Abstract

We examine the role that an exogenous increase in household income due to a government transfer unrelated to household characteristics plays in children's long run outcomes. Children in affected households have higher levels of education in their young adulthood and a lower incidence of criminality for minor offenses. Effects differ by initial household poverty status. An additional $4000 per year for the poorest households increases educational attainment by one year at age 21 and reduces having ever committed a minor crime by 22% at ages 16−17. Our evidence suggests that improved parental quality is a likely mechanism for the change.

1 Introduction

Household conditions and characteristics play an important role in determining the outcomes of children. The strength and nature of that role has been an important research area for social scientists. One characteristic is of special importance for economists –household incomes. Does having more money in the household produce better child outcomes over time? Alternatively, does growing up in poverty produce worse outcomes for children? It is difficult to answer these questions because household incomes are not exogenously given. Income depends crucially on parental characteristics, both observed and unobserved. Therefore, simply observing that children from high (low) income families tend to have positive (negative) educational, income and employment outcomes in young adulthood tells us little about the actual causation. Parents transmit to their genetic offspring some of their innate abilities and the observed correlation between parental incomes and child outcomes later in life may simply re‡ect this intergenerational transfer and not the effect of income per se.

Researchers have sought to overcome this endogeneity problem by using a number of instrumental variables and fixed effects techniques that attempt to isolate the difference in household incomes that are not due to parental characteristics or ability. Using father's union and occupational status as instruments for income, Shea (2000) finds that income has no effect on child outcomes while Chevalier et al. (2005) finds that permanent income matters in children's educational attainment. Maurin (2002) uses grandparent socioeconomic status as a predictor of parental incomes which is then used to explain a child's performance in early education. He finds that a child is much less likely to be held back in school the higher the household income. Loken (2007) uses the Norwegian oil boom of the 1970's and 1980's, which only affected a few regions of the country, as an instrument for increases in household income that is unrelated to parental characteristics. She finds that there is no effect of family income on child educational attainment. For these instruments to be valid, we must assume that there is no choice involved in union or occupational status or selection in the job loss instruments. Alternatively, we must assume that there is no transmission of abilities across generations for the grandparent socioeconomic instrument to be valid. Finally, in the oil boom scenario we must assume no endogenous movement across regions but also that all industries within the affected regions were not differentially affected.

Other researchers have used more permanent income measures such as household assets. Mayer (1997) uses household assets and child support payments as measures of household income (these are taken to be less closely related to parental characteristics) and she finds that income has a positive and significant effect on educational attainment and wages. Blau (1999) uses child fixed effects in the National Longitudinal Study of Youth data and finds that parental income (at least the transitory component) does not affect child test scores. Sacerdote (2007) finds that parental income matters less than parental education for young adult educational, income and health outcomes for Korean-American adoptees in his data; this research design is particularly useful, however, the obvious drawback here is that there is selection with regard to families willing to adopt children. Households that adopt children are not representative of the population at large.

While previous research has found conflicting results with regard to the effect of household income on the young adult outcomes of household children, none of those studies have been able to identify a truly exogenous income change at the household level. Recent work by Dahl and Lochner (2005) using panel data and changes in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the US have shown that reading and math scores improved in households with increased earnings - especially for most disadvantaged households. Oreopoulos et al. (2005) find in their intergenerational data that children who come from households where fathers were displaced from their jobs have on average 9% lower earnings than children whose fathers were not displaced in childhood. Once again they find the effect to be driven by the most disadvantaged households - this will hold generally in our data as well. Our empirical strategy most closely match those of Duflo (2003). In her paper, Duflo examines the effect of pension extension to the black South Africans by gender on the anthropometric status of grandchildren in these households. We find, similar to Duflo, that an exogenous increase in household income matters for child outcomes and that there is a gendered effect - women have a large effect on child educational attainment.

Our approach attempts to overcome the standard household income endogeneity problem in a direct manner - we observe households where incomes are increased exogenously and permanently through a governmental transfer program without regard to parental human capital, ability or other household characteristics. In our study, we follow children that reside in households with and without exogenously increased incomes. The children are sampled in three age cohorts. The youngest children reside as minors in households with higher incomes for a longer period of time than the oldest children in this study. We compare educational attainment and criminality outcomes from the youngest age cohort to the oldest age cohort to determine the effect of residing in a household with exogenously higher incomes. The children from households without additional household income serve as a control for any changes in local labor market opportunities that may have arisen between the age cohorts.

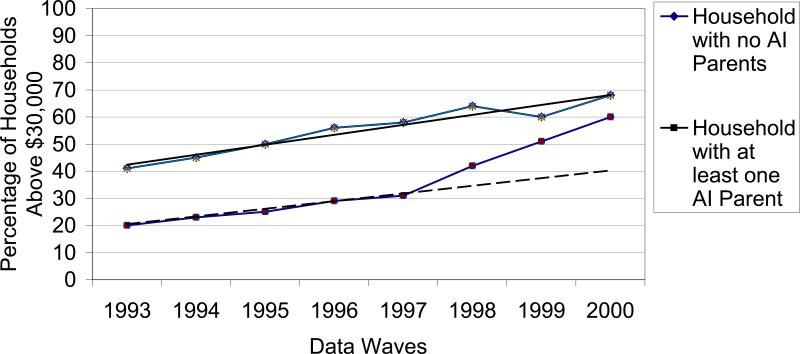

Our study uses data from the Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth (GSMS). In this longitudinal study of child mental health in rural North Carolina, both American Indian and non-Indian children were sampled. Halfway through the data collection, a casino opened on the Eastern Cherokee reservation. A portion of the profits from this new business operation is distributed every six months on an equalized, per capita basis to all adult tribal members regardless of employment status, income or other household characteristics. No choice is involved here - individuals are eligible based on pre-existing American Indian status. Therefore, we can observe the treatment effect on an entire distribution of household types. Non-Indian households are not eligible for these cash disbursements. Figure 1 provides a clear depiction of the change in household incomes over the first eight survey waves of our study. A marked increase is noted in the number of households with incomes above $30,000 for the treatment (American Indian) households after the disbursement of casino payments in 1997.1 No long-run change is observed for non-Indians households.

Figure 1.

Household Income By American Indian Parent Status in Waves 1−8

On the one hand American Indians are a particular group in the United States, with real per capita income of $8000 in the 2000 US Census and poverty rates in excess of 37% (compared to the US average of $21,000 and a 9% poverty rate). Decades of failed policies have plagued American Indian reservations from land reform policies to natural resource extraction and business development.2 In this regard, the advent of casino operations has been hailed as a viable means of creating prolonged economic development. On the other hand, this particular American Indian reservation is fairly well integrated into the local regional economy of western North Carolina. There is only about a $10,000 difference in average pre-casino operations household incomes between the American Indian households and non-Indian households in our survey; this is still a large number but smaller than national averages would suggest. Additionally, the reservation is not particularly isolated nor large.3 Our research question is a general one that is of interest for other high poverty groups in the US - how effective are anti-poverty cash-transfer programs in improving the outcomes of household children? While the particular circumstances associated with the casino are unusual; the government transfer payment is not. This study examines the effect of a cash transfer on children from poor American Indian households and these findings could also be instructive for other poor semi-rural communities in the US. Our research design allows us to evaluate the effect along an entire distribution of household incomes - a rarity in these sorts of studies.

We find that children who reside the longest in households with exogenously increased incomes tend to do better later in life on several outcome measures. The children in these households are more likely to have graduated from high school by age 19 as compared to the children from untreated households; by age 21 the treated children from the poorest households have an additional year of schooling.4 A rough estimate indicates that an average of $4000 additional household income for the poorest families results in an additional year of education for the child from a treated household. Additionally, we find, using administrative records on criminal arrests, that these same children have statistically significantly lower incidence of criminal behavior for minor offenses; the additional household income reduces ever having committed a minor crime by 22% at ages 16−17 for these children from treated households. These children also self-report that they have a lower probability of having dealt drugs than children from households unaffected by the additional income.

