Abstract

Using data from a 6-year longitudinal follow-up sample of 240 youth who participated in a randomized experimental trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families with children ages 9 -12, the current study tested mechanisms by which the intervention reduced substance use and risky sexual behavior in mid to late adolescence (15–19 years old). Mechanisms tested included parental monitoring, adaptive coping, and negative errors. Parental monitoring at 6-year follow-up mediated program effects to reduce alcohol and marijuana use, polydrug use, and other drug use for those with high pre-test risk for maladjustment. In the condition that included a program for mothers only, increases in youth adaptive coping at 6-year follow-up mediated program effects on risky sexual behavior for those with high pre-test risk for maladjustment. Contrary to expectation, program participation increased negative errors and decreased adaptive coping among low risk youth in some of the analyses. Ways in which this study furthers our understanding of pathways through which evidence-based preventive interventions affect health risk behaviors are discussed.

Keywords: parental monitoring, negative errors, adolescent substance use, adolescent risky sexual behavior, divorced families

Because adolescent health risk behaviors such as underage alcohol and illicit drug use, and risky sexual behaviors have multiple negative consequences for functioning and are of substantial cost to society (Brook, Cohen, & Brook, 1998; Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation [PIRE], 1999), preventive efforts aimed at their reduction have significant public health implications. Youth from divorced families are an important group for studying pathways to health risk behaviors given their increased risk for these outcomes (e.g., Kessler, Davis, & Kendler, 1997) and the high prevalence of divorce (U.S. Census Bureau, 2005).

Although there are increasing numbers of longitudinal randomized prevention trials demonstrating the efficacy of prevention programs for adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior, there continues to be a critical need to understand how such programs work, and most notably, the mechanisms that account for long-term program effects (Ginexi & Hilton, 2006). Efforts to identify mediating mechanisms of these program effects have shown inconsistent findings. For example, Dishion, Nelson, and Kavanagh (2003) showed that parental monitoring mediated program effects on substance use for ninth graders with high levels of risk three years earlier and DeGarmo et al. (2009) found that their school-based preventive intervention had significant indirect effects on reductions in growth in of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use through intervention effects on reduced playground aggression and increased family problem solving, with effects being greater for girls than boys. However, Ennett et al. (2001) found that parental monitoring and rule-setting about substance use did not mediate their preventive intervention’s effects on adolescent substance use. Given these inconsistent findings, additional research is needed to elucidate the processes through which preventive interventions impact youth substance use. One factor that may account for the differential mediation findings is that some studies examined mediation across high and low risk, whereas others did not. In the area of problem behavior, there is a considerable literature which has found that prevention program effects are stronger for those at higher risk for adjustment problems at program entry than those at lower risk (e.g., Dishion et al., 2003; Olds et al., 1998). If the high risk participants are most likely to benefit from prevention programs it follows logically that mediation of program effects is most likely to be found within the high risk subgroup.

Using a follow-up of a sample that, in childhood, participated in a randomized trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families (the New Beginnings Program; NBP; Wolchik et al., 2002), the current research augments the limited research on mediation of program-induced reductions in adolescent health risk behavior in three ways. First, it tests mediation using models that include program by risk interaction terms. Second, it examines both family-level (e.g., parenting) and child-level (e.g., coping) variables that have been linked with health risk behaviors in prior research. Third, the sample, which consists of youth from divorced families, is a group at elevated risk for substance use problems and risky sexual behavior.

In the NBP, mothers and their children ages 9–12 were randomly assigned to the Mother Program (MP); Mother plus Child Coping Program (MPCP); or a Literature Comparison condition (LC). The mother program focused on improving effective discipline and mother-child relationship quality; the child program focused on promoting adaptive appraisals and coping. At post-test, the MP led to improvements in mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline and maternal attitudes toward the father-child relationship relative to the LC. Contrary to expectation, the MP and the MPCP did not have differential effects on the putative mediators (e.g., adaptive coping) nor mental health outcomes (Wolchik et al., 2000). Analyses of the 6-year follow-up data found, among other outcomes, positive program effects on substance use for those with high risk at program entry and number of sexual partners regardless of pre-test risk (see Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, & Winslow, 2007).

This study augments previous research on the mediational paths of the NBP (e.g., Wolchik et al., 1993, Tein, Sandler, MacKinnon, & Wolchik, 2004; Zhou, Sandler, Millsap, Wolchik, & Dawson-McClure, 2008) that have shown that mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline mediated program effects on a variety of mental health outcomes but not those on substance use nor risky sexual behavior. The current study builds on this previous research by examining whether the NBP’s effects on substance use and risky sexual behavior can be explained through its effects on negative errors, adaptive coping and parental monitoring, each of which has been found to relate to health risk behaviors in correlational studies.

The focus on negative errors and adaptive coping is based on a stress and coping conceptual framework in which appraisals and coping strategies account for the effect of stressful events on mental health problems (Lazarus and Folkman (1984). Appraisals have been consistently shown to relate to mental health problems for individuals exposed to stressors, including divorce (e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Mazur, Wolchik, Virdin, Sandler, & West, 1999). Negative errors or inaccuracies in interpreting events are appraisals in which negative information is overemphasized at the expense of positive or ambiguous aspects of events (hereafter termed “negative errors”) (Leitenberg, Yost, & Carroll-Wilson, 1986). Adaptive coping includes active coping strategies or behavioral or cognitive responses designed to change the stressful event itself or how one thinks about it (Carver et al., 1989) and coping efficacy, the belief that one can effectively manage the demands of and emotions caused by stressful events (Sandler, Tein, Mehta, Wolchik, & Ayers, 2000).

