Abstract

Our previous studies have shown that diabetes in the male streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rat is characterized by a decrease in circulating testosterone and concomitant increase in estradiol levels. Interestingly, this increase in estradiol levels persists even after castration, suggesting extra-testicular origins of estradiol in diabetes. The aim of the present study was to examine whether other target organs of diabetes may be sources of estradiol. The study was performed in male Sprague-Dawley non-diabetic (ND), STZ-induced diabetic (D) and STZ-induced diabetic castrated (Dcas) rats (n=8-9/group). 14 weeks of diabetes was associated with decreased testicular (ND, 26.3±4.19; D, 18.4±1.54; P<0.05), but increased renal (ND, 1.83±0.92; D, 7.85±1.38; P<0.05) and ocular (D, 23.4±3.66; D, 87.1±28.1; P<0.05) aromatase activity. This increase in renal (Dcas, 6.30±1.25) and ocular (Dcas, 62.7±11.9) aromatase activity persisted after castration. The diabetic kidney also had increased levels of tissue estrogen (ND, 0.31 ±0.01; D, 0.51±0.11; Dcas, 0.45±0.08) as well as estrogen receptor alpha protein expression (ND, 0.63±0.09; D, 1.62±0.28; Dcas, 1.38±0.20). These data suggest that in male STZ-induced diabetic rats, tissues other than the testis may become sources of estradiol. In particular, the diabetic kidney appears to produce estradiol following castration, a state that is associated with a high degree or renal injury. Overall, our data provides evidence for the extra-testicular source of estradiol that in males, through an intracrine mechanism, may contribute to the development and/or progression of end-organ damage associated with diabetes.

Keywords: diabetes, aromatase, estrogen, testosterone, estrogen receptor, androgen receptor, testis, kidney, eye

1. Introduction

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in men is associated with decreased circulating levels of total and free testosterone [1-3]. Studies in experimental models of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in males have confirmed these observations [4-7]. Some of these studies have also shown that this diabetes-associated decrease in testosterone in males is accompanied by a concomitant increase in estradiol levels [4,5,7]. Although associations between changes in sex hormone levels and diabetes have been reported, it is unclear whether decreased testosterone and/or increased estradiol levels are a cause or consequence of diabetes in men?

Interestingly, studies from our as well as laboratories of others have shown that estradiol levels in the streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic male rat remain elevated even after castration and thus removal of the primary source of the hormone [4,7]. These observations suggest that estradiol, at least in diabetes, may be produced in organs other than the testes. Indeed, adrenal glands have been shown to produce significant amounts of the inactive precursor steroid, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione (4-DIONE), which are converted into testosterone and estradiol in peripheral tissues [8,9]. The rate of formation of sex steroids is dependent on the level of expression of androgen and estrogen-synthesizing enzymes in each tissue. In particular, estrogens are converted to androgens catalyzed by aromatase cytochrome P450 in several non-reproductive tissues, including the brain [10], adrenal cortex [11], skeletal muscle [12], prostate gland [9], adipose tissue [13], retina of the eye [14] and the developing kidney [15,16]. However, little is known about the expression of aromatase in non-reproductive tissues in diabetes. Thus, the aim of the present study was to examine the expression and activity of aromatase in peripheral target tissues in diabetes as a potential explanation of the paradoxical elevated levels of estradiol despite the decrease in testosterone levels in diabetes. Given our previous observations that the reduction in testosterone and increase in estradiol correlated with the degree of renal disease associated with diabetes [7], we were specifically interested in examining the expression of aromatase in the diabetic kidney.

2. Experimental

2.1 Animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Madison, WI, 12 weeks of age) were maintained on regular rat chow and water ad libitum. The rats were randomly divided into three treatment groups: non-diabetic (n=8), streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic (n=9) and STZ-induced diabetic that were castrated at 10 weeks of age (n=8). Castration was performed by the supplier (Harlan). Diabetes was induced, after an overnight fast, by a single i.p. injection of 55 mg/kg streptozotocin (STZ, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5). Non-diabetic rats received 0.1 M citrate buffer only. Throughout the study (14 weeks), all diabetic rats received insulin, s.c. every 3 days (2-4 U, Lantus, Aventis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Kansas City, MO) to maintain blood glucose levels between 300-450 mg/dl (measured using the OneTouch Ultra glucometer), promote weight gain and prevent mortality. The rats were placed into metabolic cages every 4 weeks for 24 hours for collection of urine for analysis of urine albumin excretion. After 14 weeks of treatment, the rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (40 mg/kg, ip) and blood collected via cardiac puncture for measurement of plasma sex hormone levels. The testes, adrenal glands, kidneys and eyes were dissected, weighed and either immersion fixed in histochoice (Amresco, Solon, OH) for immunohistochemical analysis or snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for Western blotting. All experiments were performed according to the guidelines recommended by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Georgetown University and the University of Mississippi Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Plasma hormone level

Plasma testosterone, estradiol and androstenedione levels were measured by ELISA (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.3. Tissue hormone levels

For measurement of renal cortical and testicular levels of testosterone and estradiol, tissues were extracted according to the method developed by Vom Saal et al [17]. Briefly, 40mg samples of the frozen renal cortex were homogenized in a PBS buffer containing 0.1% of gelatin then precipitated with ethyl acetate/chloroform (4:1). The samples were air dried and testosterone and estradiol levels measured using the Coat-a-count radioimmunoassay (Siemens Medical Solutions diagnostics, Deerfield, IL).