As expected, the poorest households in the survey experience the largest gains in terms of child outcomes. Separating the data according to prior poverty status, we find that many of these results are driven by the poorer households. The findings also indicate that mothers who receive the exogenous increase in incomes affect the educational outcomes, while fathers who receive the income affect the child's criminal behavior.5

There are numerous mechanisms that may translate higher household incomes into better child outcomes. We explore two potential mechanism: parental quality and parental time. The additional income may allow the poorer households to substitute away from full-time employment towards part-time employment thus allowing for more child care. This does not appear to happen in our data; parents do not reduce their working time. On the other hand, we find that parental interactions and experience with the children in the affected households tends to improve dramatically. Both child and parent report improved behavioral effects and parent-child interactions relative to unaffected households. We observe that parent behavior, similar to those of the child, tend to improve with regard to criminality.6 Previous research has found a direct relationship between poverty and parenting ability (McLeod, 1993; Sampson, 1994; Ennis, 2000) and we confirm this result in our research. There is at least some indication that one of the mechanisms responsible for translating higher household incomes into better child outcomes is through increased parental quality; while parenting time does not appear to have been an important causal factor.

The next section describes the data from the Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth and our empirical methods. Section III provides our estimation results. We explore some potential mechanisms which may play a role in translating increased incomes into better child outcomes in Section IV. Section V concludes.

2 The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth, Empirical Methods and Data Description

The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth (GSMS) is a longitudinal survey of 1420 children aged 9, 11 and 13 years at the survey intake that were recruited from 11 counties in western North Carolina. The children were selected from a population of approximately 20,000 school-aged children using an accelerated cohort design.7 American Indian children from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians were over sampled for this data collection effort, survey weights are used in the child outcome regressions that follow. The federal reservation is situated in two of the 11 counties within the study. The initial survey contained 350 Indian children and 1070 non-Indian children. Proportional weights were assigned according to the probability of selection into the study; therefore, the data is representative of the school-aged population of children in this region. Attrition and non-response rates were found to be equal across ethnic and income groups.

The survey began in 1993 and has followed these three cohorts of children annually up to the age of 16 and then re-interviewed them at ages 19 and 21.8 Additional survey waves are scheduled for these children when they turn 24 and 25 years old. Both parents and children were interviewed separately up until the child was 16 years old; interviews after that were only conducted with the child alone.

After the fourth wave of the study, a casino was opened on the Eastern Cherokee reservation. The casino is owned and operated by the tribal government. A portion of the profits are distributed on a per capita basis to all adult tribal members.9 Disbursements are made every six months and have occurred since 1996. The average annual amount per person has been approximately $4000. This income is subject to the federal income tax requirements.

2.1 Empirical Specifications

2.1.1 Difference-in-Difference Regression

We compare young adult outcomes for children that resided for a total of six years as minors in households with increased incomes to children who resided for just two years as minors in households with exogenously increased incomes. We employ a difference-in-difference methodology. This specification allows us to compare the effect of four additional years of higher household incomes on young adult outcomes for these children. The two youngest age cohort variables (Age 9 and Age 11 at survey intake) function as the “after-treatment” cases and the oldest age cohort (Age 13 at survey intake) functions as the “before-treatment” case. We focus explicitly on the effect of the per capita transfer on children's outcomes. An examination of the effect of the treatment on household income indicates that almost the entirety of the additional cash transfer shows up as additional household income in each survey wave.10

The size of the exogenous increase in household incomes can take on two different values depending upon the number of American Indian parents in each household. It is possible for there to be 0,1 or 2 American Indian parents in each household.11 Clearly households with two American Indian parents will have double the amount of exogenous income than households with only a single American Indian parent. Households without an American Indian parent serve as a control household. We treat the number of parents as a continuous variable and we therefore have two interaction variables which are of interest. The equation below details the specification:

| (1) |

In the equation above, Y is the outcome variable of interest for the child at ages 19 or 21. We will examine educational attainment, high school completion variables and criminal arrests at various ages (16−21). In the equation above, the Age9 and Age11 variables indicate whether or not the child is drawn from the initially age 9 or age 11 cohorts respectively –the age 13 cohort is the omitted category in this regression. The variable NumParents indicates the number of American Indian parents in that child's household. The two coefficients of interest for this research are γ1and γ2, which measure the effect of receiving the casino disbursements and being in either the age 9 or age 11 cohorts relative to the 13 year old cohort and not receiving any household casino disbursements. The vector X controls household conditions prior to the opening of the casino and includes household poverty status, average household income over the four years, the sex of the child, the race of the child and education levels of both parents. All results presented for the child outcomes are robust to inclusion of the number of siblings in the household. Survey weights are employed in all of these difference in difference regressions. In the online Appendix I we provide robustness tests, where possible, for the outcome variables described above. Additionally, robustness tests are provided for changes in parental outcomes as well.

Identification of equation 1 relies on the fact that the different age cohorts of children were randomly sampled within American Indian and non-Indian groupings. The next section provides evidence for this and also indicates that the two groups of households (American Indian and non-Indian) faced similar conditions in the labor market and with regard to social conditions. It is also important to note that there were no new health or educational programs which were created immediately after the advent of casino disbursements by the tribal government. This is important in establishing the fact that time variant characteristics that were related only to American Indians (such as tribally-funded anti-crime programs or tutoring programs) are not the causal factor here. In later years new programs have been developed, but for the crucial period in which these children were minors in their parents’ households, there is little evidence of new programs. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the revenues from the casino operations were, at least in the short run, spent on per capita disbursements to the tribally-enrolled membership. Spending on large scale construction (such as a new community gym, diabetes center and other affiliated offices) and programs did not occur until 2001−2002. Therefore, the children in this study were not minors when these new programs and facilities were operational and were not likely to have been affected at all. Schools on the reservation were constructed in the 1970s and a new school, which is not yet operational, is set to open in 2009.

Another point worth mentioning is that the effect of this new industry, casino operations, may have a rather large effect on the demand for labor in the local labor market. This increase in demand may affect the employment opportunities and wages in the region. In fact, this change in labor demand may be directly driving all of the observed results and the actual cash transfer program may be inconsequential. There are a number of reasons why that probably does not hold. First, we know whether parents are employed at all survey waves; there does not appear to be a dramatic increase in parental employment after the casino begins operations. Second, we would have to assume that the labor supply in this region was relatively inelastic in order to get large increases in wages. Others have shown (Evans and Topoleski, 2002) that labor supply in these communities are highly elastic and there has been large in-migration when casinos open up on American Indian reservations between 1990 and 2000. Therefore, we do not expect there to be a large change in wages even with a large increase in labor demand for the region. There are several rather large towns and cities in the region and this argues against a very inelastic supply of labor.

Finally, we use global positioning system data (GPS) to compute a distance measure which serves as proxy for other non-cash transfer related effects of the casino operations on households. The average household is 32 miles (median is 36 miles) away from the casino, with a minimum distance of 5 miles and a maximum distance of 75 miles. We find that inclusion of this measure (which is available for all survey households) and an interaction variable with treatment households does not diminish the effects reported in later tables. 12

2.1.2 Fixed-Effects Panel Regression

Given the panel nature of the data, we are also able to utilize individual fixed effects for one of the outcome variables –child's school attendance. This educational measure is meaningful at various points throughout the child's life, not just at young adulthood as is the case with the other educational attainment measures. Therefore, we employ a fixed effects regression for the number of days a child is present at school in the last three months prior to the interview. The regression is given of the form:

| (2) |

In this regression, αi is the individual fixed effect and X is the vector of control variables, including whether the individual child, i, belongs to a household that is eligible for casino payments. This indicator variable is always zero for households without American Indian parents; for households with American Indian parents the variable is zero for the first four survey waves and then take the value of one thereafter. We employ a similar model when testing for changes in parental employment status, arrest, and relationship with their children in the second half of the paper which investigates the mechanisms through which additional household income affects young adult child outcomes.

2.2 Data Description

2.2.1 Data Means

Table 1 provides the means for the data used in this analysis by the type of household. The first panel provides the variables used primarily in the difference in difference regressions, while the second panel provides the data used in the fixed-effects regressions. In panel A, the first set of columns provides the means for the households with at least one American Indian parent and the second panel contains the means for households that do not have any American Indian parents.

