Abstract

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) upregulation is an early event in the development of non-small cell lung cancer. Preclinical data indicate tumors with upregulation of COX-2 synthesize high levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) which in turn are associated with increased production of proangiogenic factors and enhanced metastatic potential. These findings suggest that an increase in COX-2 expression may play a significant role in the development and growth of lung cancers and possibly with the acquisition of an invasive and metastatic phenotype. Consequently, inhibitors of COX-2 are being studied for their chemopreventative and therapeutic effects in individuals at high risk for lung cancer and patients with established cancers.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in North America with an estimated 213,380 new diagnoses of lung cancer anticipated in 2008 and approximately 160,390 of these patients are expected to die from this disease.1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80–85% of lung cancer cases. The prognosis for this disease is poor. Even when detected early, up to 50% of patients with pathologic stage I disease eventually relapse post-resection and eventually die of their disease. For the two-thirds of patients presenting with locally advanced or metastatic disease, the median survival is typically less than one year.2 Therefore, novel strategies that offer significant improvements to prolong patients’ survival are needed for this all too common malignancy.

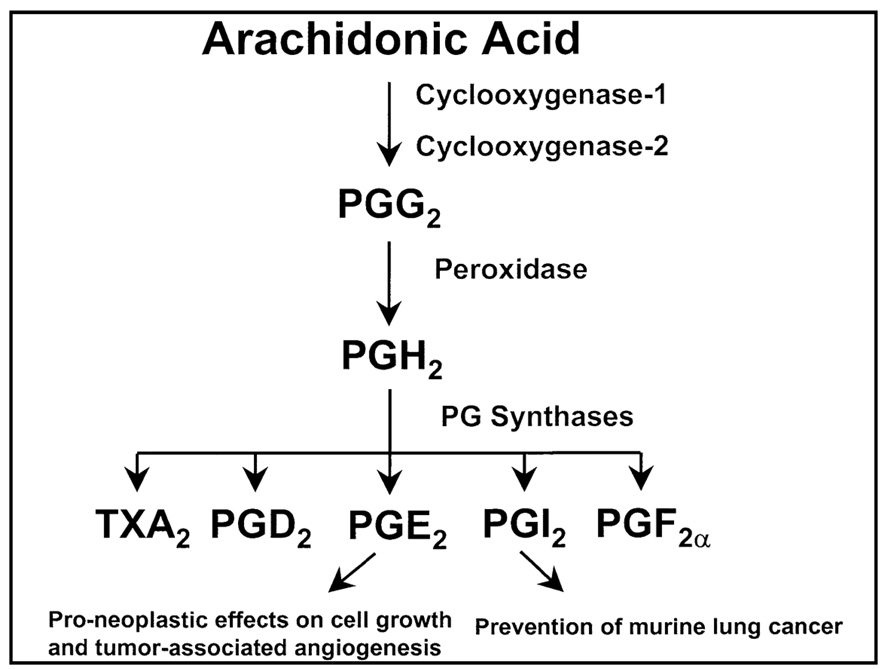

As our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of lung cancer biology has improved over the last two decades several new potential therapeutic targets have been recognized.3 Preclinical and clinical data indicate that changes in the eicosanoid pathway may provide opportunities to develop novel therapies for the treatment of patients with NSCLC.4,5 The generation of eicosanoids, which includes prostaglandins (PG), thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and prostacyclins are signaling molecules produced from the oxidation of arachidonic acid (Figure 1).4–6 Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), one of two isoforms of COX which catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid to PGs, is frequently upregulated in NSCLC,7–10 and can result in elevated levels of COX-2 derived prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). Increases in this bioactive lipid have been shown to contribute to the malignant phenotype by promoting tumor angiogenesis, increasing cellular migration and invasive potential, producing alterations in cell cycle progression, reducing apoptosis and inhibiting immune surveillance.6

Figure 1.

Arachidonic acid metabolism leading to the generation of eicosanoids.

Overview of COX-2 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Cyclooxygenase-2 is an immediate early response gene; its expression is normally absent in most cells and tissues but it is highly induced in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines, hormones and tumor promoters.6 COX-2 expression has been documented in up to one-third of lung atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and carcinoma-in-situ and is over-expressed in 70% to 90% of NSCLCs, especially in adenocarcinomas. 7–10 One group reported a greater proportion of lung cancer cells staining positively for COX-2 in lymph node metastases compared to the corresponding primary tumor.8 Others have shown a correlation between COX-2 expression and phenotype. COX-2 protein levels are elevated in stage I disease and confer a poor prognosis; and increased COX-2 mRNA levels portend a worse overall survival rate and aggressive disease in NSCLC.11–13 These reports imply a potential role for COX-2 in the pathogenesis of lung cancer and that COX-2 is an independent poor prognostic indicator.

The precise mechanisms responsible for elevated COX-2 expression in lung cancer are not completely understood; however, COX may directly impact on lung carcinogenesis because it can activate environmental carcinogens.14 Conversely benzo(a)pyrene itself along with other components of tobacco smoke can induce COX-2 expression and PGE2 production.15,16 Many other stimuli present in the pulmonary microenvironment that are associated with increased risk of lung cancer development can also induce COX-2 expression.4 Although the specific clinical relevance of these observations is unclear; the selective COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, has been shown to retard growth of lung tumors implanted into recipient mice in a dose dependent manner and to enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy agents.17 Investigators have also demonstrated a tumor growth inhibitory effect on NSCLC using either a selective or non-selective inhibitor of COX-2, both alone and in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy.18–22 Recently, a phase III study of 204 patients with at least a 20 pack-year smoking history randomized patients to one of four treatment arms: celecoxib followed by a placebo, placebo followed by celecoxib, celecoxib followed by continued celecoxib or placebo followed by continued placebo - each of 3 months duration.23 Celecoxib was administered at “low dose” (200 mg BID) to 81 patients then changed to “high-dose” (400 mg BID) for an additional 123 patients. Basal and pre-basal Ki-67 expression in bronchial biopsies was measured as a surrogate for cellular proliferation, at baseline, 3 and 6 months. Bronchial pre-malignant lesions were shown to have increased Ki-67. Notably baseline Ki-67 was elevated in basal and pre-basal layers in current smokers compared to former smokers. Patients treated with high dose celecoxib had a significant decrease in Ki-67 (P=0.003), a change not observed with low dose celecoxib. No cardiac toxicities were observed; however, celecoxib was administered for only a brief period of time. These data suggest that celecoxib, in relatively high doses, can decrease cellular proliferation and may prevent the development of invasive tumors in patients at high risk for lung cancer. This is analogous to what has been observed in patients with colon polyps who are at high risk for development of colon cancers.24,25

First Line Chemotherapy plus COX-2 Inhibitors

The Gemcitabine-Coxib (GECO) study evaluated the addition of the specific COX-2 inhibitor rofecoxib to first line chemotherapy in patients with stages IIIB or IV NSCLC.26 In this prospective phase III trial, an open-label 2x2 factorial design, two different chemotherapy regimens gemcitabine (1200 mg/m2 days 1 and 8) and cisplatin (80 mg/m2 day 1 every 21 days) versus prolonged constant infusion (PCI) gemcitabine (1200 mg/m2 days 1 and 8) and cisplatin (80 mg/m2 day 1) were administered with and without rofecoxib (50 mg OD). Rofecoxib was continued until disease progression. The study was interrupted with the recognition that long term high dose therapy was associated with increased cardiovascular toxicities prompting the manufacturer’s withdrawal of rofecoxib from the market.27 At that time 299 of the planned 400 patients had been randomized. However, the final sample for analysis of the effect of rofecoxib was lower than anticipated. To compensate, the study investigators allowed longer follow up so power only slightly decreased. Treatment continued as planned for the two gemcitabine groups. The major grade 3 and 4 toxicities in the chemotherapy treatment arms included neutropenia and febrile neutropenia, fatigue and emesis were more severe in patients treated with PCI gemcitabine. Patients treated with rofecoxib had a significantly higher incidence of diarrhea and severe heart ischemia, but less fatigue, fever and weight loss compared to those who did not receive rofecoxib. Patients receiving rofecoxib also reported less pain and analgesic use as well as significantly improved quality of life, physical, emotional and role functioning, and improved sleep. The addition of rofecoxib to chemotherapy resulted in a significant increase in overall response (41% vs. 26%; P=0.02); however, there was no difference in median progression free survival (PFS) (5.8 vs. 5.3 months; P=1.00) or overall survival (OS) (10.2 vs. 10.2 months; P=1.00) (Table 1). Unfortunately due to lack of sufficient tissue samples to measure COX-2 expression no correlative studies were undertaken.26

Table 1.

