Abstract

Bone repair and regeneration is one of the most extensively studied areas in the field of tissue engineering. All of the current tissue engineering approaches to create bone focus on intramembranous ossification, ignoring the other mechanism of bone formation, endochondral ossification. We propose to create a transient cartilage template in vitro, which could serve as an intermediate for bone formation by the endochondral mechanism once implanted in vivo. The goals of the study are 1) to prepare and characterize type I collagen sponges as a scaffold for the cartilage template, and 2) to establish a method of culturing chondrocytes in type I collagen sponges and induce cell maturation. Collagen sponges were generated from a 1% solution of type I collagen using a freeze/dry technique followed by UV light crosslinking. Chondrocytes isolated from two locations in chick embryo sterna were cultured in these sponges and treated with retinoic acid to induce chondrocyte maturation and extracellular matrix deposition. Material strength testing as well as microscopic and biochemical analyses were conducted to evaluate the properties of sponges and cell behavior during the culture period. We found that our collagen sponges presented improved stiffness and supported chondrocyte attachment and proliferation. Cells underwent maturation, depositing an abundant extracellular matrix throughout the scaffold, expressing high levels of type X collagen, type I collagen and alkaline phosphatase. These results demonstrate that we have created a transient cartilage template with potential to direct endochondral bone formation after implantation.

Keywords: chondrocytes, type I collagen, type X collagen, alkaline phosphatase, tissue engineering, endochondral ossification

Introduction

Bone and cartilage regeneration are two important areas of intense research effort world wide.1 Primarily, those studies focus on regenerative approaches for bone and cartilage defects2–5 and secondarily they try to understand the molecular mechanisms responsible for degenerative processes of the skeletal system such as osteoarthritis.6,7

Cartilage regeneration approaches initially attempted to use the patients own chondrocytes.1,8 These chondrocytes were harvest, allowed to proliferate in vitro and finally implanted into the defects. This strategy not only involved two surgeries, but allowed only a small number of cells to be harvested, requiring in vitro expansion/proliferation for long periods of time before implantation.2 To overcome these difficulties, many studies using stem cells have been conducted over the last years.1,9–11 The bone regeneration field faces similar difficulties, having explored the use of osteoblasts like cells, stem cells and growth factors or their combination, to create osteoinductible scaffolds.12–14

Both bone or cartilage regeneration approaches require a biocompatible material as a scaffold to support cells proliferation as well as to withstand mechanical solicitations. Ceramic materials were for several years the main scaffolds used in bone regeneration. However their low biodegradability, high hardness and high modulus lead researchers to study other alternatives such as polymers.3 Natural polymers, such as chitosan, alginate and collagen present great solutions and their use has been growing exponentially.15–17 Since bone is mainly a combination of organic and inorganic compounds, studies attempted to recreate its structure by using scaffolds prepared from a combination of polymers and ceramics.17,18

Among natural polymers, collagen is the most abundant protein in mammals. It provides structural and mechanical support to tissues and organs,19 and fulfill biomechanical functions in bone, cartilage, skin, tendon, and ligament. Collagen scaffolds have been used in numerous medical applications: drug delivery, hemostatic pads, skin substitutes, soft tissue augmentation, suturing and as tissue engineering substrate.20–23 Collagen scaffolds are processed in a variety of forms.24 Thin sheets and gels are substrates for smooth muscle,25–27 renal28 hepatic,29 endothelial27 and epithelial cells,30 while sponges are often used to engineer skeletal tissues such as cartilage,31,32 tendon33,34 and bone.35,36 Collagen is biodegradable and has low or negligible antigenicity.37,38

Forms of collagen type I, commonly extracted from bovine tendon, are biocompatible and adequate scaffolds for tissue engineering in terms of mechanical properties, pore structure, permeability, hydrophilicity and in vivo stability.39 Several immunological studies (animal models) of injectable collagen gels and implanted collagen sponges, confirm little or no antibodies to collagen type I are detected.40,41 Collagen type I has been shown to support osteoblast, osteoclast, and chondrocyte attachment, proliferation, and differentiation in vitro as well as in vivo.31,35,36,42,43

To the best of our knowledge, collagen scaffolds were never used as support for chondrocytes maturation to obtain a transient cartilage structure for endochondral bone formation. As opposed to intramembranous ossification, where bone is formed by differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteoblasts, endochondral ossification requires an intermediate stage, where a transient cartilage model of the future bone is gradually converted into the final bone structure. This pathway is responsible for formation of most of the bones in our bodies.

Exploring the endochondral pathway for bone formation presents significant advantages such as of the high rate of chondrocyte proliferation, these cells resistance to low oxygen44,45 and the ability of chondrocyte to induce angiogenesis and osteogenesis.46,47 In our previous studies we used a chitosan scaffolds and calcium phosphate materials48,49 to prepare transient cartilage templates for bone formation. Indeed, endochondral ossification was induced as early as one month after scaffold implantation in vivo.50

While collagen presents better biocompatibility and biodegradability than other polymers, in terms of mechanical properties, polymers such as chitosan provide stronger and stiffer scaffolds48 even after crosslinking of collagen.51 In this project we decided to use collagen type I as a scaffold for a transient cartilage template for bone regeneration because of its ability to support both chondrocytes and osteoblasts proliferation and differentiation. We reasoned that since transient cartilage templates mineralize the extracellular matrix, our approach will combine collagen excellent biocompatibility with improved osteoinductive and mechanical properties, provided by chondrocyte’s signals and the abundant mineralized extracellular matrix.

