Abstract

Ultrafast lasers are versatile tools used in many scientific areas, from welding to eye surgery. They are also used to coherently manipulate light–matter interactions such as chemical reactions, but so far control experiments have concentrated on cleavage or rearrangement of existing molecular bonds. Here we demonstrate the synthesis of several molecular species starting from small reactant molecules in laser-induced catalytic surface reactions, and even the increase of the relative reaction efficiency by feedback-optimized laser pulses. We show that the control mechanism is nontrivial and sensitive to the relative proportion of the reactants. The control experiments open up a pathway towards photocatalysis and are relevant for research in physics, chemistry, and biology where light-induced bond formation is important.

Keywords: femtochemistry, surface science

Ever since their invention, lasers were considered the ideal tool for microscopic control over chemical bonds, and several seminal coherent control approaches have been developed (1–3). A very successful method to this task is femtosecond quantum control, where selectivity over photoinduced reactions is achieved by exploiting the coherence properties and ultrashort time scales of femtosecond laser radiation (4–6). Combined with learning algorithms processing experimental feedback to adaptively find optimized pulses best suited for solving the control task (7), chemical reactions can even be controlled without a priori knowledge about the reaction mechanisms. This scheme has been successfully applied to dissociative reactions in the gas phase, first on organometallic compounds (8) and later on many other systems. The method is not limited to gas phase experiments, as fluorescence optimizations of molecules in the liquid phase have shown (9–12). Recently, also more complex control tasks have been realized, like the energy flow in large biomolecules (13) or the quantum yield in a photoisomerization reaction (14–16). Femtosecond lasers have also been introduced to the field of photoassociation from atoms in cold traps, in both theory (17, 18) and first experiments (19, 20). However, the selective laser manipulation of bond-forming reactions starting from small reactant molecules that may furthermore exhibit competing bond-forming reaction channels has not been shown yet.

In this contribution, we present the realization of femtosecond laser-assisted catalytic reactions of carbon monoxide and hydrogen or deuterium at a metal surface and further demonstrate that the relative reaction efficiency can be increased by the benefits of femtosecond laser pulses tailored especially for a desired reaction outcome. These experiments represent a first step and a reaction path toward laser-induced catalysis of molecular systems.

Femtosecond laser sources have been employed by laser scientists to explore processes on metal surfaces as soon as they were available. Other types of lasers have been used earlier for this purpose, but starting from the first demonstration of intact desorption of NO molecules from a Pd(111) single crystal induced by femtosecond laser pulses (21), a complete field of ultrafast laser spectroscopy on metal surfaces has emerged among the diversity of surface chemistry techniques (22, 23). Already in early time-resolved experiments (24–26) the unique reaction pathways accessible by the short pulses and the corresponding nonequilibrium excitation of the substrate’s electronic system became apparent and revealed that femtosecond laser desorption is not only because of a phonon-assisted heating effect.

Besides desorption, nuclear wave-packet dynamics of adsorbed molecules could be manipulated (27, 28) by femtosecond lasers, and also a few chemical reactions could be induced. The most prominent among them is the oxidation of carbon monoxide in the presence of oxygen on various surfaces (29, 30). The pioneering work by Ertl and coworkers (30) beautifully revealed the underlying reaction mechanism via hot substrate electrons, a mechanism that also accounts for the recombinative desorption of hydrogen under femtosecond laser irradiation, which clearly differs from thermal excitation (31). However, only very few surface reactions could be observed or assisted by femtosecond lasers, whereas complex catalytic reactions have been completely inaccessible up to now.

We have chosen to explore the reaction of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, coadsorbed on a Pd(100) single crystal surface. When adsorbed on Pd(100), CO does not decompose in the first layer and adsorbs bridge-bonded with the C atom binding to the metal. If the molecular bond is broken [e.g., by electron bombardment (32)], the remaining C atoms can stay on the surface as bulk carbon, which lowers the adsorption energy for further CO adsorption (33). H2 already adsorbs dissociatively at very low coverages and subsequently penetrates into the bulk where it is dissolved (34). Because the maxima for thermal desorption of hydrogen and CO are 360 (34) and 490 K (33), respectively, experiments presented in this work have been performed at 290 K, so that adsorbed species should stick well to the surface and their mobility be still quite high. Recently, coadsorption of carbon monoxide and hydrogen on Pd(111) over a wide pressure range (35) revealed that high-pressure CO structures are identical to high-coverage structures in ultrahigh vacuum, but, despite diverse gas amounts and compositions, no reaction product was observed (35), presumably because of the high energy barriers. A femtosecond laser pulse can provide this energy, whereas specially shaped pulses can steer the outcome into a desired reaction channel.

