RP markers. Arrows point to fourth ventricle RP, which is induced in dreher embryos but does not grow properly. (E–H) Lineage analysis of RP cells in wild-type (E and F) and dreher (G and H) embryos using the Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA alleles. Insets (F, H) show higher magnification of RLS. In dreher mutants, some RP cells lose their identity and migrate into the cerebellar anlage (G, arrow). These β-gal+ cells could be labeled by an anti-Lhx2/9 antibody (Inset in H, arrowheads), which specifically marks RLS cells (5). (I and J) Lineage analysis of RP cells using the Gdf7-Cre/ROSA alleles. Sagittal sections of adult wild-type (I) and dreher (J) vermis stained for β-gal activity. In the wild-type Gdf7-Cre/ROSA cerebellum, β-gal staining is limited mostly to the CP (i′). In the dreher;Gdf7-Cre/ROSA cerebellum, ectopic β-gal+ cells are present in DCN (arrowheads) and IGL of the posterior vermis (arrow) (j′). (K) Diagram summarizing a switch in fate of RP cells in dreher mice. In wild-type mice, RP (red) produces CP. In dreher mice RP aberrantly produces neurons of DCN and granule cells and UBC of posterior vermis. (Scale bar: A and B, 800 μm; C and D, 1.75 mm; E–H, 180 μm; I and J, 870 μm; i′ and j′, 410 μm.)

To determine the basis of the dreher RP phenotype, we used fate mapping. By crossing Lmx1a-Cre mice with a ROSA26 reporter strain, which labels Cre+ cells and their progeny with β-gal expression, we labeled Lmx1a+ RP cells. At e10.5, in wild-type Lmx1a-cre/ROSA embryos, β-gal+ cells were located primarily in the RP (Fig. 2E). Strikingly, in dreher littermates, many β-gal+ cells were located on the dorsal surface of the cerebellar anlage (Fig. 2G, arrow). These ectopic cells were recognized by an anti-Lhx2/9 antibody (Fig. 2 F and H), a marker of the rostral RL migratory stream (RLS) (5), which normally originates from the RL and gives rise to glutamatergic neurons of DCN (18). Therefore, our data suggest that, in the absence of Lmx1a function, by e10.5 some RP cells aberrantly adopt the fate of the RLS/DCN lineage.

After e10.5, in rh1, Lmx1a expression is no longer limited to the RP/CP, making it difficult to fate map the RP lineage specifically using the Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA system at later developmental stages. To characterize better the specific contribution of the RP lineage to the dreher cerebellum, we therefore turned to the Gdf7-Cre/ROSA fate-mapping system (23), because, unlike Lmx1a, Gdf7 expression remains restricted to the RP/CP throughout development (24). In postnatal wild-type Gdf7-Cre/ROSA mice, RP-originating β-gal+ cells were located primarily in the CP and were not found in the cerebellum. Analysis of dreher Gdf7-Cre/ROSA mice revealed that, in the absence of Lmx1a function, RP/CP contributed to multiple RL-derived neuronal lineages, including neurons of DCN as well as granule cells and UBC, located mostly in the posterior vermis (Fig. 2 I and J and Fig. S4). Thus, our data indicate that Lmx1a activity is essential to prevent the RP/CP lineage from adopting the fate of RL-derived cerebellar neurons (summarized in Fig. 2K).

Lmx1a Is Critical for Maintenance of the Cerebellar Rhombic Lip and Building the Posterior Vermis.