Table 1.

Mean Values for Variables for all Survey Waves, cont.

| Panel A: Difference in Difference Regressions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| At least one AI Parent Household |

No AI Parent Household |

||

| Variable | Mean | Mean | T-Statistics for Difference in Group Means |

| Education Variables | |||

| Years of Education | 11.21 | 11.96 | −4.10 |

| High School Graduation Probability at age 19 | 0.62 | 0.69 | −2.12 |

| Received a GED or Graduated from High School at age 19 | 0.76 | 0.82 | −2.26 |

| Age, Parents and Interaction Variables | |||

| Age Cohort Initially 9 Year Olds | 0.39 | 0.35 | 1.26 |

| Age Cohort Initially 11 Year Olds | 0.33 | 0.34 | −0.51 |

| Age Cohort Initially 13 Year Olds | ref. | ref. | |

| Number of American Indian Parents | 1.34 | 0.00 | 20.63 |

| Interaction Age 9 Cohort × Number of American Indian Parents | 0.52 | 0.00 | 17.98 |

| Interaction Age 11 Cohort × Number of American Indian Parents | 0.45 | 0.00 | 79.58 |

| Household Characteristics | |||

| Male Child Indicator | 0.52 | 0.53 | −0.29 |

| Mother Has a High School Degree/GED | 0.36 | 0.29 | 2.31 |

| Father Has a High School Degree/GED | 0.21 | 0.17 | 1.53 |

| 0.35 | 0.49 | −4.06 | |

| Mother Has More than a High School Degree | |||

| Father Has More than a High School Degree | 0.2 | 0.31 | −3.51 |

| Average Years Household in Poverty over initial 3 years | 1.40 | 0.66 | 9.60 |

| Average Household Income (by category) for first 3 years | 4.58 | 6.65 | −8.79 |

| Average Household Income (in dollars using mid-point of each category) for first 3 years | 20,919 | 30,377 | −3.96 |

| Crime Variables | |||

| Any Crime Ages 16−17 | 0.10 | 0.14 | −1.72 |

| Any Crime Ages 18−19 | 0.17 | 0.22 | −1.81 |

| Any Crime Ages 20−21 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.28 |

| Any Minor Crime by Age 21 | 0.25 | 0.29 | −1.10 |

| Any Moderate Crime by Age 21 | 0.09 | 0.14 | −1.79 |

| Any Violent Crime by Age 21 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.86 |

| Ever Dealt Drugs by Age 21 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.47 |

| Panel B: Fixed Effect Regressions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one |

No AI |

|||

| Variable | Mean | Mean | T-Statistics for Difference in Group Means | Total Observations |

| Education Variable | ||||

| Days Present at School in Last Quarter | 39.64 | 39.15 | 1.27 | 3317 |

| Mother's Characteristics | ||||

| Labor Force Participation Rate | 0.88 | 0.87 | 1.14 | 6780 |

| Labor Force Attachment | 3.24 | 3.21 | 0.59 | 6780 |

| Arrest Status | 0.12 | 0.06 | 7.51 | 5333 |

| Supervision of Child | 1.81 | 1.79 | 0.89 | 5758 |

| Activities spent with Child | 1.87 | 1.88 | −1.15 | 6673 |

| Father's Characteristics | ||||

| Labor Force Participation Rate | 0.90 | 0.93 | −3.95 | 4161 |

| Labor Force Attachment | 3.41 | 3.66 | 6.61 | 4161 |

| Arrest Status | 0.27 | 0.13 | 9.18 | 3309 |

| Supervision of Child | 1.11 | 1.12 | −0.27 | 5758 |

| Activities spent with Child | 1.90 | 1.92 | −1.23 | 3829 |

Note: Total sample size is 1060 observations for all three age cohorts when they are 21 years of age,

Note: Bold Figures are statistically significant at the 5% significance level.

Note: Sample size differs across these variables due to missing information.

Note: Bold Figures are statistically significant at the 5% significance level.

Educational Variables

It is worth noting that children from households with at least one American Indian parent have statistically significantly different educational attainment on average as compared to children from households with no American Indian parents.13 On all measures, children from the first type of household have lower recorded educational attainment or completion.

Age Cohorts

The next group of variables indicates the distribution among the different age cohorts and the number of American Indian parents. There is a slightly higher proportion of children found in the 9 year old age cohort for the American Indian parent household than for the non-Indian parent household –but this difference is not statistically significant. The second age cohort is much closer in number distribution between the two types of households. The number of American Indian parents and the interaction terms differ between the two household types by design.

Household Characteristics

The third set of variables provides a look at the household conditions prior to the opening of the casino for both groups of children. There are level differences between all of the initial household conditions except for the gender distribution for children from both types of households. The parental education variables, unlike the education measures for the child, are given in categories not in years. It appears that parents from households with at least one American Indian parent tend to be overrepresented in the high school degree category as compared to households without American Indian parents. Additionally, households without American Indian parents tend to be overrepresented in the more than high school education category. The omitted category is less than a high school or GED degree; all categories are mutually exclusive for the parental education variables. Finally, the last two variables provide insight into the economic conditions of the households. On average, households with at least one American Indian parent have spent at least one year in poverty in the first three years of the study while the figure is 0.66 years for the households with no American Indian parents. Income is also given in categories and the value of 4.58 corresponds to an annual income between $15,001 and $20,000. For households with no American Indian parents, the average household income value of 6.65 falls in the $25,001 to $30,000 annual income category. Using the midpoint of income categories give an average household income of about $20,000 for American Indian households and an average household income of about $30,000 for non-Indian households in our survey.

Criminality Measures

The final set of variables in this panel provide the criminal activity of the sample children. These data are gathered independently from the GSMS data. Searches of public databases in the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts produced these data. All counties in North Carolina are covered by these data including arrests made on the American Indian reservation. Arrests after the 16th birthday fall under the jurisdiction of the adult criminal justice system. Arrest records were found for juvenile arrests with the permission of the juvenile court judges. We have classified the arrest records into three broad categories: minor arrests which includes arrests for disorderly conduct, trespassing and shoplifting; moderate arrests which are primarily property crimes that do not involve serious harm to a person such as simple assault, felony larceny and drug-related offenses; violent arrests which include sexual assault, armed robbery and assault with deadly weapons. The first set of variables reports whether a child has committed any crime in the years indicated. The categories are not cumulative and are independent of one another. Therefore, we see that a child from a household with at least one American Indian parent had a 10 percent chance of committing any type of crime (minor, moderate, violent) between the ages 16−17. A child from an American Indian household had a 17% chance of committing any type of crime between the ages 18−19. The next set of variables measures whether a child has committed any crime by age 21 by arrest category. The first variable indicates that a child from a household with at least one American Indian parent had a 25 percent chance of having committed a minor crime by age 21, while the same figure for a household with no American Indian parents was 29 percent. Interestingly, children from American Indian households are less likely to have been arrested for all crimes across the board and statistically significantly less (at the 10% level) for moderate crimes by age 21. The final variable is found within the GSMS survey and indicates the child's self-reported drug dealing behavior at each survey wave. The mean of this variable indicates that 6% of children from both types of household report ever having dealt drugs.

Fixed Effects Data

Panel B of Table 1 provides the data used primarily in the fixedeffects regressions for changes in parental behavior. The first variable gives the number of days the child was present in school in the last quarter. This question is asked at every survey wave while the child is less than 18 years old. There is no statistically significant difference between children in the two types of households.

Panel Data Characteristics for Parents

The next set of variables provides characteristics of the mother at each stage over the survey time period. The first variable is coded 1 for individuals who are in the labor force (working outside of the home) and 0 otherwise. There is no statistically significant difference between the labor force participation of mothers by household type. Labor force attachment is a categorical variable which measures (on a scale of 0 to 4) an individual's degree of involvement in the labor force: a zero indicates no work whatsoever (student, retired or disabled), one indicates work only in the home, two indicates currently unemployed, three indicates part-time employment, while four indicates full time employment. For mothers it does not appear that there is any difference in the attachment to the labor force. For mothers who are working, they tend to be less than full-time employed. Arrest status is simply an indicator variable for whether the mother was arrested since the last survey wave. Once again there is a statistically significant difference here with mothers from non-American Indian households slightly more likely to have been arrested.

