Abstract

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) expression correlates with metastatic medulloblastoma. PDGF stimulation of medulloblastoma cells phosphorylates Erk and promotes migration. We sought to determine whether blocking PDGFR activity effectively inhibits signaling required for medulloblastoma cell migration and invasion. DAOY and D556 human medulloblastoma cells were treated with imatinib mesylate (Gleevec®), a PDGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, or transfected with siRNA to PDGFRB to test the effects of blocking PDGFR phosphorylation and expression, respectively. PDGFR cell signaling, migration, invasion, survival and proliferation following PDGF-BB stimulation, with and without PDGFR inhibition, were measured. PDGF-BB treatment of cells increased PDGFRB, Akt and Erk phosphorylation, and transactivated EGFR, which correlated with enhanced migration, survival and proliferation. Imatinib (1 uM) treatment of DAOY and D556 cells inhibited PDGF-BB- and serum-mediated migration and invasion at 24 h and 48 h, respectively, and concomitantly inhibited PDGF-BB activation of PDGFRB, Akt and Erk, but induced increased PTEN expression and activity. Imatinib treatment also induced DAOY cell apoptosis at 72 h and inhibited DAOY and D556 cell proliferation at 48 h. siRNA silencing of PDGFRB similarly inhibited signaling, migration and survival and both siRNA and imatinib treatment inhibited PDGF-BB-mediated EGFR transactivation, indicating that the effects of imatinib treatment are specific to PDGFRB target inhibition. These results indicate that PDGFRB tyrosine kinase activity is critical for migration and invasion of medulloblastoma cells, possibly by transactivating EGFR, and thus imatinib may represent an important novel therapeutic agent for the treatment of medulloblastoma.

Keywords: Medulloblasotma, Imatinib mesylate, PDGFR, EGFR, PTEN

Introduction

Medulloblastoma has a tendency to disseminate throughout the central nervous system (CNS) early in the course of illness (1). Because of this risk, treatment for medulloblastoma involves prophylactic craniospinal irradiation, except in very young children, and chemotherapy, which together are responsible for significant long-term morbidity, including severe neurocognitive impairment (1–4). Less toxic tumor-targeting treatment strategies designed to prevent metastases are thus imperative.

We previously reported that the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and PDGFR downstream effectors within the Ras-Erk signal transduction pathways are significantly up-regulated in metastatic medulloblastoma, suggesting that PDGFR may be a therapeutic target (5, 6). PDGFR has been implicated in the metastasis of a variety of cancers (7–13). Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec or STI-571) is an inhibitor of the receptor tyrosine kinases Bcr-Abl, PDGFR and c-Kit, a proto-oncogene expressed by medulloblastomas that has also been associated with metastasis (14). Matei et al. showed that imatinib inhibits ovarian cancer cell growth in a PDGFR-specific manner, at clinically relevant concentrations (IC50 < 1 μM) (15). Imatinib treatment of glioblastoma cells (U343 and U87), which exhibit PDGFR autocrine signaling, inhibited tumor cell growth in vitro as well as in mice bearing intracranial xenografts (16).

Whether imatinib similarly inhibits PDGFR signaling and cellular functions relevant to the promotion of medulloblastoma metastasis is unknown. Because of the association of the PDGFR pathway with medulloblastoma metastasis, coupled to the critical need for tumor-specific therapeutics against this disease in children, we investigated the effects of imatinib on PDGFR-mediated medulloblastoma cell migration, invasion and growth.

Materials and Methods

Cells

DAOY and D556 human medulloblastoma cells were investigated. DAOY expresses moderate levels of ERBB2 (17) and PDGFRB protein, while D556 expresses high levels of PDGFRB. Both cells are considered highly migratory in that DAOY closely resembles metastatic tumors by RNA profiling (5) and is metastatic in vivo (18), while D556 is amplified for MYCC and is derived from an anaplastic medulloblastoma, a clinically aggressive tumor subtype with higher frequency of metastases. Neither cell has known p53 gene mutations or expression of Bcr-Abl (19). Cells were grown in T-75cm flasks in EMEM (Biowhitaker) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37° C with 5 % CO2 according to the specifications of the American Type Culture Collection.

siRNA transfection

Cells were grown until 50–60 % confluence, washed with PBS and grown in serum-free media overnight. Cells were then washed with Opti-Mem and transfected with PDGFRB or negative control siRNA oligonucleotides (Dharmacon, Chicago, IL) in serum-free Opti-Mem to a final concentration of 100 nM. Lipofectamine 2000 (L2K) was used at 0.1 % final volume in serum-free Opti-Mem. siRNA/Opti-Mem and L2K/Opti-Mem dilutions were mixed together by gentle inversion and incubated at RT for 25 min before adding to the cells. After 24 h, cells were washed with PBS and cultured in serum-free media for 24 h before PDGF stimulation and Western blot analysis.

Imatinib treatment

The aim of these experiments was to determine 1) the magnitude of the effect of PDGF on downstream signaling and resultant cellular events and 2) the efficacy of imatinib in blocking these specific PDGF-induced events. The latter experiment was performed by treatment with imatinib first and then PDGF stimulation in order to more precisely measure the efficacy of imatinib. Because imatinib acts by preventing PDGF-induced PDGFR autophosphorylation, if cells are stimulated with PDGF first, then the PDGFR signal transduction cascade will be initiated and some of the downstream cellular events will occur as a result of this propagated signal despite subsequent imatinib treatment. Although there may still be an effect of imatinib on PDGFR due to unbound PDGF (i.e. autocrine activation) it would be difficult to interpret the precise effect of imatinib inhibition of PDGF-induced events at this point.

Cells were cultured until 80% confluence, washed with serum-free media and serum-starved overnight. Cells were treated with either vehicle (sterile H2O) control or imatinib (Novartis, Cambridge, MA). For the dose-curve studies, cells were treated with increasing amounts of imatinib (0–2 uM) for 1 h, then stimulated with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) for 12 min. For the time-curve studies, cells were treated with 1 uM imatinib for specific time points. Cells were maintained in serum-free media and imatinib was not replenished after the initial dose prior to lysing cells for Western blot analysis of PDGFR pathway activation.