Experimental Setup

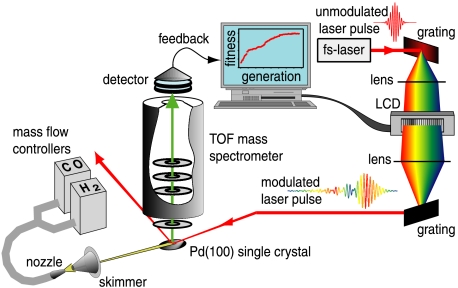

Our experiments are conducted with the setup displayed in Fig. 1. A femtosecond laser system delivers pulses that are phase-modulated in a LCD pulse shaper and then focused onto a metal single crystal surface in a TOF-MS. Ions produced by the laser are detected in the TOF-MS, which is connected to a computer with a learning algorithm. All presented experiments are performed at room temperature and under high vacuum conditions. A more detailed description is given in Materials and Methods.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup. The laser pulses are modulated in a LCD pulse shaper and then focused onto a Pd(100) single crystal surface located in the interaction region of a TOF-MS. The gases are dosed with mass flow controllers and effusively stream via a nozzle and a skimmer onto the surface. The data are directly processed by a computer containing an evolutionary algorithm.

Results

Experiments with Unshaped Pulses.

When the laser beam does not hit the surface, no ions are detected at all. As soon as H2 is streamed onto the laser-irradiated surface, three huge peaks appear in the ion spectrum, attributed to H+,  , and

, and  (Fig. 2, Black Line). The triatomic hydrogen molecule is unstable in the electronic ground state, but excited and ionized states are long-lived and play an important role in molecular spectroscopy (36–40).

(Fig. 2, Black Line). The triatomic hydrogen molecule is unstable in the electronic ground state, but excited and ionized states are long-lived and play an important role in molecular spectroscopy (36–40).

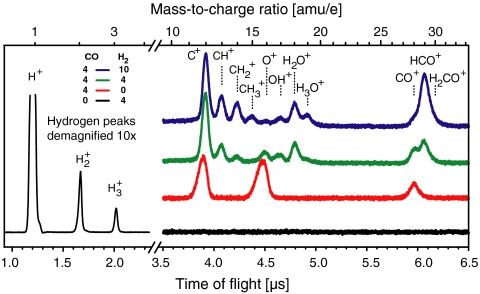

Fig. 2.

Ion spectra (vertically offset for clarity) with different amounts of CO and H2 streamed onto the Pd(100) single crystal. Spectra with H2 only (Black), CO only (Red), an equal mixture of CO and H2 (Green), and an excess of H2 (Blue) are shown. The signal at early times is just shown for the H2-only measurement and is demagnified by a factor of 10 to give an impression of the hydrogen ion peaks. Gas amounts streaming through the nozzle are given in sccm (standard cubic centimeters per minute).

A totally different ion spectrum is detected if only CO enters the chamber. Three peaks arise, which correspond to C+, O+, and CO+, respectively (Fig. 2, Red Line). We do not know the percentage of desorbed CO per laser shot, but the peak heights and the amount of CO introduced into the chamber are directly correlated, and turning off the CO supply results in the disappearance of these peaks.

Additional ion peaks appear when a mixture of CO and H2 is streamed onto the surface. Not only the peaks of the respective single mass spectra change, but also new ion signals arise with rising hydrogen concentration. New peaks at 13, 17, and 29 amu show up first, followed by peaks at 14, 15, 18, and 19 amu (Fig. 2, Green and Blue Lines). These peaks clearly indicate the formation of the ions CH+,  ,

,  , OH+, H2O+, H3O+, and HCO+. An analysis of the latter peak also indicates the formation of H2CO+ (Fig. S1). Varying the temperature of the single crystal from 190 to 390 K did not lead to any further ion peaks. No information can be derived whether methane ions (16 amu) are formed, because they would coincide with O+. The produced hydroxyl, water, and hydronium ion peaks emerge at the expense of the O+ signal and are not because of residual water. By contrast, the production of methylidine, methylene, and methyl cations does not lead to a decrease of the C+ signal, which actually grows with increasing H2 concentration. All ion signals fade away when the gas supply is stopped, with the hydrogen peaks persisting longest.

, OH+, H2O+, H3O+, and HCO+. An analysis of the latter peak also indicates the formation of H2CO+ (Fig. S1). Varying the temperature of the single crystal from 190 to 390 K did not lead to any further ion peaks. No information can be derived whether methane ions (16 amu) are formed, because they would coincide with O+. The produced hydroxyl, water, and hydronium ion peaks emerge at the expense of the O+ signal and are not because of residual water. By contrast, the production of methylidine, methylene, and methyl cations does not lead to a decrease of the C+ signal, which actually grows with increasing H2 concentration. All ion signals fade away when the gas supply is stopped, with the hydrogen peaks persisting longest.

