Abstract

LMP1 is an intracellular scaffold protein that contains a PDZ domain and three LIM domains. LMP1 has multiple functions including regulating mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) osteogenesis. Gene delivery of LMP1 induces bone formation in vivo in heterotopic and orthotopic sites. However, little is known about the physiological function and gene regulatory mechanisms of LMP1 in MSCs at the molecular level. Periodontal ligament (PDL) cells are a unique progenitor cell population that can differentiate into multiple cell types, including osteoblasts, adipocytes or chondrocytes. This study sought to determine the physiological function and gene regulatory mechanisms of LMP1 in PDL cells at the molecular level. We show that LMP1 is upregulated in early stage of PDL cell osteogenic differentiation. Stable gene knockdown of LMP1 by shRNA inhibits DNA synthesis and corresponding cell proliferation in PDL cells, and further leads to decreased mineralization in vitro. Overexpression of LMP1 increases cell proliferation, and PDZ and ww-interacting domains are not enough to mediate this effect. Further, we found that in PDL cells, LMP1 is a downstream target gene of TGF-β1 that is an early signal critical in preosteoblast proliferation and differentiation. TGF-β1 stimulates PDL cell proliferation, however, this effect is compromised when LMP1 is knocked down. We further identified that the activation of TAK1-JNK/p38 kinase cascade is involved in the LMP1 gene regulation by TGF-β1. We conclude that LMP1 is a downstream gene of TGF-β1, involved in PDL cell proliferation. Our findings advance the understanding of the physiological function of LMP1, and define a regulatory mechanism of LMP1 in PDL progenitor cells and other MSCs.

Keywords: LMP1, periodontal diseases, tissue engineering, signal transduction, TGF-β1

Introduction

Gene transfer of key regulators of osteogenesis for mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represents a promising strategy to regenerate bone. The intracellular protein LMP1 (LIM domain mineralization protein) belongs to the PDLIM protein family, which consists of a PDZ domain in the N-terminus and three LIM domains at the C terminus [1, 2]. Increasing evidence suggests that LMP1 regulates the osteogenesis program in MSCs. For example, overexpression of LMP1 in bone marrow stromal stem cells, calvarial osteoblasts, and dermal fibroblasts initiates osteolineage differentiation in vitro [2-5]. Gene delivery of LMP induces efficient bone formation in vivo in heterotopic (subcutaneous and intramuscular) and orthotopic (spine fusion and bone fracture healing) sites [5-8]. Although the potential application of LMP1 in bone regenerative medicine, the physiological roles of LMP1 in MSCs remain to be established. So far, LMP1 knockout mice still haven't been developed, and LMP1 knockdown in zebrafish is embryonically lethal [9].

TGF-β1 is one of the most abundantly deposited growth factors sequestered in bone matrix [10]. It has multiple functions in osteogenesis, regulating osteoblast precursor proliferation, differentiation and migration [10-13]. It is strongly expressed in proliferating osteoblasts during intramembranous ossification, and is strongly expressed in proliferating chondrocytes during chondrogenesis and endochondral ossification [14]. TGF-β1 knock-out mice display a 30% decrease in tibial length and a reduction in bone mineral content [15]. Recombinant TGF-β1 administration increases bone formation and promotes fracture healing in vivo [10]. TGF-β1 exerts cellular functions and affects gene expression through binding to two transmembrane serine/tyrosine kinase receptors (type I and type II). When the type I receptor is activated, Smad dependent and Smad independent signaling pathways are utilized to mediate the extracellular stimulus to the nucleus. In Smad dependent signaling, Smad2 and Smad3 are phosphorylated by type I receptors, forming a trimeric complex with Smad4, subsequently translocating into the nucleus activating target gene transcription [16, 17]. Besides the Smad dependent pathway, other signaling pathways are used by TGF-β1 including the Erk, JNK and p38 MAPK kinase pathways. [16].

Periodontal ligament (PDL) cells are a unique mesenchymal stem cell population that can differentiate into multiple cell types, such as osteoblasts, adipocytes, and neurons [18, 19]. The PDL cell is a promising cell source for periodontal hard and soft tissue regeneration [20, 21]. This study sought to determine the physiological function and gene regulatory mechanisms of LMP1 in PDL cells proliferation and differentiation. We stably knocked down LMP1 by shRNA. Gene knockdown of LMP1 inhibits cell proliferation and DNA synthesis in PDL cells, and further impairs osteogenic differentiation. Overexpression of LMP1 in PDL cells stimulates proliferation, which is not dependent on its PDZ and ww-interacting domains. We also demonstrate that LMP1 is regulated by TGF-β1 in PDL cells, and LMP1 knockdown inhibits the proliferation effect mediated by TGF-β1. We further identified that the activation of TAK1-JNK/p38 kinase cascade is involved in the LMP1 gene regulation by TGF-β1. Our findings may aid in the better understanding of the role of LMP1 in PDL cells proliferation and differentiation, and for the first time, define a regulatory mechanism of LMP1 at molecular level.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The isolation of human periodontal ligament (PDL) cells for these studies was approved by the University of Michigan Health Sciences Institutional Review Board. PDL cells were obtained from extracted third molar or premolar teeth of healthy patients and cultured in 100 mm tissue culture dishes in a DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin [18]. PDL cells from 5 patients (Age range 20-50 years) were pooled and used at passages 2 to 6.

Growth factor and kinase inhibitor treatment

Confluent cultures of the above cells were brought to a stage of quiescence by rinsing the monolayers with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and maintained in serum-free DMEM medium for 24 h prior to treatment. Recombinant human TGF-β1 was reconstituted and used according to the manufacturer's directions (R&D, Minneapolis, MN)). For kinase inhibition experiments, different kinase inhibitors were suspended in DMSO and added to cells 1 h before TGF-β1 treatment. Cycloheximide and SB-431542 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO), while PD98059, SB203580, and SP600125 were acquired from A.G Scientific Inc. (San Diego, CA).

Short Hairpin RNAs (shRNA) and Retroviral Infection and Constructs

Retrovirus-based shRNA knockdown system (pSIREN-RetroQ vector, from Clontech (Mountain view, CA) was utilized to stably knock down endogenous LMP1 expression. Target sequences were selected with software available on the Dharmacon web sites. Oligonucleotides synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) were annealed and subcloned into retroviral vectors at EcoRI and BamHI sites. The two target sequences to LMP1 identified were: si1: 5′-gtttgagtttgctgtgaagtt-3′ and si2: 5′-gcaagagccgagataaagcca-3′. Non-target scramble shRNA sequence is: 5′-aaaaccgacggctatctct-3′. shRNA expression vectors were delivered into PDL cells using retroviral transduction according to the manufacturers instructions. Briefly, PDL cells were transfected by retrovirus twice over 36 h, with a 12 h interval between infections. Next, puromycin (1μg/ml) was added for 3 d. Resistant clones were pooled together for subsequent experiments. At least 6 independent transfections had been performed and the efficiency and specificity of suppression by shRNAs were evaluated with analyses of protein and/or RNA levels as indicated.

