Abstract

Perceived partner responsiveness is a core feature of close, satisfying relationships. But how does responsiveness originate? Can people create relationships characterized by high responsiveness, and consequently, higher quality relationships? We suggest that goals contribute to cycles of responsiveness between people, improving both people’s relationship quality. The present studies examine 1) how interpersonal goals initiate responsiveness processes in close relationships, 2) the self-perpetuating nature of these processes, and 3) how responsiveness evolves dynamically over time through both intrapersonal projection and reciprocal interpersonal relationship processes. In a semester-long study of 115 roommate dyads, actors’ compassionate and self-image goals predicted a cycle of responsiveness between roommates, occurring within weeks and across the semester. In a 3-week study of 65 roommate dyads, actors’ goals again predicted cycles of responsiveness between roommates, which then contributed to both actors’ and partners’ relationship quality. Results suggest that both projection and reciprocation of responsiveness associated with compassionate goals create upward spirals of responsiveness that ultimately enhance relationship quality for both people.

Creating Good Relationships: Responsiveness, Relationship Quality, and Interpersonal Goals

High quality close relationships contribute to mental and physical well-being; poor quality close relationships create stress and undermine health and well-being (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996). Relationship quality depends on beliefs about a relationship partner’s responsiveness--that is, on the perception that a partner understands, values, and supports important aspects of the self. People who perceive their relationship partners as responsive feel close, satisfied, and committed to those relationships (Reis, Clark, & Holmes, 2004).

The present studies focus on the dynamic of responsiveness in dyadic relationships -- relationship processes that promote or undermine reciprocation of responsiveness between relationship partners, affecting both partners’ relationship quality over time. We suggest that people’s interpersonal goals for their relationships, that is their compassionate goals to support others and their self-image goals to create and maintain desired self-images (Crocker & Canevello, 2008), predict positive and negative responsiveness dynamics respectively, changing both people’s relationship quality. In this way, people can create responsive, high-quality relationships for themselves and others.

Responsiveness in Relationships

Responsive relationship partners convey understanding, validation, and caring (Gable & Reis, 2006). They are warm, sensitive to their partners’ feelings, and want to make their partners feel comfortable, valued, listened to, and understood.

Existing theory and research on responsiveness suggests that people’s responsiveness to partners contributes to both their own and partners’ perceptions of responsiveness in the relationship. Lemay and colleagues (Lemay & Clark, 2008; Lemay, Clark, & Feeney, 2007) found that people contribute to their own experiences of responsiveness in close relationships; when people report being responsive to relationship partners, they project their responsiveness onto partners and perceive partners as more responsive. Other researchers characterize responsiveness as a transactional process between relationship partners. Reis and Shaver (1988) hypothesize that close relationships develop through an interpersonal process in which actors’ reactions to partners influence partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness. Importantly, Reis and Shaver speculate that goals, motives, needs, and fears of both relationship partners contribute to and result from responsiveness in the relationship. That is, goals and motives predict people’s relationship behaviors and how they interpret partners’ behaviors, which in turn, feed back to predict goals and motives.

The present studies examine both intrapersonal and interpersonal processes of responsiveness and contribute to the responsiveness literature in three important ways. First, as suggested by Reis and Shaver (1988), interpersonal goals should predict responsiveness processes in close relationships. However, no research that we know of explicitly examines the motivational underpinnings of responsiveness, whether based on projection or reciprocation. We propose that actors’ compassionate goals to support others and self-image goals to construct and maintain desired self-images shape their responsiveness to relationship partners. Through projection, actors’ responsiveness affects their perceptions of their partners’ responsiveness, and hence their own relationship experiences. Through partners’ perceptions and reciprocation of actors’ responsiveness, actors’ responsiveness affects both actors’ and partners’ relationship experiences. We suggest that because projection is an intrapersonal processes and the exchange of responsiveness between relationship partners is an interpersonal process, both can occur simultaneously. That is, people can project their responsiveness onto others, affecting their own relationship experiences, and at the same time, convey responsiveness to relationship partners, affecting partners’ relationship experiences.

Second, projected and reciprocated responsiveness can become self-perpetuating: relationship goals promote or undermine projection and reciprocation of responsiveness, which reinforce both people’s subsequent relationship goals. Thus, through their interpersonal goals, people can create responsive, high-quality relationships for themselves and others and contribute to both people’s goals for the relationship.

Third, to our knowledge, the present studies are the first to examine both immediate and long-term intra- and interpersonal responsiveness dynamics and resulting relationship outcomes as they evolve over time. Previous research suggests that these processes should occur quickly within relationships, guiding people’s relationship experiences and goals in the moment (e.g., Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998; Lemay et al., 2007). We hypothesize that the effects of compassionate and self-image goals and responsiveness extend over time, predicting change in people’s relationship experiences and goals from day to day and week to week, and that chronic interpersonal goals predict long-term changes in relationship experiences and interpersonal goals over weeks and months. Thus, we propose that projection of responsiveness and reciprocation of responsiveness dynamically affect short-term fluctuations and long-term changes in relationship outcomes.

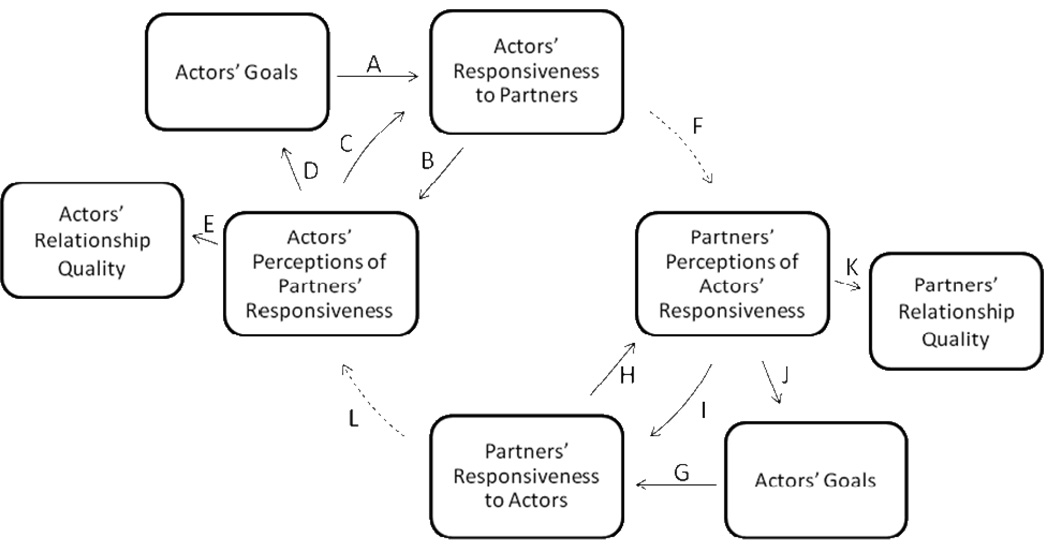

Figure 1 illustrates our general model in a relationship between an actor (A) and a relationship partner (P). We highlight intra- and interpersonal aspects of the model and detail them below.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized theoretical model of interpersonal goals, responsiveness, and relationship quality.

Intrapersonal Process: A’s Compassionate and Self-Image Goals and Responsiveness Predict A’s Relationship Experience

We hypothesize an intrapersonal model examining how people’s goals contribute to their own experiences of responsiveness and resulting relationship goals and quality. Our model extends the intrapersonal projection of responsiveness described by Lemay and colleagues (Lemay & Clark, 2008; Lemay et al., 2007), by showing how actors’ goals can be the starting point for change in their responsiveness to partners, which is projected onto partners and leads to change in actors’ goals and relationship outcomes. Paths A–E in Figure 1 show our hypothesized intrapersonal model of goals and responsiveness: A’s interpersonal goals predict change in A’s responsiveness (Path A), which predicts change in A’s perceptions of P’s responsiveness (Path B), with consequences for change in A’s subsequent responsiveness (Path C), goals (Path D), and relationship quality (Path E).

Paths G–K of Figure 1 are a mirror image of the intrapersonal processes in paths A–E, but for partners rather than actors: P’s compassionate goals predict P’s increased and self-image goals predict P’s decreased responsiveness to A (Path G). P’s responsiveness to A predicts P’s increased perceptions of A’s responsiveness (Path H), which then leads to P’s increased responsiveness (Path I), increased compassionate and decreased self-image goals (Path J), and increased relationship quality (Path K).

Below, we present the rationale for each path in the intrapersonal model.

