Abstract

Cocaine addiction and overdose are a well-known public health problem. There is no approved medication available for cocaine abuse treatment. Our recently designed and discovered high-activity mutant (A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G) of human butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) has been recognized to be worth exploring for clinical application in humans as a potential anti-cocaine medication. The catalytic rate constant (kcat) and Michaelis-Menten constant (KM) for (-)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G BChE (without fusion with any other peptide) have been determined to be 3,060 min-1 and 3.1 μM, respectively, in the present study. The determined kinetic parameters reveal that the un-fused A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant has a ∼1,080-fold improved catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) against (-)-cocaine compared to the wild-type BChE. The ∼1,080-fold improvement in the catalytic efficiency of the un-fused A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant is very close to the previously reported the ∼1,000-fold improvement in the catalytic efficiency of the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant fused with human serum albumin. These results suggest that the albumin fusion did not significantly change the catalytic efficiency of the BChE mutant while extending the plasma half-life. In addition, we have also examined the catalytic activities of the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant against two other substrates, acetylthiocholine (ATC) and butyrylthiocholine (BTC). It has been shown that the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutations actually decreased the catalytic efficiencies of BChE against ATC and BTC, while considerably improving the catalytic efficiency of BChE against (-)-cocaine.

Keywords: Enzyme therapy, hydrolase, drug overdose, cocaine addiction

Introduction

Cocaine abuse is a well-known public health problem. This abused drug is recognized as the most reinforcing of all drugs of abuse [1,2,3]. There is no approved medication specific for cocaine abuse treatment. The disastrous medical and social consequences of cocaine addiction have made the development of an anti-cocaine medication a high priority [4,5] It would be an ideal anti-cocaine medication to accelerate cocaine metabolism producing biologically inactive metabolites via a route similar to the primary cocaine-metabolizing pathway, i.e. cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) in plasma [4,6,7,8,9,10]. However, wild-type BChE has a low catalytic efficiency against naturally occurring (-)-cocaine [11,12,13,14,15]. It is interesting to develop a mutant of human BChE, which may be regarded as a cocaine hydrolase (CocH), with a significantly improved catalytic activity against (-)-cocaine.

Generally speaking, design of a high-activity enzyme mutant is extremely challenging, particularly when the chemical reaction process becomes rate determining for the enzymatic reaction [16,17,18]. For rational design of a mutant enzyme with an improved catalytic activity for a given substrate, one needs to design possible amino acid mutations that can accelerate the rate-determining step of the entire catalytic reaction process [12,19,20] while the other steps are not slowed down by the mutations. The detailed catalytic reaction pathway for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (-)-cocaine was uncovered by extensive MD simulations [12,19] and reaction coordinate calculations [19,20] using quantum mechanics (QM) and hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM). It has been shown that the formation of the prereactive BChE-(-)-cocaine complex (ES) is the rate-determining step of (-)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by wild-type BChE [12,19,21]. Based on this mechanistic understanding, previous efforts for rational design of BChE mutants were focused on how to improve the ES formation process and several BChE mutants [11,12,22] were found to have a ∼9 to 34-fold improved catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) against (-)-cocaine. It has also been demonstrated that the formation of the prereactive BChE-(-)-cocaine complex (ES) is hindered mainly by the bulky side chain of Y332 residue in wild-type BChE, but the hindering can be removed by the Y332A mutation and the Y332G mutation can produce a more significant improvement [12]. The combined computational and experimental data [12,16,19,23] have revealed that the rate-determining step of (-)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the A328W/Y332A and A328W/Y332G mutants is the first step of the chemical reaction process. Therefore, starting from the A328W/Y332A or A328W/Y332G mutant, our further efforts in improving the catalytic efficiency of BChE against (-)-cocaine aimed to decrease the energy barrier for the first reaction step without significantly affecting the ES formation and other chemical reaction steps [16,17,18,20]. We have developed unique computational strategies and protocols based on the virtual screening of rate-determining transition states of the enzymatic reaction to design enzyme mutants with improved catalytic activity, leading to discovery of high-activity mutants of human BChE against (-)-cocaine [23,24,25,26,27].

