Abstract

Alveolar macrophages (AMϕs) secrete regulatory molecules that are believed to be critical in maintaining normal lung homeostasis. However, in response to activating signals, AMϕs have been shown to become to highly phagocytic cells capable of secreting significant levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. There is evidence to suggest that susceptibility of Mϕ subpopulations to viral infection, and their subsequent cytokine/chemokine response, is dependent on age of the host. In the present study, we compared bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) replication and induction of cytokine responses in neonatal ovine AMϕs to those cells from isolated adult animals. While neonatal AMϕs could be infected with BRSV, viral replication was limited as previously shown for AMϕs from mature animals. Interestingly, following BRSV infection, peak mRNA levels of IL-1β and IL-8 in neonatal AMϕ were several fold higher than levels induced in adult AMϕs. In addition, peak mRNA expression for the cytokines examined occurred at earlier time points in neonatal AMϕs compared to adult AMϕs. However, the data indicated that viral replication was not required for the induction of specific cytokines in either neonatal or adult AMϕs. TLR3 and TLR4 agonists induced significantly higher levels of cytokine transcripts than BRSV in both neonatal and adult AMϕs. It was recently proposed that immaturity of the neonatal immune system extends from production of pro-inflammatory cytokines to regulation of such responses. Differential regulation of cytokines in neonatal AMϕs compared to adult AMϕs in response to RSV could be a contributory factor to more severe clinical episodes seen in neonates.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, toll-like receptors, alveolar macrophage, ovine lung, neonates

1. Introduction

Infants and young children are commonly infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which causes severe lower respiratory tract infections manifesting itself as acute bronchiolitis and pneumonia (Durbin and Durbin, 2004; Welliver, 1983). Bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) is a major etiological agent of lower respiratory tract disease in calves (Van der Poel et al., 1994). RSV tropism for the lower respiratory tract is supported by active replication within lung epithelial cells, inducing production of mediators that are chemotactic to cells of the immune system. Infiltration of antigen presenting cells, lymphocytes and mononuclear cells are detected within lung tissue after RSV infection (Kurlandsky et al., 1988; Tripp et al., 1999). Within the alveolar space, alveolar macrophages (AMϕs) play a crucial role in clearance of respiratory pathogens as well as the production of pro-inflammatory and immunomodulatory mediators upon stimulation by microorganisms (Wilmott et al., 2000). The presence of AMϕs in the lower respiratory tract enables them to come in contact with RSV. In vivo data from adult humans confirm the presence of RSV within AMϕs of transplant patients (Panuska et al., 1992). AMϕs infected in vitro with RSV has been documented in humans (Panuska et al., 1990), mice (Stadnyk et al., 1997), guinea pigs (Dakhama et al., 1998), and calves (Liu et al., 1999). Production of pro-inflammatory mediators including IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, and RANTES (Becker et al., 1991; Franke-Ullmann et al., 1995; Kann and Hegele, 2003; Miller et al., 2004), and immunomodulatory IL-10 (Panuska et al., 1995) have been described in RSV-infected AMϕs. Recently, it was discovered that human AMϕs can produce IL-4 after phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate and calcium ionophore stimulation (Pouliot et al., 2005). The immunoregulatory mediators that are produced by AMϕs make them a critical cell type with a key role in host defense and the early innate immune response to RSV.

Neonatal infants have an ineffective immune response to RSV, as evidenced by the prevalence of recurrent infections during childhood (Henderson et al., 1979). Disease manifestations in response to RSV infection vary greatly among individual children. Children with severe RSV infections were shown to have predominant type 2 cytokine response leading to progression of the disease (Bendelja et al., 2000; Roman et al., 1997). Older children and adults generally exhibit mild symptoms. Similar age-dependency in disease severity is seen in RSV infections in cattle and sheep. In a previous study, we utilized an in vivo infection model to show that AMϕs isolated from BRSV-infected neonatal lambs express increased levels of IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12p40 mRNA transcripts compared to control animals (Fach et al., 2007), similar to the aforementioned findings reported in other host species. The susceptibility of Mϕs to viral infection, and their subsequent response to infection, is likely dependent on age of the host and differentiation stage of these myeloid lineage cells. To our knowledge, there have been no direct comparisons of neonatal and adult AMϕ responses to RSV infection. In the present study, we first examined whether neonatal and adult ovine AMϕs differed in permissiveness to viral infection. Next, we analyzed cytokine transcriptional profiles induced in BRSV-infected AMϕ isolated from neonate or adult sheep. Finally, BRSV-induced cytokine responses were compared to those induced by UV-inactivated BRSV or TLR agonists (synthetic dsRNA polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid (poly (I:C); TLR3) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; TLR4)).

2. Material and methods

2.1 Viral inoculum

Bovine RSV strain 375 was propagated on adherent bovine turbinate cells. By seven days of incubation or when over 90% of viral induced cytopathic effect was observed, flasks were frozen at −80 °C. Within two days, the flasks were thawed and all media pooled. After thorough mixing and sterile filtration, viral inoculum was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. Using a standard plaque assay, the tissue culture infectious dosage (TCID50), for the virus was determined to be 104.9 TCID50 per mL (3.97 × 104 plaque forming units (pfu)/mL). The viral inoculum was negative for bovine viral diarrhea virus by PCR (not shown). For in vitro studies, BRSV strain 375 was inactivated by UV irradiation using a Stratagene UV Stratalinker 1800 (3000 μwatts/cm2; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) on the auto-crosslink mode. Twenty-two ml of BRSV 375 in a sterile 150 × 15 mm petri dish was irradiated ten times, and the dish was gently swirled each time in between treatments. Inactivation of UV-BRSV was confirmed by testing inoculum on fetal bovine turbinate cells.