1st Line Treatment plus COX-2 Inhibitor in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer:

| Author: | CT: | Inhibitor: | Pt No: | ORR: | MST: | 1-Yr: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gridelli26 | Cisplatin 80 mg/m2+ Gemcitabine (1200 mg/m2) |

Rofecoxib 50 mg OD |

251 | 41% | 10.2 mo | 42% |

| Cisplatin 80 mg/m2+ Gemcitabine (1200 mg/m2) |

149 | 26% | 10.2 mo | 40% | ||

| Edleman28 | Carboplatin (AUC 5.5) + Gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) |

Zileuton 600 mg QID |

44 | 25% | 9.4 mo | 42% |

| Carboplatin (AUC 5.5) + Gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) |

Celecoxib 400 mg BID |

45 | 24% | 11.8 mo | 45% | |

| Carboplatin (AUC 5.5) + Gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) |

Zileuton 600 mg QID + celecoxib 400 mg BID |

45 | 36% | 9.4 mo | 40% | |

| Gadgell35 | Docetaxel (36 mg/m2) | Celecoxib 400 mg BID |

34* | 15% | 5.0 mo | NR |

| Burton39 | Carboplatin (AUC 5) + Gemcitabine (1100 mg/m2) |

Celecoxib 120–600 mg/m2 |

32 | 24% | NR | NR |

patients ≥70 years or PS = 2

Dual eicosanoid inhibition with celecoxib and zileuton was evaluated by Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) investigators in a randomized phase II trial of 134 chemotherapy naïve, patients with advanced NSCLC (CALGB 30203).28 Zileuton inhibits 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO), a key enzyme in the formation of leukotrienes.29 Leukotrienes are involved in the normal physiologic response of the body and act to regulate inflammatory and allergic reactions. Zileuton has been shown to inhibit lung tumorigenesis in vitro30 and in vivo31 in carcinogen-treated mice. In the CALGB 30203 trial, patients received carboplatin (AUC 5.5 day 1) and gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2 days 1 and 8 every 21 days) and were randomly assigned to zileuton alone (600 mg QID), celecoxib alone (400 mg BID) or the combination of zileuton and celecoxib. Except for a slightly higher rate of grade 3 nausea and vomiting in patients treated with celecoxib, treatment toxicities were similar in all three treatment groups and equivalent to that seen with chemotherapy alone. There was a higher response rate for patients receiving celecoxib alone compared to those receiving zileuton alone or the combination of celecoxib and zileuton (RR = 36% vs. 25% vs. 24% respectively). The failure free, overall and 1-year survival results (4.9 months, 10.3 months and 42%) (Table 1) were similar to what was seen in the aforementioned GECO trial26 and not different to what is commonly achieved with chemotherapy alone.2,32,33 Immunohistochemistry for expression of 5-LO and COX-2 was performed on 83 tumor specimens. As previously reported, 12,34 moderate to high expression of intratumoral COX-2, as defined by these investigators, was found to be a negative prognostic factor. Patients with tumors that over-expressed COX-2 had a significantly worse median survival compared to those with low COX-2 expression (3.8 vs. 12.0 months, P = 0.02) (Table 2a). The addition of celecoxib to chemotherapy improved overall survival only for patients with moderate to high COX-2 expression (COX-2 ≥ 4 HR 0.34; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.75; COX-2 >9 HR 0.18, CI 0.07,to 0.58) suggesting COX-2 expression is also potentially a predictive factor (Table 2b).28 These data suggest high COX-2 expression may identify a subset of lung cancer patients that would benefit from the addition of celecoxib to standard chemotherapy.

Table 2.

| Table 2a: COX-2 Expression as a Prognostic Marker in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival: | ||||

| COX-2 Index: | HR: | P Value: | Low Expression: |

High Expression: |

| ≥1 | 1.65 | 0.208 | 13.3 mo | 7.1 mo |

| (0.752, 3.611) | (7.3, 18.4 mo) | (3.4, 15.7 mo) | ||

| ≥4 | 2.51 | 0.019 | 13.3 mo | 3.8 mo |

| (1.138, 5.555) | (9.4, 18.4 mo) | (0.9, 10.5 mo) | ||

| 9 | 4.16 | 0.005 | 12.0 mo | 4.0 mo |

| (1.437, 12.010) | (7.3, 16.7 mo) | (3.4, 6.5 mo) | ||

| Table 2b: COX-2 Expression as a Predictive Marker in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival: | ||||

| COX-2 Index: | HR: | P Value: | No Celecoxib: | Rec’d Celecoxib: |

| <1 | 1.43 | 0.384 | 13.3 mo | 8.6 mo |

| (0.638, 3.201) | (7.3, 18.4 mo) | (4.9, 14.9 mo) | ||

| ≥4 | 0.34 | 0.005 | 3.8 mo | 11.3 mo |

| (0.155, 0.752) | (0.9, 10.5 mo) | (9.2, 17.6 mo) | ||

| 9 | 0.18 | 0.002 | 4.0 mo | 12.1 mo |

| (0.066, 0.576) | (3.4, 6.5 mo) | (8.0, 16.0 mo) | ||

Slides were scored for intensity of staining (0 to 3) and the percentage of cells scored 0 (0%), 1 (1% to 9%), 2 (10% to 49%), 3 (50% to 100%). The immunohistochemistry (IHC) index (0–9) was defined as the product of the intensity and percentage of cells.28

Other investigators have also attempted to incorporate COX-2 inhibitors into front-line therapy for advanced NSCLC. For example, Gadgeel and colleagues evaluated docetaxel (36 mg/m2 days 1, 8, 15 every 28 days) and celecoxib (400 mg BID) in a phase II study of chemotherapy naïve elderly (≥ 70 years of age) or ECOG performance status 2 patients with advanced NSCLC.35 Celecoxib was initiated seven days prior to chemotherapy. This trial was closed early due to emerging reports of excessive cardiac toxicities occurring with selective COX-2 inhibitors.36 At the time of study closure 34 patients had been enrolled, 79% of patients were ≥ 70 years of age and 56% had a PS=2. Only three patients continued on single agent celecoxib after chemotherapy. There were no treatment related deaths; however, there were two episodes of grade 4 arterial thrombotic events (one patient with a myocardial infarction and another with a cerebrovascular accident), and two patients developed grade 4 venous thrombosis (DVT = 1; PE = 1). One patient with a prior history of intestinal surgery and adhesions had a fatal intestinal obstruction. Grade 3/4 fatigue was seen in 20% of patients. Thirty patients were evaluable for response. The overall response rate was 15%. Progression free and overall survival were 2.3 and 5 months respectively, not superior to prior studies with single agent docetaxel.37,38

Burton and colleagues conducted a phase I/II trial combining carboplatin (AUC 5 day 8) plus gemcitabine (1100 mg/m2 days 1,8 every 21 days) with an escalating dose of celecoxib starting at 120 mg/m2 and increasing to a maximum dose of 600 mg/m2 (or ≍500 mg BID) days 1–12.39 Response was assessed every 2 cycles and those patients with stable disease or better were to receive up to 8 cycles of therapy. Celecoxib was tolerated at the final dose level (600 mg/m2). There were seven episodes of grade 4 hematologic toxicity and five episodes of grade 3 hepatic toxicity. Overall response was 24% (1 CR, 5 PR) and 14 patients had stable disease. No further follow-up information is available. At last report the study continued to accrue patients at the 600 mg/m2 dose level.