LMP1 gene overexpression in PDL cells

Full length LMP1 gene was cloned from MG63 cells by RT-PCR, then was inserted into retrovirus vector pQC-XIN (Clotech, Mountain view, CA). A truncated form without any LIM domain was generated by PCR. After that, retrovirus production and transfection was performed following the similar protocol, and PDL cells were selected by G418 for 10 d.

[methyl-3H]thymidine incorporation assay

PDL cells with stable shRNA expression were seeded in 12-well-plates with 1×104 cells per well. The next day, medium was changed to serum-free DMEM. After 24 h, 2 × 105 cpm (counts per minute) [methyl-3H]thymidine were added to each well. At day 5, the medium was removed and each well was washed twice with cold PBS. The DNA in each well was precipitated with 5% cold trichloroacetic acid at for 2 h 4°C, solubilized with 1% SDS solution for 2 h at 55 °C, followed by measurement of [methyl-3H]thymidine radioactivity in the solution via a scintillation counter (Wallac 1410, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Flow cytometry

3×104 PDL cells cultured on 10cm dishes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, trypsinized, and fixed in cold 70% ethanol for 0.5 h. Ethanol was removed by centrifugation, and the pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 50 μg/ml propidium iodide and RNAse A (10 ug/ml) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C before FACS analysis.

Cell Lysates and Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). SDS-PAGE gels were run and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). After blotting, the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies and appropriate secondary antibodies (anti mouse IgG or anti rabbit IgG, Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 1 h. The membranes were washed and visualized by an ECL chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham). Monoclonal antibody for LMP1 (1:1000) was obtained from Abcam and monoclonal antibody for alpha-tubulin (1:1000) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

RNAi

For PDL cells or hBMSCs RNAi experiments, cells were seeded in 6-well-plates at 2×105 cells per well, and transfected with 100 nM siRNA for 72 h in serum-free and antibiotic-free DMEM. Next, media were changed and cells were stimulated with or without TGF-β1. siGENOME SMARTpool siRNA targeting Smad2, Smad4 and TAK1, and scramble control siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA samples were extracted with RNAeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Maryland) according to the manufacture's instructions. 1 ug RNA was subjected to reverse transcription in a 50μl RT reaction using TaqMan Reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA). cDNA was generated using random hexamer primers and oligo-T primers with 2:1 ratio). For quantitative real-time PCR, the generated cDNA was analyzed, in triplicate, with the Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in the ABI7500 Sequence Detection System. The results were normalized with 18s transcript. The primers and probes were ordered from Applied Biosystem. The probe sequences were: 18S: Hs99999901_s1, TCCATTGGAGGGCAAGTCTGGTGCC; LMP1: Hs01103928_g1, CAAACCGCAGAAGGCCTCCGCCCCC; Smad4, Hs00232068_m1, GGCTTCCACAAGTCAGCCTGCCAGT; Smad2: Hs00183425_m1, TGGACACAGGCTCTCCAGCAGAACT.

Determination of cell number by crystal violet staining

3×103/cm2 PDL cells were seeded in 12-well plates in triplicate with osteogenic induction media. Media were changed every 3 d. Two weeks later, the cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol for 10 minutes. After PBS washing, 0.5% crystal violet solution was added for 10 minutes. Crystal violet was removed and the plates were washed carefully with water 5 times. Photographs were taken using a Nikon digital camera. For crystal violet quantification, Sorenson's buffer (0.1 M sodium citrate, 50% ethanol, 50% H2O) was used to extract the dye and further measured using a spectrometer (Beckman Coulter, Mason, MI) at A540. The optical density readout is positively correlated to cell numbers.

In vitro mineralization assay

PDL cells with stably expressed shRNAs were seeded in 6-well plates in triplicate at the density of 3×103/cm2. In order to induce PDL cells to mineralize, 50 ug/ml ascorbic acid, 5 mM beta-glycerol phosphate, and 10-8M dexamethasone were added to the medium for 2-3 weeks. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining was performed as previous described [22]. Matrix mineralization was evaluated by alizarin red staining and von kossa staining.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD. The significance of the differences was determined by using the two-tailed Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA. For each figure, representative results from 2-3 repeated independent experiments were shown.

Results

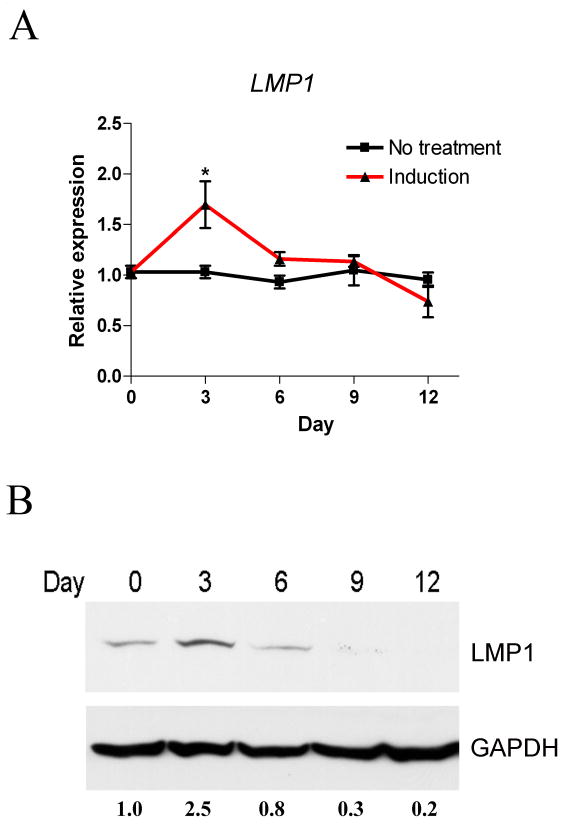

LMP1 is upregulated in the early stage of osteogenic differentiation of PDL cells

PDL cells are a mixed cell population from the tooth-supporting apparatus. It is well established that these cells can differentiate to multiple cell types [18], and we also confirmed that PDL cells from different patients can differentiate to osteoblasts and adipocytes. We next analyzed the gene expression of LMP1 during osteogenic differentiation. As shown in Fig 1A, LMP1 expression is upregulated at 3 d and decreases at later time points. The same pattern was seen at protein level as well (Fig. 1B). This result reveals that LMP1 is involved in the early stage of osteogenic differentiation of PDL cells.

Fig. 1. LMP1 is upregulated at early stage of osteogenesis in PDL cells.

Primary PDL cells were induced for osteogenic differentiation. (A) RT-qPCR was used to evaluate LMP1 gene expression. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown. **, p<0.01; *, p<0.05 vs. non-induced control. (n=3 per group) (B) The LMP1 protein expression is shown by Western Blot. Relative expression ratios after normalization to GAPDH are shown at the bottom.