PDGF and EGF stimulation

Cells (1×106) were serum-starved for 24 h, washed with serum-free media to remove endogenous growth factors, replenished with serum-free media and then treated with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml), the amount of PDGF determined for maintaining maximum PDGFR phosphorylation over 24 h, or control PBS for 12 min prior to lysing cells for Western blot analysis of PDGFR pathway activation. The amount of PDGF-BB was doubled (20 ng/ml) for assays requiring at least 48 h incubation (i.e. invasion and proliferation) to ensure that receptors remained maximally saturated with ligand for the entire period of the experiment. For EGFR direct activation studies, 50 ng/ml EGF (Cat # 236-EG, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used in place of PDGF.

Western blot

Whole cell lysates were prepared from cells lysed in 500 μl of 1 X Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford dye-binding assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). An aliquot of the lysate was mixed with an equal volume of 2 X laemmli sample buffer and heated at 97° C for 10 min. 40–80 μg of total protein was electrophoresed on a 7.5 % SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Target proteins were detected using primary antibodies for total or phosphorylated forms of PDGFRB (Cat no. 4564, 3161; lot # 6, 4; 1:500, 1:250 dilution, respectively), PI3K (Cat no. 4292, 4228; lot # 4, 2; 1:500, 1:250 dilution, respectively), PTEN (Cat no. 9552, 9551; lot # 2, 5; 1: 500 dilution), Akt (Cat no. 9272, 2336; lot # 18, 11; 1:500, 1:250 dilution, respectively), Erk1/2 (Cat no. 4695, 4377; lot # 4, 2; 1:500, 1:250 dilution, respectively) and EGFR (Cat no. 2646, 4407; lot # 4, 4; 1:500, 1:250 dilution, respectively) (Cell Signaling Technology). The blots were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4° C, washed and incubated with anti-rabbit IgG HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), diluted 1:2000 for 1 h at RT. Blots were washed with 1 x TBS-Tween (0.1 %) and incubated with SuperSignal Dura chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) ~2 min and then exposed. To control for protein loading, primary antibodies for actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology) were used, while the total protein for PDGFRB, EGFR, PI3K, Akt and Erk1/2 was used to measure the total:phosphorylated protein ratio, quantitated by densitometric analysis using software from Scion Corporated. Because PDGF-BB and imatinib treatment altered total PTEN expression, GAPDH, which was not altered by either treatment, was used to normalize changes in PTEN phosphorylation.

PDGFRB-EGFR co-immunoprecipitation

Imatinib-treated cells stimulated with PDGF-BB were cross-linked, lysed and PDGFRB co-immunoprecipitated with EGFR using a rabbit polyclonal anti-human PDGFRB antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoprecipitates were run on an SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The blot was blocked for 1 h in 5% BSA and probed with a rabbit polyclonal anti-human phospho-specific EGFR antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). After overnight incubation with the primary antibody, the blot was washed and incubated with anti-rabbit IgG HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) diluted 1:2000 for 1 h at RT. The blot was washed with 1 X TBS-Tween (0.1%) and incubated with SuperSignal Dura chemiluminescent substrate ~2 min and exposed for PDGFRB-EGFR heterodimer detection.

Ras activation assay

Ras-GTP was precipitated from total cell lysates using a Ras activation assay kit (Millipore Corporation, Temecula, CA; Cat # 17–424) according to the manufacturer’s manual. Briefly, 500 ul of total cell lysate was incubated with 20 ul of the Ras assay reagent (Raf-1 RBD, agarose) for 45 min at 4° C with gentle agitation. The agarose beads were pelleted by brief centrifugation and supernatant discarded. Beads were washed (3 X) with 500 ul wash buffer, taking care to minimize loss of beads during removal of the wash buffer. Agarose beads were resuspended in 40 ul of 2 X laemmli reducing sample buffer, boiled for 5 min and pelleted by brief centrifugation. The supernatant (20 ul) was electrophoresed on a SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk and 3% BSA in 0.1% TBS-T (1X), and incubated overnight with anti-Ras (clone Ras10) at 4°C. The membrane was washed with 0.1% TBS-T and incubated 1 h with anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, CA). The membrane was washed with 0.1% TBS-T and protein detected using SuperSignal Dura chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

Migration assays

Transwell migration assays were used to assess the short-term effects of PDGF and imatinib on cell migration. Serum-deprived DAOY and D556 cells were treated with 1 uM imatinib or vehicle control for 1 h, harvested, and resuspended to 1×106 cells in the upper well of a fibronectin-coated Transwell migration chamber (Millipore; Cat # ECM580). The lower well of the chamber contained serum-free media or serum-free media supplemented with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB. After 4 h incubation, non-migrating cells were removed with a cotton swab and migrating cells on the underside of the membrane were stained with cell stain solution (Millipore) for 10 min. The stain was removed with extraction buffer (Millipore) and 100 ul of the dye was quantitated using a colorimetric microplate reader (OD 570 nm).

Wound migration assays were used to assess the longer-term effects of PDGF and imatinib on cell migration, which compared to the Transwell assay are potentially more physiologically relevant and allow for testing of more durable effects of imatinib on migration. DAOY and D556 cells were grown in a Petri dish to 70–80% confluence, washed and serum-starved overnight and then treated with either vehicle control or 1 uM imatinib for 1 h. After treatment, cells were scraped using a 1 ml pipette to induce a ‘wound’. The scraped off cells were washed out using serum-free media and fresh media was replenished containing 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB supplemented with the same concentration of imatinib. Images of 10–12 random fields in the scraped wound were taken at the time of wound induction (0 h) and 24 h after. The area of the wound was traced and measured in micron2 using Axiovision systems. The average area in micron2 of the wound at 24 h was subtracted from the area at 0 h and graphed using Microsoft excel.

