Abstract

Background

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was developed in the USA. The adequacy of its use in Uganda to guarantee its reliability and validity has not been ascertained.

Aim

Thus the aim of the present study was to adapt the MSPSS scale by testing the validity and reliability of the scale in a Ugandan setting.

Methods

A cross-sectional design was employed and 240 respondents were consecutively recruited from postnatal clinics in Mulago hospital. Analysis of reliability and validity of the adapted MSPSS was done. Cronbach alpha and principal component analyses were respectively generated.

Results

Three subscales of the MSPSS that had been identified in other populations were evident in the Ugandan population. Using the Cronbach's alpha, the MSPSS demonstrated good internal consistency at .83. A dendrogram indicated that all sub items of the MSPSS were inter-linked. Exploratory Factor analysis derived three components. Principal Component analysis using rotated varimax generated high loadings on all subscales.

Conclusion

The adapted MSPSS can reliably be used in Uganda.

Key Words: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived social support (MSPSS), adaptation, social support, validity, reliability

Background

Social support has been given various definitions, encompassing all social relationships1. It has been described as the relationship-transaction between a provider and a recipient for a cause, with the recipient being the beneficiary in this relationship2. Social support is characterized as being emotional, instrumental, informational, appraising of assistance and it enhances social integration3,4. The support can be in information terms, in financial assistance or any construct that satisfies the recipient's individual social needs like self- esteem, affiliation, and approval or moral support5. As a psychological concept, social support comprises of material or instrumental help, which is the provision of tangible materials in the form of money, other materials, or intimate interaction. This latter includes behaviors such as listening, caring, understanding and a show of esteem. It also includes guidance, which is the offering of advice, direction and or information. Finally social support is described as including the provision of feedback about one's behavior, thoughts or feelings and the positive social interaction for the purpose of fun and relaxation6.

Social support is known to moderate the effects of crises in life7. This is done through facilitating the way that individuals cope and adapt. Thus social support acts as a buffer during stressful times like in employment termination, and bereavement. Research findings point to the fact that the level of social support available to a patient with clinical depression will determine recovery8.

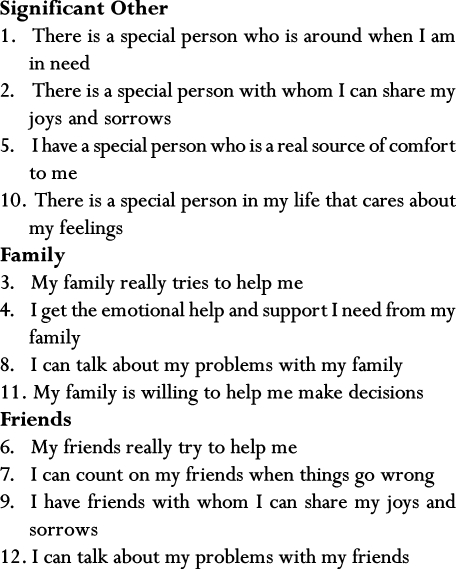

There are currently no instruments that have been adapted in the Ugandan setting to measure social support as most instruments have been developed, and standardized in Western countries. Also there is currently no available local literature that describes the adaptation of these Western-developed instruments in the Ugandan setting. This study, therefore, aimed to adapt the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) to a Ugandan setting. The MSPSS is a brief self report questionnaire with 12 items that subjectively measure perceived social support using three subscales namely: Family subscale, Friends subscale and Significant Others subscale. Each of the three subscales has four items (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Question items of the MSPSS

The MSPSS was developed in the USA by Zimet with a different cultural perspective9. The adequacy of the use of the questionnaire in a culturally appropriate way in Uganda to guarantee the reliability and validity the scale has not yet been established.

Method

Study design

A descriptive cross sectional study design with both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection and analysis was employed for the study. The sampling frame consisted of postpartum mothers with live infants that were attending the two postnatal clinics in Mulago Hospital at six weeks after delivery for purposes of review, immunization of their infants, and family planning counseling. Every second mother waiting in line was recruited into the study. A private room adjacent to the postnatal clinics was used to ensure privacy.

