Abstract

Bloom syndrome is caused by homozygous mutations in BLM, which encodes a RecQ DNA helicase. Patient-derived cells deficient in BLM helicase activity exhibit genetic instability—apparent cytogenetically as sister chromatid exchanges—and activated DNA damage signaling. In this report, we show that BLM-knockout colorectal cancer cells exhibited endogenous, ATM-dependent double-strand DNA break responses similar to those recently observed in Bloom syndrome patient-derived cells. Xenograft tumors established from BLM-deficient cancer cells were not radiosensitive, but exhibited growth impairment that was comparable to that of wild type tumors treated with a single, high dose of ionizing radiation. These results suggest that pharmacological inhibitors of BLM would have a radiomimetic effect, and that transient inhibition of BLM activity might be a viable strategy for anticancer therapy.

Keywords: Bloom syndrome, BLM, ATM, DNA damage, cancer therapy, ionizing radiation, xenografts, gene targeting

Introduction

Bloom syndrome (BS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that causes an extreme predisposition to common cancers. The most obvious cellular characteristic of BS is a high rate of homologous recombination that results in elevated rates of sister chromatid exchanges and losses of heterozygosity.1–3 The clinical and cytological features of BS underscore the causal relationship between genetic instability and tumorigenesis.3

The human BS gene, BLM, encodes a member of the RecQ family of ATP-dependent, 3′–5′ DNA helicases. The primary function of BLM remains to be completely determined, but appears to involve the resolution of DNA structures that arise at stalled DNA replication forks.3 BS cells exhibit defects in replication control, including a reduced DNA replication fork velocity and an elevated frequency of origin firing.4,5 Increased numbers of micronuclei that contain incompletely replicated chromosomes have been found in BS cells.6 At stalled DNA replication forks, BLM localizes to regions of single stranded DNA7 and forms a complex with topoisomerase IIIα that resolves Holliday junction-containing recombination intermediates.2 By functioning to resolve the DNA structures that occur at stalled forks, BLM suppresses homologous recombination. BS cells, deficient in BLM, exhibit replication-associated DNA damage.8

DNA replication intermediates are typically potent activators of ATR, a member of the phosphatidylinositol kinase-like kinase (PIKK) family of serine/threonine kinases.9 ATR can be activated by diverse stimuli that impede the progression of DNA replication forks, including ultraviolet light, DNA crosslinking agents, and inhibitors of nucleotide biosynthesis.10 Along with its downstream substrate Chk1, ATR functions to monitor the progress of DNA replication, stabilizing stalled forks and suppressing the expression of fragile sites.11 BLM deficiency might be expected to cause the accumulation of replication intermediates that trigger an ATR response, but this prediction has not been borne out.12,13

Stalled replication forks can generate double strand DNA breaks (DSBs) and thereby trigger the activation of ATM, another kinase in the PIKK family.14 At DSB sites marked by the phosphorylated form of histone H2AX (known as γH2AX), ATM is rapidly activated and concurrently autophosphorylated on several residues, including S1981.15 Once activated, ATM phosphorylates many downstream targets including the checkpoint kinase Chk2.16,17 Recently, it has been shown that BS cells exhibit expression of γH2AX, phosphorylated ATM and phosphorylated Chk2, and that these DSB signaling proteins colocalize with DNA replication foci.18 Activation of ATM by clinically relevant doses of ionizing radiation (IR) results in the implementation of multiple checkpoints that impede cell cycle progression. The consequences of ATM activation at the low levels observed in BS cells are not known.

Agents that exogenously induce DSBs, including IR and radiomimetic drugs such as doxorubicin, are widely used cancer therapies. To examine the consequences of endogenous DSBs on tumor cell growth, we analyzed the activation of DNA damage signaling pathways in human colorectal cancer cells with targeted BLM alleles.1 Like patient-derived cells, untreated BLM-knockout cancer cells expressed γH2AX and exhibited ATM pathway activation. Chronic activation of DSB responses correlated with a markedly reduced rate of in vivo tumor cell growth, similar to that observed after acute treatment with IR. These results suggest BLM inhibition as a new therapeutic strategy that would mimic some of the effects of radiotherapy.