One of our designed and discovered high-activity mutants of human BChE, i.e. the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant [23], has been validated in vitro and in vivo by an independent group of scientists, i.e. Brimijoin et al. [28], who concluded that this mutant is “a true CocH with a catalytic efficiency that is 1,000-fold greater than wild-type BChE” [28]. Brimijoin et al. fused this BChE mutant at its C-terminus with human serum albumin to extend the plasma half-life of the enzyme and found that the BChE mutant (or CocH) fused with human serum albumin can selectively block cocaine toxicity and reinstatement of drug seeking in rats [28]. All of the experimental data reported by Brimijoin et al. [28] strongly supported the potential therapeutic value of our designed and discovered A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant of human BChE, and they concluded that the enzyme treatment with this mutant “was well tolerated and may be worth exploring for clinical application in humans” [28].

Further, some notable differences existed in the in vitro activity assay on the BChE mutant between Brimijoin et al. [28] and our group [23]. In particular, we performed the in vitro activity assay [23] on the mutant without fusion with any other peptide, whereas Brimijoin et al. [28] carried out the in vitro activity assay on the mutant fused with human serum albumin. In addition, in our previous in vitro activity assay [23], we measured the time-dependent radiometric data associated with a low concentration of [3H](-)-cocaine and fitted the data to the kinetic equation. Such a kinetic assay [23] was designed to quickly estimate the relative kcat/KM values of various BChE mutants without determining the individual kcat and KM values. Based on this simple assay, the un-fused A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant was estimated to have a ∼456-fold improved catalytic efficiency compared to wild-type BChE against (-)-cocaine [23]. In contrast, Brimijoin et al. [29] carried out the standard Michaelis-Menten kinetic analysis by measuring the radiometric data associated with varying concentrations of [3H](-)-cocaine. Their assay allowed determination of the individual kcat and KM values, showing that the mutant fused with albumin has a ∼1,000-fold improved catalytic efficiency against (-)-cocaine compared to wild-type BChE. The difference between the two kcat/KM values, i.e. the ∼456-fold vs ∼1,000-fold improvement, is significant. It remains to determine whether “this difference reflects the albumin fusion or, as seems equally likely, variations in assay methodology” [29].

In the present study, we first aimed to determine the individual kcat and KM values of the un-fused A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant by performing the standard Michaelis-Menten kinetic analysis. Comparison of the kcat and KM values determined for the un-fused mutant with those determined for the fused mutant clearly shows whether the albumin fusion significantly changed the catalytic efficiency of the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant against (-)-cocaine. In addition, we wanted to examine whether the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutations also significantly improve the catalytic efficiency of BChE against other substrates or not. As described below, we have performed both molecular modeling and experimental activity assays to address this question and obtained valuable insights.

Materials and Methods

[3H](-)-cocaine (50 Ci/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). Human embryonic kidney 293T/17 cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ). 3, 3′, 5, 5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was obtained from Sigma (Saint Louis, Missouri). Anti-BChE (mouse monoclonal antibody, Product # HAH002-01) was purchased from AntibodyShop (Gentofte, Denmark) and goat anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugate was from Zymed (San Francisco, CA).

We examined both the wild-type and mutant of human BChE at the same time under the same experimental condition. The proteins (wild-type and mutant of BChE) were expressed in human embryonic kidney cell line 293T/17. Cells were grown to 80-90% confluence in 6-well dishes and then transfected by Lipofectamine 2,000 complexes of 4 μg plasmid DNA per each well. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator for 24 hours and cells were moved to 60-mm culture vessel and cultured for four more days. The culture medium [10% fetal bovine serum in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)] was harvested for the BChE activity assays.