The inclusion criterion was all mothers that turned up for the six weeks postnatal review and mothers that would bring their infants for immunization in the two Mulago postnatal clinics. Mothers that were not able to communicate in Luganda and English the languages that the researchers were fluent in were excluded from the study. In total, two hundred and forty mothers were enrolled for the study. The sample size was determined using Leslie's formula of cross-sectional studies10. A socio demographic questionnaire and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support questionnaire were all interviewer administered to the postpartum mothers. Analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) 11.

Instrument Translation

A Guide to Cultural Adaptation and Translation was used12. A Luganda translator familiar with English and familiar with the terminology used in the MSPSS and who was good in interview skills translated the MSPSS into Luganda. The use of technical terms that might be difficult to understand by Luganda speakers in everyday life was avoided. Two bilingual panels were convened independently to identify and resolve contentious expressions and concepts in the forward translated Luganda versions of the MSPSS. The two panels constituted of the original translators, experts in mental health (Psychiatry, and Behavioral Sciences from the Department of Psychiatry of Makerere University) as well as experts in translation from the Institute of Languages of Makerere University.

The Luganda version of the MSPSS, which was derived from the two expert panels, was then back-translated into English by other independent translators with no knowledge of the MSPSS. Emphasis in translation during the whole exercise was on conceptual equivalence.

Development of a visual illustration of the MSPSS Likert scale

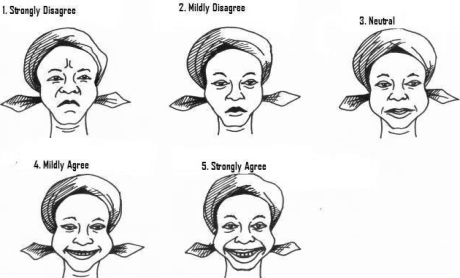

The original English version of the MSPSS9 had a 7 point Likert scale that ranged from 1- of very strongly disagree, 2- strongly disagree, 3- mildly disagree, 4- neutral, 5-mildly agree, 6- strongly agree to 7- very strongly agree. These appeared too many and would be difficult for especially illiterate mothers. During the adaptation of the scale, these were merged to a 5 point Likert scale that ranged from 1- of strongly disagree, 2- mildly disagree, 3- neutral, 4- mildly agree to 5- strongly agree. In order to further help participants understand the responses, the 5 point likert scale was matched with visual picture illustrations of a woman with different facial emotional expressions. Pictures were hand-drawn, scanned, and then altered using computer imaging to obtain the desired emotional expressions that corresponded to the responses as shown in Figure 2. In addition, the Luganda captions were added to the picture illustrations.

Figure 2.

Visual illustration of facial expressions depicting agreeableness to proposed responses on the MSPSS

Scores of the MSPSS were obtained by generating the totals for individual participants and means for the individual subscales were then derived.

Pre testing the MSPSS

The illustrated Luganda version of the MSPSS was pre-tested on 20 Luganda speakers. The participants were involved in a debriefing about the MSPSS. They discussed what they thought the particular items on the MSPSS were asking for. They were also asked to paraphrase the different items in their own words. Participants gave explanations of why they answered the way they did for the different items they had responded to in the MSPSS. For consistency, participants' responses in the debriefing were compared to their actual responses on the MSPSS. Participants were finally asked about any terms that were not clear. If there were alternative terms, which the pre-test participants preferred, they were allowed to decide on these terms for adaptation in the translation.

Ethical clearance to carry out the study was sought from the Faculty of Medicine, Higher Degrees Research and Ethics Committee of Makerere University, Mulago Hospital administration, the two post- natal clinics in Mulago Hospital, the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology and the District Medical Officer of Kampala district. Finally voluntary informed consent was obtained from the mothers both verbally and in writing after the purpose, risks and benefits of the study had been explained to them.

Results

Socio demographic characteristics

Two hundred and forty postpartum mothers were recruited in the study (Table 1). Most of the participants (n = 188, 78.3%) were residents in Kampala district where the study site is located, followed by participants from Wakiso district, the adjacent district to Kampala (n = 40, 16.7%). The mean age of the participants was 26 years (SD 5.7). One hundred and seventy two (71.7%) participants had obtained at least seven years of formal education. Most participants were married (n = 199, 82.9%) and had been in the current relationship for 1–3 years. Relationship was taken to encompass marriage, visiting unions, separated but with infant, and single but in a current relationship. Only 3 participants (1.2%) had been in a current relationship for the past 22 years or more.