Materials and methods

2% bovine collagen gel, prepared as described in Yost et al.52 was diluted to a 1% solution with 0.012N HCl, centrifuged to remove air, transferred to a 24 well plate again centrifuged for an even surface, kept overnight −80 °C, and freeze dried (Virtis Freezemobile-12EL, Gardiner, NY) to obtain a porous structure. These sponges were crosslinked under UV light (120 μW/cm2), and neutralized with distilled water four times (30 min each) then Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Cellgro, Mediatech Inc, Fairlawn, NJ) twice (20 min each).

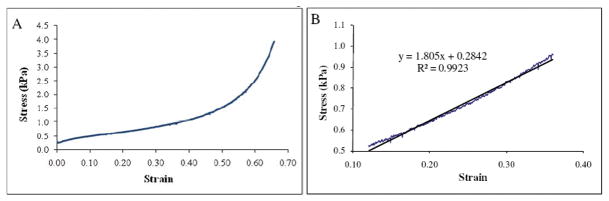

Uniaxial load at a constant strain rate of 0.1 mm/s was applied with a 30 mm diameter cylindrical probe on six fully hydrated sponges (diameter 15.0±0.5 mm, thickness 2.9±0.2 mm), (Texture Analyser (TA-XT2i, Stable Micro Systems Ltd, Surrey, UK). Force and displacement and “stress vs. strain” curves plotted. Both compression strength and elastic modulus were determined on linear area of curves (Figure 1) for 30% of deformation, as per Mow et al.53 Compression strength was obtained directly from curves “stress vs. strain” (Figure 1A) while elastic modulus was computed using the linear equation of trend-lines at 30% of deformation (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Stress vs. strain curves of hydrated collagen type I sponges.

Sponges deformation was evaluated in compression tests. Stress and strain was calculated from the recorded values of force and displacement. Image A shows whole compression curve while image B shows the linear equation and the trend-line of a restrict area close to 30% of deformation.

Chondrocytes were isolated from two locations in the sternum of 14 day chick embryos using method of Iwamoto et al.54 The cephalic (CP) sternal chondrocytes (upper region of sternum) behave like transient cartilage cells and can undergo hypertrophy and induce bone formation, while caudal (CD) sternal chondrocytes (lower region of sternum) behave as permanent cartilage cells, do not undergo hypertrophy, and therefore were used as control.48 Freshly isolated chondrocytes were plated in 100mm tissue culture dishes for 7 days in 10 ml complete medium [DMEM containing 10% Nu serum (Fisher scientific, Fairlawn, NJ), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma, St Louis, MO)]. After one week, 200,000 chondrocytes in 10 μl media were seeded on each collagen type I sponge in a 96 well plate, and incubated 2 hours, before adding 200 μl of complete medium, carefully not to disturb the sponge and cells. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2 atmosphere. Media changed every day for 5 days before treatment with 100 nM all trans-retinoic acid and 50 μg/ml of ascorbic acid (every day for another 5 days), to induce chondrocyte maturation/hypertrophy and matrix synthesis. These specimens were then used for testing and imaging.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) collagen scaffolds, alone or with chondrocytes, were washed with phosphate buffered saline, fixed (2% gluteraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cocodylate HCl buffer with 0.1 M sucrose, pH 7.2) overnight at 4 °C, dehydrated in ethanol series at room temperature, and critical point dried (Denton Vaccum, Cherry hill, NJ). Samples were mounted, sputter coated with gold palladium (Emitech K-650), and viewed on SEM (Hitachi S-3500 N, Schaumburg, IL) using secondary electron emission at 10 kv.

For immunohistochemistry, samples were embedded in paraffin and 5 μm sections cut. After deparaffinization and rehydration, immunostaining was performed using a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and antibodies against chick alkaline phosphatase and collagen type X. Sections were counterstained with Alcian blue (1% alcian blue in 3% acetic acid), and light green, mounted, and scanned on Scan Scope GL optical microscope (Aperio, Bristol, UK) at 10X.

Cell supernatant for DNA and protein content, and alkaline phosphatase activity was extracted from 4 sets of 2 sponges with CP and CD chondrocytes by collection in 150 μl 0.1% Triton-X (Fisher Scientific, Fairlawn, NJ), homogenized in eppendorf tubes (on ice, 1 hour), and scaffolds crushed to extract cells and proteins. Cell extract centrifuged at 3000 rpm, 2 minutes.

DNA measurements were performed as in Teixeira et al.55 using a bisBenzididazole dye (Hoechst 33258 dye, Polyscience Inc., Northampton, UK). Fluorescence was measured by spectrofluorometer (Beckman Coulter DU-640) at wavelengths of 365 and 460 nm. A standard curve using calf thymus DNA (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and regression analysis was used to calculate DNA amount.

Protein measurements were performed using DC Protein Assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). A spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter DU-640, Fullerton, CA) was used to measure at an absorbance of 750 nm. A standard curve of bovine serum albumin and regression analysis were used to calculate protein content in the samples.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity was measured as in Leboy et al.56 Quantification of AP activity used a colorimetric assay in which p-Nitrophenyl phosphate is hydrolyzed into p-Nitrophenol and inorganic phosphate, forming a yellow complex measured at 400–420 nm. AP activity was expressed as nmol of product/minute/μg protein; 1 absorbance unit change=64 nmol product.