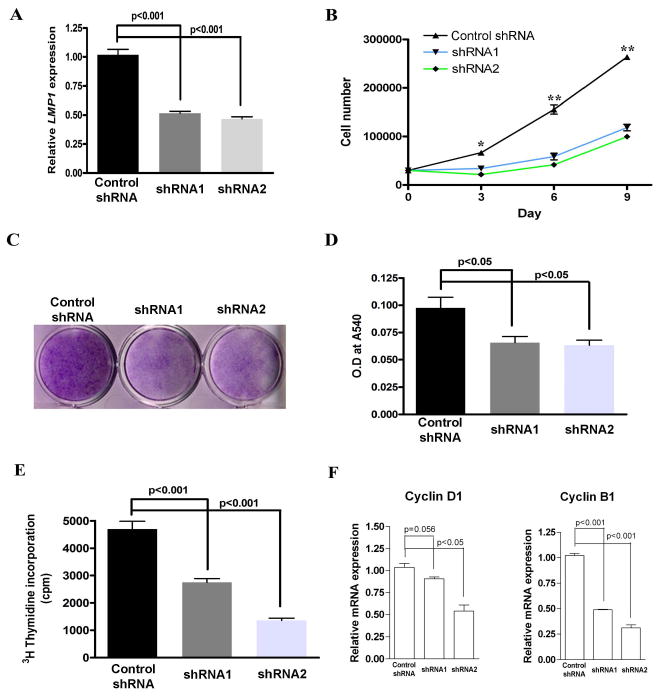

shRNA-mediated silencing of LMP1 impairs PDL cell proliferation

In order to better understand the function of LMP1 in PDL cells, we used RNAi technology to knock down LMP1 gene expression in vitro. Two double-stranded shRNAs targeting LMP1 and a scrambled shRNA were designed and cloned into a retroviral system. After retrovirus infection and puromycin selection, resistant clones were pooled. LMP1 expression was verified at mRNA (Fig. 2A) and protein (Suppl. Fig. 1A) levels. LMP1 knockdown of PDL cells demonstrated lower proliferation rates when compared to controls. When we seeded the same number of cells in 12-well-plates and induced them towards osteolineage differentiation, LMP1 knockdown cells demonstrated a slower proliferation rate compared to control (Fig. 2B). At 10 d, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet staining and less staining was found in knockdown cells (Fig.2 C, D). Consistent with this observation, LMP1 knockdown in PDL cells inhibited DNA synthesis which was shown by 3H methyl thymidine incorporation assay (Fig. 2E). Since this effect can also be explained by the increase of apoptotic cells while LMP1 was knocked down, we further tested the expression of an apoptosis marker Caspase-3. Caspase-3 is a critical driver of both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis, as it is responsible for the proteolytic cleavage of many key factors involved in apoptosis [23]. Activation of caspase-3 requires proteolytic processing of its inactive zymogen into activated p17 and p12 fragments [23]. There is no significant increase of cleaved caspase-3, which indicates that the LMP1 knockdown effect may be related to impaired proliferation and not apoptosis (Suppl. Fig. 1B). Further, by RT-qPCR, we confirmed that LMP1 knockdown resulted in less expression of Cyclin D1 and Cyclin B1 compared to controls (Fig. 2F). FACS analysis further showed that a greater degree of LMP1 knockdown of cells were blocked at the G1 phase compared to scramble control cells (Table 1). Taken together, knockdown of LMP1 expression in PDL cells appears to impair cell proliferation.

Fig. 2. LMP1 is required for PDL cell proliferation.

Two double-stranded shRNAs targeting LMP1 and a scramble shRNA were designed and cloned into a retroviral system. After retrovirus infection and puromycin selection, all the survival cells were pooled. (A) LMP1 mRNA expression was evaluated by RT-qPCR.(B) LMP1 stably knocked down and control PDL cells were seeded in 6-well-plates at low density (3× 103/cm2). Osteogenic media were added to the cells, and media were changed every 3-4 days. At day 3, 6, and 9, cells were harvested and counted by hemocytometry, n=6 per group. (C) At day 10, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. (D) Subsequently, the crystal violet staining was washed and quantified. The optical density readout which correlates to cell numbers are shown. (E) LMP1 stably knocked down and control PDL cells were seeded in 12-well-plate at 3 × 103/cm2 and cultured in osteogenic induction media. 3H methyl thymidine was added after overnight attachment. At 5 d, the DNA was harvested and the 3H methyl thymidine incorporation was measured by scintillation counter. (n=4 per group). (F) PDL cells were cultured in 6-well-plates in serum free medium. 10% FBS was added, and RT-qPCR was used to examine the expression of Cyclin D1 and Cyclin B1 (n=3 per group).

Table 1.

FACS analysis for cell cycle of PDL cells following LMP1 gene knockdown

| G1 | S | G2/M | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control shRNA | 36.17 ± 1.41a,b | 45.28 ± 1.37a,b | 18.54 ± 0.75a,b |

| shRNA 1 | 58.77 ± 1.16 | 30.07 ± 1.96 | 11.15 ± 0.89 |

| shRNA 2 | 44.24 ± 3.51 | 28.55 ± 1.80 | 27.02 ± 2.24 |

PDL cells were cultured in 10 cm petri dishes in serum-free medium overnight. 10% FBS was added for 24h Cells were fixed and stained by PI, analyzing by FACS. n=4 per group.