2.2 Isolation of alveolar macrophages (AMϕs)

Healthy two to four day old lambs (n=8) and two to nine year old adult sheep (n=7) of mixed Rambouillet and Polypay breeds were used for the following experiments. At the time of necropsy, the lungs were aseptically removed, lavaged with sterile PBS and the collected cells were pipetted into sterile 50 mL conical tubes. Lavaged cells were centrifuged at 805 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were aspirated off and cells resuspended in 5 ml of supplemented medium (SM; RPMI 1640 with 2% lamb serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (all from Gibco, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were transferred to a large (150 × 15 mm) sterile petri dish containing 30 mL of SM. After 2 h incubation at 5% CO2 and 37 °C, any non-adherent cells and the media were aspirated off and adherent AMϕs washed in warm, sterile PBS. The cells were released from the bottom by the addition of PBS and gentle scraping with a sterile rubber policeman. The AMϕs in PBS were pipetted into 50 ml conical tubes and centrifuged at 453 x g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were aspirated off and AMϕs were resuspended in 1-2 ml of AMϕ medium then enumerated on a hemacytometer.

2.3 In vitro stimulation of AMϕs

Sterile, ninety-six well round bottom plates were used for the in vitro assays. AMϕs were adjusted to 1 × 106 cells in 200 μL of SM. The cells were exposed to Escherichia coli LPS O55:B5 (1μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), poly (I:C) (1μg/mL; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), BRSV 375 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5, 1.0, or 2.0, or UV inactivated BRSV 375 (UV-BRSV) at a MOI of 1.0. After 90 min of incubation, BRSV treated wells were washed by aspiration of the supernatant and cells rinsed with warm RPMI. and 200 μL of fresh SM was replenished. Supernatants were collected and 300 μL of RLT buffer, from the RNeasy Mini RNA Isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), were added to cells and collected at 2, 6, 18 and 24 h.

2.4 Immunohistochemistry

Alveolar macrophages (1 ×106 cells) were incubated in chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) with 2 ml SM and BRSV at a MOI of 1. After 90 min incubation at 5% CO2 and 37°C, any remaining extracellular virus and medium was aspirated off and the cells washed in warm RPMI. Two mL of fresh SM was added to each chamber and slides were incubated at 5% CO2 and 37 °C for a total of 24 h. The medium was aspirated off and the slides were washed with PBS and fixed for 10 min with 100% methanol at room temperature. The slides were dried and rehydrated in 1X Tris buffer and blocked with normal goat serum (Kirkegaard Perry Labs, Gaithersburg, MD) for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were washed in 1X Tris buffer and incubated with polyclonal anti-BRSV antibody conjugated to FITC (50 μL; VMRD Inc., Pullman, WA) at 37 °C for 30 min. To visualize nuclei, slides were washed with 1X Tris buffer and incubated with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dilactate (DAPI, 300 nM; Molecular Probes) for 5 min at room temperature. The slides were washed with 1X Tris buffer and cover slips mounted with a 50-50 glycerin and PBS solution. Alveolar macrophages were examined using a Leica TCS-NT confocal scanning laser microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Exton, PA). Images were prepared using Adobe Photoshop version CS and InDesign version 3.

2.5 RSV Plaque Assay

A previously published plaque assay (McKimm-Breschkin, 2004) was utilized in the present study, with the minor modification that primary ovine fetal turbinate epithelial (OFTu) cells were used as the cell type. This was based on results of preliminary viral plaque experiments comparing OFTu cells, bovine turbinate epithelial cells, and human A549 cells. It was determined, that for BRSV, OFTu cells gave the best plaque visualization. Confluent cells were inoculated with BRSV or supernatants from BRSV-infected AMϕs and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The inoculum was removed and 3 ml of overlay (DMEM/F12 + 0.3% agarose) was added to each Petri dish. Samples were incubated up to 6 days at 37°C, 5% CO2. Subsequently, at selected time points postinoculation, cells were fixed overnight with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Following fixation, agarose overlay was decanted, plates rinsed with dH2O, and air-dried. Cells were stained with 0.5% neutral red for 2 h at RT, washed, and allowed to air dry.

2.6 Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Enriched AMϕs were pelleted in sterile 1.5 mL eppendorf tubes. Cells were resuspended in 350 μl of RLT buffer from the RNeasy Mini RNA Isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini RNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Contaminating genomic DNA was removed during RNA isolation using an on-column RNase-Free DNase I digestion set (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was eluted by the addition of 40 μL of DNase-RNase free water. 500 ng to 1 μg of total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed using oligo(dT)12-18 primers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

2.7 Cytokine and BRSV NS2 mRNA real time PCR assays

Primers were designed specifically for SYBR Green quantification using the Primer Select program (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI) with suggested parameters for SYBR Green chemistry that included product size no larger than 100-150 base pairs and a 50°C annealing temperature. Ovine ribosomal protein S15 was chosen as the endogenous control for the genes of interest, which are listed in Table 1. We have used S15 as our endogenous control in several previous publications (Fach et al., 2007; Kawashima et al., 2006; Meyerholz et al., 2006; Sow et al., 2009) and it was previously selected after comparisons to β-actin and GAPDH. In addition, primers were included for a macrophage cell surface antigen, CD14, and cytokeratin 18. Cytokeratins are a subfamily of intermediate filament proteins expressed in the intracytoplasmic cytoskeleton of epithelia. Cytokeratin 18 was included to control for epithelial cell contamination in the lavage cell preparation. Cytokine mRNA transcripts were quantified as previously described (Fach et al., 2007). Briefly, Oligo(dT) cDNA was diluted 1:10 in DNase-RNase free water and 2 μL used for quantification. SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions. An Applied Biosystems 7300 Real Time PCR Systems machine was used with the same amplification conditions for all genes of interest: 10 min at 95 °C, 15 sec at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 1 min at 50 °C, with a dissociation step of 15 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 50°C, 15 sec at 95 °C. All reactions were performed in duplicate. Final relative quantification was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) where the amount of target gene is normalized to an endogenous control (ovine ribosomal protein S15) and expressed relative to control cells (Fach et al., 2007). Primers were validated on the Applied Biosystems 7300 machine by using serial dilutions of total RNA with ovine ribosomal protein S15 and target gene primers, whose values were plotted as the log input amount versus ΔCT values (target gene CT − endogenous control CT) for relative efficiency. Only primers with a slope of less than 0.1 were used, due to similar amplification efficiencies as the endogenous control. Specificity of PCR products was confirmed by sequencing of amplicons.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for ovine target and endogenous control genes

