Abstract

By phage display, llama-derived heavy chain antibody fragments were selected from non-immune and immune libraries and tested for their affinity and specificity for beta amyloid by phage-ELISA, immunohistochemistry and surface plasmon resonance.

We identified 8 distinct heavy chain antibody fragments specific for beta amyloid. Whilst three of them recognized vascular and parenchymal beta amyloid deposits, the remaining five heavy chain antibody fragments recognized vascular beta amyloid specifically, failing to bind to parenchymal beta amyloid.

These heavy chain antibody fragments, selected from different libraries, demonstrated differential affinity for different epitopes when used for immunohistochemistry. These observations indicate that the llama heavy chain antibody fragments are the first immunologic probes with the ability to differentiate between parenchymal and vascular beta amyloid aggregates. This indicates that vascular and parenchymal beta amyloid deposits are heterogeneous in epitope presence/availability. The properties of these heavy chain antibody fragments make them potential candidates for use in in vivo differential diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Continued use and characterization of these reagents will be necessary to fully understand the performance of these immunoreagents.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid beta, Antibody, Histochemistry, Imaging, Immunoreactivity

1. Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and is characterized by the aggregation of beta amyloid (Aβ) in the form of plaques and neurofibrillary degeneration, including neurofibrillary tangles, dystrophic neurites and neuropil threads. The amyloid cascade theory proposes that Aβ plays a central role in the pathogenesis of AD (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). The deposition of Aβ as primary neuropathologic feature is shared by AD and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), although the location of the deposits differ between the two diseases (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; van Duinen et al., 1987).

CAA describes a group of disorders that is characterized by heterogeneous amyloidogic protein deposition in cerebral vessel walls. CAA is the most common cause of non-hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage in the elderly (Revesz et al., 2002). Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type (HCHWA-D) is a hereditary form of CAA and commonly considered a paradigm for CAA by virtue of being the first familial CAA to be characterized and by far the best described (Bornebroek et al., 1996).

Although AD and CAA frequently coexist in a patient, they generally are distinct clinical and histological entities (Ellis et al., 1996). Growing evidence suggests that patients with severe CAA suffer from cognitive impairment, independent of the presence of AD pathology (Grabowski et al., 2001; Natte et al., 2001).

Currently, neuropathologic examination is required for definitive diagnosis of AD and CAA. Conventional clinical tests are relatively insensitive for the early changes of cerebral amyloidoses, and the changes that are detected are non-specific. With a new generation of neuroprotective agents emerging, there is a need to detect these diseases in early stages.

Molecular imaging techniques specific to amyloid and other structural changes associated with neurodegenerative disease may begin to overcome this predicament, with these techniques relying on agents that are capable of detecting molecular and cellular changes in vivo. It has been demonstrated that agents targeted at Aβ and detectable by PET can detect cerebral Aβ accumulations in patients with AD and CAA (Johnson et al., 2007). However, these agents detect both vascular and parenchymal Aβ, and are thus not well suited to differentiate between AD and CAA.

A relatively new source of immunologic agents has been derived from the Camelid heavy-chain antibody repertoire (HCAb). In addition to conventional immunoglobulins, Camilidae express antibodies which are devoid of light chains. Their single N-terminal domain (VHH) is fully capable of antigen binding with affinities comparable with those reported for conventional antibodies (Hamers-Casterman et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 2004). VHHs have several potential advantages as immunologic tool which might allow them to be used for non-invasive, early and differential in vivo Aβ detection in the brain: because of their small size VHHs rapidly pass the renal filter resulting in a fast blood clearance and rapid tissue penetration; they are reported to be able to cross the blood-brain-barrier (BBB); and they have not shown any immunogenicity in mice (Muruganandam et al., 2002; Stijlemans et al., 2004).

Here we describe the selection of VHHs against Aβ generated from non-immunized animals and from animals immunized with vascular amyloid deposits from a patient with HCHWA-D or grey matter from a patient with Down Syndrome and AD pathologic findings. The intent was to obtain high affinity VHHs specific for distinctive AD or CAA Aβ epitopes. The VHHs selected from the non-immune library solitarily recognize vascular Aβ depositions, similar to VHHs selected from the vascular CAA library. In contrast, the VHHs generated from the grey matter AD library show predominantly high affinity for Aβ epitopes that are specific for, or enriched in parenchymal plaques in addition to vascular deposits.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Selection of antibody fragment by phage display

For the selection of non-immune VHHs an existing llama-derived phagemid library was used, kindly provided by BAC, The Netherlands (Frenken et al., 2000). VHHs were selected in two rounds of micropanning by direct immobilization of Aβ1-42, essentially described before (Verheesen et al., 2006). The selection procedure of the second round of selection was identical to the first round with the exception that 109 input phages and 1ug of antigen was used.

Two Llama-derived immune phagemid libraries were generated. For the vascular CAA library immunization was performed with recombinant beta-amyloid (Aβ1-42, r-peptide, Georgia, USA) and with affected blood vessels of a HCHWA-D patient. For the grey matter AD library, brain parenchyma homogenates of a DS patient with extensive plaque formation was used as the immunogen. Phage display selection from the immune libraries were performed as described for the naive library with the exception that for the vascular CAA library selections 0.2–10ug of different antigens (Aβ1-42, Aβ1-16, Aβ11-22, Aβ25-35 and Aβ17-42, r-peptide, Georgia, USA) and 10ul phages (4.8×108 phages) were used as input. For Aβ1-42 one round of selection was sufficient. One round of selection was performed with the grey matter AD library, with 10 and 50ul input phages and 0.1–10ug antigen (Aβ1-42) coated.