Neo-Adjuvant Chemotherapy plus COX-2 Inhibitors

The role of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of NSCLC is controversial; however, this setting is potentially useful to assess the efficacy of molecularly targeted therapies.40 Altorki and colleagues administered preoperative celecoxib (400 mg BID) plus paclitaxel (225 mg/m2 day 1) and carboplatin (AUC 6 day 1) to patients with stages IB-IIIA NSCLC.41 Nineteen of the 29 patients (65%) enrolled achieved a complete or partial clinical response. Three patients discontinued celecoxib after developing a generalized skin rash (2 PR, 1 PD). There were no complete pathological responses; however, seven patients had only minimal residual microscopic disease which has been shown to predict long term survival.42 Major grade 3/4 toxicities included neutropenia and neuropathy, similar to treatment with carboplatin plus paclitaxel alone.2 There were two deaths reported; one from neutropenic sepsis following chemotherapy and one due to respiratory failure one week following a right-sided pneumonectomy. Pre-operative treatment with celecoxib did not appear to affect wound healing, a concern given this agent’s putative antiangiogenic effects.17 Taxanes have been shown to increase the levels of COX-2 expression and PGE2 synthesis in the preclinical setting,43 potentially compromising the antitumor activity of these agents. Thus, PGE2 levels were measured in both tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues in 17 patients enrolled in this study as well as 13 patients who had received the same chemotherapy off study and 16 patients who underwent surgical resection alone. Intratumoral PGE2 levels were more than twice as high among patients who received preoperative chemotherapy as compared with tumors treated by surgical resection alone (384 vs. 150 pg/µg protein; P<0.001), consistent with the preclinical observations.43,44 Increased levels of intratumoral PGE2 were associated with a significant increase in amounts of intratumoral COX-2. By contrast, the addition of celecoxib to preoperative chemotherapy led to a “normalization” of levels of intratumoral PGE2 but no change in intratumoral COX-2 expression indicating celecoxib inhibited COX-2 enzyme activity and not protein expression.44

Based on the above results a second phase II trial was opened in Italy In which chemotherapy naïve stage IIIA/B NSCLC patients were treated with cisplatin (80 mg/m2 day 1) plus fixed-dose-rate gemcitabine (1200 mg/m2 days 1 and 8) and celecoxib 400 mg BID.45 After three cycles of neoadjuvant therapy patients were restaged and those who had not progressed proceeded to surgery and/or definitive radiation therapy. Of the 19 evaluable patients, three achieved a clinical complete and seven had partial responses (53%); seven patients had stable disease (37%). There were two pathologic complete responses in the nine patients that underwent surgical resection, possibly attributable to the use of cisplatin rather than carboplatin as employed by Altorki and colleagues 41 [see above]. At a median follow up of 42 weeks, nine patients were still alive and without progression. Accrual to this study is reportedly ongoing.

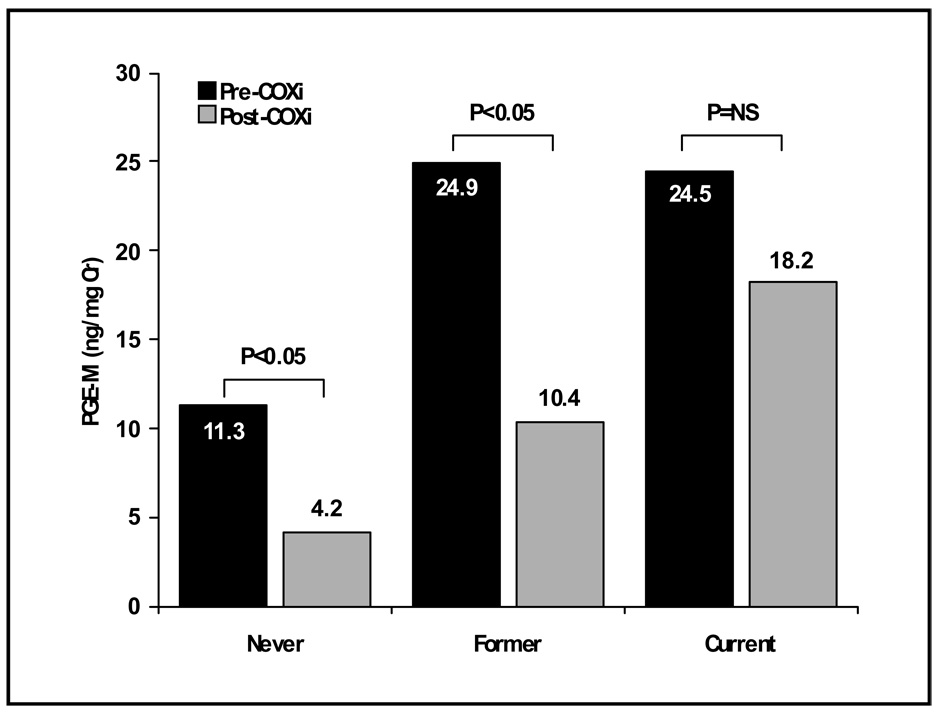

Second Line Chemotherapy plus COX-2 Inhibitors

Docetaxel is an FDA approved second line agent for the treatment of NSCLC patients based on studies showing improved survival and quality of life.38,46 In preclinical studies, docetaxel combined with a selective COX-2 inhibitor results in greater cytotoxicity compared with docetaxel or a COX-2 inhibitor alone.20 Based in part on these data, Csiki and colleagues undertook a phase II trial in which docetaxel (75 mg/m2 day 1) was combined with celecoxib 400 mg BID.47 Celecoxib was initiated one week prior to chemotherapy to assess its specific effect on PGE2 production and was then continued until disease progression. The study enrolled 56 NSCLC patients who had failed up to two prior chemotherapy regimens. Grade 3/4 toxicities included neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, infection, nausea, emesis, dehydration and diarrhea. The overall response rate was 11% with a median and 1 year survival rate of 6 months and 23% respectively (Table 3), results that are similar to prior studies with docetaxel alone. 37,38,46 As a measure of target acquisition, these investigators assessed inhibition of intratumoral PGE2 production as well as the levels of the major urinary metabolite of PGE2 (11α-hydroxy-9,15-dioxo-2,3,4,5-tetranor-prostane-1,20-dioic acid or PGE-M) before and after a brief course of single agent celecoxib. Measurement of urinary PGE-M is considered the most accurate way of assessing systemic production of PGE2.48,49 The majority of urinary PGE-M in NSCLC patients is thought to emanate from PGE2 derived from intratumoral COX-2 since COX-2 is not constitutively expressed in normal tissues.50 Intratumoral PGE2 levels fell in all six patients in whom it was measured and was associated with a concomitant fall in urine PGE-M levels. Among all patients enrolled there was a significant drop in mean urinary PGE-M following a 5–7 day course of celecoxib. Notably baseline urinary PGE-M levels were higher in former and current smokers compared to never smokers and the observed decrease in PGE-M was more pronounced in never and former as compared to current smokers (Figure 2). These results are consistent with recent studies that demonstrate exposure to tobacco smoke stimulates PGE2 synthesis through upregulation of COX-2.51 In an exploratory analysis, patients with ≥72% decrease in urinary PGE-M were found to have a better survival (median = 15 months; 1-year = 36%) compared to patients with a lesser decline (median = 6.3 months; 1-year = 24%) or an increase in PGE-M (median = 5.0 months; 1-year = 0%). These data, along with those from the CALGB 30203 trial,28 suggest there may be a subset of NSCLC patients that derive significant benefit from the combination of COX-2 inhibition and chemotherapy (i.e. “COX-dependent” NSCLC). Celecoxib also resulted in expected alterations in the concentrations of pro- and anti-angiogenic factors, namely decreases in serum VEGF and increases in endostatin levels. However, alterations in these biomarkers did not correlate with clinical outcome and were therefore not thought to be useful surrogate markers for COX-2 inhibition.47

Table 3.

2nd Line Treatment plus COX-2 Inhibitors in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer:

| Author: | Treatment: | Celecoxib: | No: | ORR: | MST: | 1- Yr: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Csiki47 | Docetaxel (75 mg/m2) |

400 mg BID |

56 | 11.0% | 6.0 mo |

23% |

| Nugent52 | Docetaxel (75 mg/m2) |

400 mg BID |

41 | 10.2% | 11.3 mo |

48% |

| Schneider53 | Docetaxel (75 mg/m2) |

400 mg BID |

20 | 15% | 5.0 mo |

NR |

| Gasparini55 | Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2/wk × 6) |

400 mg BID |

58 | 24.1% | 11.0 mo |

43% |

| Irinotecan (60 mg/m2) + Docetaxel (35 mg/m2) or |

400 mg BID |

67 | 3.0% | 6.31 mo |

24% | |

| Lilenbaum58 | ||||||

| Irinotecan (60 mg/m2) + Gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) |

None | 66 | 6.1% | 8.99 mo |

36% | |

Figure 2.