| Primer | Sequence (5′- 3′) | Length (bp) | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β F | ATGGGTGTTCTGCATGAG | 63 | X54796 |

| IL-1β R | AAGGCCACAGGAATCTTG | ||

| IL-4 F | GGACTTGACAGGAATCTC | 80 | Z11897 |

| IL-4 R | CTCAGCGTACTTGTACTC | ||

| IL-6 F | GAGTTGCAGAGCAGTATC | 75 | X62501 |

| IL-6 R | GGCTGGAGTGGTTATTAG | ||

| IL-8 F | AAGCTGGCTGTTGCTCTC | 94 | X78306 |

| IL-8 R | GGCATCGAAGTTCTGTACTC | ||

| IL-10 F | GATGCCACAGGCTGAGAACC | 53 | U11421 |

| IL-10 R | GCGAGTTCACGTGCTCCTTG | ||

| IL-12p40 F | AAGTCACATGCCACAAGG | 72 | AF004024 |

| IL-12p40 R | CACTCCAGAATGAGCTGTAG | ||

| TNFα F | CTCATCTACTCGCAGGTCCTC | 86 | X56756 |

| TNFα R | ACTGCAATGCGGCTGATGG | ||

| RiboS15 F | TACAACGGCAAGACCTTCAACCAG | 105 | * |

| RiboS15 R | GGGCCGGCCATGCTTTACG | ||

| BRSV NS2 F | ACCACTGCTCAGAGATTG | 155 | NC_001989 |

| NS2 R | AATGTGGCCTGTCGTTCATCG |

Ovine ribosomal protein S15 mRNA sequence provided by Dr. Sean Limesand, Dept. of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Perinatal Research Center, Aurora, CO.

F=forward; R=reverse

In sterile eppendorf tubes, 20 μL of total RNA from bRSV 375 inoculum and bRSV oligo(dT) cDNA were treated with RNase If (1 unit μl−1; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) or untreated and all four samples were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The digestion of single stranded RNA was stopped by heating the tubes at 70 °C for 20 min. Removal of the RNase enzyme was performed by Microcon column exclusion (100 U columns; Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were quantified using bRSV NS2 primers and SYBR Green chemistry as previously described (Fach et al., 2007), with the modification that subsequent time points were expressed relative to the 2 h postinfection time point. No amplification of genomic BRSV NS2 was observed (not shown).

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as a fold change relative to control cells or, in the case of bRSV NS2 gene, relative to the 2 h time point. We analyzed the cytokine data for each treatment and gene with the outcome variable (2−ΔΔCT) log transformed. Samples were compared using a one-way ANOVA (Prism, GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was considered to be P < 0.05.

3. Results

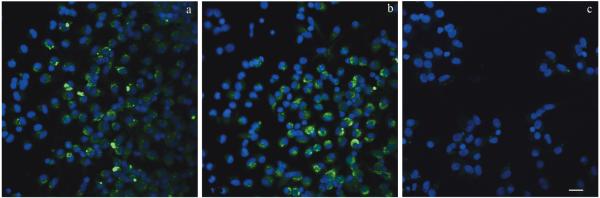

3.1 In vitro immunofluorescence detection of BRSV infected AMϕs

To compare the permissiveness of neonatal and adult AMϕs to bRSV infection, cells were exposed to virus at a MOI of 2 for 90 min. After 24 h of incubation, slides were fixed and subsequently stained using a FITC-conjugated anti-BRSV polyclonal antibody. A subpopulation of neonatal AMϕs expressed BRSV antigen as shown for two individual animals (Fig. 1A and B). BRSV staining was evident in the cytoplasm of infected AMϕs. Alveolar macrophages not exposed to BRSV were included as negative controls as shown for one representative sample (Fig. 1C). Similarly, a subpopulation of BRSV-infected adult AMϕs expressed BRSV antigen as seen in neonatal lamb AMϕs (not shown). Overall, AMϕs from both neonatal lambs and adult sheep are permissive to BRSV infection in vitro. However, additional experiments were utilized to determine whether neonatal AMϕs differed from adult AMϕs in supporting active viral replication after in vitro BRSV infection.

Fig. 1.

Bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) detection in neonatal AMϕs. Neonatal AMϕs were incubated in vitro with BRSV for 90 min. Cells were washed with warm RPMI and replenished with fresh complete medium. After 24 h of incubation, cells were washed and fixed. Cells were stained with FITC-labeled polyclonal anti-BRSV antibody and DAPI for nuclear visualization. Immunofluorescence observed in BRSV-infected AMϕs from two representative individual animals is shown (A, B). A representative micrograph from mock-infected AMϕs is shown in (C). Scale bars: 5 μM.