Invasion assay

24-well ECMatrix-coated invasion chambers (Millipore; Cat # ECM550) were used according to the manufacturer’s directions. Serum-starved cells (1×105) were plated in the top well of an ECMatrix-coated invasion chamber. The bottom chamber contained PDGF-BB (20 ng/ml) or PBS negative control as chemo-attractant. Cells were incubated for 48 h to allow sufficient time for invasion. After 48 h incubation, non-invading cells were removed with a cotton swab and the invading cells that had crossed the ECMatrix to the underside of the membrane were stained with cell stain solution. The stain was removed with extraction buffer and 100 ul of the dye solution was quantitated using a colorimetric microplate reader (OD 570 nm).

Apoptosis analysis

Imatinib-treated cells were trypsinized, washed with 1% BSA-PBS and incubated in 100 ul of 1X Annexin V staining buffer, 7-AAD and Annexin V APC diluted 1:40 for 15 min. After incubation, 250 ul of Annexin V buffer was added to each tube and cells acquired within 1 h. The following control conditions were analyzed: 1) unstained cells; 2) cells + 7AAD; 3) cells + Annexin V; 4) unstained imatinib-treated cells: 5) imatinib-treated cells + 7AAD; 6) imatinib-treated cells + Annexin V.

Caspase-3 and -8 assays

Serum-deprived DAOY and D556 cells were treated with 1 uM imatinib and cultured for 48 h. Caspase-3 and -8 cellular activity was detected at 24 and 48 h after treatment. For caspase-3 assessment, cells were trypsinized, counted and resuspended in 80 ul of 1X Lysis Buffer (0.5 × 106 cells) for 10 min, centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min and supernatants transferred to fresh tubes and protein concentration determined. One hundred micrograms of total protein lysates were incubated with caspase-3 substrate (Millipore, Cat # APT300) for 1 h in a 96-well plate. For negative control a portion of the cell lysate was incubated with caspase-3 inhibitor for 10 min before adding the caspase-3 substrate. For positive control, caspase-3 human recombinant enzyme was used at 2, 1, 0.5, and 0.25 Units with or without the inhibitor. After incubation with the caspase-3 substrate, a colorimetric microplate reader was used to detect the presence of caspase-3 (OD 405 nm). For caspase-8 assessment, cells were stained with FLICA reagent and Hoechst stain (Millipore, Cat # APT428) and examined under an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Proliferation assays

FACS analysis of Ki-67 immunostaining was used to assess the effects of PDGF and imatinib treatment on proliferation over 48 h. After PDGF-BB (20 ng/ml) stimulation of 1 uM imatinib- or vehicle control-treated serum-depleted cells for 1h, cells were harvested at specific time points, washed with 1% PBS-BSA, resuspended in 200 ul PBS then slowly added to ice-cold 70–80% ethanol while vortexing and incubated at −20° C for 2 h. Cells were washed with 1% PBS-BSA, centrifuged at 5° C for 10 min, resuspended in 200 ul 1% PBS-BSA containing Ki-67 antibody (1:40)(BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and incubated at RT for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS, centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min, supernatant discarded and cells resuspended in 200 ul 1% PBS-BSA containing propidium iodide (PI) (1:40) before acquiring cells in FACS-calibur. Controls used were 1) unstained cells, 2) cells stained with Ki-67 only and 3) cells stained with PI only.

Direct cell counting was used as an alternative method to validate the effects of PDGF and imatinib treatment on cell viability and proliferation and to assess these effects over a longer period of time. After imatinib treatment and PDGF-BB stimulation as described, cells were harvested at specific time points, resuspended in serum-free media and 10 ul of the cell suspension was stained with 10 ul trypan blue (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) and viable cells were counted on a hemocytometer. Viable cells were counted at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after imatinib treatment.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were conducted in triplicates and the mean of all three experiments was calculated and plotted ± the standard error of the means. A two-sided Student’s t test was used to determine statistical significance between groups. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to test for significant differences among means of multiple groups obtained from three or more independent experiments. The means of three or more independent experiments ± the standard error of the means were derived and graphed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Imatinib inhibits PDGFRB activation and signal transduction in medulloblastoma cells

One-hour imatinib treatment of serum-starved DAOY (Fig. 1A) and D556 (supplemental Fig. 1A) human medulloblastoma cells stimulated with PDGF-BB resulted in a concentration-dependent inhibition of PDGFRB phosphorylation. PDGFRB phosphorylation was abolished in both cells with 1 uM of imatinib. In a time-course study, a single dose of imatinib (1 uM) inhibited PDGFR phosphorylation in both cells for 144 h after treatment (data not shown). Imatinib treatment also inhibited PDGFR downstream signal transduction of DAOY (Fig. 1A) and D556 cells (supplemental Fig. 1A), which lasted up to 48 h (data not shown) after a single 1 uM dose. PDGFRB phosphorylation was also inhibited in medulloblastoma cells grown in 10% serum (supplemental Fig. 1B). Imatinib similarly inhibited PDGF-BB activation of Akt and Erk; however, activation of these downstream effectors could not be abolished, suggesting that Akt and Erk activation is not PDGF-dependent in DAOY (Fig. 1A and B) and D556 (supplemental Fig. 1C) cells. DAOY and D556 cells treated with 1 uM Imatinib for 1 h showed no significant difference in total or active Ras protein expression compared to untreated PDGF-stimulated control cells, indicating that the inhibitory effect of imatinib on PDGF-induced Akt and Erk activation is Ras-independent (Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 1. Imatinib inhibits medulloblastoma cell Akt and Erk1/2 activation in a Ras-independent manner.