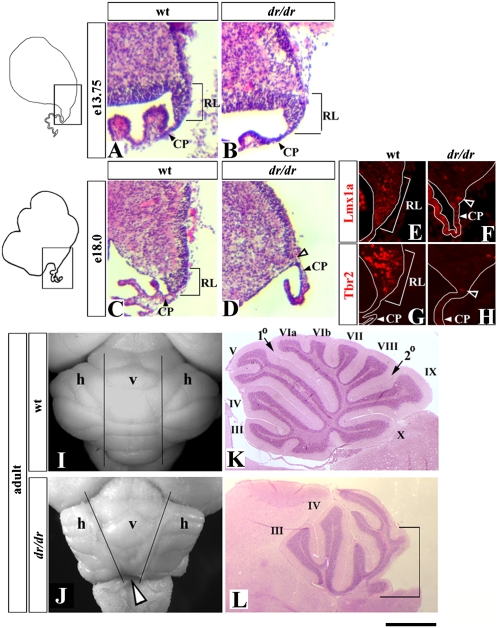

Expression of Lmx1a in the cerebellar RL beginning at e12.5 suggested a role for this gene in RL development beyond its role in the RP lineage. We, therefore, examined RL morphology in wild-type and dreher mice. At e13.75 the RL in dreher mice was not significantly different from that of wild-type embryos (Fig. 3 A and B). However, it gradually became smaller as development proceeded. By e18.0, no RL was present in the dreher cerebellum (Fig. 3 C and D), as confirmed by loss of Lmx1a and Tbr2 staining (Fig. 3 E–H). Because the late RL produces cells that contribute to the posterior vermis (17), we predicted that this domain of the adult dreher cerebellum would be affected specifically. Indeed, although the entire cerebellum was abnormal in dreher mutants, we consistently observed predominant posterior vermis hypoplasia in adult dreher mice (Fig. 3 I–L). Lmx1a, therefore, is required for maintenance of the RL and posterior vermis morphogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Premature regression of the RL and posterior vermis hypoplasia in dreher mice. (A–H) Sagittal sections of medial cerebellar anlage of wild-type (A, C, E, and G) and dreher (B, D, F, and H) embryos stained with H&E (A–D) or with indicated antibodies (E–H) at the indicated stages. In dreher embryos, RL was present at e13.75, but virtually no RL was detected in these embryos at e18.0 (D, open arrowhead). (E–H) Only RL and adjacent CP are shown. Open arrowheads in F and H point to a few Lmx1a+ and Tbr2+ cells occasionally found in the area corresponding to the dreher RL. (I–L) Dorsal whole mount views (I and J) and midsagittal sections (K and L) of wild-type (I and K) and dreher (J and L) cerebella. (I and J) Vertical lines distinguish vermis (v) from hemispheres (h) in wild-type. In the dreher cerebellum (J) the posterior vermis is reduced (open arrowhead). (K and L) Vermis folia are indicated by roman numerals. The predominant reduction of the posterior vermis (marked by bracket) is obvious in the dreher cerebellum. (Scale bar: A–D, 100 μm; E–H, 50 μm; I and J, 2 mm; K and L, 1 mm.)

Lmx1a-Dependent Cell-Fate Decisions Are Critical for Proper Exit of Granule Progenitors from the Rhombic Lip and Their Precise Location in the Adult Cerebellum.

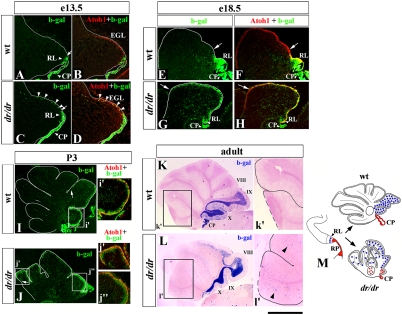

To address the cellular mechanisms that underlie the RL abnormalities and posterior vermis hypoplasia in dreher mice, we returned to our Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA fate-mapping system to study Lmx1a+ RL derivatives during development. In wild-type Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA embryos, before e18.5, most β-gal+ cells were located in the RL (Fig. 4 A, B, E, and F). At e18.5, some β-gal+ cells began entering the external granule cell layer (EGL), where they expressed Atoh1 (Fig. 4 E and F), suggesting that they adopted the fate of granule cell progenitors. By P3, Atoh1+/β-gal+ cells extended to the boundary between future lobes VIII and IX in wild-type mice (Fig. 4I, arrow). In adult Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA cerebella there was strong β-gal signal in the posterior vermis internal granule layer (IGL), limited mostly to lobes IX and X (Fig. 4K). These data suggest that after postnatal day (P) 3, the β-gal+ granule cells originating from Lmx1a+ progenitors do not continue their anterior migration and eventually populate lobes IX and X of the posterior vermis.