p<0.01, compared to -shRNA 1

p<0.01, compared to -shRNA 2

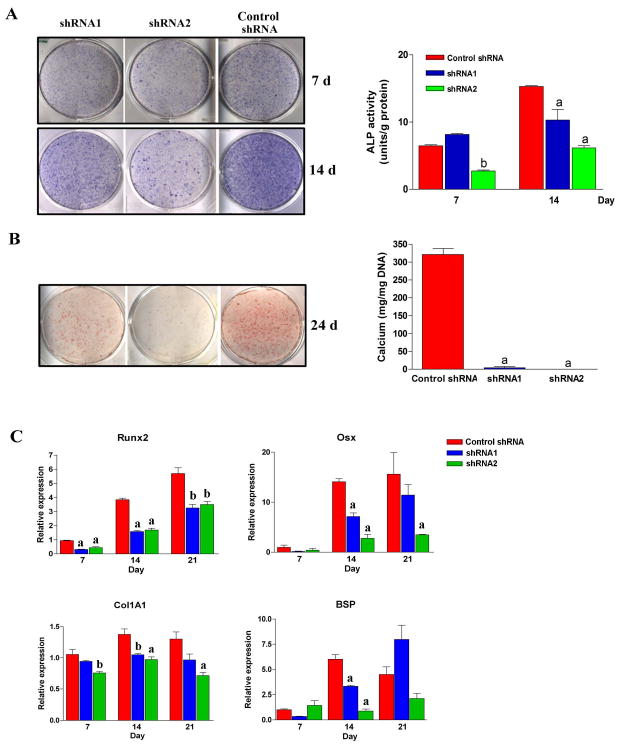

LMP1 silencing delays osteogenic differentiation

We further determined whether gene knockdown of LMP1 affects osteogenic differentiation in PDL cells. Control shRNA showed similar levels of ALP staining and mineralization capability when compared to non-treatment controls (Suppl. Fig. 2). However, less ALP positive cells were seen when LMP1 was stably knocked down by shRNA, and the ALP activity was lower in knockdown cells (Fig. 3A). Consistent with this finding, less mineralized nodules were observed in LMP1 knockdown PDL cells at the late stage of PDL osteogenic differentiation, which was shown by Alizarin Red staining and extracellular measurement (Fig. 3B). We further used RT-qPCR to examine several gene markers involved in PDL differentiation. We found that LMP1 knockdown of PDL cells demonstrated delayed expression of Runx2 and Osterix (Fig. 3C). Collagen1A1 (Col1A1) and Bone sialoprotein (BSP) tended to decrease in LMP1 knockdown cells as well. These results suggest that LMP1 knockdown retards the early osteogenic differentiation of PDL cells in vitro.

Fig. 3. LMP1 silencing decreases osteogenic differentiation in PDL cells. LMP1.

stably knocked down and control PDL cells were seeded in 12-well-plates at low density (3 × 103/cm2). Osteogenic medium was added to the cells, and media were changed every 3-4 days. (A) At indicated time points, ALP activity was measured by ALP staining (left panel), and quantified assay (right panel). (B) Mineralization was assessed by Alizarin Red staining (left), and extracellular calcium concentration was quantified (right). (C) RT-qPCR was performed at d 7, 14, and 21 to evaluate the gene expression of several gene markers (C). a: p<0.01 compared to scramble shRNA in the same time point; b: p<0.05 compared to scramble shRNA in the same time point. n=3 per group.

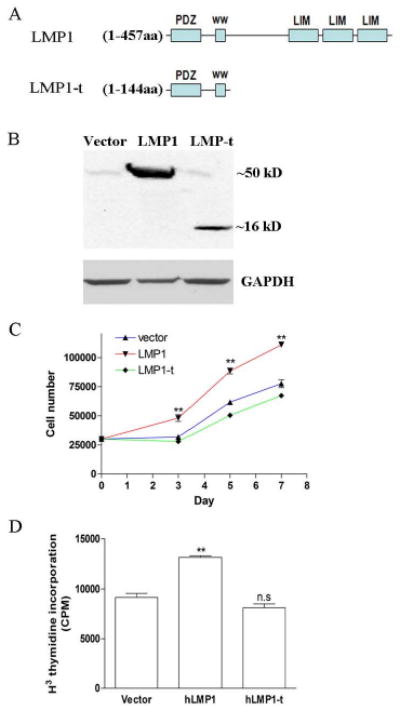

PDZ and ww-interacting domains are not sufficient to stimulate cell proliferation

Our results suggest that LMP1 is required for PDL cell proliferation. To examine whether LMP1 transgene can enhance PDL cell proliferation, we stably overexpressed LMP1 in PDL cells using a retroviral system. We also established stable PDL cell lines expressing a truncated form of LMP1 only containing the first 144 amino acid residues, which consists of PDZ domain and ww-interacting motifs, but not any LIM domains (Fig. 4A and Suppl. Fig. 3). The antibody we used can recognize the N-terminus of LMP1, which made it possible to detect both forms in Western blot (Fig. 4B). The full length LMP1 is about 50 kD, and the truncated form in about 16kD. As shown in Fig 4C, expression of the full length LMP1 significantly promoted PDL cell proliferation, however, the truncated form had limited effect. Significant cell death was not observed during cell culture. Consistent with this finding, there was no significant increase in the cleaved active fragments of caspase-3, for both control and LMP-t PDL cells (Suppl. Fig. 4). By 3H methyl thymidine incorporation assay we further showed that DNA synthesis is upregulated in LMP1 overexpression PDL cells (Fig. 4D). Therefore, our result suggests that PDZ and ww-interacting domains are not sufficient to stimulate the mitotic effect. This is finding is consistent with the work of Durick et al reporting that LMP1 mediates the mitogenic signaling in mouse fibroblasts [24].

Fig. 4. PDZ and ww-interacting domains are not enough to induce PDL cell proliferation.

Full length LMP1 cDNA and a truncated form without any LIM domain were constructed into retroviral expression vector. PDL cells were transfected by retrovirus and selected by G418 for 10 days. Survived cells were pooled for the following experiments. Stable cell lines overexpressing LMP1 and LMP1-t were established in PDL cells from two different individuals. Representative data from 1 patient were shown here. (A) Truncated LMP1 only contains the first 144 aa including PDZ and ww interacting domains. (B) Endogenous and exogenous LMP1 proteins were detected by western blot. This antibody can detect the truncated form LMP1-t as well. (C) PDL cells were seeded in 6-well-plates at low density (3 × 103/cm2). Cells were harvested by trypsin and counted using hemocytometry, n=6 per group. (D) PDL cells were seeded in 6-well-plate at 3 × 103/cm2 and 3H methyl thymidine was added. At 5 d, the DNA was harvested and the 3H methyl thymidine incorporation was measured by scintillation counter. (n=4 per group)