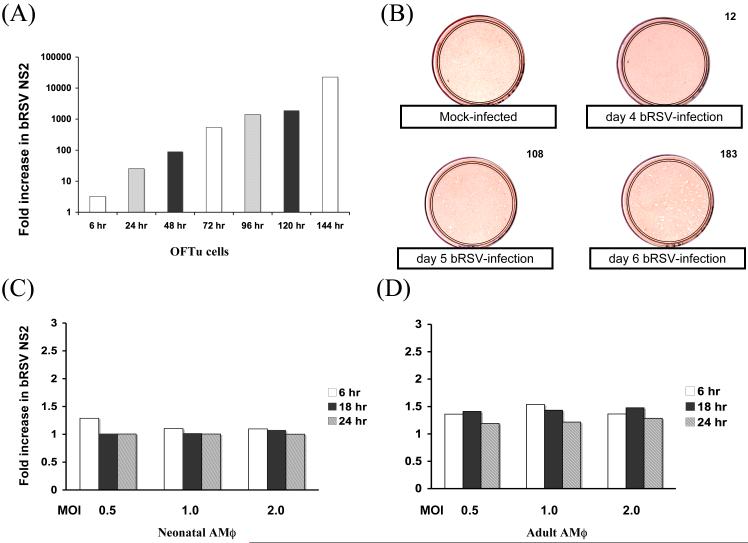

3.2 Validation of BRSV NS2 real-time PCR using primary cells

Upon initiation of replication, the RNA dependent RNA polymerase transcribes the RSV negative sense genome in the 3′ to 5′ direction. Large amounts of the nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2 mRNA are produced during viral replication, as a result of the genome’s transcriptional polarity, where the genes on the 3′ end are transcribed in greater amounts than 5′ genes. Primers were designed to BRSV NS2 mRNA and a real-time PCR assay was used as a measure of BRSV replication in adherent fetal ovine turbinate cells. Data shown for each time point were normalized using an endogenous control and expressed as a fold increase relative to the 2 h time point (Fig. 2A). As can be seen, results of the real-time PCR assay indicated that NS2 mRNA increased in fetal turbinate cells over time. Results of the NS2 real-time PCR assay correlate well with results obtained using a viral plaque assay (Fig. 2B). Earliest viral plaques were visible between day 3 and 4, but were most clearly defined by day 6 of incubation. The data indicate that the NS2 real-time PCR assay can be used as a measure of viral replication.

Fig. 2.

Bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) replication in vitro. A) Fetal ovine turbinate (OFTu) cells were exposed to BRSV and samples harvested at the time points shown. BRSV NS2 mRNA induction was quantified by real-time PCR and data expressed relative to 2 hr timepoint. B) Viral plaque assay using OFTu cells exposed to BRSV. On days 4-6 postinfection, cells were fixed, stained with 0.5% Neutral Red, washed and air-dried. Numbers in the upper right corner are the average number of plaques per plate for duplicate samples. A mock-infected sample is presented for comparison. C) Neonatal (n=8) or D) adult (n=7) AMϕs were exposed to BRSV at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI 0.5, 1.0 or 2.0) for 6, 18, or 24 hr. NS2 mRNA induction was quantified using a real-time PCR assay and data expressed relative to 2 hr timepoint.

3.3 Neonatal AMϕs support limited viral replication in vitro

To detect in vitro viral replication within AMϕs, primers were designed to the NS2 mRNA of BRSV. Adult and neonatal AMϕs were exposed to BRSV in vitro for 90 min and the supernatant was removed. The cells were washed in warm RPMI to remove any remaining extracellular virions and fresh medium was added. The supernatants and cells were harvested after 2, 6, 18 and 24 h of incubation. Data from NS2 real-time PCR assay showed that neonatal AMϕs incubated with BRSV exhibited little viral replication and this did not vary significantly with the different MOI examined in the present study (Fig. 2C). If the NS2 CT values for BRSV were expressed relative to the CT values for UV-inactivated virus there was a significant difference (P < .05), but the fold change did not increase between 2 and 24 h (not shown). Adult AMϕs exposed to BRSV produced similar amounts of NS2 mRNA when compared to the neonatal AMϕs exposed to BRSV (Fig. 2D). In either case, NS2 transcription in BRSV-infected AMϕs was significantly lower at 6 and 24 h than observed for BRSV-infected epithelial cells (Fig. 2A compared to Fig. 2C or Fig.2D). The lack of evidence for substantial viral replication in neonatal or adult AMϕs was confirmed by viral plaque assay using 24 h supernatants from RSV-infected AMϕ cultures added to OFTu cells; there were relatively few plaques observed following the 6 day incubation period (not shown). Taken together, our results indicate that neonatal AMϕ do not support BRSV replication to a greater degree than adult AMϕ as evidenced by data from NS2 real-time PCR and viral plaque assays.