Pre- and post-celecoxib PGE-M levels in never, former, and current smokers. PGE-M levels were quantified by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization MS using selected reaction monitoring. Precision of the assay is ±5% and accuracy is 92%. Columns, means.47

Nugent and colleagues also administered docetaxel (75 mg/m2 day 1) plus celecoxib to 41 NSCLC patients who had failed one prior platinum-based chemotherapy.52 The majority of patients had received a taxane as part of their initial therapy. These investigators reported an overall response of 10.2%. Progression-free and overall survival were 4.6 months (95% CI: 3.2, 5.8) and 11.3 months (95% CI: 7.9, 15.7) respectively. Patients who did not have prior taxane chemotherapy had a significantly longer time to disease progression compared with those who had received therapy with paclitaxel (1.7 vs. 7.4 months; log-rank P = 0.026) although there was no overall survival difference (P = 0.66) (Table 3). There was a correlation between tumor histology and survival with patients with adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas surviving longer than those with undifferentiated and large cell histology. Major grade 3/4 toxicities included neutropenia and febrile neutropenia. No biological correlates accompanied this study.

A third phase II study employing celecoxib (400 mg BID) with docetaxel (75 mg/m2 day 1) was performed in patients with relapsed NSCLC by Schneider and his associates.53 All eligible patients had failed previous platinum-based chemotherapy. Twenty-four patients were enrolled, 20 were eligible for evaluation and two (10%) experienced a partial response while 12 patients had stable disease. Four patients never received docetaxel. One patient developed pneumonia, one took celecoxib for just two days and then rescinded consent and two patients experienced a severe decline in performance status necessitating removal from the trial prior to receiving docetaxel. The median number of cycles of chemotherapy delivered was two (range, 1–14). Median time to treatment failure was 1.7 months (95% CI: 1.3–2.9) whereas median and 1-year survival were 6.9 months (95% CI: 2.8–15.2) and 36% (95% CI: 15–57%) respectively (Table 3). Major grade 3/4 toxicities included neutropenia and neutropenic fever (21%), a side effect profile consistent with that observed by Csiki and colleagues and Nugent and colleagues as well.47,52 The authors pointed out that COX-2 activity may be required for normal marrow recovery after cytotoxic therapy.54 The combining of a COX-2 inhibitor with chemotherapy may therefore lead to greater hematologic toxicity. Of note, no patient required a dose reduction of celecoxib due to non-hematologic toxicities.

Gaspirini and colleagues administered celecoxib 400 mg BID with weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2/week x 6 weeks every 8 weeks) to NSCLC patients who had failed first line platinum-based chemotherapy.55 Grade 3 and 4 toxicities included leucopenia, neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy. Fifty-five of the 58 patients enrolled were assessable for response one of whom achieved a complete response while 13 were noted to have a partial response for an overall response rate of 24% (95% CI: 13.9–37.2%). An additional 24 patients (41%) had stable disease. The median progression-free, overall and 1 year survival of 5 months, 11 months, and 42.5% respectively (Table 3) were seemingly superior to that observed in an earlier phase II study of weekly paclitaxel alone.56 As possible biomarkers of celecoxib’s activity these investigators assessed serum VEGF and IL-6 at baseline and every two treatment courses thereafter. Therapy did not influence concentrations of IL-6. By contrast, patients achieving a partial response had a statistically significant decrease in serum VEGF (P=0.0176). However, because weekly paclitaxel itself may be anti-angiogenic, it is not possible to attribute the apparent antiangiogenic effect solely to celecoxib.57

Finally, the largest phase II trial to assess the effect of COX-2 inhibition in the setting of recurrent NSCLC was conducted by Lilenbaum and colleagues.58 These investigators randomized 133 patients to doublet chemotherapy with irinotecan (60 mg/m2 days 1 and 8) plus docetaxel (35 mg/m2 days 1 and 8) or irinotecan (100 mg/m2 days 1 and 8) plus gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2 days 1 and 8) with or without celecoxib (400 mg BID). All patients had failed at least one prior platinum-based therapy. Grade 3 and 4 toxicities included neutropenia among all patients, anemia for patients receiving irinotecan plus gemcitabine with celecoxib and thrombocytopenia for patients receiving irinotecan plus gemcitabine with or without celecoxib. Patients treated with celecoxib experienced improvement in pain in a quality of life assessment. However, the overall response rate (3.0% vs. 6.1%), progression-free (1.81 vs. 2.1 months), median (6.3 vs. 9.0 months) and 1-year survival (24% vs. 36%) were all inferior for patients treated with celecoxib and chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone (Table 3).

No correlative biological studies accompanied the Lilenbaum study which is unfortunate as they may have proved useful in understanding these negative results. For example, in some preclinical settings, celecoxib has been found to induce nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) activation with resultant increased expression of NFκB-dependent genes such as bcl-2, bcl-XL and survivin that in turn lead to decreased apoptosis.59 At clinically relevant concentrations, celecoxib also can induce multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP-4) expression.60 As irinotecan is a substrate transported by MRP-4 61 celecoxib could theoretically enhance the extrusion of irinotecan from tumor cells thereby reducing the irinotecan efficacy and worsening the outcome of patients treated with both agents.60 Moreover, a recent phase I trial combining celecoxib with docetaxel and irinotecan found that although the pharmacokinetics of docetaxel were not affected by celecoxib there was an 18% increase in the elimination clearance of irinotecan.62 Any of these effects could reduce the efficacy of irinotecan when administered in combination with celecoxib potentially accounting for the negative results obtained in the Lilenbaum trial.

EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors plus COX-2 Inhibitors

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a key step during embryonic morphogenesis. Over the last few years, increasing evidence has shown that EMT plays an essential role in tumor progression and cancer metastasis.63,64 Several distinct traits have been conveyed by EMT, including cell motility, invasiveness, resistance to apoptosis, and some properties of stem cells. Many signal pathways contribute to the induction of EMT, such as transforming growth factor-β, Wnt, Hedgehog, Notch, and NFκB. Understanding the molecular mechanism of EMT may lead to novel interventions for metastatic disease. For example, loss of E-cadherin is a hallmark of EMT and is associated with tumor progression and metastasis.63,65 High E-cadherin expression or a gene signature associated with a mesenchymal rather than epithelial phenotype appears to be linked to sensitivity to EGFR TKI in NSCLC.66,67 Dubinett and colleagues have shown that PGE2 and other inflammatory mediators derived from neoplastic, stromal and immune cells reduce tumor E-cadherin levels in NSCLC via MAPK/Erk-dependent up-regulation of the transcriptional repressors zinc-finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB-1) and zinc-finger factor Snail homologue 1 (Snail).68–70 By suppressing E-cadherin, PGE2 and possibly other inflammatory cytokines in the tumor microenvironment may play a role in EGFR TKI resistance in NSCLC.65 COX-2 inhibitors can potentially reverse this effect.70 Accordingly combining inhibitors of COX-2 with EGFR TKIs may have a beneficial effect, a hypothesis undergoing active investigation. For example, Reckamp and colleagues combined erlotinib (150 mg QD) with escalating doses of celecoxib (200 to 800 mg BID) in a phase I dose escalation study designed to determine the optimal biological dose of this combination.71 Rash, diarrhea and anemia were the most common toxicities reported. Of the 22 patients enrolled, all of whom had previously treated recurrent NSCLC, seven (33%) achieved a partial response and five patients (23%) experienced stable disease (Table 4). Younger age and positive EGFR mutation status were statistically correlated with response (P=0.0247 and P=0.0034 respectively). The duration of response ranged from 5.6 to 22.1 months. Urinary PGE-M levels were measured at baseline and again after 4 and 8 weeks of treatment. PGE-M levels were significantly lower at weeks 4 and 8 compared to baseline levels (P=0.0034 and P=0.0537, respectively); however, there was no significant difference in PGE-M levels at 4 and 8 weeks. Changes in urinary PGE-M at 4 weeks correlated with celecoxib dose (P<0.00001). At the celecoxib 200 or 300 mg doses there was <10% decline in PGE-M levels but with the higher celecoxib doses of 400 mg, 600 mg and 800 mg there was a 65%, 87% and 84% decline respectively. In this patient population celecoxib 600 mg twice daily was determined to be the optimal biological dose when combined with erlotinib.71 FDG-PET was also examined as a potential marker of early tumor response. One patient with a partial response by RECIST at 8 weeks had a 45% decrease in SUV on FDG-PET at one week. Based on these results a randomized phase II trial of erlotinib with or without celecoxib is underway in patients with recurrent NSCLC. FDG-PET response will be used as a early marker of efficacy.

Table 4.