Single Parameter Variations.

In order to further explore the observed photochemical reactions, selected aspects of the macroscopic experimental conditions have been changed. Hence, additional information about the underlying mechanisms and the role of the reactant molecules, the metal surface, and the laser characteristics is obtained.

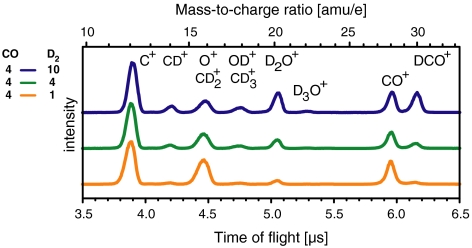

The assignment of the observed product ions is verified by replacing H2 with D2 (Fig. 3). The ion peaks are separated by 2 amu, so that, e.g., the heavy water ion D2O+ appears at 20 amu. The relative efficiency of the bond-forming reactions is lower compared to H2 as can, e.g., be seen by the weak D3O+ signal and the absence of D2CO+ even for the strongest D2 excesses employed (Fig. 3, Blue Line). This behavior can be interpreted as an indication for the reduced mobility of the heavier isotope on the surface, and thus reactions in which more than two particles have to be involved occur with much lower probability.

Fig. 3.

Ion spectra (vertically offset for clarity) with different amounts of CO and D2 streamed onto the Pd(100) single crystal. The CO amount is held constant, whereas the D2 amount is varied.

A central question is the role of the surface in the reactions leading to the observed ion spectra. There is multiple evidence for a decisive involvement of the surface, supported by additional experiments done with our setup and by comparison of our results to the literature: First, we observe the triatomic hydrogen molecule, whose neutral electronic ground state is unstable, in contrast to excited and ionized states. A reported mechanism for  formation is the reaction between

formation is the reaction between  and H2 adsorbed on a metal surface (37), providing a first indication of a surface reaction. Second, the observed C+ increase (which may be because of bulk carbon) under hydrogen supply is comparable to observations by Denzler et al. (31), who disclosed that laser desorption of deuterium from a ruthenium surface is enhanced in the presence of the lighter adsorbate hydrogen. In our case, no deuterium is present, but the carbon monoxide should adsorb with the carbon binding to the surface. The behavior of the C+ signal resembles the situation of D2 desorption in Denzler’s experiment, with the difference that the loosening of the carbon instead of the deuterium adsorption is facilitated by additional hydrogen. Whereas this may indicate a contribution of hydrogen dissociatively absorbed beneath the surface (as do experiments with a platinum crystal; see Fig. S2), the rise of product ions with increasing hydrogen amounts suggests the involvement of hydrogen from the surface. Third, when we replace carbon monoxide by carbon dioxide, no CO2-related ions are observed for all provided amounts of CO2 and all applied laser intensities, indicating that CO2 does not adsorb at all on the Pd surface at room temperature or at least not in such a way that it could be detected analogously to CO. Hence, this reflects the importance of the surface and the adsorption process in the chemical reactions observed with CO. Fourth, when streaming CO and H2 on a Pt(100) single crystal surface, methylidine, hydroxyl, and water ions are formed, but very inefficiently. An excess of H2 leads to a shrinking of all CO-related peaks, in contrast to experiments with the Pd surface, disclosing that the surface material is essential for the initiated catalytic reactions (Fig. S2). Fifth, changing the linear polarization of the laser, performed because signals in laser surface spectroscopy are often polarization-sensitive (22), leads to a strong signal variation over two orders of magnitude, evidencing a directional dependence of the interaction of the light and the adsorbate that is predetermined by the surface (Fig. S3). However, tools for in-detail analysis of the adsorbate’s structure were not available in our experiments; therefore, the CO and hydrogen coverage rates and densities in the vicinity of the surface and also the relative distances of reaction partners on the surface could not be determined. These parameters may significantly contribute to identify the underlying reaction mechanism and should be clarified in future studies.