Research provides support for negative errors and adaptive coping as plausible mediators of the NBP’s program effects on health risk behaviors. Researchers have shown that negative errors mediate the relation between negative events and substance use (e.g., Blackson, Tarter, Loeber, Ammerman, & Windle, 1996), and that negative errors also mediate the relation between stressful events and externalizing problems (e.g., Grych, Raynor, & Fosco, 2004; Kerig, 1998), a well-established developmental antecedent of health risk behaviors (e.g., Dishion, Capaldi, Spracklen, & Li, 1995). High levels of active coping have been shown to be related to lower levels of adolescent substance use (see Wills & Filer, 1996 for a review) and risky sexual behavior (e.g., Rotheram-Borus et al., 2001). Coping efficacy has been shown to negatively relate to mental health problems and to mediate the relations between active coping and low levels of mental health problems (Sandler et al., 2000). Research also supports the links between parenting and youth coping and negative errors. Correlational research shows that parental warmth, acceptance and support are positively associated with active coping (see Power, 2004 for a review). Although more limited, there search on coping efficacy has shown positive relations between maternal support and coping efficacy (e.g., Smith et al., 2006). In the current sample, Velez, Wolchik, Tein and Sandler (2009) showed that program-induced improvements in mother-child relationship quality led to increases in active coping and coping efficacy at the 6-year follow-up. Given that children with warm, accepting parents have been shown to be at reduced risk for negative errors (e.g., Grych et al., 2004) and that the NBP improved mother-child relationship quality, program effects on negative errors at the 6-year follow-up are plausible.

This study also tested whether program effects on parental monitoring of adolescents’ activities accounted for program-induced reductions in health risk behaviors. From the perspective of Problem Behavior Theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977), adolescent health risk behaviors are due to a lack of social control and deficits in shaping of prosocial, conventional behavior. Higher levels of monitoring have been associated with later initiation and lower consumption of alcohol and illicit substances (e.g., Dishion et al., 1995) and fewer sexual partners (e.g., Li, Stanton, & Feigelman, 2000). Program effects on monitoring were expected on the basis of the program-induced improvements in mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline.

The current study examined whether the NBP program effects on health risk behaviors were mediated by parental monitoring, negative errors and adaptive coping at the 6-year follow-up. It was hypothesized that the program-induced improvements in monitoring, adaptive coping, and negative errors would account for program effects on substance use and risky sexual behavior six years after the program.

Method

Procedure

Two-hundred and forty children ages 9–12 (49% female) and their mothers were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: MP (N=81); MPCP (N=83); and LC (N=76). The Child Coping Program (i.e., CP), one part of the MPCP, was administered separately in groups that met concurrently with the MP. The MP in both the MP and MPCP conditions was identical. Eligibility criteria, described in detail elsewhere (Wolchik et al., 2000), included the divorce occurring within the past two years; mother being the primary residential parent; mother having not remarried, and neither the mother nor child currently receiving psychological treatment. Because of the preventive nature of the intervention and ethical concerns, families were excluded and referred for treatment if the child endorsed an item about suicidality or exhibited severe levels of depressive symptoms or externalizing problems. In families with multiple children in the age range, one was randomly selected to be interviewed.

Participants were primarily recruited using court records of divorce decrees; about 20% responded to media advertisements. The 671 families (50%) who met eligibility criteria in a phone screen were invited to participate in an in-home recruitment visit. Of the 453 families that completed home visits, 315 completed pre-test interviews. Forty-nine families were found to be ineligible at pre-test and 26 refused participation in the study between pre-test and assignment to condition. Thirty-six percent of those who were eligible were randomized to one of the three intervention conditions (N=240). Acceptors reported significantly higher incomes (p =.03) and maternal education (p = .01), and fewer offspring than refusers (p =.01) (Wolchik et al., 2002). At 6-year follow-up, 218were re-interviewed (91%). In Zhou et al.’s (2008) attrition analyses that compared families assessed at 6-year follow-up (n= 218) with those not assessed (n= 22) on baseline demographic variables (e.g., per capita income), internalizing problems and externalizing problems, there were no significant attrition or condition × attrition interaction effects. Thus, attrition did not threaten internal or external validity.

The variables used in this study were assessed in late childhood (pre-test; Time 1) and six years later in adolescence (6-year follow-up; Time 2). The measures of the mediators were taken from the 6-year assessment. The parental monitoring measure was administered only at 6-year follow-up. Although negative errors and coping were assessed at pre-test, and at 3-month, 6-month and 6-year follow-ups, data from the 6-year follow-up were used based on research showing age-related increases in the ability to consider the negative relevance of events for one’s well-being (e.g., Turner & Cole, 1994) are related to the effects of negative errors on outcomes.

At pre-test, after confidentiality was explained, parents signed consent forms and youth signed assent forms. At the 6-year follow-up, parents and adolescents who were18 or older signed consent forms; youth 17 years old or younger signed assent forms. Parents and youth were interviewed separately. Families were compensated $45 for participation at pre-test; parents and adolescents received $100 each at the 6-year follow-up.

