Abstract

AIM: To demonstrate the optimal surgical procedure for gastroesophageal reflux disease.

METHODS: The electronic databases of Medline, Elsevier, Springerlink and Embase over the last 16 years were searched. All clinical trials involved in the outcomes of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF) and laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication (LTF) were identified. The data of assessment in benefits and adverse results of LNF and LTF were extracted and compared using meta-analysis.

RESULTS: We ultimately identified a total of 32 references reporting nine randomized controlled trials, eight prospective cohort trials and 15 retrospective trials. These studies reported a total of 6236 patients, of whom 4252 (68.18%) underwent LNF and 1984 (31.82%) underwent LTF. There were no differences between LNF and LTF in patients’ satisfaction, perioperative complications, postoperative heartburn, reflux recurrence and re-operation. Both LNF and LTF enhanced the function of lower esophageal sphincter and improved esophagitis. The postoperative dysphagia, gas-bloating syndrome, inability to belch and the need for dilatation after LNF were more common than after LTF. Subgroup analyses showed that dysphagia after LNF and LTF was similar in patients with normal esophageal peristalsis (EP), but occurred more frequently in patients with weak EP after LNF than after LTF. Furthermore, patients with normal EP after LNF still had a higher risk of developing dysphagia than did patients with abnormal EP after LTF.

CONCLUSION: Compared with LNF, LTF offers equivalent symptom relief and reduces adverse results.

Keywords: Laparoscopic fundoplication; Nissen, Toupet; Gastroesophageal reflux disease; Anti-reflux surgery; Esophageal peristalsis; Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic acid-peptic disorder characterized by the spontaneous and involuntary retrograde flow of stomach contents into esophagus mainly due to functional defect of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES)[1]. Acid reflux into the esophagus may cause esophagitis, tracheobronchitis, stricture, Barrett’s esophagus and even esophageal cancer, all of which affect a sizeable portion of patients, particularly in the USA and Europe[2-5]. Symptomatic GERD has fundamental effects on the quality-of-life (QOL) of patients. However, the complex pathophysiology of GERD[4] and limitation of the medicine[6] always make it extremely difficult to get a satisfactory efficacy under individual anti-acid medication in the long term.

Surgery is discussed as a very effective treatment for GERD which imparts a mechanical solution[6]. Surgical treatment was initially introduced by Rudolph Nissen[7] in 1956 and subsequently was developed as a safe and effective procedure by Dallemagne in 1991 through a minimal invasive approach[8]. Laparoscopic fundoplication has been established as the “gold standard” in the surgical treatment for GERD because of its immense success. There are two major anti-reflux procedures: 360º total (Nissen) fundoplication and 270º partial (Toupet) fundoplication. The superiority of one over the other is a matter of debate. The supporters of partial fundoplication argue that partial and total wrap construction offer equally effective forms of therapy for GERD[9-11]. To avoid the major postoperative complication, dysphagia, preoperative esophageal motility should be considered, and partial funduplication has the advantage of reducing this complication[12,13]. The proponents of total fundoplication propose that: (1) the 270º wrap provides a weaker anti-reflux barrier, and is therefore insufficient for reflux control[14,15]; (2) the prevalence of postoperative dysphagia after Nissen fundoplication is overestimated; and (3) motility disorders are not correlated with postoperative dysphagia[16], suggesting that the so-called “tailored procedure” should be abandoned[17,18]. Many crucial issues related to the mechanism of GERD, such as whether esophageal dysmotility is a consequence of GERD or just another component (along with LES dysfunction) of a complex foregut motor disease, have not been elucidated[19,20], so the controversy regarding the optimal surgical technique continues[21,22].

Meta-analysis is a powerful tool with an attempt to overcome the problem of reduced statistical power in studies with small sample sizes and to control variations between studies. The goal of surgical treatment for GERD is to provide optimal reflux control while minimizing adverse results. We focused this current systemic review on comparing which procedure was more effective in improving the QOL of patients while producing less adverse results. We attempted to depict a more comprehensive picture of the feature of laparoscopic anti-reflux operation, thus offering guidance for clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

The electronic databases of Medline, ScienceDirect (Elsevier), Springerlink and Embase over the last 16 years from January 1994 to November 2009 were searched by two authors (Shan CX and Zhang W) to identify all clinical trials comparing laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF) with laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication (LTF). A search strategy using disease-specific search terms (e.g. gastroesophageal reflux disease), management-specific terms (e.g. laparoscopic anti-reflux fundoplication) and terms related to surgical procedures (e.g. Nissen, Toupet, partial and total) was adopted. All photocopied abstracts and citations were reviewed. The related articles were used to broaden the searching scope, and references of the articles acquired were also searched.