Table 1.

Socio demographic characteristics of the participants.

| n | % | |

| Resident district | 188 | 78.3 |

| Kampala | 40 | 16.7 |

| Wakiso | 12 | 5.0 |

| Others | ||

| Age | ||

| 14–19 | 20 | 8.3 |

| 20–25 | 111 | 46.3 |

| 26–31 | 67 | 27.9 |

| 32–37 | 31 | 12.9 |

| 38–43 | 11 | 4.6 |

| Educational level | ||

| No education | 28 | 11.7 |

| Primary (7 years of school) | 88 | 36.7 |

| Ordinary (11 years of school) | 84 | 35.0 |

| Advanced (13 years of school) | 19 | 7.9 |

| Tertiary education | 21 | 8.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 199 | 82.9 |

| Single | 14 | 5.8 |

| Separated | 5 | 2.1 |

| Visiting Union | 22 | 9.2 |

| Occupation of mother | ||

| Salaried | 33 | 13.8 |

| Wage | 7 | 2.9 |

| Housewife | 98 | 40.8 |

| Business | 67 | 27.9 |

| Farmer | 2 | 0.8 |

| Unemployed | 30 | 12.5 |

| Student | 3 | 1.3 |

| Occupation of farther | ||

| Salaried | 64 | 26.7 |

| Wage | 32 | 13.3 |

| Business | 137 | 57.1 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 0.8 |

| Student | 5 | 2.1 |

| Others (Specify) | 0 | 0 |

The majority of the postpartum mothers were housewives and not in paid employment (n = 98, 40.8%). Many of their partners were self employed and doing business, (n = 137, 57.1%) while the smallest number was that of students and the unemployed, (n = 5, 2.1% and n = 2, 0.8%). Most of the postpartum mothers (n = 189, 78.8%) had one to three children and they had been in the current relationship for one to three years (n 83, 34.6%). The majority of mothers (n = 197, 82.1%) resided with the father of the newborn. Twenty-two (9.2%) resided with relatives and 21 (8.8%) by themselves.

Reliability

The means, standard deviations, and the Cronbach's alpha estimates were calculated for the MSPSS subscales and for the entire scale. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means, Standard deviations (SD) and Internal Reliability

| Reliability (Cronbach's alpha) | |||

| MSPSS Subscale |

Mean | SD | Internal Reliability |

| Family | 3.60 | 0.085 | 0.82 |

| Friends | 2.92 | 0.203 | 0.80 |

| Significant other |

4.00 | 0.060 | 0.79 |

| Total Scale | 3.51 | 0.83 | |

The Family, Friends, and Significant other subscales had mean values of 3.6, 2.9, and 4.0 respectively. The total mean score for the complete MSPSS scale was 3.5. The corresponding Cronbach's values for the subscales were 0.82, 0.80, and 0.79 for Family, Friends, and Significant Other respectively. “Significant Other” is understood as any person with great importance to an individual's wellbeing as well as self evaluation. Significant Other in the cultural context in which the study was done could be any person ranging from spouse, partner, parent, uncle grandparent or even sibling [13]. The highest mean value was that of Significant Other. Significant Other however had the lowest Cronbach alpha value. This was because the mean has no direct correlation with the reliability of items. The Cronbach's alpha for the total MSPSS scale was 0.83. These values are indicative of good internal consistence of the subscales and the complete MSPSS scale.

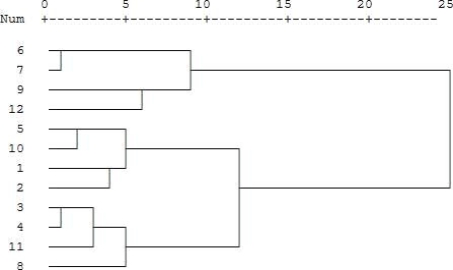

The linkage between MSPSS items

A dendrogram was used to determine the linkage between the different MSPSS items. A dendrogram is a cluster analysis exploratory tool that determines the existing patterns within a given data set. The dendrogram on the MSPSS subscale items showed that all the 12 items were interlinked (Diagram 1). Subscale items 3, 4, 11, and 8 were closely interlinked and measured Family Social Support on the MSPSS. Subscale items 6, 7, 9 and 12 were clustered together and measured the Friends Social Support on the MSPSS. Finally, items 5, 10, 1 and 2 measured the Significant Other subscale.