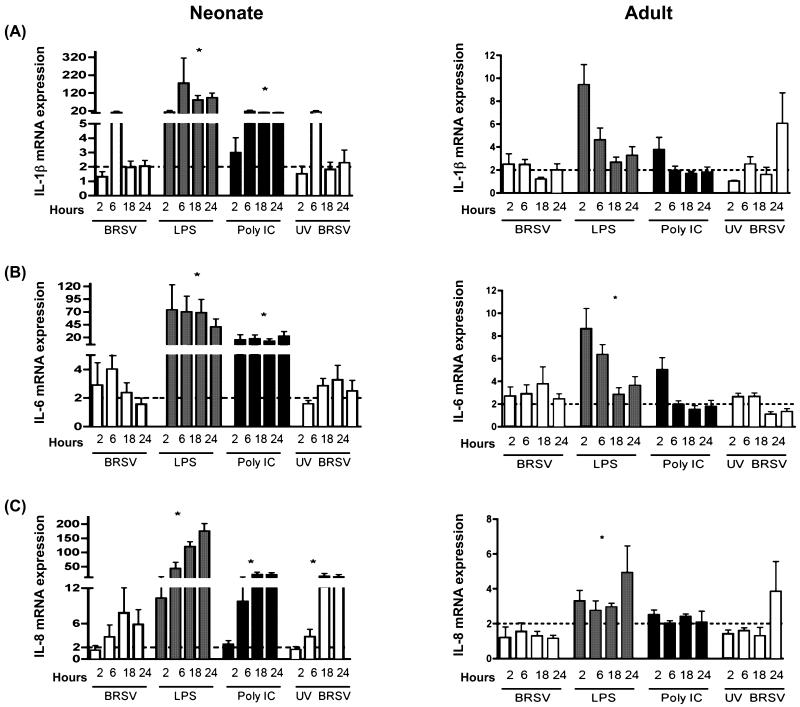

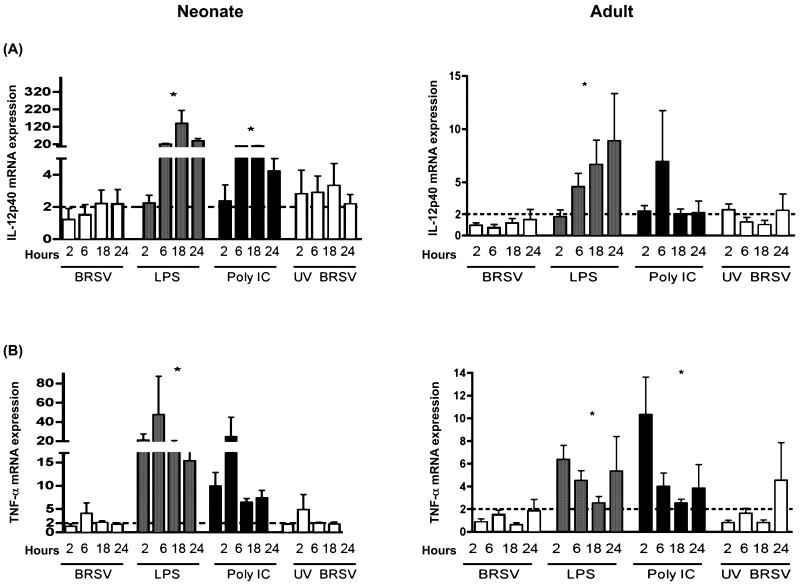

3.4 BRSV induces higher levels of vitro pro-inflammatory cytokine transcripts in neonatal AMϕs compared to mRNA levels induced in adult AMϕs

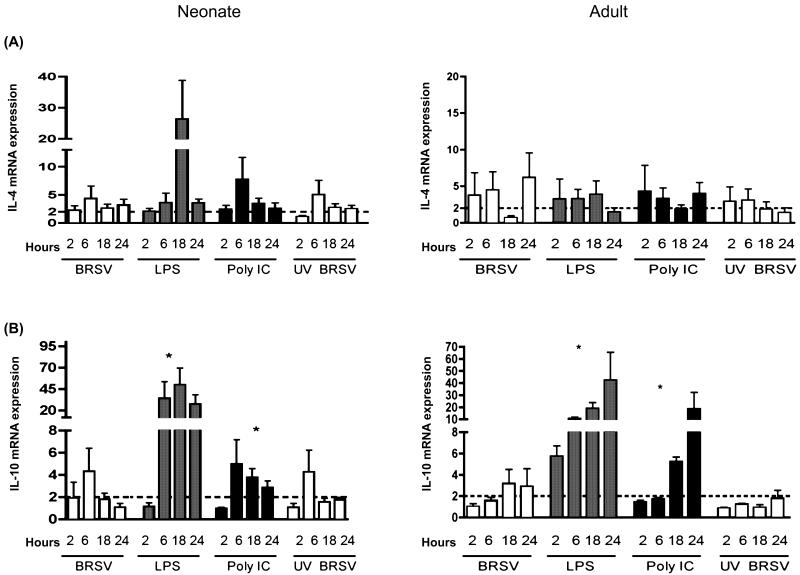

Alveolar Mϕs from neonatal lambs or adult sheep were infected with BRSV and induction of cytokine gene expression at various time points postinfection was determined using real-time PCR assays. To account for the potential for epithelial cell contamination in lavage cell preparations, we included primers for CD14 (macrophage marker) and cytokeratin 18 (epithelial cell marker). AMϕ cell preparations analyzed by RT-PCR did not contain a cytokeratin 18 amplicon, but an epithelial cell control was cytokeratin 18 positive (not shown). Thus, we did find evidence for significant contribution of epithelial cells to adherent BAL cell-derived mRNA. The data shown herein (Fig. 3, 4 and 5) demonstrate that BRSV induced a quantitatively different cytokine mRNA response in neonates than in adults. Of note, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 mRNA transcripts were increased 4-20 fold upon viral infection of neonatal AMϕs (Fig. 3A, B, and C). However, these responses in neonatal AM peaked early and were not sustained, similar to the previous report of Matsuda et al. (1996) showing short-term expression of IL-6 or TNF-α in neonatal cord blood monocyte-derived macrophages. By comparison, a 1-4 fold increase in transcripts for IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 were observed in adult AMϕs. In general, pro-inflammatory IL-12p40 and TNFα gene transcription increased 2-4 fold after BRSV infection of neonatal and adult AMϕs (Fig. 4A and B). For the time points examined, transcription of IL-4 and IL-10 peaked at 6 h postinfection in neonates, but peaked at later timepoints postinfection in adults (Fig. 5A and B). Interestingly, AMϕs exposed to either live BRSV or UV-BRSV expressed similar levels of mRNA transcripts of IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, and TNFα. By comparison, UV-BRSV actually induced significantly more IL-8 gene transcription than live BRSV in neonatal AMϕs. Thus, it is likely that phagocytois of small numbers of RSV virions would be sufficient to trigger an induction of cytokines/chemokines in neonatal AMϕs.

Fig. 3.

IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 mRNA transcript expression in AMϕs in response to bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) or TLR ligation. Shown in each panel are data for cells treated with BRSV (MOI= 2), LPS (1 μg/ml), poly (I:C) (1 μg/ml), or UV inactivated BRSV (MOI=1) for 2, 6, 18, or 24 h. Total RNA was isolated and cytokine induction was quantified by real-time PCR. Data for IL-1β (A), IL-6 (B), or IL-8 (C) are presented as means ± standard errors of the means relative to non-stimulated controls. Results for neonatal AMϕs (n=8) are shown in the left column, whereas results for adult AMϕs (n=7) are shown in the right column. The dotted line in each panel denotes a two-fold induction. ANOVA was used to compare TLR agonists or UV-inactivated BRSV to live BRSV-stimulated cells within each panel for each cytokine (*P<0.05).

Fig. 4.

IL-12p40 and TNF-α mRNA transcripts expression in AMϕs in response to bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) or TLR ligation. Shown in each panel are data for cells treated with BRSV (MOI= 2), LPS (1 μg/ml), poly (I:C) (1 μg/ml), or UV inactivated BRSV (MOI=1) for 2, 6, 18, or 24 h. Total RNA was isolated and cytokine induction was quantified by real-time PCR. Data for IL-12p40 (A) or TNF-α (B) are presented as means ± standard errors of the means relative to non-stimulated controls. Results for neonatal AMϕs (n=8) are shown in the left column, whereas results for adult AMϕs (n=7) are shown in the right column. The dotted line in each panel denotes a two-fold induction. ANOVA was used to compare TLR agonists or UV-inactivated BRSV to live BRSV-stimulated cells within each panel for each cytokine (*P<0.05).