Serum-starved medulloblastoma cells were first treated with increasing concentrations of imatinib or vehicle control (‘0’) for 1 h before stimulation with PDFG-BB (10 ng/ml). After an optimal dose of imatinib was identified, cells were treated with (‘+’) or without (‘−’) imatinib and PDGF-BB. Changes in target proteins and phosphorylation were detected by Western blot. A, Representative Western blot of imatinib-treated DAOY cells shows reduced activation (phosphorylation) of PDGFRB and the downstream signal transduction effectors Akt and Erk in a dose-dependent manner compared to control cells stimulated with PDGF-BB. B, Densitometry of multiple corresponding Western blots confirms significant inhibition (P < 0.005) of Akt and Erk phosphorylation in PDGF-BB stimulated DAOY cells treated with 1 uM imatinib. C, Representative Western blot of total Ras in DAOY cells treated with increasing concentrations of imatinib and D, Densitometry of multiple corresponding Western blots for GTP-Ras (DAOY and D556) following 1 uM imatinib treatment shows that Ras expression and activity is not significantly changed following imatinib treatment and PDGF-BB stimulation. *, Indicates statistically significant decrease in PDGF-BB-mediated Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation after imatinib treatment compared to untreated control cells. Results represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean of multiple experiments.

Imatinib increases PTEN activity in PDGF-stimulated medulloblastoma cells

PTEN, a downstream effector of PDGFR, is a negative regulator of PI3K activation of Akt. PTEN is over expressed in DAOY relative to D556 cells (supplemental Fig. 2). To determine whether PTEN activity changes in accordance with imatinib-mediated inhibition of Akt, we examined PTEN expression and phosphorylation after 1 uM imatinib treatment for 1 h. Imatinib treatment resulted in increased PTEN expression and phosphorylation, but only in PDGF-stimulated Daoy cells (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Imatinib treatment increases PTEN expression and activity in DAOY medulloblastoma cells stimulated with PDGF-BB.

Serum-deprived DAOY cells were treated with (‘+’) 1 uM imatinib or vehicle control (‘−’) for 1 h before stimulation with (‘+’) or without (‘−’) PDFG-BB (10 ng/ml). Changes in PTEN protein and phosphorylation were detected by Western blot. Representative Western blots show A, PTEN expression and B, PTEN phosphorylation is increased in imatinib-treated cells stimulated with PDGF-BB compared to untreated control cells. C and D, Densitometric analysis of multiple corresponding Western blots confirms significantly (indicated by *) higher levels (P < 0.05) of total and phosphorylated PTEN, respectively, in imatinib-treated cells stimulated with PDGF-BB compared to untreated control cells. Results represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean of multiple experiments.

Imatinib inhibits PDGFR-mediated EGFR transactivation in medulloblastoma cells

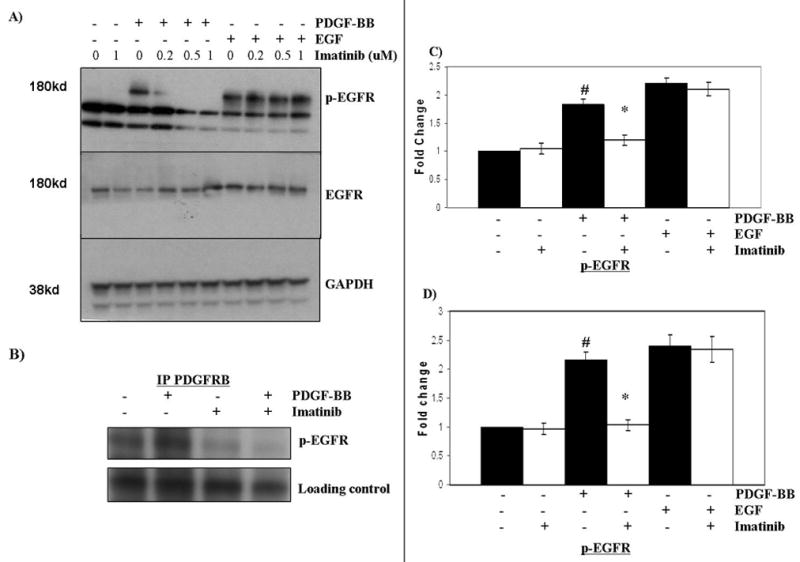

Saito et al. previously showed that the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) can be transactivated by PDGF stimulation in rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells and that EGFR transactivation is necessary for PDGF-mediated migration of these cells (19). To test whether PDGF similarly transactivates EGFR in medulloblastoma cells, cells were stimulated with PDGF-BB and probed for phospho-EGFR. PDGF-BB stimulation significantly transactivated EGFR in DAOY (Fig. 3A) and D556 (supplemental Fig. 3B) cells. In the study by Saito et al., it was concluded that PDGFRB tyrosine kinase activity was not required for EGFR transactivation since inhibition of PDGFRB phosphorylation by AG1295 did not affect PDGF-mediated EGFR activation, but instead was blocked by disruption of PDGFR-EGFR formed heterodimers. We found by co-immunoprecipitation that PDGF-BB stimulated cells formed PDGFRB-EGFR heterodimers, more so than that observed in unstimulated cells; however, in contrast to the study by Saito et al., EGFR transactivation and PDGF-induced heterodimers were abolished in a dose-dependent manner after imatinib treatment, suggesting that PDGFR autophosphorylation is necessary for heterodimerization with EGFR and EGFR transactivation in medulloblastoma cells (Fig. 3A and B). To ensure that imatinib was not directly impacting EGFR activation, cells were treated for 1 h with imatinib and stimulated with EGF. We show that imatinib treatment does not inhibit EGF-mediated EGFR phosphorylation, confirming PDGFRB-mediated transactivation of EGFR in DAOY (Fig. 3A and C) and D556 cells (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Imatinib abolishes PDGF-BB-mediated EGFR transactivation in medulloblastoima cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Serum-starved DAOY cells were treated with increasing doses of imatinib or vehicle control (‘0’) for 1 h before stimulation with (‘+’) or without (‘−’) PDFG-BB (10 ng/ml) or EGF (50 ng/ml). Changes in target proteins and phosphorylation were detected by Western blot and co-immunpreciptation was used to detect PDGFR-EGFR heterodimers. Representative Western blots show that A, Imatinib treatment inhibits PDGF-mediated transactivation of EGFR in a dose-dependent manner, but has no effect on EGF-mediated activation of EGFR and B, Imatinib (1 uM) treatment of PDGF-stimulated DAOY cells abolished the PDGFRB-phospho(p)-EGFR association compared to untreated (‘−’) control cells as detected by co-immunoprecipitation (blot was cropped to improve clarity; full-length blot is provided in supplemental Fig. 3A). C and D, Densitometry of multiple corresponding Western blots confirms that DAOY and D556 cells, respectively, have significantly reduced levels of PDGF-BB-mediated EGFR transactivation (P < 0.0005) following 1 uM imatinib treatment compared to untreated (‘−’) control cells. #, Indicates statistically significant increase in EGFR activation in cells stimulated with PDGF-BB compared to unstimulated cells; * indicates statistically significant decrease in PDGF-mediated EGFR transactivation in imatinib-treated cells compared to untreated control cells. Results represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean of multiple experiments.