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections (4μm) were incubated with 10% non-immune goat serum to block non-specific immunolabeling. Antigen retrieval was performed on slides incubated for androgen receptor (AR) only. Sections were then incubated with antisera against aromatase (1:200; rabbit polyclonal; cat no. 18995; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), AR (1:800; rabbit polyclonal; cat. no. sc-815; Santa Cruz Biotech., Santa Cruz, CA) or estrogen receptor ERα (1:2,000; rabbit polyclonal, cat. no. 06-935; Upstate) at 4°C overnight. After washing with phosphate buffered saline, sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit, anti-mouse or anti-goat IgG (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark), followed by incubation with the avidin-biotin complex (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Positive immunoreaction was detected after incubation with 3, 3-diaminobenzidine and counterstaining with Mayer's hematoxylin. Sections incubated with 10% goat serum instead of the primary antiserum were used as negative controls.

2.5. Western blotting

Homogenized protein samples (30μg) were denatured at 95°C for 10 minutes, loaded onto SDS-PAGE precast gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were incubated first with 5% non-fat milk and then with antisera against aromatase (1:200), AR (1:1,000; rabbit polyclonal; cat. no. 06-680; Upstate, Temecula, CA) or ERα (1:1,000) at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed, incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and proteins visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). All membranes were then stripped and re-probed with an antibody against β-actin (1:3,000; mouse monoclonal; cat. no. 4970; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). The densities of specific bands were quantitated by densitometry using the Scion Image beta (version 4.02) software and normalized to the total amount of protein loaded in each well following densitometric analysis of gels stained for β-actin.

2.6. Aromatase activity

Frozen samples of testis, kidney or retina of the eye were incubated with 4.0 μM, 3[H]1-β androstenedione as the substrate for 1 hour in a shaking water bath at 37°C. Aromatase activity was determined by the 3[H2O] release assay where aromatization of the substrate was isolated from the aqueous phase of the reaction mixture as previously described [18]. The aromatase activity was expressed in fmol/h of incubation/mg protein after measurement of the protein content of each sample using the Lowry method [19].

2.7. Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean±SEM and were analyzed using the student's t-test (Prism 4, Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA) or a one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls posthoc comparison test when the Dcas group was included in the analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Blood glucose and body weight

Table 1 shows that the D animals exhibited a 386% increase in blood glucose levels and 36% decrease in body weight (Table 1). Castration had no further influence on these parameters (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolic parameters and steroid hormone levels

| Parameters | ND | D | Dcas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose (mg/dl) | 90.1±1.85 | 438±12.5*** | 459±18.2*** |

| Body weight (g) | 428±9.24 | 275±39.3** | 256±23.0*** |

| Plasma testosterone (ng/ml) | 3.8±0.29 | 1.3±0.52* | 0.046±0.029***,## |

| Plasma estradiol (pg/ml) | 1.6±0.81 | 3.1±0.41* | 2.8±0.27* |

| Plasma 3-DIONE (ng/ml) | 0.33±0.05 | 0.32±0.08 | 0.15±0.02*,# |

| Testicular testosterone (ng/mg protein) | 34±4.4 | 9.3±1.3*** | N/A |

| Testicular estradiol (ng/mg protein) | 7.8±1.9 | 8.4±2.3 | N/A |

| Renal testosterone (ng/mg protein) | 1.3±0.17 | 1.4±0.47 | 0.34±0.11 |

| Renal estradiol (pg/mg protein) | 0.31±0.014 | 0.51±0.11* | 0.45±0.08* |

Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

P<0.05 vs ND;

P<0.01 vs ND;

P<0.001 vs ND

P<0.05 vs D;

P<0.01 vs D;

P<0.001 vs D

Abbreviations: ND, non-diabetic; D, diabetic; Dcas, diabetic castrated; 3-DIONE, androstenedione

3.2. Circulating and tissue sex hormone levels

Confirming our previous report [7], D was associated with a 66% decrease in plasma testosterone and a 94% increase in estradiol levels compared with ND animals (Table 1). Castration further decreased plasma testosterone levels compared with intact D animals, but no effects of castration were observed with respect to estradiol levels, i.e. the D-associated increase in estradiol levels persisted even after castration (Table 1).

Similar to testosterone in the circulation, D was associated with a 73% decrease in testicular levels of testosterone, but no differences in renal testosterone levels were observed between the ND and D animals (Table 1). Castration however decreased renal cortical testosterone levels by 75% compared with the intact D (Table 1). Testicular estradiol levels remained unchanged with diabetes, while renal cortical estradiol levels increased by 65% compared with ND animals. Castration had no further effect on renal cortical estradiol levels.

No differences in androstenedione levels were observed between the ND and D animals (Table 1). Castration was associated with a 53% decrease in androstenedione levels compared with both ND and D animals.