RNA was isolated from scaffolds at day 5 and 10 (5 days of RA treatment) for PCR. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol® reagent (Life Technologies, Gaitherburg, MD) per manufacturer’s instructions with modifications. Briefly, samples were liquid nitrogen frozen and crushed, Trizol® reagent added, vortexed 30 sec, then kept at 4 °C for 2 hours. 0.2 volume chloroform added for 15 min, then solution centrifuged at 12,000 g, 30 min, at 4 °C for phase separation. The aqueous phase containing the RNA was collected, mixed with high salt precipitation solution (0.8 M sodium citrate and 1.2 M NaCl and isopropanol) and centrifuged at maximum speed for 30 min at 4 °C. RNA was purified using RNA micro kit (Qiagen Inc, Chatsworth, CA) according to RNeasy cleanup protocol. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen Inc.), a DNA Engine Optican2 system (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA), and primers specific for chick genes: type X collagen (forward: AGTGCTGTCATTGATCTCATTGGA, reverse: TCAGAGGAATAGAGACCATTGGATT), alkaline phosphatase (forward: CCTGACATCGAGGTGATCCT, reverse: GAGACCCAGCAGGAAGTCCA), type I collagen (forward: GCCGTGACCTCAGACTTAGC, reverse: TTTTGTCCTTGGGGTTCTTG). Acidic ribosomal protein (RP) mRNA was used as a reference for quantification (forward: AACATGTTGAACATCTCCCC, reverse: ATCTGCAGACAGACGCTGGC). Primers were purchased from Qiagen Inc (Valencia, CA). Results were presented as “fold change” in gene expression and calculated using the threshold cycle (Ct) and the formula below, where “CD” refers to CD chondrocytes, “CP” refers to CP chondrocytes, and “RP” refers to the acidic ribosomal protein: x=2ΔΔCt, in which ΔΔCt=ΔE − ΔC, and ΔE = CtCP − CtRP, and ΔC = CtCD − CtRP. A ΔΔCt < 0 was considered a decrease while a ΔΔCt > 0 was considered an increase in gene expression.

For statistical analysis, all experiments were repeated 3–4 times and the mean and standard deviation were determined. Significant differences between test groups and controls were assessed by ANOVA. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

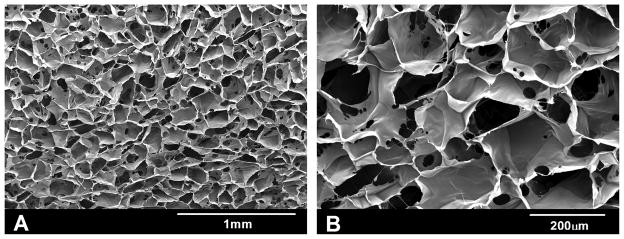

Scanning electron microscopy was performed in different cross sections to evaluate the porosity. There is a homogeneous distribution of pores throughout the sponges (Figure 2). The average pore size is 150±25 μm. Compression tests (Figure 1) showed that strength of sponges reached 0.79±0.04 kPa and the elastic modulus was 1.80±0.13 kPa.

Figure 2. Scanning electron microscopy of collagen type I sponges.

Photomicrographs of cross sections of collagen sponges are shown. Image A (50X) shows homogenous size and distribution of pores and image B (150X) shows the good interconnectivity between the pores.

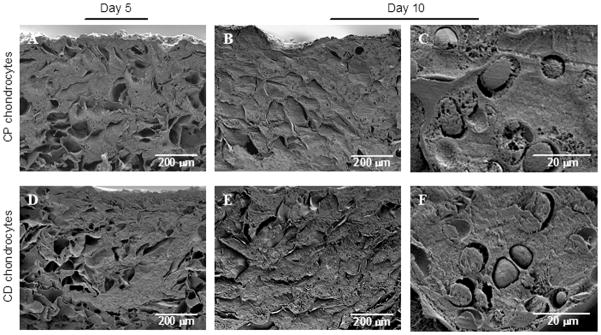

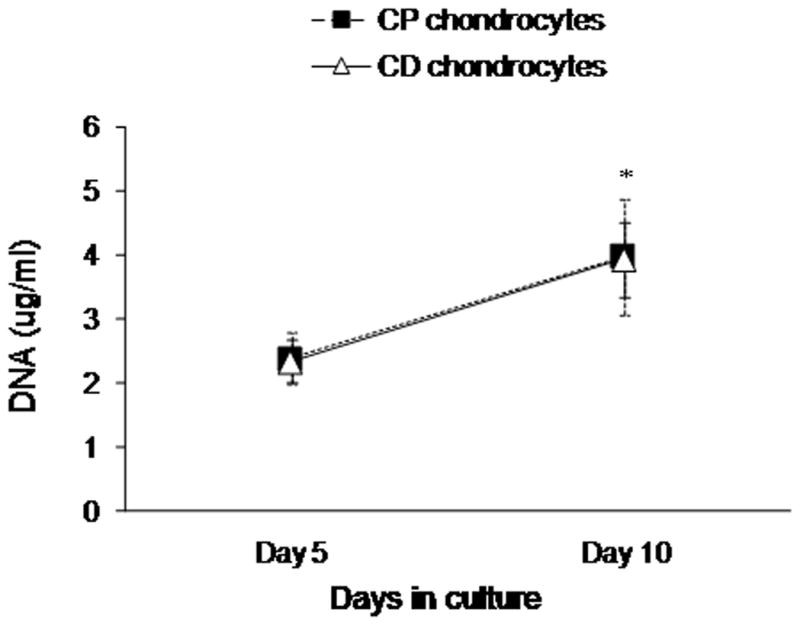

Scanning electron microscopy analyses of collagen sponges cultured with either CP or CD sternal chondrocytes (Figure 3) reveal that cells attached and proliferated deep into the scaffold, filling most of the pores with extracellular matrix after only 5 days in culture. At the end of 10 days in culture (day 5 of maturation treatment), the pores were completely packed with cells encased in a compact extracellular matrix. No difference in matrix amount for CP or CD chondrocytes was seen. Measurement of DNA content in sponges cultured for 5 and 10 days, confirmed extensive cell proliferation in the scaffolds (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscopy of collagen sponges cultured with chondrocytes.