To measure (-)-cocaine and benzoic acid, the product of (-)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by BChE, we used sensitive radiometric assays based on toluene extraction of [3H](-)-cocaine labeled on its benzene ring[30]. In brief, to initiate the enzymatic reaction, 100 nCi of [3H](-)-cocaine was mixed with 100 μl of culture medium. The enzymatic reactions proceeded at room temperature (25°C) with varying concentrations of (-)-cocaine. The reactions were stopped by adding 300 μl of 0.02 M HCl, which neutralized the liberated benzoic acid while ensuring a positive charge on the residual (-)-cocaine. [3H]benzoic acid was extracted by 1 ml of toluene and measured by scintillation counting. Finally, the measured (-)-cocaine concentration-dependent radiometric data were analyzed by using the standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics so that the catalytic parameters (kcat and KM) were determined along with the use of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [31] described below.

Our assays on the catalytic activities of BChE against acetylthiocholine (ATC) and butyrylthiocholine (BTC) are the same as those reported in literature [32]. ATC and BTC stock solutions of 0.2 M were prepared in water and frozen at -20°C Enzymatic hydrolysis of ATC and BTC of varying concentration (5 to 400 μM) was monitored at 450 nm in the presence of 1 mM dithiobisnitrobenzoic acid at 25°C, in 0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.5. Each analysis was repeated for three times. Finally, the measured dose-dependent activity data were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation so that the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) was determined along with the use of the relative enzyme concentrations determined by the ELISA assay.

The ELISA assay in the present study was performed to only determine the relative concentrations of the enzymes (wild-type BChE and its mutant). The ELISA buffers used in the present study are the same as those described in literature [31]. The coating buffer was 0.1 M sodium carbonate/bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.5. The diluent buffer (EIA buffer) was potassium phosphate monobasic/potassium phosphate dibasic buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.9% sodium chloride and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. The washing buffer (PBS-T) was 0.01 M potassium phosphate monobasic/potassium phosphate dibasic buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20. All the assays were performed in triplicate. Each well of an ELISA microtiter plate was filled with 100 μl of the mixture buffer consisting of 20 μl culture medium and 80 μl coating buffer. The plate was covered and incubated overnight at 4°C to allow the antigen to bind to the plate. The solutions were then removed and the wells were washed four times with PBS-T. The washed wells were filled with 200 μl diluent buffer and kept shaking for 1.5 h at room temperature (25°C). After washing with PBS-T for four times, the wells were filled with 100 μl antibody (1:8,000) and were incubated for 1.5 h, followed by washing for four times. Then, the wells were filled with 100 μl goat anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugate complex diluted to a final 1:3,000 dilution, and were incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h, followed by washing for four times. The enzyme reactions were started by addition of 100 μl substrate (TMB) solution [31]. The reactions were stopped after 15 min by the addition of 100 μl of 2 M sulfuric acid, and the absorbance was read at 460 nm using a Bio-Rad ELISA plate reader.

Results and Discussion

To minimize the possible systematic experimental errors of the in vitro kinetic data, we expressed the enzymes and performed kinetic studies with wild-type BChE and the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant under the same condition and compared the catalytic efficiency of A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G BChE to that of wild-type BChE for each substrate. For (-)-cocaine, we examined (-)-cocaine hydrolysis at benzoyl ester group. Michaelis-Menten kinetics of the enzymatic (-)-cocaine hydrolysis at benzoyl ester group was determined by performing the sensitive radiometric assays using [3H](-)-cocaine (labeled on its benzene ring) with varying concentrations of the substrate. The kinetic data (see Table 1) revealed that kcat = 3,060 min-1 and KM = 3.1 μM for (-)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G BChE while the known kinetic parameters (kcat = 4.1 min-1 and KM = 4.5 μM) [11] for (-)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by wild-type BChE were reproduced by the same in vitro activity assay. Thus, A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G BChE has a ∼1,080-fold improved catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM = ∼9.9 × 108 M-1 min-1) compared to wild-type BChE (kcat/KM = ∼9.1 × 105 M-1 min-1) against (-)-cocaine. The ∼1,080-fold improvement in the catalytic efficiency of the un-fused mutant enzyme in this study is very close to the ∼1,000-fold improvement in the catalytic efficiency determined for the albumin-fused mutant enzyme by Brimijoin et al. [28,29], suggesting that the albumin fusion did not significantly change the catalytic efficiency of the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant of BChE.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters determined for the hydrolysis of (-)-cocaine, acetylthiocholine (ATC), and butyrylthiocholine (BTC) catalyzed by wild-type BChE and its A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant.