Results

Cancer cells deficient in BLM activity constitutively phosphorylate Chk2

The recent observation of active DNA damage signaling in BS patient-derived cells prompted us to examine whether cancer cells with experimentally targeted BLM alleles1 would similarly activate PIKK activity. We examined the phosphorylation status of the checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Chk2, which are known to be dependent on the activity of ATR and ATM, respectively.16,19 Replication inhibition triggers the robust phosphorylation of Chk1 on two C-terminal sites, S317 and S345, by ATR.19 As assessed by immunoblot, levels of the S317 and S345 Chk1 phosphoproteins were very low in asynchronous cultures of both the parental cell line HCT116 and the HCT116 BLM−/− derivative (Fig. 1A). In contrast, BLM−/− cells exhibited readily detectable phosphorylation of Chk2 on T68, a residue known to be robustly phosphorylated by ATM in response to DSBs (Fig. 1A). Experimental inactivation of BLM alleles was thus sufficient to detectably activate ATM signaling in the absence of exogenous stimuli. Any activation of ATR that may have occurred in these cells was below the level of detection, and unlikely to be functionally significant. These results demonstrate that targeting BLM alleles in epithelial cells could recreate a cellular phenotype of BS previously observed in fibroblasts.18

Figure 1.

BLM-knockout colorectal cancer cells endogenously activate Chk2. (A) Whole cell lysates made from HCT116 and the BLM-knockout (BLM−/−) derivative cell lines were fractionated, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore) and probed with antibodies against phosphorylated forms of Chk1 (p-Chk1 S317, p-Chk1 S345), total Chk1, phosphorylated Chk2 (p-Chk2 T68) and total Chk2, as indicated. (B) Quantification of p-Chk2 T68 in untreated and IR-treated cells (1 h after treatment) was performed by near-infrared imaging. A single membrane was simultaneously probed with antibodies to p-Chk2 T68 and total Chk2, and developed with green and red IR dyes, respectively (see Materials and Methods). For each band, the signal from p-Chk2 T68 was normalized to the signal from total Chk2 protein. Plotted values are shown in arbitrary units (lower).

In an attempt to measure the low levels of Chk2 activation that were observed in BLM−/− cells, we employed a highly quantitative method of detection that employed near-infrared dyes to simultaneously probe for p-Chk2 T68 phosphoprotein and total Chk2. Both HCT116 and BLM-knockout derivatives robustly activated Chk2 phosphorylation in response to IR (Fig. 1B). Normalized to Chk2 loaded, levels of p-Chk2 T68 were elevated at least 5-fold in BLM−/−, as compared to wild type controls, and were approximately 3 percent of the levels triggered by exposure of the BLM−/− cells to 7.5 Gy IR.

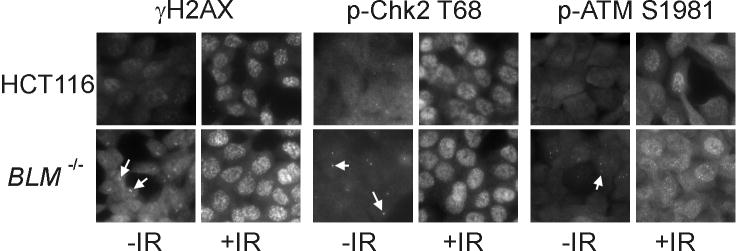

Cancer cells deficient in BLM activity exhibit foci of DSB response proteins

To further quantify the presence of p-Chk2 T68 in asynchronous cultures of BLM−/− cancer cells, we examined DSB response foci by immunofluorescence. Irradiation caused the appearance of numerous distinct nuclear foci of γH2AX, p-Chk2 T68 and p-ATM S1981 in wild type and BLM-knockout HCT116 cells alike. Notably, unirradiated BLM−/− cells also contained foci of all three DSB response proteins (Fig. 2). These foci were of similar intensity as the foci that appeared in irradiated cells, suggesting that they were qualitatively similar, but were far less numerous, with 1–2 foci apparent in approximately 40 percent of the BLM−/− nuclei. DNA strand breaks are known to occur at a low level during normal DNA replication in cells with presumably wild type BLM alleles.20 Nuclear DSB response foci were rare, observed in approximately 2 percent of the untreated, wild type HCT116 cells.

Figure 2.