Path A: A’s compassionate and self-image goals predict change in A’s responsiveness

We propose that two types of relationship goals shape responsiveness to relationship partners. Self-image goals focus on constructing, maintaining, and defending desired public and private images of the self (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). When people have self-image goals, they care about what others think of them, but not what others need; consequently they should be less responsive. Compassionate goals focus on supporting others, not to obtain something for the self, but out of concern for others’ well-being (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). When people have compassionate goals, they want to be a constructive force in their interactions with others, and avoid harming them. We suggest that when people have compassionate goals they are more responsive, because they care about others’ well-being.1

People with chronically high compassionate goals report greater private self-consciousness, lower psychological entitlement, believe that it is possible for both people in a relationship to have their needs met, and believe that it is important that people look out for one another; they trust in and feel closer to others and report both giving and receiving more social support (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). These findings suggest that when people have compassionate goals they understand and trust that when they are responsive to others, they create an environment in which others will respond to them. In contrast, people with chronically high self-image goals report higher psychological entitlement, believe that good outcomes for one person come at the expense of others, and feel that it is important to look out for themselves, even at the expense of others; they report higher loneliness, more conflict with others, and lower interpersonal trust (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). These findings suggest that when people have self-image goals they feel a sense of scarcity and fear that their needs will not be met in collaboration with others. Based on these findings, we propose Path A: When A has the goal to care for and support P, A will become more responsive to P, whereas when A has the goal to create and maintain desired self-images, A will become less responsive to P.

Path B: A’s responsiveness to P predicts A’s increased perceptions of P’s responsiveness

When actors believe they are responsive to partners, they project their own responsiveness onto partners and perceive partners as more responsive (Kenny & Acitelli, 2001; Lemay & Clark, 2008; Lemay et al., 2007). Several factors might moderate this association. For example, actors who have low self-esteem might feel their partners do not value them and perceive their partners as unresponsive (Murray, Griffin, Rose, & Bellavia, 2003). Also, because of their over-involvement with others and self-neglect, actors high in unmitigated communion might want to see themselves as self-sacrificing and see their partners as unresponsive (Helgeson & Fritz, 1998). However, despite these specific circumstances, in general we expect a strong association between responsiveness and perceptions of partners’ responsiveness. These considerations lead us to propose Path B: A’s responsiveness to P predicts A’s increased perceptions of P’s responsiveness.

Path C: A’s perception of P’s responsiveness predicts A’s increased responsiveness to P

When actors perceive their partners as responsive, they are more responsive in return; when they perceive their partners as unresponsive, actors are less responsive in return (Fruzzetti, Jacobson, & Blechman, 1990; Gable & Reis, 2006; Patterson, 1976; Plickert, Côté, & Wellman, 2007). This may happen for several reasons. People may reciprocate responsiveness out of caring. Actors’ responsiveness strengthens partners’ social bonds to actors, including feelings of caring, connection, and trust, leading partners to want to be responsive to actors (e.g., Brown & Brown, 2006; Clark, Fitness, & Brissette, 2004). In established communal relationships, partners experience more positive mood and less negative mood when they reciprocate support to actors, compared to when they do not (Gleason, Iida, Bolger, & Shrout, 2003). Even in new relationships, reciprocity of responsiveness may be the result of social exchange norms in which both partners focus on an equal exchange of responsiveness (Clark & Mills, 1993; Mills & Clark, 1982). Given this evidence, we propose Path C: A’s perception of P’s responsiveness predicts A’s increased responsiveness to P.

Path D: A’s perception of P’s responsiveness predicts change in A’s compassionate and self-image goals

Actors’ perceptions of partners’ responsiveness should shape actors’ compassionate and self-image goals toward the partner. Actors who perceive partners as responsive feel validated, understood, and cared for (Reis et al., 2004), which fosters a sense of security and permits a shift in focus from protecting the self to supporting others (Mikulincer, Shaver, Gillath, & Nitzberg, 2005; Murray, Holmes, & Collins, 2006). In other words, actors’ feelings that partners are responsive to them should foster compassionate goals for partners. Unresponsiveness, on the other hand, conveys a partners’ lack of interest in or concern for actors. Perceptions of partners’ unresponsiveness may signal to actors that they should protect themselves from uncaring partners (Clark & Monin, 2006; Murray et al., 2003; Murray, Rose, Bellavia, Holmes, & Kusche, 2002) and, as a result, actors should increase in self-image goals. These considerations lead us to propose Path D: A’s perception of P’s responsiveness predicts A’s increased compassionate and decreased self-image goals.

Path E: A’s perception of P’s responsiveness predicts A’s increased relationship quality

Perceived partner responsiveness is crucial to relationship quality (Clark & Mills, 1993; Laurenceau et al., 2004; see Reis et al., 2004 for a review). Actors who believe that partners are responsive feel closer, more intimate, and more satisfied with their relationships (Berg & Archer, 1982; Collins & Feeney, 2000; Cutrona, Shaffer, Wesner, & Gardner, 2007; Davis, 1982; Laurenceau et al., 1998; Lemay et al., 2007). When actors perceive partners as unresponsive, they experience decreased satisfaction, commitment, and closeness in those relationships (Fincham & Beach, 1999; Gottman & Levenson, 1992). Consequently, we predict Path E: A’s perception of P’s responsiveness predicts A’s increased relationship quality.

Interpersonal Process: A’s compassionate and self-image goals and responsiveness lead to P’s relationship experience and goals

In addition to this purely intrapersonal process, we hypothesize an interpersonal model in which people’s goals and responsiveness contribute to relationship partners’ experience of actors’ responsiveness, leading to reciprocation of responsiveness and resulting relationship goals and quality. We draw from previous theory and research suggesting that responsiveness is a dyadic process whereby partners perceive actors’ responsiveness and respond in turn (e.g., Collins & Feeney, 2000; Reis & Shaver, 1988). We hypothesize that actors’ goals can also be the starting point for creating responsiveness dynamics between relationship partners, with consequences for partners’ responsiveness to actors, goals, and relationship quality. Paths A, F, I, J, and K in Figure 1 depict our interpersonal model, in which A’s goals predict change in A’s responsiveness to partners (Path A), which predicts change in P’s perceptions of A’s responsiveness (Path F), with consequences for change in P’s subsequent responsiveness (Path I), goals (Path J), and relationship quality (Path K).

Paths G, L, C, D, and E of Figure 1 are a mirror image of the interpersonal processes in Paths A, F, I, J, and K, but show effects of partners’ goals and responsiveness on change in actors’ relationship experiences: P’s compassionate and self-image goals predict change in P’s responsiveness to A (Path G). P’s responsiveness to A predicts A’s increased perceptions of P’s responsiveness (Path L), which then leads to A’s increased responsiveness, increased compassionate and decreased self-image goals, and increased relationship quality (Paths C, D, and E).

Path A: A’s compassionate and self-image goals predict change in A’s responsiveness

As described previously in our rationale for the intrapersonal model, we propose Path A: that A’s interpersonal goals predict change in A’s responsiveness to P.

Path F: A’s responsiveness predicts P’s increased perceptions of A’s responsiveness

Relationship researchers assume that partners’ perceptions of actors have some basis in actors’ behaviors (Kelley et al., 1983). Most theories of interpersonal relationships assume that actors’ responsiveness to partners predicts partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness (e.g. Bowlby, 1969; Gable & Reis, 2006; Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; I. G. Sarason, Pierce, & Sarason, 1990); empirical research supports this prediction (Abbey, Andrews, & Halman, 1995; Bolger, Zuckerman, & Kessler, 2000; Collins & Feeney, 2000; Feeney & Collins, 2003; Lemay & Clark, 2008; Vinokur, Schul, & Caplan, 1987). For example, in romantic couples when actors disclosed a stressful problem to partners, partners’ reports of their own responsiveness (i.e., responsiveness, listening, understanding, not criticizing, giving support, and expressing concern) positively predicted actors’ perceptions of partners’ responsiveness (Collins & Feeney, 2000). Consequently, we propose Path F: A’s responsiveness to P predicts P’s increased perceptions of A’s responsiveness.

Paths I, J, and K: P’s perceptions of A’s responsiveness and change in P’s relationship experience

Using the same rationale to describe Paths C, D, and E previously, we propose Paths I, J, and K, respectively: P’s perceptions of A’s responsiveness has consequences for P’s increased responsiveness (Path I), increased compassionate and decreased self-image goals (Path J) and increased relationship quality (Path K).

Overview of Present Studies

In two studies of first-semester college freshman roommates, we tested 1) how interpersonal goals initiate projection and reciprocal responsiveness in close relationships, 2) the self-perpetuating nature of these processes, and 3) how responsiveness evolves dynamically over time through both intrapersonal projection and reciprocal interpersonal relationship processes. First semester college students provide an interesting population for examining these processes. Roommates in these samples did not know each other before living together, so their relationships are relatively unbiased by relationship history and past interactions. Unlike most close relationships, previously unacquainted roommates do not self-select into the relationship. At the same time, many first-year students experience significant disruption of their social lives. When they move away from home to attend college, they must build a social network. Their roommates are often the first people they meet and with whom they spend significant time.

Study 1 tested whether students’ compassionate and self-image goals predict a cycle of projected and reciprocal responsiveness between roommates with implications for both people’s relationship goals. Study 2 reports previously unpublished data from the Roommate Goals Study (Crocker & Canevello, 2008, Study 2), examining the implications of these processes for both roommates’ relationship quality.

STUDY 1

College roommates completed pretest, posttest, and 10 weekly questionnaires, each including measures of compassionate and self-image goals, responsiveness to roommates, and perceived roommates’ responsiveness. We tested associations between students’ goals and 1) the intrapersonal process predicting their own experiences of responsiveness, and 2) the interpersonal process predicting their roommates’ experiences of responsiveness.