Selection criteria

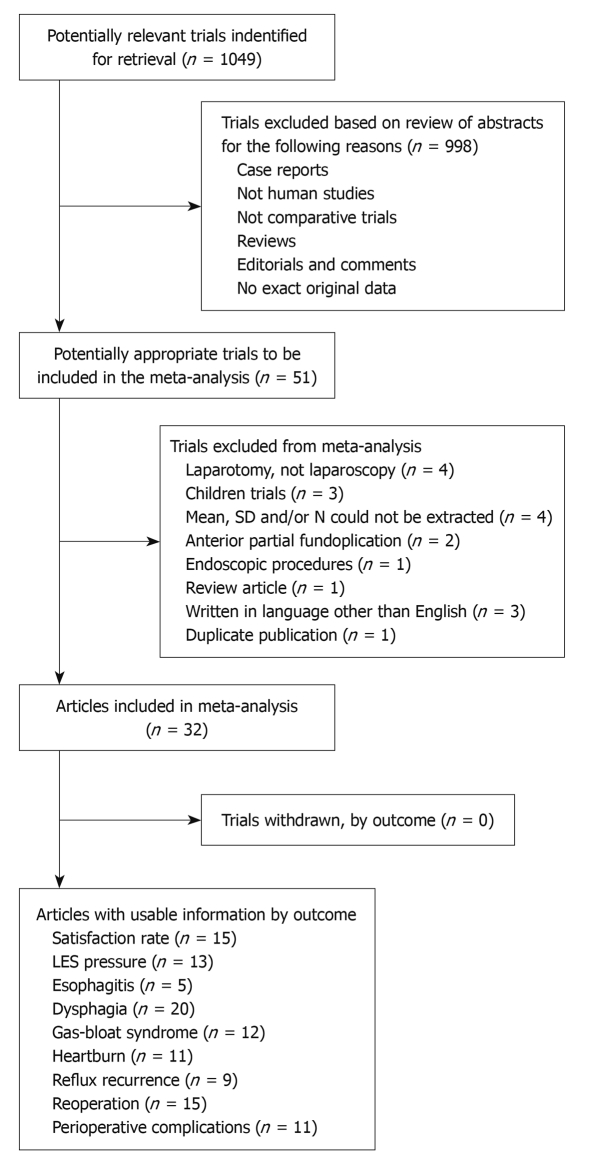

Abstracts or full-text articles were initially screened, and then selected or rejected by the two reviewers (Shan CX and Zhang W) on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria described below. A flow chart representing selection of clinical trials is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow chart showing the progress of trials through the review. LES: Lower esophageal sphincter.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Comparative clinical trials, including randomized and non-randomized controlled trials, involved in the efficacy and adverse results of different types of laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery (LARS); and (2) The exact data of dichotomous-type information and continuous-type information as well as standard deviation should be provided so as to integrate each single weight in each study.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Comparative trials between total and non-posterior partial fundoplication (e.g. total vs anterior partial fundoplication); (2) Fundoplications were carried out with laparotomy; (3) Trials involving children or patients younger than 16 years; and (4) Studies published repeatedly by different journals.

Data extraction

The two reviewers independently extracted details from selected studies which comprised (1) information and quality of the research: first author, year of publication, comparative design, sample capacity, follow-up duration; and (2) outcome analysis, including beneficial and adverse results. The specific rules of data extraction were listed below.

First, the assessment data of repeated trials published in different journals at different phases was extracted based on the latest article. For example, the results in the studies of Strate et al[16], Fibbe et al[23] and Zornig et al[24] were highly homologous, containing identical study objects and design protocol. Thus, the source of data extraction was focused on the latest citation of Zornig et al[24].

Second, the assessment data of trials containing multiple groups were initially divided into single groups, and then extracted individually. For example, the research of Mickevicius et al[22] included two subgroups of LARS with a 1.5-cm wrap fundoplication and 3.0-cm wrap. We split it into two independent trials according to the wrap length.

And third, the evaluation indices of surgical efficacy and incidence of postoperative morbidities were subject to the final updates based on long-term follow-up results. For example, Chrysos et al[25] reported the 3- and 12-mo incidences of postoperative dysphagia in their article. We ultimately extracted the information on the 12-mo incidence of dysphagia after LARS and integrated it into the total meta-analysis.

Statistical analysis

All individual outcomes were integrated with the meta-analysis software: Review Manager Software 5.0 (Cochrane Collaborative, Oxford, England). Results were analyzed with the random-effect method if significant heterogeneity (P < 0.05 was used to define statistically significant heterogeneity) was detected among studies. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model was adopted. The odds ratio (OR) and the weighted mean difference were calculated for dichotomous data and continuous data, respectively. In addition, subgroup analyses were done to estimate if the results of postoperative dysphagia would change after LARS with respect to preoperative esophageal motility (EM). Thus, three subgroups were established. Subgroup 1: all patients underwent LNF or LTF and had normal esophageal peristalsis (EP); subgroup 2: all patients underwent LNF or LTF and had abnormal EP; and subgroup 3: LNF for patients with normal EP vs LTF for patients with abnormal EP.