COX-2 Inhibitor plus EGFR Inhibitors in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer:

| Author: | EGFR Inhibitor: | COX-2 Inhibitor: |

Pt No: | ORR: | MST: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reckamp71 | Erlotinib 150 mg OD | Celecoxib 200–800 mg BID |

21 | 33% | NR |

| Fidler72 | Erlotinib 150 mg OD | Celecoxib 400 mg BID |

26 | 8% | 9.2 mo |

| Gadgeel75 | Gefitinib 250 mg OD |

Celecoxib 400 mg BID |

27 | 7% | 4.6 mo |

| Agarwala77 | Gefitinib 250 mg OD* |

Celecoxib 400 mg BID |

31 | 16% | 7.2 mo |

| O’Bryne78 | Gefitinib 250 mg OD |

Rofecoxib 50 mg QD |

42 | 5% | 4.7 mo |

1st line therapy

Fidler and colleagues also conducted a phase II trial evaluating erlotinib (150 mg QD) with a fixed dose of celecoxib (400 mg BID) in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC.72 However, this trial was stopped prior to its planned accrual goal after four of the initial 26 patients experienced a major upper GI hemorrhage. Two of the patients with GI bleeding were on anticoagulation therapy with warfarin and therefore at risk for a known potential adverse drug interaction,73 a third patient was on low molecular weight heparin while the fourth patient had a remote history of peptic ulcer disease. Bleeding peptic ulcers were documented in three patients who consented to diagnostic endoscopy. A fifth patient on therapeutic anticoagulation did not bleed. Additional toxicities included grade 1/2 rash or diarrhea in 85% and 65% of patients respectively. Rash and fatigue led one patient to discontinue treatment. Two (8%) patients achieved a partial response and eight (30%) patients had stable disease. Median progression free survival (PFS) was 2.8 months while median and 1-year survival were 9.2 months and 31% (Table 4), similar to that observed with erlotinib alone in this patient population.74 Twenty-one patients had tissue available for COX-2 immunohistochemistry analysis. Using the definition developed by the CALGB group,28 high COX-2 expression was noted in 11 of 21 patient (52%). Notably, a high COX-2 expression was associated with a significant improvement in PFS (5.5 vs. 2.0 months; log rank P<0.048) (Figure 2). Patients with tumors that demonstrated COX-2 staining in >50% of cells had a prolonged PFS compared to those tumors with lesser COX-2 staining (6.0 vs. 2.0 months; P=0.02). Patients with tumors with higher COX-2 expression also had numerically superior survival; however, the differences were not statistically significant. Twenty-four patients had tissue available for EGFR mutational analysis two (8%) of whom had an EGFR gene mutations detected only one of whom responded. The responding patient was a male, a never smoker with a squamous carcinoma and an exon 19 mutation. The second patient, also a male, had an adenocarcinoma and an exon 21 mutation. He was a heavy smoker and experienced progressive disease.

Gadgeel and colleagues examined the combination of gefitinib (250 mg QD) with celecoxib 400 mg BID in a phase II trial involving 27 patients with platinum-refractory NSCLC.75 Gefitinib is no longer available in North America due to lack of survival benefit seen in the IRESSA Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer (ISEL) phase III trial.76 Two patients (7%) had a partial response and six patients experienced stable disease. Median time to progression, median and 1 year survival were 2.2 months, 4.6 months and 16% respectively (Table 4). These results are similar to what was seen in the ISEL trial, in which single agent gefitinib was administered to more than 1000 NSCLC patients after failure of one or more chemotherapy regimens.76 There were no cardiovascular episodes noted and few grade 3 and 4 toxicities other than skin rash or diarrhea, side effects commonly associated with gefitinib alone. Unfortunately, these investigators did not have adequate tumor samples to assess COX-2 expression, EGFR mutation status or EGFR gene copy number.

Agarwala and colleagues also employed gefitinib (250 mg QD) with celecoxib (400 mg BID) in a phase II study of 31 chemotherapy naïve patients with advanced NSCLC.77 Two patients died of interstitial lung disease during treatment; there were three additional deaths that were not treatment related. Grade 3/4 toxicities were rare but included hepatitis, diarrhea, and skin rash. Neither EGFR gene mutation status nor copy number status was assessed. However, all five partial responses (16%) occurred in women with adenocarcinoma, two of whom were never smokers suggesting at least some of the responding patients harbored sensitizing EGFR mutations. Median duration of response, PFS and median survival were 5.7, 3.2 and 7.0 months respectively (Table 4).

Finally, O’Byrne and associates combined gefitinib with rofecoxib in a phase I/II study conducted in 45 patients with recurrent NSCLC that had failed one or two lines of chemotherapy.78 Rofecoxib, a more highly selective inhibitor of COX-2 than celecoxib, was administered at 12.5, 25 or 50 mg daily in conjunction with gefitinib (250 mg QD). Because the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of rofecoxib was not reached, the 50 mg cohort was expanded for efficacy evaluation. Among the 42 evaluable patients there was one complete and two partial responders (7%) and 12 patients (28.5%) with stable disease. Median time to progression was 1.8 months and median survival was 4.8 months (Table 4). Six month survival was 40.3%. Grade 3/4 toxicities were seen in five patients (dyspnea = 1; diarrhea = 2; rash = 2). One patient died of a cerebrovascular accident that was not considered study related. Unfortunately, the EGFR gene mutation or copy number was not assessed in this trial.

Collectively, these data indicate that if further study of the COX-2 inhibitor plus EGFR TKI strategy is to go forward, better patient selection is required guided perhaps by assessment of COX-2 protein expression using immunohistochemistry and/or measurement of urine metabolite of PGE2 coupled with an assessment of EGFR mutational status or perhaps EGFR copy number.79

Potential Eicosanoid Pathway Targets

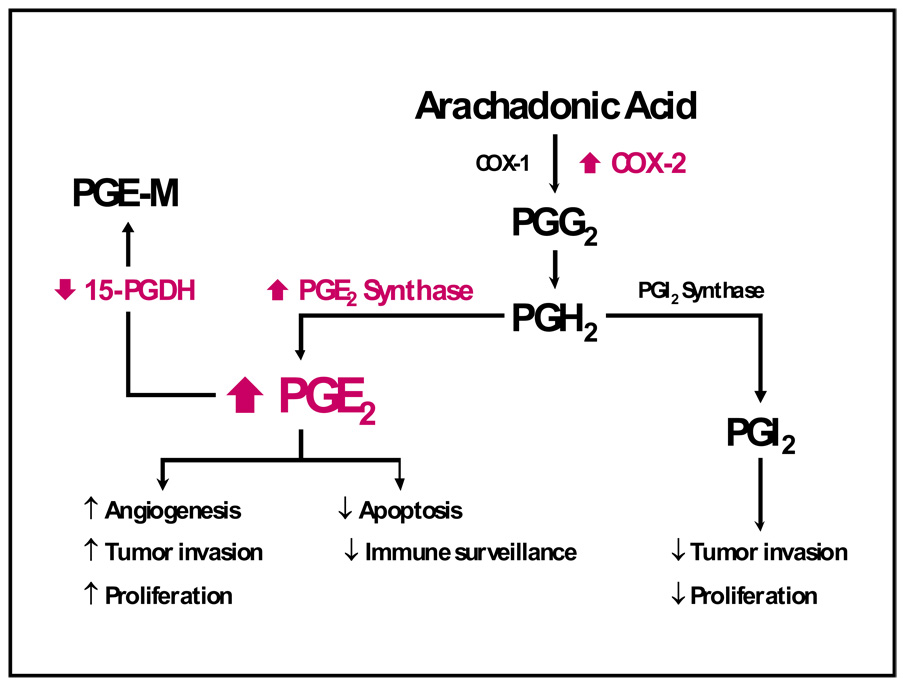

Although this review is focused primarily on the role of COX-2 inhibition in NSCLC, additional changes within the eicosanoid pathway occur in lung cancer that may contribute to increases in PGE2 levels (Figure 3). Such changes may render ineffective the strategy of using COX-2 inhibition alone. For example, the isomerization of the endoperoxide PGH2 to PGE2 is catalyzed by three different PGE synthases, namely, cytosolic PGE synthase (cPGES) and two membrane-bound PGE synthases, mPGES-1 and mPGES-2.80 cPGES and mPGES-2 are constitutive enzymes whereas mPGES-1 is mainly an inducible isomerase. Studies from disruption of the mPGES-1 gene in mice indicate key roles of mPGES-1-generated PGE2 in a number of pathological conditions such as inflammation, pain, fever, anorexia, atherosclerosis, stroke, and tumorigenesis.80 Recently, Yoshimatsu and colleagues compared amounts of mPGES in 19 paired samples of tumor and adjacent normal tissue taken from individuals with NSCLC.81 By immunoblot analysis, mPGES-1 was overexpressed in about 80% of the lung cancers. COX-2 was frequently up-regulated in these tumors as well. However, there were marked differences in the extent of up-regulation of mPGES-1 and COX-2 in individual tumors, indicating that the regulation of the two enzymes is not identical. Levels of mPGES-1 mRNA and protein were increased in NSCLC cell lines containing mutant Ras. A similar up-regulation of COX-2 has been reported with mutant Ras.8 Of note, TNF-α induced mPGES-1 and COX-2 in NSCLC cell lines, but there was no effect on the expression of either enzyme in a nontumorigenic bronchial epithelial cell line. These data clearly link the EGFR and eicosanoid pathways and indicated that both cellular transformation and cytokines contribute to the up-regulation of mPGES-1 in NSCLC. These findings further suggest that mPGES-1 is a potential therapeutic target in NSCLC. Interestingly, oxacillin and dyphylline act as competitive inhibitors of mPGES-1.82 This novel inhibitory activity against mPGES-1 may provide valuable insight for the design of more, potent mPGES-1 inhibitors.82,83

Figure 3.