Fig. 5.

IL-4 and IL-10 mRNA transcripts expression in AMϕs in response to bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) or TLR ligation. Shown in each panel are data for cells treated with BRSV (MOI= 2), LPS (1 μg/ml), poly (I:C) (1 μg/ml), or UV inactivated BRSV (MOI=1) for 2, 6, 18, or 24 h. Total RNA was isolated and cytokine induction was quantified by real-time PCR. Data for IL-4 (A) or IL-10 (B) are presented as means ± standard errors of the means relative to non-stimulated controls. Results for neonatal AMϕs (n=8) are shown in the left column, whereas results for adult AMϕs (n=7) are shown in the right column. The dotted line in each panel denotes a two-fold induction. ANOVA was used to compare TLR agonists or UV-inactivated BRSV to live BRSV-stimulated cells within each panel for each cytokine (*P<0.05).

3.5 TLR agonists induced higher levels of cytokine transcripts in neonatal ovine AMϕs compared to mRNA levels induced in AMϕs from adult animals

LPS is a known inducer of TLR4 signaling and poly I:C (synthetic double stranded RNA) has been shown to signal through TLR3. Data from in previous studies have suggested that RSV may induce cytokine production via signaling pathways dependent on TLR3 (Rudd et al., 2005) or TLR4 signaling(Kurt-Jones et al., 2000). Therefore, we were interested to compare responses from AMϕs stimulated with LPS or poly I:C to responses induced by BRSV. Induction of cytokine gene expression at various time points postinfection was determined using real-time PCR assays. In the present experiments, TLR3 or TLR4 agonists induced significantly higher levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and IL-12p40 gene transcription in neonatal and adult AMϕs in comparison to the levels of transcription induced by BRSV infection (Fig. 3, 4, and 5). Moreover, the cytokine induction to TLR agonists was sustained in neonatal AMϕs, whereas the induced cytokine response to BRSV was generally not. In addition, as described for BRSV above, TLR-stimulation of AMϕs isolated from neonates generally exhibited levels of mRNA transcription that exceeded levels seen in adult AMϕs. Of note, levels of peak induction varied based on the specific cytokine examined, the agonist used for stimulation, and age of host from which AMϕs were isolated. Taken together, our results indicate that cytokine/chemokine mRNA expression induced in neonatal AMϕs via TLR3 or TLR4 ligation or BRSV infection was, in general, substantially higher than mRNA transcript levels induced in adult AMϕs.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first to directly compare BRSV infection or TLR ligation and subsequent induction of cytokine responses in neonatal AMϕ to cells isolated from adult animals. Neonatal and adult AMϕs were permissive to BRSV, however, the virus was demonstrated to minimally replicate within these cells. In general, adult AMϕs produced lower levels of cytokine mRNA transcripts after in vitro BRSV infection compared to cytokine transcripts seen in the neonatal AMϕs, especially IL-1β and IL-8 at the peak of their respective responses. Furthermore, peak cytokine mRNA expression occurred at earlier time points in neonatal AMϕs compared to peak cytokine mRNA expression adult AMϕs. Finally, TLR3 and TLR4 agonists induced quantitatively higher levels of pro-inflammatory and immunomodulatory cytokine responses than BRSV in both neonatal and adult AMϕs.

Prior investigators have shown that adult AMϕs can be infected with RSV, but viral replication is generally abortive. Given that neonates exhibit greater susceptibility to RSV infection, a key parameter to evaluate would be permissiveness of neonatal AMϕs to RSV infection compared to cells from adults. To investigate viral infection of AMϕs, in vitro assays utilizing neonatal lamb AMϕs inoculated with BRSV were established for direct comparison to responses induced in adult AMϕs. In vitro studies were necessary since immunocompetent adults are generally not susceptible to RSV. Detection of macrophage infection was determined by immunofluorscence microscopy. The immunofluorescence data shows that different subsets of neonatal AMϕs are permissive to RSV infection. To date, it remains unknown why some AMϕs are not infected with the virus, but one study suggests that the maturation state of AMϕs may influence susceptibility to RSV, with immature AMϕs more permissive to RSV infection (Dakhama et al., 1998). Nonetheless, we observed that minimal replication of BRSV occurred in both neonatal lamb and adult sheep AMϕs infected with the virus in vitro, in agreement with previous studies of adult AMϕs from other species (Franke-Ullmann et al., 1995; Stadnyk et al., 1997). We have demonstrated this by two different approaches; utilizing real-time PCR detection of viral NS2 mRNA or a viral plaque assay using supernatants from AMϕ cultures. Further, we have shown that live virus is generally not required for cytokine mRNA induction. Therefore, differences in cytokine transcriptional profiles induced by RSV in neonatal AMϕs compared to adult AMϕs are not a direct result of differences in viral replication.

Previous studies have reported production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines from AMϕs infected in vitro with RSV. Human, mouse, calf, or guinea pig AMϕs have been utilized for these in vitro assays. Production of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα mRNA and protein is seen in AMϕs after infection with RSV (Becker et al., 1991; Franke-Ullmann et al., 1995; Kaan and Hegele, 2003; Panuska et al., 1995). However, AMϕs utilized in previous studies were isolated from different aged subjects, some using adult human, or adult or juvenile laboratory animals for their studies (Becker et al., 1991; Kaan and Hegele, 2003; Miller et al., 2004; Stadnyk et al., 1997). We are aware of studies in which investigators compared neonatal and adult macrophage responses to RSV. However, in those studies, the authors utilized neonatal cord blood-derived and adult peripheral blood-derived Mϕs (Krishnan et al., 2003; Matsuda et al., 1996; Midulla et al., 1989). Midulla et al. (2003) did examine alveolar macrophages in their study, but only isolated these cells from adult subjects. Our study, for the first time, compares neonate and adult AMϕs in parallel to examine the RSV modulation of cytokine mRNA transcripts. Both neonatal and adult AMϕs produced at least a 2-fold increase in gene expression of IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p40 and TNFα in response to BRSV. However, IL-1β and IL-8 at the peak of their respective responses were found to be several fold higher in neonatal AMϕs than in adult cells. In agreement with our findings, it has been shown that neonatal mice have stronger pro-inflammatory cytokine responses to viral infection than adult mice (Zhao et al., 2008). Moreover, it is interesting to note that IL-1β and IL-8 were found to be the major inflammatory mediators in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of children with chronic respiratory diseases (Babu et al., 2004). IL-1β has numerous pro-inflammatory effects, including induction of chemokines in bronchial epithelial cells and airway smooth muscle (Edwards et al., 2005; Oltmanns et al., 2003; Wuyts et al., 2003). In RSV illnesses in infants, there is a marked increase in neutrophil numbers which is associated with increased levels of IL-8 (Noah et al., 2002).