Elevated numbers of DSB response foci in BLM-knockout cells. γH2AX and phosphorylated forms of ATM (p-ATM S1981) and Chk2 (p-Chk2 T68) were visualized by immunofluorescence in untreated cells (-IR) and in cells 1 h after treatment with 7.5 Gy IR (+IR). Arrows indicate individual foci present in untreated BLM-knockout (BLM−/−) cells.

BLM deficiency impairs the growth of cancer cells in vivo

BLM−/− cancer cells proliferate normally under standard cell culture conditions, with no readily apparent growth defects.1 However, the genetic requirements for growth and survival of human cancer cells in vivo are not uniformly predicted by in vitro cultures.21 To directly examine the effect of BLM deficiency on cancer cell growth in vivo, we used wild type HCT116 and BLM−/− derivatives to establish xenograft tumors in nude mice. BLM−/− tumors took a significantly longer period to grow to a palpable size. While BLM+/+ tumors grew to the desired treatment size range (average of 0.3 cm3) by 8 days after subcutaneous injection, BLM−/− tumors required an average of 27 days of growth to achieve similar size.

Once established, tumors were treated with 7.5 Gy IR. In the weeks following treatment, wild type and BLM−/− tumors grew at a similar rate, indicating that BLM-knockout cells were not radiosensitive. Irradiated wild type HCT116 exhibited a significant suppression of growth as compared with unirradiated controls of the same genotype (Fig. 3). In contrast, the suppressed growth of BLM−/− tumors was only minimally enhanced by radiation treatment. Unirradiated BLM−/− tumors grew only slightly more rapidly than BLM−/− tumors treated with IR (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

BLM-deficiency impairs growth of xenograft tumors. Established tumors derived from wild type HCT116 cells and BLM-knockout (BLM−/−) cells were treated with 7.5 Gy IR and compared with untreated controls. Each treatment and control group contained 5 or 6 tumor-bearing mice; each data point represents the results of two independent experiments.

Discussion

Human somatic cell knockouts have been important tools for the functional assessment of altered genes. In this report, we demonstrate that a BLM-knockout cell line derived from the colorectal cancer cell line HCT116 exhibits endogenous activation of DSB responses similar to that previously observed in BS fibroblasts. HCT116 cells harbor wild type p53 alleles, and it would seem possible that p53 upregulation might contribute to growth suppression in vivo. However, previous studies have failed to establish a significant role for p53 in the response of HCT116-derived xenografts to IR.22 Based on these previous results, we predict that p53 upregulation triggered by BLM deficiency does not account for the severe growth suppression observed in the present study.

When evaluating cellular phenotypes, it is important to consider differences that may be tissue specific. For example, while BLM deficiency causes readily apparent chromosomal instability in cultured fibroblasts, the BLM-knockout epithelial cells used in this study have a stable chromosome complement.1 In contrast, a marked increase in the rate of homologous recombination was observed in patient-derived BS cells,3 in BLM-knockout mouse cells,23 and in BLM-knockout human cells.1 The common occurrence of DNA damage foci in BS fibroblasts and BLM-knockout epithelial cells suggests that endogenous DNA damage, like increased homologous recombination, is a central feature of BS and may contribute to tumorigenesis.

While the cellular roles of the BLM helicase remain under intense investigation, it has become clear that BLM deficiency has a substantial impact on the process of DNA replication.8 Given the evidence of abnormal DNA replication in BS patient-derived cells, including decreased fork velocity, increased origin density, and increased incidence of measurable DNA replication intermediates,18 one might predict concomitant activation of ATR pathways that respond to slowed replication. The absence of detectable ATR activation in BS cells18 and in BLM-knockout cancer cells (Fig. 1), while perhaps surprising, suggests that the effect of BLM-deficiency at the level of the DNA replication fork is qualitatively different from that caused by exogenous agents, such as ultraviolet light or hydroxyurea, which trigger rapid and robust ATR responses.10 The frequent appearance of foci containing phosphorylated H2AX, ATM and Chk2 in BLM−/− cells and the absence of Chk1 phosphorylation strongly suggests that the primary DNA lesion caused by loss of BLM function is the DSB.