Fig. 4.

Abnormal distribution of granule cells originating from Lmx1a+ progenitors in the dreher cerebellum. Midsagittal sections of wild-type (A, B, E, F, I, and K) and dreher (C, D, G, H, J, and L) cerebella containing the Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA fate-mapping system at the indicated stages. Sections were stained with indicated antibodies (A–J) or were stained for β-gal activity (K and L). (A–D) Arrows point to the anterior limit of the RL in wild-type (A) and dreher (C) embryos. Arrowheads point to numerous β-gal+ cells migrating along the dorsal surface of the dreher (C and D) but not wild-type (A abd B) cerebellar anlage at e13.5. (E–J) Arrows indicate the anterior limit of β-gal+ cells in wild-type and dreher EGL. At both e18.5 and P3, β-gal+ cells extend much more into the anterior cerebellum in dreher mice than in their wild-type littermates. At all developmental stages, β-gal+ cells in both wild-type and dreher EGL express Atoh1 (D, F, H, I, i′, J, j′, and j′′), indicating that they are granule progenitors. (K and L) In adult wild-type vermis, β-gal+ cells predominantly populate posterior lobes IX and X (K). In dreher mice, numerous β-gal+ cells abnormally populate the intermediate and anterior vermis (L). Arrowheads (l′) point to ectopic β-gal+ cells in anterior IGL in ′adult dreher mice. (M) Diagram summarizing distribution of granule cells originating from Lmx1a+ RL progenitors in wild-type and dreher mice. Normally these cells (blue circles) contribute to posterior vermis. In dreher mice they overmigrate into intermediate and anterior vermis. (RP derivatives are shown in red. Fig. 2K gives a detailed description). (Scale bar: A–D, 290 μm; E–H, 530 μm; I and J, 420 μm; i′ and j′, 200 μm; K and L, 1.5 mm; k′ and l′, 750 μm.)

Loss of Lmx1a significantly affected the development of granule cells in dreher mice. Although we observed no abnormalities in the kinetics of EGL formation in dreher mice, dramatic differences were detected in the accumulation of the β-gal+ fraction in the EGL of dreher Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA embryos. In particular, in dreher Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA embryos, a stream of β-gal+ cells extending from the RL into the EGL was observed as early as e13.0–e13.5 (Fig. 4 C and D), and by e18.5 most β-gal+ cells already had migrated into the EGL in these embryos (Fig. 4 G and H). By P3, in dreher mutants, β-gal+ cells occupied the EGL along its entire anterior–posterior axis (Fig. 4J). At every stage investigated, β-gal+ cells in the EGL of dreher Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA mice maintained their granule cell identity as revealed by Atoh1 expression (Fig. 4 D, H, j′, and j′′). As predicted from the developmental analysis, in adult dreher Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA cerebella, β-gal+ cells were distributed ectopically in the IGL of anterior and intermediate lobes of the mutant vermis (Fig. 4L).

Together, our data suggest that Lmx1a+ cells in the RL normally generate granule progenitors that exit the RL during late embryogenesis and predominantly contribute to the posterior vermis. In the absence of Lmx1a, these progenitors exit the RL prematurely and migrate ectopically into the anterior vermis (summarized in Fig. 4M).

Lmx1a Acts Intrinsically in the Rhombic Lip to Prevent Premature Exit of Granule Cell Progenitors.