2.2 Phage ELISA and diversity screening of selected VHHs

Phage productions and ELISA were performed as described before (Verheesen et al., 2006). In order to assess the diversity of the selected naive VHHs, DNA fingerprints were obtained as described before (van Koningsbruggen et al., 2003). For the immune VHHs the diversity was screened by means of surface Plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis.

2.3 Epitope mapping of Aβ specific VHHs

Epitope mapping was performed by phage ELISA experiment s as described before (Verheesen et al.,2006). The reactivity of the phage-VHHs is tested on synthetic Aβ fragments 1–40, 1–42, 1–16, 11–22, 22–35, 25–35, 17–42 (rPeptide, Georgia, USA) and control protein. The phage-ELISA data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by a LSD posthoc test. Threshold value for statistical significance was set at p = 0.05. SPSS 15.0.1 was used for all analysis (SPSS for Windows, Rel. 15.0.1. 2006, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

2.4 Subcloning, Production and purification of VHHs

The VHH genes specific for Aβ were subcloned into the pUR 5850VSV production vector (van Koningsbruggen et al., 2003), produced in E. coli and purified from the periplasmic supernatants as described (Kazemier et al., 1996). This vector contains a C-terminal His6 tag for purification and myc tag for detection. Talon metal affinity resin columns (Clontech, CA, USA) were used for purification according to the supplier’s instructions.

2.5 Patient material

Autopsy brain tissue of patients with a genetically confirmed diagnosis of HCHWA-D and patients with AD, CAA, DS or HCHWA-I, and controls were used. The neuropathological evaluation was confirmed by S.G.v.D. and M.L.C.M-S. All HCHWA-D patients gave informed consent to use their tissues for research purposes. Tissue from all other patients and the controls was encoded and used in agreement with the code as defined in the Netherlands (Code Goed Gebruik). For the study of cases from Massachusetts General Hospital, all neuropathologic evaluation was confirmed by M.P.F; tissue was collected and used in the study in accordance with institutional approval for de-identified autopsy tissue.

2.6 Immunohistochemistry

Frozen brain tissue sections (5μm) of DS, HCHWA-D, HCHWA-I, AD, CAA patients and normal control tissue were rinsed in PBS, fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min, incubated with peroxidase blocking reagent (Dako Cytomation) for 20 min, washed in PBS and incubated with the anti-Aβ VHHs (0.625–20ng/ul) in 1% BSA/PBS overnight in a wet chamber. Thereafter, sections were rinsed with PBS and incubated with mouse-anti-VSV (1:1000) or mouse-anti-c-myc (1:6000) for 1 hour and subsequently with EnVision+ ® system labelled Polymer-Hrp anti-Mouse (Dako Cytomation) for 30 min. Detection was performed with Liquid DAB+ Substrate Chromogen System (Dako Cytomation). Hemotoxylin counterstaining was performed and the sections were dehydrated and mounted in micromount mounting medium (Surgipath, Richmond, IL, USA). 4G8 (1:200) and R1282 (1:1500) were used as a positive control for Aβ staining (Haass et al., 1992). Final preparations were analyzed with an Olympus Provis AX70TF light microscope and images were obtained using the Olympus digital DP12 camera.

2.7 Surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy (SPR)

All SPR binding studies were conducted at 25°C in HBS-EP running buffer using a Biacore 3000 biosensor system (GE Healthcare). Aβ1-42 was amine coupled (EDC/NHS) to a CM-5 sensor chip (research grade, GE) using 10 mM NaAc (pH 4.0) as coupling buffer, and HBS-EP as running buffer. Immobilization levels between 150 and 1000 RU could be obtained, however only surfaces of at least 350 RU gave reproducible results. Therefore, we analyzed VHH binding on surfaces at 350, 450 and 1000RU. As a reference channel an unrelated peptide, of the same size as Aβ1-42, derived from the poly A-binding protein nuclear 1 (containing an alpha-helical domain) was immobilized (Kerwitz et al., 2003). Binding experiments of VHHs were performed, using increasing concentration series from 5 nM to 4 μM at a flow rate of 30 μl/min and injection time of 8,3 min to reach equilibrium binding. The surfaces were regenerated after each cycle with two 60-s pulses of 1 M GnHCl and 10 mM NaOH, followed by a stabilization time of 5 min. Biacore data were analyzed with BiaEvaluation v. 4.1 (GE). Reference surface and blanks were subtracted from all binding curves. The dissociation constant (KD) for the interaction between VHHs and Aβ1-42 was measured from saturation binding experiments. The value for KD was obtained using a non-linear least squares analysis (steady state analysis) with ABeq=ABmax (1/(1+KD/[A]) where ABeq is the average of the response signal at equilibrium in defined intervals for each concentration of VHHs [A] and ABmax is the maximum response that can be obtained for VHHs binding depending on the number of binding sites available on the Aβ1-42.

3. Results

3.1 Selection and screening of VHHs

To obtain VHHs from the non-immune library against beta amyloid, two successive rounds of selection were performed by phage display. Synthetic Aβ 1-42 was directly coated onto Nunc maxisorp plates in both rounds. The progress of selection was monitored by colony count of the enriched polyclonal outputs. In each round an increase in output/input ratio was observed, indicative for enrichment of VHHs directed against Aβ 1-42 in the polyclonal phage-pool. After the second round of selection 96 monoclonal phage-clones were randomly chosen. Clones were arrayed and tested for Aβ 1-42 affinity by dot blot analysis (data not shown). Several clones showed specific binding to the antigen. Their diversity was screened by DNA fingerprint analysis showing a large diversity in fingerprint patterns. Subsequently, a subset of clones with different fingerprints was sequenced, resulting in a subset of different VHHs specific for Aβ 1-42. Two of the VHHs, ni3A and ni8B, were chosen for further characterization.