Sample Characteristics

Ethnicity for mothers interviewed at Time 1 was 90% Caucasian, 6% Hispanic, and 4% other, and 89 % Caucasian, 6 % Hispanic, and 5 % other for mothers interviewed at Time 2. Mean yearly income was $20,001 -$25,000 at Time 1 and $50,001 – $55,000 at Time2. At Time 1, 63%, 35% and 3% of the families had sole maternal legal custody, joint custody, and split custody, respectively. At Time 2, 53%, 46% and 1% of families had sole maternal legal custody, joint legal custody, and paternal custody, respectively. At Time 2, 80% of the youth lived with their mothers, 11% lived with their fathers, and 9% lived independently. Youth averaged 10.9 years and 16.7 years at Time 1 and Time 2, respectively.

Intervention

The program for mothers used multiple empirically-supported strategies to affect the intervention targets or putative mediators (i.e., mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline, interparental conflict, and father-child contact). Putative mediators targeted in the child component were active coping, avoidant coping, coping efficacy, negative errors, and quality of the mother-child relationship. In the LC, mothers and children received books and syllabi related to coping with divorce. See Wolchik et al. (2000, 2007) for further details.

Measures of Predictors

Demographics

At pre-test, mothers completed items about their children’s age, their own ethnicity and income, and other demographics. Parents provided information such as income, treatment history, and family configuration at the 6-year follow-up.

Risk

Previous analyses showed that the program benefit in reducing substance use was greater for youth who were at risk for developing later adjustment problems (e.g., Wolchik et al., 2007). Thus, the risk index developed by Dawson-McClure, Sandler, Wolchik, and Millsap (2004) was included as a predictor. This index was a composite of the pre-test variables that were the best predictors of multiple adolescent outcomes in the control group: externalizing problems and an environmental stress composite that assessed a broad range of common divorce-related stressors (e.g., negative events that occurred to the child, interparental conflict, maternal distress; for more information about the components of this index, see Dawson-McClure et al. [2004]). Using data from the NBP control group, Dawson-McClure et al. (2004) found that risk scores were significantly correlated with internalizing problems and externalizing problems, substance use, and competence six years later. Also, the risk index had a sensitivity of .75 and a specificity of .73 and an odds ratio of 8.14 for mental disorder, indicating that the odds of having a diagnosis at 6-year follow-up were 8.14 times higher for youth with high levels of risk than for youth with low levels of risk (Dawson-McClure et al., 2004).

Negative errors

Youth and mothers rated whether events on the50-item Negative Life Events Scale – Child (NLES-C; Program for Prevention Research, 1992) occurred to the youth in the past month. The NLES-C includes events that are primarily beyond the child’s control and uncontaminated by child mental health problems. Construct validity has been established for this instrument (e.g., Sandler et al., 1986). Youth rated negative errors for the most upsetting event on the NLES-C (based on the mean ratings of upsettingness of events as rated by prior samples of youth who had experienced the event [i.e., using a 5-point scale; 1 = “not at all upsetting” and 5 = “very upsetting”]). Negative errors were assessed using the 4-item subscale of the What I Felt Scale (WIFS; Sandler, Ayers, Bernzweig, Wompler, Harrison, & Lustig, 1990; Sheets, Sandler, & West, 1996; 1= “didn’t think this”; 4 = “thought it a lot”). Youth completed one item each for catastrophizing (“You thought that this was going to lead to lots of big problems”), overgeneralizing (“You thought that things like this would always keep happening”), personalizing (“You thought that nothing ever goes right for you”), and selective abstraction (“You thought that a lot of things were going badly for you”). These items were summed. Negative errors scores were significantly, positively related to child-reported anxiety (r=.46), depression (r =.32), and externalizing problems (r =.27) at pre-test. At pre-test and 6-year follow-up, α’s were.78 and .77, respectively.

Adaptive Coping

Active coping efforts used in the last month were assessed with the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (Ayers, Sandler, West & Roosa, 1996; 1= “never”; 4= “most of the time”). This measure includes six 4-item subscales assessing direct problem-solving (e.g., “You did something to make things better”), cognitive decision making (e.g., “You thought about which things are best to do to handle the problem”), seeking understanding (e.g., “You tried to figure out why things like this happen”), positive focus (e.g., “You reminded yourself that overall things are pretty good for you”), optimism (e.g., “You told yourself that things would get better”), and control (e.g., “You reminded yourself that you knew what to do”). The mean of the items in each subscale was computed and standardized, and a grand mean of the six subscale means was then computed. Active coping scores have been shown to relate to fewer internalizing problems longitudinally (Sandler, Tein, & West, 1994). At pre-test and 6-year follow-up, α’s were .82 and .88 respectively.

Coping efficacy was measured with seven items about youths’ satisfaction with their handling of past negative events and problems, and anticipated effectiveness in handling future events and problems (Sandler et al.; 2000; e.g., “Overall, how good do you think you have been in handling problems during the last month?”). Responses (1= “not at all good”; 4= “very good”) were summed. Sandler et al.(2000) demonstrated longitudinal relations between coping efficacy and internalizing problems and externalizing problems. Pre-test α was .74; α at 6-year follow-up was .82. Standardized scores on the coping and efficacy measures were averaged.