CP and CD chondrocytes were grown on collagen sponges for 5 days and then treated with retinoic acid for the next 5 days to induce maturation. CP chondrocyte cultures, A (day 5), B and C (day 10). CD chondrocyte cultures, D (day 5), E and F (day 10)

Figure 4. Rapid proliferation of chondrocytes on collagen sponges.

CP and CD chondrocytes were grown on collagen sponge for 5 days and then treated with retinoic acid for the next 5 days to induce chondrocyte maturation. DNA was measured after 5 and 10 days in culture. *Significant difference from day 5 for both CP and CD chondrocytes.

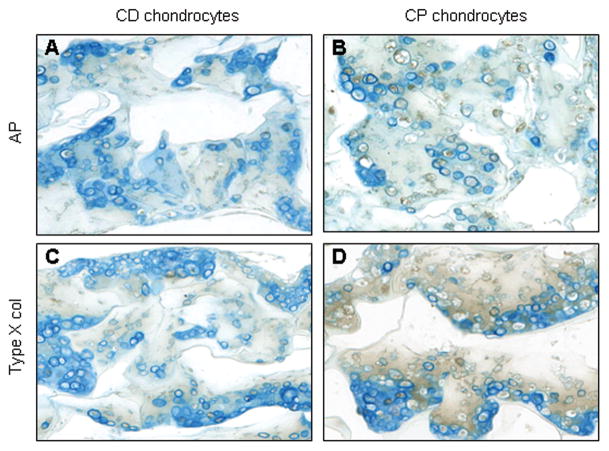

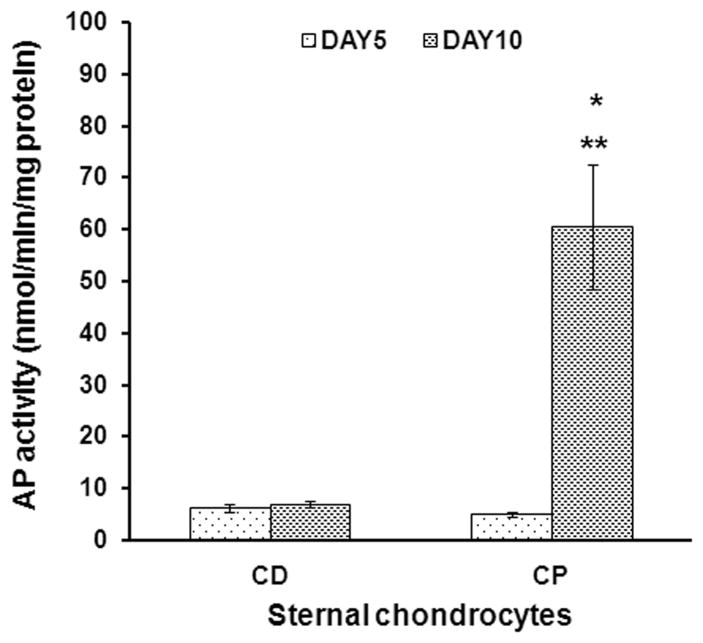

To evaluate chondrocyte maturation in response to ascorbic and retinoic acid, we performed immunohistochemical staining for alkaline phosphatase and collagen type X, important markers of hypertrophic phenotype.57,58 The CP chondrocytes produced higher levels of AP (Figure 5B) and collagen type X (Figure 5D), visualized by dark brown staining. Furthermore, measured AP activity increased significantly in CP chondrocytes in response to retinoic acid and ascorbic acid treatment (Figure 6). In contrast, CD chondrocytes did not respond to maturation agents, and AP enzymatic activity remained low. The 10 fold difference in AP activity between CP and CD chondrocytes at day 10 (6.9±1 nmol/min/mg versus 60±12 nmol/min/mg) highlights these different chondrocyte phenotypes.

Figure 5. Immunohistochemical staining collagen sponges cultured with chondrocytes.

Histological cross sections of sponges collected after 10 days in culture were immunostained with antibodies against alkaline phosphatase (A, B), and type X collagen (C,D). A and C are cross sectional views of the sponges with CD chondrocytes, while B and D are sponges with CP chondrocytes. AP and type X collagen are evidenced by the presence of brown color.

Figure 6. Retinoic acid treatment increases AP activity in CP chondrocytes.

CP and CD chondrocytes were grown on collagen sponges for 5 days and then treated with retinoic acid for the next 5 days to induce chondrocyte maturation. Graph shows AP activity levels, measured spectrophotometrically, and normalized for total protein content in the samples. *Significant difference from CP chondrocytes at day 5. **Significant difference from CD chondrocytes day10.