RESULTS

Identification and characteristics of studies and patients

We ultimately identified 32 references reporting 29 independent controlled studies published between January 1994 and November 2009. Nine randomized controlled trials[10,16,21-27], eight prospective cohort trials[11,17,28-33] and 15 retrospective trials[9,12,20,33-45] met the selection criteria reporting 6236 patients, of whom 4252 (68.18%) underwent LNF and 1984 (31.82%) underwent LTF. Twenty studies provided the sex and 11 trials provided the age of included patients. The percentage of males varied from 39.39% to 70.13% in the LNF group, and from 39.53% to 66.67% in the LTF group. The mean age ranged from 45.2 to 59.2 years in the LNF group and from 44.2 to 61.7 years in the LTF group. The details of these studies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

LNF and LTF in treatment of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease

| Data source | Design | PF (º) | Sample capacity (LNF/LTF) | Group or subg. depend on EM | Follow-up (mo) | Level of evidence |

| Mickevicius et al[22], 2008 | RCT | 200-270 | 76/77 | No detail | 12 | 1b Level A |

| Fibbe et al[23], 2001 | ||||||

| Zornig et al[24], 2002 | RCT | 270 | 100/100 | More subgroups | 24 | 1b Level A |

| Strate et al[16], 2008 | ||||||

| Chrysos et al[25], 2003 | RCT | 270 | 14/19 | Both abnormal | 12 | 2b Level B |

| Guérin et al[26], 2007 | RCT | 270 | 77/63 | Normal-Nissen/Abnormal-Toupet | 36 | 1b Level A |

| Laws et al[10], 1997 | RCT | 200 | 23/16 | Both normal | 27.2 | 2b Level B |

| Shaw et al[27], 2010 | RCT | 270 | 50/50 | No detail | > 55 | 1b Level A |

| Booth et al[21], 2008 | RCT | 270 | 64/63 | No detail | 12 | 1b Level A |

| Coster et al[28], 1997 | PCT | No detail | 125/101 | No detail | 12 | 2b Level B |

| Granderath et al[29], 2007 | PCT | 270 | 28/28 | Both normal | 3 | 3b Level B |

| Wykypiel et al[30], 2008 | PCT | 300 | 20/20 | Normal-Nissen/Abnormal-Toupet | 6 | 3b Level B |

| Hunter et al[31], 1996 | PCT | 180-300 | 101/83 | Both normal | 3 | 3b Level B |

| Bessell et al[17], 2000 | PCT | 200-270 | 761/85 | More subgroups | 12 | 2b Level B |

| Radajewski et al[32], 2009 | PCT | No detail | 51/43 | No detail | 12 | 2b Level B |

| Kamolz et al[33], 2000 | PCT | No detail | 107/68 | No detail | 60 | 2b Level B |

| Kamolz et al[11], 2002 | ||||||

| Sgromo et al[34], 2008 | RT | No detail | 150/116 | No detail | 72 | 2b Level B |

| Erenoğlu et al[35], 2003 | RT | 270 | 118/26 | Normal-Nissen/Abnormal-Toupet | 27.5 | 2b Level B |

| Herbella et al[20], 2007 | RT | 240 | 55/16 | More subgroups | 16 | 3b Level B |

| Wetscher et al[12], 1997 | RT | No detail | 17/32 | Normal-Nissen/Abnormal-Toupet | 15 | 3b Level B |

| Fernando et al[36], 2002 | RT | 270 | 163/43 | No detail | 19.7 | 2b Level B |

| Wykypiel et al[37], 2005 | RT | 300 | 77/132 | Normal-Nissen/Abnormal-Toupet | 52 | 2b Level B |

| McKernan et al[38], 1994 | RT | 180-200 | 14/14 | No detail | > 3.4 | 3b Level B |

| Fein et al[45], 2008 | RT | No detail | 88/10 | Normal-Nissen/Abnormal-Toupet | 120 | 2b Level B |

| Patti et al[39], 2004 | RT | 240 | 216/141 | More subgroups | > 23 | 2b Level B |

| Zügel et al[9], 2002 | RT | 270 | 40/122 | No detail | 19 | 2b Level B |

| Pessaux et al[40], 2000 | RT | 180 | 1078/392 | No detail | 24 | 2b Level B |

| Bell et al[41], 1996 | RT | 180 | 11/11 | No detail | 13 | 4 Level C |

| Lund et al[42], 1997 | RT | 270 | 16/46 | Both abnormal | 6 | 3b Level B |

| Farrell et al[43], 2000 | RT | 270 | 293/52 | More subgroups | 12 | 3b Level B |

| Heider et al[44], 2003 | RT | 270 | 15/4 | Both abnormal | 29.5 | 4 Level C |

LNF: Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication; LTF: Laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication; PF: Circumferential degrees of the partial wrap; Subg.: Subgroup; EM: Esophageal motility; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; PCT: Prospective controlled trial; RT: Retrospective trial.