siRNA to PDGFRB inhibits PDGF-mediated signal transduction in medulloblastoma cells

To confirm that the imatinib effects are directly attributable to PDGFRB inhibition rather than to inhibition of PDGFRA or c-Kit, another specific target of imatinib, or other off-target drug effects, DAOY and D556 cells were transfected with siRNA specifically targeting PDGFRB. Transfectants showed significant knock-down in total PDGFRB protein expression compared to cells transfected with a negative control, scrambled siRNA (supplemental Fig. 4A and C), and similar to imatinib-treated cells, demonstrated complete inhibition of PDGFRB phosphorylation (supplemental Fig. 4B and C). PDGFRB knock-down was more effective in DAOY cells compared to D556 cells (supplemental Fig. 4A, Cand D), which express higher levels of endogenous PDGFRB relative to DAOY cells. Concomitant decrease in PDGF-BB-induced Akt and Erk phosphorylation was observed at 48 and 72 h after siRNA transfection of DAOY cells, yet similar to imatinib treatment, Akt and Erk activation could not be abolished (Fig. 4A). In siRNA treated D556 cells, which exhibited less PDGFRB knock-down, Akt and Erk phosphorylation was unaffected, indicating the siRNA effects appear to be specific and PDGFRB dose-dependent (data not shown). Total Ras expression in DAOY cells was decreased after siRNA treatment compared to cells transfected with a negative control siRNA (Fig. 4B). However, active GTP-Ras induction by PDGF, while relatively reduced in both DAOY and D556 cells with PDGFRB knock-down, did not reach statistical significance compared to negative control siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 4A and B). Thus, the effect of siRNA knock-down of PDGFRB on cellular function is believed to occur in a Ras-independent manner.

Figure 4. PDGFRB silencing by siRNA significantly reduces Akt and Erk1/2 activation in a Ras-independent manner, maintains PTEN and abolishes PDGF-BB-mediated EGFR trans-activation in medulloblastoma cells.

Medulloblastoma cells transfected with either PDGFRB siRNA (designated by ‘+’) or negative control siRNA (designated by ‘−’) were stimulated with (‘+’) or without (‘−’) PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) or EGF (50 ng/ml). Changes in target proteins and phosphorylation were detected by Western blot. DAOY and D556 cells transfected with PDGFRB siRNA showed significant knock-down of PDGFRB protein expression and activation (phosphorylation) (supplemental Fig. 4); Representative Western blots (upper panels) and densitometry of multiple corresponding Western blots (lower panels) show that A, DAOY cells with PDGFRB siRNA knock-down have significantly reduced levels of PDGF-activated Erk (P < 0.0005) and Akt (P < 0.005); B, Total Ras and GTP-Ras (active) expression levels were not significantly altered by PDGFRB siRNA knock-down (P > 0.05) in DAOY and D556 cells stimulated with PDGF-BB compared to control cells (‘−’); C, DAOY cells with PDGFRB siRNA knock-down maintained basal levels of total and phosphorylated PTEN, which were significantly higher compared to control siRNA transfected cells stimulated with PDGF-BB (P < 0.05) and D, DAOY (upper and lower panels) and D556 (lower panel) cells have significantly lower levels of PDGF-BB-mediated EGFR transactivation (P < 0.01) compared to negative control cells (‘−’). Results represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean of multiple experiments. *, Indicates statistically significant lower levels of PDGF-BB-mediated activation of Akt, Erk, and EGFR trans-activation, but higher levels of total and activated PTEN, in PDGFRB siRNA knock-down cells compared to negative control cells. #, Indicates statistically significant increase in PDGF-mediated EGFR transactivation in cells stimulated with PDGF-BB compared to unstimulated controls. Results represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean of multiple experiments.

siRNA knock-down of PDGFRB in PDGF-stimulated DAOY cells, but not D556, maintained expression and activation of PTEN and was increased relative to stimulated cells transfected with negative control siRNA (Fig. 4C), similar to the changes observed following imatinib treatment. PDGFRB knock-down in both DAOY (Fig. 4D) and D556 did not affect EGF-induced EGFR activation (supplemental Fig. 3B), but significantly reduced PDGF-BB-mediated transactivation of EGFR similar to imatinib (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4D).

Imatinib inhibits medulloblastoma cell migration and invasion

To determine whether imatinib affects medulloblastoma early cell migration, we used a haptotaxis cell migration assay. Cell migration after 4 h incubation with imatinib was significantly decreased (P < 0.05) in DAOY cells. D556 cells also exhibited a decrease in cell migration that reached near significance (P = 0.06) (Fig. 5A)

Figure 5. Imatinib inhibits medulloblastoma cell migration and invasion.