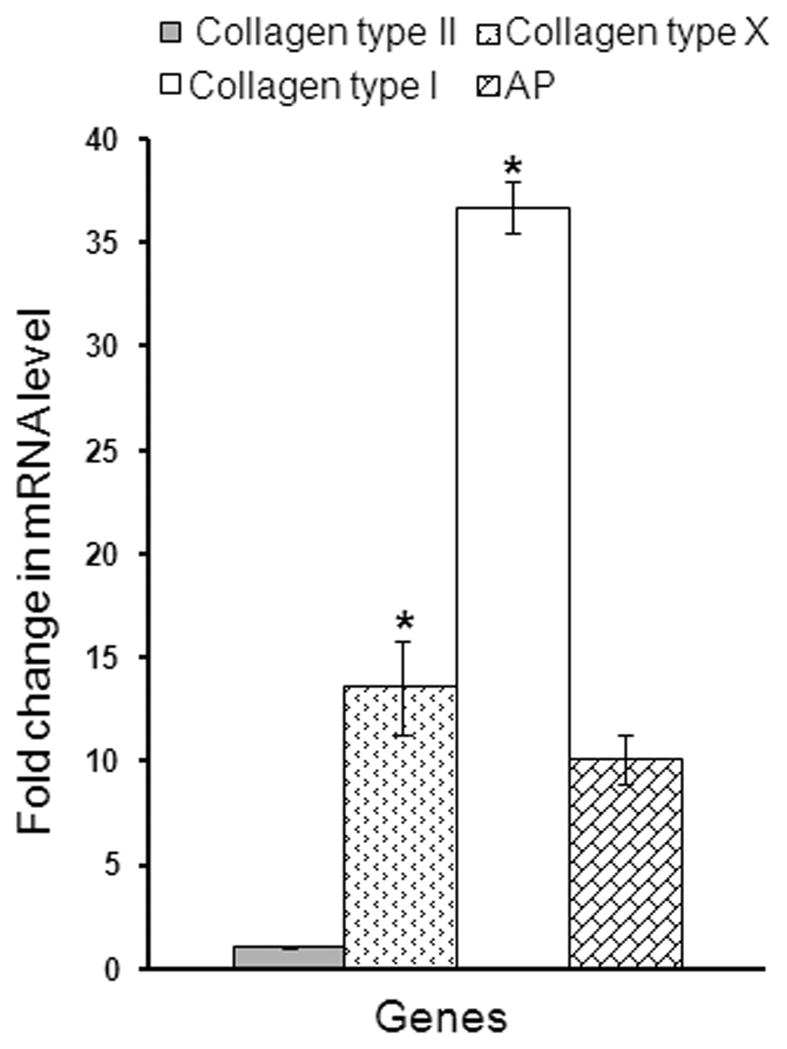

To further investigate the differences in phenotype, we studied the gene expression profile at the end of the culture period by RT-PCR. A value higher than 1, corresponds to a higher gene expression level in CP chondrocytes when compared to CD cells. Except for collagen type II (no change) all genes studied were expressed at higher levels in CP chondrocytes than in CD chondrocytes. As seen in figure 7, collagen type X (early hypertrophy marker), and collagen type I (late hypertrophy marker) expression was significantly higher in CP cells. While AP gene expression was higher for CP chondrocytes, it was not statistically significant.

Figure 7. Gene expression profile of upper sternal chondrocytes when compared to lower sternal chondrocytes.

CP and CD chondrocytes were grown to confluence for 5 days and then treated with retinoic acid for additional 5 days. mRNA was extracted at the end of the culture period (10 days) from CP and CD chondrocytes. RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for chick genes. Expression levels are presented as “fold change” in mRNA levels in CP chondrocytes in relation to CD chondrocytes. *Significantly different from CD chondrocytes.

Discussion

The collagen sponges we developed are approximately 20 times stiffer than those reported in the literature (≈0.1 kPa), comparable only to collagen sponges incorporating 40% of poly(glycolic acid) fibers (≈2.5 kPa).51 While we did not measure pore connectivity, our results show that proliferating chondrocytes reached the interior of the scaffold and initiated extensive intracellular matrix deposition in only 5 days. Our sponges maintained their shape/stability, while providing adequate porosity for cells to fully migrate, and supporting cell phenotype and correct differentiation. Therefore, these scaffolds successfully meet the major challenges in tissue engineering, unlike previous studies. Takahiro et al.32 cultured articular chondrocytes in bovine collagen type I sponges for 4 weeks, resulting in uncompleted cell penetration into the scaffold (as seen in histological sections) and loss of the cartilage phenotype (decreased collagen type II expression). A study by Chen et al.59 using a polymer/collagen type I hybrid sponge to culture bovine articular chondrocytes, showed that while supporting chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation in vitro, the sponges collapsed and lost shape, in vivo.

But collagen type I has mostly been used as a scaffold for bone formation with bone marrow stromal cells or differentiated osteoblasts. Mizuno et al.42 cultured bone marrow stromal cells on different collagen gels for 20 days before subcutaneous implantation in nude mice for 4 weeks. These cells differentiated into osteoblasts only in collagen type I gel, suggesting that it alone offers a suitable environment for the induction of osteoblastic phenotype in vitro and osteogenesis in vivo.38 In a study by Domaschke et al.35 osteoblasts and osteoclasts were co-cultured on a mineralized collagen type I membrane. Both cell types attached and proliferated, maintained phenotype (evaluated by RT-PCR), and completely covered the membrane within 2 weeks. Rodrigues et al.36 using human osteoblasts cultured in mineralized collagen type I gel showed similar results. These studies used collagen membrane or gel that had to be mineralized for improved mechanical properties. Collagen sponges can provide a better porous structure and 3-D platform for bone deposition and blood vessel ingrowth. Indeed, our sponges proved stronger than others, and did not need mineralization for improved stability.