Subjective assessment: Satisfaction rate

Fifteen studies assessed patient satisfaction as the major efficacy of LARS. In addition, patient satisfaction with the outcome of surgery was always expressed by Visick scores evaluating QOL. After follow-up, each single research suggested that > 90% patients were satisfied with postoperative outcomes after LNF or LTF, and 91.78% (1674/1824) of patients in the LNF group and 91.33% (938/1027) in the LTF group reported excellent or good results after LARS. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR 0.96, 95% CI: 0.72-1.28, P = 0.77).

Objective evaluation

LES pressure: The change in LES pressure after LARS was investigated in 13 trials. The mean preoperative LES pressure was 3.1-12.8 mmHg in the LNF group, and about 2.3-13.6 mmHg in the LTF group, and increased significantly to 10.3-26 mmHg after LNF and 11-18 mmHg after LTF, respectively. Moreover, 360º total fundoplication could form a relatively stronger anti-reflux barrier than 270º partial funduplication because the amplitude of LES pressure increase was significantly higher after LNF than after LTF (OR 2.76, 95% CI: 1.57-3.95, P < 0.05).

Esophagitis: Five authors outlined the improvement of preoperative esophagitis after LARS by endoscopy. Esophagitis severity was graded according to the Savary-Miller classification in most studies. Remission of moderate-to-severe esophagitis was observed by endoscopic re-examination after anti-reflux procedures; there was a reduction in case number from 87/210 to 12/191 in the Nissen group, and from 99/218 to 17/197 in the LTF group. There was no significant difference in remission rate between the two groups (6.28% vs 8.63%, OR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.59-1.33, P = 0.42).

Adverse results: Perioperative complications

Eleven studies reported the surgical complications in 1622 patients with LNF and 836 patients with LTF. Both techniques entailed a low (but definite) risk of surgical morbidity which occurred in 1.30%[26]-14.28%[25] of the population after Nissen fundoplication and in 2.46%[9]-15.63%[12] of the population after Toupet fundoplication. Lacerations of the gastric fundus and spleen, bleeding from the spleen or short gastric blood vessels and pneumothorax were the main disease categories. However, surgical mortality was also a natural sporadic event. Only two patients died: one on the 15th day after LNF due to secondary peritonitis from necrosis of the wrap[40], and the other died of esophageal perforation and mediastinitis[22]. The cumulative prevalence of perioperative complications after LNF and LTF was 4.01% and 5.14%, respectively, with no significant difference between the groups (4.01% vs 5.14%, OR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.47-1.12, P = 0.15).

