Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the psychometric properties and preliminary validity of a newly developed 16-item measure to assess maladaptive responses to the stress of being at risk for HIV infection among HIV-negative gay men. The measure consisted of three factors: (1) fatalistic beliefs about maintaining an HIV-negative serostatus; (2) reduced perceived severity of HIV infection due to advances in medical treatment of HIV/AIDS; and (3) negative affective states associated with the risk of HIV infection. A total of 285 HIV-negative gay men at a counseling program in New York City participated in the study. Confirmatory factor analyses supported the three-factor model as an acceptable model fit: NNFI = .91, CFI = .92, GFI = .90, RMSEA = .07. The measure and its subscales obtained in this sample achieved adequate internal consistency coefficients. Construct validity was supported by significant positive associations with internalized homophobia, depression, self-justifications for the last unprotected anal intercourse (UAI), and actual UAI with casual sex partners. Understanding the dynamics of maladaptive responses to the epidemic and intense anxieties elicited by HIV risk among HIV-negative gay men living in a place of high seroprevalence provides useful information to guide psychosocial interventions in the population.

Keywords: fatalistic beliefs, treatment optimism, assessment, gay men, HIV risk

After years of exposure to the HIV/AIDS epidemic and to public health messages about prevention, sexual risk decision making among gay men has become less dependent upon the degree of knowledge or norms about HIV prevention; sexual risk taking is rather an outcome of a constructive process influenced by self-concept and interpersonal, situational, and social contexts, shaped by the prolonged and dynamic HIV epidemic (Adam, Husbands, Murray, & Maxwell, 2005; Harper, 2007; Stall, Hays, Waldo, Ekstrand, & McFarland, 2000; Wolitski, Valdiserri, Denning, & Levine, 2001). If individuals perceive that they are capable of managing an HIV risk situation, one would expect that they would develop a positive adaptive response to the psychosocial stressors that are associated with the epidemic. When HIV risk is perceived as uncontrollable, however, maladaptive responses to the stressor would be more prevalent along with negative affective states (Austenfeld & Stanton, 2004; Gerrard, Gibbons & Bushman, 1996; Folkman, Lazraus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986). Identifying maladaptive responses to the stress of being at risk of HIV infection among gay men is particularly relevant because the availability of Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapies (HAART) has changed the appraisal of sexual risk, and HIV has been in the gay community for prolonged time without the development of a cure or vaccine for HIV/AIDS (Valdiserri, 2004).

Since the onset of the epidemic, psychological research among HIV-positive gay men has examined various cognitive and behavioral responses to stressors caused by HIV illness: self-concept, mental and physical health, management of stigma and discrimination associated with HIV/AIDS and homosexuality, adherence to treatment, and sustaining safer sex (Brown & Vanable, 2008; Kelly, Bimbi, Izienicki, & Parsons, 2009; Halkitis, Gomez, & Wolitski, 2005; Ironson & Hayward, 2008; Mosack et al., 2009; Scott-Sheldon, Kalichman, Carey, & Fielder, 2008). In contrast, relatively fewer empirical studies have addressed HIV infection as a stressor in HIV-negative gay men and its association with sexual identity, mental health, and sexual risk behavior. HIV-negative gay men may respond to this stress by adjusting their norms to fit the challenges associated with safer sex practices or by seeking prevention resources and reducing risk behaviors; while other gay men may respond to HIV risk by subjectively interpreting the risk as “not serious,” or by reframing their experiences and viewing the current epidemic in fatalistic way. The likelihood that gay men develop schemas of fatalistic and optimistic beliefs would increase if gay men perceived HIV risk beyond their coping abilities and the behavioral regulation of condom use too restrictive to sustain (McKirnan, Ostrow, Hope, 1996; Williams, Elwood, & Bowen, 2000).

Despite decades of efforts to disseminate knowledge about the severity of HIV infection and HIV prevention skills, unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) with casual partners and/or HIV status discordant or unknown partners resurged among gay men in the post-HAART era (Wolitski et al., 2001). For the five consecutive years between 2001 and 2006, new HIV diagnoses among MSM in the U.S. have significantly increased, while decreasing rates were reported among other at-risk groups, including injection drug users and high-risk heterosexuals; the increase in HIV cases was much higher for young men who have sex with men (MSM) compared to older MSM (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). The most recent data, especially, estimated that 56,300 new HIV infections occurred in the U.S. in 2006, compared to the previous annual incidence estimates of 40,000 since the early the 1990s; MSM accounted for 53% of all new infections and 74% among men (Hall et al., 2008).

Assessing Maladaptive Reponses to the Stress of HIV Risk

The challenge in current HIV prevention is to understand psychological accounts of sexual risk taking among those who are knowledgeable of HIV prevention and risks, and yet have difficulty sustaining safer sex practices (Elford, 2006; Kippax & Race, 2003). There is a need to develop measures that can assess maladaptive responses to the impact of the epidemic. The explicit assessment of constructs that account for HIV risk as a stressor among HIV-negative gay men should inform the development of effective prevention interventions and research with integrity and specificity. In this measurement study, maladaptive responses are defined as beliefs and attitudes that are oriented away from intention to influence or change the conditions of the stressors, and anxieties as elicited negative affective states in the course of such maladaptive responses (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). As suggested by literature on psychological adaptation and anxiety (Rotenberg & Boucsein, 1993; Wheeler & Lord, 1999), when the “threat of HIV risk” is perceived as pervasive and the prevention norm of “condom use on every sexual occasion” is perceived as a high level of behavioral commitment, anxiety can become either a motivating force that leads HIV-negative gay men to engage in safer sex, or instead may motivate them to implement maladaptive responses that reduce their anxiety and thus leaves them vulnerable to HIV infection.