The child supervision variable measures the adequacy of parental supervision of their child. There are three options here: a zero indicates that the parent does not have adequate control or knowledge of the child's whereabouts at least fifty percent of the time or more; a one indicates that the parent does not have adequate control or knowledge of the child's whereabouts at least once a week; while a value of two indicates that the parent has age appropriate supervision or control over the child. The average value for both groups of households is approximately one which indicates on average for all survey waves that parents did not know where their children were at least once in the previous reference week. The final variable is a measure of the percentage of parent-child activities and interactions that are categorized as enjoyable by the child at each survey wave; the previous measure of parental supervision was only asked of the parents. The three options possible here are: a zero indicates that less than 25 % of all activities with the parent are enjoyable to the child; a value of one indicates that between 25% and 74% of all activities are a source of tension, worry or disinterest to the child; a value of two indicates that at least 75% of all activities are enjoyable. We observe that there is no statistically significant difference between household types for these last two variables. The results for fathers are presented in the next section. There is a statistically significant difference for fathers by type of household for labor force participation, labor force attachment, and arrest status.

2.2.2 Differences Across Age Cohorts by Observed Characteristics

We use the oldest age cohort of children as the control group for the two younger age cohorts. In order for this to be a valid strategy, the different age cohorts must be reasonably similar to one another on average. We would assume this to be the case as the survey design employed a randomized selection process. Nevertheless, we present evidence of this fact using observable characteristics of the childrens’ households. Table 2 presents a comparison of these initial household characteristics by age cohort for each of the two types of households. This table provides information on the suitability of the third age cohorts to serve as controls for the two other age cohorts in this study. In this table, t-statistics are presented for a test of a mean difference between the indicated age cohorts for a given variable. In the top panel of Table 2 we show the differences in age cohorts for households that have no American Indian parents. There are statistically significant differences in the number of American Indian children in these households for cohorts 2 and 3 (age 11 and age 13 initially) and cohorts 1 and 3 (age 9 and age 13 initially). The difference is driven by the relatively large amount of American Indian children in the third age cohort (7%). There is no difference in the gender distribution for any of the three cohorts. We observe little difference in education levels for the parents by age cohorts. We do find statistically significant differences for household income levels for cohorts 1 and 2 as well as for cohorts 1 and 3. The mean difference between income categories is very small here 0.7 and 0.6 for each respectively. Each income category represents a step of $5,000 each. Therefore, the difference represented here on average is between $3,000 − $3,500 per year.

Table 2.

T-Scores of Mean Differences by Age Cohort and American Indian Parent Status

| Households with No American Indian Parent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference Between Cohort 1 and 2 | Difference Between Cohort 2 and 3 | Difference Between Cohort 1 and 3 | |

| Number of American Indian Parents | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| American Indian Indicator | −1.43 | −2.00 | −3.35 |

| Male Child Indicator | −0.93 | 1.84 | 0.95 |

| Mother Has a High School Degree/GED | 0.81 | −0.25 | 0.52 |

| Father Has a High School Degree/GED | <−0.001 | 1.49 | 1.50 |

| Mother Has More than a High School Degree | −1.51 | 1.21 | −0.23 |

| Father Has More than a High School Degree | −0.83 | 0.49 | −0.30 |

| Household Income | −2.47 | 0.36 | −2.04 |

| Households with at least one American Indian Parent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference Between Cohort 1 and 2 | Difference Between Cohort 2 and 3 | Difference Between Cohort 1 and 3 | |

| Number of American Indian Parents | −0.49 | 1.29 | 0.84 |

| American Indian Indicator | −1.89 | 1.86 | 0.04 |

| Male Child Indicator | −0.56 | 0.05 | −0.46 |

| Mother Has a High School Degree/GED | 1.06 | −0.05 | 0.93 |

| Father Has a High School Degree/GED | 1.00 | −1.66 | −0.65 |

| Mother Has More than a High School Degree | −0.63 | 0.45 | −0.14 |

| Father Has More than a High School Degree | −0.30 | 0.62 | 0.34 |

| Household Income | 0.34 | −1.60 | −1.29 |

Note: Each cell provides t-statistics for a test of difference in means

Note: Bold Figures are statistically significant at the 5% significance level.

Note: Each cell provides t-statistics for a test of difference in means

Note: Bold Figures are statistically significant at the 5% significance level.

The bottom part of Table 2 provides a similar analysis for the households with at least one American Indian parent. There appears to be very little differences between these age cohorts. In sum, it appears that the data are reasonably similar across age cohorts for both types of households. While there are some statistically significant differences, the magnitude of these differences for most variables is in fact quite small.