In order to select high affinity VHHs potentially specific for epitopes unique to CAA Aβ, phage selection was also performed utilizing the vascular CAA immune library. For Aβ 1-42 specific VHH, one round of selection was sufficient to obtain high affinity VHHs directed against CAA Aβ epitopes: the output of the selection plate was significantly higher compared with the background plate after one round of selection. In order to aim at a panel of VHHs directed against diverse Aβ epitopes, phage selection was performed with different Aβ fragments. Two successive rounds of selection were necessary judged by the colony count.

Because of the heterogeneous character of Aβ presentation in CAA and AD we also aimed to select VHHs from a library that was generated by immunizing a llama with a protein homogenate of brain parenchyma with extensive AD pathology. We anticipated that, if there are conformational differences between vascular and parenchymal amyloid deposition, this library would yield VHHs with high affinity for AD Aβ epitopes that are specific for parenchymal plaques. Judged by colony count, one round of selection was sufficient for the selection of specific VHHs from this library.

After the selection procedure from the vascular and brain parenchyma libraries, >300 monoclonal phage-clones were randomly chosen from each selection and screened by phage ELISA. Many clones showed specific binding to the antigen. Their diversity was screened by means of off rate differences in SPR analysis. As a consequence of the concentration independence of this parameter, production differences between VHH clones are not of influence. A large diversity in SPR curves was detected. Subsequently, a subset of clones with different off rates was sequenced. This yielded several unique high affinity VHHs specific for their respective antigens (va2E, vaE2 and va1G for the vascular library and pa4D, pa11E and pa2H for the parenchymal library). All selected VHHs were subcloned into the pUR5850-VSV production vector to increase the production yield. The characteristics of all VHHs selected for further analysis are summarized in (table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of VHHs selected from the non-immune, vascular CAA and parenchymal libraries, with their characteristics.

| VHH | Library | Antigen used for selection | Immunohistochemistry | KD Average (nM) | STDV (nM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Aβ reactivity | Parenchymal Aβ reactivity | |||||||

| HCHWA-D | AD | HCHWA-D | AD | |||||

| ni3A | Non-immune | Aβ 1-42 | ++ | ++ | − | − | 39 | 12 |

| ni8B | Non-immune | Aβ 1-42 | ++ | ++ | − | − | 109 | 36 |

| va2E | Vascular | Aβ 17-42 | ++ | + | − | − | 650 | 157 |

| vaE2 | vascular | Aβ 1-42 | ++ | + | − | − | 1180 | 443 |

| va1G | vascular | Aβ 11-22 | ++ | + | − | − | 179 | 73 |

| pa4D | grey matter | Aβ 1-42 | ++ | +++ | − | +++ | 100 | 9 |

| pa11E | grey matter | Aβ 1-42 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | 129 | 45 |

| pa2H | grey matter | Aβ 1-42 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | 160 | 21 |

+ weak intensity, ++ strong intensity, +++ very strong intensity.

3.2 Epitope mapping of Aβ specific VHHs

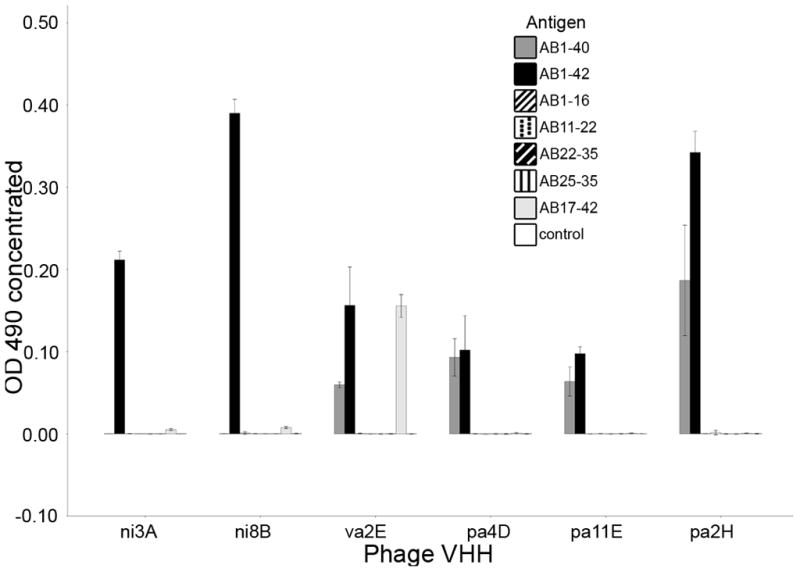

Epitope mapping of the VHHs was performed by phage ELISA experiments. Ni3A and ni8B have a significantly higher affinity preference for Aβ 1-42 compared to all other antigens. Va2E recognizes 1-42 and 17-42 significantly better than other fragments, although Aβ 1-40 recognition is clearly detected. VaE2 and va1G are not phage-VHH ELISA reactive. Pa4D, pa11E, pa2H have affinity preference for Aβ 1-42 and Aβ 1-40 (figure 1). Thus, VHHs selected from the different libraries show distinct epitope specificity, consistent with the distinct immunogens used prior to the phage-ELISA experiment.

Figure 1.