All these previous studies support the use of collagen type I as a scaffold to create a transient cartilage template, sustaining both chondrocyte and osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. Our results confirm that chondrocytes attach, proliferate and mature on a collagen type I scaffold, maintaining their characteristic ovoid shape in the matrix lacunae. We induced chondrocyte hypertrophy by treatment with retinoic and ascorbic acid, which resulted in an increase in mRNA levels of hypertrophy markers (AP and collagen type X). We also observed an increased in the expression of type I collagen by hypertrophic cells. The expression of genes characteristic of the osteoblast phenotype by growth plate chondrocytes has previously been reported,60 typically including the expression of high levels of alkaline phosphatase, collagen type I, and several non collagenous matrix proteins enriched in bone (osteonectin, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein and osteocalcin).60–66 Both in vivo and in vitro studies provide evidence that the hypertrophic chondrocyte may undergo further differentiation and express bone cell markers,61,63 suggesting a role for chondrocytes at the initial stages of endochondral bone deposition.

Previous bone engineering approaches focused on bone formation via intramembranous ossification (when using bone marrow stromal cells) or direct osteoblast activity, and most cartilage engineering approaches aim to regenerate permanent cartilage,31,32,59,67 however our objective is to create a transient cartilage as an improved osteoinductive template for endochondral ossification. Our study used hypertrophic chondrocytes that are well adapted to low oxygen tension, resisting hypoxic conditions like the ones most likely created by a large mass of cells.44,45 In addition, chondrocytes can induce osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells.68 Hypertrophic chondrocytes also secrete VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), that has been shown to induce vascularization, osteoblast migration and differentiation, and osteoclast survival and resorption activity.46,47 All these mechanisms are required during the process of endochondral bone formation. Therefore, we believe that our approach to bone tissue engineering, takes advantage of this effective chondrocyte signaling mechanism to develop an osteoinductive scaffold. Our work using chitosan scaffolds shows that hypertrophic chondrocytes efficienly induce extensive bone formation once implanted in vivo.50

In conclusion, while current research aims at clarifying some of the factors and signaling pathways controlling bone formation, approaches such as ours that provide a reservoir of differentiation factors in the form of a transient cartilage template have great potential for bone regeneration and tissue engineering.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Association of Orthodontics Foundation, the NIDCR grant 5K08DE017426, the Luso-American Foundation (Portugal), the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (Portugal) and by the PRODEP (Portugal). The authors thank Ms. Gloria Turner, Department of Pathology at New York University College of Dentistry, for her important assistance in preparation of samples for histology and immunohistochemistry. Mechanical tests were performed at the Faculty of Pharmacy of University of Porto.