Several constructs relating to maladaptive responses to HIV risk among gay men have been examined: HAART-related optimistic attitudes toward HIV illness, fatigue with safer sex and prevention messages, and fatalistic beliefs about sustaining preventive behaviors (Valdiserri, 2004). Research has examined the effect of optimistic attitudes toward HIV illness (often called “treatment optimism”) on sexual risk taking and found a positive association with an increase in UAI among MSM regardless of HIV status (for a review see Crepaz, Hart, & Marks, 2004). Studies also noted that “treatment optimism” on its own, however, might not fully explain the underlying complex factors of sexual risk taking among gay men at a population level (Elford, 2004). Treatment optimism might be a result of cognitive dissonance after an event of sexual risk taking, or such attitudes may be developed to reduce anxiety of HIV infection (Crepaz et al., 2004; Huebner, Rebchook, & Kegeles, 2004). Second, there has been discussion about fatigue with preventive behaviors among MSM. Fatigue with safer sex refers to a state of burnout with maintaining safer sex (Ostrow et al., 2002, 2008), and fatigue with HIV prevention, defined as the “attitude that HIV prevention messages, programs, outreach, or counseling services have become tiresome” (Stockmen et al., 2004, p 432). In these studies, UAI was positively associated with fatigue with safer sex, but not fatigue with HIV prevention, among MSM.

Third, the construct of fatalistic beliefs is based on a model of cognitive escapism (Hoyt, Nemeroff, & Huebner, 2006; McKirnan et al., 1996, 2007; Nemeroff et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2000). The model suggests that individuals are motivated to cognitively escape from the threat of risk if they feel incapable of managing the stress because cognitive escape requires less effort than behavioral modification as a strategy (Gerrard et al., 1996; Lazarus, 1966; McKirnan et al., 1996). Contextual factors such as use of drugs and sexually explicit Internet websites play a role as “releasing stimuli” that elicit cognitive escapism, which in turn can lead to UAI among gay men (McKirnan, Vanable, Ostrow, & Hope, 2001; McKirnan, Houston, & Tolou-Shams, 2007). In line with this model, Nemeroff and colleagues (2006, 2008) developed the Cognitive Escape Scale consisting of the following subscales: short-term thinking/fatalism, thought suppression/distraction, and alcohol/substance use. Short-term thinking/fatalism in the scale referred to “fatalistic belief associated with not living long enough for HIV/AIDS to matter” and “engagement in thoughts that are impulsive or focused on the short-term”; thought suppression referred to “attempt to actively and consciously suppress thoughts of HIV when they arise” (p. 307). Their study found that fatalism and thought suppression were significantly associated with UAI among HIV-negative MSM.

In the current study, we were particularly interested in developing a measure that focused on epidemic-related stress in terms of HIV-negative gay men’s social environments (e.g., same-sex relationships) and individual vulnerabilities (e.g., negative self-concept as gay) in a community of high seroprevalence. New York City (NYC), where this study was conducted, has been found to be one of the highest HIV saturation cities in the gay community. According to the CDC (2005), HIV prevalence among MSM was 18% and incidence was 2.3% (95% CI: 0.28%–4.2%) at the time that this study data were collected. Bareback sex (i.e., intentional sex without a condom) has become a common practice in the discourse of gay intimacy, in particular in seroconcordant relationships (Halkitis, Wilton, & Drescher, 2006), and condom use is often excluded from core norms of sexual exchanges in a subgroup of HIV-positive gay men (Clatts, Goldsamt, & Yi, 2005; Kelly et al., 2009). HIV-negative gay men in gay communities of high seroprevalence have reported difficulties in sustaining safer sex and maintaining their serostatus; they also complain of isolation, discomfort, and indifference from other members of the gay community (Odets, 1995). Such stressors may lead them to develop maladaptive responses in contact with sexual networks consisting of HIV-positive gay men (Adam et al., 2005; Kippax et al., 2003; Sheon & Crosby, 2004; Shidlo, 1997).

In preliminary construct validation, we selected three constructs to test validity of the developed measure based on literature of sexual minority stress and psychological correlates of UAI among gay men (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003): (1) internalized homophobia, defined as negative attitudes toward one’s own homosexuality, (2) depression, and (3) multidimensions on self-justifications for sexual risk taking (e.g., self destructiveness, pleasure seeking, intimacy needs, erroneous perception of risk, condom related erectile dysfunction; see Method). Due to stigma attached to homosexuality and HIV/AIDS, a positive self-concept as gay is critical in the development of successful adaptation to the epidemic among gay men. Internalized homophobia was found to be associated with poor health outcomes (Meyer, 2003; Williamson, 2000), passive coping strategies (Nicholson & Long, 1990), and sexual risk practices (Herek & Glunt, 1995; Preston, D’Augelli, Kassab, & Starks, 2007; Williamson, 2000). Research has evidenced the impact of psychological distress and depression on HIV risk related behaviors, such as UAI and use of alcohol and drugs, among gay men (Koblin et al., 2006; Rabkin, 2008; Salomon et al., 2009). High level of depression was also found to be associated with not identifying as gay and increase in isolation from social supports in the gay community among MSM (Mills et al., 2004), concealment of gay identity (Ullrich, Lutgendorf, & Stapleton, 2003), and internalized homophobia (Ross et al., 2001; 2008).

With the study aim of measure development, we tested the following hypotheses: (1) The data fit better a three-factor model – fatalistic beliefs, reduced perceived severity of HIV risk, and anxieties – over a single factor model and items are not cross-loaded on the three factors; (2) Each respective subscale is significantly correlated with the other subscales to a low or moderate degree (e.g., r = .2 to .5); and (3) The measure yields significant positive correlations with the validity measures and UAI.

Method

Subjects

This study involved 285 HIV-negative gay men in an HIV prevention counseling program in NYC between 2003 and 2004. The program has offered multi-session individual, couple, and group HIV risk reduction counseling for gay and bisexual men since 1995. Information about the program was disseminated in the gay community via community-based organizations, gay venues, gay magazines, the advertisements on internet, street outreach, and through existing clients. Clients were interviewed by clinical psychologists: clients under 18 years old were referred to organizations for gay youth, while clients who presented with significant psychological or substance abuse issues were referred for conjoint services. Prior to counseling, clients were informed that the survey was only used for research. Participation was voluntary and did not impact the receipt of counseling services. None of the clients refused study participation. During the intake assessment, we asked the participants about the issues they would like to discuss during counseling sessions. Their motivations for entering program included: same-sex relationship (77.8%), risky or unprotected sex (60.8%), self-esteem (57.6%), depression (45.9%), compulsive sex (43.7%), talk about being HIV-negative (41.1%), discuss HIV serostatus during sex (39.7%), body image/aging (39.0%), sexual partnerships with HIV-negative men (31.4%), negative feeling toward being HIV-negative (29.7%), loss of friends to AIDS (29.5%), relationship with HIV-positive (27.3%), hopelessness (24.7%), using alcohol or drugs during sex (21.5%), coming out as gay (17.1%), suicidal thoughts (11.7%), and sexual abuse (8.6%). The survey took from one hour to one and half hours depending on how much information the participants wanted to share. This study was approved by the hospital where the study was conducted: IRB approval for the use of the data was obtained from the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Procedure