LMP1 gene and protein expression is regulated by TGF-β1

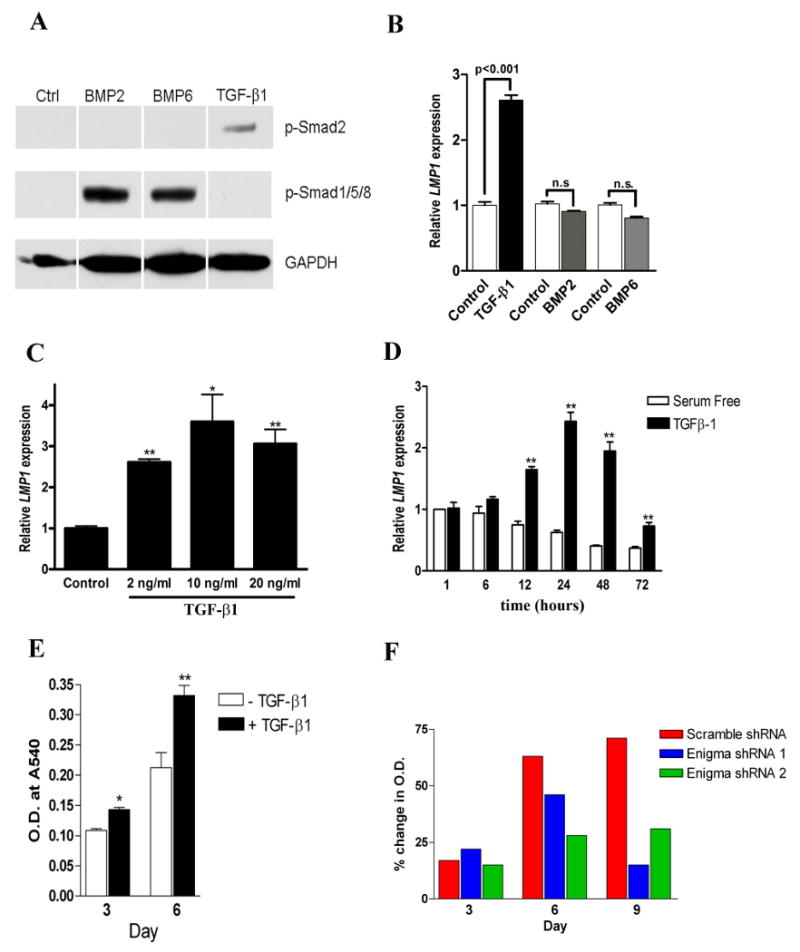

It has not been clear about how LMP1 gene expression is regulated at osteoblast progenitors. Based on its role in the early stage of PDL progenitor cell osteogenesis, we hypothesized that LMP1 may be regulated by early signals critical to proliferation and differentiation, such as TGF-β1, BMP2, BMP6, and PDGF-BB. To test our hypothesis, PDL cells were treated by different growth factors and we first confirmed that all the growth factors can activate downstream signaling molecules, for instance, smad1/5/8 and smad2 (Fig. 5A). Consequently, we found that TGF-β1 but not BMP-2/6/ stimulated LMP1 gene expression (Fig. 5B). PDGF-BB also stimulated LMP1 expression, however, the effect is very limited compared to TGF-β1 (data not shown). We further confirmed that TGF-β1-induced LMP1 expression occurs in other osteoblast progenitor cells as well, such as hBMSCs and MG63 cells, even with much stronger effect (Suppl. Fig. 5). Of the doses that we tested, 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 induced consistent high level LMP1 gene expression (Fig. 5C). We next examined the temporal profile of LMP1 in response to TGF-β1 in PDL cells. LMP1 expression was induced by 6 h following TGF-β1 treatment, peaking at 24 h, and slowly returned to basal levels by 72 h (Fig. 5D). Using Western blotting, we further found that LMP1 protein was increased at 24 h post-treatment in PDL cells (data not shown). These results indicate that LMP1 is regulated by TGF-β1 in PDL cells.

Fig. 5. LMP1 knockdown attenuates the TGF-β1 effect on PDL cells proliferation.

(A) PDL cells were stimulated with TGF-β1 (2ng/ml), BMP2 (100ng/ml), or BMP6 (100ng/ml). phosphorylated-Smad1/5/8 and phosphorylated-Smad2 was examined by Western blot. (B) RNA was extracted after 24 h and RT-qPCR was used to evaluate LMP1 gene expression. LMP1 mRNA expression values was normalized to 18s RNA relative to that of serum-free controls. (C) After incubation in serum-free medium for 24 hours, human PDL cells were stimulated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml, 10 ng/ml, and 20ng/ml). 24 hours later, RNA was extracted and RT-qPCR was use to measure the expression level of LMP1. **: P<0.01 compared to serum free control; *: P<0.05 compared to serum free control. n=3 per group. (D) PDL cells were treated by TGF-β1 at 2 ng/ml. At various time points, LMP1 mRNA expression was measured by RT-qPCR. Open bar: PDL cells in serum free condition without TGF-β1. Closed bar: with TGF-β1. **: p<0.01 compared to serum-free control at the same time point. (E) PDL cells were cultured in DMEM with low serum concentration (2% FBS), and some cells were treated by TGF-β1. At day 3 and day 6, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. The optical density readout which correlates to cell numbers are shown, n=3 per group. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01. (F) LMP1 knockdown PDL cells and control cells were cultured in 6-well-plates in 2% FBS, with/without TGF-β1. At day 3, 6, 9, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. The data showed the percentage change of crystal violet measurement between no TGF-β1 and TGF-β1 treatment (n=3 per group).

LMP1 knockdown attenuates the TGF-β1 effect on PDL cell proliferation

The effect of TGF-β1 on PDL cell proliferation appears to depend on TGF-β1 dose and cellular context. In the PDL cells we used, TGF-β1 stimulus significantly induced cell proliferation (Fig. 5E) and DNA synthesis (data not shown). Next, we evaluated whether LMP1 is involved in the TGF-β1 effect on PDL cells proliferation. LMP1 knockdown of expression by shRNA in PDL cell resulted in a blockage of TGF-β1 dependent proliferation (Fig. 5F). This further suggests that LMP1 may be involved in the proliferative effect of TGF-β1 in the early stage of PDL differentiation.