and H2 adsorbed on a metal surface (37), providing a first indication of a surface reaction. Second, the observed C+ increase (which may be because of bulk carbon) under hydrogen supply is comparable to observations by Denzler et al. (31), who disclosed that laser desorption of deuterium from a ruthenium surface is enhanced in the presence of the lighter adsorbate hydrogen. In our case, no deuterium is present, but the carbon monoxide should adsorb with the carbon binding to the surface. The behavior of the C+ signal resembles the situation of D2 desorption in Denzler’s experiment, with the difference that the loosening of the carbon instead of the deuterium adsorption is facilitated by additional hydrogen. Whereas this may indicate a contribution of hydrogen dissociatively absorbed beneath the surface (as do experiments with a platinum crystal; see Fig. S2), the rise of product ions with increasing hydrogen amounts suggests the involvement of hydrogen from the surface. Third, when we replace carbon monoxide by carbon dioxide, no CO2-related ions are observed for all provided amounts of CO2 and all applied laser intensities, indicating that CO2 does not adsorb at all on the Pd surface at room temperature or at least not in such a way that it could be detected analogously to CO. Hence, this reflects the importance of the surface and the adsorption process in the chemical reactions observed with CO. Fourth, when streaming CO and H2 on a Pt(100) single crystal surface, methylidine, hydroxyl, and water ions are formed, but very inefficiently. An excess of H2 leads to a shrinking of all CO-related peaks, in contrast to experiments with the Pd surface, disclosing that the surface material is essential for the initiated catalytic reactions (Fig. S2). Fifth, changing the linear polarization of the laser, performed because signals in laser surface spectroscopy are often polarization-sensitive (22), leads to a strong signal variation over two orders of magnitude, evidencing a directional dependence of the interaction of the light and the adsorbate that is predetermined by the surface (Fig. S3). However, tools for in-detail analysis of the adsorbate’s structure were not available in our experiments; therefore, the CO and hydrogen coverage rates and densities in the vicinity of the surface and also the relative distances of reaction partners on the surface could not be determined. These parameters may significantly contribute to identify the underlying reaction mechanism and should be clarified in future studies.

To further investigate the observed reactions, pump-probe experiments with two identical femtosecond laser pulses are performed (Fig. S4). The ratio of the peaks does not change drastically for different pump-probe delays, and the transient ion signals resemble the cross-correlations of the two pulses—i.e., exhibit sub-200-fs dynamics. The reaction mechanism hence is not a phonon-mediated heating process (lasting typically tens of picoseconds), but possibly involves electronic excitations of the adsorbate, analogous to the laser-induced oxidation of CO that is because of laser-generated hot substrate electrons, giving rise to subpicosecond reaction dynamics along a new reaction pathway by coupling to the adsorbate (30). However, our experiments totally failed with 400-nm laser pulses at comparable fluence and with all possible linear laser polarizations and exhibited an absence of any CO-related ions, an indication that the dominant mechanism may not be hot substrate electrons but rather a resonance-enhanced excitation and fragmentation of adsorbed CO molecules.

Another potential reaction mechanism derives from experiments where a beam of atomic hydrogen is impinged on a surface preadsorbed with alkenes or halogen atoms, leading to bond formation between the hydrogen and the adsorbate, whereas no reaction occurs with preadsorbed hydrogen atoms (41–44). Although we employ molecular rather than atomic hydrogen, the femtosecond laser initiates nonequilibrium conditions and reactive species like  , and possibly also energetic hydrogen atoms, are formed. Following this line, the reaction mechanism might also comprise sequential processes or ion reactions in close vicinity to the surface.

, and possibly also energetic hydrogen atoms, are formed. Following this line, the reaction mechanism might also comprise sequential processes or ion reactions in close vicinity to the surface.

Quantum Control Experiments.

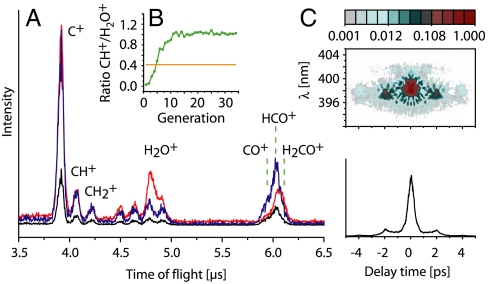

Adaptively optimized femtosecond laser pulses have the potential to selectively manipulate the interactions and/or nonequlibrium conditions necessary for the observed bond formations. To explore whether an evolutionary algorithm finds a pulse shape that increases the production of ions exhibiting a C-H bond, a 1∶1 mixture of CO and H2 is streamed onto the Pd(100) surface. The goal of the experiment is to maximize the amount of CH+ ions versus C+ ions. Enhancement of about 100% compared with the unmodulated laser pulse is achieved with the optimal pulse (Fig. 4). In addition, the  ratio is increased as well by about the same amount. A surprising feature is the strong reduction of H2O+—i.e., a species having an O-H bond, with the optimal pulse, which comprises a pulse sequence with a broad main pulse and a smaller subpulse (Fig. 4C). We have varied the pulse energy and recorded ion spectra with the unmodulated pulse, but neither such a reduction of the H2O+ signal relative to the other peaks nor the increase in the CH+/C+ ratio could be achieved. From the experimental data we conclude that the optimal pulse favors the formation of ions having a C-H bond, whereas H2O+ production is suppressed. The yield of CO+, HCO+, and H2CO+ relative to C+ is also greatly enhanced (Fig. 4A).