For short-term assessment of migration, serum-starved medulloblastoma cells were treated with either 1 uM imatinib (‘+’) or vehicle control (‘−’) for 1 h and then seeded into the upper well of a Transwell chamber with (‘+’) or without (‘−’) PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml)-containing media in the lower chamber as chemo-attractant and cell migration quantified after 4 h incubation. For longer-term assessment of migration, cells grown in culture dish were scraped, washed and imatinib-containing media replenished with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) or 10% FCS and then cells were allowed to fill in the wound over 24 h. Photomicrographs of the wound were taken at time of scraping and 24 h after. Invasion over 48 h was measured in a similar fashion to Transwell migration except ECMatrix chambers were used. A, Imatinib significantly inhibited PDGF-BB-mediated short-term cell migration of DAOY cells, and nearly significant for D556 (P = 0.05; P = 0.06, respectively), compared to control cells. B, Representative photomicrographs (10X, upper panel) and sum of calculated areas of corresponding wound closure from photomicrographs (lower panel) show that imatinib significantly inhibited PDGF-BB-mediated longer-term migration of DAOY and D556 cells (P < 0.01, each; lower-left panel) and significantly inhibited serum-mediated migration of DAOY and D556 cells compared to control cells (P < 0.005, each; lower-right panel). C, DAOY and D556 cells transfected with PDGFRB siRNA (+) showed significantly inhibited longer-term PDGF-mediated migration compared to cells transfected with negative control siRNA (−) (P < 0.05, each). D, Treatment with imatinib significantly inhibited the invasion of DAOY and D556 cells compared to negative control treated cells (P < 0.001, each). Results represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean of multiple experiments. *, Indicates a statistically significant decrease in cell migration or invasion of imatinib-treated cells compared to untreated control cells.

We further used an in vitro ‘wound healing assay’ to determine the effect of imatinib treatment on the migration of DAOY and D556 cells over a longer time interval (24 h) and in the presence of PDGF-BB alone or 10% serum. Imatinib treatment significantly decreased PDGF-BB-mediated migration of both DAOY (P = 0.0005) and D556 (P = 0.01) cells (Fig. 5B). Importantly, imatinib also significantly decreased migration of DAOY (P = 0.0001) and D556 (P = 0.0004) cells cultured in 10% serum (Fig. 5B), indicating that PDGFR plays a significant role overall in growth factor-mediated migration of medulloblastoma cells and that imatinib treatment is effective in preventing migration under more physiologic conditions of full serum.

Similar to imatinib treatment, PDGFRB siRNA transfected DAOY and D556 cells exhibited significantly decreased migration (P< 0.01) (Fig. 5C). Likewise, invasion was significantly decreased by imatinib treatment of DAOY and D556 (P = 0.0001, each) cells compared to controls (Fig. 5D), suggesting that PDGFR is similarly important for cell invasion.

Imatinib does not induce early apoptosis in medulloblastoma cells

To determine whether the inhibitory effect of imatinib on medulloblastoma migration at 4 and 24 h was due in part to an effect on survival, DAOY and D556 cells were analyzed for apoptosis at 24, 48 and 72 h after a single dose of imatinib. Imatinib induced a significant increase in apoptosis only at 72 h in DAOY cells compared to controls (28 % and 12 %, respectively; P < 0.05), and had no effect on D556 cells (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Imatinib induces delayed apoptosis and inhibits medulloblastoma cell proliferation.

Serum-starved medulloblastoma cells were treated with 1 uM imatinib (‘+’) or vehicle control (‘−’). Apoptosis was determined by 7-AAD/AnnexinV immunostaining and detection by FACS at 24, 48, and 72 h after a single dose of imatinib or 48 h after transfection with PDGFRB siRNA (‘+’) or negative control siRNA (‘−’). Cell proliferation was determined by the number of viable cells counted at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h after a single dose of imatinib. A, Imatinib treatment induced a significant increase in apoptosis only at 72 h after treatment in DAOY (P = 0.006, indicated by *), but not D556 cells, compared to untreated control cells. B, PDGFRB siRNA transfection resulted in a significant increase in apoptosis of DAOY (P = 0.002, indicated by *), but not D556 cells, compared to negative control transfected cells. C, Imatinib treatment of DAOY and D556 cells significantly reduced cell proliferation (P < 0.005, each, indicated by *) only at 72 h after treatment compared to untreated control cells. Results represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean of multiple experiments.

To assess whether DAOY cell apoptosis observed at 72 h was mediated via the caspase-3 or -8 pathway, imatinib treated cells were lysed at 24 and 48 h after treatment (prior to detectable apoptosis by immunostaining) and compared to controls. There was no detectable change in caspase-3 activity in either DAOY or D556 cells at 24 and 48 h after imatinib treatment (supplemental Fig. 5). DAOY cells were found to have inherently higher expression of caspase-8 compared to D556 cells; however, imatinib treatment also did not significantly alter caspase-8 activity in either cell either at 24 or 48 h after a single dose of imatinib (supplemental Fig. 6). Similarly, PDGFRB knock-down resulted in a significant increase in DAOY cell apoptosis at 48 h following transfection compared to control cells (45% and 20%, respectively; P = 0.002), while D556 cells did not exhibit any change (Fig. 6B). Together, these experiments confirm that imatinib’s effect on medulloblastoma cell migration is not due to induction of early apoptosis and that the mechanism of imatinib-induced delayed apoptosis in DAOY is caspase-3 and -8-independent.