2.2.3 Time Trends

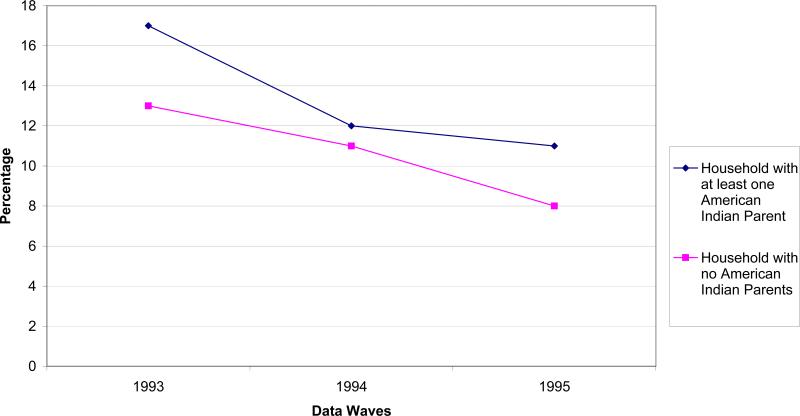

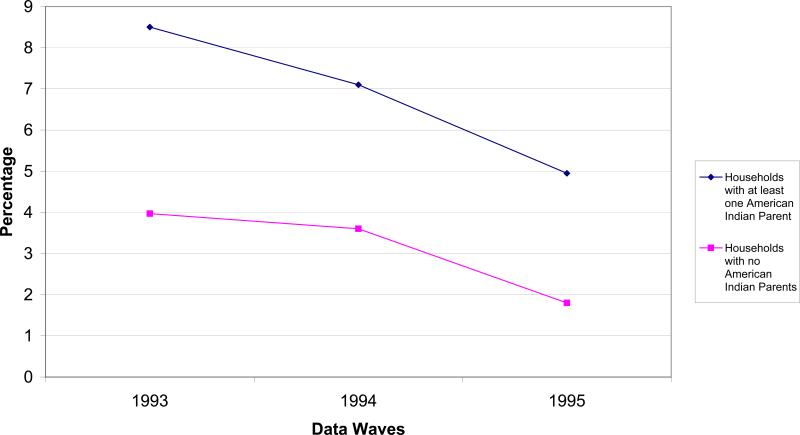

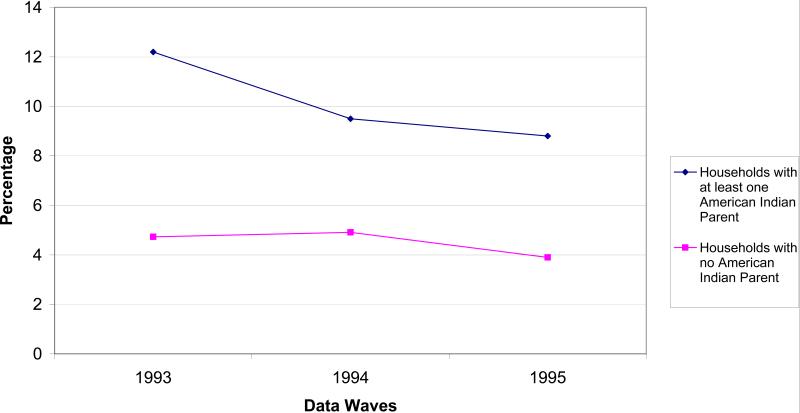

It is extremely important in a difference-in-difference frame work that we control for any changes that may have occurred in these communities unrelated to the casino disbursements over time. Children from households that are not eligible for casino disbursements control allow us to control for these changes. We show in the following figures that the two types of households (those with and without American Indian parents) are affected similarly by the general macroeconomic and social conditions in this region. While in general the American Indian households tend to perform slightly worse on most measures, the rate of change over time is indistinguishable from that of non-American Indian households in the region. Absolute differences in average conditions or characteristics are permissible in the differencein-difference framework as long as the rate of change prior to the intervention was stable across both groups. We provide some evidence on the similarity of the time trends of the two types of households in the time period prior to the opening of the casino. It is not, of course, possible to show how the unobserved heterogeneity effect evolves over time for the two types of households; however we do show that the households have similar trends in a number of dimensions. Figure 1 provides the trend in household incomes for the two types of households and we have already noted that there is a significant difference after the opening of the casino. However, prior to the opening of the casino, the growth in the percentage of households with incomes greater than $30,000 was similar between the two groups; a simple test comparing the two trend lines results in p-value of 0.178 rejecting the hypothesis that the two trends are different over these three time periods. Figures 2 and 3 show the changes in the unemployment rate for mothers and fathers respectively. Both figures indicate that unemployment was generally decreasing and consistent for both household types; the p-values for a test of whether the trends in each figure are different are 0.78 and 0.176 respectively which once again rejects the null hypothesis that the trends between groups are different over these survey waves. Figure 4 shows the difference in reported incidence of alcohol or drug abuse problems for the father as reported by the mother.14 The distance between the two time trends decreases slightly between periods 1 and 2, but then is a relatively constant distance between waves 2 and 3; the p-value for a test of equality of trends is 0.39 which again rejects the hypothesis that the two trends differ.

Figure 2.

Mother's Unemployment Incidence by Waves 1−3

Figure 3.

Father's Unemployment Incidence by Waves 1−3

Figure 4.

Father's Reported Drug and Alcohol Incidence by Data Waves as Reported by Mother

Taken together these figures indicate that the two types of households, while differing in levels, appear to be equally affected by the same social conditions, macroeconomic conditions and labor market experiences. The Eastern Cherokee reservation is located in the middle of the eleven counties surveyed in this research. There is little evidence to support that the two household types are affected differently by changes at the local level in the period prior to the casino opening.

Additionally, testing between the nature of household types across time, it appears that there is no statistically significant difference in the composition of households across time. In the online Appendix Table II we provide t-tests of differences in marital status for the household types after the casino begins operations. The additional casino funds does not appear to affect the marital status of couples included in this data. This finding indicates that the casino payments are not creating incentives for the dissolution or the creation of new partnerships which may directly affect the young adult outcome of children.

3 The Effects of Exogenous Change in Income on Young Adult Educational Attainment and Criminal Behavior

In this section, we present the results from the difference-in-difference regression described in equation 1 and the fixed-effects regression described in equation 2. All of the results control for robust standard errors or clustered standard errors at the individual level in the fixedeffects regressions and employ survey weights. Where the outcome variables are indicator variables, we use a probit specification and report marginal coefficients. For continuous outcome variables, such as years of education, we use a simple ordinary least squares regression for our analysis.15

3.1 Education Outcome Variables

Table 3 presents the results from regressions for the educational outcome variables. The first column presents the regression of years of completed child's education at age 21 on the level and interaction variables previously described. The two interaction variables presented in the first two rows indicate that there is a positive, but not statistically significant, effect of residing in a household with exogenously increased incomes for six or four years relative to just two years. The coefficient on the first interaction variable indicates that children who reside in treatment households and come from the youngest age cohort have on average about four months more education at age 21 than their untreated counterparts - although this coefficient is not statistically significant. The other variables of interest in the regression are the parental education variables: the more than high school education variables are positive and statistically significant for both parents. The average household income in the first three survey waves variable is also positive and statistically significant in this and the other two regressions as well. Column two presents the probability of a child being a high school graduate by age 19. The marginal coefficient on the first interaction variable indicates that the effect of having four more years of exogenously increased household income increases a child's probability of finishing high school by age 19 by almost 15 percent. The second interaction coefficient is positive, but smaller in absolute magnitude and not statistically significant. The third column outcome variable measures whether an individual has a high school diploma or a general equivalency degree. The first interaction coefficient is once again positive but not statistically significant at conventional levels. It is important to note that the American Indian children had an incentive to finish high school by age 18 as they became eligible for payment of the semi-annual casino payments themselves; otherwise they would have to wait until age 21. In that sense, we should interpret the changes in high school graduation rates as more similar to an outcome from a traditional conditional cash transfer program (Schultz, 2000; Behrman et al., 2005). After age 21, however, all of these American Indian children receive the transfers regardless of high school completion.

Table 3.

Effect of Cash Transfer on Children's Educational Achievement

| Years of Education, Age 21 |

Probability of HS Grad, Age 19 |

Prob of HS Grad/GED, Age 19 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Coeff. | Marg. Eff. | Marg. Eff. |

| Interaction 1: Age Cohort 1 × Number of American Indian Parents | 0.379 | 0.156** | 0.086 |

| (0.447) | (0.073) | (0.054) | |

| Interaction 2: Age Cohort 2 × Number of American Indian Parents | 0.117 | 0.042 | 0.033 |

| (0.304) | (0.066) | (0.044) | |

| Age Cohort 1 (9 yo) | −0.269 | −0.025 | −0.019 |

| (0.294) | (0.060) | (0.0457) | |

| Age Cohort 2 (11 yo) | 0.072 | −0.010 | −0.016 |

| (0.275) | (0.055) | (0.041) | |

| Number of American Indian Parents in Household | −0.503 | −0.156 | −0.131*** |

| (0.350) | (0.068) | (0.047) | |

| American Indian | 0.003 | 0.081 | 0.075 |

| (0.472) | (0.063) | (0.038) | |

| Sex | −0.639*** | −0.123*** | −0.081*** |

| (0.227) | (0.043) | (0.033) | |

| Mother Has a High School Degree/GED | 0.557 | 0.103* | 0.079** |

| (0.399) | (0.051) | (0.034) | |

| Father Has a High School Degree/GED | −0.164 | 0.001 | 0.026 |

| (0.396) | (0.067) | (0.044) | |

| Mother Has More than a High School Degree | 0.924** | 0.117** | 0.129*** |

| (0.367) | (0.058) | (0.045) | |

| Father Has More than a High School Degree | 0.757** | 0.053 | 0.051 |

| (0.306) | (0.056) | (0.040) | |

| Household Previously in Poverty Indicator Variable | −0.120 | −0.045 | −0.026 |

| (0.174) | (0.028) | (0.019) | |

| Average Household Income in First Three Survey Waves | 0.214** | 0.031*** | 0.022*** |

| (0.048) | (0.010) | (0.007) | |

| Constant | 10.554 | ||

| |

(0.532) |

|

|

| Observations | 1045 | 1060 | 1060 |

| Wald Chi-Squared (15) | 24.53 | 88.01 | 96.22 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2577 | 0.157 | 0.172 |

Note:

indicates coefficient statistically significant at the 1% level,

at the 5% level

at the 10% level.

Note: Years of Education regressions are ordinary least squares, the next two regressions are probit regressions with marginal coefficients calculated.

Note: Robust standard errors are given in parenthesis below the estimated coefficients.

3.2 Educational Outcome by Previous Poverty Status, Child Gender and Parental Gender

We now investigate whether the exogenous increase in incomes has differing impact by the prior poverty status of households. The first four columns of Table 4 presents the same analysis as Table 3, except that the sample has been divided according to whether the household was ever previously in poverty prior to casino operation.16 We find in the first two regressions, for households previously in poverty, that the coefficient on the first interaction term is always statistically significant at the 5 % level and larger in magnitude than in Table 3. The coefficient for the interaction variable for the years of education regression triples in size and implies that the treatment of four additional years of exogenously increased income increases educational attainment at age 21 by a full year (1.1 years).17 The first interaction variable coefficient for the high school graduation regression increases in magnitude and is highly statistically significant. The next two columns present the results from the subsample of households that were never previously in poverty in the first three survey waves. None of the coefficients on the interaction variables are statistically significant. These results explain the results for the full sample which yielded statistically insignificant results for the years of education regression –the additional household income does not have a noticeable effect in households not previously in poverty.18

Table 4.