Discrepancies exist in the literature as to whether live, replicating virus is needed for cytokine induction. In the present study, results indicate that in vitro BRSV replication is not necessary for induction of cytokine gene expression in neonatal or adult AMϕs. Our results are in agreement with previous studies that reported IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα expression is induced by live RSV and UV- or heat-inactivated RSV exposed human or murine primary AMϕs (Becker et al., 1991; Stadnyk et al., 1997). However, these observations are in contrast to one report where investigators using a murine AMϕ cell line showed that live RSV is required for optimal chemokine induction (Miller et al., 2004). This discrepancy between the observations in the study of Miller et al. (2004) and results from other studies, including our own, may plausibly be explained as a difference due to the use of an AMϕ cell line versus the use of primary AMϕs.

In the present study we quantitatively compared BRSV modulated cytokine gene transcription in AMϕs to that induced by TLR3 and TLR4 agonists. Recently, one study has reported RSV induces chemokine production of IL-8 and RANTES via TLR3 signaling in vitro using transfected TLR3 HEK 293 cells (Rudd et al., 2005). RSV was also shown to up regulate expression of TLR3 on epithelial cell lines. TLR3 engagement initiates cytoplasmic recruitment of TRIF, leading to downstream activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB family members and transcription of pro-inflammatory genes (O’Neill, 2006). Other studies have investigated the interaction of RSV and TLR4. Engagement of TLR4 by affinity purified RSV A2 F proteins has been shown in vitro to stimulate production of IL-6 by human monocytes and peritoneal macrophages, though it is unknown whether this occurs specifically on AMϕs since they were not examined in these studies (Kurt-Jones et al., 2000). TLR4 stimulation leads to activation of either MyD88 dependent or independent pathways, subsequent activation of NF-kB family members, and ultimately the transcription of pro-inflammatory mediators (O’Neill, 2006). While studies have demonstrated that RSV activates NF-κB via TLR signaling in epithelial cells, cytokine responses of lung APCs to RSV and TLR agonists have not been compared in parallel. Since RSV may potentially interact with TLR3 and TLR4, it was reasonable to compare the cytokine response elicited by BRSV infection compared to TLR3 or TLR4 stimulation of AMϕs. The data in the present study demonstrate that although BRSV induced an upregulation in the cytokine/chemokine response in AMϕs, modest mRNA transcription was generally observed when compared to that induced via TLR ligation. More importantly, TLR signaling induced higher levels of cytokine transcripts in neonatal AMϕs compared to the induction in adult AMϕs. This data fits well with previous published results showing that neonatal mice have higher inflammatory responses to LPS and poly(I:C) than do adult mice (Zhao et al., 2008). They recently proposed that immaturity of the neonatal immune system extends from production of pro-inflammatory cytokines to regulation of such responses. Based on these observations, it will be of interest to delineate mechanisms involved in cytokine transcriptional regulation in neonatal AMϕs compared to adult AMϕs.