Imatinib inhibits late, but not early, proliferation of medulloblastoma cells

To assess whether the effect of imatinib on medulloblastoma migration was in part due to inhibition of proliferation, we performed Ki-67 staining and direct cell counting of imatinib-treated DAOY and D556 cells. Imatinib treatment did not significantly decrease proliferation as indicated by Ki-67 staining in either cell at 24 and 48 h after treatment (data not shown). To validate the results of the Ki-67 proliferation assay, a cell viability assay was conducted. The cell viability assay showed similar results as the Ki-67 assay at 24 and 48 h after treatment; however, by 72 h after imatinib treatment, cell viability counts were significantly lower in both DAOY (P = 0.01) and D556 (P = 0.001) cells, indicating a delayed effect on viability with prolonged duration of inhibition (Fig. 6C). Despite higher levels of PDGFRB expression by D556 cells, imatinib treatment of both cells at the same concentration eliminated PDGFRB phosphorylation, suggesting that the concentration of imatinib used was likely in excess to occupy all the PDGFRB surface molecules (although not directly measured) in DAOY cells and sufficient to occupy enough of the PDGFRB molecules in both cells such that a phosphorylated PDGFRB signal was undetectable. The absence of detectable PDGFRB phosphorylation by imatinib in both cells allows for the accurate comparison of the relative changes in cellular functions (i.e. migration and proliferation) between cells stimulated with PDGF.

Discussion

We show that imatinib inhibition of PDGFR markedly impairs medulloblastoma cell migration and invasion in response to either PDGF or serum. The similar results observed between imatinib treatment and siRNA to PDGFRB confirms that the imatinib-induced effects are mediated specifically through PDGFRB inactivation, as opposed to PDGFRA inhibition, other known targets of imatinib or off-target drug effects, and that PDGFRB plays a critical role in medulloblastoma migration overall. Furthermore, we show that the mechanism of inhibition is Ras-independent, though likely mediated through Akt and Erk inactivation.

Differences in the survival responses to imatinib are likely due to underlying critical differences in the molecular genetic makeup of the two cell types. For instance, DAOY cells have high PTEN and p53 expression with no MYCC amplification, while D556 cells have low to absent PTEN and p53 expression with MYCC amplification. These effectors play important roles in the regulation of cell growth and survival and likely interact with PDGFR pathway signaling (20). Thus, finding that imatinib treatment of DAOY and D556 cells significantly decreased migration and invasion of both cell types, but induced apoptosis only of DAOY cells, further supports that PDGFRB likely plays a more vital role in the regulation of medulloblastoma migration irrespective of genetic predispositions.

Importantly, cell migration was also inhibited under more “physiologically relevant” conditions of full serum stimulation followed by imatinib treatment. In this setting, not only is the PDGFR pathway already activated, but also other potentially compensatory growth factor pathways are activated. While our results are similar to the findings of others, such as Servidei et al and McGary et al that showed an inhibitory effect of imatinib on glioma and osteosarcoma growth, respectively (21, 22), we chose to focus on the effect of imatinib on migration since the critical clinical problem with medulloblastoma is control of metastasis. PDGFR signaling and the resultant cellular events are cell-type specific and both pro- and anti-metastatic effects of PDGFR signaling have previously been described in differing malignant cells (23). Thomson et al. also showed that kinase inhibitors can have differing effects on different cell types (i.e. mesenchymal vs. epithelial) (24). Our results are thus specific to medulloblastoma and are novel in showing that imatinib inhibits medulloblastoma cell migration and invasion, the primary cellular events necessary for metastasis.

Our results are further novel in showing that imatinib treatment prevents PDGF-induced EGFR transactivation, while inducing relatively increased levels of PTEN expression and activity in medulloblastoma cells. The precise mechanism by which PDGF-BB induces EGFR transactivation in medulloblastoma cells remains to be determined, but it appears from our results that PDGFRB tyrosine kinase activity is required given that imatinib had no effect on EGF-mediated EGFR phosphorylation. The first study to demonstrate a functional cooperation between EGFR and PDGFRB for cell migration was conducted in murine fibroblasts (25). PDGF-induced migration correlated with EGFR phosphorylation and was abolished after expression of a catalytically inactive or truncated EGFR (25, 26). In our study, we detected PDGFRB-EGFR heterodimers and PDGFRB-phospho-EGFR heterodimers after PDGF-BB stimulation that were reduced after imatinib treatment. Previous reports have shown that PDGF can inhibit high affinity binding of EGF to EGFR in fibroblast cells and that EGFR and PDGFRB can be isolated together from caveolae-containing membrane fractions (27–29).

Together, our studies provide novel insight into the mechanisms of medulloblastoma migration and invasion and provide important pre-clinical evidence for the efficacy of imatinib to inhibit these functions. Further studies are required to confirm the entry of imatinib across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and its anti-tumour activity in vivo. In studies of patients and in vivo models with an intact BBB, the penetration of imatinib across the BBB has been shown to be relatively low; however, it is believed that in conditions in which the BBB is leaky (i.e. CNS tumors) the penetration of the drug is likely to be much greater. A report by Geng et al. showing that imatinib treatment of mouse GBM brain tumor models resulted in reduced phospho-PDGFR levels in GBM cells provides preclinical evidence in support of this hypothesis (30). In addition, a number of clinical reports demonstrating the efficacy of imatinib in brain tumor patients similarly support this argument (31, 32), indicating that further preclinical testing of imatinib treatment of medulloblastoma is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Imatinib was provided by Novartis Pharma. AG, Basel, Switzerland.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Tarik F. Haydar for revising the manuscript and Bhargavi Rajan, the senior FACS technician for her help in acquiring the cells for FACS analysis.

This work was supported by NIH R01 grant CA111835 (T.J.M.).