3.3. Aromatase activity and protein expression

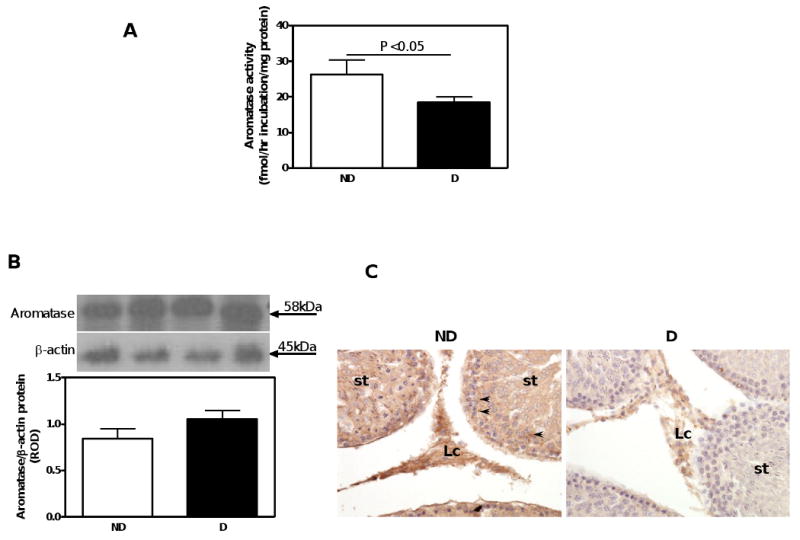

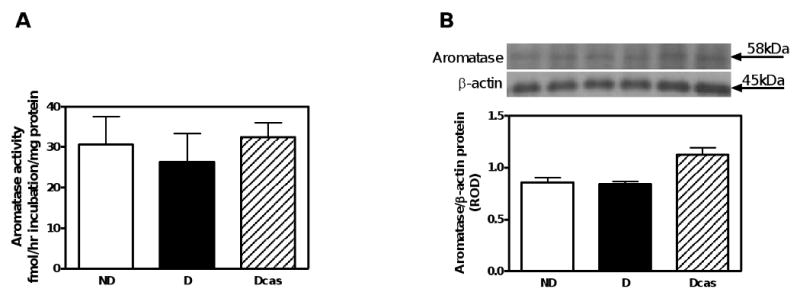

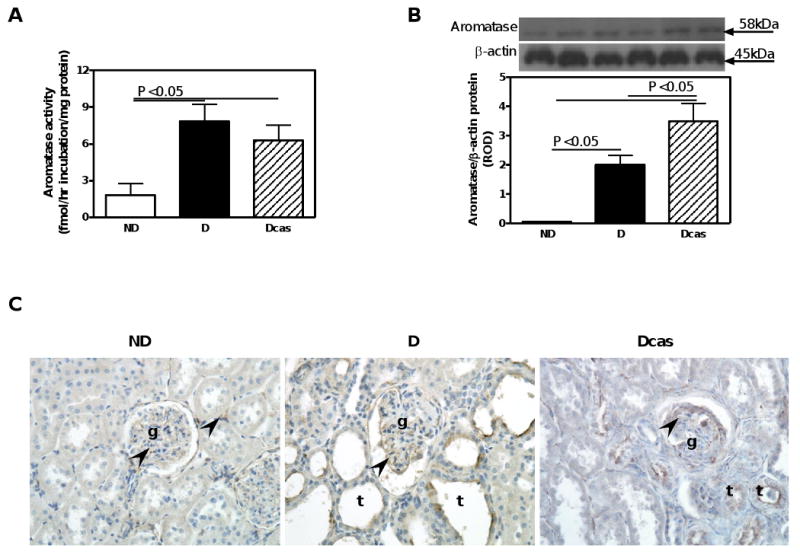

There was a 30% reduction in aromatase activity in the testes of D compared with ND animals (Fig. 1A), despite no differences in aromatase protein expression, as measured by Western blotting (Fig. 1B). Aromatase protein was immunolocalized to Sertoli and Leydig cells (Fig. 1C). No differences in either aromatase activity (Fig. 2A) or its protein expression (Fig. 2B) were observed in the adrenal gland. Aromatase activity (Fig. 3A) as well as aromatase protein expression (Fig. 3B) was increased by 330% and 3,788%, respectively, in the renal cortex of D compared with ND animals. The increase in aromatase protein expression was even more pronounced in Dcas animals, though castration had no apparent effect in aromatase activity compared with intact D animals. In the ND kidney, aromatase protein was immunolocalized to the glomerular and peritubular endothelium, albeit with weak intensity of staining (Fig. 3C). D, in both intact and castrated animals, was associated with an overall increase in the intensity of immunostaining for aromatase with staining being evident in the glomerular endothelium and dilated and/or atrophying renal tubules (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 1.

Aromatase activity, protein expression and immunolocalization in the testis. A. Aromatase activity. B. Aromatase protein expression. Top panel, representative immunoblot of aromatase protein expression. Bottom panel, densitometric scans in relative optical density (ROD) expressed as a ratio of aromatase/β-actin. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. C. Aromatase immunolocalization. Abbreviations and symbols: seminiferous tubule (st); Leydig cell (Lc); cytoplasm of Sertoli cells (arrow heads). Original magnification ×400.

Fig. 2.

Aromatase activity and protein expression in the adrenal gland. A. Aromatase activity. B. Aromatase protein expression. Top panel, representative immunoblot of aromatase protein expression. Bottom panel, densitometric scans in relative optical density (ROD) expressed as a ratio of aromatase/β-actin. Data are expressed as mean±SEM.

Fig. 3.