Formative Research: Development of Items

In the development of measure items, we employed inductive and deductive approaches. We first conducted a qualitative pilot study among 60 HIV-negative gay men at an HIV counseling program in NYC, using a sentence completion stem questionnaire about the meaning of being an HIV-negative gay man and sexual relationships: The questionnaire included the following sentences: “For me, being HIV- negative means…”; “Being HIV-negative makes me…”; “Because I am HIV-negative, sex is…”; “Because I am HIV-negative, dating is…”; and “Because I am HIV- negative, talking about HIV status has become…” Based on the themes identified from the qualitative data (Yi, Shidlo, & Koegel, 2004) and a review of the literature, we hypothesized three theoretical factors relevant to the assessment of maladaptive responses to HIV risk1: (1) fatalistic beliefs, defined as cognitive avoidant or ambivalent attitudes toward maintaining an HIV-negative serostatus and the confounding of being gay with developing AIDS in particular in the context of gay relationships; (2) reduced perceived severity, defined as a decrease in perceived medical seriousness of HIV infection and reduced concern with unprotected sex due to HAART; and (3) anxieties, defined as negative affective states (e.g., regret, guilt, grief, and worry) associated with lack of locus of control in regulating safer sex practices and with the risk of HIV infection. The measure consisted of 16 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), read as “We would like you to please circle the number that best describes your feelings about each of the following statements.” The measure items are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Item Description and Internal Consistency of the Measure

| M | SD | ITCS | ITCT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatalistic beliefs (α = .81). | ||||

| 1. It seems like part of being gay/bisexual is also to be HIV-positive, so why aren’t I? | 2.21 | 1.77 | .70 | .51 |

| 2. I don’t look forward to getting older because many of my friends will not be around because of AIDS | 2.50 | 1.94 | .71 | .52 |

| 3. I sometimes feel like giving up because everybody around me is getting HIV. | 2.74 | 1.98 | .71 | .49 |

| 4. I sometimes wonder if it’s worth all the trouble it takes to stay HIV-negative. | 2.31 | 1.91 | .70 | .53 |

| 5. If my partner were going to get HIV, I don’t want to be the one left alone. | 2.10 | 1.83 | .63 | .42 |

| 6. No one really knows what’s safe anymore. I’ll just take my chances. | 2.09 | 1.54 | .54 | .44 |

| Reduced perceived severity (α = .89) | ||||

| 1. Since the discovery of news drugs to fight HIV, I’m less concerned about getting infected | 2.38 | 0.69 | .79 | .33 |

| 2. Now that HIV is manageable disease, I feel more free to have sex without Condoms | 2.35 | 0.66 | .78 | .32 |

| 3. With all the talk of new HIV medicines, AIDS doesn’t seem so scary anymore | 2.67 | 0.82 | .81 | .32 |

| 4. I’m less concerned about getting AIDS now that there are new effective medicines to treat it | 2.31 | 0.61 | .74 | .32 |

| 5. The new antiviral drugs are making it less scary to get AIDS. | 2.71 | 0.87 | .79 | .34 |

| 6. I wouldn’t be so upset if I got infected with HIV because there are powerful new drugs to teat it | 2.27 | 0.58 | .69 | .33 |

| Anxieties (α = .68) | ||||

| 1. I’ve taken chances I regretted the next morning | 2.73 | 1.15 | .79 | .59 |

| 2. I give myself grief about not protecting myself. | 3.11 | 1.03 | .70 | .47 |

| 3. When I get a cold/flu I start worrying that I got infected with HIV. | 2.16 | 1.11 | .64 | .50 |

| 4. I sometimes feel pressured to do risky sex stuff. | 2.11 | 1.95 | .61 | .57 |

| Total scale (α = .78) | ||||

Note: α = Cronbach alpha; ITCS = Item-total correlation for subscale; ITCT = Item-total correlation for total scale

Validity measures

We measured internalized homophobia using the Multi-Axial Gay Attitudes Inventory-Men’s Short Version (MAGI-MSV), a 20-item self-report instrument using a 4-point Likert scale (Shidlo, 1994; Shidlo & Hollander, 1998). The scale has shown preliminary construct validity with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). The scale showed high internal consistency (α = .91) and it consisted of three subscales: (1) self-esteem relating to homosexuality (e.g., “Whenever I think a lot about being gay, I feel depressed.”; α = .87); (2) AIDS-related negative self-image (e.g., “Because of the fear of AIDS, I find myself wishing that I were heterosexual.”; α = .86); and (3) attitudes toward gender-expression, (e.g., “Some gay men are too effeminate.”; α = .79). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to assess depressive symptoms (Beck, 1972). The BDI in this study sample has shown adequate internal consistency (α = .89).

Most of the studies assessing UAI used a dichotomous categorization of safe sex that obscures the different levels of risk associated with specific historical periods, relational contexts, the characteristics of sex partners, and the kind of sexual techniques. We used the Unprotected Anal Intercourse-Attitudes Inventory (UAI-AI), which contains 29 items on 4-point Likert scale to measure the heterogeneity of justifications for the last UAI among HIV-negative gay men (Shidlo, Yi, and Dalit, 2005). The UAI-AI consists of the following six subscales: (1) anger/self destructiveness. When these impulses lead individuals to view HIV infection as a means of punishing oneself or others and it occurs due to a loss of peers to AIDS or to a lack of faith in prevention messages that may be seen as inconclusive (9 items; e.g., “I wanted to hurt myself,”; α = .83), (2) pleasure seeking/escapism. When normal abilities to protect oneself against the risk of HIV infection are affected by substances or especially intense states of sexual arousal, and it occurs when the need for vigilance in sexual contact compete with the desire for pleasure and escape in sex (6 items; e.g., “I was very horny that night and found it hard to control.”; α = .78), (3) intimacy needs. When HIV-negative gay men perceive a condom as a barrier for intimacy exploration (3 items; e.g., “We wanted to feel each other without a condom between us”; α = .77), (4) rational decision making. When HIV-negative gay men determine accurately that the sexual partner does not pose a risk for HIV infection (4 items; e.g., “My boyfriend and I are both negative so we don’t use a condom” α = .72), (5) erroneous perception of risk. When gay men evaluate HIV risk based on the looks, age, or behavior of their partners (4 items; e.g., “He seemed too healthy to be infected”; α = .68), and (6) condom related erectile dysfunction. Some gay and bisexual men find it impossible to sustain an erection when they attempt to use a condom and consequently abandon condom use due to frustration and embarrassment (3 items; e.g., “I can’t get hard when I put a condom on”; α = .73). Participants were also asked about drug use and UAI with a causal sex partner regardless of whether or not they had a steady same-sex partner in the past six months.