Effect of Cash Transfer on Educational Achievement by Previous Household Poverty Status, Child Gender and Parental Gender

| Household Previously in Poverty |

Household Not Previously in Poverty |

Male Child |

Female Child |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Education, Age 21 |

Probability of HS Grad, Age 19 |

Years of Education, Age 21 |

Probability of HS Grad, Age 19 |

Years of Education, Age 21 |

Probability of HS Grad, Age 19 |

Years of Education, Age 21 |

Probability of HS Grad, Age 19 |

Years of Education, Age 21 |

Probability of HS Grad, Age 19 |

|

| Independent Variables | Coeff. | Coeff. | Marg. Eff. | Marg. Eff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Marg. Eff. | Marg. Eff. | Coeff. | Marg. Eff. |

| Interaction 1: Age Cohort 1 × Number of American Indian Parents | 1.127*** | 0.391*** | −0.166 | 0.129 | 0.586 | 0.164 | 0.809 | 0.196*** | ||

| (0.449) | (0.135) | (0.722) | (0.085) | (0.421) | (0.100) | (0.597) | (0.086) | |||

| Interaction 2: Age Cohort 2 × Number of American Indian Parents | 0.451 | 0.298** | −0.058 | 0.011 | 0.470 | 0.053 | 0.100 | 0.047 | ||

| (0.436) | (0.140) | (0.422) | (0.075) | (0.384) | (0.099) | (0.448) | (0.082) | |||

| Interaction 1: Age Cohort 1 × American Indian Mother | 1.48** | 0.148* | ||||||||

| (0.606) | (0.053) | |||||||||

| Interaction 2: Age Cohort 2 × American Indian Mother | 0.724 | 0.0141* | ||||||||

| (0.507) | (0.052) | |||||||||

| Interaction 3: Age Cohort 1 × American Indian Father | −0.915 | 0.114 | ||||||||

| (1.158) | (0.076) | |||||||||

| Interaction 4: Age Cohort 2 × American Indian Father | −0.886 | −0.180 | ||||||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.699) |

(0.161) |

| Number | 438 | 444 | 607 | 616 | 548 | 553 | 497 | 507 | 1044 | 1059 |

| Wald Chi-Squared (15) | 5.13 | 39.26 | 8.17 | 38.3 | 13.320 | 46.340 | 16.940 | 54.620 | 28.33 | 111.26 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1548 | 0.106 | 0.203 | 0.109 | 0.249 | 0.137 | 0.258 | 0.184 | 0.275 | 0.166 |

Note:

indicates coefficient statistically significant at the 1% level

at the 5% level

at the 10% level.

Includes: American Indian indicator, Gender, Mother's Highest Educational Attainment, Father's Highest Educational Attainment, Average Household Income prior to casino operation, age cohorts, and a constant.

Note: The Years of Education regressions are ordinary least squares, the probability of high school graduation regressions are probit regressions with marginal coefficients calculated.

Note: Robust standard errors are given in parenthesis below the estimated coefficients.

The next four columns of Table 4 divides the data according to the sex of the child in the survey and provides the same analysis for the educational outcome variables. In the first set of columns, the sample is restricted to male children and the next set of columns present only the female children's regressions. Examining the years of education regressions for each gender, it does not appear that years of education is differentially affected by restricting the sample by gender. Females appear to have a higher likelihood of finishing high school on time than boys.19 The results here are not as clear as the division by previous poverty status.

The final two columns of Table 4 disaggregates the data by the gender of the parent receiving the additional household income in order to investigate whether the additional household income has differential effects by the gender of recipient. In the two regressions, mothers who receive the additional household income have a positive and statistically significant effect on the total years of education and high school graduation rates for their children. Fathers, on the other hand, appear to have no noticeable impact when they receive additional household income. These results are qualitatively similar to Duflo (2003). In her paper, Duflo discusses the incentives for grandmothers to invest in their grandchildren as they have longer life expectancies than grandfathers and therefore reap the benefit of this grandchild health investment. It is not possible to conduct a similar analysis in our data without information on household expenditures. Nonetheless, it is still plausible that mothers spend more on their own children as they anticipate reaping the most benefit and assistance from their children later in life.

3.3 School Attendance in the Past Three Months

A secondary check on a child's educational achievement is a simple measure of school attendance. We investigate whether additional income affects school attendance rates throughout childhood. The dataset contains a variable which indicates the number of days present in school in the three months prior to the survey interview date; this particular question is asked at all of the childhood surveys. We remove all time-invariant household characteristics (both observed and unobserved) and control for the time-varying characteristics directly in our fixed-effects regression. Table 5 presents these fixed-effects results; in the first column we regress the number of days present in school in the last three months on the household's casino payment eligibility, household income, parental ages, child's age and the number of children less than six years old in the household. The results indicate that casino payment eligibility increases school attendance by almost two and half days per quarter. Dividing the data once again by households that previously were in poverty we find that the effect almost doubles in size: children from the poorest households with this additional income are present at school for almost four additional days than their untreated counterparts.20 The effect is still positive, however it is not statistically significant, for the households that previously were not in poverty. Overall, the additional household income appears to have a very strong effect on the child's school attendance at each survey wave.

Table 5.

Effect of Cash Transfer on Child's School Attendance in days for the previous quarter

| Number of Days Present Within the Last 3 Months |

Number of Days Present Within the Last 3 Months if Household Previously in Poverty |

Number of Days Present Within the Last 3 Months if Household Never in Poverty |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. |

| Household Eligible for Casino Disbursement | 2.43* | 3.85** | 2.420 |

| (1.280) | (1.943) | (1.720) | |

| Age of Child | 0.105 | −0.768 | 0.295 |

| (0.169) | (0.342) | (0.195) | |

| Number of Children | 0.447 | 1.156 | −0.591 |

| Less than 6 years old | |||

| |

(0.614) |

(0.794) |

(0.946) |

| Number of obs | 3317 | 1120 | 2197 |

| Number of groups | 1110 | 444 | 666 |

| Wald chi2(7) | 2.350 | 3.28 | 1.76 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.022 | 0.0021 | 0.092 |

Note: *** indicates coefficient statistically significant at the 1% level

at the 5% level

at the 10% level.

Note: All three regressions are ordinary least squares regressions with fixed-effects; standard errors clustered at the individual level and are given in parentheses below the estimated coefficients.

Note: Includes parents’ ages, income and income squared and a constant variable.

3.4 Criminal Behavior during Young Adulthood by Age and Offense Type

Table 6 examines the criminal behavior of all of the sample children. Administrative data has been merged with the GSMS data at the individual level with information on the number and nature of each crime for all of the survey children; in the final column of Table 6 we utilize self-reported data on drug dealing activities by the child. We classified the arrests into three broad categories of minor, moderate and violent offenses. Minor offenses includes disorderly conduct, trespassing and shoplifting; moderate offenses are property crimes such as felony larceny, drug-related crimes and simple assault. Major offenses include sexual assault, armed robbery and assault with a deadly weapon. Additionally, information about when the arrests occurred allows us to identify the ages (16−21) of arrests for each person.

Table 6.