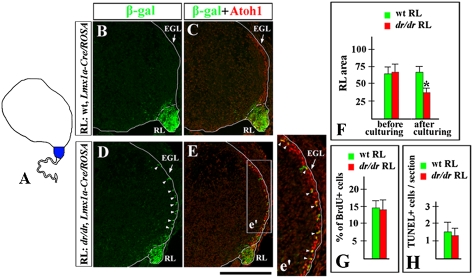

Two explanations could account for the premature migration of granule cells from the dreher mutant RL. First, Lmx1a might act within the RL to prevent the premature exit of granule cell progenitors. Second, the migratory phenotype may be non-cell autonomous, because in rh1 Lmx1a also is expressed in other cellular populations, including the CP, and the CP is clearly affected in dreher embryos. To distinguish between these possibilities, we performed cerebellar slice coculture experiments. We used slices of wild-type (nontransgenic) cerebellar anlage, in which the host RL was replaced by equivalent RL tissue from a donor wild-type or dreher embryo, allowing cells to migrate between tissues (19). The replacement RL also carried the Lmx1a-cre/ROSA reporter alleles to mark the Lmx1a+ RL population and its progeny (Fig. 5A). Both wild-type host embryos and donor wild-type or dreher embryos were harvested at e12.75, just before EGL formation. After 2 days in culture, most β-gal+ cells in slices containing wild-type RL were still located in the RL (Fig. 5 B and C). In contrast, many β-gal+ cells in slices containing dreher RL had entered the EGL, similar to the general granule cell progenitor pool (Fig. 5 D and E), even in the presence of wild-type cerebellar anlage and CP. Our data therefore suggest that Lmx1a in the RL cell-autonomously inhibits premature migration of Lmx1a+ progenitors from the RL into the EGL.

Fig. 5.

Lmx1a acts intrinsically in the RL to regulate proper exit of granule cell progenitors. (A) Slice coculture experiments in which the RL of a wild-type nontransgenic embryo (host, white) was replaced by the RL of a wild-type or dreher embryo carrying the Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA alleles (donor, blue). (B–E) Sections of explants stained with indicated antibodies. In explants that contain dreher Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA RL, numerous β-gal+ cells migrate abnormally into the EGL (D, arrowheads). These cells coexpress Atoh1 (arrowheads in e′) and, therefore, are granule cell progenitors. (F) Quantification of the area of wild-type (n = 12) and dreher (dr/dr) (n = 9) RL before and after culturing with wild-type cerebellar slices. Although equally sized RL pieces were used at the beginning of culture experiments, dreher RL became smaller than wild-type RL after 2 days in culture. Error bars represent SD. *, P < 0.001. (G and H) No difference in proliferation or apoptosis was detected between wild-type and dreher RL explants after 2 days in culture. (G) Percent of BrdU+ cells in wild-type (n = 4) and dreher (n = 4) RL. (H) Number of TUNEL+ cells per section in wild-type (n = 9) and dreher (n = 9) RL. Error bars represent SD. (Scale bar: B–E, 220 μm; e′, 110 μm.)

Precocious granule progenitor migration was not the only phenotype observed in our explants. Although comparably sized pieces of wild-type and dreher RL initially were transplanted into host wild-type cerebellar anlage slices, after 2 days in culture the explanted dreher RL was significantly smaller than the explanted wild-type RL (P < 0.001, Fig. 5F). Neither proliferation nor apoptosis was significantly different between the wild-type and dreher RL explants after 2 days in culture (Fig. 5 G and H). Thus, precocious migration of Lmx1a+ progenitors from the RL may contribute to the premature reduction of the dreher RL.

Recent Atoh1 fate-mapping experiments have demonstrated that, once cells initiate Atoh1 expression, they exit the RL (17). We hypothesized that Lmx1a may prevent premature migration of RL progenitors, at least partially, by repressing Atoh1 expression. We compared the proportion of Lmx1a+ cells expressing Atoh1 in e13.75 wild-type and dreher RL and observed a significant increase in the number of Lmx1a+/Atoh1+ cells in the RL in dreher versus wild-type embryos (P < 0.01) (Fig. S5). These data support the hypothesis that up-regulation of Atoh1 in the Lmx1a lineage contributes to the precocious migration phenotype observed in the dreher RL.

Lmx1a also Regulates Cell-Fate Decisions in the Telencephalic Cortical Hem.

The telencephalic CH shares several features with the RL. As discussed earlier, CH is a dorsally located germinal zone that also expresses Lmx1a and produces tangentially migrating Cajal-Retzius cells (25). To determine if Lmx1a shares an analogous role in cell-fate specification in this dorsomedial zone, we extended our Lmx1a fate-mapping experiments to the dorsal developing telencephalon.