Host cellular recognition of pathogenic microorganisms activates signaling modules that are critically involved in regulating cytokine and chemokine induction within the lung microenvironment. Cytokine and chemokine cross talk in the lung between epithelial cells, professional antigen presenting cells, and other immune cells is important in the outcome and severity of RSV pathogenesis. We have shown a differential induction of the cytokine transcriptional response to RSV infection in neonatal AMϕs compared to AMϕs isolated from adults. Macrophages may be a predominant cell population contributing to severe immunopathology seen in respiratory viral infections. Differential pro-inflammatory cytokine regulation in neonatal myeloid lineage cells compared to analogous cells in adults could contribute to variances in responses to RSV infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH R01 AI062787. Dr. David Meyerholz, LeaAnn Hobbs, Margie Carter, Jim Fosse, and Kim Driftmier are greatly appreciated for their intellectual input and excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Babu PB, Chidekel A, Shaffer TH. Association of interleukin-8 with inflammatory and innate immune components in bronchoalveolar lavage of children with chronic respiratory diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;350:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Quay J, Soukup J. Cytokine (tumor necrosis factor, IL-6, and IL-8) production by respiratory syncytial virus-infected human alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:4307–4312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendelja K, Gagro A, Bace A, Lokar-Kolbas R, Krsulovic-Hresic V, Drazenovic V, Mlinaric-Galinovic G, Rabatic S. Predominant type-2 response in infants with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection demonstrated by cytokine flow cytometry. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:332–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakhama A, Kaan PM, Hegele RG. Permissiveness of guinea pig alveolar macrophage subpopulations to acute respiratory syncytial virus infection in vitro. Chest. 1998;114:1681–1688. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.6.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin JE, Durbin RK. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced immunoprotection and immunopathology. Viral Immunol. 2004;17:370–380. doi: 10.1089/vim.2004.17.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MR, Mukaida N, Johnson M, Johnston SL. IL-1beta induces IL-8 in bronchial cells via NF-kappaB and NF-IL6 transcription factors and can be suppressed by glucocorticoids. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2005;18:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fach SJ, Meyerholz DK, Gallup JM, Ackermann MR, Lehmkuhl HD, Sacco RE. Neonatal ovine pulmonary dendritic cells support bovine respiratory syncytial virus replication with enhanced interleukin (IL)-4 And IL-10 gene transcripts. Viral Immunol. 2007;20:119–130. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke-Ullmann G, Pfortner C, Walter P, Steinmuller C, Lohmann-Matthes ML, Kobzik L, Freihorst J. Alteration of pulmonary macrophage function by respiratory syncytial virus infection in vitro. J Immunol. 1995;154:268–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson FW, Collier AM, Clyde WA, Jr., Denny FW. Respiratory-syncytial-virus infections, reinfections and immunity. A prospective, longitudinal study in young children. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:530–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903083001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaan PM, Hegele RG. Interaction between respiratory syncytial virus and particulate matter in guinea pig alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:697–704. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0115OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima K, Meyerholz DK, Gallup JM, Grubor B, Lazic T, Lehmkuhl HD, Ackermann MR. Differential expression of ovine innate immune genes by preterm and neonatal lung epithelia infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Viral Immunol. 2006;19:316–323. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Craven M, Welliver RC, Ahmad N, Halonen M. Differences in participation of innate and adaptive immunity to respiratory syncytial virus in adults and neonates. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:433–439. doi: 10.1086/376530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurlandsky LE, French G, Webb PM, Porter DD. Fatal respiratory syncytial virus pneumonitis in a previously healthy child. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:468–472. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.2.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt-Jones EA, Popova L, Kwinn L, Haynes LM, Jones LP, Tripp RA, Walsh EE, Freeman MW, Golenbock DT, Anderson LJ, Finberg RW. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:398–401. doi: 10.1038/80833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Lehmkuhl HD, Kaeberle ML. Synergistic effects of bovine respiratory syncytial virus and non-cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus infection on selected bovine alveolar macrophage functions. Can J Vet Res. 1999;63:41–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda K, Tsutsumi H, Sone S, Yoto Y, Oya K, Okamoto Y, Ogra PL, Chiba S. Characteristics of IL-6 and TNF-alpha production by respiratory syncytial virus-infected macrophages in the neonate. J Med Virol. 1996;48:199–203. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199602)48:2<199::AID-JMV13>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKimm-Breschkin JL. A simplified plaque assay for respiratory syncytial virus--direct visualization of plaques without immunostaining. J Virol Methods. 2004;120:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerholz DK, Kawashima K, Gallup JM, Grubor B, Ackermann MR. Expression of select immune genes (surfactant proteins A and D, sheep beta defensin 1, and toll-like receptor 4) by respiratory epithelia is developmentally regulated in the preterm neonatal lamb. Dev Comp Immunol. 2006;30:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midulla F, Huang YT, Gilbert IA, Cirino NM, McFadden ER, Jr., Panuska JR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human cord and adult blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:771–777. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Bowlin TL, Lukacs NW. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine production: linking viral replication to chemokine production in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1419–1430. doi: 10.1086/382958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noah TL, Ivins SS, Murphy P, Kazachkova I, Moats-Staats B, Henderson FW. Chemokines and inflammation in the nasal passages of infants with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Clin Immunol. 2002;104:86–95. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill LA. How Toll-like receptors signal: what we know and what we don’t know. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns U, Issa R, Sukkar MB, John M, Chung KF. Role of c-jun N-terminal kinase in the induced release of GM-CSF, RANTES and IL-8 from human airway smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:1228–1234. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panuska JR, Cirino NM, Midulla F, Despot JE, McFadden ER, Jr., Huang YT. Productive infection of isolated human alveolar macrophages by respiratory syncytial virus. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:113–119. doi: 10.1172/JCI114672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panuska JR, Hertz MI, Taraf H, Villani A, Cirino NM. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of alveolar macrophages in adult transplant patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:934–939. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.4_Pt_1.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panuska JR, Merolla R, Rebert NA, Hoffmann SP, Tsivitse P, Cirino NM, Silverman RH, Rankin JA. Respiratory syncytial virus induces interleukin-10 by human alveolar macrophages. Suppression of early cytokine production and implications for incomplete immunity. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2445–2453. doi: 10.1172/JCI118302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouliot P, Turmel V, Gelinas E, Laviolette M, Bissonnette EY. Interleukin-4 production by human alveolar macrophages. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:804–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman M, Calhoun WJ, Hinton KL, Avendano LF, Simon V, Escobar AM, Gaggero A, Diaz PV. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants is associated with predominant Th-2-like response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:190–195. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9611050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd BD, Burstein E, Duckett CS, Li X, Lukacs NW. Differential role for TLR3 in respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine expression. J Virol. 2005;79:3350–3357. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3350-3357.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sow FB, Gallup JM, Meyerholz DK, Ackermann MR. Gene profiling studies in the neonatal ovine lung show enhancing effects of VEGF on the immune response. Dev Comp Immunol. 2009;33:761–771. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnyk AW, Gillan TL, Anderson R. Respiratory syncytial virus triggers synthesis of IL-6 in BALB/c mouse alveolar macrophages in the absence of virus replication. Cell Immunol. 1997;176:122–126. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp RA, Moore D, Jones L, Sullender W, Winter J, Anderson LJ. Respiratory syncytial virus G and/or SH protein alters Th1 cytokines, natural killer cells, and neutrophils responding to pulmonary infection in BALB/c mice. J Virol. 1999;73:7099–7107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7099-7107.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Poel WH, Brand A, Kramps JA, Van Oirschot JT. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in human beings and in cattle. J Infect. 1994;29:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(94)90866-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welliver RC. Viral infections and obstructive airway disease in early life. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1983;30:819–828. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmott RW, Khurana-Hershey G, Stark JM. Current concepts on pulmonary host defense mechanisms in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000;12:187–193. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200006000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuyts WA, Vanaudenaerde BM, Dupont LJ, Demedts MG, Verleden GM. Modulation by cAMP of IL-1beta-induced eotaxin and MCP-1 expression and release in human airway smooth muscle cells. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:220–226. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00112002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Kim KD, Yang X, Auh S, Fu YX, Tang H. Hyper innate responses in neonates lead to increased morbidity and mortality after infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7528–7533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800152105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]