Effect of Cash Transfer on Drug Dealing and Criminal Arrests by Age and Offense Type

| Any Crime by Age |

Ever Committed a Crime by Type |

Self-Reported Drug Dealing |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Committed Any Crime, Age 16−17 |

Committed Any Crime, Age 18−19 |

Committed Any Crime, Age 20−21 |

Ever Committed A Minor Crime by Age 21 |

Ever Committed A Moderate Crime by Age 21 |

Ever Committed A Violent Crime by Age 21 |

Ever Dealt Drugs by Age 21 |

|

| Independent Variables | Marg Coeff | Marg Coeff | Marg Coeff | Marg. Coeff | Marg. Coeff | Marg. Coeff | Coeff. |

| Interaction 1: Age Cohort 1 × Number of American Indian Parents | −0.224*** | −0.068 | 0.051 | −0.179** | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.065* |

| (0.078) | (0.072) | (0.075) | (0.089) | (0.065) | (0.012) | (0.033) | |

| Interaction 2: Age Cohort 2 × Number of American Indian Parents | −0.108* | −0.026 | 0.008 | −0.078 | −0.022 | −0.005 | −0.005 |

| (0.064) | (0.069) | (0.062) | (0.088) | (0.049) | (0.014) | (0.020) | |

| Age Cohort 1 (9 yo) | 0.076* | −0.011 | −0.068** | −0.051 | −0.017 | −0.003 | 0.000 |

| (0.043) | (0.052) | (0.033) | (0.055) | (0.026) | (0.009) | (0.016) | |

| Age Cohort 2 (11 yo) | −0.017 | −0.047 | −0.056 | −0.097* | −0.044* | 0.009 | 0.023 |

| (0.036) | (0.049) | (0.033) | (0.053) | (0.022) | (0.011) | (0.017) | |

| Number of American Indian Parents in Household | 0.136 | −0.043 | 0.091 | 0.096 | 0.114* | −0.011 | −0.019 |

| |

(0.091) |

(0.063) |

(0.078) |

(0.094) |

(0.068) |

(0.010) |

(0.019) |

| Number of obs | 1093 | 1061 | 1045 | 1045 | 1045 | 1045 | 1045 |

| F( 11, 1032) | 55.6 | 31.53 | 45.36 | 46.400 | 64.26 | 72.400 | 58.50 |

| Prob > F | 0 | 0.0028 | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| R-squared | 0.0837 | 0.0689 | 0.0806 | 0.082 | 0.096 | 0.185 | 0.122 |

Note: All regressions are probit regressions with marginal coefficients estimated; the robust standard errors are given in the parentheses below the estimated coefficients.

Includes: American Indian indicator, Gender, Mother's Highest Educational Attainment, Father's Highest Educational Attainment, Average Household Income, prior to casino operation and a constant.

Note:

indicates coefficient statistically significant at the 1% level

at the 5% level

at the 10% level.

The difference-in-difference regressions in the first three columns of Table 6 indicate that children from households that receive casino payments are 22% less likely to have been arrested at ages 16−17 than their untreated counterparts.21 Examining the effect on criminality in later years, ages 18−21, the additional household income has no direct effect on criminal arrests for either the first age cohort or the second age cohort. This result is somewhat puzzling but may be due to the fact that the children are no longer under their parents direct control after age 18. Therefore, the diversion in criminal behavior and arrests appears to be directly related to the child's minor status. The reduction in these criminal arrests are due to a reduction in male criminal activity; there is very little female criminal activity in general.

The next three columns in Table 6 presents the effect of additional household income on the child's criminal behavior by the type of crime committed. The first panel indicates that the reduction in criminal behavior occurs only in minor crimes. By age 21, a child who resided in a household with the additional casino income has an almost 18% lower probability of having ever committed a minor crime than a similar child from an untreated household. Further regressions that examined the effect of additional household income on the number of crimes (by category) did not yield significant results. This indicates that the additional income affected whether an individual entered into criminal behavior but not on the number of crimes once they had entered into criminality. Conducting a separate analysis for males alone, we find that the results hold up for minor crimes, if slightly diminished in significance, and become rather strong for moderate crimes.

A final measure of child criminal behavior is provided in the final column of Table 6. The child's self-reported drug dealing activities are regressed on the same set of explanatory variables used in the previous regression. The first interaction term indicates that children from households with exogenously increased incomes are almost 7% less likely to have reported dealing drugs at all in their youth. Restricting this to households that were previously in poverty, we do not find that there is any differential effects by previous poverty status; additional exogenous household income reduces the incidence of drug dealing for all types of households equally.

4 Potential Mechanisms

The previous section provided evidence that the exogenous increase in household income has positively affected young adult outcomes for children from these households. The results indicate that children from households with additional income have better educational attainment and reduced criminal behavior. In this section, we discuss a few of the potential mechanisms that may be contributing to the observed changes in child outcomes.

There are several potential explanations for why increased incomes may affect the young adult child outcomes. One potential explanation is that the additional household income is used to purchase better quality educational inputs. Unfortunately, the data does not contain consumption or expenditure data.22

4.1 Parental Labor Force Participation Rates

A second potential explanation is that parents use their additional income to substitute away from full time employment and into more childrearing. We have information on both parents’ labor force participation rates for each interview wave. Because we have panel data with regard to the parental labor force participation, we employ a quasi fixed-effect probit regression (Wooldridge, 2005) for the mother and father. In the first two columns of Table 7, we regress mother's labor force participation on whether the household was eligible for casino disbursements, a lag of household income, number of children less than six years old in the household and mother's age. The outcome variable is binary with one indicating either full time, part time or currently unemployed; a zero indicates the individual is out of the labor force - either retired, disabled or household worker for no pay. A positive coefficient on the casino eligibility variable indicates that the additional household income increases the labor force participation. The second regression uses a slightly more restrictive labor force participation binary variable: a value of one indicates full time participation only with zero being all other possibilities. Our results for both measures of labor force participation rates indicate that the additional household income does not affect the mother's labor force participation. A similar analysis is carried out for men in the next two columns. The point estimates are small in size and are also statistically insignificant. Therefore, it appears that households affected by cash transfers are not reducing their labor force participation.

Table 7.

Effect of Cash Transfer on Parental Labor Force Participation

| Mother's Labor Force Participation (FT, PT, UE) |

Mother's Labor Force Participation (FT) |

Father's Labor Force Participation (FT, PT, UE) |

Father's Labor Force Participation (FT) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Marg. Coeff | Marg. Coeff | Marg. Coeff | Marg. Coeff |

| Household Eligible for Casino Disbursement | 0.069 | −0.089 | −0.013 | 0.044 |

| (0.196) | (0.287) | (0.385) | (0.392) | |

| Lag of Household Income | 0.020 | −0.011 | 0.072 | −0.046 |

| (0.028) | (0.370) | (0.072) | (0.073) | |

| Number of Children | 0.031 | −0.03 | −0.236 | 0.054 |

| Less than 6 years old | ||||

| (0.096) | (0.125) | (0.285) | (0.296) | |

| Mother's Age | 0.011 | 0.021 | ||

| (0.017) | (0.023) | |||

| Father's Age | −0.102** | 0.122*** | ||

| |

|

|

(0.044) |

(0.047) |

| Number of obs | 3318 | 3318 | 1988 | 1988 |

| Number of groups | 1076 | 1076 | 643 | 643 |

| Wald chi2(7) | 343.31 | 243.96 | 104.54 | 110.52 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0 |

Note: Random effects probit regression specification for all four models as suggested by Wooldridge (2005). The regressions all include mother's initial labor force status, a lagged variable for mother's labor force status, a constant and the mean over all time periods for the following variables: household eligibility for casino, mother's age, the lag of household income, number of children below age 6. Robust Standard Errors are provided indicated below each estimated coefficient. A linear probability model with standard errors clustered at the individual level provides qualitatively similar results.

Note:

indicates coefficient statistically significant at the 1% level

at the 5% level

* at the 10% level.

4.2 Parental Behavior and Quality Measures

A third explanation is that parental quality improves with additional income. Increased household incomes may translate into lower levels of household stress and disruption. There is existing research that indicates that moving out of poverty may improve parental quality. McLeod et. al. (1993) find using the National Longitudinal Study of Youth (NLSY) data that currently poor mothers are more likely to spank their children and are less responsive to child needs. They also find that the persistence of poverty increases the direct internalization symptoms in children. Sampson et. al. (1994) find that poverty decreases adult stability and good decision-making. Ennis et al. (2000) have found that poverty can adversely affect mental health and depression among parents. Conger (1994) finds direct evidence that not having sufficient income produces stresses on individual parents.