ratio is increased as well by about the same amount. A surprising feature is the strong reduction of H2O+—i.e., a species having an O-H bond, with the optimal pulse, which comprises a pulse sequence with a broad main pulse and a smaller subpulse (Fig. 4C). We have varied the pulse energy and recorded ion spectra with the unmodulated pulse, but neither such a reduction of the H2O+ signal relative to the other peaks nor the increase in the CH+/C+ ratio could be achieved. From the experimental data we conclude that the optimal pulse favors the formation of ions having a C-H bond, whereas H2O+ production is suppressed. The yield of CO+, HCO+, and H2CO+ relative to C+ is also greatly enhanced (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

(A) Ion spectra for the maximization of the ratio CH+/C+ with 4 sccm CO and 4 sccm H2, obtained with unmodulated (Red) and optimal pulse (Black). For comparison, the blue curve shows the latter ion spectrum rescaled by a factor such that the C+ peaks for unmodulated and optimal pulse match. (B) The green curve shows the development of the fitness (the average of the ten best individuals per generation), whereas the signal level of the unmodulated pulse is indicated by an orange line. (C) SHG-FROG trace (Top) and autocorrelation (Bottom) of the optimal pulse.

Because water formation has been reduced even though this has not been the goal of the previous optimization, we included the H2O+ yield as a parameter in the fitness function. Another optimization experiment under virtually the same conditions is performed with the chosen control goal being the maximization of the ratio CH+/H2O+. Although performed on another day and with a slightly different starting ratio compared to the CH+/C+ optimization, the control goal has been achieved just as nicely. Fig. 5 shows that the H2O+ peak is reduced by about 50% relative to C+. Whereas the absolute yield for H2O+ initially is larger than for CH+, this ratio is reversed with the optimal pulse. The relative production of CO+ and HCO+ is increased, whereas CH+ and  practically do not change relative to C+. Hence, with the ratio CH+/H2O+ as fitness signal used here, a direct discrimination of a ion species bearing an O-H bond relative to one bearing a C-H bond has been achieved, with the algorithm converging faster than for the CH+/C+ optimization (see Fig. 5B). A replacement of H2 with D2 in the experiments has led to successful optimizations with similar results.

practically do not change relative to C+. Hence, with the ratio CH+/H2O+ as fitness signal used here, a direct discrimination of a ion species bearing an O-H bond relative to one bearing a C-H bond has been achieved, with the algorithm converging faster than for the CH+/C+ optimization (see Fig. 5B). A replacement of H2 with D2 in the experiments has led to successful optimizations with similar results.

Fig. 5.

(A) Ion spectra for the maximization of the ratio CH+/H2O+ with 4 sccm CO and 4 sccm H2, obtained with unmodulated (Red) and optimal pulse (Black). For comparison, the blue curve shows the latter ion spectrum rescaled by a factor such that the C+ peaks for unmodulated and optimal pulse match. (B) The green curve shows the development of the fitness (the average of the ten best individuals per generation), whereas the signal level of the unmodulated pulse is indicated by an orange line. (C) SHG-FROG trace (Top) and autocorrelation (Bottom) of the optimal pulse.

For both optimizations, the second-harmonic frequency-resolved optical gating (SHG-FROG) traces (Figs. 4C and 5C) show a pulse sequence with a broad main pulse and a smaller subpulse, separated by ≈2 ps. In the pump-probe experiments (Fig. S4), using two identical unmodulated pulses at temporal distances longer than one pulse width has not led to any signal at all. The energy of the incoming laser field was comparable in all the experiments; however, whereas the energy in the pump-probe experiments has been distributed evenly over the two pulses, the relative position and intensity of the substructures of the optimized pulses might make the difference.

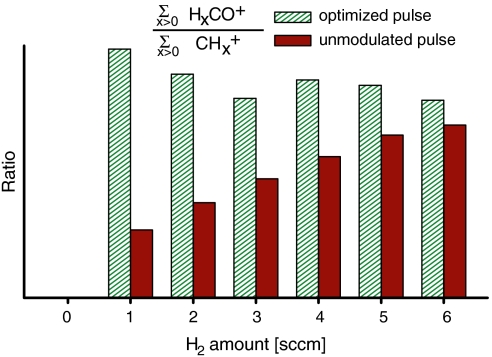

Gas Amount Variation for Optimized Pulses.