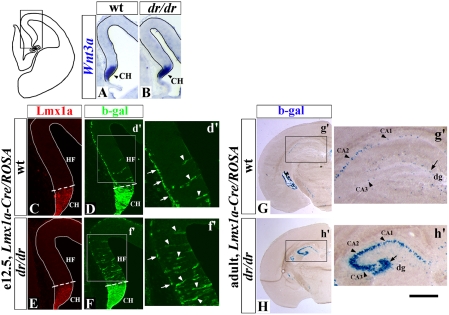

Our analysis of dreher mutants revealed that Lmx1a is not required for induction of the CH, because this structure was present in dreher embryos based on appropriate expression of a CH marker Wnt3a (26) (Fig. 6 A and B). However, significant cell fate abnormalities in the developing dreher telencephalon were detected using our Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA system.

Fig. 6.

Lmx1a regulates cell-fate decisions in the dorsal telencephalon. (A and B) Coronal hemisections of e12.5 wild-type (A) and dreher (B) telencephalon, which correspond to the boxed region in the diagram to the left, stained with Wnt3a in situ probe to visualize CH. CH is normally induced in dreher embryos. (C–H) Tracing progeny of Lmx1a+ cells in wild-type (C, D, and G) and dreher (E, F, and H) mice at indicated stages using the Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA alleles. Coronal hemisections are stained with indicated antibodies (C–F) or stained for β-gal activity (G and H). HF, hippocampal field. Limit of the Lmx1a expressing CH is shown by dotted line. In d′ and f′, Arrows point to β-gal+ Cajal-Retzius cells on the pial surface of wild-type (d′) and dreher (f′) telencephalon. In dreher telencephalon, they are reduced in numbers. Arrowheads point to β-gal+ cells within the hippocampal field. They are increased in dreher embryos. (G and H) Many more β-gal+ cells were detected in all hippocampal domains in adult dreher mice than in wild-type littermates. Arrows point to β-gal+ cells in the dentate gyrus (dg). Arrowheads point to β-gal+ cells in CA1–3 domains. (Scale bar: A and B, 240 μm; C–F, 150 μm; d′ and f′, 80 μm; G and H, 200 μm; g′ and h′, 450 μm.)

β-gal antibody staining of e12.5 Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA embryos revealed that normally, as expected, Lmx1a+ progenitors mostly give rise to Cajal-Retzius cells, which can be identified based on their location on the pial surface of the developing telencephalon and p73 expression (26) (Fig. 6d′, arrows and Fig S6A). In addition, a few β-gal+ cells were located within the adjacent hippocampal field (Fig. 6d′, arrowheads). Consistent with the observation of β-gal+ cells in the embryonic hippocampal field, in adult animals some β-gal+ cells also were detected in both the dentate gyrus and CA1–3 domains of the hippocampus (Fig. 6g′). In dreher Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA mice, many more β-gal+ cells were detected in the hippocampal field at e12.5 (arrowheads in Fig. 6 d′ and f′), and many more β-gal+ cells were detected subsequently in all hippocampal areas at P21 (Fig. 6 g′ and h′). These changes were associated with a significant decrease in the number of Cajal-Retzius cells in dreher embryos (P < 0.01) (arrows in Fig. 6 d′ and f′ and Fig. S6 B–D). There was no difference in Lmx1a or GFP-Cre expression between wild-type and dreher Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA mice (Fig. S7). Therefore, in dreher mice, Lmx1a+ progenitors contribute excessively to the adjacent hippocampus instead of producing Cajal-Retzius cells.

To address possible mechanisms that underlie the cell-fate changes in the dreher mutant dorsal telencephalon, we analyzed expression of Lhx2, a recently identified hippocampal selector gene (25). We found ectopic expression of this gene in the dreher CH at e10.5, with a more than 2-fold increase in the number of Lmx1a+/Lhx2+ double-positive cells compared with wild-type littermates (Fig. S8). This finding suggests that Lmx1a is required to repress expression of Lhx2 in the CH to prevent these cells from adopting hippocampal fates and to ensure normal production of Cajal-Retzius cells.