Data Analysis

The first step in establishing the psychometric adequacy of the measure was to determine the degree to which responses to the instrument actually reflected the factor structure expected to underlie the measure. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood estimation was performed to test its fit with the observed variance structure of the measured variables. This approach allowed for testing the relative fit of competing single-factor models. Unlike exploratory factor analysis, which inductively identifies the best-fitting solution for a given set of data, CFA begins with a hypothesized model and determines its feasibility by means of assessing how well it fits the existing data (Floyd & Widaman, 1995). As a result, it offers more definitive evidence for the underlying factor structure of a scale. Structural equation modeling on the basis of CFA resolved the concern as to whether the scale consisted of orthogonal or oblique factors and provided a statistical criterion for evaluating how well the real data fit the specified model (DeVellis, 2003). Model feasibility was assessed based on several fit indices. The chi-square goodness-of-fit statistic assessed the magnitude of variance unexplained by the model; this statistic is, however, sensitive to small differences when sample sizes are large. In general, χ2/df below 3 indicates a good fit (Loehlin, 2003). As a result, the following indices, which are known to be less sensitive to sample size, were used in CFA: the Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), which provides an indication of the amount of variance unaccounted for in the model. For the first four indices, values greater than .90 indicate a good fit; for the RMSEA, values equal to or less than .05 indicate a good fit, whereas values in excess of .10 indicate a poor one (Kline, 2004).

Reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (α), squared multiple correlations (R2), inter-item correlations, and item-to-total correlations. An item-to-total correlation higher than .30 is considered acceptable (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). To assess the construct validity of the measure, bivariate correlational analyses were conducted for relationships among the measures and t-tests for UAI. Demographic characteristics were tested for each of the subscales using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests to determine specific differences between subgroups as appropriate. Throughout the statistical procedure, we used LISREL version 8.8 (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1999) and SPSS 15.0.

Results

Characteristics of Participants

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 66 years, with a mean age of 35.6 years (SD = 8.7). The sample was ethnically diverse: 59% White, 13% African-American, 19% Latino/Hispanic, 3% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 6% other ethnicities (i.e. 1% Native American and 5% biracial). The majority of the men (93%) self-identified as gay, and a small number as bisexual (7%, n = 20). Overall, the men reported high educational attainment: 63% college educated and 32% completed graduate school. They were also open about their sexual orientation: 97% had come out to gay friends, 82% to heterosexual friends, 79% to family, and 63% to co-workers. About one third (30%) reported currently being in a same-sex relationship; of those in an ongoing relationship, 27% had an HIV-positive partner and 25% lived together. In the past six months, 66% of the men had multiple sex partners, 48% reported at least one occasion of UAI with casual sex partners, 32% had sex in semi-public venues (e.g., gay bathhouses, gay porn-theaters/video stores, and sex parties) and 12% used club drugs, including crystal-amphetamine, MDMA (known as “ecstasy”), and ketamine.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| % or M | N or SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 35.6 | 8.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 59.1% | 168 |

| Black | 13.3% | 38 |

| Hispanic | 19.0% | 54 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2.8% | 8 |

| Other ethnicities | 5.8% | 17 |

| Sexual identity | ||

| Gay or homosexual | 92.9% | 265 |

| Bisexual | 7.1% | 20 |

| Education attainment | ||

| Completed high school or less | 4.8% | 14 |

| 1–4 years of college | 63.3% | 180 |

| Graduate school | 31.9% | 91 |

| Openness of sexual orientation | ||

| Gay or bisexual friends | 97.0% | 276 |

| Heterosexual friends | 81.7% | 233 |

| Family members | 78.5% | 224 |

| Co-workers | 63.0% | 180 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 70.4% | 201 |

| In relationship | 29.6% | 84 |

| Live with a partner | 25.3% | 21/84 |

| Relationship with an HIV-positive partner | 26.5% | 22/84 |

| In the past six months | ||

| Sexual behavior | ||

| One sex partner | 19.7% | 56 |

| Multiple partners | 66.3% | 189 |

| Didn’t have sex | 14.0% | 40 |

| Unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) a | 48.1% | 137 |

| Only insertive UAI | 40.1% | 55/137 |

| Only receptive UAI | 19.8% | 27/137 |

| Both insertive and receptive UAI | 40.1% | 55/137 |

| Had sex in semi-public sex venues b | 31.9% | 91 |

| Used club drugs c | 11.6% | 33 |

Note. UAI with casual sex partners.

gay bathhouse, gay porn-theaters/video stores, and sex parties.

crystal amphetamine, MDMA - 3.4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine; “ecstasy”, and ketamine.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