The relative proportion of the two gases can be easily changed, allowing an analysis of the optimization effect with respect to the adsorbate composition. A systematic variation substantiates that the optimization is not achieved via control of carbon monoxide dissociation only: As an initial experiment, just CO is employed and the ratio CO+/C+ is maximized. Afterwards, hydrogen is streamed onto the surface. If the amount of H2 is small compared to CO, the optimization effect of an increased ratio CO+/C+ is also transferred to the hydrogenated species (Fig. 6). Yet, a further rise of the H2 concentration leads to modified conditions on the surface, as, e.g., adsorbate arrangement and electronic states change. Hence, the optimization effect goes away when the amount of H2 is increased, and the ratio of hydrogenated ions with the optimal pulse approaches the ratio with an unmodulated pulse (Fig. 6). One can conclude that the best pulse in the absence of H2 is not special anymore if large H2 amounts are applied, proving that the pulse is adapted to the specific conditions during the optimization. This conclusion has also been confirmed by the opposite procedure: Optimal pulses obtained with both gases have no effect on the shape of the mass spectrum anymore if only CO is employed.

Fig. 6.

Variation of H2 concentration after an optimization. After maximization of the ratio CO+/C+ with 4 sccm CO only, H2 is streamed onto the surface. The graph shows the ratio of all species with hydrogenated CO (29–30 amu) to those with hydrogenated C (13–15 amu). The optimization effect fades away with increasing H2 amounts.

Conclusion

The presented experiments demonstrate the feasibility of laser-induced catalytic reactions of carbon monoxide and hydrogen on a palladium single crystal. Several product molecules have been synthesized, among them also species (e.g.,  ) in whose formation at least three of the initial particles are involved. Our results show that the interaction of the surface, its adsorbate, and the femtosecond laser field occurs on an ultrafast subpicosecond time scale, where the dominant mechanism might not be hot substrate electrons but possibly a resonance-enhanced process, and is sensitive to the incident laser polarization.

) in whose formation at least three of the initial particles are involved. Our results show that the interaction of the surface, its adsorbate, and the femtosecond laser field occurs on an ultrafast subpicosecond time scale, where the dominant mechanism might not be hot substrate electrons but possibly a resonance-enhanced process, and is sensitive to the incident laser polarization.

By applying a feedback femtosecond optimal control scheme, these reactions are manipulated and the ratio of different reaction channels is selectively changed. It was shown that the underlying control mechanism is nontrivial and sensitive to the specific conditions on the surface. In contrast to previous quantum control experiments, reaction channels comprising the formation of molecular bonds rather than the cleavage of already existing bonds are controlled, a major advance opening the door toward selective laser-induced molecular catalysis.

Materials and Methods

The setup used in our experiment is outlined in Fig. 1. A titanium-sapphire femtosecond regenerative amplifier delivers laser pulses with a pulse duration of 80 fs and pulse energies of up to 1 mJ at a center wavelength of 800 nm and at a repetition rate of 1 kHz. A LCD pulse shaper with 128 independent pixels in the Fourier plane of a zero dispersion compressor is employed to modify the spectral phase of the laser pulses while leaving the spectrum unchanged (for more detail, see, e.g., ref. 45). A genetic algorithm in combination with a feedback loop is established to optimize the electric field for the desired task (fitness) by direct processing of the experimental data received for a certain pulse shape. Each generation comprises 60 tested pulse shapes; the 10 best ones are used to create the pulses of the next generation by cloning, crossover, and mutation. The pulse shapes can be characterized by SHG-FROG (46), where a spectrally resolved autocorrelation is used to assess the complete electric field of the pulse. The laser beam is focused by a lens with a focal length of 40 cm into the main vacuum chamber onto the single crystal under an angle of roughly 15° to the surface. Only a few percent of the laser energy is employed , and the maximum intensity on the surface is about 1012 W/cm2. Laser intensities are chosen such that the formation of metal ions is negligible. The beam is reflected by the crystal and leaves the vacuum chamber again through another window. The gases H2, D2, and CO have been purchased with purities of at least 99.999%, 99.7%, and 99.997%, respectively, and are used as-is. Mass flow controllers especially calibrated for the gases are employed to dose the amount of gas that is allowed to enter the system. The two gas pipes are combined in front of a nozzle through which the gas mixture enters the collateral vacuum chamber, where it hits a skimmer and results in a gas beam into the main vacuum chamber. The skimmer is the only connection between the two vacuum chambers, and the three elements nozzle, skimmer, and crystal are located along one line. The single crystal [Pd(100) or Pt(100), diameter 10 mm, thickness 1 mm] is mounted with a slight angle of about 5° tilted toward the molecular beam so that the gas not only streaks over the surface but may actually hit it. Perpendicular to the gas beam and almost parallel to the surface normal, there is a TOF mass spectrometer with a system of electrodes to accelerate ions that are produced when the laser beam interacts with the surface and its adsorbates. These ions generate an electric signal on a chevron-stacked microchannel plate assembly after flight times that are directly related to their mass. These signals are recorded either directly via a digital oscilloscope or via a time-to-digital converter after a fast preamplifier. The crystal, mounted on the repeller of the TOF, is set to a voltage of +200 V. Several subsequent grounded electrodes guarantee a field-free drift region, whereas at the detector itself the back and front plates of the microchannel plate assembly are set to -100 and +1,800 V, respectively, followed by a conical anode at 0 V. The whole repeller assembly including the single crystal can be heated, as well as cooled by a cryogenic system. The base pressure in the main chamber, without exposure to the two gases, is 10-6 torr, whereas up to 10-4 torr are reached with the highest gas amounts employed in the experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