Parental monitoring

The 13-item Assessment of Child Monitoring Scale (ACMS; Hetherington et al., 1992; 1=”nothing”; 5= “everything”) was used to assess mothers’ and youths’ perceptions of mothers’ knowledge of youths’ participation in high-risk behaviors at the 6-year follow-up. Items included “How much do you know about your child’s use of alcohol?” (mother). Total scores were averaged across reporters to form a composite. Coefficient alphas were .91 and .87 for mother and adolescent reports, respectively.

Measures of Covariates

Age

Age was used as a covariate on the basis of research that has shown a strong, positive association between youth age and health risk behaviors (e.g., Dishion et al., 1995; Houck et al., 2006).

Negative errors and adaptive coping

Pre-test measures of negative errors and adaptive coping were used to control for prior levels of these variables on levels of these variables at the 6-year follow-up.

Parent-adolescent open communication

Parental monitoring was not assessed prior to the 6-year follow-up. Parent-youth open communication, assessed using the 10-item open communication subscale of the Parent – Adolescent Communication Scale (PACS; Barnes & Olson, 1982) was used as a covariate as a proxy for monitoring because it has been shown to be significantly, positively correlated with monitoring (e.g., Huebner & Howell, 2003). The standardized scores of mother and child reports were averaged. Pre-test alphas were .72 and .83 for the child-and mother-reported scores, respectively.

Measure of Criteria

Substance use

Adolescents completed the 50-item Monitoring the Future Scale (MTF; Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 1993). MTF scores have been shown to have substantial correlations with delinquency (Bachman, Johnston, & O’Malley, 1996). Frequencies of marijuana, alcohol, and other drug use in the past year were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = “0 occasions”; 7 = “40 or more occasions”). For each of 15 substance types, use was recoded as 0 (“0 occasions”) or 1 (greater than or equal to “1–2 occasions”); polydrug use was computed as the sum across all types of substances. The following measures were used: frequency of marijuana use (31% of the sample reported use), alcohol use (60% reported use), other drug use (i.e., use of drugs other than marijuana, such as cocaine; 21% reported use), and polydrug use (61%reported use of at least two substances, including alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs). To minimize Type I error, alcohol and marijuana use scores (r = .61) were standardized and averaged to form a composite. Prior analyses showed no significant program main effects or risk x program effects on tobacco use (Soper, 2008). Thus, mediation analyses were not conducted.

Risky sexual behavior

Number of partners with whom the adolescent had sexual intercourse in the past year was assessed using a single item from DeLamater and MacCorquodale’s (1979) Sexual Behavior Inventory.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Scores for number of sexual partners, other drug use, and polydrug use were positively skewed [4.0, 6.7, and 2.9, respectively] and had a kurtosis of 22.6, 55.4, and 10.7, respectively. It is not uncommon for health risk behaviors to be positively skewed in community samples (e.g., Chang, Halpern, & Kaufman, 2007). Because of the presence of non-normal variables in the models, the bootstrapping method (Efron, 1981) was used to minimize problems with distributional normality and homoskedasticity1. Pearson product moment correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 1, and do not suggest multicollinearity.

Table 1.

Zero-Order Correlations Between Study Variables and Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gendera | -- | .04 | .22** | −.05 | .01 | −.06 | −.27*** | .06 | −.02 | .08 | .13 | .11 | .10 | .12 | .04 |

| 2. T2 Ageb | -- | −.04 | −.10 | −.04 | −.09 | −.21** | −.14* | .05 | .38*** | .21** | .33*** | .19** | .18* | .29*** | |

| 3. T1 Risk | -- | −.34*** | .21** | −.13* | −.16* | .15* | −.23** | .14* | .23** | .20** | .22** | .14* | .07 | ||

| 4. T1 Parent-Child Communication – M & C | -- | −.18** | .37*** | .27*** | −.02 | .18* | −.14* | −.13 | −.15* | −.08 | .02 | .01 | |||

| 5. T1 Negative Errors | -- | −.18** | −.06 | .11 | −.07 | .21** | .17* | .21** | .21** | .14* | .07 | ||||

| 6. T1 Adaptive Coping | -- | .19** | −.08 | .21** | −.20** | −.19** | −.21** | −.13 | −.06 | −.14* | |||||

| 7. T2 Parental Monitoring – M & C | -- | −.11 | .31*** | −.40** | −.44*** | −.47*** | −.47*** | −.30*** | −.29*** | ||||||

| 8. T2 Negative Errors | -- | −.18* | .10 | .20** | .17* | .25*** | .23** | .13 | |||||||

| 9. T2 Adaptive Coping | -- | −.10 | −.23** | −.19** | −.22** | −.15* | −.22** | ||||||||

| 10. T2 Alcohol Use | -- | .61*** | .90*** | .62*** | .37*** | .34*** | |||||||||

| 11. T2 Marijuana Use | -- | .90*** | .75*** | .52*** | .36*** | ||||||||||

| 12. T2 Alcohol and Marijuana Use Composited | -- | .77*** | .50*** | .39*** | |||||||||||

| 13. T2 Polydrug Use | -- | .84*** | .37*** | ||||||||||||

| 14. T2 Other Drug Use | -- | .44*** | |||||||||||||

| 15. T2 Number of Sexual Partners | -- | ||||||||||||||

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | 0.5 (0.5) | 16.4 (1.1) | 0.0 (0.6) | 42.9 (4.2) | 7.0 (3.1) | 0.0 (0.9) | 51.5 (8.0) | 6.5 (2.7) | 0.7 (0.9) | 3.0 (2.0) | 2.0 (1.8) | 0.0 (0.9) | 1.7 (2.2) | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.7 (1.3) |

Note. The N for each cell ranges from 193 – 240. Unless otherwise noted, measures are youth-reported.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

This is a dummy-coded variable with 0 = female and 1 = male.