Aromatase activity, protein expression and immunolocalization in the kidney. A. Aromatase activity. B. Aromatase protein expression. Top panel, representative immunoblot of aromatase protein expression. Bottom panel, densitometric scans in relative optical density (ROD) expressed as a ratio of aromatase/β-actin. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. C. Aromatase immunolocalization. Abbreviations and symbols: glomerulus (g); tubules (t); endothelial cell (arrow heads). Original magnification ×400.

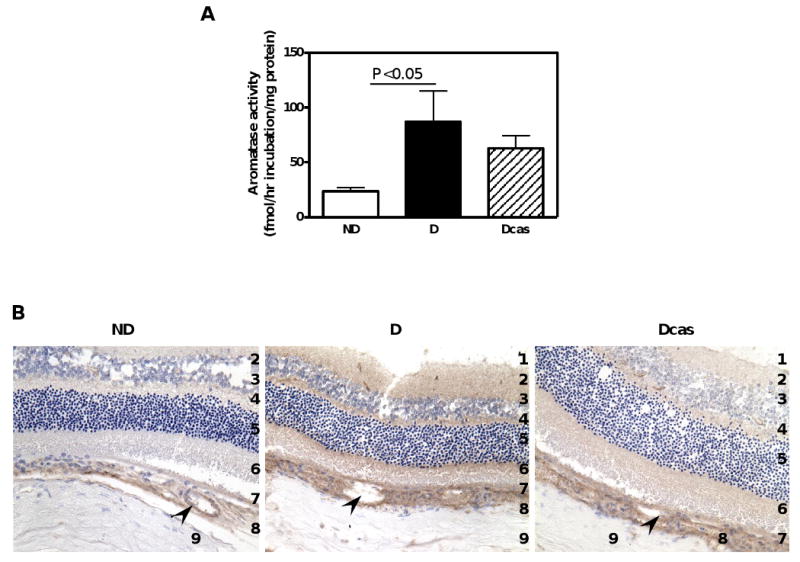

Surprisingly, aromatase activity was also dramatically increased in the retina of the eye. Diabetes was associated with a 271% increase in retinal aromatase activity compared with ND (Fig. 4A), with no further changes in the Dcas compared with D (note: we have no data on aromatase protein expression due to insufficient tissue sample). Immunohistochemistry reveled aromatase protein localization most notably in the capillaries of the choroid (Fig. 4B), with the apparent intensity of immunolocalization being increased in both intact and castrated D compared with ND rats.

Fig. 4.

Aromatase activity and immunolocalization in the eye. A. Aromatase activity. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. B. Aromatase immunolocalization. Abbreviations and symbols: 1. ganglion cell layer; 2. inner plexiform layer; 3. inner nuclear layer; 4. outer plexiform layer; 5. outer nuclear layer; 6. rods and cones; 7. pigmented epithelium; 8. choroid; 9. sclera; capillaries (arrow heads).

3.4. Androgen receptor expression

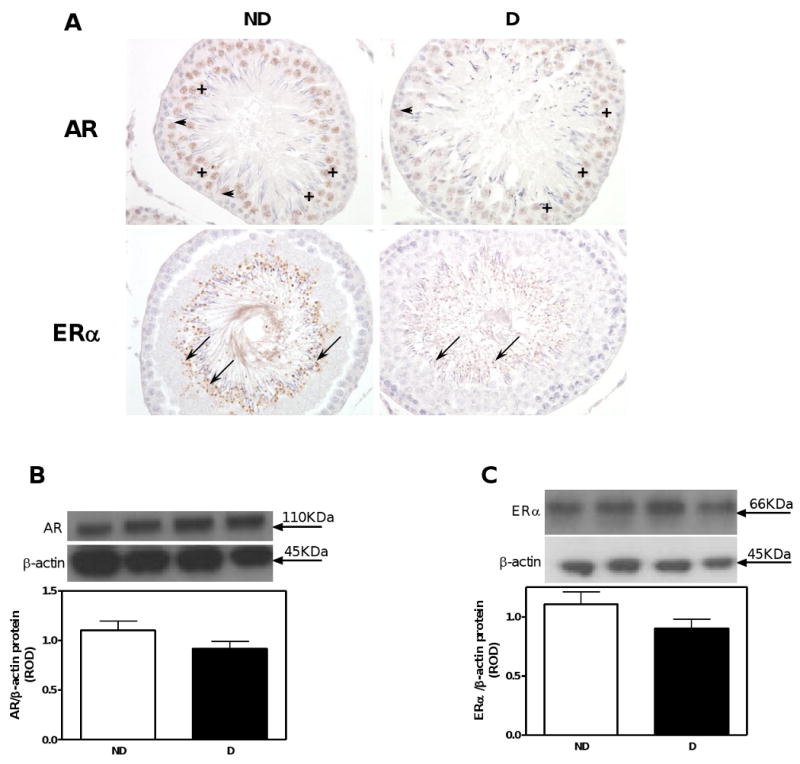

In the testis, androgen receptors were immunolocalized to Sertoli cells and spermatogonia, with an apparent reduction in the intensity of immunostaining in D compared with ND animals (Fig. 5A). No differences in androgen receptor protein expression, as measured by Western blotting were observed (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

AR and ERα immunolocalization and protein expression in the testis. A. AR and ERα immunolocalization. Symbols: Sertoli cells (arrow heads); spermatogonia (+); spermatids (arrows). Original magnification ×400. B. AR protein expression. C. ERα protein expression. Top panel in B and C, representative immunoblot of AR and ERα, respectively. Bottom panel in B and C, densitometric scans in relative optical density (ROD) expressed as a ratio of AR or ERα/β-actin. Data are expressed as mean±SEM.