We tested a number of alternative explanations and moderators of these processes in Study 1. First, self-disclosure elicits responsiveness from others (e.g., Greene, Derlega, Mathews, Vangelisti, & Perlman, 2006; Reis & Patrick, 1996; Reis & Shaver, 1988). Associations between goals and responsiveness to roommates could be due to perceptions of roommates’ disclosure, and associations between responsiveness to roommates and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness could be due to disclosure to roommates.

Second, we sought to distinguish responsiveness from social support. Previous research shows that compassionate and self-image goals predict change in perceived available support and supportive behaviors (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). The present studies focus on responsiveness, which we hypothesize is a specific type of support. Support is often broadly defined, including perceptions of support availability and frequency of supportive behaviors (B. R. Sarason, Shearin, Pierce, & Sarason, 1987) and includes structural (e.g., group membership or family relationships) and functional components (e.g., providing tangible or emotional support) (Uchino, 2004). Responsiveness refers to people’s sensitivity to partners and desires that partners feel valued, listened to, and understood. Researchers differ in how they view the relation between responsiveness and support; some argue that support is a component of responsiveness (e.g., Reis et al., 2004); others conceptualize responsiveness as a subset of social support, distinguishing between responsive and unresponsive support (e.g., Collins & Feeney, in press). Regardless, researchers agree that responsiveness and support are distinct but related constructs; support providers may not be perceived as responsive. We tested whether support made available to roommates and perceived available social support from roommates explained the effects of responsiveness to roommates and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness, respectively.

Third, we examined whether negative mood accounts for or moderates the hypothesized associations. For example, the association between interpersonal goals and responsiveness to others might be spurious, if both are associated with anxious or depressed feelings. Feeling anxious or depressed might also moderate these associations. For example, the relation between responsiveness to roommates and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness may be particularly strong when people do not feel anxious or depressed.

We controlled for students’ self-disclosure to their roommates and their perceptions of their roommates’ disclosure, social support made available to and perceived available support from roommates, and anxiety and depression to rule them out as alternative explanations.

Method

Participants

One hundred fifteen first-semester same-sex freshmen roommate dyads at a large Midwestern university who did not know each other prior to college volunteered for a study of goals and roommate relationships during the fall semester. Via advertisements in the campus newspaper and flyers, we offered each roommate $60 for completing 12 surveys over 10 weeks ($10 for each the pretest and posttest and $4 for each weekly survey) plus a $40 bonus for completing all 12 surveys. One hundred nine pairs (95%) completed the pretest, posttest, and at least 8 weekly surveys. Although 6 pairs completed fewer parts of the study, we retained all data for analyses where possible.2 Eighty-six pairs (75%) were female. Seventy-five percent of participants reported their race as White or European-American, 2% as Black or African-American, 15% as Asian or Asian-American, and 8% selected other. The racial composition of the sample closely approximated the racial composition of the incoming freshman class. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 21 years (M = 18.1 years, SD = .36).

Procedure

In groups of 1 to 8, roommate pairs attended a 1.5 hour session to learn about the study, give their consent, complete the pretest survey, and receive instructions for completing the remaining 11 surveys. All surveys were administered using UM Lessons software. After completing the pretest survey, participants were instructed to complete the 10 weekly online surveys in privacy and not to discuss their responses with each other. The weekly surveys took about 30 minutes to complete and roommates were required to complete weekly surveys within no less than 48 hours of each other. To retain as many participants as possible in the study, participants were given up to 11 weeks to complete the 10 weekly surveys.3 Once roommates had completed 10 weekly surveys, they completed the posttest survey and were paid for their participation.

Measures

Participants completed measures of compassionate and self-image goals, responsiveness to roommates, perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness, disclosure to and from roommates, support made available to roommates, available support from roommates, anxiety, and depression at pretest, posttest, and weekly. At pretest, participants completed questions about demographics (gender, race/ethnicity, age, parental income). Additional measures not germane to the goals of the present investigation were also included.

Self-image and compassionate goals for participants’ relationships with their roommates were measured using a modified measure from Crocker & Canevello (2008). Pretest and posttest items began with the phrase, “In my relationship with my roommate, I want/try to." Weekly items began with “This week, in my relationship with my roommate, I wanted/tried to.” All items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Eight items assessed compassionate goals: “be supportive of my roommate;” "have compassion for my roommate's mistakes and weaknesses;" "be aware of the impact my behavior might have on my roommate's feelings;" “make a positive difference in my roommate’s life;” "avoid neglecting my relationship with my roommate;" "avoid being selfish or self-centered;" "be constructive in my comments to my roommate;" and "avoid doing things that aren’t helpful to me or my roommate." Six items reflected self-image goals, including "avoid showing my weaknesses;" “avoid revealing my shortcomings or vulnerabilities;” "avoid the possibility of being wrong;" "convince my roommate that I am right;" "get my roommate to do things my way;" and "avoid being blamed or criticized." Both scales had high internal consistency at pretest (self-image α = .79; compassionate α = .75), posttest (self-image α = .87; compassionate α = .94), and across participants and weeks (self-image goals: .83 < α < .91, Mα = .88; compassionate goals: .85 < α < .94, Mα = .91).

Responsiveness to roommates and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness were measured with a 6-item modified version of a responsiveness measure used in previous research (Cutrona, Hessling, & Suhr, 1997; Gore, Cross, & Morris, 2006). Participants indicated how they acted toward their roommate in general at pretest and posttest. All items were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Items included “I try to make my roommate feel comfortable about him/herself and how he/she feels;” "I try to make my roommate feel valued as a person;" "I try to be sensitive to my roommate’s feelings;" “I really try to understand my roommate’s concerns;" “I really listen to my roommate when he/she talks;” and “I behave warmly toward my roommate.” We measured weekly responsiveness using the same items, asking how participants acted toward their roommate that week. Responsiveness was reliable at pretest (α =.93), posttest (α = .97) and in each weekly survey (.94 < α < .98, Mα = .97).

A parallel set of items assessed the extent to which participants believed their roommates responded to them. Pretest and posttest items asked about roommates’ general responsiveness. Sample items included “my roommate tries to make me feel comfortable about myself and how I feel;” and "my roommate tries to make me feel valued as a person." We measured weekly roommate responsiveness with the same items, referring to how roommates acted toward participants that week. Perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness was reliable at pretest (α = .95), posttest (α =.98), and in the weekly surveys (.94 < α < .98, Mα = .97).

Disclosure to the roommate and perceptions of roommates’ disclosure were measured with a 5-item modified version of a disclosure measure used by Gore and colleagues (Gore et al., 2006a; Miller, Berg, & Archer, 1983). Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which they discussed each topic with their roommates; pretest and posttest items began with the phrase, “In general, I discuss:." All items were rated on a scale from 1 (discussed not at all) to 5 (discussed fully and completely) and included “my deepest feelings;” “my worst fears;” “what I like and dislike about myself;” “my close relationships with other people;” and “things I have done which I am proud of.” We measured weekly disclosure using the same instructions and items, beginning with the phrase “This week, I discussed:.” Disclosure to roommates was reliable at pretest (α =.85), posttest (α = .94) and from week to week (.85 < α < .95, Mα = .92).

A parallel set of items assessed the extent to which participants believed their roommates self-disclosed. Pretest and posttest items began with the phrase, “In general, my roommate discusses:." Sample items included “his/her deepest feelings;” “his/her worst fears;” and “what he/she likes and dislikes about him/herself.” We measured weekly roommate disclosure with the same items, referring to the extent to which roommates self-disclosed that week. Roommate disclosure was reliable at pretest (α = .89), posttest (α =.94), and in weekly surveys (.89 < α < .95, Mα = .93).

Perceived social support availability from roommates and support made available to roommates were measured with the Multidimensional Survey of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988). Perceived availability pretest and posttest items were preceded with the stem “In general, I feel that.” Weekly items were preceded with the stem “This past week, I felt that.” Sample items included “My roommate really tried to help me” and “I could count on my roommate if things went wrong.” Perceived social support availability was reliable at pretest (α =.93), posttest (α = .96) and from week to week (.93 < α < .97, Mα = .96).

Social support made available to roommates was also measured at pretest, posttest and weekly using a parallel set of items. Sample items included “I really tried to help my roommate” and “my roommate can count on me when things go wrong.” Social support made available to roommates was reliable at pretest (α = .92), posttest (α =.95), and in weekly surveys (.86 < α < .96, Mα = .94).

Anxiety was assessed with the Speilberger State Anxiety Scale (Spielberger, Vagg, Barker, Donham, & Westberry, 1980). At pretest and posttest, participants rated their anxiety in general on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always); in the weekly surveys, they rated their anxiety over the past week on the same scale. Anxiety had high internal consistency at pretest (α =.91), posttest (α =.94), and in each of the weekly surveys (.94 < α < .95, Mα = .94).

Depression was assessed at pretest, posttest, and weekly using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Inventory (CES-D; Radloff, 1997). The CES-D was developed to measure depressive symptoms in community samples and consists of 20 depression-related symptom items rated on a 4 point scale (0–3) based on the amount of time during the past week the respondent has experienced each symptom. Scores can range from 0 to 60. The CES-D had high internal consistency at pretest (α =.86), posttest (α =.89) and each of the weekly surveys (.90 < α < .92, Mα = .91).