H.W. appreciates constant support and encouragement of Prof. Brandstetter and Prof. Iden (BASF). We gratefully acknowledge the group of Prof. Gauss (Univ Mainz), Dr. Wohlleben (BASF), and Prof. Brixner (Univ Würzburg) for stimulating discussions, Dr. Niklaus and Dr. Papastathopoulos for help in the early phase of the project, and the BASF SE for financial support. P.N. acknowledges financial support from the Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina (BMBF-LPDS 2009-6).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.0913607107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rice SA, Zhao M. Optical Control of Molecular Dynamics. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brumer PW, Shapiro M. Principles of the Quantum Control of Molecular Processes. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tannor DJ. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics: A Time-Dependent Perspective. Sausalito, CA: University Science Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumert T, Grosser M, Thalweiser R, Gerber G. Femtosecond time-resolved molecular multiphoton ionization: The Na2 system. Phys Rev Lett. 1991;67:3753–3756. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter ED, Herek JL, Pedersen S, Liu Q, Zewail AH. Femtosecond laser control of a chemical reaction. Nature. 1992;355:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meshulach D, Silberberg Y. Coherent quantum control of two-photon transitions by a femtosecond laser pulse. Nature. 1998;396:239–242. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Judson RS, Rabitz H. Teaching lasers to control molecules. Phys Rev Lett. 1992;68:1500–1503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assion A, et al. Control of chemical reactions by feedback-optimized phase-shaped femtosecond laser pulses. Science. 1998;282:919–922. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bardeen CJ, et al. Feedback quantum control of molecular electronic population transfer. Chem Phys Lett. 1997;280:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brixner T, Damrauer NH, Niklaus P, Gerber G. Photoselective adaptive femtosecond quantum control in the liquid phase. Nature. 2001;414:57–60. doi: 10.1038/35102037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth M, et al. Quantum control of tightly competitive product channels. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102:253001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.253001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuernberger P, Vogt G, Brixner T, Gerber G. Femtosecond quantum control of molecular dynamics in the condensed phase. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:2470–2497. doi: 10.1039/b618760a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herek JL, Wohlleben W, Cogdell RJ, Zeidler D, Motzkus M. Quantum control of energy flow in light harvesting. Nature. 2002;417:533–535. doi: 10.1038/417533a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogt G, Krampert G, Niklaus P, Nuernberger P, Gerber G. Optimal control of photoisomerization. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94:068305. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.068305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietzek B, Brüggemann B, Pascher T, Yartsev A. Mechanisms of molecular response in the optimal control of photoisomerization. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97:258301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.258301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prokhorenko VI, et al. Coherent control of retinal isomerization in bacteriorhodopsin. Science. 2006;313:1257–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.1130747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luc-Koenig E, Kosloff R, Masnou-Seeuws F, Vatasescu M. Photoassociation of cold atoms with chirped laser pulses: Time-dependent calculations and analysis of the adiabatic transfer within a two-state model. Phys Rev A. 2004;70:033414. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poschinger U, et al. Theoretical model for ultracold molecule formation via adaptive feedback control. J Phys B. 2006;39:S1001–S1015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown BL, Dicks AJ, Walmsley IA. Coherent control of ultracold molecule dynamics in a magneto-optical trap by use of chirped femtosecond laser pulses. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:173002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.173002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salzmann W, et al. Coherent control with shaped femtosecond laser pulses applied to ultracold molecules. Phys Rev A. 2006;73:023414. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prybyla JA, Heinz TF, Misewich JA, Loy MMT, Glownia JH. Desorption induced by femtosecond laser pulses. Phys Rev Lett. 1990;64:1537–1540. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.64.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai H-L, Ho W, editors. Laser Spectroscopy and Photochemistry on Metal Surfaces. Singapore: World Scientific; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somorjai G. Introduction to Surface Chemistry and Catalysis. New York: Wiley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budde F, et al. Femtosecond time-resolved measurement of desorption. Phys Rev Lett. 1991;66:3024–3027. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.66.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prybyla JA, Tom HWK, Aumiller GD. Femtosecond time-resolved surface reaction: desorption of CO from Cu(111) in < 325 fsec. Phys Rev Lett. 1992;68:503–506. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao F-J, Busch DG, Cohen D, Gomes da Costa D, Ho W. Femtosecond laser desorption of molecularly adsorbed oxygen from Pt(111) Phys Rev Lett. 1993;71:2094–2097. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petek H, Ogawa S. Surface femtochemistry: Observation and quantum control of frustrated desorption of alkali atoms from noble metals. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2002;53:507–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.53.090701.100226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto Y, Watanabe K. Coherent vibrations of adsorbates induced by femtosecond laser excitation. Chem Rev. 2006;106:4234–4260. doi: 10.1021/cr050165w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao F-J, Busch DG, Gomes da Costa D, Ho W. Femtosecond versus nanosecond surface photochemistry: O2 + CO on Pt(111) at 80 K. Phys Rev Lett. 1993;70:4098–4101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonn M, et al. Phonon- versus electron-mediated desorption and oxidation of CO on Ru(0001) Science. 1999;285:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denzler DN, Frischkorn C, Hess C, Wolf M, Ertl G. Electronic excitation and dynamic promotion of a surface reaction. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;91:226102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.226102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tracy JC, Palmberg PW. Structural influences on adsorbate binding energy. I. Carbon monoxide on (100) palladium. J Chem Phys. 1969;51:4852–4862. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behm RJ, Christmann K, Ertl G, Van Hove MA. Adsorption of CO on Pd(100) J Chem Phys. 1980;73:2984–2995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Behm RJ, Christmann K, Ertl G. Adsorption of hydrogen on Pd(100) Surf Sci. 1980;99:320–340. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morkel M, Rupprechter G, Freund H-J. Ultrahigh vacuum and high-pressure coadsorption of CO and H2 on Pd(111): A combined SFG, TDS and LEED study. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:10853–10866. [Google Scholar]