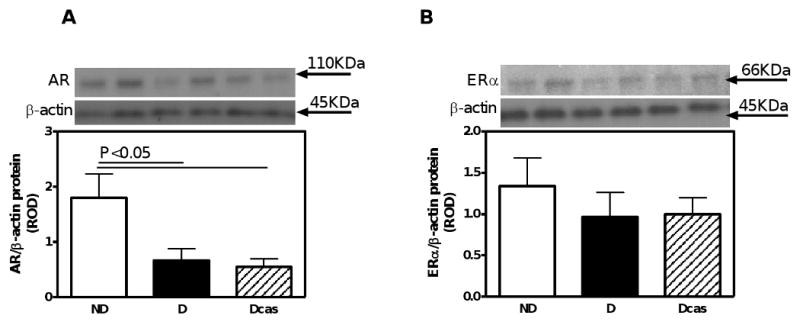

Androgen receptor expression was reduced by 63% in the adrenal gland of D compared with ND rats (Fig. 6A), while castration had no further effect.

Fig. 6.

AR and ERα protein expression in the adrenal gland. A. AR protein expression. B. ERα protein expression. Top panel in A and B, representative immunoblot of AR and ERα, respectively. Bottom panel in A and B, densitometric scans in relative optical density (ROD) expressed as a ratio of AR or ERα/β-actin. Data are expressed as mean±SEM.

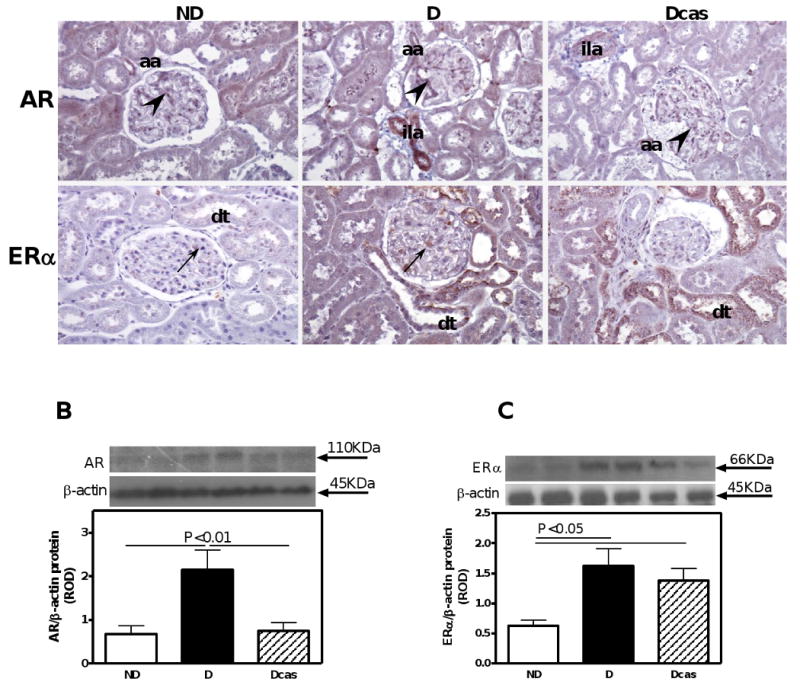

In the kidney, androgen receptors were evident in the afferent arterioles, glomerular endothelial cells and podocytes, as both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 7A). While D increased the intensity of immunostaining as well as protein expression by 215% (Fig. 7B), castration brought the levels of androgen receptor expression to those observed in ND.

Fig. 7.

AR and ERα immunolocalization and protein expression in the kidney. A. AR and ERα immunolocalization. Abbreviations and symbols: distal tubule (dt); afferent arteriole (aa); interlobular artery (ila); podocytes underlined by endothelial cells (arrow heads); mesangial cells (arrows). Original magnification ×400. B. AR protein expression. C. ERα protein expression. Top panel in B and C, representative immunoblot of AR and ERα, respectively. Bottom panel in B and C, densitometric scans in relative optical density (ROD) expressed as a ratio of AR or ERα/β-actin. Data are expressed as mean±SEM.

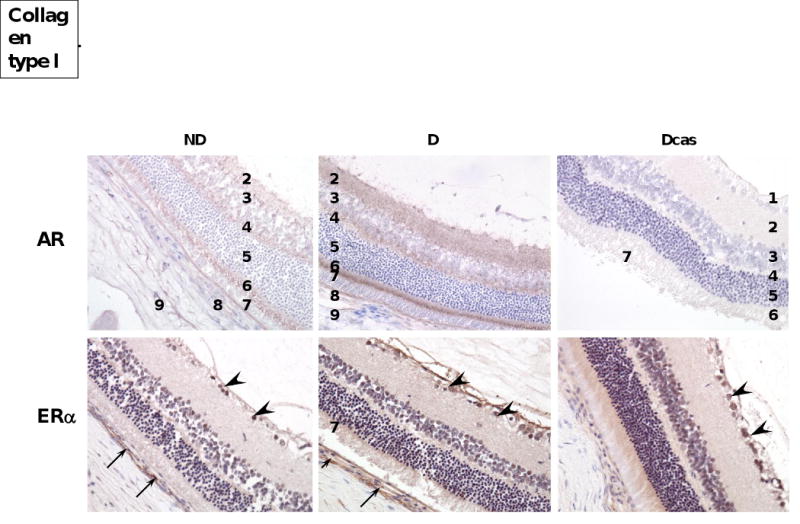

Androgen receptors were widely distributed in the retina: immunolocalization was evident in all but the ganglion and outer nuclear layer (Fig. 8). The intensity of immunostaining appeared to be increased in the D compared with ND, while Dcas showed reduced intensity of immunostaining similar to ND. Unfortunately, we were not able to confirm these findings with Western blotting dye to limited tissue availability.