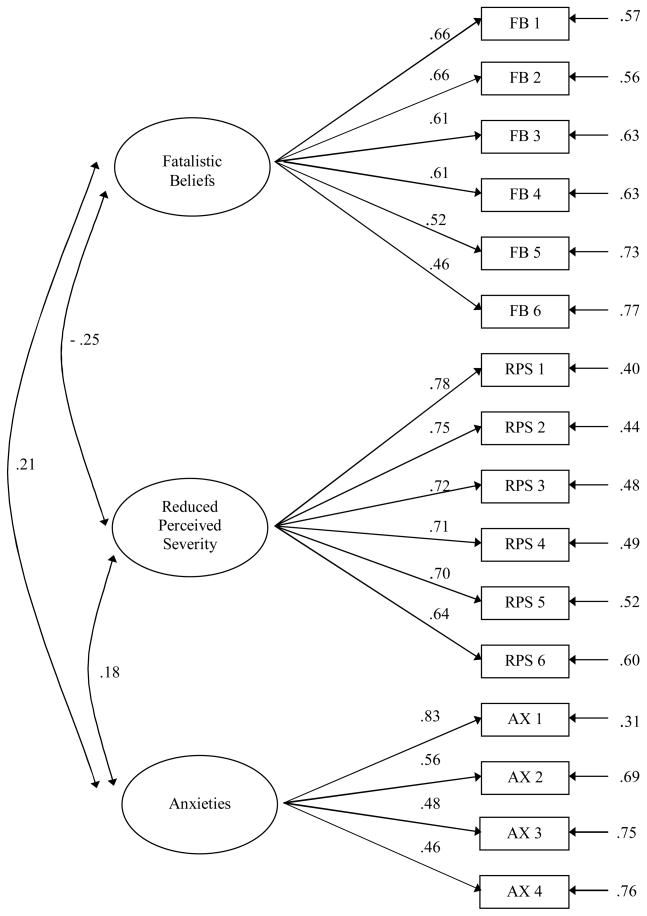

A single-factor model was tested with all items loaded together, while a three-factor model was tested with the loadings of the items based on the hypothesized subscales. Even if the single-factor model is not theoretically plausible, the fit statistics from this model test can be useful in characterizing the degree of superiority of a rival multi-factor model (Thompson, 2004). Table 2 presents the results of these analyses. The CFA of the single-factor model yielded a chi-square of 861.14 (df = 104, χ2/df = 8.28). The other model indices included NNFI = .55, CFI = .61, GFI = .73, and AGFI = .64, RMSEA = .16 (95% CI: .14 – .16). This single-factor model yielded a poor level of fit. The three-factor model yielded a chi-square of 268.19 (df = 101, χ2/df = 2.65, p < .001). NNFI, CFI, GFI, and AGFI values were acceptable (.91, .92, .90, and .87, respectively), and RMSEA was .074 (90% CI: .062 – 090). Compared to the single-factor model, the fit indices’ values in the three-factor model were significantly higher, more closely approaching the generally accepted .90 cutoff, and the RMSEA was lower (.07 compared with .16), more closely approaching the .05 criterion indicative of a good fit. Figure 1 shows the final factor solutions of CFA. The factor loadings ranged from .43 to 83. No item was cross-loaded on more than one factor at the loading > .30. Thus, the three-factor model provided a clearly superior fit for the data compared to the single-factor model and supported the hypothetical constructs in the measure.

Table 2.

Fit Statistics of Single-Factor and Three-Factor Models

| Χ2 | df | NNFI | CFI | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-factor model | 861.14 | 104 | .55 | .61 | .73 | .64 | .160 |

| Three-factor model | 268.19 | 101 | .91 | .92 | .90 | .87 | .074 |

Note. NNFI = Non-Normed Fit Index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; GFI = Goodness of Fit Index; AGFI = Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

Figure 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Chi-square = 268.19, df = 101, p value < .001 RMSEA = 0.074

Reliability

Internal consistency estimates of the scale were tested by conducting three analyses: squared multiple correlations for each item, reliability coefficient alpha scores, correlations among the items and item-to-total scores. The squared multiple correlations (R2) reflected the amount of variance explained for each item, which is referred to as the reliability of each item (see Figure 1; R2 is equal to the square of the factor loading). R2 ranged from .21 to .71. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the measure showed adequate reliability (α = .78). The subscale of reduced perceived severity was shown to be highly reliable (α = .89), while the alpha scores of the other subscales were relatively lower but acceptable: fatalistic beliefs (α = .81), and anxieties (α = .68). The inter-item correlations (r) in the subscales ranged from .21 to .51 in fatalistic beliefs, .34 to .66 in reduced perceived severity, and .16 to .48 in anxieties, and were found to be reliable (Clark & Watson, 1995).

Since internal consistency reliability coefficients are highly affected by the number of tested items as well as the average intercorrelation among the items, the degree of item intercorrelation can be used as a straightforward indicator of internal consistency. Table 3 presents the item-analysis of the measure. Since the measure was intended to identify maladaptive psychological functioning, it required more extreme items than if it were intended to differentiate among normal range individuals (e.g., “No one really knows what’s safe anymore. I’ll just take my chances”, fatalistic beliefs item 5, 27% variance). For that reason, the mean scores of fatalistic beliefs items were relatively lower and their standard deviations are wider than those of other items. All item-to-total correlations (r) were above .60 for subscales and above .40 for the total scale, and were found to be acceptable. All subscales were significantly correlated with each other at the level of p < .05 (see Figure 1). The relationships of subscales that each of the three constructs was related to some degree but also maintains their independence suggested the discriminant validity of the scale.

Validity Tests

Table 4 presents correlations between the subscales and validity measures. Internalized homophobia was positively associated with the total measure of maladaptive responses (r = .29, p < .001) and its subscales of fatalistic beliefs (r = .31, p < .001) and anxieties (r = .20, p < .01). Depression assessed by BDI was also significantly associated with the total measure (r = .26, p < .001) and the subscales of fatalistic beliefs (r = .28, p < .001) and anxieties (r = .18, p < .05). The subscale of reduced perceived severity was not significantly associated with internalized homophobia or depression (r = .08, 09, respectively). With regard to the UAI-AI, significant associations were found between maladaptive responses to HIV risk and the UAI-AI subscales of pressure seeking/escapism (PSE), anger/self-destructiveness (ASD), and erroneous perception of risk (EPR) (r = .34, 33, 20, respectively; all p < .01). In particular, the highest correlations between the subscales that we found were the following: (1) fatalistic beliefs and anger/self-destructiveness (r = .32, p < .001), reduced perceived severity with erroneous perception of risk (r = .20, p < .01), and anxieties with pressure seeking/escapism (r = .28, p < .01). No significant correlation was found between the total measure and the following subscales of the UAI-AI: intimacy needs, rational decision making, and condom related erectile dysfunction.

Table 4.