Epitope mapping of Aβ specific VHHs. Depicted are Phage-VHH Elisa results. Data is represented as the corrected OD (minus negative control) measured at 490nm.

3.3 Determination of affinity constants using SPR biosensor analysis

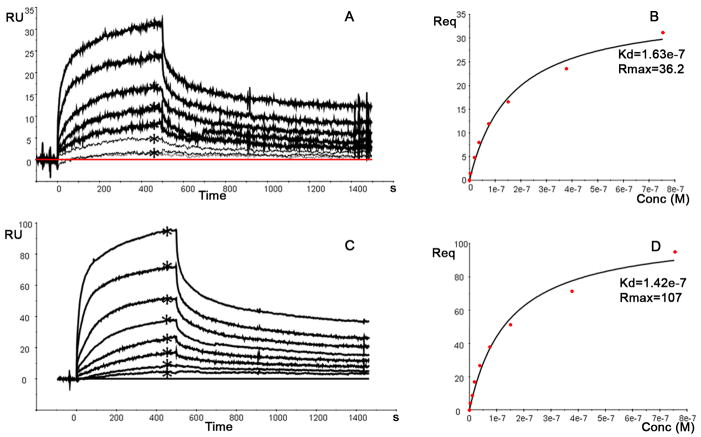

The binding of the various VHHs over a dynamic range of concentrations from 5 nM to 4 μM were determined on three different densities of immobilized Aβ1-42 (350, 450 and 1000 RUs) to evaluate the affinity constant (KD). Sensorgrams with double referenced binding curves of VHH pa11E are shown for the 450 and 1000 RU surface density (Figure 2A and 2C, respectively) and steady state binding (Req) levels were determined (indicated by an asterisks in figure 2A and 2C). The Req levels were plotted versus concentration (Fig 2B and 2D) and subsequently the KD values were determined using steady state analysis. The average of the KDs for all VHHs is summarized in Table 1 and range between 39 and 1200nM. The KD value of each VHH was found to be consistent and independent of the immobilization level of Aβ1-42.

Figure 2.

Example of the binding measurements performed with VHH 11E 0nM to 750nM) to 450 RUs(A) and 100RUs (C) immobilized Aβ 1-42. The sensorgrams were double referenced and Req values were determined (indicated by an asterisk) and plotted versus the concentration (B,D) to evaluate the KD using the steady state analysis provided by BiaEval 4.1.

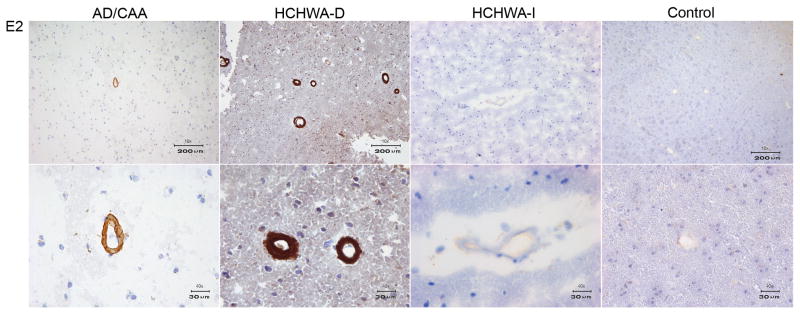

3.4 Immunohistochemistry

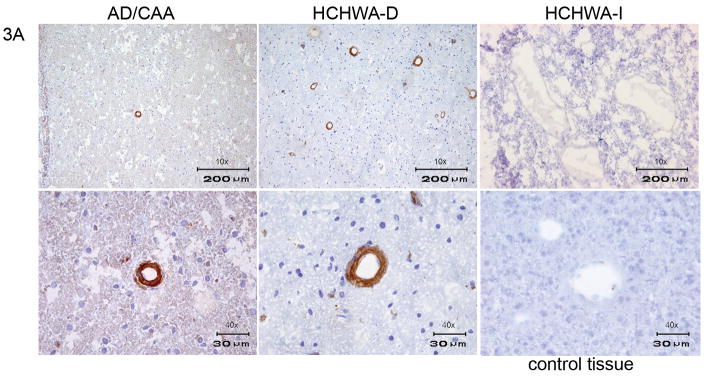

The VHHs directed against Aβ which were derived from the non-immune library (ni3A, ni8B) showed specific staining of vascular Aβ, with equal affinity for these deposits in cases of AD, HCHWA-D and CAA (figure 3), (table 1).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry of VHH ni3A derived from non-immune library. In the upper panel a 10x magnification of AD, HCHWA-D, HCHWA-I cryosections is shown. The lower panel is showing a 40x magnification of AD, HCHWA-D and control tissue cryosections. Ni3A shows immunoreactivity with vascular Aβ in AD and HCHWA-D patient sections. No immunoreactivity was present in HCHWA-I patient sections and control tissue sections.