Fig. 8.

AR and ERα receptor immunolocalization in the eye. AR and ERα immunolocalization. Abbreviations and symbols: 1. ganglion cell layer; 2. inner plexiform layer; 3. inner nuclear layer; 4. outer plexiform layer; 5. outer nuclear layer; 6. rods and cones; 7. pigmented epithelium; 8. choroid; 9. sclera; ganglion cells (arrow heads); capillary (arrows). Original magnification ×400.

3.5. Estrogen receptor expression

In the testis, estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) was exclusively immunolocalized to spermatids (Fig. 5A); however, similar to the AR, no differences in the expression of ERα were observed between the ND and D animals (Fig. 5C). No differences in the expression of ERα were noted also in the adrenal gland (Fig. 6B).

In the kidney, the ERα was immunolocalized to mesangial cells and distal tubules (Fig. 7A) and the intensity of immunostaining was increased in the D compared with ND. ERα protein expression, as measured by Western blotting, was increased by 159% in the D compared with ND animals (Fig. 7C). Castration had no further effect on ERα protein expression.

The pattern of ERα immunolocalization in the retina was similar to that of the AR. Specifically, ERα was immunolocalized to all but the outer nuclear layer (Fig. 8), with the intensity of immunostaining being more prominent in the D compared with ND. No apparent difference in the intensity of immunostaining was observed between D and Dcas. For the same reasons as for ARs, we were unable to quantitate these changes with Western blotting.

4. Discussion

The present study confirms our previous observation of the decrease in circulating testosterone and concomitant increase in estradiol levels in STZ-induced male diabetic rats [7]. We also confirm that castration in STZ-induced diabetic rats does not abolish the diabetes-associated increase in circulating estradiol levels. This lack of an effect of castration, and thus removal of the primary source of testosterone and estradiol, in diabetic animals has also recently been reported by others [4]. These observations suggested that estradiol, at least in diabetic males, may originate from organs other than the testis.

While the mechanisms leading to the decrease in testosterone levels in diabetes have been attributed to hypogonadism [20] associated with reduced gonadotropin secretion [21] and reduced levels of both luteinizing and follicle stimulating hormones [21,22], the mechanisms underlying the increase in estradiol levels even after castration remain unknown. It has been estimated that 30-50% of total androgens in healthy men and up to 75% of estrogens in women is synthesized in peripheral tissues from the inactive precursor dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione (4-DIONE) [8,9]. The percentages of sex hormone production in peripheral tissues increases further with the loss of gonadal steroidogenesis, as occurs during menopause and aging. Under both normal physiological and pathophysiological conditions, as well as aging, DHEA and 4-DIONE are produced in substantial amounts by the adrenal gland and then released into the circulation [23-25]. Indeed, our present study demonstrated high circulating levels of 4-DIONE in non-diabetic rats and these levels remained unchanged in diabetes. Following castration, 4-DIONE levels were lower compared with intact animals, however, the actual presence of 4-DIONE in the circulation after castration supports the idea of it potentially being a source of estrogens after castration. Unfortunately, we did not measure DHEA levels and future studies will need to determine the contribution of DHEA as a potential substrate for steroidogenesis in peripheral organs in diabetes.

Once released from the adrenal gland into the circulation, DHEA and 4-DIONE are taken up by peripheral tissues to be converted into testosterone and estradiol by actions of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases and aromatase [8,9]. Thus, tissues expressing aromatase, the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the conversion of testosterone to estradiol may be able to produce estradiol in the presence of DHEA or 4-DIONE as a substrate. We show that aromatase activity is decreased in the testis of diabetic compared with non-diabetic animals, while no changes in the protein expression were observed. If indeed the testes were the sole source of estradiol in diabetes, then these findings would be more indicative of a reduction, rather than the observed increased levels of circulating estradiol. These observations further support the idea of extra-testicular origins of estradiol in diabetes. We next examined the adrenal gland, however found no differences in either the activity or protein expression in diabetic compared with non-diabetic rats. Furthermore, castration also had no effect on adrenal aromatase activity or protein expression, suggesting that the adrenal gland does not contribute to the excess estradiol production in diabetes in either the presence or absence of the testis. Since our previous study showed that the decrease in circulating testosterone and concomitant increase in estradiol levels in male STZ-induced diabetic rats correlated with the increase in albuminuria and renal pathology associated with diabetes [7], we wanted to examine aromatase activity and expression in the kidney. Our data shows that the diabetic kidney exhibits higher aromatase activity as well protein expression compared with the non-diabetic kidney, suggesting that the diabetic kidneys have the capacity to synthesize estradiol. This increase in aromatase activity and protein expression persisted even after castration, supporting the idea of the sustained production of estradiol in peripheral tissues in the absence the testes. Furthermore, the increase in aromatase activity and expression correlated with increased levels of renal estrogen, demonstrating functional aromatase activity in the kidney. Interestingly, we found aromatase to be immunolocalized predominantly in the areas of renal injury, such as the sclerotic glomerulus and dilated tubules. These observations suggest that estrogen may be produced either in response to injury, as a repair mechanism, or may in fact contribute to glomerulosclerosis and/or tubulointerstitial fibrosis. While previous studies have mainly shown beneficial effects in the diabetic kidney in females [26-29], little is known about the role of estrogens in the kidney in males.