Results

Factor Analyses

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and intrapersonal (i.e., within-person) intraclass correlations, which adjust for the degree of nonindependence between dyad members (Griffin & Gonzalez, 1995) for all primary variables in Study 1. Because correlations between compassionate goals and responsiveness to roommates and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness were high, we conducted exploratory factor analyses (EFA) on these items at pretest and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) on items at posttest and each week, comparing the fit of a model specifying 2 factors with a model specifying 1 factor.

Table 1.

Study 1 means, standard deviations, and intrapersonal intraclass correlations for all primary pretest, posttest, and mean weekly variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. |

M (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pretest Compassionate Goals |

4.04 (.50) |

|||||||||||

| 2. Pretest Self-Image Goals |

−.22*** | 2.53 (.68) |

||||||||||

| 3. Pretest Responsiveness to Roommates |

.56*** | −.28*** | 4.37 (.61) |

|||||||||

| 4. Pretest Perceptions of Roommates’ Responsiveness |

.47*** | −.30*** | .62*** | 4.17 (.74) |

||||||||

| 5. Posttest Compassionate Goals |

.49*** | −.17* | .42*** | .38*** | 3.89 (.82) |

|||||||

| 6. Posttest Self-Image Goals |

−.02 | .54*** | −.13 | −.20** | −.14* | 2.36 (.77) |

||||||

| 7. Posttest Responsiveness to Roommates |

.35*** | −.18** | .38*** | .38*** | .84*** | −.20** | 4.16 (.85) |

|||||

| 8. Posttest Perceptions of Roommates’ Responsiveness |

.24*** | −.11 | .29*** | .42*** | .67*** | −.19** | .79*** | 3.99 (.97) |

||||

| 9. Chronic Compassionate Goals |

.69*** | −.24*** | .54*** | .50*** | .84*** | −.11 | .70*** | .55*** | 3.87 (.61) |

|||

| 10. Chronic Self- Image goals |

−.14* | .68*** | −.20** | −.23*** | −.21** | .88*** | −.23*** | −.21** | −.23*** | 2.38 (.67) |

||

| 11. Chronic Responsiveness to oommates |

.51*** | −.28*** | .57*** | .57*** | .75*** | −.20** | .75*** | .70*** | .82*** | −.30*** | 4.03 (.70) |

|

| 12. Chronic Perceptions of Roommates’ Responsiveness |

.41*** | −.26*** | .47*** | .65*** | .65*** | −.24*** | .69*** | .81*** | .71*** | −.30*** | .86*** | 3.92 (.81) |

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

N = 230 at pretest, N = 218 at posttest. Chronic scores were calculated by averaging across the weekly reports. Self-image and compassionate goals were measured on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Responsiveness to roommates and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness were measured on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Compassionate goals and responsiveness to roommates

Compassionate goals and responsiveness to roommates, though correlated, are empirically distinct. EFAs on the pretest items suggested that 2 factors accounted for 48% of the variance: all responsiveness items loaded on the first factor, with loadings ranging between .64 and .99; all compassionate goal items loaded on the second factor, with loadings ranging between .38 and .66. Importantly, no secondary loading exceeded |.28|. We conducted CFAs on items at posttest and each of the 10 weeks (yielding 11 separate sets of CFAs), testing two-factor, 136.84 < χ2 (76, 218 < N < 230) < 232.48, Mχ2(76, 218 < N < 230) = 183.77, and single-factor solutions, 336.77 < χ2(77, 218 <N < 230) < 726.72, Mχ2(77, 218 < N < 230) = 586.71. For all analyses, two-factor solutions provided significantly better fit, 194.33 < Δχ2(1, 218 < N < 230) < 554.95, MΔχ2(1, 218 < N < 230) = 402.94.

Compassionate goals and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness

Compassionate goals and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness, though correlated, are also empirically distinct. EFAs on the pretest items suggested that 2 factors accounted for 51% of the variance: all responsiveness items loaded on the first factor, with loadings ranging between .74 and .93; all compassionate goal items loaded on the second factor, with loadings ranging between .39 and .63. Importantly, no secondary loading exceeded |.23|. We conducted CFAs on items at posttest and each of the 10 weeks (again, yielding 11 separate sets of CFAs), testing two-factor, 110.55 < χ2(76, 218 < N < 230) < 247.82, Mχ2(76, 218 < N < 230) = 166.94, and single-factor solutions, 448.56 < χ2(76, 218 < N < 230) < 948.77, Mχ2(76, 218 < N < 230) = 753.14. For all analyses, two-factor solutions provided significantly better fit, 338.01 < Δχ2(1, 218 < N < 230) < 747.22, MΔχ2(1, 218 < N < 230) = 586.20.

Overview of Primary Analyses

We conducted data analyses in two phases. In Phase 1 we focused on the intrapersonal associations between goals and responsiveness. We hypothesized that students’ goals would predict change in their responsiveness to roommates (Path A; Figure 1), which would predict change in their perceptions of their roommates’ responsiveness (Path B), which would in turn, predict change in their compassionate and self-image goals (Path D). In Phase 2 we focused on the interpersonal associations among these variables to examine how actors’ goals predict change in their responsiveness to partners (Path A), which predicts change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness (Path F), which predicts change in partners’ subsequent responsiveness to actors (Path I) and goals (Path J). We tested both the intra- and interpersonal associations 1) within weeks, 2) from week to week using lagged analyses, and 3) across the semester from pretest to posttest.

Importantly, all intra- and interpersonal analyses assess change. For example, in weekly analyses we test whether fluctuations in goals (i.e., the difference between goals that week and that person’s average goals across 10 weeks) predict responsiveness that week; in lagged analyses, we test whether Week 1 goals predict change in responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2; and in pretest and posttest analyses, we test whether chronic goals predict change in responsiveness from pretest to posttest. Thus, these analyses test the dynamic intra- and interpersonal associations between goals, responsiveness, and perceptions of others’ responsiveness.

General Analytic Strategy

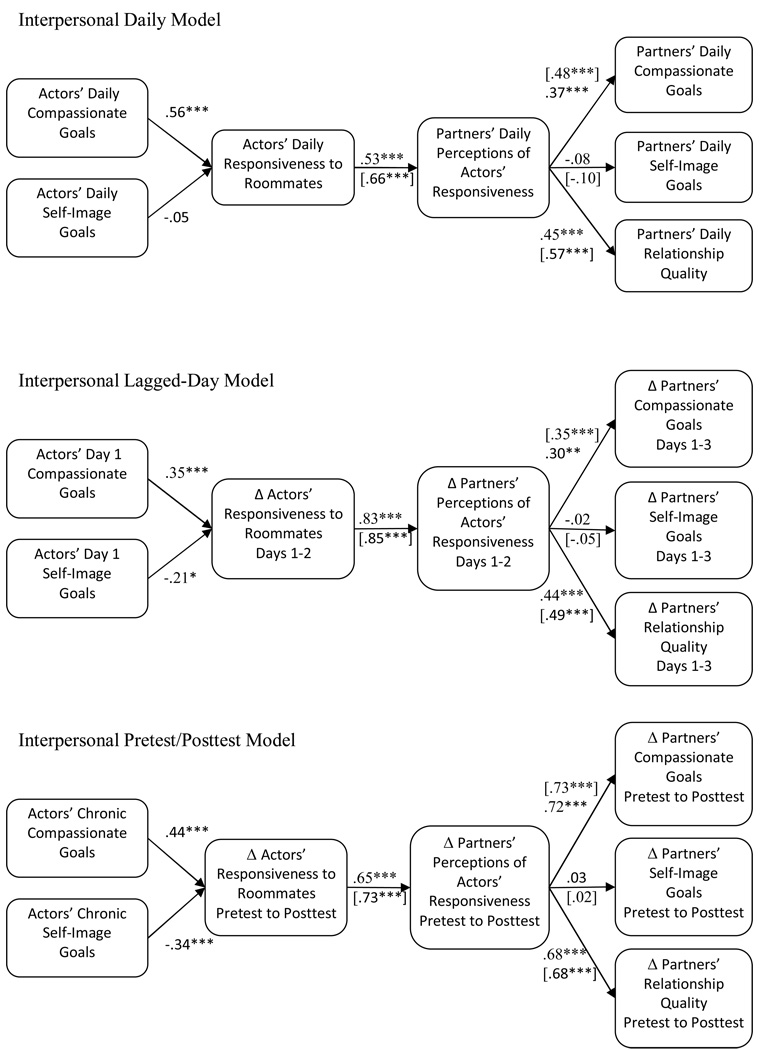

In these data, individuals were nested within dyads and dyads were crossed with weeks (Kashy, Donnellan, Burt, & McGue, 2008). Thus, we controlled for the nonindependence of individuals within dyads in all analyses using the MIXED command in SPSS (Campbell & Kashy, 2002; Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), and because individuals within dyads were indistinguishable, we specified compound symmetry so that intercept variances between dyad members were equal. For all analyses, we structured the data so that each dyad was represented by two lines of data, allowing each participant within a dyad to represent both an actor and a partner (see Campbell & Kashy, 2002, for a sample arrangement of data). Path models were tested sequentially, with a separate regression equation for each path. For each path, we regressed the criterion on the predictor(s), controlling for all variables preceding that path in the model. All Study 1 path analyses are illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Estimates outside of brackets indicate the partial correlation for that association, controlling for previous paths in the model; estimates inside brackets indicate tests of the individual path, not controlling for previous paths in the model. Partial correlations for all analyses were calculated using the method described by Rosenthal and Rosnow (1991).