| Substrate | Enzyme |

KM (μM) |

kcat (min-1) |

kcat/KM (M-1 min-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (-)-cocaine | wild-type BChE a | 4.5 | 4.1 | 9.1 × 105 |

| A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G | 3.1 | 3,060 | 9.9 × 108 | |

| ATC | wild-type BChE b | 29 | 20,200 | 6.9 × 108 |

| A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G | 37 | 9,610 | 2.6 × 108 | |

| BTC | wild-type BChE b | 21 | 29,500 | 1.4 × 109 |

| A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G | 8.3 | 2,800 | 3.4 × 108 |

Further, we wanted to know whether the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutations also change the catalytic efficiency of BChE against other substrates. Hence, we examined the catalytic activities against ATC and BTC through both molecular modeling and experimental studies. The same modeling approach [11] which we used previously to study the acetylcholinesterase (AChE)/BChE binding with acetylcholine (ACh)/butyrylcholine (BCh) was used to examine the BChE-ATC and BChE-BTC binding. The initial BChE structures used in the molecular modeling were prepared based on our previous molecular dynamics (MD) simulation [12] on the enzyme-substrate complex for wild-type BChE binding with ACh in water. Our previous MD simulations [12] on the enzyme-substrate complexes started from the X-ray crystal structure [33] deposited in the Protein Data Bank (pdb code: 1POP). The partial atomic charges for ATC and BTC were calculated by using the RESP protocol implemented in the Antechamber module of the Amber9 package following electrostatic potential (ESP) calculations at ab initio HF/6-31G* level using Gaussian03 program [34].