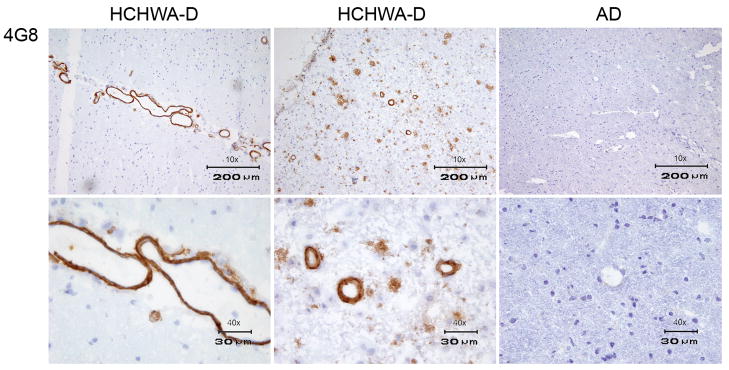

In order to confirm specificity for Aβ and to rule out a contribution from the well-established non-specific endothelial cross-reactivity of the VHHs, immunohistochemistry was performed on control tissue lacking evidence of Aβ deposits. Additionally, staining with a traditional anti-Aβ antibody (4G8/R1282) was performed on adjacent tissue sections. The absence of staining in control tissue and an identical vascular and/or parenchymal staining pattern obtained with 4G8/R1282 in all patients (figure 4) confirmed Aβ specificity. Because conformational specificity has been reported for VHHs selected against Aβ, selected VHHs were also tested on tissue sections of HCHWA-I patients in which the amyloid consists of mutant cystatin (Habicht et al., 2007; Ghiso et al., 1986). Selected VHHs showed absence of staining on HCHWA-I sections and consequently do not detect amyloid epitopes shared by all species of amyloid. Therefore, the selected VHHs are considered to be β-amyloid sequence specific (figures 3,5,6), (table 1).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry with the conventional monoclonal antibody 4G8. The upper panel is showing a 10x magnification and the lower panel a 40x magnification of, from left to right, HCHWA-D with vascular Aβ immunoreactivity, AD with vascular and parenchymal immunoreactivity and control tissue. Identical vascular Aβ staining was observed with VHHs ni3A, ni8B, va2E, vaE2 and va1G. Identical parenchymal staining patterns, in addition to vascular Aβ immune reactivity was observed with VHHs pa2H, pa11E, pa4D.

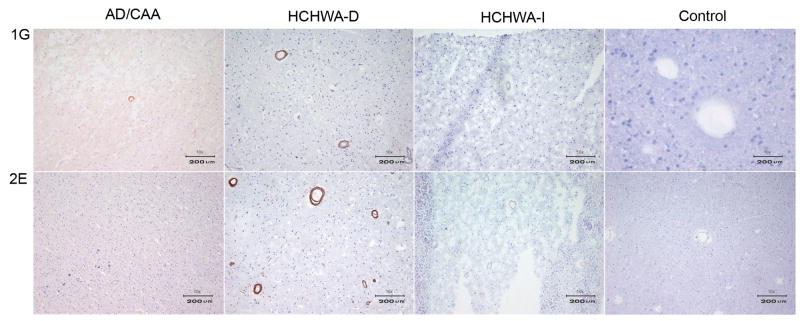

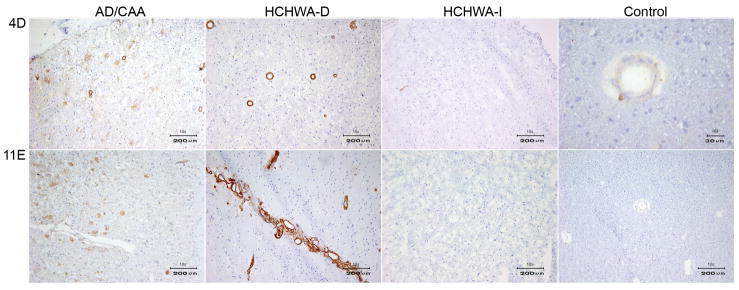

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry of VHH va1G, va2E and vaE2 derived from the vascular amyloid library. A) The upper panel shows a 10x magnification of the immunohistochemical staining with va1G on AD, HCHWA-D, HCHWA-I and control tissue cryosections. In the lower panel a 10x magnification of the immunoreacitivity with va2E on, from left to right, AD, HCHWA-D, HCHWA-I tissue sections and a 40x magnification of the control tissue is shown. B) The upper panel shows a 10x magnification of the immunoreactivity with vaE2 on AD, HCHWA-D, HCHWA-I and control tissue cryosections. In the lower panel a 40x magnification of the immunoreactivity with vaE2 is shown for the same tissue sections. The VHHs in panel A and B show vascular beta amyloid reactivity, with an overall Aβ affinity preference for HCHWA-D patients, especially va2E, which has no immune reactivity for Aβ in AD.

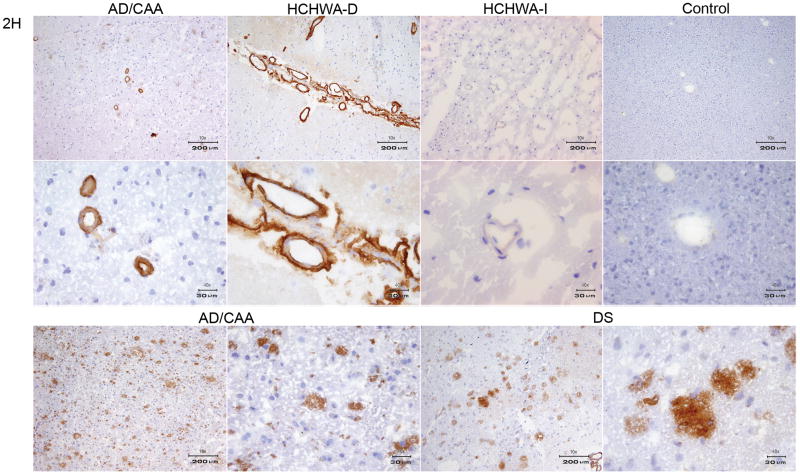

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry of VHH pa4D, pa11E and pa2H, derived from the grey matter library. A) The upper panel shows a 10x magnification of the immunoreactivity with pa4D on AD, HCHWA-D, HCHWA-I and a 10x magnification of control tissue cryosections. In the lower panel a 10x magnification of the staining with pa11E on the same tissue sections from left to right, AD, HCHWA-D, HCHWA-I tissue sections and a 40x magnification of the control tissue is shown. B) All the panels show immunoreactivity VHH pa2H, from on AD, HCHWA-D, HCHWA-I and control tissue cryosections. The upper panel is showing a 10x magnification. In the middle panel the 40x magnification is shown. The lower panel shows 10 and 40x magnifications AD and DS cryosections. The VHHs displayed in panel A and B show high affinity for parenchymal Aβ epitopes, in addition to vascular affinity.