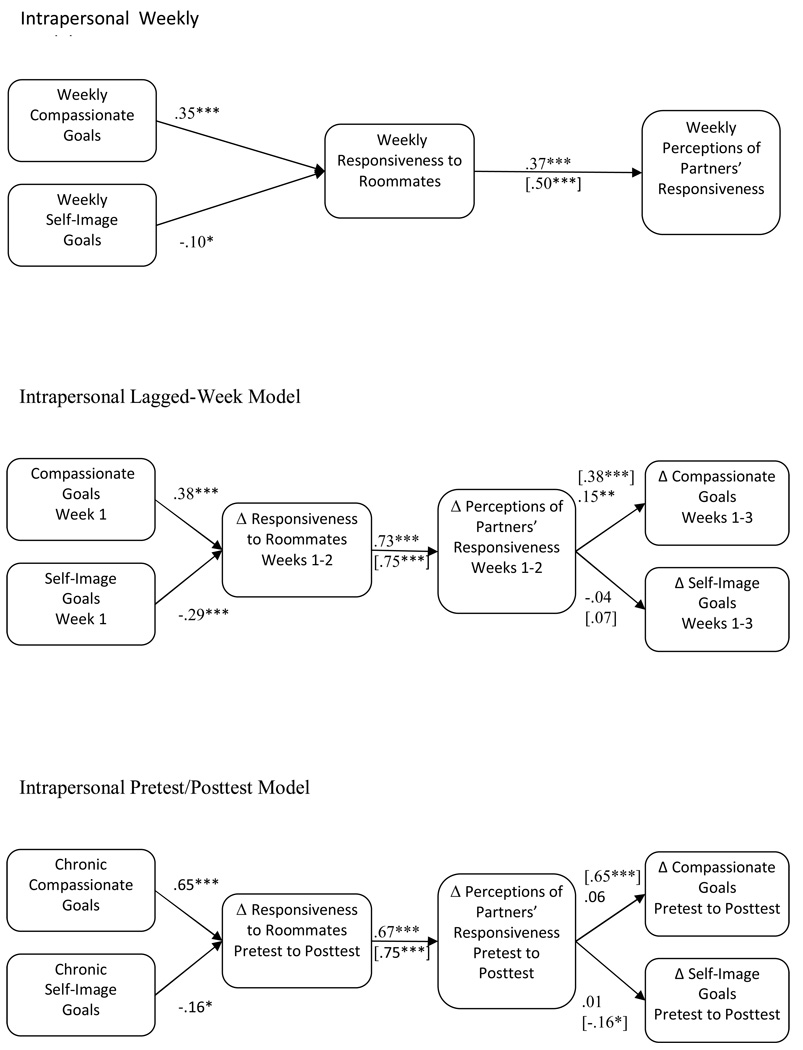

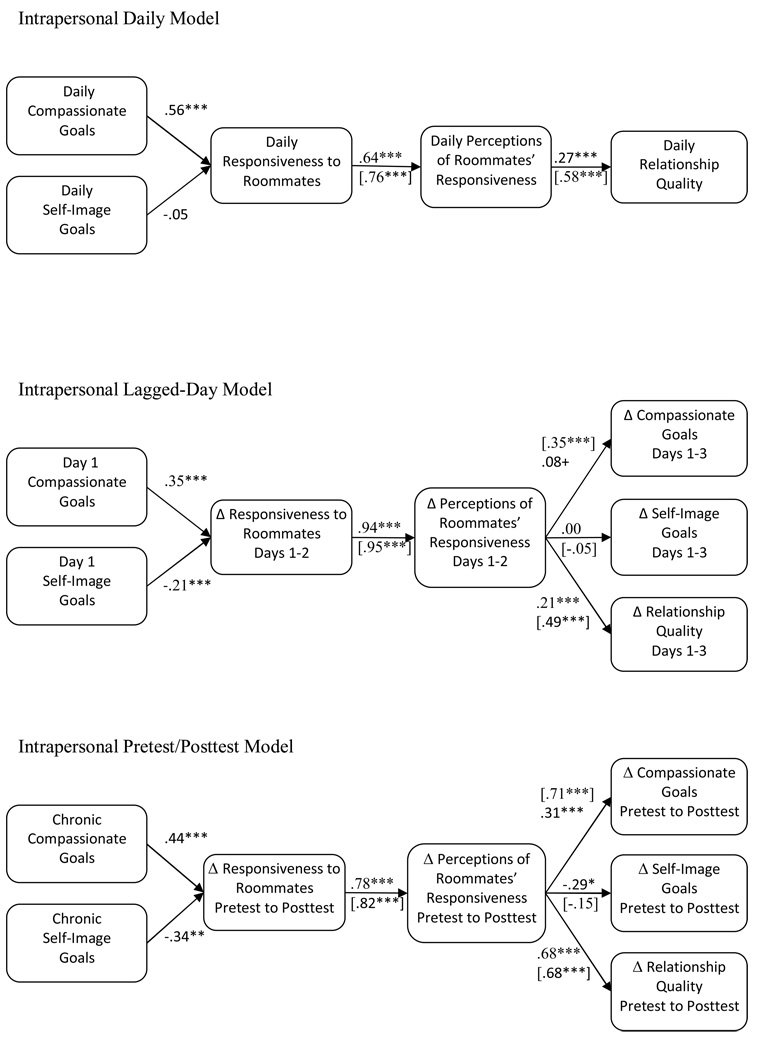

Figure 2.

Study 1: Intrapersonal (within-person) path analyses of weekly, lagged-week, and pretest and posttest data. NOTE: All estimates are partial correlations; estimates in brackets indicate test of the individual path, not controlling for previous paths in the model. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05.

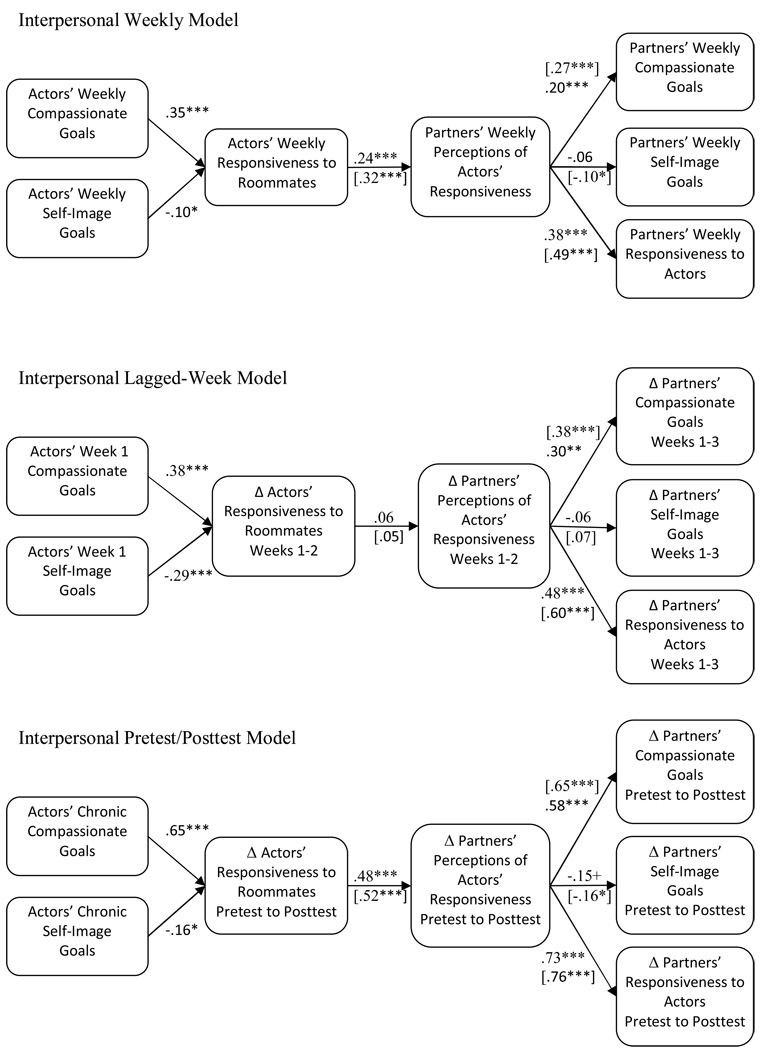

Figure 3.

Study 1: Interpersonal (between-person) path analyses of weekly, lagged-week, and pretest and posttest data. NOTE: All estimates are partial correlations; estimates in brackets indicate test of the individual path, not controlling for previous paths in the model. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05.