References

- 1.Pountos I, Jones E, Tzioupis C, McGonagle D, Giannoudis PV. Growing bone and cartilage. The role of mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(4):421–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.17060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman AP. Articular cartilage repair. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(2):309–24. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260022701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomihisa K, Tomoo M, Toshitaka T, Tomoyuki S. New bone formation around porous hydroxyapatite wedge implanted in opening wedge high tibial osteotomy in patients with osteoarthritis. Biomaterials. 2001;22(12):1579–1582. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss P, Layrolle P, Clergeau LP, Enckel B, Pilet P, Amouriq Y, Daculsi G, Giumelli B. The safety and efficacy of an injectable bone substitute in dental sockets demonstrated in a human clinical trial. Biomaterials. 2007;28(22):3295–3305. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verlaan JJ, Oner FC, Dhert WJ. Anterior spinal column augmentation with injectable bone cements. Biomaterials. 2006;27(3):290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zelzer E, Olsen BR. The genetic basis for skeletal diseases. Nature. 2003;423(6937):343–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivaska KK, Gerdhem P, Åkesson K, Garnero P, Obrant KJ. Effect of Fracture on Bone Turnover Markers: A Longitudinal Study Comparing Marker Levels Before and After Injury in 113 Elderly Women. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2007;22(8):1155–1164. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunziker EB. Articular cartilage repair: basic science and clinical progress. A review of the current status and prospects. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10(6):432–63. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curran SJ, Chen R, Curran JM, Hunt JA. Expansion of human chondrocytes in an intermittent stirred flow bioreactor, using modified biodegradable microspheres. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(9–10):1312–22. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinatier C, Magne D, Moreau A, Gauthier O, Malard O, Vignes-Colombeix C, Daculsi G, Weiss P, Guicheux J. Engineering cartilage with human nasal chondrocytes and a silanized hydroxypropyl methylcellulose hydrogel. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2007;80A(1):66–74. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pound JC, Green DW, Chaudhuri JB, Mann S, Roach HI, Oreffo RO. Strategies to promote chondrogenesis and osteogenesis from human bone marrow cells and articular chondrocytes encapsulated in polysaccharide templates. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(10):2789–99. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasten P, Vogel J, Luginbuhl R, Niemeyer P, Tonak M, Lorenz H, Helbig L, Weiss S, Fellenberg J, Leo A, et al. Ectopic bone formation associated with mesenchymal stem cells in a resorbable calcium deficient hydroxyapatite carrier. Biomaterials. 2005;26(29):5879–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JY, Musgrave D, Pelinkovic D, Fukushima K, Cummins J, Usas A, Robbins P, Fu FH, Huard J. Effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2-expressing muscle-derived cells on healing of critical-sized bone defects in mice. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(7):1032–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sumanasinghe RD, Osborne JA, Loboa EG. Mesenchymal stem cell-seeded collagen matrices for bone repair: Effects of cyclic tensile strain, cell density, and media conditions on matrix contraction in vitro. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2008;88A(3):778–786. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alsberg E, Anderson KW, Albeiruti A, Rowley JA, Mooney DJ. Engineering growing tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(19):12025–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192291499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arpornmaeklong P, Suwatwirote N, Pripatnanont P, Oungbho K. Growth and differentiation of mouse osteoblasts on chitosan-collagen sponges. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2007;36(4):328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lode A, Bernhardt A, Gelinsky M. Cultivation of human bone marrow stromal cells on three-dimensional scaffolds of mineralized collagen: influence of seeding density on colonization, proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2008;2(7):400–407. doi: 10.1002/term.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balooch M, Habelitz S, Kinney JH, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. Mechanical properties of mineralized collagen fibrils as influenced by demineralization. Journal of Structural Biology. 2008;162(3):404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelse K, Poschl E, Aigner T. Collagens-structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55(12):1531–46. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berglund JD, Mohseni MM, Nerem RM, Sambanis A. A biological hybrid model for collagen-based tissue engineered vascular constructs. Biomaterials. 2003;24(7):1241–54. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chvapil M. Collagen sponge: theory and practice of medical applications. J Biomed Mater Res. 1977;11(5):721–41. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820110508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chvapil M, Kronenthal L, Van Winkle W., Jr Medical and surgical applications of collagen. Int Rev Connect Tissue Res. 1973;6:1–61. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-363706-2.50007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matton G, Anseeuw A, De Keyser F. The history of injectable biomaterials and the biology of collagen. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1985;9(2):133–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01570345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radhika M, Babu M, Sehgal PK. Cellular proliferation on desamidated collagen matrices. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1999;124(2):131–9. doi: 10.1016/s0742-8413(99)00042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elliott JT, Woodward JT, Langenbach KJ, Tona A, Jones PL, Plant AL. Vascular smooth muscle cell response on thin films of collagen. Matrix Biol. 2005;24(7):489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song J, Rolfe BE, Hayward IP, Campbell GR, Campbell JH. Effects of collagen gel configuration on behavior of vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro: association with vascular morphogenesis. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2000;36(9):600–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02577528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinberg CB, Bell E. A blood vessel model constructed from collagen and cultured vascular cells. Science. 1986;231(4736):397–400. doi: 10.1126/science.2934816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid GG, Gorham SD, Lackie JM. The Attachment, Spreading and Growth of Baby Hamster-Kidney Cells on Collagen, Chemically Modified Collagen and Collagen-Composite Substrata. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine. 1993;4(2):201–209. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michalopoulos G, Pitot HC. Primary culture of parenchymal liver cells on collagen membranes. Morphological and biochemical observations. Exp Cell Res. 1975;94(1):70–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(75)90532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winder SJ, Turvey A, Forsyth IA. Characteristics of ruminant mammary epithelial cells grown in primary culture in serum-free medium. J Dairy Res. 1992;59(4):491–8. doi: 10.1017/s0022029900027151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato T, Chen G, Ushida T, Ishii T, Ochiai N, Tateishi T. Tissue-engineered cartilage by in vivo culturing of chondrocytes in PLGA-collagen hybrid sponge. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2001;17(1–2):83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahiro O, Keizo T, Yosuke H, Takashi U, Tamotsu T, Tetsuya T. Effect of type I and type II collagen sponges as 3D scaffolds for hyaline cartilage-like tissue regeneration on phenotypic control of seeded chondrocytes in vitro. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2004;24(3):407–411. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuchs JR, Kaviani A, Oh JT, LaVan D, Udagawa T, Jennings RW, Wilson JM, Fauza DO. Diaphragmatic reconstruction with autologous tendon engineered from mesenchymal amniocytes. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kall S, Nöth U, Reimers K, Choi CYU, Muehlberger T, Allmeling C, Jahn S, Heymer A, Vogt PM. In Vitro Fabrication of Tendon Substitutes Using Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells and a Collagen Type I Gel. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2004;4:205–211. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Domaschke H, Gelinsky M, Burmeister B, Fleig R, Hanke T, Reinstorf A, Pompe W, Rosen-Wolff A. In Vitro Ossification and Remodeling of Mineralized Collagen I Scaffolds. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12(4):949–958. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodrigues CVM, Serricella P, Linhares ABR, Guerdes RM, Borojevic R, Rossi MA, Duarte MEL, Farina M. Characterization of a bovine collagen-hydroxyapatite composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2003;24(27):4987–4997. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooperman L, Michaeli D. The immunogenicity of injectable collagen. I. A 1-year prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10(4):638–46. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeLustro F, Condell RA, Nguyen MA, McPherson JM. A comparative study of the biologic and immunologic response to medical devices derived from dermal collagen. J Biomed Mater Res. 1986;20(1):109–20. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandberg M, Vurio E. Localization of types I, II, and III collagen mRNAs in developing human skeletal tissues by in situ hybridization. J Cell Biol. 1987;104(4):1077–1084. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeLustro F, Smith ST, Sundsmo J, Salem G, Kincaid S, Ellingsworth L. Reaction to injectable collagen: results in animal models and clinical use. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79(4):581–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynn AK, Yannas IV, Bonfield W. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of collagen. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2004;71B(2):343–354. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizuno M, Shindo M, Kobayashi D, Tsuruga E, Amemiya A, Kuboki Y. Osteogenesis by bone marrow stromal cells maintained on type I collagen matrix gels in vivo. Bone. 1997;20(2):101–107. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(96)00349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wambach BA, Cheung H, Josephson GD. Cartilage Tissue Engineering Using Thyroid Chondrocytes on a Type I Collagen Matrix. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(12):2008–2011. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajpurohit R, Koch CJ, Tao Z, Teixeira CM, Shapiro IM. Adaptation of chondrocytes to low oxygen tension: relationship between hypoxia and cellular metabolism. J Cell Physiol. 1996;168(2):424–32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199608)168:2<424::AID-JCP21>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schipani E, Ryan HE, Didrickson S, Kobayashi T, Knight M, Johnson RS. Hypoxia in cartilage: HIF-1 alpha is essential for chondrocyte growth arrest and survival. Genes & Development. 2001;15(21):2865–2876. doi: 10.1101/gad.934301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maes C, Carmeliet P, Moermans K, Stockmans I, Smets N, Collen D, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G. Impaired angiogenesis and endochondral bone formation in mice lacking the vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms VEGF164 and VEGF188. Mech Dev. 2002;111(1–2):61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petersen W, Tsokos M, Pufe T. Expression of VEGF121 and VEGF165 in hypertrophic chondrocytes of the human growth plate and epiphyseal cartilage. J Anat. 2002;201(2):153–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliveira SM, Amaral IF, Barbosa MA, Teixeira CC. Engineering endochondral bone: In vitro studies. Tissue Engineering. 2009;15(3):625–634. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teixeira CC, Nemelivsky Y, Karkia C, Legeros RZ. Biphasic calcium phosphate: a scaffold for growth plate chondrocyte maturation. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12(8):2283–9. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliveira SM, Turner G, Mijares D, Amaral IF, Barbosa MA, Teixeira CC. Engineering endochondral bone: In vivo studies. Tissue Engineering. 2009;15(3):635–643. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hiraoka Y, Kimura Y, Ueda H, Tabata Y. Fabrication and Biocompatibility of Collagen Sponge Reinforced with Poly(glycolic acid) Fiber. Tissue Engineering. 2003;9(6):1101–1112. doi: 10.1089/10763270360728017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yost MJ, Baicu CF, Stonerock CE, Terracio L. A Novel Tubular Scaffold for Cardiovascular Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering. 2004;10 (1–2):273–284. doi: 10.1089/107632704322791916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression? Theory and experiments. J Biomech Eng. 1980;102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwamoto M, Shapiro IM, Yagami K, Boskey AL, Leboy PS, Adams SL, Pacifici M. Retinoic acid induces rapid mineralization and expression of mineralization-related genes in chondrocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1993;207(2):413–20. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teixeira CC, Hatori M, Leboy PS, Pacifici M, Shapiro IM. A rapid and ultrasensitive method for measurement of DNA, calcium and protein content, and alkaline phosphatase activity of chondrocyte cultures. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995;56(3):252–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00298620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leboy PS, Vaias L, Uschmann B, Golub E, Adams SL, Pacifici M. Ascorbic acid induces alkaline phosphatase, type X collagen, and calcium deposition in cultured chick chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(29):17281–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whyte MP. Hypophosphatasia and the role of alkaline phosphatase in skeletal mineralization. Endocr Rev. 1994;15(4):439–61. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-4-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W, Kirsch T. Retinoic acid stimulates annexin-mediated growth plate chondrocyte mineralization. J Cell Biol. 2002;157(6):1061–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone Morphogenetic Proteins. Growth Factors. 2004;22(4):233–241. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gerstenfeld LC, Shapiro FD. Expression of bone-specific genes by hypertrophic chondrocytes: Implications of the complex functions of the hypertrophic chondrocyte during endochondral bone development. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1996;62(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(199607)62:1%3C1::AID-JCB1%3E3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bianco P, Cancedda FD, Riminucci M, Cancedda R. Bone formation via cartilage models: The “borderline” chondrocyte. Matrix Biology. 1998;17(3):185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Bernard B, Bianco P, Bonucci E, Costantini M, Lunazzi GC, Martinuzzi P, Modricky C, Moro L, Panfili E, Pollesello P. Biochemical and immunohistochemical evidence that in cartilage an alkaline phosphatase is a Ca 2′-binding glycoprotein. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1615–1623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Galotto M, Campanile G, Robino G, Cancedda FD, Bianco P, Cancedda R. Hypertrophic chondrocytes undergo further differentiation to osteoblast-like cells and participate in the initial bone formation in developing chick embryo. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1239–1249. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mark MP, Butler WT, Prince CW, Finkelman RD, Ruch JV. Developmental expression of 44-kDa bone phosphoprotein (osteopontin) and bone gamma-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla)-containing protein (osteocalcin) in calcifying tissues of rat. Differentiation. 1988;37(2):123–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1988.tb00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sims CD, Butler PE, Casanova R, Lee BT, Randolph MA, Lee WP, Vacanti CA, Yaremchuk MJ. Injectable cartilage using polyethylene oxide polymer substrates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(5):843–50. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199610000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woodard JC, Donovan GA, Fisher LW. Pathogenesis of vitamin (A and D)-induced premature growth-plate closure in calves. Bone. 1997;27:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liao E, Yaszemski M, Krebsbach P, Hollister S. Tissue-engineered cartilage constructs using composite hyaluronic acid/collagen I hydrogels and designed poly(propylene fumarate) scaffolds. Tissue Engineering. 2007;13:537–550. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gerstenfeld LC, Cruceta J, Shea CM, Sampath K, Barnes GL, Einhorn TA. Chondrocytes provide morphogenic signals that selectively induce osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(2):221–30. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]