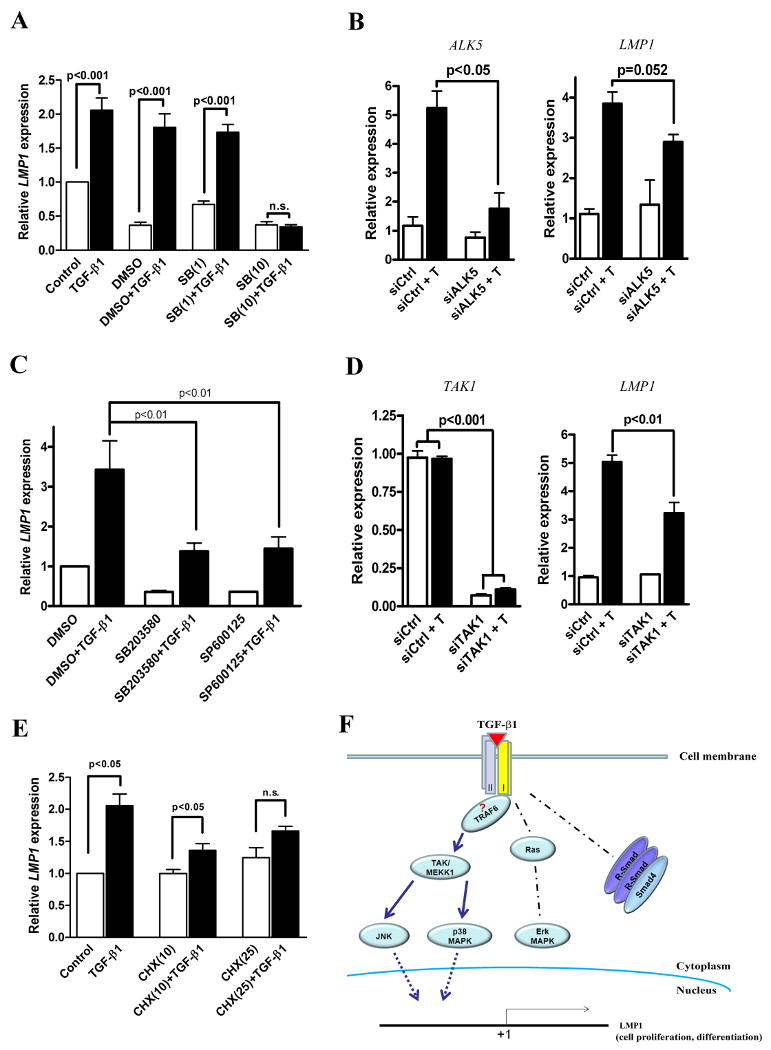

TGF-β1 induction of LMP1 is specifically mediated by TGF-βI receptors

TGFβ signaling is initiated by ligand binding leading to the formation of receptor complexes, which comprises type II and type I serine/threonine kinase receptors. The type II receptor phosphorylates and activates the type I receptor which further phosphorylates various Smad molecules. Seven known type I receptors, also called activin receptor-like kinases (ALKs), have been divided into two categories: ALK-4, -5, and -7, corresponding to the TGFβ/Activin/Nodal branch through phosphorylating Smad-2 and -3, while ALK-1, -2, -3, and -6 corresponds to the BMP/GDF branch and mediate Smad-1, -5, and -8 phosphorylation. SB-431542 is a selective inhibitor to ALK-4, 5, and 7, without affecting ALK-1, -2, -3, and -6 and corresponding to BMP signaling. SB-431245 suppressed TGF-β1 induced LMP1 expression in PDL (Fig. 6A). These results suggest that TGF-β1 induces LMP1 expression through TGF-βRI activation. In order to rule out the non-specific effect of SB-431245, we used siRNA to knockdown ALK5 expression in PDL cells. Consistent with this was ALK5 knockdown compromised the LMP1 expression stimulated by TGF-β1 (Fig. 6B), although this effect couldn't be completely abolished. This result may be due to the redundancy of other TGF-βRI such as ALK4 and ALK7. It has been reported that SaOS2 cells possess type I but no type II TGFβ receptors on the cell surface [25]. This led to the very limited effects by TGF-β1 on cell proliferation and proteoglycan synthesis of SaOS2 cells. We found that LMP1 is not induced by TGF-β1 in SaOS2 cells that further supports that the TGF-β1 effect on LMP1 expression is specifically through TGF-βI receptors.

Fig. 6. TAK1-JNK/p38 cascade is involved in TGF-β1 induction of LMP1.

(A) Confluent PDL cells were free for serum for 24 h. Prior to adding TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml), PDL cells were pretreated by SB431542 for 1 h. 24 h after TGF-β1 treatment, LMP1 gene expression was measured by RT-qPCR, normalized to 18s mRNA, and given relative to that of serum-free control. Control: serum-free. SB(1): SB431532 in DMSO, 1μM. SB(10): SB431532 in DMSO, 10μM. n.s.: no significant difference. (B) ALK5 siRNA was transfected into PDL cells for 72 h in serum-free media, followed by TGF-β1 stimulation. At 24 hours, RNA was extracted and qRT-PCR was used to examine the expression of ALK5 and LMP1. ALK5 knockdown compromised the effect of TGF-β1 on LMP1 gene expression. (C) Before adding TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml), PDL cells were pretreated by MAPK kinase inhibitors for 2 h. 24 h after TGF-β1 treatment, LMP1 gene expression was measured by RT-qPCR. DMSO was used as the solvent for all the inhibitors. SB203580: p38 inhibitor, 25μM. SP600125: JNK inhibitor, 25μM. (D) PDL cells were transiently transfected with 100nM siRNA (targeting TAK1 or scramble control) for 72 h, in serum-free and antibiotics-free DMEM. After treatment, media were changed (serum and antibiotics-free), and TGF-β1 was added. After 24 h, RT-qPCR was performed to measure gene expression. Left panel: TAK1 gene expression. Right panel: LMP1 gene expression. siCtrl: scramble siRNA; siCtrl + T: scramble siRNA and TGF-β1 treatment; siTAK1: TAK1 siRNA; siTAK1 + T: TAK1 siRNA and TGF-β1 treatment. (E) Confluent PDL cells were cultured in serum-free media for 24 h. Before adding TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml), PDL cells were pretreated by cycloheximide (CHX) for 2 h. 24 h after TGF-β1 treatment, LMP1 gene expression was measured by RT-qPCR, normalized to 18S mRNA, and given relative to that of serum free control. CHX(10): cycloheximide 10μM; CHX(25): cycloheximide 25μM. (F) Schematic overview of the regulation of LMP1 gene expression by TGF-β1. (n=3 per group in each experiment).

TAK1-JNK/p38 cascade is involved in TGF-β1 induction of LMP1

To further identify the signaling pathway that TGF-β1 uses to stimulate LMP1 gene expression, we first knocked down the canonical Smad signaling by siRNA. Unexpectedly, both Smad4 and Smad2 knockdown did not affect the up-regulation of LMP1 after TGF-β1 stimulation in PDL cells (Suppl. Fig. 6). It is known that activated TGFβ receptors also trigger a Smad independent signaling pathway such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade [16, 26-28]. ERK, JNK and p38 are three members of MAPK signaling. U0126 is a MAP kinase inhibitor selectively blocking the ERK1/2 phosphorylation but not JNK and p38. However, U0126 pretreatment failed to block TGF-β1-induced LMP1 gene expression (Suppl. Fig. 7). Consistent with it, another Ras-Erk signaling inhibitor PD98059 had very limited effect on TGF-β1-induced LMP1 gene expression (data not shown). However, when we pre-treated PDL cells with SB203580 (p38 kinase inhibitor) and SP600125 (JNK kinase inhibitor), the LMP1 gene expression stimulated by TGF-β1 was significantly blocked (Fig. 6C). To further confirm the roles of JNK and p38 in LMP1 gene expression, we used siRNA to knock down their upstream regulator TAK1 (TGF-β-activated kinase 1). When TGF-βRI is activated, TAK1 phosphorylates JNK and p38, but not Erk1/2 [29]. After siRNA transfection, the expression of TAK1 was successfully knocked down ∼90%. The gene knockdown of TAK1 inhibits the LMP1 gene expression ∼50% (Fig. 6D). Taken together, non-canonical pathways, particularly TAK1-JNK/p38 cascade, play an important role in TGF-β1-induced LMP1 upregulation. The phosphorylation of JNK and p38 kinase regulates downstream target genes indirectly through activating AP-1 or ATF2 transcription and translation. Using bioinformatics analysis, it was identified that there is an AP-1 binding site in the LMP1 promoter, which suggested that TGF-β1 induction of LMP1 requires de novo protein synthesis [30]. To test this, we utilized Cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit protein synthesis. Pre-treatment with CHX 1 h prior to addition of TGF-β1 effectively blocked LMP1 mRNA induction in PDL cells (Fig. 6E). This is consistent with the observation that LMP1 is not an early response gene of TGF-β1, and LMP1 mRNA begins to increase several hours after TGF-β1 treatment. Taken together, the activation of TAK1-JNK/p38 kinase cascade is used by TGF-β1 to regulate LMP1 gene expression.