Correlations with Validity Measures

| UAI-AI |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IH | BDI | ASD | PSE | IN | RCM | EPR | CED | |

| Total scale | .29*** | .26** | .33** | .34** | .01 | .08 | .20** | .07 |

| Fatalistic beliefs | .31*** | .28*** | .32*** | .19** | .02 | .01 | .19** | −.02 |

| Reduced perceived severity | .08 | .09 | .18* | .17* | .07 | .08 | .20** | .02 |

| Anxieties | .20** | .18* | .14* | .28** | −.06 | −.12 | .13 | .10 |

Note. IH = Internalized homophobia. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory. r = .38 (p < .001) between internalized homophobia and BDI. UAI-AI: Unprotected Anal Intercourse-Attitudes Inventory: ASD = Anger/Self-destructiveness; PSE = Pleasure seeking/Escapism; IN = Intimacy needs; RCM = Rational choice making; EPR = Erroneous perception of risk; CED = Condom-related erectile dysfunction.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The behavioral risk factor of having had an UAI with a casual sex partner in the past six months was chosen to test criterion validity (Table 5). Compared to gay men who did not engage in UAI in the past six month, participants who engaged in UAI were more likely to exhibit higher scores on the measure (t = 4.08, p < .001) and its three subscales of fatalistic beliefs, reduced perceived severity, and anxieties (all p < .01).

Table 5.

Univariate Analysis with Unprotected Anal Intercourse

| UAI (N=137) |

Non-UAI (N=148) |

t-test | Effect size (d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Total scale | 2.96 | 1.12 | 2.43 | 1.08 | 4.08*** | .49 |

| Fatalistic beliefs | 2.55 | 1.39 | 2.11 | 1.25 | 2.81** | .33 |

| Reduced perceived severity | 2.64 | 0.73 | 2.26 | 0.54 | 5.02*** | .60 |

| Anxieties | 3.68 | 1.25 | 2.90 | 1.45 | 4.85*** | .58 |

Note. Effect size was calculated by Cohen’s d.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Using univariate analyses, we first examined the mean differences between scores due to sociodemographic characteristics. No significant differences were found for age, ethnicity, education, sexual identity (i.e., gay vs. bisexual men), relationship status (i.e. currently in same-sex relationship vs. not), or serostatus of partners (i.e. relationship with seronegative vs. seropositive). A significant difference between the measure and club drug use was found only in the subscale of reduced perceived severity (t = 2.34, p < .05). ANOVA tests yielded a significant difference in anxieties across the groups by the number of sex partners (i.e. none, single, vs. multiple sex partners), F (2, 276) = 13.51, p < .001. However, post-hoc tests revealed that only one significant difference was found among those men who were not sexually active.

Discussion

Our study findings suggest that the measure we developed in this study reliably and validly assessed the degree of maladaptive responses to the stress of HIV risk in this sample of HIV-negative gay men. The selection of three subscales of fatalistic beliefs, reduced perceived severity, and anxieties was supported by psychometric properties. The construct validity was supported by significant positive associations with the selected validity measures; criterion validity was supported by a comparison between the gay men who engaged in UAI and those who did not. The finding that reduced perceived severity was not related to internalized homophobia and depression but significantly associated with UAI may be explained by several points: (1) perception of severity of HIV infection among gay men has decreased over the course of the advances of HAART so that the effect of treatment optimism on UAI may not be affected by mental health (Crepaz et al., 2004); (2) reduced perceived severity may be an outcome of cognitive dissonance between attitude and behavior rather than an antecedent of behavior (Festinger, 1957): HIV-negative gay men who engage in sexual risk tend to create consistency between their risk behavior and attitudes by changing their beliefs in the severity of HIV (Huebner et al., 2004; Vanable, Ostrow, McKirnan, Taywaditep, & Hope, 2000).

With respect to justification of UAI, all subscales are related to two subscales on the UAI-AI: anger/self-destructiveness (ASD) and pleasure seeking/escapism (PSE). The positive associations with anger-related sexual risk taking suggests that the maladaptive response to the risk of HIV infection may further induce emotional disturbance which promotes poorer control of HIV preventive behaviors. The finding that pleasure seeking/escapism was positively related to the measure supports cognitive escapism as discussed earlier (McKirnan et al., 1996; Nemeroff et al., 2008), and suggests that HIV-negative gay men with maladaptive responses would positively interpret their sexual risk practices. Interestingly, rational choice making (RCM on the UAI-AI) was not related to any of the subscales of the measure, and instead showed a negative correlation with anxiety (r = −.12, p = .074), suggesting that some men may engage in sexual risk taking without exhibiting maladaptive responses. This may be the case, for example, when an HIV-negative gay man chooses to have UAI with an HIV-negative partner to promote intimacy, and does not experience negative affective states.

Lastly, the finding of a negative correlation between fatalistic beliefs and reduced perceived severity supports the notion that multifaceted aspects of psychological adaptations and conflicting maladaptive styles may co-occur in the same individual. In the HIV prevention literature, there is no consensus on what is the most effective or optimal level of emphasizing the severity of the consequences of HIV infection. Stressing the risks of HIV infection to someone who holds ambivalent or conflicting feelings (i.e. fatalistic and or unrealistic optimistic beliefs) about sexual risk is likely to bring unintended effects. A dire portrayal of the negative effects of seroconversion or side effects of HAART may make ambivalent gay men become even more entrenched in their beliefs that there is not a foolproof way to ensure avoiding infection with HIV. On the other hand, they may also argue that HIV seroconversion and the side-effects of HAART are “not so bad” or insist that they do “know” their partner’s serostatus. Therefore, psychological interventions should pay special attention to reducing dissonant beliefs in those who no longer perceive the risk of HIV infection as a primary issue in their life-course as gay.

It is important to contextualize the population of this study in order to better understand the constructs that we attempted to assess. The fact that the gay men in this study came to counseling suggests that they show a positive adaptation to HIV risk by seeking help. Yet, although our participants reported high levels of awareness of increased susceptibility to the risk of HIV infection, many of them had difficulty sustaining safer sex practices with ambivalent attitudes toward maintaining an HIV-negative status. Thus, it is important to note that adaptive and maladaptive responses to the stress of being at risk of HIV infection may co-exist. In addition, as their reasons of entering counseling indicated, many of the participants had several problems with their sexual identity and relationships; about a third lost their friends, loved ones, or family members due to AIDS. These multiple (post-traumatic) stressors might converge to cause maladaptive responses to the epidemic among the gay men.