T1 represents pre-test; T2 represents 6-year follow-up.

Combining MP and MPCP groups

Although the child program was designed to increase adaptive coping and to decrease negative errors, the MP and MPCP groups did not differ at post-test on these variables (Wolchik et al., 2000). Further, prior comparisons of the MP and MPCP, showed that only one main or interactive effect of 46 outcomes assessed at post-test and short-term follow-ups was significant or marginal (Wolchik et al.., 2007). At the 6-year follow-up, comparison of the MP and MPCP conditions showed fewer than chance differences (Wolchik et al., 2002) and none of the comparisons of the MP vs. MPCP on the putative mediators was significant at the 6-year follow-up (Wolchik et al., 2007). To ensure that the two intervention groups could be combined into a single group for the current analyses, for each model, a Box’s M analysis was performed to examine whether the relations among the variables were similar in the MPCP and MP groups. Results revealed that the variance/covariance matrices were significantly different only for the model that used risky sexual behaviors as the outcome (Box’s M = 74.93; F (45) = 1.54, p = .01; χ2(45) = 69.22, p = .01). Thus, except for the model with the risky sexual behaviors outcome, the MP and MPCP were combined.

Outlier analyses

To assess for the possible influence of outliers, regression diagnostic indices of leverage, influence, and distance were examined. According to well-established criteria proposed by Neter, Kutner, and Wasserman (1989), Stevens (1984), and Cook (1977), no outliers were present.

Missing data

Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was employed to handle missing data. FIML uses all available information (i.e., does not delete incomplete data) and has been shown to produce unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors (Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

Analytic Method

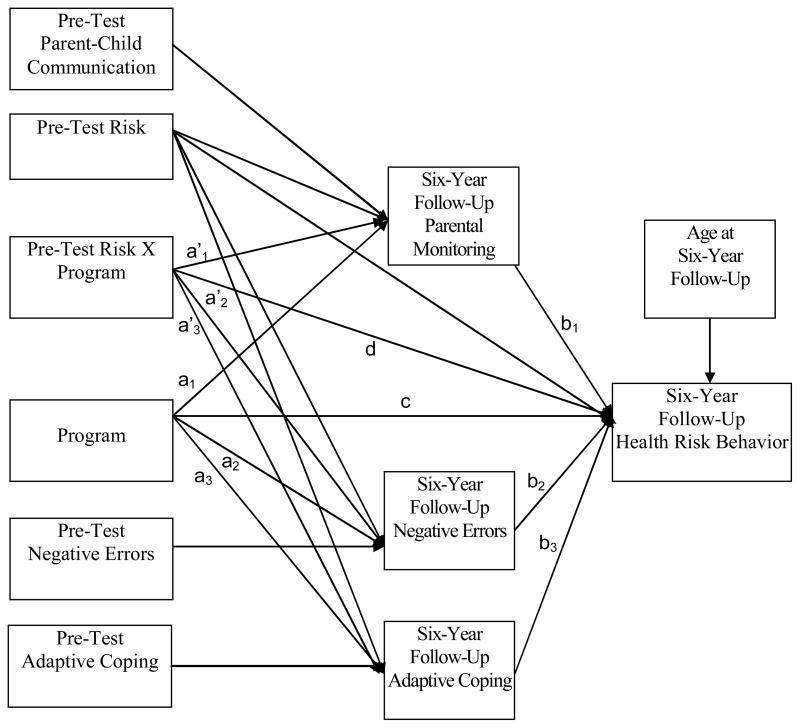

Because prior findings that program effects on substance use occurred only for those with high levels of risk (Wolchik et al., 2007), mediation of program effects as moderated by the pre-test risk index was tested using path analysis with Mplus (Múthen & Múthen, 2007). Prior analyses showed program effects on risky sexual behavior irrespective of pre-test risk (Wolchik et al., 2007), so the direct path from the risk by program interaction term to risky sexual behavior was not included. Four models were tested: composited alcohol and marijuana, polydrug use, other drug use, and risky sexual behavior. All mediators were entered simultaneously to predict the outcomes (Figure 1). In addition to the covariates mentioned above, gender was considered as a covariate, but dropped because there were no significant direct effects of gender or gender x program on the outcomes. Program, pre-test risk, and the interaction of risk with program served as predictors. Program was dummy coded using 0 (LC) or 1 (MP or MPCP). Program effects on mediators were tested by examining the significance of the paths from the program to the mediators (a1, a2, and a3). The extent to which mediation of program effects was moderated by pre-test risk was reflected by a significant program x risk interaction term to the mediators (a′1, a′2, and a′3). Except for risky sexual behavior, the interaction between pre-test risk and program was included with a direct path to the outcome. To assess mediation, the significance of the path from the program to the mediators (a path) and that from the mediators to the outcome (b path) was examined through the confidence interval of the indirect path, ab, using the bias-corrected bootstrap test (MacKinnon et al., 2002). Following Tein et al.’s (2004) method of testing if mediation effects differed across high and low risk when significant program x risk interaction effects occurred, if the paths including the risk by program term to the mediator (a′ path) and the mediator to the outcome term (b path) were significant, post hoc evaluations of simple mediation effects were conducted at −1SD and +1SD risk values.