Discussion

Although it has been reported that LMP1 play a role in osteoblast differentiation [4, 31, 32], its physiological function remains unclear. Because LMP1 is highly expressed in periodontal ligament tissue and it is up-regulated at early stages of osteogenic differentiation in PDL cells, we further explored the possible function of LMP1 in PDL cells. By stable expression of two shRNAs in PDL cells, we observed that the proliferation and DNA synthesis capability decreased in LMP1 knockdown PDL cells compared to non-target shRNA control. LMP1 knockdown appears to lead to longer G1 phase in PDL cells. On the other hand, using a “gain-of-function” strategy, we showed that LMP1 overexpression significantly promotes PDL cell proliferation. Consistent with this finding, Yoon et al showed that LMP1 transfection induced mild but significant increased in DNA synthesis in intervertebral disc annulus cells [33]. These results suggest that LMP1 is necessary and sufficient for PDL cell proliferation.

It is not clear how LMP1 participates in cell proliferation. By the truncated mutation experiment, we found that PDZ and ww-interacting domains are not enough to induce the mitogenic effect of LMP1. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that LMP1 exerts its function as a scaffold protein that mediates mitogenic signaling activated by growth factors. Durick et al showed that LMP1 mediates the mitogenic signaling by Ret/ptc2 in mouse 10T1/2 fibroblasts. LMP1 binds to Ret/ptc2 via its second LIM domain and functions as an adaptor protein, with the PDZ domain of LMP1 anchoring the LMP1-Ret/ptc2 complex to the cell periphery [1, 24]. On the other side, overexpression of a truncated form of LMP1 without LIM domains inhibited the mitogenic effect of Ret/ptc2 [24]. In future study, it will be important to identify the binding partners of LMP1 in order to characterize its mechanism in PDL cell proliferation.

Osteogenesis is a complex process involving cell proliferation, subsequent nodule formation and mineralization. Our data showed that LMP1 gene knockdown impairs PDL proliferation, and consequently the mineralization was delayed. This is consistent with the observation of Boden and co-workers [2]. Contrastingly, when LMP1 was stably overexpressed in PDL cells, it did not promote mineralization nodule formation in vitro and bone formation in vivo (data not shown). We found that constitutional expression of LMP1 tends to inhibit mineralization in PDL cells. Future studies will need to better determine the role of LMP1 in affecting PDL cell-mediated mineralization in vivo. One possible explanation is that LMP1-overexpressed PDL cells tend exist in a proliferative state, thus delaying the cell's transit into a differentiation state to allow subsequent mineralization of the matrix.

To date, the regulatory mechanism of LMP1 remains “enigmatic”. Because of the up-regulated expression of LMP1 in early stages of MSC osteogenesis and the significant effect of LMP1 in PDL progenitor cell proliferation, we hypothesized that LMP1 is regulated by some of mitogenic growth factors in the early signals of osteogenesis. It is widely accepted that TGF-β1 stimulates MSC proliferation during endochondral ossification and the early phase of bone fracture healing [10]. In this study we identified that LMP1 is a downstream gene of TGF-β1 in human MSCs including PDL cells, bone marrow MSCs and the preosteoblast cell line, MG63 (Fig. 5, Suppl. Fig. 5). It is worth mentioning that TGF-β1 induces ∼10 fold increase of LMP1 expression in MG63, and it would be interesting to further investigate its biological mechanisms. Boden et al. reported that LMP1 is regulated by BMP6 in rat calvarial osteoblasts [2], however, none of the BMPs that we tested were able to stimulate LMP1 expression in PDL cells and hBMSCs (data not shown). Although LMP1 may indeed respond to different TGFβ superfamily members in different species, our data suggests that TGF-β1, but not BMPs, is the main regulator of LMP1 gene expression in human preosteoblastic cells. In addition to TGF-β1, PDGF-BB is a mitogenic growth factor involved in periodontium development and regeneration [19, 34, 35]. The fact that LMP1 is regulated by TGF-β1 and PDGF-BB, but not other BMPs, also supports our hypothesis that LMP1 is a mitogenic player in PDL cells.

Our studies demonstrate a signaling pathway in which TGF-β1 regulates LMP1 gene expression. We found that it appears that canonical Smad signaling is not involved in TGF-β1-induced LMP1 expression, however, TAK1-JNK/p38 cascade mediates the TGF-β1 effect. Here, our data suggest a possible model of TGF-β1-induced LMP1 gene regulation (Fig. 6F). TGF-β1 ligand binding activates type II and I receptors, and then stimulates TAK1 activation that further phosphorylates JNK and p38 MAPK kinases. The phosphorylation of JNK and p38 kinase will activate LMP1 gene transcription through AP-1 or ATF2 activation. TGF-β1-induced LMP1 expression is independent of Ras-Erk signaling and Smad signaling pathways. Bioinformatics finding also supports this model since there is an AP-1 binding site in the LMP1 promoter, whereas no Smad binding site is found [30]. In this model, TRAP6 may be the player mediating the type I TGF-β receptors and TAK1 because recently it has been shown that TRAP6 is specifically required for the Smad-independent activation of JNK and p38 via the physical interaction between its carboxyl TRAF homology domain with type I TGF-β receptors [36, 37]. Of note, other TGF-β1 downstream genes have been found to be regulated by Smad independent, JNK and/or p38 dependent, pathways. For example, TGF-β1 induces fibronectin synthesis through JNK dependent but a Smad4 independent pathway [38]; p38 signaling is used by TGF-β1 to induce connexin43 gene expression in normal murine mammary gland epithelial cells and these effects are Smad-independent [39]. However, it is still plausible that other signaling pathways, such as RhoA and PP2A, are involved in the LMP1 gene regulation.

In addition to LMP1's role in osteogenesis, it might be involved in the adipocyte differentiation as well. It has been shown that LMP1 mRNA expression increases in adipose tissue of diabetic obese patients. LMP can bind to insulin receptor, and it also interacts with adaptor protein with PH and SH2 domains (APS) to control insulin-induced actin cytoskeleton remodeling and glucose transporter 4 translocation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. In the future it will be interesting to explore the function of LMP1 in adiopogensis.

We conclude that LMP1 is required for PDL cell proliferation and osteolineage differentiation. With the limits of the lack of an in vivo LMP1 knockout model, our findings suggest a possible physiological function of LMP1, and define a regulatory mechanism of LMP1 in PDL progenitor cells and other MSCs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Reinhard Gruber, Mallory A. Mitchell, Min Oh, Michelle E. Webb, and Kemal Ustun for technical support.

This work is funded by NIH/NIDCR DE13397 and ITI Foundation to W.V.G.

Z.L. is also funded by Predoctoral Fellowship from Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies, University of Michigan. V.P.N. was funded by FAPESP.