VHHs selected from the vascular CAA library (vaE2, va1G and va2E) showed vascular Aβ immuno-reactivity. In contrast with the non-immune VHHs they displayed a higher affinity for vascular Aβ in HCHWA-D patients when compared with AD (figure 5, table 1).

The VHHs selected from the grey matter AD library (pa2H, pa11E, and pa4D), recognized Aβ epitopes that are specific for, or enriched in parenchymal plaques. In contrast with the VHHs selected from the vascular CAA library, they showed specificity for parenchymal Aβ depositions of AD patients. (figure 6, table 1).

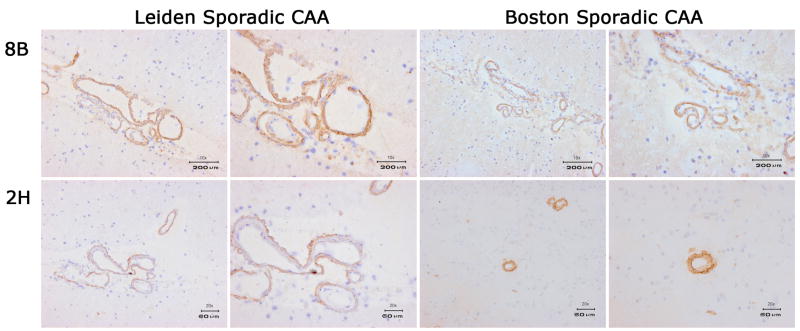

As VHHs derived from post-immunization libraries seemed to show a preference for Aβ deposits which corresponded to the disease state used for immunization, while those from the non-immune library did not show a preference for AD or HCHWA-D Aβ deposits, all VHHs were tested in a larger panel of sporadic CAA patients. An example of immune reactivity of pa2H and ni8B in a series of 4 sporadic CAA patients is shown in figure 7. Pa2H and ni8B also in these patients recognized CAA, like all other VHH derived from the non-immune and parenchymal libraries. We therefore consider the affinity preference for these VHHs to be disease- and not patient-specific. Furthermore, the overall preference for HCHWA-D of the vascular CAA library derived VHH was further corroborated with the observation that only one sporadic CAA patient showed vascular reactivity for these VHHs (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemistry of VHH pa2H and ni8B. VHHs are tested on four different sporadic CAA patients. Two of the patients are Leiden CAA patients and two are Boston CAA patients.

4. Discussion

AD is the most common form of dementia and CAA is a major cause of intracerebral hemorrhage in elderly (Revesz et al., 2002a). Both are progressive neurodegenerative diseases that share Aβ deposition as etiological event: a misbalance in the homeostasis between Aβ production and clearance that promotes accumulation of Aβ in the brain is supposed to represent the earliest event in the disease process in many patients (Blennow et al., 2006; Seubert et al., 1993). Therefore, Aβ is a pathologic hallmark of AD, CAA and related neurodegenerative diseases. Although cerebral accumulation and aggregation of Aβ is the primary neuropathologic feature shared by AD and CAA the two diseases are heterogeneous in Aβ etiology and clinical presentation (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; van Duinen et al., 1987). The availability of diagnostic probes for early detection of cerebral Aβ in living patients which preferably discriminate between vascular and parenchymal aggregates would contribute significantly to the early diagnosis and treatment of this group of disorders.

In this study a panel of immunologic reagents directed against Aβ were examined with the long term objective of developing tools for the early non-invasive differential in vivo imaging of AD and CAA. VHHs have several potential advantages which might allow them to be used for in vivo imaging of neurological disorders. VHHs have a molecular mass of ~15 kDa and because of their small size VHHs show quick tissue penetration, are rapidly cleared from the blood and can have the propensity to cross the BBB. (Zhang et al., 2004; Harmsen et al., 2005; Muruganandam et al., 2002). Furthermore, in animal models, VHHs have shown little immunogenicity and can be produced in a quick en economical manner in microorganisms (Cortez-Retamozo et al., 2002; Frenken et al., 2000; Arbabi-Ghahroudi et al., 2005; Coppieters et al., 2006)

In this study, we compared the performance of VHHs selected from immune- and non-immune libraries in immunohistochemistry. First VHHs were selected from a non-immune and vascular CAA library. This selection from the vascular CAA library resulted in VHHs that only recognize vascular Aβ depositions and fail to recognize parenchymal depositions of Aβ. Because the major component of vascular Aβ in these diseases is Aβ40, high affinity of the VHHs for Aβ40 could explain this selective recognition of vascular beta amyloid (Gravina et al., 1995). We therefore tested affinity preference of our selected VHHs for different Aβ peptides by phage-ELISA. Surprisingly, most VHHs showed highest preference for Aβ1-42. From these results we conclude that although in both vessels and parenchyma progressive cerebral accumulation and aggregation of Aβ is present, Aβ deposition at these two types of structures seems to differ in Aβ epitope availability.