Figure 1.

Meditational path analytic model explaining NBP effects on substance use and risky sexual behavior.

Results for Alcohol and Marijuana Use Outcome

As shown in Table 2, for the composite of alchohol and marijuana use, significant risk by program effects on monitoring (a′1 path; unstandardized path coefficient; B = 5.85, SE = 2.03; p < .01), negative errors (a′2 path; B = −1.78, SE = 0.82; p < .05), and adaptive coping (a′3 path; B = .72, SE = .25; p < .01) were found. (Analyses conducted separately for alcohol use and marijuana use showed highly similar patterns to those for the composite score.) The b path was significant for monitoring and negative errors but not for coping. Monitoring was negatively related to alcohol and marijuana use (B = −.04, SE = .01; p < .01). However, negative errors scores were positively related to alcohol and marijuana use (B = .04, SE = .02; p < .05). Post hoc tests of mediation effects indicated that for adolescents with high risk at pre-test, monitoring significantly mediated the program effects on alcohol and marijuana use, such that program participation increased monitoring (B = 5.13, SE = 1.94; p < .01), and increased monitoring was significantly, negatively related to substance use (B = −.04, SE = .01; p < .001). The mediation effect of monitoring at high risk levels with a 99% confidence interval was −.20 (−.41, −.03), which was significant. The program did not significantly increase monitoring for adolescents with low risk. Post hoc probing showed that for adolescents with high risk scores at pre-test, the effect of the program on negative errors was not significant. For those with low risk pre-test scores, contrary to expectation, the program increased negative errors (B = 1.10, SE = .45; p < .05). The mediation effect of negative errors to alcohol and marijuana use at low risk with a 95% confidence interval was .05 (.01, .13), which was significant. Consistent with Wolchik et al.’s (2007) findings, a significant risk by program interaction effect on adaptive coping was found.

Table 2.

Summary of the Path Coefficients for Mediational Path Analytic Model with Alcohol and Marijuana Use Outcome.

| a Program → Mediator | a′ Risk X Program → Mediator | b Mediator → Outcome | c Program → Outcome | d Risk X Program → Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 M-C Monitoring → T2 Alcohol and Marijuana Use (C) | a1 = 1.60 (1.20) | a′1 = 5.85**(2.03) | b1 = −.04*** (.01) | −.19 (.13) | −.48* (.24) |

| High Risk Adolescents | 5.13**(1.94) | −.04***(.01) | −.49*(24) | ||

| Low Risk Adolescents | −1.98 (1.50) | −.04***(.01) | .11 (.13) | ||

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Negative Errors (C) → T2 Alcohol and Marijuana Use (C) | a2 = −.01 (.45) | a′2 = −1.78*(.82) | b2 = .04*(.02) | −.19 (.13) | −.48* (.24) |

| High Risk Adolescents | −1.11 (.85) | .04* (.02) | −.49* (.24) | ||

| Low Risk Adolescents | 1.10*(.45) | .04* (.02) | .11 (.13) | ||

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Adaptive Coping (C) → T2 Alcohol and Marijuana Use (C) | a3 = .07 (.14) | a′3 = .72**(.25) | b3 = −.02 (.06) | −.19 (.13) | −.48* (.24) |

| High Risk Adolescents | .50* (.23) | −.02 (.06) | −.49* (.24) | ||

| Low Risk Adolescents | −.37* (.19) | −.02 (.06) | .11 (.13) |

Notes. Values presented are unstandardized path coefficients (with standard error in parentheses) for the mediational and direct paths for the group when risk = 0, as well as at high and low risk. Significant paths are highlighted in bold. M-C = mother and child report; C = child report.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Results for Polydrug Use

As shown in Table 3, in the models for polydrug use, the findings of program and risk by program effects to the mediators are similar to those in Table 2 with minor changes due to FIML. Monitoring was significantly, negatively related to polydrug use (i.e., the b path; B = −.12, SE = .02; p < .001); negative errors were positively, marginally related to polydrug use (B = .15, SE = .08; p < .10). The findings of the post hoc tests indicated that for the high risk group, the mediation effect of parental monitoring with a 95% confidence interval was −.11 (−.20, −.02), which was significant. There was no mediation effect for the low risk group.

Table 3.

Summary of the Path Coefficients for Mediational Path Analytic Model with Polydrug Use Outcome.

| a Program → Mediator | a′ Risk X Program → Mediator | b Mediator → Outcome | c Program → Outcome | d Risk X Program → Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 M-C Monitoring → T2 Polydrug Use (C) | a1 = 1.53 (1.21) | a′ 1 = 5.57**(2.06) | b 1 = −.12*** (.02) | −.15 (.34) | −.82 (.78) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | 4.94*(1.97) | −.12***(.02) | −.67 (.77) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | −1.87 (1.50) | −.12***(.02) | .37 (.30) | ||

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Negative Errors (C) → T2 Polydrug Use (C) | a2 =−.01 (.45) | a′2 = −1.78*(.82) | b2 = .15τ (.08) | −.15 (.34) | −.82 (.78) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | −1.11 (.85) | .15τ (.08) | −.67 (.77) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | 1.10* (.45) | .15τ (.08) | .37 (.30) | ||