Analysis of relative levels of Chk2 phosphoprotein (Fig. 1B) and numbers of DSB foci (Fig. 2) in untreated BLM-knockout cells suggested a density of DSBs that was approximately 2–3 percent of that observed after a single acute IR dose of 7.5 Gy. Assuming a linear relationship between IR dose, Chk2 phosphoprotein levels and numbers of DSB foci, the steady state level at which BLM-deficiency causes DSBs in these cells is estimated to be roughly equivalent to an acute IR dose of 200 cGy. Calculation of the total IR dose-equivalent over time would require an estimate of the half life of DSB foci in BLM-deficient cells, which is not currently known.

DNA damage signaling potently suppresses cell growth.9 Our xenograft study suggests that the relatively low level of endogenous ATM activation observed in BLM-deficient cells can, over time, cause a dramatic suppression of growth in vivo. We found the degree of tumor growth suppression to be similar to that caused by a single 7.5 Gy dose of IR (Fig. 3). As has been previously shown in BLM−/− cells derived from knockout mice,24 targeting BLM in human cancer cells did not cause radiosensitivity. Indeed, exogenous DNA damage had a relatively minimal affect on the growth of BLM−/− tumors; irradiated BLM−/− tumors were only modestly suppressed compared to untreated controls. Rather, these results demonstrate that BLM deficiency may be radiomimetic. The level of ATM pathway activation in untreated BLM-knockout cells was comparatively low (Figs. 1 and 2), but nonetheless sufficient to cause near-maximal growth suppression under these conditions. Notably, in vitro growth of BLM-knockout cells was very similar to wild type HCT116 (data not shown). These observations underscore the high degree of sensitivity with which xenograft systems can reveal the effects of diverse growth inhibitors.

The generalized observation of activated ATM signaling pathways in BLM-knockout cells and the associated growth suppression that we observed in vivo suggests that BLM might be an attractive target for novel forms of cancer therapy. Several compounds that bind the minor groove of the DNA helix have been found to be potent BLM inhibitors.26 While lifetime deficiency of BLM activity is certainly detrimental, as evidenced by the severe cancer predisposition and other symptoms experienced by BS patients, short term inhibition of BLM might be relatively well tolerated. Radiotherapy is useful in the treatment of the majority of tumor types. Because the cellular responses to IR and BLM deficiency appear to be very similar, if perhaps not identical, we predict that chemical inhibitors of BLM helicase activity might have broad antitumor applications.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HCT116 cells and BLM-knockout derivatives of HCT116,1 were cultured as subconfluent monolayers in McCoy’s 5A medium, supplemented with 10 percent fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 1 percent Penicillin/Streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Immunoblots

Cells were directly lysed in 1X NuPAGE sample buffer (Invitrogen). Lysates were analyzed with antibodies directed against total Chk1 or Chk2 (Santa Cruz) or p-Chk1 S317, p-Chk1 S345, p-Chk2 T68 (Cell Signaling), as described.25 High sensitivity blots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Biosciences). Quantitative multiplex blots were developed by near infrared imaging, using IRDye 800CW (green) for detection of phosphoprotein and IRDye 700CW (red) for detection of total Chk2. Blots were scanned on the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LiCor) and bands were individually quantified using Odyssey 2.0 software.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded on Poly-D-lysine coated chamber slides (Nunc). Following IR treatment, cells and untreated controls were sequentially fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Alrich) at room temperature. Diluted primary antibodies directed against γH2AX (Upstate Biotechnology), p-ATM S1981 and p-Chk2 T68 (Cell Signaling Technologies) were incubated with cells overnight. Following incubation with a biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), bound antibody complexes were visualized by staining with avidin-AF488 (Molecular Probes). Images were captured on a Nikon E800 fluorescence microscope with a 60X Oil immersion Plan Apo objective (1.4 aperture) and a 5MHz interline CCD camera (Princeton Instruments), using Metamorph imaging software (version 6.0).

Treatment with ionizing radiation

Cells were irradiated with a 137Cs GammaCell 40 irradiator (Atomic Energy of Canada), at a dose rate of 0.7 Gy/min. Xenograft tumors were treated at a dose rate of 8.1 Gy/min in a Shepard 137Cs irradiator, with the body of the subject animal protected by lead shielding.