Discussion

In this study we have identified Lmx1a as a regulator of cell-fate decisions in the cerebellar RL and telencephalic CH. In dorsal rh1, Lmx1a is required to segregate the RP/CP lineage from neuronal RP derivatives to ensure the proper generation of fourth ventricle RP and CP. Additionally, Lmx1a acts in a subset of RL progenitors regulating their exit from the RL to restrict their fate to granule cells of the cerebellar posterior vermis. In the absence of Lmx1a, these cells exit the RL precociously and overmigrate into the anterior vermis. This overmigration is associated with premature RL regression and posterior vermis hypoplasia in dreher mice, demonstrating that Lmx1a-dependent cell-fate decisions are critical for the maintenance of the entire RL and appropriate adult cerebellar morphogenesis. In the telencephalic CH, Lmx1a activity is critical for proper production of Cajal-Retzius neurons instead of hippocampal cells.

Lmx1a Segregates the Fourth Ventricle Roof Plate Lineage from Neuronal Rhombic Lip Derivatives.

The fourth ventricle RP is a major signaling center that regulates cerebellar development, and its later derivative, the CP, produces the cerebrospinal fluid of the CNS (24). Previously, we have determined that the fourth ventricle RP and CP are reduced in dreher mice (5, 20), indicating that Lmx1a is required for development of these structures, although the mechanism was unknown. Using Lmx1a and Gdf7 fate mapping, we now show that, in the absence of Lmx1a, some cells of the RP/CP lineage lose their identity and migrate into the adjacent cerebellum, adopting the fate of RL-derived neurons, including neurons of DCN, and granule cells and UBC of the posterior vermis. Therefore, Lmx1a is required to segregate the RL/CH from neuronal RL derivatives. This misspecification of RP/CH cells results in a smaller fourth ventricle RP and CP in dreher mice. Because early RP signaling regulates early pan-cerebellar anlage proliferation (5), the reduced RP likely contributes to the ultimate small size of the dreher cerebellum.

Lmx1a-Dependent Cell-Fate Decisions Are Critical for Maintenance of the Cerebellar Rhombic Lip and Posterior Vermis Morphogenesis.

Previously, it was shown that all RL-derived neurons originate from Atoh1+ cells, leading to the classical definition of the RL as the Atoh1+ progenitor population (17, 18). In the current study we identified a class of Lmx1a+ RL progenitors, many of which initially do not express Atoh1, although they eventually contribute to the Atoh1 lineage. Notably, these Lmx1a+ RL cells do not contribute to the full spectrum of Atoh1 RL derivatives. Instead they predominantly produce granule cells that exit the RL during late embryogenesis and occupy the posterior vermis. Lmx1a+ RL cells also may produce UBC. However, because Lmx1a is expressed in UBC after their exit from the RL, we cannot address whether UBC originate from Lmx1a+ or Lmx1a− cells in the RL using our Lmx1a-Cre fate-mapping system. Nonetheless, our data strongly suggest that the RL is not a homogeneous population but rather represents a heterogeneous mixture of progenitors with different developmental potentials. Further, our data show that Lmx1a is not just a marker of a subset of progenitors within the RL. Lmx1a is required for proper development of the Lmx1a+ RL population, for maintenance of the entire RL, and for normal cerebellar morphogenesis.

Using Lmx1a-Cre/ROSA fate mapping, we showed that in dreher embryos, granule cells originating from Lmx1a+ progenitors precociously exit the RL and overmigrate into the anterior vermis. We could recapitulate the premature exit of Lmx1a+ cells from the RL in vitro using explants in which wild-type cerebellar anlage was cocultured with dreher RL. These experiments suggest that Lmx1a acts intrinsically in the RL to prevent the premature exit of Lmx1a+ cells. In the absence of Lmx1a function, many Lmx1a+ cells in the RL ectopically express Atoh1, the gene whose activation leads to rapid migration of cells from the RL into the cerebellum (17). Thus, we posit that Lmx1a prevents precocious migration of progenitors from the early RL by repressing Atoh1, although it is not clear if Lmx1a inhibits Atoh1 expression directly or indirectly. We also acknowledge that although our RL explant culture experiments suggest that Lmx1a acts intrinsically in the RL, the granule cell overmigration defect in dreher embryos may not be mediated exclusively by molecular abnormalities in the RL. For example, RP signaling, RP/RL boundary formation, and/or guidance cues that specifically restrict anterior migration of granule cells also may be affected in dreher mice.