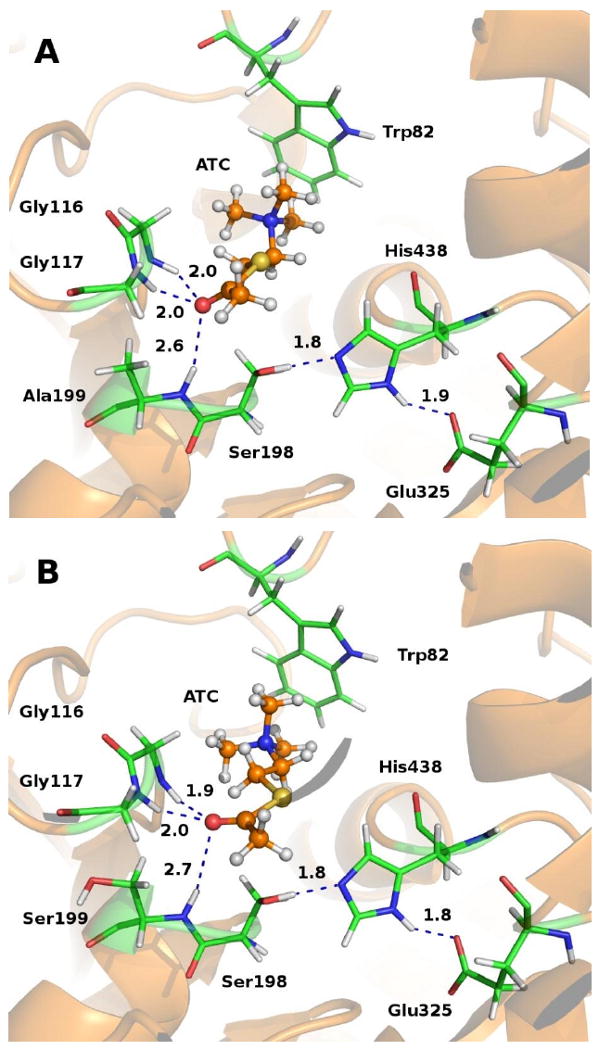

Depicted in Figure 1 are the energy-minimized structures of the BChE-ATC complexes; the corresponding BChE-BTC binding structures (not shown) are similar to these. The structures depicted in Figure 1 suggest that the crucial interactions between the carbonyl oxygen of ATC and the oxyanion hole (residues #116, #117, and #199) in the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant are very similar to the corresponding interactions in the wild-type. The side chain of S199 in the mutant has no favorable interaction with the carbonyl oxygen of ATC or BTC, which is remarkably different from our previously simulated A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G BChE binding with (-)-cocaine [23] where the interaction between the carbonyl oxygen of (-)-cocaine benzoyl ester and the hydroxyl group of S199 is crucial. The molecular modeling results suggest that the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutations are not expected to improve the catalytic efficiency of BChE against ATC or BTC, while considerably improving the catalytic efficiency of BChE against (-)-cocaine. Without a favorable interaction with the substrate, the hydroxyl group of S199, a residue being so close to substrate, could even negatively affect the catalytic activities of the enzyme.

Figure 1.

Modeled structures of the binding of acetylthiocholine (ATC) with wild-type BChE (A) and the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant (B).

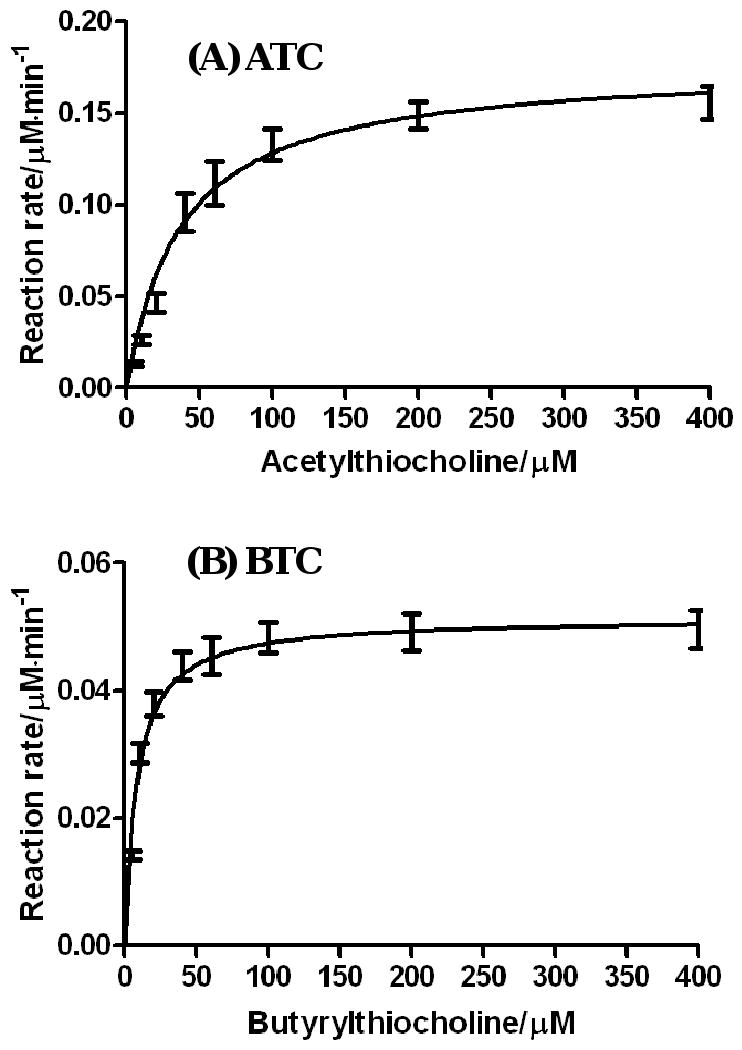

The experimental kinetic data (see Figure 2 and Table 1) obtained for ATC and BTC are qualitatively consistent with the insights obtained from molecular modeling. The kinetic parameters summarized in Table 1 reveal that the determined catalytic activities of the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant against ATC and BTC are all lower than the corresponding catalytic activities of the wild-type BChE. Against ATC, the kcat value (9,610 min-1) of the mutant is less than a half of that (20,200 min-1) of wild-type BChE, while the KM value (37 μM) of the mutant is slightly larger than that (29 μM) of wild-type BChE. Against BTC, the kcat value (2,800 min-1) of the mutant is only ∼9% of the kcat value (29,500 min-1) of the wild-type BChE, although the KM value (8.3 μM) of the mutant is lower than that (21 μM) of wild-type BChE. Overall, the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM = ∼2.6 × 108 M-1 min-1) of the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant against ATC is ∼38% of that (kcat/KM = ∼6.9 × 108 M-1 min-1) of wild-type BChE against ATC, and the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM = ∼3.4 × 108 M-1 min-1) of the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant against BTC is ∼24% of that (kcat/KM = ∼1.4 ×109 M-1 min-1) of wild-type BChE against BTC.