In order to obtain VHHs that preferentially recognize Aβ epitopes that are specific for, or enriched in parenchymal plaques, we immunized a llama with brain parenchyma of a patient with extensive AD pathology. In contrast to the VHHs selected from the vascular library, VHHs selected from this library show high affinity for Aβ present in parenchymal plaques in addition to vascular affinity. The results from the vascular and parenchymal immune libraries suggest that different epitopes are present or exposed in vascular and parenchymal Aβ deposits. While vascular Aβ epitopes recognized by the VHHs are not available in parenchymal Aβ deposition, Aβ epitopes available and recognized in the brain parenchyma are also present in vascular Aβ deposition. This phenomenon may be related to differences in the conformation state of the Aβ present in the vessels and the parenchyma.

In addition to this discrimination between vascular and parenchymal Aβ, VHHs selected from the grey matter AD library recognize parenchymal Aβ selectively in patients with AD pathology but not in HCHWA-D patients. This finding suggests that these VHHs discriminate amyloid plaques from plaques containing (predominantly) non-fibrillar Aβ.

Overall, the VHHs selected from the different libraries showed distinct patterns of specificity when used for immunohistochemistry, with the highest Aβ immune reactivity being observed in the disease condition that was used for immunization. This is consistent with the phage-ELISA data and therefore supporting the presence/availability and recognition by the VHHs of different epitopes present in CAA and AD. Nevertheless, the discriminatory propensity of the VHHs derived from the non-immune and CAA libraries was consistent in sporadic and hereditary CAA.

The formation of highly insoluble fibrils with a β-pleated structure (amyloid) is a common biochemical characteristic shared by proteins with diverse amino acid sequences. This aggregation and fibrillization process is observed in many neurological/neurodegenerative disorders (Westermark et al., 2002). In AD and CAA, Aβ is the major constituent of these aggregates, while in HCHWA-I the amyloid consists mainly of cystatin C (L68Q) (Ghiso et al., 1986). Given the absence of immunohistochemical staining of HCHWA-I protein depositions, we conclude our VHHs are specific for Aβ in its amyloidogenic confirmation. This distinguishes them from some of the recently published antibodies which recognize the amyloid structure independent of its protein composition (Kayed et al., 2007).

Plasma IgGs specific for known toxic Aβ and amyloidogenic non-Aβ species are common in healthy individuals and some of these antibody levels decline with age and AD progression (Britschgi et al., 2009). It has been suggested that these Aβ sequence- or conformation-specific antibodies can prevent or delay Aβ pathology, possibly through a number of different pathways. Although additional studies are required to establish the therapeutic significance of specific Aβ antibodies, a preventive measure toward AD may come from further development of conformation-specific Aβ antibodies such as the VHH described in this study.

In conclusion, we selected sequence specific VHHs against Aβ. Different immunization strategies resulted in the selection of high affinity VHHs specific for different Aβ epitopes. To our knowledge, the VHHs presented here are the first immunologic agents that are capable of discriminating vascular and parenchymal Aβ deposits, though further studies are required to elucidate the basis of this specificity. Additionally, because of the favourable in vivo characteristics of VHHs, these reagents have the potential to serve as tools for in vivo imaging to discriminate between vascular and parenchymal beta amyloid deposition.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Finnbogi R. Thormodsson, PhD, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, for providing cryo-sections of HCHWA-I patients and Ingrid Hegeman-Kleinn for technical assistance. We also would like to thank Kim Retera, PhD, VU Medical Center, Amsterdam, for Biacore analysis support. This work was supported by grants from the IOP Genomics Senter [IGE05005], the National Institutes of Health (NIH AG021084 and AG005134) and by the Centre for Medical Systems Biology within the framework of the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