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Adaptive Coping (C) → T2 Polydrug Use (C) | a3 =.07 (.14) | a′ 3 =.72**(.25) | b3 = −.06 (.16) | −.15 (.34) | −.82 (.78) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | .50*(.23) | −.06 (.16) | −.67 (.77) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | −.38* (.19) | −.06 (.16) | .37 (.30) |

Notes. Values presented are unstandardized path coefficients (with standard error in parentheses) for the mediational and direct paths for the group when risk = 0, as well as at high and low risk. Significant paths highlighted in bold. M-C = mother and child report; C = child report.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Results for Other Drug Use

The paths from program and risk by program terms to the mediators are similar to previous findings. As shown in Table 4, the b path was significant for monitoring but not for negative errors or adaptive coping. Monitoring was negatively related to polydrug use (B = −.16, SE = .06; p < .05). The findings of the post hoc tests indicated that for those with high risk scores, the mediation effect of monitoring with a 95% confidence interval was −.07(−.13, −.01), which was significant. For those with low risk, there was no mediation effect.

Table 4.

Summary of the Path Coefficients for Mediational Model with Other Drug Use Outcome.

| a Program → Mediator | a′ Risk X Program → Mediator | b Mediator → Outcome | c Program → Outcome | d Risk X Program → Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 M-C Monitoring → T2 Other Drug Use (C) | a 1 = 1.59 (1.21) | a′ 1 = 5.78**(2.07) | b1 = −.16* (.06) | −.34 (1.02) | −1.65 (2.57) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | 5.10**(1.96) | −.16*(.06) | −1.40 (2.50) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | −1.96 (1.51) | −.16*(.06) | .71 (.85) | ||

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Negative Errors (C) → T2 Other Drug Use (C) | a 2 = −.01 (.45) | a′2 = −1.78* (.82) | b2 = .46 (.34) | −.34 (1.02) | −1.65 (2.57) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | −1.11 (.85) | .46 (.34) | −1.40 (2.50) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | 1.10*(.45) | .46 (.34) | .71 (.85) | ||

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Adaptive Coping (C) → T2 Other Drug Use (C) | a 3 = .07 (.14) | a′3 = .72**(.25) | b3 = −.12 (.39) | −.34 (1.02) | −1.65 (2.57) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | .50* (.23) | −.12 (.39) | −1.40 (2.50) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | −.38* (.19) | −.12 (.39) | .71 (.85) |

Notes. Values presented are unstandardized path coefficients (with standard error in parentheses) for the mediational and direct paths for the groups when risk = 0, as well as at high and low risk. Significant paths are highlighted in bold.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Results forRisky Sexual Behavior

Given the results of the Box’s M test, separate models for the MP vs. LC and MPCP vs. LC were conducted (Tables 5 and 6, respectively). For the comparison of MP vs. LC, there were significant risk by program effects on parental monitoring (B = 7.97, SE = 2.16; p < .001), negative errors (B = −2.02, SE = 0.88; p < .05), and adaptive coping (B = .84, SE = .26; p < .001). The b path was significant for coping (B =−.36, SE = .16; p < .05), marginally significant for monitoring (B = −.02, SE = .01; p < .10), and non-significant for negative errors. Post hoc probing showed that for adolescents with high risk scores at pre-test, the mediation effect of coping with a 95% confidence interval was −.16 (−.49, −.02), which was significant. For the high risk subgroup, the program had a positive effect on coping (B = .45, SE = .23; p < .05), which in turn, related to fewer risky sexual behaviors. For the low risk subgroup, there was a significant mediation effect with a 99% confidence interval of .21 (.01, .71). The program significantly decreased adaptive coping (B = −.59, SE = .24; p < .01) for the low-risk subgroup, although the effect of coping to reduce risky sexual behaviors was consistent with the model for youth with high pre-test risk scores.

Table 5.

Summary of the Path Coefficients for Mediational Model with Number of Sexual Partners for Mother Program (MP).

| a Program → Mediator | a′ Risk x Program → | b Mediator → Outcome | c Program → Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 M-C Monitoring → T2 Partners | a1 = .69 (1.32) | a′1 = 7.97*** (2.16) | b1 = −.02τ (..01) | −.44τ (.24) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | 5.66***(1.90) | −.02τ (.01) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | −4.26* (1.86) | −.02τ (.01) | ||

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Negative Errors (C) → T2 Partners | a2 = .28 (.08) | a′ 2 = −2.02*(.88) | b2 = .09 (.06) | −.44τ (.24) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | −1.09 (.79) | .09 (.06) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | 1.66**(.60) | .06 (.05) | ||

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Coping (C) → T2 Sexual Partners | a3 = −.08 (.17) | a′ 3 =.84***(.26) | b3 = −.36* (.16) | −.44τ (.24) |

| High-Risk Adolescents | .45*(.23) | −.36*(.16) | ||

| Low-Risk Adolescents | −.59**(.24) | −.36*(.16) |

Notes. Values presented are unstandardized path coefficients (with standard error in parentheses) for the mediational and direct paths for the group when risk = 0, and at high and low risk. Significant paths are highlighted in bold. M-C = mother and child report; C = child report.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Table 6.