Diagram 1.

Dendrogram showing Average Linkage (Between Groups) Rescaled Distance Cluster Combine

Results for the Family, Friends, and Significant Other subscales indicated how closely items in each subscale were near each other in terms of what they measure.

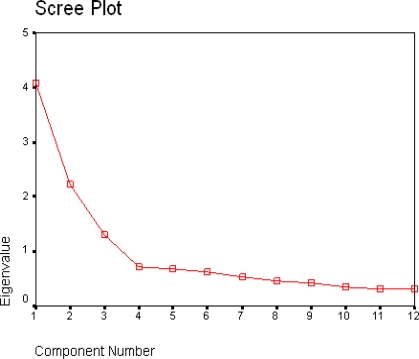

Exploratory Factor analysis to determine the number of factors in the MSPSS was done and a scree plot was generated. The scree plot identified three factors in the MSPSS, i.e. Family, Friends and Significant Other (See Diagram 2).

Diagram 2.

Scree Plot showing the number of factors loading on the MSPSS in the Ugandan setting

A scree plot is a line segment that shows the fraction of total variance in the items. The X axis showed the principal components in the MSPSS of social support and these were sorted by decreasing fraction of the total variance the further away they were on the right. The Y axis showed the total variance of the items. The proportion of variance was considered significant if it was greater than 1 at the point that the curve bent off on the right. This was at an intersection of an eigenvalue of 1.3 on the Y-axis and a component number of 3 on the X axis. Three principal components were identified in the MSPSS.

Factor Analysis using principal component rotated varimax analysis was performed and the three identified factors of Family, Friends, and Significant Other on the complete MSPSS scale were extracted in this population.

All three factors loaded highly on the MSPSS (See Table 3). The results from Principal Component analysis also indicated the three-factor structure of the MSPSS in the Ugandan setting as is evidenced in table 3 of the factor loadings.

Table 3.

Factor loadings using rotated varimax Principal component analysis

| Component | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Family | |||

| I get the emotional help and support I need from my family | .809 | ||

| My family really tries to help me | .777 | ||

| My family is willing to help me make decisions | .755 | ||

| I can talk about my problems with my family | .755 | ||

| Friends | |||

| My friends really try to help me | .816 | ||

| I can count on my friends when things go wrong | .815 | ||

| I can talk about my problems with my friends | .772 | ||

| I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows | .747 | ||

| Significant Other | |||

| There is a special person in my life that cares about my feelings | .839 | ||

| I have a special person who is a real source of comfort to me | .806 | ||

| There is a special person who is around when I am in need | .654 | ||

| There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows | .620 |

NB: Factor loadings below .5 were suppressed during the rotational matrix analysis

Discussion

The study aimed to culturally adapt and test the psychometric properties of the MSPSS in a Ugandan population. The MSPSS was culturally adapted and the three subscales i.e. Family, Friends, and Significant Other that had been identified in a Western population were confirmed in the Ugandan population15. Cronbach alpha was used for assessing the reliability of the MSPSS. Good internal consistence of .82, .80, .79, for the Family, Friends, and Significant Other respectively were obtained in the study.

In a study that investigated the MSPSS's internal consistence in different subject groups of pregnant women, male and female adolescents, and male and female pediatric residents, internal consistence ranged from .81 to .90 for Family, .90 to .94 for Friends, and .83 to .98 for Significant Other16. The internal consistence in this varied group was comparable to the one obtained in this study. The full scale internal consistence was determined at .83. This was comparable to the one in which elderly individuals with and without psychopathology were investigated17. These results show that the MSPSS can reliably be used in a Ugandan setting and they also confirm the cross-cultural stability of the three subscales18.

Exploratory principal component analysis using varimax rotation was performed. Three factors were extracted and they highly loaded on the respective MSPSS subscales and hence they confirmed Zimet's subscale groupings of perceived social support of Family, Friends and Significant Other. These findings were consistent with those obtained in a study on using the MSPSS in youth19. Results of the Factor loadings for the sub scales were similar to previous findings in a developing country15 and in a Western country9. The results indicate that the MSPSS is valid in a Ugandan context.