Abbreviations

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor β-1

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PDL

periodontal ligament

- hBMSC

human bone morrow stromal cell

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal Kinase

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Smad2

SMAD family member 2

- Smad4

SMAD family member 4

- CHX

Cycloheximide

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Durick K, Wu RY, Gill GN, Taylor SS. Mitogenic signaling by Ret/ptc2 requires association with enigma via a LIM domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12691–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boden SD, Liu Y, Hair GA, Helms JA, Hu D, Racine M, Nanes MS, Titus L. LMP-1, a LIM-domain protein, mediates BMP-6 effects on bone formation. Endocrinology. 1998;139:5125–34. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boden SD, Titus L, Hair G, Liu Y, Viggeswarapu M, Nanes MS, Baranowski C. Lumbar spine fusion by local gene therapy with a cDNA encoding a novel osteoinductive protein (LMP-1) Spine. 1998;23:2486–92. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Hair GA, Boden SD, Viggeswarapu M, Titus L. Overexpressed LIM mineralization proteins do not require LIM domains to induce bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:406–14. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pola E, Gao W, Zhou Y, Pola R, Lattanzi W, Sfeir C, Gambotto A, Robbins PD. Efficient bone formation by gene transfer of human LIM mineralization protein-3. Gene Ther. 2004;11:683–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minamide A, Boden SD, Viggeswarapu M, Hair GA, Oliver C, Titus L. Mechanism of bone formation with gene transfer of the cDNA encoding for the intracellular protein LMP-1. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1030–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lattanzi W, Parrilla C, Fetoni A, Logroscino G, Straface G, Pecorini G, Stigliano E, Tampieri A, Bedini R, Pecci R, Michetti F, Gambotto A, Robbins PD, Pola E. Ex vivo-transduced autologous skin fibroblasts expressing human Lim mineralization protein-3 efficiently form new bone in animal models. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1330–43. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strohbach CA, Rundle CH, Wergedal JE, Chen ST, Linkhart TA, Lau KH, Strong DD. LMP-1 retroviral gene therapy influences osteoblast differentiation and fracture repair: a preliminary study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;83:202–11. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ott EB, Sakalis PA, Marques IJ, Bagowski CP. Characterization of the Enigma family in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3144–54. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssens K, ten Dijke P, Janssens S, Van Hul W. Transforming growth factor-beta1 to the bone. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:743–74. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanaan RA, Kanaan LA. Transforming growth factor beta1, bone connection. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:RA164–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck LS, Ammann AJ, Aufdemorte TB, Deguzman L, Xu Y, Lee WP, McFatridge LA, Chen TL. In vivo induction of bone by recombinant human transforming growth factor beta 1. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:961–8. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackie EJ, Trechsel U. Stimulation of bone formation in vivo by transforming growth factor-beta: remodeling of woven bone and lack of inhibition by indomethacin. Bone. 1990;11:295–300. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90083-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z, Luyten FP, Lammens J, Dequeker J. Molecular signaling in bone fracture healing and distraction osteogenesis. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:587–95. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiser AG, Zeng QQ, Sato M, Helvering LM, Hirano T, Turner CH. Decreased bone mass and bone elasticity in mice lacking the transforming growth factor-beta1 gene. Bone. 1998;23:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massague J, Gomis RR. The logic of TGFbeta signaling. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2811–20. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J, Young M, Robey PG, Wang CY, Shi S. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet. 2004;364:149–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao JJ, Giannobile WV, Helms JA, Hollister SJ, Krebsbach PH, Longaker MT, Shi S. Craniofacial tissue engineering by stem cells. J Dent Res. 2006;85:966–79. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Zheng Y, Ding G, Fang D, Zhang C, Bartold PM, Gronthos S, Shi S, Wang S. Periodontal ligament stem cell-mediated treatment for periodontitis in miniature swine. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1065–73. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Fang D, Yamaza T, Seo BM, Zhang C, Liu H, Gronthos S, Wang CY, Shi S, Wang S. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PLoS One. 2006;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruber R, Kandler B, Fuerst G, Fischer MB, Watzek G. Porcine sinus mucosa holds cells that respond to bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-6 and BMP-7 with increased osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15:575–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riedl SJ, Salvesen GS. The apoptosome: signalling platform of cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:405–13. doi: 10.1038/nrm2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durick K, Gill GN, Taylor SS. Shc and Enigma are both required for mitogenic signaling by Ret/ptc2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2298–308. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeuchi Y, Fukumoto S, Matsumoto T. Relationship between actions of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta and cell surface expression of its receptors in clonal osteoblastic cells. J Cell Physiol. 1995;162:315–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041620303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MK, Pardoux C, Hall MC, Lee PS, Warburton D, Qing J, Smith SM, Derynck R. TGF-beta activates Erk MAP kinase signalling through direct phosphorylation of ShcA. Embo J. 2007;26:3957–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Feng XH, Derynck R. Smad3 and Smad4 cooperate with c-Jun/c-Fos to mediate TGF-beta-induced transcription. Nature. 1998;394:909–13. doi: 10.1038/29814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Non-Smad TGF-beta signals. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3573–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:128–39. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Viggeswarapu M, Sangadala S, Bargouti M, Titus L, Boden SD. Identification and Analysis of Human LMP Gene Promoter Region. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23 1:382. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barres R, Gonzalez T, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. The interaction between the adaptor protein APS and Enigma is involved in actin organisation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;308:334–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barres R, Gremeaux T, Gual P, Gonzalez T, Gugenheim J, Tran A, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. Enigma interacts with adaptor protein with PH and SH2 domains to control insulin-induced actin cytoskeleton remodeling and glucose transporter 4 translocation. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2864–75. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon ST, Park JS, Kim KS, Li J, Attallah-Wasif ES, Hutton WC, Boden SD. ISSLS prize winner: LMP-1 upregulates intervertebral disc cell production of proteoglycans and BMPs in vitro and in vivo. Spine. 2004;29:2603–11. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146103.94600.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramseier CA, Abramson ZR, Jin Q, Giannobile WV. Gene therapeutics for periodontal regenerative medicine. Dent Clin North Am. 2006;50:245–63. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu Z, Lee CS, Tejeda KM, Giannobile WV. Gene transfer and expression of platelet-derived growth factors modulate periodontal cellular activity. J Dent Res. 2001;80:892–7. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800030901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamashita M, Fatyol K, Jin C, Wang X, Liu Z, Zhang YE. TRAF6 mediates Smad-independent activation of JNK and p38 by TGF-beta. Mol Cell. 2008;31:918–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorrentino A, Thakur N, Grimsby S, Marcusson A, von Bulow V, Schuster N, Zhang S, Heldin CH, Landstrom M. The type I TGF-beta receptor engages TRAF6 to activate TAK1 in a receptor kinase-independent manner. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1199–207. doi: 10.1038/ncb1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hocevar BA, Brown TL, Howe PH. TGF-beta induces fibronectin synthesis through a c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent, Smad4-independent pathway. Embo J. 1999;18:1345–56. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tacheau C, Fontaine J, Loy J, Mauviel A, Verrecchia F. TGF-beta induces connexin43 gene expression in normal murine mammary gland epithelial cells via activation of p38 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:759–68. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.