Quite surprisingly, we found very high levels of aromatase activity and expression in the diabetic eye. Others have also shown aromatase localization [14,30] as well as estradiol synthesis in the male retina [31]; however, this is the first report of increased retinal aromatase activity in the diabetic eye, particularly prominent in the choroid capillaries. While the role of estrogens in the pathophysiology of diabetic retinopathy is unclear, a recent study, albeit in diabetic women, has shown that treatment with anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, is associated with a hemi-central retinal artery occlusion [32] and increased prevalence of retinal hemorrhages [33]. These observations would suggest that the presence of estrogens in the diabetic eye is a protective mechanism that may be activated in response to hyperglycemia. Thus, estrogens, at least in women, may have implications for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy, one of the most common complications of diabetes [34]. However, further studies are needed to determine the role and effects of estrogens in the diabetic retina in men.

While the increase in renal and retinal aromatase activity and expression correlate with the increase in circulating estradiol levels seen in diabetes, it is unclear how the kidney and retina-derived estradiol could be released into the circulation. Indeed, the conversion of DHEA and 4-DIONE into testosterone and estradiol is thought to primarily occur in an autocrine and intracrine manner, without significant “spillover” into the circulation [9]. If this indeed is the case, then the increase in circulating estradiol seen in diabetes, even after castration, can not be explained by the increase in renal or retinal estradiol production. What that would argue for is that the locally produced estradiol would exert paracrine or intracrine effects via binding to estrogen receptors on the same cell. Our study shows an increase in ERα protein expression in the kidney and retina (but not in the testes or adrenal gland) in the same target cells expressing aromatase. In addition, androgen receptor expression is also increased in these areas, suggesting that in addition to estrogen, local testosterone production may also exert paracrine/intracrine cellular effects. The question that remains is what is the origin of the excess estradiol in the absence of testes if very little of the renal and retinal estradiol end up in the circulation? Given the fact that it is becoming apparent that many tissues, the brain [10], skeletal muscle [12], prostate gland [9], adipose tissue [13], retina of the eye [14] and the kidney [15,16], have the machinery to produce sex steroids, it is conceivable that even if each tissue releases only a small amount of sex steroids into the circulation, that cumulatively, these amounts become significant. Future studies are needed to more directly examine this idea.

One of the caveats of our study is the method of measuring sex hormone levels, in both the plasma and in homogenized tissues. The commonly used radioimmunoassays and ELISA's for measuring of sex steroids are known to produce values that are highly variable due to a number of factors, such as lack of antibody specificity resulting in cross-reactivity with other steroids and assays sensitivity [35]. Future studies, using high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry methods will need to be performed to verify our findings related to sex hormone levels.