The precocious exit of Lmx1a+ progenitors from the RL was associated with dramatic morphological abnormalities in dreher RL and cerebellum. Although the RL was not grossly affected in dreher embryos at e13.75, its size gradually decreased as development proceeded, and it disappeared by e18.0. It has been shown previously using temporal-specific fate mapping that the early (e13.5) RL gives rise to granule cells of the anterior vermis, whereas the late (e15.5–e18.5) embryonic RL generates granule cells of the posterior vermis (17). Consistent with the premature regression of the RL in dreher embryos, we observed predominant posterior vermis hypoplasia in adult dreher mice. We conclude, therefore, that Lmx1a is required for the maintenance of the entire RL and proper generation of the posterior vermis. Interestingly, in our explants, where wild-type cerebellar anlage was cocultured with dreher RL, we also observed premature regression of dreher RL. Analysis of proliferation and apoptosis revealed no significant differences between wild-type and dreher RL in these explants. This finding suggests that precocious migration of Lmx1a+ cells may be a major cause of the early regression of dreher RL, a pathology that likely underlies posterior vermis hypoplasia in adult dreher mice.

Notably, posterior vermis hypoplasia is a very common feature of most human cerebellar malformations including Dandy-Walker malformation (27). Our dreher mutant mouse data raise the possibility that RL abnormalities may underlie some forms of human congenital cerebellar malformation, providing a conceptual framework within which to assess candidate disease genes.

Lmx1a and Cell-Fate Decisions in the Telencephalic Cortical hem.

The cerebellar RL is not the only germinal zone in the dorsal brain requiring Lmx1a function for normal neurogenesis. Lmx1a also is critical for proper neurogenesis in the CH, a major source of Cajal-Retzius neurons in the developing telencephalon. The consequences of loss of Lmx1a in the CH, however, are not identical to those in the cerebellar RL. In the cerebellar RL, loss of Lmx1a activity causes Lmx1a+ cells to exit the RL precociously and to overmigrate into the anterior vermis. These cells, however, still maintain their granule cell identity. In the telencephalon, in the absence of Lmx1a, CH progenitors adopt hippocampal fates instead of producing Cajal-Retzuis cells. This phenotype seems to be more fundamental than the anterior shift in the cerebellum, because it involves a fate alteration into a different cell type rather than a positional alteration without changing cell-type identity.

Interestingly, in contrast to the cerebellar RL, in the telencephalic CH, Lmx1a-dependent cell-fate decisions cannot be mediated by Atoh1, because this gene is not expressed in the telencephalon. Instead, our data indicate that changes in expression of the hippocampal selector gene Lhx2 (which is not expressed in cerebellar granule cells) may, at least partially, explain the dreher telencephalic phenotype. Therefore, although Lmx1a regulates cell-fate decisions in both these germinal zones, the mechanisms of action at each axial level may diverge. A comprehensive evaluation of downstream targets of Lmx1a and its interacting proteins will be important for understanding the nature of its activity in each developmental context.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

To fate map Lmx1a-expressing progenitors, we generated an Lmx1a-cre BAC transgenic line. More details are given in SI Materials and Methods. Other mouse lines used are found in SI Materials and Methods.

Tissue Analysis and Organotypic Slice Cocultures.