List of Abbreviations

- Akt

protein kinase B

- Bcr-Abl

breakpoint cluster region-Abelson fusion gene

- Erk

extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- c-Kit

cytokine cell surface receptor that binds stem cell factor

- CML

chronic myeloid leukemia

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PDGFR

platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3 kinase

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- Raf

serine/threonine-specific mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase

- Ras

low-molecular-weight GDP/GTP-binding guanine triphosphatase

References

- 1.Packer RJ, Cogen P, Vezina G, Rorke LB. Medulloblastoma: clinical and biologic aspects. Neuro-oncol. 1999;1:232–50. doi: 10.1215/15228517-1-3-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeltzer PM, Boyett JM, Finlay JL, et al. Metastasis stage, adjuvant treatment, and residual tumor are prognostic factors for medulloblastoma in children: conclusions from the Children’s Cancer Group 921 randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:832–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson DL, McCabe MA, Nicholson HS, et al. Quality of long-term survival in young children with medulloblastoma. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:1004–10. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ris MD, Packer R, Goldwein J, Jones-Wallace D, Boyett JM. Intellectual outcome after reduced-dose radiation therapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy for medulloblastoma. A Children’s Cancer Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3470–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald TJ, Brown K, LaFleur B, et al. Expression profiling of medulloblastoma. PDGFRA and the RAS/MAPK pathway as therapeutic targets for metastatic disease. Nat Genet. 2001;29:143–52. doi: 10.1038/ng731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbertson RJ, Clifford SC. PDGFRB is overexpressed in metastatic medulloblastoma. Nat Genet. 2003;35:197–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1103-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoch RV, Soriano P. Roles of PDGF in Animal Development. Development. 2003;130:4769–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.00721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu J, Ustach C, Kim H-RC. Platelet-derived growth factor signaling and human cancer. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;36:49–59. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2003.36.1.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georege D. Targeting PDGF receptors in cancer-rationales and proof of concept clinical trials. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;532:141–51. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0081-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matei D, Emerson RE, Lai YC, et al. Autocrine activation of PDGFRalpha promotes the progression of ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:2060–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao R, Bjorndahl MA, Religa P, et al. PDGF-BB induces intratumoral lymphangiogenesis and promotes lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:333–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nister M, Claesson-Welsh L, Eriksson A, Heldin CH, Westermark B. Differential expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptors in human malignant glioma cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16755–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chopra A, Brown KM, Rood BR, Packer RJ, Macdonald TJ. The use of gene expression analysis to gain insights into signaling mechanisms of metastatic medulloblastoma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003;39:68–74. doi: 10.1159/000071317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chilton-Macneill S, Ho M, Hawkins C, Gassas A, Zielenska M, Baruchel S. C-kit expression and mutational analysis in medulloblastoma. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7:493–8. doi: 10.1007/s10024-004-1116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matei D, Chang D, Meei-Huey J. Imatinib Mesylate (Imatinib) Inhibits Ovarian Cancer Cell Growth through a Mechanism Dependent on Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor and Akt Inactivation. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:681–690. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0754-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilic T, Alberta JA, Zdunek PR, et al. Intracranial inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor-mediated glioblastoma cell growth by an orally active kinase inhibitor of the 2-phenylaminopyridine class. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5143–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernardi RJ, Lowery AR, Thompson PA, Blaney SM, West JL. Immunonanoshells for targeted photothermal ablation in meduloblastoma and glioma: an in vitro evaluation using human cell lines. J Neurooncol. 2008;86:165–72. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonald TJ, Tabrizi P, Shimada H, Zlokovic BV, Laug WE. Detection of brain tumor invasion and micrometastasis in vivo by expression of enhanced green fluorescenr protein. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:1437–42. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199812000-00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito Y, Haendeler J, Hojo Y, Yamamoto K, Berk BC. Receptor heterodimerization: essential mechanism for platelet-derived growth factor-induced epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6387–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6387-6394.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stearns D, Chaudhry A, Abel TW, Burger PC, Dang CV, Eberhart CG. c-myc overexpression causes anaplasia in medulloblastoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:673–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Servidei T, Riccardi A, Sanguinetti M, Dominici C, Riccardi R. Increased sensitivity to the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor inhibitor ST1571 in chemoresistant glioma cells is associated with enhanced PDGF-BB-mediated signaling and ST1571-induced Akt activation. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:220–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGary EC, Weber K, Mills L, Doucet M, Lewis V, Lev DC, Fidler IJ, Bar-Eli M. inhibition of platelet-derived growth facor-mediated proliferation of osteosarcoma cells by the novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor ST1571. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3584–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostman A, Heldi CH. PDGF receptors as Targets in Tumour treatment. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;97:247–74. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)97011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomson S, Petty F, Sujka-Kwok I, Epstein D, Haley JD. Kinase switching in mesenchymal-like non-small cell lung cancer lines contributes to EGFR inhibitor resistance through pathway redundancy. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:843–54. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Kim YN, Bertics PJ. Platelet-derived growth factor stimulated migration of murine fibroblasts is associated with epidermal growth factor receptor expression and tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2951–2958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He H, Levitzki A, Zhu HJ, Walker F, Burgess A, Maruta H. Platelet-derived growth factor requires epidermal growth factor receptor to activate p21-activated kinase family kinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26741–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decker SJ, Harris P. Effects of platelet-derived growth factor on phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human skin fibroblast. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9204–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu P, Ying Y, Ko YG, Anderson RG. Localization of platelet-derived growth factor-stimulated phosphorylation cascade to caveolae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10299–303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mineo C, James GL, Smart EJ, Anderson RG. Localization of epidermal growth factor-stimulated Ras/Raf-1 interaction to caveolae membrane. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11930–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geng L, Shinohara ET, Kim D, Tan J, Osusky K, Shyr Y, Hallahan DE. ST1571 (Gleevec) improves tumor growth delay and survival in irradiated mouse models of glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin ME, Robson CD, Kieran MW, Jacks T, Pomeroy SL, Cameron S. Marked regretion of metastatic pilocytic astrocytoma during treatment with imatinib mesylate (STI571, Gleevec): a case report and laboratory investigation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:644–8. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200308000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayawardena S, Sooriabalan D, Indulkar S, Kim HH, Matin A, Maini A. refgretion of grade III astrocytoma during the treatment of CML with imatinib mesyltae. Am J Ther. 2006;13:458–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000208270.57626.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.