The increased understanding that selective COX-2 inhibitors are not free of unwanted side effects (particularly on renal and cardiovascular systems) have led to a reevaluation of other potential targets in the PG synthesis pathway downstream of COX for treatment and/or prevention of lung cancers, including PGE synthases and 15-PGDH. Another attractive target for inhibition of the activity of the PG synthesis pathway is inhibition of downstream receptor signaling.

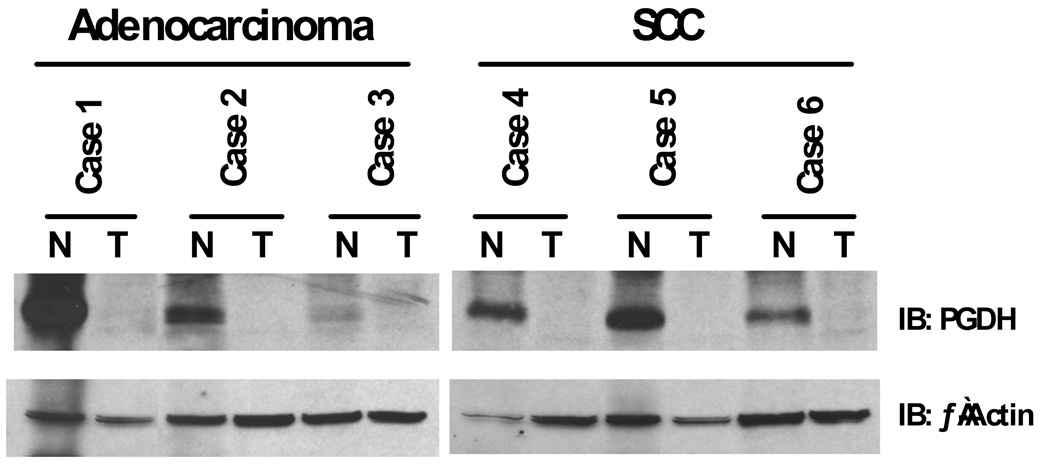

Recently, 15-hydroxyprostoglandin dehydroxygenase (PGDH), the rate-limiting enzyme responsible for PGE2 catabolism, has been shown to be downregulated in lung cancers.84–86 Our group reported a dramatic down-regulation of PGDH protein in NSCLC cell lines and in resected human tumors when compared with matched normal lung (Figure 4).84 Affymetrix array analysis of 10 normal lung tissue samples and 49 resected lung tumors revealed a much lower expression of PGDH transcripts in all NSCLC histologic groups. These findings suggest a possible tumor suppressor activity for PDGH similar to that proposed in gastrointestinal malignancies.87,88 We also found that erlotinib treatment could increase PDGH expression in a subset of NSCLC cell lines.84 This effect may be due in part to an inhibition of the ERK pathway as treatment with the MEK inhibitor U0126 mimicked the erlotinib results. Using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR we found that the transcript levels of ZEB1 and Slug transcriptional repressors were dramatically reduced in a responsive cell line upon EGFR and MEK/ERK inhibition. The Slug protein, but not ZEB1, bound to the PDGH promoter and repressed transcription. This effect was reversible in a subset of NSCLC upon treatment with an EGFR TKI. The fact that erlotinib increases PDGH expression may in part account for its activity in lung cancers that do not harbor sensitizing EGFR mutations. Interestingly, mutations in 15-PGDH have recently been reported to cause primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy.89 These findings suggest high PGE2 levels may also explain some of the classical albeit somewhat rare clinical findings associated with intrathoracic malignancies such as clubbing and periostosis.90

Figure 4.

Total RNA and protein were isolated from six individual human non-small cell lung cancer tissues and matched normal mucosa. Equal amounts of RNA and protein were analyzed for 15-PGDH expression. SCC = squamous cell carcinoma. N, normal lung; T, tumor tissue. 84

The thiazolidinediones, as well as histone deacetylase inhibitors and steroids, also can increase PGDH expression in selected lung cancer cell lines.91,92 The clinical relevance of this observation is perhaps best illustrated by a recent report suggesting thiazolidinedione use among male diabetic patients aged 40 years and older was associated with a decreased risk of developing lung cancer.93 A similar risk reduction was not observed for prostate or colon cancers. Dubinett has suggested that this targeted intervention may promote the degradation of the procarcinogenic PGE2 that in turn leads to a more favorable pulmonary environment in the lung at risk for carcinogenesis. For example, a decline in PGE2 due to increased PGDH related degradation without alteration of PGI2 levels could favor antitumorigenic effects as well as limit cardiovascular toxicities that might be associated with COX-2 inhibitors.92 Of note, thiazolidinediones also synergize with platinum-based drugs in several different cancers both in vitro and using transplantable and chemically induced “spontaneous” tumor models.94 The effect appears to be due in part to these agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) mediated downregulation of metallothioneins, proteins that have been shown to be involved in resistance to platinum-based therapy.94 Parenthetically, mPGES-1 inhibition not only decreases proinflammatory PGE2 but also up-regulates anti-inflammatory PPARγ, which in turn suppresses COX-2 and mPGES-1 expression and PGE2 production.95 Recently, the combination of rosiglitazone and carboplatin has shown promise in the treatment of refractory NSCLC.96

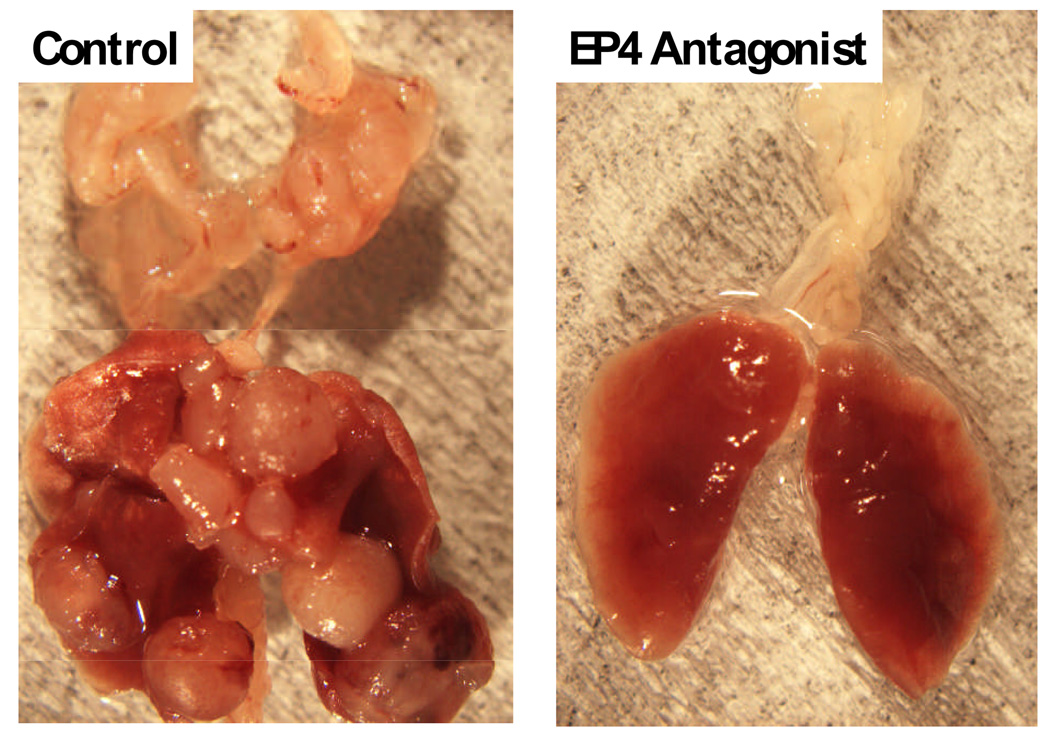

Finally prostanoids exert their actions through G protein-coupled receptors with seven transmembrane domains.97 There are eight types and subtypes of prostanoid receptors that are encoded by different genes but as a whole constitute a subfamily in the superfamily of the rhodopsin-type receptors. Among prostanoids, PGE2 has the most receptors including EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4, defined on the basis of their pharmacological profiles. We and others have found that antagonism of the EP4 receptor with either AH23848 or ONO-AE3-208 directly inhibits the proliferation of tumor cells and tumor metastasis (Figure 5).98,99 These data suggest inhibition of EP receptors may play a future role in the treatment of several malignancies including breast and colon cancer as well as lung cancer.98,99

Figure 5.