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and intrapersonal (i.e., within-person) intraclass correlations (Griffin & Gonzalez, 1995), for all primary pretest, posttest, and chronic weekly variables. We created measures of chronic compassionate and self-image goals by averaging each measure across the 10 weeks. In general, compassionate goals, responsiveness, and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness were strongly correlated at pretest and posttest, and across weeks. Self-image goals were less strongly associated with responsiveness and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness. Because compassionate and self-image goals were significantly correlated, we regressed all outcome variables on compassionate and self-image goals simultaneously. Table 2 shows the interpersonal (i.e. actor-partner) intraclass correlations for all primary variables. Roommates’ compassionate goals, responsiveness and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness were moderately correlated across time-points; self-image goals predicted fewer partner variables.

Table 2.

Study 1 interpersonal (i.e. actor-partner) intraclass correlations for all pretest, posttest, and mean weekly variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pretest Compassionate Goals | .24* | |||||||||||

| 2. Pretest Self-Image Goals | −.11 | .02 | ||||||||||

| 3. Pretest Responsiveness to Roommates | .20** | −.08 | .13 | |||||||||

| 4. Pretest Perceptions of Roommates’ Responsiveness. |

.25*** | −.11 | .22** | .25** | ||||||||

| 5. Posttest Compassionate Goals | .13 | −.05 | .10 | .18* | .22* | |||||||

| 6. Posttest Self-Image Goals | −.08 | −.01 | −.14* | −.07 | −.09 | .07 | ||||||

| 7. Posttest Responsiveness to Roommates . |

.06 | −.03 | .10 | .18* | .22* | −.10 | .32*** | |||||

| 8. Posttest Perceptions of Roommates’ Responsiveness . |

.02 | .02 | .03 | .14 | .22** | −.10 | .28** | .34*** | ||||

| 9. Chronic Compassionate Goals | .23** | −.10 | .19* | .26*** | .20* | −.14* | .20* | .17* | .30** | |||

| 10. Chronic Self-Image goals | −.10 | .01 | −.09 | −.09 | −.11 | .04 | −.10 | −.08 | −.12 | .00 | ||

| 11. Chronic Responsiveness to Roommates . |

.21** | −.13 | .15 | .26*** | .24** | −.19** | .25** | .21* | .33*** | −.16* | .33*** | |

| 12. Chronic Perceptions of Roommates’ Responsiveness |

.15* | −.07 | .14 | .27*** | .23** | −.14* | .26** | .29** | .30*** | −.12 | .35*** | .43*** |

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05.

N = 230 at pretest, N = 218 at posttest. Chronic scores were calculated by averaging across the weekly reports. Self-image and compassionate goals were measured on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Responsiveness to roommates and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness were measured on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Intrapersonal Processes: Students’ Goals Predicting Their Own Responsiveness and Subsequent Goals

Phase 1 analyses test an intrapersonal model in which students’ compassionate and self-image goals predict change in their responsiveness to roommates (Path A; Figure 1), which predicts change in their perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness (Path B), which in turn predicts change in students’ subsequent compassionate and self-image goals (Path D). Thus, all Phase 1 analyses use only actor variables as predictors and outcomes. Note that, because the data are structured so that actors and partners are interchangeable, these analyses simultaneously test the process by which partners’ goals lead to partners’ own responsiveness and goals (i.e., Paths G, H, and J).

Weekly associations

First, we examined our hypothesized model within weeks, testing whether weekly interpersonal goals predicted responsiveness to roommates that same week, which then predicted perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness that week. Coefficients for weekly analyses were derived from random-coefficients models using restricted maximum-likelihood estimation, and models included fixed and random effects for the intercept and each predictor. In weekly analyses we person-centered all predictors so that scores represent differences from each individual’s own average across 10 weeks (e.g., Enders & Tofighi, 2007; Kreft & de Leeuw, 1998; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Path analyses supported our hypothesized model within weeks (see the top of Figure 2). Weekly compassionate goals predicted higher and self-image goals predicted lower weekly responsiveness to roommates. Responsiveness to roommates, in turn, positively predicted higher perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness.

Lagged-week analyses

Next, we tested the lagged-week associations between interpersonal goals, responsiveness to roommates, and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness. Examination of the temporal sequence of effects across weeks does not demonstrate causality but can shed light on the plausibility or implausibility of causal pathways (Kenny, 1975; Leary, 1995; Rogosa, 1980; West, Biesanz, & Pitts, 2000). For example, evidence that compassionate goals on Week 1 predict responsiveness in Week 2, controlling for responsiveness on Weeks 1 (i.e., testing whether goals one week predict residual change in responsiveness the following week) would be consistent with the hypothesis that compassionate goals cause responsiveness. No association would rule out a causal effect over this time period. Thus, unlike within-week analyses, lagged analyses test the plausibility of causal associations for each hypothesized pathway in our intrapersonal model.

Coefficients for lagged-week analyses were derived from random-coefficients models using restricted maximum-likelihood estimation, with models including fixed and random effects for the intercept and each predictor. We used a residual change strategy to test changes from week to week, regressing the Week N + 1 dependent variable on relevant Week N predictors, controlling for the Week N dependent variable. When change in a variable was a predictor, we entered the Week N and Week N + 1 predictors into the model and interpreted the week N + 1 variable.

We grand mean centered predictors in tests of lagged-week hypotheses because our prediction concerned change in the outcome from week to week. Lagged analyses examine whether change in the outcome from one week to the next is related to levels of the goal (or other predictor), regardless of the source – individual differences or weekly fluctuations around those individual differences. For example, we hypothesize that As’ goals one week predict their responsiveness the following week, controlling for that week’s responsiveness. Person centering predictors tests whether fluctuations in As’ goals from As’ own average goals predict outcomes. Consequently, in our example person-centering predictors in lagged analyses tests whether within-person departures from As’ average goals one week predict As’ responsiveness the following week, controlling for within-person departures from As’ average responsiveness that week. This does not test our lagged hypothesis. Thus, centering on the grand mean for that week is justified and appropriate in these analyses (e.g., Enders & Tofighi, 2007).4

In the lagged-week data, we tested a path model in which goals at Week 1 predict change in responsiveness to roommates from Weeks 1 to 2, which predict simultaneous change in perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2, which in turn predict change in compassionate and self-image goals from Weeks 1 to 3. We expected that, in the case of projection, associations between changes in responsiveness to roommates and changes in perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness would be relatively immediate because they occur as a function of perceptions – we expect that when actors become more responsive to roommates, they simultaneously increase their perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness. Accordingly, we hypothesized that change in responsiveness to roommates from Weeks 1 to 2 predicted simultaneous change in perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness.

For each path, we regressed the criterion on the predictor(s), controlling for all variables preceding that path in the model. We tested this path model (i.e., actors’ Week N compassionate and self-image goals predict change in actors’ responsiveness to roommates from Weeks N to N + 1, which predicts change in actors’ perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness from Weeks N to N + 1, which predicts change in actors compassionate and self-image goals from weeks N to N + 2; see the middle of Figure 2) in 4 regression equations (except when goals were entered as predictors: because we tested them simultaneously, we were able to test two paths in one equation). Lagged analyses were conducted on all 10 weeks. For simplicity, we refer to Week N as “Week 1,” Week N+1 as “Week 2,” and Week N+2 as “Week 3.”

Lagged-week path analyses supported our hypotheses (see middle of Figure 2). Week 1 compassionate goals predicted increased and Week 1 self-image goals predicted decreased responsiveness to roommates from Weeks 1 to 2, which predicted increased perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2, which predicted increased compassionate goals and decreased self-image goals from Weeks 1 to 3.

Change across the semester

To test whether and how students’ chronic compassionate and self-image goals contribute to long-term changes in their responsiveness, perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness and goals, we examined a path model in which chronic goals averaged across 10 weeks predicted change in responsiveness to roommates across the semester, which then predicted change in perceptions of the roommates’ responsiveness, which in turn predicted changes in goals from pretest to posttest.

Coefficients for testing change from pretest to posttest were derived from fixed-effects models using restricted maximum-likelihood estimation. We grand mean centered predictors in tests of pretest and posttest hypotheses because we were interested in chronic goals and responsiveness as individual differences. We used a residual change strategy, similar to that used in lagged-week analyses, to test changes from pretest to posttest.

Results partially support our path model (see bottom of Figure 2). Chronic compassionate goals predicted increased and chronic self-image goals predicted decreased responsiveness to roommates from pretest to posttest, which predicted change in perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness from pretest to posttest, but perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness did not predict changes in students’ own compassionate and self-image goals from pretest to posttest.

Next, we tested several alternative explanations for and moderators of the associations tested in Figure 2. We tested whether perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness, disclosure, support, anxiety and depression explained associations in our models by adding the appropriate variables to the path models tested above. Specific analyses for each covariate are described below. Note that our main concern was not whether these covariates were related to each outcome, but whether they could explain or offer an alternative explanation for our findings. Thus we do not report the association between each covariate and outcome variable. Instead, we report associations between our main predictors and outcome variables, controlling for covariates. We also test whether associations in Figure 2 are moderated by anxiety, depression or gender by adding the appropriate main effect and product terms, as described below. Simple slopes for interactions were computed at 1 standard deviation above and below the means of the moderators (Aiken & West, 1991). Because of space considerations, we do not report individual statistics for each covariate test. Instead, we report a summary of results for each covariate; tables of results can be obtained from the first author.