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization were performed as described (18). Explant culture experiments were performed as described (19). More details are given in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Zoghbi, M. Rose (both Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX), S. Dymecki (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), M. German (University of California, San Francisco CA), T. Glaser (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), Y. Sasai (RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe, Japan), R. Hevner, R. Daza (both Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA), and T. Jessell (Columbia University, New York, NY) for providing reagents, and M. Blank, P. Wakenight, and E. Steshina for valuable comments. This work was supported by Grant P30 HD054275 from the Joseph P. Kennedy Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Center, Grant P30 CA014599 from the Cancer Center, and Grants T32GM07179 (to A.G.L.) and RO1 NS044262 (to K.J.M.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.0910786107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Briscoe J, Ericson J. Specification of neuronal fates in the ventral neural tube. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helms AW, Johnson JE. Specification of dorsal spinal cord interneurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:42–49. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hébert JM, Fishell G. The genetics of early telencephalon patterning: Some assembly required. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:678–685. doi: 10.1038/nrn2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landsberg RL, et al. Hindbrain rhombic lip is comprised of discrete progenitor cell populations allocated by Pax6. Neuron. 2005;48:933–947. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chizhikov VV, et al. The roof plate regulates cerebellar cell-type specification and proliferation. Development. 2006;133:2793–2804. doi: 10.1242/dev.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millen KJ, Gleeson JG. Cerebellar development and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldowitz D, Hamre K. The cells and molecules that make a cerebellum. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:375–382. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang VY, Zoghbi HY. Genetic regulation of cerebellar development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:484–491. doi: 10.1038/35081558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wingate RJ, Hatten ME. The role of the rhombic lip in avian cerebellum development. Development. 1999;126:4395–4404. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez CI, Dymecki SM. Origin of the precerebellar system. Neuron. 2000;27:475–486. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson LJ, Wingate RJ. Temporal identity transition in the avian cerebellar rhombic lip. Dev Biol. 2006;297:508–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink AJ, et al. Development of the deep cerebellar nuclei: Transcription factors and cell migration from the rhombic lip. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3066–3076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5203-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter NL, Dymecki SM. Molecularly and temporally separable lineages form the hindbrain roof plate and contribute differentially to the choroid plexus. Development. 2007;134:3449–3460. doi: 10.1242/dev.003095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wingate R. Math-Map(ic)s. Neuron. 2005;48:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hevner RF, Hodge RD, Daza RA, Englund C. Transcription factors in glutamatergic neurogenesis: Conserved programs in neocortex, cerebellum, and adult hippocampus. Neurosci Res. 2006;55:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose MF, Ahmad KA, Thaller C, Zoghbi HY. Excitatory neurons of the proprioceptive, interoceptive, and arousal hindbrain networks share a developmental requirement for Math1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22462–22467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911579106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machold R, Fishell G. Math1 is expressed in temporally discrete pools of cerebellar rhombic-lip neural progenitors. Neuron. 2005;48:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang VY, Rose MF, Zoghbi HY. Math1 expression redefines the rhombic lip derivatives and reveals novel lineages within the brainstem and cerebellum. Neuron. 2005;48:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Englund C, et al. Unipolar brush cells of the cerebellum are produced in the rhombic lip and migrate through developing white matter. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9184–9195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1610-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millonig JH, Millen KJ, Hatten ME. The mouse Dreher gene Lmx1a controls formation of the roof plate in the vertebrate CNS. Nature. 2000;403:764–769. doi: 10.1038/35001573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chizhikov VV, Millen KJ. Control of roof plate formation by Lmx1a in the developing spinal cord. Development. 2004;131:2693–2705. doi: 10.1242/dev.01139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersson E, et al. Identification of intrinsic determinants of midbrain dopamine neurons. Cell. 2006;124:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KJ, Dietrich P, Jessell TM. Genetic ablation reveals that the roof plate is essential for dorsal interneuron specification. Nature. 2000;403:734–740. doi: 10.1038/35001507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Currle DS, Cheng X, Hsu CM, Monuki ES. Direct and indirect roles of CNS dorsal midline cells in choroid plexus epithelia formation. Development. 2005;132:3549–3559. doi: 10.1242/dev.01915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangale VS, et al. Lhx2 selector activity specifies cortical identity and suppresses hippocampal organizer fate. Science. 2008;319:304–309. doi: 10.1126/science.1151695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida M, Assimacopoulos S, Jones KR, Grove EA. Massive loss of Cajal-Retzius cells does not disrupt neocortical layer order. Development. 2006;133:537–545. doi: 10.1242/dev.02209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barkovich AJ, Kjos BO, Norman D, Edwards MS. Revised classification of posterior fossa cysts and cystlike malformations based on the results of multiplanar MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:1289–1300. doi: 10.2214/ajr.153.6.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.