Xenograft growth and treatment

Xenografts were generated as described.22 HCT116 cells and BLM-knockout derivatives growing in tissue culture flasks were detached with trypsin and counted by flow cytometry (BD-Coulter). A total of 5 x 106 cells of either genotype were suspended in 0.7 ml PBS and subcutaneously into the flanks of 4–6 week old athymic nude mice (NCI). Xenograft tumors were 0.20–0.45 cm3 at the time of treatment. Orthogonal tumor measurements were taken twice weekly. Tumor volume was calculated as volume = length x width x height x 0.52.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance of the staff of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center Cell Imaging Core facility. Grant support for this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health (CA104253) and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute.

Abbreviations

- BS

Bloom syndrome

- BLM

Bloom syndrome helicase

- PIKK

phosphatidylinositol kinase-like kinase

- DSB

double strand DNA break

- IR

ionizing radiation

References

- 1.Traverso G, Bettegowda C, Kraus J, Speicher MR, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. Hyper-recombination and genetic instability in BLM-deficient epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8578–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu L, Hickson ID. The bloom’s syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003;426:870–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickson ID. RecQ helicases: Caretakers of the genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:169–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hand R, German J. A retarded rate of DNA chain growth in bloom’s syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:758–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.2.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ockey CH, Saffhill R. Delayed DNA maturation, a possible cause of the elevated sister-chromatid exchange in bloom’s syndrome. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:53–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yankiwski V, Marciniak RA, Guarente L, Neff NF. Nuclear structure in normal and bloom syndrome cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5214–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090525897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brosh RM, Jr, Li JL, Kenny MK, Karow JK, Cooper MP, Kureekattil RP, Hickson ID, Bohr VA. Replication protein A physically interacts with the bloom’s syndrome protein and stimulates its helicase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23500–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rassool FV, North PS, Mufti GJ, Hickson ID. Constitutive DNA damage is linked to DNA replication abnormalities in bloom’s syndrome cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:8749–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2177–296. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osborn AJ, Elledge SJ, Zou L. Checking on the fork: The DNA-replication stress-response pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:509–16. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casper AM, Nghiem P, Arlt MF, Glover TW. ATR regulates fragile site stability. Cell. 2002;111:779–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies SL, North PS, Dart A, Lakin ND, Hickson ID. Phosphorylation of the bloom’s syndrome helicase and its role in recovery from S-phase arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1279–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1279-1291.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho CC, Siu WY, Lau A, Chan WM, Arooz T, Poon RY. Stalled replication induces p53 accumulation through distinct mechanisms from DNA damage checkpoint pathways. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2233–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GC, Lukas J, Jackson SP. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1998;282:1893–187. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, Shiloh Y, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao VA, Conti C, Guirouilh-Barbat J, Nakamura A, Miao ZH, Davies SL, Sacca B, Hickson ID, Bensimon A, Pommier Y. Endogenous gamma-H2AX-ATM-Chk2 checkpoint activation in bloom’s syndrome helicase deficient cells is related to DNA replication arrested forks. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:713–24. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, Piwnica-Worms H. ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4129–439. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4129-4139.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saleh-Gohari N, Bryant HE, Schultz N, Parker KM, Cassel TN, Helleday T. Spontaneous homologous recombination is induced by collapsed replication forks that are caused by endogenous DNA single-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7158–69. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7158-7169.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamb JR, Friend SH. Which guesstimate is the best guesstimate? predicting chemotherapeutic outcomes. Nat Med. 1997;3:962–3. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bunz F, Hwang PM, Torrance C, Waldman T, Zhang Y, Dillehay L, Williams J, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:263–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chester N, Kuo F, Kozak C, O’Hara CD, Leder P. Stage-specific apoptosis, developmental delay, and embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a targeted disruption in the murine bloom’s syndrome gene. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3382–393. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo G, Santoro IM, McDaniel LD, Nishijima I, Mills M, Youssoufian H, Vogel H, Schultz RA, Bradley A. Cancer predisposition caused by elevated mitotic recombination in bloom mice. Nat Genet. 2000;26:424–49. doi: 10.1038/82548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurley PJ, Wilsker D, Bunz F. Human cancer cells require ATR for cell cycle progression following exposure to ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2007;26:2535–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brosh RM, Karow JK, White EJ, Shaw ND, Hickson ID, Bohr VA. Potent inhibition of Werner and Bloom helicases by DNA minor groove binding drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2420–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]