Postoperative symptoms

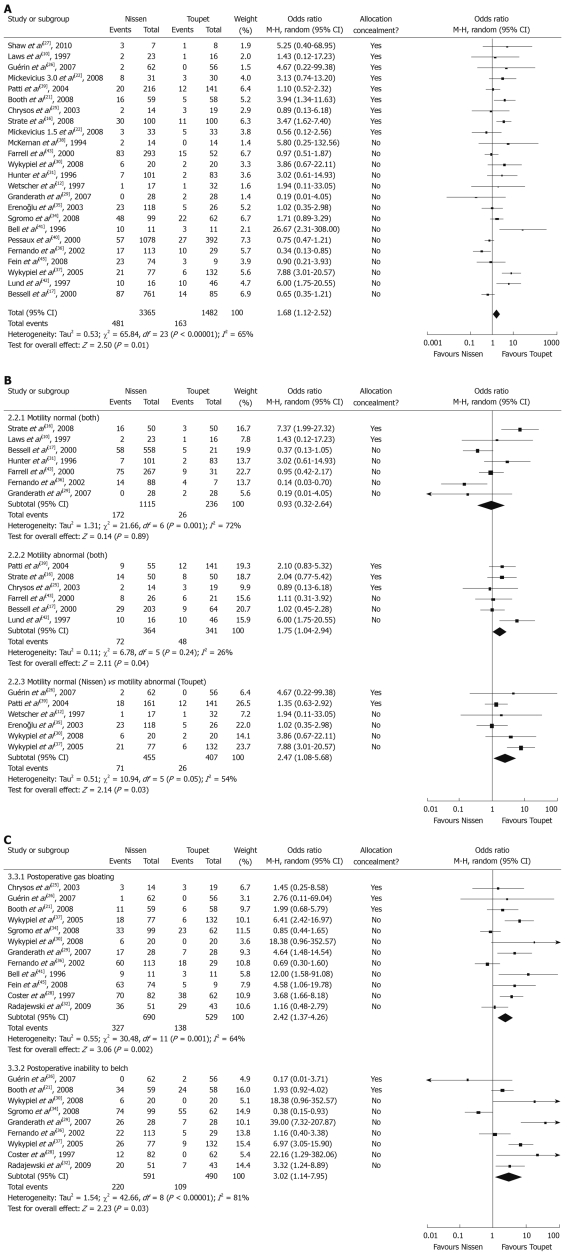

Dysphagia and need for bougie dilatation: Twenty-four studies assessed the outcome of dysphagia after LARS. Various questionnaires were used to define dysphagia severity, ranging from no symptoms to very severe episodes at the end of follow-up. The overall prevalence of dysphagia after LNF was significantly higher than after LTF (14.29% vs 11.00%, OR 1.68, 95% CI: 1.12-2.52, P = 0.01) (Figure 2A). A similar result was also obtained if only patients with moderate-to-severe dysphagia were included (12.30% vs 2.74%, OR 3.11, 95% CI: 1.94-5.00, P < 0.01). For patients with severe symptoms needing bougie dilatation, prevalence was still significantly higher after LNF than after LTF (7.91% vs 1.44%, OR 3.67, 95% CI: 1.90-7.09, P < 0.01). We thought it necessary to carry out subgroup analyses because preoperative EM was an important variable in the choice of surgical procedure and may have an effect on the analyses. Defining esophageal dysmotility was not consistent in the surgical literature. Most surgeons would agree that a distal esophageal amplitude > 40 mmHg and peristaltic contraction of the esophageal body of at least 70% indicate normal motility[18]. As described above, subgroup 1 analysis showed that the surgical procedure had no effect on the occurrence of postoperative dysphagia if preoperative EM was normal (P = 0.89). However, in subgroup 2, patients with abnormal EP, the prevalence of dysphagia after LNF was still more common than after LTF (P = 0.04). In subgroup 3, even though the surgical choice was in accordance with the so-called “tailored procedure”, LNF also led to a significantly higher risk of developing postoperative dysphgia than LTF (P = 0.03) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Pooled analysis using the Mantel-Haenszel method and a random-effect model. A: Overall rates of dysphagia after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF) and laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication (LTF); B: Subgroup dysphagia depending on preoperative esophageal motility after LNF and LTF; C: Postoperative gas bloating and inability to belch after LNF and LTF.

Gas-bloat syndrome or gas-related symptoms: Gas-related symptoms (“gas-bloat syndrome”) were described in 12 studies involving > 1200 patients. Gas-bloat syndrome included gas bloating, inability to belch, flatulence, postprandial fullness, and epigastric pain. The main objective evaluation of gas-related symptoms was done using a verbal rating scale using the items mentioned above. Overall, 47.39% (327/690) of patients after LNF and 26.09% (138/529) of patients after LTF suffered from gas bloating, whereas 37.22% (220/591) after LNF and 22.24% (109/490) after LTF were unable to belch. Gas bloating and inability to belch were more common in the LNF group and a significant difference between LNF and LTF was also further confirmed to reach a significant level (Figure 2C).

Recurrence and re-operation

Heartburn and reflux recurrence: Eleven studies investigated the incidence of postoperative heartburn (considered to be the cardinal symptom of GERD recurrence). Heartburn occurred in 6.45%[26]-60.29%[43] of the population after LNF, and in 5.26%[25]-55.10%[43] after LTF. No statistically significant difference was found between LNF and LTF concerning the cumulative prevalence of heartburn (32.97%, 331/1004 vs 31.09%, 157/505, OR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.52-1.33, P = 0.45, respectively).

Nine studies reported the postoperative recurrence of GERD. However, the standard of GERD recurrence was not uniform because some were judged according to symptoms such as reflux, chest pain, and heartburn, whereas others were based on the endoscopic characteristics and 24-h gastric monitoring of pH (e.g. persistent esophagitis, DeMeester score[46]). In our analysis, the cumulative prevalence of reflux recurrence was slightly higher after LTF than after LNF, but this difference was not significant (6.50%, 64/985 vs 9.42%, 84/892, OR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.35-1.53, P = 0.40).

Re-operation: Re-operation prevalence was described in 15 trials involving > 3800 patients. The main causes of re-operation were persistent dysphagia, severe reflux symptoms, hiatus hernia recurrence, and other severe treatment failures. Although the re-operation rate after LNF was slightly higher than after Toupet fundoplication, 4.40% (115/2616) vs 3.68% (47/1276), the difference was not significant (OR 1.29, 95% CI: 0.73-2.29, P = 0.38). The morbidity associated with re-operation after LNF for GERD ranged from 1.56%[21] to 27.27%[41], and in the LTF group the rates varied from 1.00%[28] to 17.5%[22].

DISCUSSION

Lower morbidity and mortality, shorter hospitalization and faster convalescence made LARS so attractive to patients with GERD. Since Nissen procedure was first reported a decade ago, it has been adopted as a tremendously successful procedure for reflux control, and it is therefore more often performed than partial fundoplication. However, numerous recent researches witnessed a strong debate between Nissen and Toupet fundoplications[47], shifting the attention to postoperative failures due to mechanical problems (e.g. dysphagia), rather than worries about the recurrence of disease.

Our analysis is a comprehensive and detailed systematic literature review of 32 articles reporting the surgical outcomes of 6236 patients with GERD after LNF and LTF. It demonstrated that the latter is advantageous over the former, showing similar outcomes of satisfaction rate, endoscopic improvement, perioperative complication occurrence, reflux recurrence and re-operation, but a substantially reduced prevalence of postoperative symptoms (e.g. dysphagia, gas-bloat syndrome).