Perspective

Our data suggest that even in the absence of testes, diabetes is associated with elevated levels of estradiol. Tissues, including the kidney and the eye express high levels of aromatase, and thus the capacity to synthesize sex hormones locally in the presence of substrates, DHEA and 4-DIONE released by the adrenal gland. While the physiological significance of estradiol in target tissues needs to be determined, it may be a protective mechanism triggered in response to tissue injury. Since sex steroids can be made locally, circulating hormone levels may not be an accurate parameter reflecting the true exposure to sex steroids in the peripheral target tissues. Thus, local inhibition of sex steroid formation and /or action may have important benefits in the treatment of end-organ damage associated with diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Huimin Zhang and Stephanie Evans for technical assistance with radioimmunoassay and paraffin sectioning, respectively. This work was supported by an RO1 grant (DK075832) from the National Institutes of Health/ National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases to C. Maric.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stellato RK, Feldman HA, Hamdy O, Horton ES, McKinlay JB. Testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, and the development of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged men: prospective results from the Massachusetts male aging study. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:490–494. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasper JS, Liu Y, Pollak MN, Rifai N, Giovannucci E. Hormonal profile of diabetic men and the potential link to prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:703–710. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laaksonen DE, Niskanen L, Punnonen K, Nyyssonen K, Tuomainen TP, Valkonen VP, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin predict the metabolic syndrome and diabetes in middle-aged men. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1036–1041. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun J, Devish K, Langer WJ, Carmines PK, Lane PH. Testosterone treatment promotes tubular damage in experimental diabetes in prepubertal rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1681–F1690. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00482.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roglio I, Bianchi R, Giatti S, Cavaletti G, Caruso D, Scurati S, Crippa D, Garcia-Segura LM, Camozzi F, Lauria G, et al. Testosterone derivatives are neuroprotective agents in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1158–1168. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimizu H, Ohtani KI, Uehara Y, Abe Y, Takahashi H, Tsuchiya T, Sato N, Ibuki Y, Mori M. Orchiectomy and response to testosterone in the development of obesity in young Otsuka-Long-Evans-Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:318–324. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Q, Wells CC, Garman JH, Asico L, Escano CS, Maric C. Imbalance in sex hormone levels exacerbates diabetic renal disease. Hypertension. 2008;51:1218–1224. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.100594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labrie F, Belanger A, Luu-The V, Labrie C, Simard J, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Candas B. DHEA and the intracrine formation of androgens and estrogens in peripheral target tissues: its role during aging. Steroids. 1998;63:322–328. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labrie F. Adrenal androgens and intracrinology. Semin Reprod Med. 2004;22:299–309. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-861547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lephart ED, Lund TD, Horvath TL. Brain androgen and progesterone metabolizing enzymes: biosynthesis, distribution and function. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanderson JT. The steroid hormone biosynthesis pathway as a target for endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Toxicol Sci. 2006;94:3–21. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aizawa K, Iemitsu M, Maeda S, Jesmin S, Otsuki T, Mowa CN, Miyauchi T, Mesaki N. Expression of steroidogenic enzymes and synthesis of sex steroid hormones from DHEA in skeletal muscle of rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E577–E584. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00367.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen PG. Aromatase, adiposity, aging and disease. The hypogonadal-metabolic- atherogenic-disease and aging connection. Med Hypotheses. 2001;56:702–708. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salyer DL, Lund TD, Fleming DE, Lephart ED, Horvath TL. Sexual dimorphism and aromatase in the rat retina. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;126:131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(00)00147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalla Valle L, Toffolo V, Vianello S, Belvedere P, Colombo L. Expression of cytochrome P450scc mRNA and protein in the rat kidney from birth to adulthood. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;88:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinkler M, Diederich S, Bahr V, Oelkers W. The role of progesterone metabolism and androgen synthesis in renal blood pressure regulation. Horm Metab Res. 2004;36:381–386. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.vom Saal FS, Quadagno DM, Even MD, Keisler LW, Keisler DH, Khan S. Paradoxical effects of maternal stress on fetal steroids and postnatal reproductive traits in female mice from different intrauterine positions. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:751–761. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lephart ED, Simpson ER. Assay of aromatase activity. Methods Enzymol. 1991;206:477–483. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)06116-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurments with the Folin-phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukui M, Soh J, Tanaka M, Kitagawa Y, Hasegawa G, Yoshikawa T, Miki T, Nakamura N. Low serum testosterone concentration in middle-aged men with type 2 diabetes. Endocr J. 2007;54:871–877. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k07-077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vermeulen A, Kaufman JM, Deslypere JP, Thomas G. Attenuated luteinizing hormone (LH) pulse amplitude but normal LH pulse frequency, and its relation to plasma androgens in hypogonadism of obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1140–1146. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.5.8496304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strain GW, Zumoff B, Kream J, Strain JJ, Deucher R, Rosenfeld RS, Levin J, Fukushima DK. Mild Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in obese men. Metabolism. 1982;31:871–875. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belanger A, Candas B, Dupont A, Cusan L, Diamond P, Gomez JL, Labrie F. Changes in serum concentrations of conjugated and unconjugated steroids in 40- to 80-year-old men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1086–1090. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.4.7962278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nestler JE, Barlascini CO, Clore JN, Blackard WG. Dehydroepiandrosterone reduces serum low density lipoprotein levels and body fat but does not alter insulin sensitivity in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66:57–61. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stahl F, Schnorr D, Pilz C, Dorner G. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels in patients with prostatic cancer, heart diseases and under surgery stress. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 1992;99:68–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mankhey R, Wells CC, Bhatti F, Maric C. 17-beta estradiol supplementation reduces tubulointerstitial fibrosis by increasing MMP activity in the diabetic kidney. Am J Physiol-Reg, Integr, Comp Physiol. 2006;292:R769–R777. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00375.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixon A, Maric C. 17beta-Estradiol attenuates diabetic kidney disease by regulating extracellular matrix and transforming growth factor-beta protein expression and signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1678–F1690. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00079.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin M, Isono M, Isshiki K, Araki S, Sugimoto T, Guo B, Sato H, Haneda M, Kashiwagi A, Koya D. Estrogen and raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, ameliorate renal damage in db/db mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1629–1636. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62473-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovegrove AS, Sun J, Gould KA, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Lane PH. Estrogen Receptor alpha-mediated Events Promote Sex-Specific Diabetic Glomerular Hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F586–F591. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00414.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guarneri P, Guarneri R, Cascio C, Pavasant P, Piccoli F, Papadopoulos V. Neurosteroidogenesis in rat retinas. J Neurochem. 1994;63:86–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63010086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cascio C, Russo D, Drago G, Galizzi G, Passantino R, Guarneri R, Guarneri P. 17beta-estradiol synthesis in the adult male rat retina. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karagoz B, Ayata A, Bilgi O, Uzun G, Unal M, Kandemir EG, Ozgun A, Turken O. Hemicentral retinal artery occlusion in a breast cancer patient using anastrozole. Onkologie. 2009;32:421–423. doi: 10.1159/000218369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisner A, Falardeau J, Toomey MD, Vetto JT. Retinal hemorrhages in anastrozole users. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:301–308. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31816bea3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kern TS, Barber AJ. Retinal ganglion cells in diabetes. J Physiol. 2008;586:4401–4408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanczyk FZ, Lee JS, Santen RJ. Standardization of steroid hormone assays: why, how, and when? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1713–1719. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]