-

36.Weingartshofer A, Clarke EM. Cross sections for the ion-molecule reaction

as a function of the vibration state of the

as a function of the vibration state of the  ion. Phys Rev Lett. 1964;12:591–592. [Google Scholar]

ion. Phys Rev Lett. 1964;12:591–592. [Google Scholar] - 37.Papp N, Kerwin L. Some new Aston bands in hydrogen. Phys Rev Lett. 1969;22:1343–1346. [Google Scholar]

-

38.Anderson SL, Houle FA, Gerlich D, Lee YT. The effect of vibration and translational energy on the reaction dynamics of the

system. J Chem Phys. 1981;75:2153–2162. [Google Scholar]

system. J Chem Phys. 1981;75:2153–2162. [Google Scholar] - 39.Figger H, et al. Spectroscopy of triatomic hydrogen molecules in a beam. Phys Rev Lett. 1984;52:906–909. [Google Scholar]

-

40.McCall BJ, Oka T.

—An ion with many talents. Science. 2000;287:1941–1942. [Google Scholar]

—An ion with many talents. Science. 2000;287:1941–1942. [Google Scholar] - 41.Xi M, Bent BE. Evidence for an Eley-Rideal mechanism in the addition of hydrogen atoms to unsaturated hydrocarbons on Cu(111) J Vac Sci Technol B. 1992;10:2440–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teplyakov AV, Bent BE. Distinguishing direct and quasi-direct mechanisms for an Eley-Rideal gas/surface reaction. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans. 1995;91:3645–3654. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rettner CT, Auerbach DJ. Distinguishing the direct and indirect products of a gas-surface reaction. Science. 1994;263:365–367. doi: 10.1126/science.263.5145.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rettner CT. Reaction of an H-atom beam with Cl/Au(111): Dynamics of concurrent Eley-Rideal and Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanisms. J Chem Phys. 1994;101:1529–1546. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumert T, Brixner T, Seyfried V, Strehle M, Gerber G. Femtosecond pulse shaping by an evolutionary algorithm with feedback. Appl Phys B. 1997;65:779–782. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trebino R. Frequency-Resolved Optical Gating: The Measurement of Ultrashort Pulses. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.