We explore the possibility that the additional household income affects parental behavior and parent-child relationships. Additional information is available with regard to the two parents’ arrests since the last interview at each survey wave. In Table 8 we examine the effect of the per capita transfer on parental arrests. The first two columns presents a random effects probit regression on whether the mother or the father was arrested in the previous year at each survey wave.23 The results indicate that fathers have a reduced probability of being arrested when they come from households with the casino payments. We report marginal coefficients in this table, therefore, a father in a household which receives the casino transfers is about half as likely to have been arrested than another similar father from a household that does not receive the transfers. This effect is intensified for the households that were previously in poverty, however the sample size falls dramatically and is not shown here.

Table 8.

Effect of Cash Transfer on Parenting Measures and Parental Arrests

| Parental Arrests |

Parental Supervision |

Parental Activities with Child |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother Arrest Since Last Interview |

Father Arrest Since Last Interview |

Mother's Supervision |

Father's Supervision |

Parental Supervision |

Activities With Mother |

Activities With Father |

|

| Independent Variables | Marg. Coeff | Marg. Coeff | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. |

| Household Eligible for Casino Disbursement | −0.181 | −0.550** | 0.062*** | 0.096*** | 0.179** | 0.069*** | 0.035 |

| (0.210) | (0.260) | (0.023) | (0.032) | (0.067) | (0.024) | (0.036) | |

| Mother's Age | −0.036 | −0.001 | −0.003 | −0.003 | |||

| (0.022) | (0.004) | (0.010) | (0.004) | ||||

| Father's Age | −0.043 | 0.003 | 0.003 | −0.007 | |||

| (0.032) | (0.003) | (0.008) | 0.004 | ||||

| Age of Child | −0.014*** | −0.023*** | −0.045*** | −0.007 | −0.009 | ||

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.016) | (0.005) | (0.006) | |||

| Number of Children Less than 6 years old | 0.160 | −0.044** | −0.018 | −0.045 | −0.067 | −0.014 | 0.002 |

| |

(0.103) |

(0.020) |

(0.012) |

(0.030) |

(0.060) |

(0.018) |

(0.017) |

| Number of obs | 3473 | 2158 | 3802 | 2365 | 2025 | 3802 | 2367 |

| Number of groups | 1135 | 721 | 1163 | 745 | 637 | 1163 | 745 |

| Wald chi2(7) | 523.46 | 458.200 | 3.58 | 3.91 | 2.89 | 2.55 | 2.920 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.005 |

Note:

indicates coefficient statistically significant at the 1% level

at the 5% level

* at the 10% level.

Note: The parental arrests regressions are a random effects probit regression specification as suggested by Wooldridge (2005). The regressions include mother's initial labor force status, a lagged variable for mother's labor force status, a constant and the mean over all time periods for the following variables: household eligibility for casino, mother's age, the lag of household income, number of children below age 6. Robust Standard Errors are provided indicated below each estimated coefficient. A linear probability model with standard errors clustered at the individual level provides qualitatively similar results.

Note: The parental supervision and activities with parents regressions are linear probability fixed-effects regressions. The clustered standard errors are provided below the estimated coefficients. These regressions include controls for income, income squared, labor force status of the mother and father and a constant.

The results for parental arrests indicate that parents are engaging in less destructive behavior as a result of the increased incomes. This improvement in parental behavior and choices also tends to spill over into parent-child interactions and supervision. The GSMS data contains measures of parental supervision which asks the parent at each interview wave the percentage of time they know their child's whereabouts and activities. In the next three columns of Table 8 we conduct a fixed-effects regression of the mother and father's reported supervision of their child on the household's eligibility for casino payments, the child's age, household income, parental ages and the number of children below age six in the household. The positive coefficient on the casino disbursement indicates an improvement in mothers’ and fathers’ supervision separately as well as jointly in households receiving the additional income. These variables are given in categories and the mean is about 1.9 (where 2 represents age-appropriate knowledge of child's whereabouts) for both mothers and fathers; therefore, there is a 3% and 5% improvement in the parental supervision of their children over time. We find these to be moderate to large effects; they are larger in magnitude than even the coefficient on the child's age which should be an important determinant of parental supervision.

Finally, the last two columns of Table 8 present a direct measure of parental quality as reported by the child. Previous parental behavioral information was provided by the parent at all survey waves. The variable we consider here measures the amount of positive interactions between the child and parent from the child's perspective in the previous reference week. In both cases, the estimated coefficient is positive which indicates an improvement in parent – child interactions. The results indicate that there is a large improvement for the relationship between the child and the mother and that this improvement is statistically significant. The results are not statistically significant with regard to the father, while the estimated coefficient is of the same sign as the mother. Once again, we find these effects to be moderate to large relative to the other explanatory variables. The effect of the casino eligibility improves parent-child relationships by about 4% for mothers.

Overall, the results indicate that parents in households with additional incomes make better choices in their personal behavior and with regard to criminal behavior. They do not appear to make significant changes in their labor force participation efforts. Children report better relationships overtime in the households with additional income and parents report better supervision of their children over time in these same households. While there are many potential causal mechanisms at work here, it is useful to learn that parental time is not responsible for the observed changes in child outcomes. Parental quality and interactions with their children appears to be an important candidate for explaining how additional household income translates into better child outcomes.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Our results indicate that changes in a household's permanent income can have permanent effects. The effect on children continues on into young adulthood in our sample. We have seen that an exogenous treatment of increasing incomes tends to improve the overall child outcomes in terms of educational attainment at ages 19 and 21 and reduced criminal behavior at ages 16 and 17. Given the unique design of the research, we are able to control for several important confounding factors that might otherwise be the cause of the observed changes. We have been able to control for cohort differences by using a control group of non-treated households in our sample. Additionally, the comparison between the age 9 and age 13 cohorts provides us with the counterfactual observations of a household where incomes were unchanged for a shorter period of time (6 years versus 2 years). We find that in general there is an overall improvement in the outcomes of the American Indian children while those of the non-Indian children have remained mostly stable. We see for the educational outcomes that American Indians have made big strides and have converged to that of the non-Indians. On the other hand, with regard to the criminal arrests, American Indians have diverged and now are less likely than the non-Indians (whose rates of arrests remained constant over time) to commit these minor crimes.24

We have also explored a couple of the potential mechanisms that transform additional household income into better child outcomes. While it is not possible in this analysis to definitively identify the true causal mechanism responsible for the improvement in young adult outcomes, we have been able to identify a few changes in parental behavior (parental quality) that is suggestive of a mechanism. Parents have a better overall relationship with their children after the additional household income is introduced as evidenced by responses from both the parent and child. Additionally, parents appear to have less problems over time once the exogenous income is introduced: we see that fathers are less likely to be arrested themselves over time. On the other hand, we do not have much evidence that the additional income is used by parents to make a dramatic shift from labor force participation towards more child care (parental quantity). While our data is not perfect, it appears that neither mothers nor fathers are leaving the labor force because of the additional household income. More research that focuses on the mechanisms that translate household incomes into child well-being is certainly needed.

It is important to note the differences from this research and previous efforts. The program described here differs in at least two dimensions: size and duration. The size of the casino payments is large relative to other income augmentation programs and certainly with regard to other quasi-experimental policies. The additional $4000 dollars per year represents anywhere from 1/4 to 1/3 of many of these household's incomes. Second, this casino disbursement program has no foreseeable end date. While it is contingent upon successful and continued operations of the casino, there has been no indication that there would be a change in the program or that profits have decreased over time. Therefore, people treat these changes in their income as permanent and spend accordingly. These two effects are probably responsible for the large effects found in this research which are not often evident in studies with smaller amounts and temporary income changes.

Future work will allow us to explore the effect of this additional income on the geographic mobility of the children. The casino payments are not limited by geographic proximity to the Eastern Cherokee reservation. Therefore, in future work we anticipate evaluating how this additional income has increased the geographic distribution of these children from American Indian households- individuals may move out of state and they will still be eligible for casino payments. In future survey waves we shall also have additional employment information for the children at ages 24 and 25 which will allow us to explore whether they differentially enter into different occupations and industries and any resulting wage differentials.