Footnotes

5.1 Disclosure statement for authors

All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and that the manuscript is not under review at any other publication. Two authors (SMM and CTV) hold a patent on two of the HCAb fragments (ni3A and ni8B) described in this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arbabi-Ghahroudi M, Tanha J, MacKenzie R. Prokaryotic expression of antibodies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:501–519. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-6193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornebroek M, Van Buchem MA, Haan J, Brand R, Lanser JB, de Bruine FT, Roos RA. Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type: better correlation of cognitive deterioration with advancing age than with number of focal lesions or white matter hyperintensities. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1996;10:224–231. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199601040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britschgi M, Olin CE, Johns HT, Takeda-Uchimura Y, LeMieux MC, Rufibach K, Rajadas J, Zhang H, Tomooka B, Robinson WH, Clark CM, Fagan AM, Galasko DR, Holtzman DM, Jutel M, Kaye JA, Lemere CA, Leszek J, Li G, Peskind ER, Quinn JF, Yesavage JA, Ghiso JA, Wyss-Coray T. Neuroprotective natural antibodies to assemblies of amyloidogenic peptides decrease with normal aging and advancing Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;21:12145–1250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904866106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppieters K, Dreier T, Silence K, de Haard H, Lauwereys M, Casteels P, Beirnaert E, Jonckheere H, Van de WC, Staelens L, Hostens J, Revets H, Remaut E, Elewaut D, Rottiers P. Formatted anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha VHH proteins derived from camelids show superior potency and targeting to inflamed joints in a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1856–1866. doi: 10.1002/art.21827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez-Retamozo V, Lauwereys M, Hassanzadeh GG, Gobert M, Conrath K, Muyldermans S, De Baetselier P, Revets H. Efficient tumor targeting by single-domain antibody fragments of camels. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:456–462. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Olichney JM, Thal LJ, Mirra SS, Morris JC, Beekly D, Heyman A. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the CERAD experience, Part XV. Neurology. 1996;46:1592–1596. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenken LG, van der Linden RH, Hermans PW, Bos JW, Ruuls RC, de Geus B, Verrips CT. Isolation of antigen specific llama VHH antibody fragments and their high level secretion by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biotechnol. 2000;78:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(99)00228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiso J, Jensson O, Frangione B. Amyloid fibrils in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis of Icelandic type is a variant of gamma-trace basic protein (cystatin C) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2974–2978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski TJ, Cho HS, Vonsattel JP, Rebeck GW, Greenberg SM. Novel amyloid precursor protein mutation in an Iowa family with dementia and severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:697–705. doi: 10.1002/ana.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos L, Jr, Younkin LH, Suzuki N, Younkin SG. Amyloid beta protein (A beta) in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at A beta 40 or A beta 42(43) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7013–7016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Schlossmacher MG, Hung AY, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Mellon A, Ostaszewski BL, Lieberburg I, Koo EH, Schenk D, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta-peptide is produced by cultured cells during normal metabolism. Nature. 1992;359:322–325. doi: 10.1038/359322a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habicht G, Haupt C, Friedrich RP, Hortschansky P, Sachse C, Meinhardt J, Wieligmann K, Gellermann GP, Brodhun M, Gotz J, Halbhuber KJ, Rocken C, Horn U, Fandrich M. Directed selection of a conformational antibody domain that prevents mature amyloid fibril formation by stabilizing Abeta protofibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19232–19237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703793104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers-Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hamers C, Songa EB, Bendahman N, Hamers R. Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature. 1993;363:446–448. doi: 10.1038/363446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen MM, Van Solt CB, Fijten HP, Van Setten MC. Prolonged in vivo residence times of llama single-domain antibody fragments in pigs by binding to porcine immunoglobulins. Vaccine. 2005;23:4926–4934. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Gregas M, Becker JA, Kinnecom C, Salat DH, Moran EK, Smith EE, Rosand J, Rentz DM, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Dekosky ST, Fischman AJ, Greenberg SM. Imaging of amyloid burden and distribution in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:229–234. doi: 10.1002/ana.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Sarsoza F, Saing T, Cotman CW, Necula M, Margol L, Wu J, Breydo L, Thompson JL, Rasool S, Gurlo T, Butler P, Glabe CG. Fibril specific, conformation dependent antibodies recognize a generic epitope common to amyloid fibrils and fibrillar oligomers that is absent in prefibrillar oligomers. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;26:18. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemier B, de Haard H, Boender P, van Gemen B, Hoogenboom H. Determination of active single chain antibody concentrations in crude periplasmic fractions. J Immunol Methods. 1996;194:201–209. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerwitz Y, Kühn U, Lilie H, Knoth A, Scheuermann T, Friedrich H, Schwarz E, Wahle E. Stimulation of poly(A) polymerase through a direct interaction with the nuclear poly(A) binding protein allosterically regulated by RNA. EMBO J. 2003;22:3705–3714. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muruganandam A, Tanha J, Narang S, Stanimirovic D. Selection of phage-displayed llama single-domain antibodies that transmigrate across human blood-brain barrier endothelium. FASEB J. 2002;16:240–242. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0343fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natte R, Maat-Schieman ML, Haan J, Bornebroek M, Roos RA, van Duinen SG. Dementia in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type is associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy but is independent of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:765–772. doi: 10.1002/ana.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revesz T, Holton JL, Lashley T, Plant G, Rostagno A, Ghiso J, Frangione B. Sporadic and familial cerebral amyloid angiopathies. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:343–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seubert P, Oltersdorf T, Lee MG, Barbour R, Blomquist C, Davis DL, Bryant K, Fritz LC, Galasko D, Thal LJ. Secretion of beta-amyloid precursor protein cleaved at the amino terminus of the beta-amyloid peptide. Nature. 1993;361:260–263. doi: 10.1038/361260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stijlemans B, Conrath K, Cortez-Retamozo V, Van Xong H, Wyns L, Senter P, Revets H, De Baetselier P, Muyldermans S, Magez S. Efficient targeting of conserved cryptic epitopes of infectious agents by single domain antibodies. African trypanosomes as paradigm. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1256–1261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duinen SG, Castano EM, Prelli F, Bots GT, Luyendijk W, Frangione B. Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis in patients of Dutch origin is related to Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:5991–5994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Koningsbruggen S, de Haard H, de Kievit P, Dirks RW, van Remoortere A, Groot AJ, van Engelen BG, den Dunnen JT, Verrips CT, Frants RR, van der Maarel SM. Llama-derived phage display antibodies in the dissection of the human disease oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. J Immunol Methods. 2003;279:149–161. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheesen P, Roussis A, de Haard HJ, Groot AJ, Stam JC, den Dunnen JT, Frants RR, Verkleij AJ, Theo VC, van der Maarel SM. Reliable and controllable antibody fragment selections from Camelid non-immune libraries for target validation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:1307–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Cohen AS, Frangione B, Ikeda S, Masters CL, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Sipe JD. Amyloid fibril protein nomenclature -- 2002. Amyloid. 2002;9:197–200. doi: 10.3109/13506120209114823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Tanha J, Hirama T, Khieu NH, To R, Tong-Sevinc H, Stone E, Brisson JR, MacKenzie CR. Pentamerization of single-domain antibodies from phage libraries: a novel strategy for the rapid generation of high-avidity antibody reagents. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]