Patient satisfaction is a reasonable and accurate index for assessing the efficacy of surgical treatment for GERD[11,47]. In our meta-analysis, > 90% of the study populations reported excellent or good results in the LNF and LTF groups. Bearing in mind that the subjective description of patients was not always in accordance with objective findings[48], we further analyzed the alteration of LES pressure and remission of esophagitis after construction of a mechanical anti-reflux barrier. Elevating the resting pressure of the LES played a crucial role in controlling reflux symptoms, blocking the natural history of Barrett’s esophagus and reducing the risk of malignancy. We also found that LNF and LTF could increase the LES pressure and improve preoperative esophagitis. Even though the amplitude of elevation of LES pressure was significantly lower after LTF than after LNF, it seemed that it remained sufficiently powerful to resist the reflux of gastric contents. These subjective assessments and objective evaluations supported the point of view that LTF can control reflux symptoms for GERD.

The prevalence of perioperative complications showed no significant difference between groups, indicating that neither procedure was more technically difficult or more demanding of surgical skills. However, the prevalence of postoperative dysphagia and gas-related symptoms was much higher after LNF than after LTF. Even though the mechanism of gas-related symptoms is unclear[29], these results suggest that wrap type and alteration in LES pressure were the underlying causes.

Dysphagia was still the complication of greatest concern and presented in three scenarios: acute total dysphagia immediately after surgery; mild dysphagia within the first postoperative 6-8 wk; and persistent chronic dysphagia after the postoperative 6-8 wk[18,49-51]. Some authors thought that dysphagia converges and the difference normalizes within 12 mo[52-55]. This study analyzed the prevalence of chronic dysphagia at the end of follow-up, and the mean duration of follow-up of most included studies was > 12 mo. A subgroup analysis was also executed to incorporate the variable of EM. It seemed that in normal motility patients (subgroup 1), extent of anti-reflux barrier did not affect the possibility of dysphagia. But in patients with abnormal motility (subgroup 2), the higher dysphagia rate after LNF supported that the tailored approach should be preserved. Even using the tailored approach (subgroup 3), the prevalence of dysphagia after LTF was still significantly lower than after LNF. These results indicated that, irrespective of EM status, LTF would be a safer choice in reducing this complication.

Concerns regarding GERD recurrence made surgeons select the Nissen technique rather than the Toupet technique for a long time. The similar prevalence of reflux recurrence between LNF and LTF groups in our analyses appeared to confirm the effectiveness of the Toupet procedure from another viewpoint. However, the value of this index may be slightly inferior. A DeMeester score > 14.7 was a generally accepted criterion, but the standards of GERD recurrence of selected researches were not uniform. Some were judged based on symptoms, some on endoscopic manometry. Furthermore, even though specific pH changes in the gastric environment were related to symptoms to some extent, inconsistency of poor correlation between postoperative reflux symptoms and reflux abnormal DeMeester scores were noted in many instances[27,45,48].

For re-operation, we did not divide subgroups according to causes such as recurrence of reflux or complications. The reason was that they were a miserable experience for the patients and also indicated the failure of primary surgery. The re-operation prevalence between the two groups was comparable. A remarkable phenomenon discovered in some studies[16,23,24] was that a large proportion of patients needing re-operation after LNF possessed a intact wrap during surgery with herniation of the wraps into the mediastinum. Nevertheless, it was rarely detected and presented after LTF. The technical issue of a suture between the posterior wall of the wrap and the two crura of the diaphragm, or a suture between the upper portion of the wrap and the anterior edge of the hiatus, has been proposed to maintain the wrap in an adequate abdominal position and to avoid its rotation and migration.

In conclusion, the results of the present meta-analysis suggested that LTF might be the current procedure of choice to treat GERD. It should be advocated as a more physiologic alternative for Nissen repair, allowing a reduced morbidity rate with similar efficacy in reflux control and recurrence. The surgical patterns might be a prior factor to preoperative esophageal motility in affecting the postoperative dysphagia after LARS. More multicenter, randomized controlled trials including objective outcome assessment are required to further confirm the value of LNF and LTF.

COMMENTS

Background

The laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and the laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication are the two major anti-reflux surgical procedures for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). There has been much debate about the superiority of these two techniques.

Research frontiers

A decade ago, Nissen procedure was first reported, then adopted as a tremendous successful procedure for reflux control, and was therefore more often performed than posterior partial fundoplication. However, numerous recent researches witnessed a strong debate about Nissen and Toupet fundoplication, shifting the attention to postoperative failures due to mechanical problems (e.g. dysphagia), rather than worries about the recurrence of disease.

Innovations and breakthroughs

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present study was the most comprehensive and detailed systematic literature review to demonstrate the optimal surgical procedure for GERD.

Applications

The research showed that laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication might be the current procedure of choice to treat GERD. It should be advocated as a more physiologic alternative for Nissen repair, allowing a reduced morbidity rate with similar efficacy in reflux control and recurrence.