Photograph of the lungs from mice after tail vein injection of 3LL cells with or without treatment of the host with the EP4 antagonist ONO-AE3-208.99

Conclusions

There is now abundant preclinical and clinical data to indicate PGE2 is involved in the pathogenesis of NSCLC.100 Modulation of this bioactive prostanoid represents a reasonable therapeutic target in this common malignancy. Strategies designed to abrogate the biological effects of PGE2 such as COX-2 inhibition may yet prove useful in the proper biological context. However, the prolonged use of high dosages of COX-2 selective inhibitors has been associated with unacceptable cardiovascular side effects. Two trials were closed early due to serious adverse events.53,72 Moreover, two large chemopreventive trials found a nearly 2-fold increase in cardiovascular risk with celecoxib 200 mg or 400 mg BID or 400 mg daily compared to placebo.101 This risk needs to be carefully considered in patients with NSCLC who already may have multiple cardiac comorbidities. Thus it is crucial to develop more effective chemotherapeutic agents with less cardiovascular toxicity. Indeed COX-2 inhibition is not without significant toxicities. Strategies designed to modulate mPGES-1 or 15-PGDH activity or block receptor signaling may prove beneficial in the treatment of lung cancer and also serve to bypass some of the undesirable toxicities of selective COX-2 inhibitors. These future studies will require careful selection and monitoring of patients to maximize potential for efficacy and to ensure optimal patient safety.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forgacs E, Zochbauer-Muller S, Olah E, et al. Molecular genetic abnormalities in the pathogenesis of human lung cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2001;7:6–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03032598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JR, Dubois RN. Cyclooxygenase as a target in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4266s–4269s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-040014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krysan K, Reckamp KL, Sharma S, et al. The potential and rationale for COX-2 inhibitors in lung cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2006;6:209–220. doi: 10.2174/187152006776930882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Dubois RN. Prostaglandins and cancer. Gut. 2006;55:115–122. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ermert L, Dierkes C, Ermert M. Immunohistochemical expression of cyclooxygenase isoenzymes and downstream enzymes in human lung tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1604–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hida T, Yatabe Y, Achiwa H, et al. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase 2 occurs frequently in human lung cancers, specifically in adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3761–3764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soslow RA, Dannenberg AJ, Rush D, et al. COX-2 is expressed in human pulmonary, colonic, and mammary tumors. Cancer. 2000;89:2637–2645. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001215)89:12<2637::aid-cncr17>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff H, Saukkonen K, Anttila S, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4997–5001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brabender J, Park J, Metzger R, et al. Prognostic significance of cyclooxygenase 2 mRNA expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Annals of Surgery. 2002;235:440–443. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khuri FR, Wu H, Lee JJ, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression is a marker of poor prognosis in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laga AC, Zander DS, Cagle PT. Prognostic significance of cyclooxygenase 2 expression in 259 cases of non-small cell lung cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1113–1117. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1113-PSOCEI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josephy PD, Chiu AL, Eling TE. Prostaglandin H synthase-dependent mutagenic activation of benzidine in a Salmonella typhimurium Ames tester strain possessing elevated N-acetyltransferase levels. Cancer Res. 1989;49:853–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley DJ, Mestre JR, Subbaramaiah K, et al. Benzo[a]pyrene up-regulates cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in oral epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:795–799. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moraitis D, Du B, De Lorenzo MS, et al. Levels of cyclooxygenase-2 are increased in the oral mucosa of smokers: evidence for the role of epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligands. Cancer Res. 2005;65:664–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masferrer JL, Leahy KM, Koki AT, et al. Antiangiogenic and antitumor activities of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1306–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman AP, Williams CS, Sheng H, et al. Meloxicam inhibits the growth of colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:2195–2199. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.12.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hida T, Kozaki K, Muramatsu H, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor induces apoptosis and enhances cytotoxicity of various anticancer agents in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2006–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hida T, Kozaki K-i, Ito H, et al. Significant growth inhibition of human lung cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo by the combined use of a selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor, JTE-522, and conventional anticancer agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2443–2447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheng H, Shao J, Kirkland SC, et al. Inhibition of human colon cancer cell growth by selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;99:2254–2259. doi: 10.1172/JCI119400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams CS, Tsujii M, Reese J, et al. Host cyclooxygenase-2 modulates carcinoma growth [see comments] J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1589–1594. doi: 10.1172/JCI9621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim ES, Hong WK, Lee JJ, et al. A randomized double-blind study of the biological effects of celecoxib as a chemopreventive agent in current and former smokers. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1501. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinbach G, Lynch PM, Phillips RK, et al. The effect of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1946–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Relation to the Expression of COX-2. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2131–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gridelli C, Gallo C, Ceribelli A, et al. Factorial phase III randomised trial of rofecoxib and prolonged constant infusion of gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the GEmcitabine-COxib in NSCLC (GECO) study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:500–512. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baron JA, Sandler RS, Bresalier RS, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib: final analysis of the APPROVe trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1756–1764. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edelman MJ, Watson D, Wang X, et al. Eicosanoid modulation in advanced lung cancer: cyclooxygenase-2 expression is a positive predictive factor for celecoxib + chemotherapy. Cancer and Leukemia Group B Trial 30203. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:848–855. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR., Jr Leukotrienes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1841–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avis IM, Jett M, Boyle T, et al. Growth Control of Lung Cancer by Interruption of 5-Lipoxygenase-mediated Growth Factor Signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:806–813. doi: 10.1172/JCI118480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rioux N, Castonguay A. Inhibitors of lipoxygenase: a new class of cancer chemopreventive agents. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1393–1400. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.8.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fossella F, Pereira JR, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized, multinational, phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TAX 326 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3016–3024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3210–3218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Achiwa H, Yatabe Y, Hida T, et al. Prognostic significance of elevated cyclooxygenase 2 expression in primary, resected lung adenocarcinomas. Clinical Cancer Research. 1999;5:1001–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gadgeel SM, Wozniak A, Ruckdeschel JC, et al. Phase II study of docetaxel and celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in elderly or poor performance status (PS2) patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1293–1300. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818b194e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors. JAMA. 2001;286:954–959. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.8.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton JD, Badine E, El-Sayah D, et al. Update of a phase I/II trial of carboplatin/gemcitabine plus escalating doses of celecoxib for first-line treatment of stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:7339. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simon R, Maitournam A. Evaluating the efficiency of targeted designs for randomized clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6759–6763. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altorki NK, Keresztes RS, Port JL, et al. Celecoxib, a selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor, enhances the response to preoperative paclitaxel and carboplatin in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2645–2650. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pisters KM, Kris MG, Gralla RJ, et al. Pathologic complete response in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer following preoperative chemotherapy: implications for the design of future non-small-cell lung cancer combined modality trials. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1757–1762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.9.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Subbaramaiah K, Hart JC, Norton L, et al. Microtubule-interfering agents stimulate the transcription of cyclooxygenase-2. Evidence for involvement of ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen- activated protein kinase pathways. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14838–14845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altorki NK, Port JL, Zhang F, et al. Chemotherapy induces the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4191–4197. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milella M, Ceribelli A, Gelibter A, et al. Celecoxib combined with fixed dose-rate Gemcitabine (FDR-Gem)/CDDP as induction chemotherapy for stage III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7324. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18:2354–2362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Csiki I, Morrow JD, Sandler A, et al. Targeting cyclooxygenase-2 in recurrent non-small cell lung cancer: a phase II trial of celecoxib and docetaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6634–6640. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piper PJ, Vane JR, Wyllie JH. Inactivation of prostaglandins by the lungs. Nature. 1970;225:600–604. doi: 10.1038/225600a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seyberth HW, Sweetman BJ, Frolich JC, et al. Quantifications of the major urinary metabolite of the E prostaglandins by mass spectrometry: evaluation of the method's application to clinical studies. Prostaglandins. 1976;11:381–397. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphey LJ, Williams MK, Sanchez SC, et al. Quantification of the major urinary metabolite of PGE(2) by a liquid chromatographic/mass spectrometric assay: determination of cyclooxygenase-specific PGE(2) synthesis in healthy humans and those with lung cancer. Anal Biochem. 