Although the findings suggest that the developed measure can be used as a psychological assessment tool in research and intervention among HIV-negative gay men in situations where the epidemic history is similar to NYC, several limitations must be acknowledged. The internal consistency of the scales was satisfactory but requires improvement. The relatively lower coefficients obtained for anxieties concerning sexual risk might be attributable to the fact that only four items were used to assess a wide range of affective states that would be invoked by sexual risk practices. Together with refinement of this assessment, further scale validation research is needed with measures such as sexual partnerships, networks, and setting, and post-hoc appraisal of the risk experiences. With regard to study population, this research did not feature a random sample of men who have sex with men who might not self-identify themselves as gay or involved in gay community services. The typical participants in this study had at least a college education and, most importantly, were self-identified gay men living in a metropolitan area of high seroprevalence among MSM. Since it is a treatment seeking and highly educated sample, the participants were likely to be more psychologically minded, which might have implications for responding to the study assessments. The participants generally had a high level of openness about their sexual orientation. The items and constructs measured may not reflect the different aspects of sociodemographic backgrounds and sexual identity. Thus, replication with a diverse population of gay men who were not part of this sample (e.g., gay men who live in places of low seroprevalence) is essential to evaluate the stability of the factor structure, measurement invariance, reliability, and validity.

The psychological assessment of characteristic ways in which HIV-negative gay men respond to epidemic-related stressors will provide theoretical and practical insights to understand sexual risk taking among HIV-negative gay men who live in areas of high seroprevalence. Future research should develop more integrative measures assessing broad dimensions of coping and resilience to stress of HIV risk. Longitudinal research would be helpful to examine of changes of adaptation styles, which can be critical in the refinement of interventions in HIV prevention. Theoretical and methodological applications in these areas should lead to a discussion of future research on identifying, conceptualizing, and measuring the dimensions of adaptive and maladaptive responses to the continuing epidemic. For this reason, the issues of measure development in this area deserve attention and visibility. The phenomena of “epidemic fatalism and treatment optimism” may not be considered as new in the gay communities, but these issues are still new as targets of prevention interventions. Rather than unrealistic fatalistic and optimistic beliefs as impediments to prevention efforts, understanding the dynamics of those adaptations could serve as a key focus of individual and community-level prevention to reduce ecological stressors relating to HIV/AIDS among gay men living in the third decade of the epidemic and to re-construct a more resilient environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in this research for their time and express gratitude to talkSafe staff and peer counselors who worked above all for the well being of gay men. talkSafe was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant funding, given through the New York City Department of Health to the Medical and Health Research Association of New York City, Inc. The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of talkSafe and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. This research was also supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH19139, Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection; Principal Investigator: Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D.) and a center grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (P30-MH43520; Principal Investigator: Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D.)

Footnotes

We initially developed, another construct, mutuality in serodiscordant dyad, to assess relationship issues affected by the imbalance that HIV illness can cause (e.g., fear of the seropositive partner dying and lack of communication between the partners) since the relationship with HIV-positive gay men is an important area to explore in terms of psychological adaptation to the epidemic. However, the subscale was excluded from the analysis due to a small sample size in the current study. Only 8% (n=22/285) of the subjects reported that they were currently in a relationship with an HIV-positive partner.

References

- Adam BD, Husbands W, Murray J, Maxwell J. AIDS optimism, condom fatigue, or self-esteem? Explaining unsafe sex among gay and bisexual men. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42:238–248. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austenfeld JL, Stanton AL. Coping through emotional approach: a new look at emotion, coping, and health-related outcomes. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1335–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Measuring depression: The depression inventory. In: Williams TA, Katz MM, Shields JA, editors. Recent Advances in the Psychobiology of the Depressive Illnesses. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1972. pp. 299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Cognitive-behavioral stress management interventions for persons living with HIV: A review and critique of the literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35:26–40. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9010-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevalence, unrecognized infection, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men five U.S. Cities, June 2004 April 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2005;54(24):597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent Areas, 2006. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 2008;18 [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:309–319. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Goldsamt LA, Yi H. Emerging HIV risk environments: A preliminary epidemiological profile of an MSM POZ party. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:373–376. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.127.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review. Journal of American Medical Association. 2004;292:224–236. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVillis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Elford J. HIV treatment optimism and high-risk sexual behavior among gay men: The attributable population risk. AIDS. 2004;18:2216–2217. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411050-00021. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/toc/2004/11050. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Elford J. Changing patterns of sexual behaviour in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2006;19:26–32. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000199018.50451.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:286–299. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazraus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Social Science and Medicine. 1988;26:309–317. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Bushman BJ. Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:390–409. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold RS, Aucote HM. “I’m less at risk than most guys”: Gay men’s unrealistic optimism about becoming infected with HIV. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2003;14:18–23. doi: 10.1258/095646203321043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold RS, Skinner MJ. Gay men’s estimates of the likelihood of HIV transmission in sexual behaviours. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2001;12:245–255. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis P, Gomez CA, Wolitski RJ. HIV+ sex. The psychological and interpersonal dynamics of HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men’s relationships. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Wilton L, Drescher J. Barebacking: Psychosocial and public health approaches. Binghamton, New York: Haworth Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM …HIV Incidence Surveillance Group. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. Journal of American Medical Association. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW. Sex isn’t that simple: Culture and context in HIV prevention interventions for gay and bisexual male adolescents. American Psychologist. 2007;62:803–819. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Glunt EK. Identity and community among gay and bisexual men in the AIDS era: Preliminary findings from the Sacramento Men’s Health Study. In: Herek GM, Greene B, editors. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay issues: AIDS, identity, and community: The HIV epidemic and lesbian and gay men. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt MA, Nemeroff CJ, Huebner DM. The effects of HIV-related thought suppression on risk behavior: cognitive escape in men who have sex with men. Health Psychology. 2006;25:455–461. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. A longitudinal study of the association between treatment optimism and sexual risk behavior in young adult gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2004;37:1514–1519. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000127027.55052.22. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/jaids/toc/2004/12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ironson G, Hayward H. Do positive psychosocial factors predict disease progression in HIV-1? A review of the evidence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(5):546–554. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177216c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL 8 user’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, Izienicki H, Parsons JT. Stress and coping among HIV-positive barebackers. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:792–797. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S, Race K. Sustaining safe practice: twenty years on. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S, Slavin S, Ellard J, Hendry O, Richters J, Grulich A, Kaldor J. Seroconversion in context. AIDS Care. 2003;15:839–852. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001618685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang Y, Madison M, Mayer K, …Buchbinder S. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20(5):731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Livneh H, Livneh CL, Maron S, Kaplan J. A multidimensional approach to the study of the structure of coping with stress. The Journal of Psychology. 1996;130(5):501–512. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1996.9915017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent variable models. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JI, Pryce JG, Leeper JD. Avoidance coping and HIV risk behavior among gay men. Health and Social Work. 2005;30(3):193–201. doi: 10.1093/hsw/30.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Sex, drugs and escape: A psychological model of HIV-risk sexual behaviors. AIDS Care. 1996;8:655–669. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Vanable PA, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Expectancies of sexual “escape” and sexual risk among drug and alcohol-involved gay and bisexual men. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:137–154. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan D, Houston E, Tolou-Shams M. Is the Web the culprit? Cognitive escape and Internet sexual risk among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:151–160. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Dean L. Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. In: Herek GM, editor. Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 160–186. [Google Scholar]

- Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, Pollack L, Canchola J, Chang YJ, …Catania JA. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:278–285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278. Retrieved from http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/161/2/278. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mosack KE, Weinhardt LS, Kelly JA, Gore-Felton C, McAuliffe TL, Johnson MO, …Morin SF. Influence of coping, social support, and depression on subjective health status among HIV-positive adults with different sexual identities. Behavioral Medicine. 2009;34:133–144. doi: 10.3200/BMED.34.4.133-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff CJ, Hoyt MA, Huebner DM, Proescholdbell RJ. The cognitive escape scale: Measuring HIV-related thought avoidance. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:305–320. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WD, Long BC. Self-esteem, social support, internalized homophobia, and coping strategies of HIV+ gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:873–876. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Berstein IH. Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Odets WW. In the shadow of the epidemic: Being HIV-negative in the age of AIDS. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow DE, Fox KJ, Chmiel JS, Silvestre A, Visscher BR, Vanable PA, …Strathdee SA. Attitudes towards highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with sexual risk taking among HIV-infected and uninfected homosexual men. AIDS. 2002;16:775–780. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00013. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/toc/2002/03290. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ostrow DG, Silverberg MJ, Cook RL, Chmiel JS, Johnson L, Li X Multicenter AIDS cohort study. Prospective study of attitudinal and relationship predictors of sexual risk in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:127–138. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston DB, D’Augelli AR, Kassab CD, Starks MT. The relationship of stigma to the sexual risk behavior of rural men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19(3):218–230. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.291.40401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg VS, Boucsein W. Adaptive versus maladaptive emotional tension. Genetic, Social, General Psychology Monograph. 1993;119(2):209–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Simon Rosser BR, Bauner GR, Bockting WO, Robinson BE, Ruggs DL, …Coleman E. Drug use, unsafe sexual behavior, and internalized homonegativity in men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5:97–103. doi: 10.1023/A:1009567707294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rosser BR, Neumaier ER Positive Connections Team. The relationship of internalized homonegativity to unsafe sexual behavior in HIV-seropositive men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2008;20:547–557. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.6.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon EA, Mimiaga MJ, Husnik MJ, Welles SL, Manseau MW, Montenegro AB, …Mayer KH. Depressive symptoms, utilization of mental health care, substance use and sexual risk among young men who have sex with men in EXPLORE: Implications for age-specific interventions. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:811–821. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9439-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Fielder RL. Stress management interventions for HIV+ adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, 1989 to 2006. Health Psychology. 2008;27:129–139. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheon N, Crosby MG. Ambivalent tales of HIV disclosure in San Francisco. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;58:2105–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidlo A. Internalized homophobia: Conceptual and empirical issues in measurement. In: Greene B, Herek Gregory M, editors. Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 176–205. [Google Scholar]

- Shidlo A. Mental health issues of HIV negative gay men. In: Winiarski MG, editor. HIV mental health for the 21st century. New York: New York University Press; 1997. pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Shidlo A, Hollander G. Assessing internalized homophobia: New empirical findings; Paper resented at the 106th American Psychological Association Convention; San Francisco, CA. 1998. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Shidlo A, Yi H, Dalit B. Attitudes toward unprotected anal intercourse: Assessing HIV-negative gay or bisexual men. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy. 2005;9(3/4):111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Stall RD, Hays RB, Waldo CR, Ekstrand M, McFarland W. The Gay ‘90s: A review of research in the 1990s on sexual behavior and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 3):S101–S114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman JK, Schwarcz SK, Butler LM, de Jong B, Chen SY, Delgado V, McFarland W. HIV prevention fatigue among high-risk populations in San Francisco. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2004;35:432–434. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404010-00016. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/jaids/toc/2004/04010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thompson B. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich PM, Lutgendorf SK, Stapleton JT. Concealment of homosexual identity, social support, and CD4 cell count among HIV-seropositive gay men. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2003;54:205–212. doi: 10.1016/S0022–3999(02)00481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdiserri RO. Mapping the roots of HIV/AIDS complacency: implications for program and policy development. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:426–439. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.5.426.48738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Ostrow DG, McKirnan DJ, Taywaditep KJ, Hope BA. Impact of combination therapies on HIV risk perceptions and sexual risk among HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay and bisexual men. Health Psychology. 2000;19:134–145. doi: 10.I037//0278-6133.19.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S, Lord L. Denial: A conceptual analysis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1999;13(6):311–320. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9417(99)80063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ML, Elwood WN, Bowen AM. Escape from risk: A qualitative exploration of relapse to unprotected anal sex among men who have sex with men. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 2000;11:25–49. doi: 10.1300/J056v11n04_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson IR. Internalized homophobia and health issues affecting lesbians and gay men. Health Education Research. 2000;15:97–107. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.97. Retrieved from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/15/1/97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wolitski RJ, Valdiserri RO, Denning PH, Levine WC. Are we headed for a resurgence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men? American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:883–888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.883. Retrieved from http://www.ajph.org/cgi/reprint/91/6/883.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yi H, Shidlo A, Koegel H. Thematic analysis of HIV-negative identity and sexual risk among gay men in New York City. Presented at the 15th International AIDS Conference; Bangkok Thailand. 2004. Jul, [Google Scholar]