The Factor analysis results also indicated that postpartum mothers were able to make a distinct difference between alternative sources of social support from Family, Friends and Significant Others. This acted as confirmation of previous work that treated Family, Friends and Significant Others as independent sources of social support9. The definition of significant other has been defined as a set of people in one's social network which include family20 and non-family. Although some mothers could have treated their spouses as Significant Others they were still able to make a distinction between family social support and social support from significant others using the MSPSS. The study findings indicate the need to consider sources of social support for individuals because overall social support may be influenced by the different sources of Family, Friends and Significant Others16.

The MSPSS was translated back and forth into Luganda. The fact that the translated version yielded results comparable to other studies9,16 is indicative that the Luganda version was successfully translated and that the basic concepts and ideas of perceived social support in a Western population did apply to the Ugandan setting.

Limitations

The study was done on a unique population of new mothers and therefore the results may not be generalizable to all mothers due to the changing demands of motherhood that are sometimes dependent on the age of the baby. The results may also not be generalizable to males since it was performed on females exclusively. However, considering that the adaptation of the MSPSS was done as a background study to a larger study that aimed to explore the influence of psychoeducation on postpartum mothers with psychotic illness, postpartum mothers in the two clinics were the closest to the population that was to be studied. Finally the construct validity and the test-retest of the Luganda version of the MSPSS were not carried out but then several other studies on the MSPSS have been conducted on its construct validity and its test-retest reliability.

Conclusion

The study tested the adaptability of the MSPSS in a Ugandan context and the findings indicated that the MSPSS could reliably be used to determine perceived social support among Ugandan postpartum mothers. Using a dendogram, it was evidenced that all items in the MSPSS were inter linked and were able to assess for perceived social support. All subscales were linked and they were measuring perceived social support in Family, Friends and Significant Others. The MSPSS is a valid instrument and it can reliably be used in a Ugandan setting.

Recommendations

The psychometric properties of the MSPSS have been tested out in a Ugandan population and the instrument ought to be used when assessing for perceived social support in a Ugandan setting.

Acknowledgements

The study was made possible by funding from SIDA/SAREC. We are also thankful to the study participants, the Faculty of Medicine, Medical Illustrations Department of Makerere University, and the Research Assistants that were involved in the study.

References

- 1.Hutchison C. Social support: factors to consider when designing studies that measure social support. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(6):1520–1526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownell A, Shumaker SA. Social support: An introduction to complex phenomenon. Journal of Social Issues. 1984;40:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.House JS, Kahn R L. Measures and concepts of social support. In: Cohen S, Syme S, editors. Social support and Health. Orlando: Academic press; 1985. pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutrona CE. Stress and social support: in search of optimal matching. Journal of social and clinical Psychology. 1990;9(1):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heitzmann CA, Kaplan R M. Assessment of methods for measuring social support. Health Psychology. 1988;7(1):75–109. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrera M, Ainlay SL. The structure of social support: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Journal of community Psychology. 1983;11:133–143. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198304)11:2<133::aid-jcop2290110207>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1976;38(5):300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brugha T S, Bebbington PE, MacCarthy, et al. Social support and recovery from depressive disorders: a prospective clinical study. Psychological Medicine. 1990;20:147–156. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700013325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimet GD, Dahlem N W, Zimet S G, et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52(1):30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leslie K. Survey Sampling. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinner P R, Gray C D. SPSS 12 Made simple. Havo and New York: Psychology Press; 2004. pp. 409–421. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ainsworth B E, Committee of I.P.A.P.S.R. Guide to Cultural Adaptation and Translation of the International Physical Activity Prevalence study Instruments. University of South Carolina School of Public Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan H. Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. USA: Norton and Company, Inc; 1959. The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards LM. Measuring perceived social support in Mexican American Youth: Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(2):187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eker D, Arkar H. Percieved social support: psychometric properties of the MSPSS in normal and pathological groups in a developing country. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00802040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimet GD, Powell S S, Farley G K, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;53(3 & 4):610–617. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanely MA, Beck J G, Zebb B J. Psychometric properties of the MSPSS in older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 1998;2(3):186–193. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eker D, Arkar H. Percieved social support: psychometric properties of the MSPSS in normal and pathological groups in a developing country. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00802040. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards LM. Measuring perceived social support in Mexican American Youth: Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(2):187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsh BJ. Natural support systems and coping with major life changes. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1980;8:159–172. [Google Scholar]