2004;334:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gross ND, Boyle JO, Morrow JD, et al. Levels of prostaglandin E metabolite, the major urinary metabolite of prostaglandin E2, are increased in smokers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6087–6093. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nugent FW, Mertens WC, Graziano S, et al. Docetaxel and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition with celecoxib for advanced non-small cell lung cancer progressing after platinum-based chemotherapy: a multicenter phase II trial. Lung Cancer. 2005;48:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider BJ, Kalemkerian GP, Kraut MJ, et al. Phase II study of celecoxib and docetaxel in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with progression after platinum-based therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1454–1459. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818de1d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lorenz M, Slaughter HS, Wescott DM, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 is essential for normal recovery from 5-fluorouracil-induced myelotoxicity in mice. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1494–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gasparini G, Meo S, Comella G, et al. The combination of the selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib with weekly paclitaxel is a safe and active second-line therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: a phase II study with biological correlates. Cancer J. 2005;11:209–216. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Esteban E, Gonzalez de Sande L, Fernandez Y, et al. Prospective randomised phase II study of docetaxel versus paclitaxel administered weekly in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1640–1647. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aisner J. Targeting COX-2/PG-E2 with a COX-2 inhibitor in combination with chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: are we ready for phase III? Cancer J. 2005;11:201–203. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lilenbaum R, Socinski MA, Altorki NK, et al. Randomized phase II trial of docetaxel/irinotecan and gemcitabine/irinotecan with or without celecoxib in the second-line treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4825–4832. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gradilone A, Silvestri I, Scarpa S, et al. Failure of apoptosis and activation on NFkappaB by celecoxib and aspirin in lung cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:823–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gradilone A, Pulcinelli FM, Lotti LV, et al. Celecoxib Induces MRP-4 in Lung Cancer Cells: Therapeutic Implications. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4318–4320. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tian Q, Zhang J, Tan TM, et al. Human multidrug resistance associated protein 4 confers resistance to camptothecins. Pharm Res. 2005;22:1837–1853. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-7595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Argiris A, Kut V, Luong L, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of docetaxel, irinotecan, and celecoxib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2006;24:203–212. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-3259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang J, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell. 2008;14:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krysan K, Lee JM, Dohadwala M, et al. Inflammation, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:107–110. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181630ece. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomson S, Buck E, Petti F, et al. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition Is a Determinant of Sensitivity of Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma Cell Lines and Xenografts to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibition. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9455–9462. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Witta SE, Gemmill RM, Hirsch FR, et al. Restoring E-cadherin expression increases sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2006;66:944–950. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dohadwala M, Luo J, Zhu L, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer cyclooxygenase-2-dependent invasion is mediated by CD44. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20809–20812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100140200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dohadwala M, Batra RK, Luo J, et al. Autocrine/paracrine prostaglandin E2 production by non-small cell lung cancer cells regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 and CD44 in cyclooxygenase-2-dependent invasion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50828–50833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210707200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dohadwala M, Yang SC, Luo J, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent regulation of E-cadherin: prostaglandin E(2) induces transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and snail in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5338–5345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reckamp KL, Krysan K, Morrow JD, et al. A phase I trial to determine the optimal biological dose of celecoxib when combined with erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3381–3388. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fidler MJ, Argiris A, Patel JD, et al. The potential predictive value of cyclooxygenase-2 expression and increased risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with erlotinib and celecoxib. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2088–2094. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Camidge R, Reigner B, Cassidy J, et al. Significant Effect of Capecitabine on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Warfarin in Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4719–4725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gadgeel SM, Ruckdeschel JC, Heath EI, et al. Phase II study of gefitinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI), and celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor, in patients with platinum refractory non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:299–305. doi: 10.1097/01.JTO.0000263712.61697.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Agarwala A, Fisher W, Bruetman D, et al. Gefitinib plus celecoxib in chemotherapy-naive patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer: a phase II study from the Hoosier Oncology Group. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:374–379. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181693869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O'Byrne KJ, Danson S, Dunlop D, et al. Combination therapy with gefitinib and rofecoxib in patients with platinum-pretreated relapsed non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3266–3273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hirsch FR, Dziadziuszko R, Thatcher N, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor immunohistochemistry: comparison of antibodies and cutoff points to predict benefit from gefitinib in a phase 3 placebo-controlled study in advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1114–1121. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Samuelsson B, Morgenstern R, Jakobsson P-J. Membrane prostaglandin E synthase-1: A novel therapeutic target. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:207–224. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yoshimatsu K, Altorki NK, Golijanin D, et al. Inducible prostaglandin E synthase is overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2669–2674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim WI, Choi KA, Do HS, et al. Expression and purification of human mPGES-1 in E. coli and identification of inhibitory compounds from a drug-library. BMB Rep. 2008;41:808–813. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.11.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.AbdulHameed MDM, Hamza A, Liu J, et al. Human Microsomal Prostaglandin E Synthase-1 (mPGES-1) Binding with Inhibitors and the Quantitative Structure−Activity Correlation. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2008;48:179–185. doi: 10.1021/ci700315c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang L, Amann JM, Kikuchi T, et al. Inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling elevates 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5587–5593. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huang G, Eisenberg R, Yan M, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is a target of hepatocyte nuclear factor 3beta and a tumor suppressor in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5040–5048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hughes D, Otani T, Yang P, et al. NAD+-dependent 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase regulates levels of bioactive lipids in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:241–249. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Backlund MG, Mann JR, Holla VR, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is down-regulated in colorectal cancer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3217–3223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411221200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ding Y, Tong M, Liu S, et al. NAD+-linked 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH) behaves as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:65–72. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Uppal S, Diggle CP, Carr IM, et al. Mutations in 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase cause primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Nat Genet. 2008;40:789–793. doi: 10.1038/ng.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Coggins KG, Coffman TM, Koller BH. The Hippocratic finger points the blame at PGE2. Nat Genet. 2008;40:691–692. doi: 10.1038/ng0608-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hazra S, Batra RK, Tai HH, et al. Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone decrease prostaglandin E2 in non-small-cell lung cancer cells by up-regulating 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1715–1720. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dubinett SM, Mao JT, Hazra S. Focusing Downstream in Lung Cancer Prevention: 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin Dehydrogenase. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:223–225. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Govindarajan R, Ratnasinghe L, Simmons DL, et al. Thiazolidinediones and the risk of lung, prostate, and colon cancer in patients with diabetes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1476–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Girnun GD, Naseri E, Vafai SB, et al. Synergy between PPAR[gamma] Ligands and Platinum-Based Drugs in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kapoor M, Kojima F, Qian M, et al. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 deficiency is associated with elevated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma: regulation by prostaglandin E2 via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5356–5366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Girnun GD, Chen L, Silvaggi J, et al. Regression of Drug-Resistant Lung Cancer by the Combination of Rosiglitazone and Carboplatin. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6478–6486. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bos CL, Richel DJ, Ritsema T, et al. Prostanoids and prostanoid receptors in signal transduction. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1187–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ma X, Kundu N, Rifat S, et al. Prostaglandin E Receptor EP4 Antagonism Inhibits Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2923–2927. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang L, Huang Y, Porta R, et al. Host and direct antitumor effects and profound reduction in tumor metastasis with selective EP4 receptor antagonism. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9665–9672. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Backlund MG, Amann JM, Johnson DH. Novel strategies for the treatment of lung cancer: modulation of eicosanoids. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:825–827. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1071–1080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]