Figure 2.

Kinetic data for the hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine (ATC) and butyrylthiocholine (BTC) catalyzed by the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant of human BChE.

There have been concerns about the therapeutic use of a mutated BChE, fearing that a general enhancement of the BChE function would affect neurotransmission at cholinergic synapses, such as heart, muscle, or even brain. It is interesting to know that the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutation does not affect catalytic function of BChE in general, but selectively enhance the catalytic activity of BChE against (-)-cocaine. The kinetic data obtained in the present study suggest that there should be no real concern about failure of synaptic transmission when this cocaine hydrolase is given for therapeutic treatment of overdose or management of cocaine abuse.

Conclusions

It has been demonstrated that the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutant of human butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) without fusion with any other peptide has a ∼1,080-fold improved catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) against (-)-cocaine compared to the wild-type BChE, and that the albumin fusion did not significantly change the catalytic efficiency of the BChE mutant while extending the plasma half-life. It has also been shown that the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutations selectively and considerably improve the catalytic efficiency of BChE against (-)-cocaine, and that the A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G mutations even decreased the catalytic efficiencies of BChE against other substrates examined in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH (grants R01 DA021416, R01 DA025100, and R01 DA013930). The authors also acknowledge the Center for Computational Sciences (CCS) at University of Kentucky for supercomputing time on an IBM X-series Cluster with 1,360 processors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mendelson JH, Mello NK. Drug Therapy: Management of Cocaine Abuse and Dependence. New Engl J Med. 1996;334:965–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604113341507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh S. Chemistry, design, and structure-activity relationship of cocaine antagonists. Chem Rev. 2000;100:925–1024. doi: 10.1021/cr9700538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paula S, Tabet MR, Farr CD, Norman AB, Ball WJ., Jr Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Modeling of Cocaine Binding by a Novel Human Monoclonal Antibody. J Med Chem. 2004;47:133–142. doi: 10.1021/jm030351z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorelick DA. Enhancing cocaine metabolism with butyrylcholinesterase as a treatment strategy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;48:159–165. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redish AD. Addiction as a Computational Process Gone Awry. Science. 2004;306:1944–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.1102384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijler MM, Kaufmann GF, Qi LW, Mee JM, Coyle AR, Moss JA. Fluorescent Cocaine Probes: A Tool for the Selection and Engineering of Therapeutic Antibodies. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2477–2484. doi: 10.1021/ja043935e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrera MRA, Kaufmann GF, Mee JM, Meijler MM, Koob GF, Janda KD. From the Cover: Treating cocaine addiction with viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10416–10421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403795101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landry DW, Zhao K, Yang GXQ, Glickman M, Georgiadis TM. Antibody-catalyzed degradation of cocaine. Science. 1993;259:1899–1901. doi: 10.1126/science.8456315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhan CG, Deng SX, Skiba JG, Hayes BA, Tschampel SM, Shields GC, Landry DW. First-principle studies of intermolecular and intramolecular catalysis of protonated cocaine. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:980–986. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamendulis LM, Brzezinski MR, Pindel EV, Bosron WF, Dean RA. Metabolism of cocaine and heroin is catalyzed by the same human liver carboxylesterases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:713–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun H, Pang YP, Lockridge O, Brimijoin S. Re-engineering Butyrylcholinesterase as a Cocaine Hydrolase. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:220–224. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamza A, Cho H, Tai HH, Zhan CG. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Cocaine Binding with Human Butyrylcholinesterase and Its Mutants. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:4776–4782. doi: 10.1021/jp0447136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gateley SJ. Activities of the enantiomers of cocaine and some related compounds as substrates and inhibitors of plasma butyrylcholinesterase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;41:1249–1254. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90665-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darvesh S, Hopkins DA, Geula C. Neurobiology of butyrylcholinesterase. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:131–138. doi: 10.1038/nrn1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giacobini E. Butyrylcholinesterase: Its Function and Inhibitors. Dunitz Martin Ltd; Great Britain: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao D, Zhan CG. Modeling evolution of hydrogen bonding and stabilization of transition states in the process of cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by human butyrylcholinesterase. Proteins. 2006;62:99–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.20713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao D, Zhan CG. Modeling effects of oxyanion hole on the ester hydrolyses catalyzed by human cholinesterases. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:23070–23076. doi: 10.1021/jp053736x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao D, Cho H, Yang W. Computational design of a human butyrylcholinesterase mutant for accelerating cocaine hydrolysis based on the transition-state simulation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:653–657. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhan CG, Zheng F, Landry DW. Fundamental reaction mechanism for cocaine hydrolysis in human butyrylcholinesterase. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2462–2474. doi: 10.1021/ja020850+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhan CG, Gao D. Catalytic mechanism and energy barriers for butyrylcholinesterase-catalyzed hydrolysis of cocaine. Biophys J. 2005;89:3863–3872. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.070276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun H, Yazal JE, Lockridge O, Schopfer LM, Brimijoin S, Pang YP. Predicted michaelis-menten complexes of cocaine-butyrylcholinesterase: engineering effective butyrylcholinesterase mutants for cocaine detoxication. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9330–9336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao Y, Atanasova E, Sui N, Pancook JD, Watkins JD, Brimijoin S. Gene transfer of cocaine hydrolase suppresses cardiovascular responses to cocaine in rats. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:204–211. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan Y, Gao D, Yang W. Computational redesign of human butyrylcholinesterase for anti-cocaine medication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16656–16661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507332102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan Y, Gao D, Yang W, Cho H, Zhan CG. Free energy perturbation (FEP) simulation on the transition-states of cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by human butyrylcholinesterase and its mutants. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13537–13543. doi: 10.1021/ja073724k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng F, Yang W, Ko MC. Most efficient cocaine hydrolase designed by virtual screening of transition States. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12148–12155. doi: 10.1021/ja803646t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan Y, Gao D, Zhan CG. Modeling the catalysis of anti-cocaine catalytic antibody: competing reaction pathways and free energy barriers. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5140–5149. doi: 10.1021/ja077972s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang W, Pan Y, Zheng F, Cho H, Tai HH, Zhan CG. Free energy perturbation (FEP) simulation on transition states and design of high-activity mutants of human butyrylcholinesterase for accelerating cocaine metabolism. Biophysical J. 2009;96:1931–1938. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brimijoin S, Gao Y, Anker JJ. A cocaine hydrolase engineered from human butyrylcholinesterase selectively blocks cocaine toxicity and reinstatement of drug seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2715–2725. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao Y, LaFleur D, Shah R, Zhao Q, Singh M, Brimijoin S. An albumin-butyrylcholinesterase for cocaine toxicity and addiction: catalytic and pharmacokinetic properties. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;175:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun H, Shen ML, Pang YP, Lockridge O, Brimijoin S. Cocaine Metabolism Accelerated by a Re-Engineered Human Butyrylcholinesterase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:710–716. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.2.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brock A, Mortensen V, Loft AGR, Nørgaard-Pedersen B. Enzyme immunoassay of human cholinesterase (EC 3.1.1.8). Comparison of immunoreactive substance concentration with catalytic activity concentration in randomly selected serum samples from healthy individuals. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1990;28:221–224. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1990.28.4.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicolet Y, Lockridge O, Masson P, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Nachon FJ. Crystal Structure of Human Butyrylcholinesterase and of Its Complexes with Substrate and Products. Biol Chem. 2003;278:41141–41147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03, Revision C.02. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boeck AT, Schopfer LM, Lockridge O. DNA sequence of butyrylcholinesterase from the rat: expression of the protein and characterization of the properties of rat butyrylcholinesterase. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2002;63:2101–2110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]