Do perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness explain associations between goals and change in responsiveness to roommates?

Associations between students’ interpersonal goals and changes in their responsiveness to roommates might be attributed to perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness: students’ goals may lead them to be more or less responsiveness to roommates because goals are also associated with perceiving roommates as more or less responsive. We retested the links between compassionate and self-image goals and responsiveness to roommates in all models in Figure 2, controlling for weekly perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness in weekly analyses, Week 1 perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness in lagged analyses, and chronic perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness in the pretest and posttest analyses. Across all three sets of analyses, all associations between compassionate goals and higher or increased responsiveness remained significant, .17 < prs < .46, all ps < .001, although perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness predicted higher or increased responsiveness to roommates, .37 < prs < .40, all ps < .001, across analyses. Thus, students’ perceptions of roommates as more or less responsive do not explain the association between compassionate goals and increased responsiveness to roommates.

On the other hand, 2 of the 3 analyses suggested that associations between students’ self-image goals and lower or decreased responsiveness to roommates could be explained by perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness. Weekly self-image goals no longer predicted weekly responsiveness to roommates, pr = −.03, ns, and chronic self-image goals no longer predicted change in responsiveness from pretest to posttest, pr = −.09, ns. In lagged analyses, Week 1 self-image goals still predicted decreased responsiveness to roommates from Weeks 1 to 2, pr = −.25, p < .001. Thus, students’ self-image goals led to their decreased responsiveness to the extent that they perceived their roommates as less responsive.

Does disclosure explain these associations?

Because others’ disclosure elicits responsiveness and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness may be a function of people’s own disclosure (Reis & Shaver, 1988), we examined the possibility that associations between responsiveness to roommates and perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness could be explained by perceptions of roommates’ disclosure or disclosure to roommates. We reanalyzed paths in the weekly, lagged-week, and change from pretest to posttest analyses, controlling for the appropriate disclosure variable (i.e., we regressed responsiveness to roommates on goals controlling for perceptions of roommates’ disclosure and we regressed perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness on responsiveness to roommates controlling for disclosure to roommates). In lagged-week analyses we controlled for Week 1 disclosure, or Weeks 1 and 2 disclosure, depending on the specific path we tested. In testing change from pretest to posttest, we controlled for the appropriate chronic or pretest and posttest disclosure variables, again depending on the specific path we tested.

Interpersonal goals predicted responsiveness and responsiveness predicted perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness, independent of disclosure. In 9 of 10 analyses, results remained unchanged when we retested these paths controlling for the appropriate disclosure variables; in the weekly model, the association between weekly self-image goals and responsiveness to roommates became marginally significant when we controlled for perceptions of roommates’ disclosure that week, pr = −.07, p < .06. Thus, people’s interpersonal goals offer an alternative to disclosure in creating responsive close relationships.

Does support availability explain these associations?

These paths might be explained by perceived available support from roommates and support made available to roommates. We reanalyzed all paths, controlling for the appropriate support variable (i.e., when responsiveness to roommates was the criterion, we controlled for support made available to roommates; when perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness or goals were the criterion, we controlled for perceived available support from roommates), using the strategy described above (e.g., in lagged-week analyses we controlled for change in support on the weeks responsiveness variables were included in analyses).

Results remained unchanged when we retested individual paths controlling for the appropriate support variables in 8 of 10 analyses (we did not retest nonsignificant links between perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness and goals). In the weekly model, the association between self-image goals and responsiveness to roommates became nonsignificant when we controlled for perceived available support, pr = −.05, ns, and in the pretest to posttest model, the association between chronic self-image goals and change in responsiveness to roommates became nonsignificant when we controlled for chronic perceived available support, pr = −.09, ns. Thus, self-image goals do not predict change in responsiveness beyond available support: that is, self-image goals may contribute to change in responsiveness because of available support. However, available support cannot explain associations between compassionate goals and change in responsiveness, and support made available to roommates cannot explain the association between students’ responsiveness and their perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness, nor can it explain why students’ perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness predict change in their compassionate goals in the lagged analyses.

Does anxiety or depression explain associations in these models?

We also tested whether the associations in Figure 2 were explained by feeling anxious or depressed. We reanalyzed all paths in weekly, lagged-week, and change from pretest to posttest analyses, controlling for anxiety and depression in separate analyses, using the strategy for testing covariates described above. Results did not change when we controlled for anxiety and depression in 18 of 20 analyses. In the pretest and posttest model, the link between chronic self-image goals and change in responsiveness to roommates became nonsignificant when we controlled for chronic anxiety, pr = −.13, ns, and marginal when we controlled for chronic depression, pr = −.14, p = .07. Thus, anxiety and depression appear to explain why self-image goals lead to longer-term decreases in responsiveness, but they cannot explain why self-image goals lead to decreased responsiveness in weekly and lagged-week analyses, or why compassionate goals lead to higher and increased responsiveness. Anxiety and depression also cannot explain projection of responsiveness or why it leads to increased compassionate goals in the lagged model.

Do associations in these models differ by levels of anxiety or depression?

Because links in the intrapersonal model might depend on negative mood, we tested whether anxiety or depression moderated the simple associations in Figure 2 (i.e., not controlling for other variables in the model), testing 26 separate product terms. Only one was significant: in the weekly model (top of Figure 2) anxiety moderated the relation between weekly compassionate goals and weekly responsiveness to roommates, pr = .07, p <.05, such that this association was stronger for those who reported higher anxiety, pr = .33, p <.001, compared to those reporting lower anxiety, pr = .20, p <.001. Results suggested that compassionate goals are beneficial for responsiveness, particularly when anxiety is higher. No other links in the intrapersonal models were moderated by anxiety or depression (all other prs < |.13|, ns). Thus, results strongly suggest that the processes described by the intrapersonal model do not operate differently depending on negative mood.

Do these associations differ by gender?

Because the intrapersonal process from goals to perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness and change in goals might differ for men and women, we tested whether gender moderated each individual path (i.e., not controlling for other variables in the models) in all models in Figure 2. In all analyses, gender was treated as a fixed effect (i.e., no random effects were specified in weekly and lagged-week models) and coded such that 1 = men and 2 = women. Gender moderated just 2 of the 13 associations tested (all other prs < |.07|, ns). First, in the lagged model (the middle of Figure 2), gender moderated the association between change in responsiveness to roommates and change in perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness, pr = .25, p < .001, such that the relation was stronger for women, pr = .75, p < .001, than men, pr = .48, p < .001. Second, in tests of pretest to posttest change (the bottom of Figure 2), gender moderated the association between change in perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness and change in self-image goals, pr = −.16, p < .05, such that perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness predicted decreased self-image goals for women, pr = −.20, p < .01, but not men, pr = .04, ns.

Summary of intrapersonal processes

These data support our hypothesis that interpersonal goals predict change in responsiveness, which leads to projection of responsiveness: compassionate goals predict increased and self-image goals predict decreased responsiveness to roommates, which predicts increased perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness. This process operates within weeks, from week to week, and across 10 weeks, supporting our hypothesis about the dynamic associations between goals and projection of responsiveness.5. Covariates did not consistently account for any of these associations, nor were associations moderated by negative mood or gender.6

Results were mixed with respect to our hypothesis that the relation between goals and projection is self-perpetuating. Lagged-week analyses supported our hypothesis - increased perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2 predicted changes in interpersonal goals from Weeks 1 to 3. However, analyses of change from pretest to posttest did not support this hypothesis – changes in perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness from pretest to posttest did not predict changes in goals from pretest to posttest.

Interpersonal Processes: Actors’ Goals and Responsiveness Predicting Partners’ Goals and Responsiveness

The goal of Phase 2 analyses was to test our interpersonal model whereby actors’ compassionate goals predict their increased and self-image goals predict their decreased responsiveness to partners (Path A; Figure 1). Actors’ responsiveness to partners then predicts partners’ increased perceptions of actors’ responsiveness (Path F), which then predicts partners’ increased responsiveness to actors (Path I) and increased compassionate and decreased self-image goals (Path J). Again, note that, because the data are structured so that actors and partners are interchangeable, these analyses simultaneously the process by which partners’ goals predict actors’ responsiveness and goals (i.e., Paths G, L, C, and D). We examined this general model within weeks, from week to week using lagged analyses, and the across the semester using the same analytic strategies described to test our projection (i.e., intrapersonal) hypotheses.

Weekly Associations

We examined our hypothesized interpersonal model within weeks, testing whether actors’ weekly interpersonal goals predicted their responsiveness to roommates that same week, which then predicted partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness that week, which then predicted partners’ interpersonal goals and responsiveness to actors.