Peer review

This article is important and interesting.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Marcelo A Beltran, MD, Chairman of Surgery, Hospital La serena, PO Box 912, La Serena, IV Region, Chile

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Dodds WJ, Dent J, Hogan WJ, Helm JF, Hauser R, Patel GK, Egide MS. Mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1547–1552. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212163072503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Watanabe Y, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, Matsumoto T, Nishikawa H, Arakawa T. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:26–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim N, Lee SW, Cho SI, Park CG, Yang CH, Kim HS, Rew JS, Moon JS, Kim S, Park SH, et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for erosive oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease: a nationwide multicentre prospective study in Korea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:173–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JC. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: an Asian perspective. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1785–1793. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts KE, Duffy AJ, Bell RL. Controversies in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux and achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3155–3161. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i20.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nissen R. [A simple operation for control of reflux esophagitis.] Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1956;86:590–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, Markiewicz S, Lombard R. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zügel N, Jung C, Bruer C, Sommer P, Breitschaft K. A comparison of laparoscopic Toupet versus Nissen fundoplication in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;386:494–498. doi: 10.1007/s00423-001-0259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laws HL, Clements RH, Swillie CM. A randomized, prospective comparison of the Nissen fundoplication versus the Toupet fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg. 1997;225:647–653; discussion 654. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199706000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamolz T, Granderath FA, Bammer T, Wykypiel H Jr, Pointner R. "Floppy" Nissen vs. Toupet laparoscopic fundoplication: quality of life assessment in a 5-year follow-up (part 2) Endoscopy. 2002;34:917–922. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wetscher GJ, Glaser K, Wieschemeyer T, Gadenstaetter M, Prommegger R, Profanter C. Tailored antireflux surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease: effectiveness and risk of postoperative dysphagia. World J Surg. 1997;21:605–610. doi: 10.1007/s002689900280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patti MG, De Pinto M, de Bellis M, Arcerito M, Tong J, Wang A, Mulvihill SJ, Way LW. Comparison of laparoscopic total and partial fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:309–314; discussion 314-315. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(97)80050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horvath KD, Jobe BA, Herron DM, Swanstrom LL. Laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication is an inadequate procedure for patients with severe reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(99)80079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baigrie RJ, Cullis SN, Ndhluni AJ, Cariem A. Randomized double-blind trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus anterior partial fundoplication. Br J Surg. 2005;92:819–823. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strate U, Emmermann A, Fibbe C, Layer P, Zornig C. Laparoscopic fundoplication: Nissen versus Toupet two-year outcome of a prospective randomized study of 200 patients regarding preoperative esophageal motility. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bessell JR, Finch R, Gotley DC, Smithers BM, Nathanson L, Menzies B. Chronic dysphagia following laparoscopic fundoplication. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1341–1345. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novitsky YW, Wong J, Kercher KW, Litwin DE, Swanstrom LL, Heniford BT. Severely disordered esophageal peristalsis is not a contraindication to laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:950–954. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meneghetti AT, Tedesco P, Damani T, Patti MG. Esophageal mucosal damage may promote dysmotility and worsen esophageal acid exposure. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbella FA, Tedesco P, Nipomnick I, Fisichella PM, Patti MG. Effect of partial and total laparoscopic fundoplication on esophageal body motility. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:285–288. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth MI, Stratford J, Jones L, Dehn TC. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic total (Nissen) versus posterior partial (Toupet) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease based on preoperative oesophageal manometry. Br J Surg. 2008;95:57–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mickevicius A, Endzinas Z, Kiudelis M, Jonaitis L, Kupcinskas L, Maleckas A, Pundzius J. Influence of wrap length on the effectiveness of Nissen and Toupet fundoplication: a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2269–2276. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9852-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fibbe C, Layer P, Keller J, Strate U, Emmermann A, Zornig C. Esophageal motility in reflux disease before and after fundoplication: a prospective, randomized, clinical, and manometric study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:5–14. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zornig C, Strate U, Fibbe C, Emmermann A, Layer P. Nissen vs Toupet laparoscopic fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:758–766. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chrysos E, Tsiaoussis J, Zoras OJ, Athanasakis E, Mantides A, Katsamouris A, Xynos E. Laparoscopic surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease patients with impaired esophageal peristalsis: total or partial fundoplication? J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:8–15. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guérin E, Bétroune K, Closset J, Mehdi A, Lefèbvre JC, Houben JJ, Gelin M, Vaneukem P, El Nakadi I. Nissen versus Toupet fundoplication: results of a randomized and multicenter trial. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1985–1990. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw JM, Bornman PC, Callanan MD, Beckingham IJ, Metz DC. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic Nissen and laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:924–932. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0700-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coster DD, Bower WH, Wilson VT, Brebrick RT, Richardson GL. Laparoscopic partial fundoplication vs laparoscopic Nissen-Rosetti fundoplication. Short-term results of 231 cases. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:625–631. doi: 10.1007/s004649900408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granderath FA, Kamolz T, Granderath UM, Pointner R. Gas-related symptoms after laparoscopic 360 degrees Nissen or 270 degrees Toupet fundoplication in gastrooesophageal reflux disease patients with aerophagia as comorbidity. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wykypiel H, Hugl B, Gadenstaetter M, Bonatti H, Bodner J, Wetscher GJ. Laparoscopic partial posterior (Toupet) fundoplication improves esophageal bolus propagation on scintigraphy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1845–1851. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter JG, Swanstrom L, Waring JP. Dysphagia after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. The impact of operative technique. Ann Surg. 1996;224:51–57. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radajewski R, Hazebroek EJ, Berry H, Leibman S, Smith GS. Short-term symptom and quality-of-life comparison between laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplications. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:84–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamolz T, Bammer T, Wykypiel H Jr, Pasiut M, Pointner R. Quality of life and surgical outcome after laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplication: one-year follow-up. Endoscopy. 2000;32:363–368. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sgromo B, Irvine LA, Cuschieri A, Shimi SM. Long-term comparative outcome between laparoscopic total Nissen and Toupet fundoplication: Symptomatic relief, patient satisfaction and quality of life. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1048–1053. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erenoğlu C, Miller A, Schirmer B. Laparoscopic Toupet versus Nissen fundoplication for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Int Surg. 2003;88:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernando HC, Luketich JD, Christie NA, Ikramuddin S, Schauer PR. Outcomes of laparoscopic Toupet compared to laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:905–908. doi: 10.1007/s004640080007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wykypiel H, Gadenstaetter M, Klaus A, Klingler P, Wetscher GJ. Nissen or partial posterior fundoplication: which antireflux procedure has a lower rate of side effects? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:141–147. doi: 10.1007/s00423-004-0537-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKernan JB. Laparoscopic repair of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Toupet partial fundoplication versus Nissen fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:851–856. doi: 10.1007/BF00843453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patti MG, Robinson T, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Fisichella PM, Way LW. Total fundoplication is superior to partial fundoplication even when esophageal peristalsis is weak. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:863–869; discussion 869-870. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pessaux P, Arnaud JP, Ghavami B, Flament JB, Trebuchet G, Meyer C, Huten N, Champault G. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: comparative study of Nissen, Nissen-Rossetti, and Toupet fundoplication. Société Française de Chirurgie Laparoscopique. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1024–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bell RC, Hanna P, Powers B, Sabel J, Hruza D. Clinical and manometric results of laparoscopic partial (Toupet) and complete (Rosetti-Nissen) fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:724–728. doi: 10.1007/BF00193044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lund RJ, Wetcher GJ, Raiser F, Glaser K, Perdikis G, Gadenstätter M, Katada N, Filipi CJ, Hinder RA. Laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease with poor esophageal body motility. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:301–308; discussion 308. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(97)80049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farrell TM, Archer SB, Galloway KD, Branum GD, Smith CD, Hunter JG. Heartburn is more likely to recur after Toupet fundoplication than Nissen fundoplication. Am Surg. 2000;66:229–236; discussion 236-237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heider TR, Behrns KE, Koruda MJ, Shaheen NJ, Lucktong TA, Bradshaw B, Farrell TM. Fundoplication improves disordered esophageal motility. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fein M, Bueter M, Thalheimer A, Pachmayr V, Heimbucher J, Freys SM, Fuchs KH. Ten-year outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1893–1899. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0659-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fuchs KH, DeMeester TR, Hinder RA, Stein HJ, Barlow AP, Gupta NC. Computerized identification of pathologic duodenogastric reflux using 24-hour gastric pH monitoring. Ann Surg. 1991;213:13–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199101000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Catarci M, Gentileschi P, Papi C, Carrara A, Marrese R, Gaspari AL, Grassi GB. Evidence-based appraisal of antireflux fundoplication. Ann Surg. 2004;239:325–337. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000114225.46280.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khajanchee YS, O'Rourke RW, Lockhart B, Patterson EJ, Hansen PD, Swanstrom LL. Postoperative symptoms and failure after antireflux surgery. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1008–1013; discussion 1013-1014. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.9.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wykypiel H, Bonatti H, Hinder RA, Glaser K, Wetscher GJ. The laparoscopic fundoplications: Nissen and partial posterior (Toupet) fundoplication. Eur Surg. 2006;38:244–249. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varin O, Velstra B, De Sutter S, Ceelen W. Total vs partial fundoplication in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2009;144:273–278. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bell RC, Hanna P, Mills MR, Bowrey D. Patterns of success and failure with laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1189–1194. doi: 10.1007/pl00009618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lundell L. Therapy of gastroesophageal reflux: evidence-based approach to antireflux surgery. Dig Dis. 2007;25:188–196. doi: 10.1159/000103883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pizza F, Rossetti G, Del Genio G, Maffettone V, Brusciano L, Del Genio A. Influence of esophageal motility on the outcome of laparoscopic total fundoplication. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elakkary E, Duffy A, Roberts K, Bell R. Recent advances in the surgical treatment of achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:603–609. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181653a3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vakil N. Review article: the role of surgery in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1365–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]