Within-week analyses support our hypotheses (see the top of Figure 3). On weeks when actors had higher compassionate goals they reported being more responsive to partners, and on weeks when actors had higher self-image goals they reported being less responsive to partners. Actors’ responsiveness to partners predicted partners’ higher perceptions of actors’ responsiveness, which predicts partners’ higher responsiveness to actors and partners’ compassionate goals. Partners’ weekly perceptions of actors’ responsiveness did not predict their own self-image goals that same week.

Lagged-week analyses

Again, because lagged analyses provide information about the plausibility of causal pathways, we tested whether actors’ compassionate and self-image goals at Week 1 predicted change in their responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2, which predicted simultaneous change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2, which then predicted change in partners’ interpersonal goals and responsiveness to actors from Weeks 1 to 3. We predicted that change in actors’ responsiveness to roommates from Weeks 1 to 2 predicted simultaneous change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2 because responsiveness transactions between roommates should occur simultaneously (i.e., partners should perceive change in actors’ responsiveness as actors report change in their own responsiveness).

Lagged-week analyses did not support our interpersonal hypotheses (see middle of Figure 3). Actors’ Week 1 compassionate goals predicted increased responsiveness and Week 1 self-image goals predicted decreased responsiveness to partners from Weeks 1 to 2, but change in actors’ responsiveness to partners from Weeks 1 to 2 did not predict simultaneous change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2. Change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2 positively predicted change in partners’ responsiveness to actors and compassionate goals from Weeks 1 to 3, but did not predict change in partners’ self-image goals from Weeks 1 to 3.

These results do not support the plausibility of causal effects of change in actors’ responsiveness to partners on change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness. However, changes in partners’ perceptions of actor’s responsiveness led to their increased responsiveness to actors and compassionate goals the following week.

Change from pretest to posttest

To test whether and how actors’ chronic compassionate and self-image goals contribute to long-term changes in their own responsiveness, and partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness, responsiveness to actors, and goals, we examined a path model in which actors’ chronic goals predicted change in actors’ responsiveness to partners across the semester, which predicted change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness, which in turn predicted changes in partners’ goals and responsiveness to actors from pretest to posttest.

Results support our interpersonal model (see bottom of Figure 3). Actors’ chronic compassionate goals predict increased and chronic self-image goals predict decreased responsiveness to partners. Change in actors’ responsiveness to partners positively predicted change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness from pretest to posttest, which positively predicted change in partners’ responsiveness to actors and compassionate goals and marginally negatively predicted change in partners’ self-image goals across the semester.

Next, we tested several alternative explanations for and moderators of the associations tested in Figure 3. We tested whether disclosure, available support, anxiety or depression explained associations between actors’ responsiveness to partners and partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness by adding the appropriate variables to the interpersonal path models tested above. Details of these analyses are provided below. Note that, as in tests of covariates in the intrapersonal models, the critical test was whether covariates altered the results of our path models, and not whether the covariates were related to each outcome. Because of this, we do not report the association between each covariate and outcome variable. We also tested whether associations between actors’ responsiveness and partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness were moderated by partners’ own goals, and whether associations unique to the interpersonal models were moderated by anxiety, depression or gender using the strategy described above. Again, because of space considerations, we do not report individual statistics for each covariate test, but instead report a summary of results for each covariate; tables of results can be obtained from the first author.

Do partners’ goals influence how they perceive actors’ responsiveness?

We tested the possibility that the links between actors’ responsiveness and partners’ increased perceptions of actors’ responsiveness were dependent on partners’ goals. For all models in Figure 3, we tested whether partners’ goals moderated the individual paths (i.e., not controlling for other variables in the models) between actors’ responsiveness to partners and partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness, testing the moderating effect of each goal separately. In the weekly model we tested whether partners’ weekly goals moderated this association; in the lagged analyses we tested whether partners’ Week 2 goals moderated the link between change in actors’ responsiveness to partners from Weeks 1 to 2 and change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness from Weeks 1 to 2; in the pretest to posttest analyses we tested whether partners’ posttest goals moderated the link between change in actors’ responsiveness to partners from pretest to posttest and change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness from pretest to posttest. Across analyses, partners’ goals did not moderate this association, compassionate goals: −.07 < pr < .02, all ns; self-image goals: all prs < .02, all ns. Actors’ and partners’ agreement about actors’ responsiveness to partners does not depend on partners’ compassionate or self-image goals.

Does disclosure, available support, anxiety, or depression explain associations between actors’ responsiveness to partners and partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness?7

We tested associations between actors’ responsiveness to partners and partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness in weekly and change from pretest to posttest models in Figure 3, separately controlling for partners’ perceptions of actors’ disclosure, partners’ social support available from actors, and partners’ anxiety and depression using a strategy similar to that described for the intrapersonal models. We did not test covariates in the lagged model because there was no association between change in actors’ responsiveness and change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness. Results remained unchanged in 7 of 8 tests. Change in actors’ responsiveness to partners from pretest to posttest no longer predicted change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness from pretest to posttest when we controlled for change in partners’ support available from actors. Overall, results suggest that actors’ and partners’ agreement about actors’ responsiveness cannot be accounted for by partners’ perceptions of disclosure, anxiety, or depression. However, changes in actors’ responsiveness to partners leads to changes in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness because actors’ responsiveness is supportive.

Does disclosure, available support, anxiety or depression explain associations between changes in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness and change in partners’ responsiveness or compassionate goals?

We tested the link from partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness to partners’ responsiveness and compassionate goals, controlling for partners’ perceptions of actors’ disclosure, support available from roommates, anxiety, and depression (in 24 separate analyses). We did not retest nonsignificant links between partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness and partners’ self-image goals. All results remained unchanged, suggesting that partners’ responsiveness reciprocity (i.e., the link between partners’ perceptions of responsiveness and responsiveness to actors) and compassionate goals could not be accounted for by their perceptions of actors’ disclosure, support available from roommates, anxiety, or depression.

Do these associations differ by partners’ levels of anxiety or depression?

We tested whether partners’ anxiety or depression moderated links between actors’ responsiveness and partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness in all models in Figure 3. We also tested whether partner’s anxiety or depression moderated associations between partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness and partners’ responsiveness to actors in lagged and pretest and posttest models. Partners’ anxiety and depression did not moderate these associations in 9 of 10 tests (all prs < |.11|, ns). However, in pretest and posttest analyses, depression moderated the link between change in partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness and partners’ responsiveness, pr = −.20, p < .01, such that this association was stronger when partners also reported lower depression (lower depression: pr = .70, p < .001; higher depression: pr = .63, p < .001). Thus, when partners become more depressed, they are less likely to reciprocate increased perceptions of actors’ responsiveness.

Do these associations differ by gender?

We tested whether gender moderated associations unique to the interpersonal models (e.g., links between actors’ responsiveness to partners and partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness in weekly, lagged-week, and change from pretest to posttest analyses; links between partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness and partners’ goals in weekly analyses; and links between partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness and partners’ responsiveness to actors in lagged-week, and change from pretest to posttest analyses), using the same strategy reported for testing whether gender moderated intrapersonal associations. Gender did not moderate any of the 7 paths tested (all prs < |.13|, all ns).

Discussion

Study 1 examined intra- and interpersonal models of responsiveness in first-semester college roommates. Results were generally consistent with our hypotheses: students’ compassionate and self-image goals lead to change in their responsiveness to roommates, with consequences for change in both people’s perceptions of responsiveness in the relationship and interpersonal goals. Thus, people’s goals can create their own and others’ responsiveness and goals. In general, these associations were not due to disclosure, available support, anxiety, or depression.

Students’ goals predict their own experiences of responsiveness - their compassionate and self-image goals predict change in their responsiveness to partners, which then predicts projection of their responsiveness onto partners. We also predicted a self-perpetuating cycle between goals and responsiveness in relationships: actors’ perceptions of roommates’ responsiveness in turn predict change in their own compassionate and self-image goals. We found support for this hypothesis in the lagged-week data, but these effects did not appear to have any cumulative effect from pretest to posttest, suggesting projection processes have relatively short-term consequences for people’s goals, but do not affect their goals over the longer-term.

Tests of the interpersonal associations were partially consistent with our hypothesis. We expected agreement between actors and partners on actors’ responsiveness to partners, which should have predicted change in partners’ responsiveness to actors and goals. We found strong evidence for this hypothesis within weeks and over the semester - when actors reported increased responsiveness to partners, partners perceived increased responsiveness from actors, which then led to partners’ increased responsiveness to actors and increased compassionate goals. However, we did not find these associations in the lagged-week analyses – changes in actors’ responsiveness to partners from Weeks 1 to 2 did not predict partners’ perceptions of actors’ responsiveness over that same period, perhaps due to measurement timing; when students were asked to think about their and their roommates’ behaviors over the past week, the two roommates may have simply recalled or drew their responses from different events. More precise measurements of daily goals and responsiveness might show greater agreement between actors’ and partners’ reports. In study 2, we examined these associations in daily measures across three weeks to investigate this possibility.

Study 1 also did not address the implications of being responsive to others for the relationship itself. We predicted that this process of building (or undermining) projected and actual responsiveness between roommates has implications for both people’s perceived relationship quality. We included a measure of relationship quality in Study 2 to address this issue.