Summary of the Path Coefficients for Mediational Model with Number of Sexual Partners for Combined Mother and Child Program (MPCP).

| a Program → Mediator | a′ Risk x Program → Mediator | b Mediator → Outcome | c Program → Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 M-C Monitoring → T2 Partners (C) | a1 = 1.61(1.33) | a′1 = 2.79 (2.12) | b1 = −.02(.01) | −.49*(.22) |

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Negative Errors (C) → T2 Partners (C) | a2 = −.01 (.09) | a′ 2 = −1.11(..93) | b2 = .01 (.04) | −.49*(.22) |

| T1 Risk X Program → T2 Coping (C) → T2 Sexual Partners (C) | a3 = .09 (.17) | a′ 3 =.57τ (.30) | b3 = −.24(.16) | −.49*(.22) |

Notes. Values presented are unstandardized path coefficients (with standard error in parentheses) for the mediational and direct paths for the group when risk=0. Values at high and low risk were not presented because there were no significant interactive effects with risk. Significant paths are highlighted in bold. M-C = mother and child report; C = child report.

p < .10,

p < .05.

As shown in Table 6, for the MPCP condition, the paths from the risk by program term to the monitoring and negative errors mediators were non-significant and the path from the risk by program to adaptive coping was marginal (B = .57, SE = .30; p < .10). None of the mediators had significant effects on the outcomes. A significant main effect of program to reduce risky sexual behavior that was previously demonstrated by Wolchik et al.(2007) was replicated (i.e., B = −.49, SE = .22; p < .05).

Discussion

This study tested three plausible mediators of previously demonstrated program effects of the NBP on health risk behaviors six years after program completion – parental monitoring, adaptive coping and negative errors. The results indicated that parental monitoring mediated the effects of the NBP on substance use and that adaptive coping mediated the NBP effects on risky sexual behavior. More specifically, the program increased parental monitoring and parental monitoring decreased alcohol and marijuana use, polydrug use, and other drug use for youth with high but not low risk of developing adjustment problems. Also, for youth with high risk, adaptive coping mediated the program effects on risky sexual behavior for youth in the MP only condition. Contrary to expectation, in the analyses involving risky sexual behavior, the MP decreased adaptive coping for adolescents with low levels of risk. In addition, contrary to expectation, the program increased negative errors for adolescents with low levels of risk in the analyses on substance use and risky sexual behavior.

The current findings augment the limited prior research focused on mediators of preventive intervention effects on health risk behaviors. Dishion et al. (2003) found that parental monitoring mediated program effects on reductions in substance use three years after program participation. Prado et al. (2007) found that a composite of parental involvement, parent-adolescent communication, parental warmth, and family support mediated intervention effects on substance use and risky sexual behavior over a 2-year period. The current study extends this prior research by demonstrating mediation effects in a sample with elevated risk of developing substance use problems (children from divorced families) over a longer follow-up period (six years). Further, the current study tested multivariate mediational models, which allowed the independent effects of the mediators to be assessed.

The current findings have implications for understanding the development of health risk behavior. By demonstrating that the program improved parental monitoring, and that experimentally-induced changes in parental monitoring accounted for program effects to reduce substance use, the current study provides further evidence for the role of monitoring in the development of some health risk behaviors. The findings are consistent with Problem Behavior Theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977), in which strong parental-environmental controls, such as high levels of parental monitoring, shape problem (e.g., substance use) or prosocial adolescent behaviors.

The program effects on substance use through parental monitoring are interesting to consider in the context of the nature of the program. Unlike many programs that have demonstrated change in substance use (e.g., Bauman et al., 2001; Spoth, Clair, Shin, & Redmond, 2006), the NBP did not specifically address substance use nor parental monitoring of substance use. Most sessions focused on increasing effective listening skills, attention to positive behaviors, and effective discipline strategies (e.g., clear expectations; fair, meaningful and consistent consequences) and positive post-test program effects occurred on mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline. One possible explanation of the program effects on parental monitoring six years after the program is that short-term improvements in mother-child relationship quality increased the amount of youth-initiated sharing of information about friends and activities. It may also be that the parenting skills learned when offspring were in middle-to-late childhood provided a foundation for effectively monitoring health risk behaviors when it was developmentally appropriate. Alternatively, as mothers became more effective disciplinarians, youth may have been more likely to expect that their health risk behaviors would be monitored and that misbehaviors would have consequences (Lochman & Wells, 2002).

An important step in program dissemination is to identify and preserve core elements of the program that are critical to implement with a high degree of fidelity for positive program effects to be achieved. The current findings add to evidence on the role of positive parenting as a mediator of short-term (Tein et al., 2004) and longer-term (Zhou et al., 2008) program effects and support the view that the program components linked to improving parenting skills are central for achieving the positive effects of the NBP. Implementation efforts in community settings should ensure that these components are delivered with a high degree of fidelity.

For youth in families that received the MP only and who had high levels of risk, adaptive coping mediated program effects to reduce risky sexual behavior. Because adaptive coping skills were not taught in the MP, this effect needs to be explained through program-induced improvement in parenting. This explanation is consistent with prior correlational research that has shown that parental acceptance is related to higher levels of active coping (e.g., Kliewer, Fearnow, & Miller, 1996) and our research that showed that program-induced improvements in positive parenting led to improvements in youth coping (Velez et al., in press). The effect of adaptive coping to reduce risky sexual behavior may be due to youth’s use of coping to identify and prepare for risky situations and choose behaviors that are likely to result in less adverse outcomes (Pedlow & Carey, 2004).

For the risky sexual behavior analyses, it was surprising that participation in the MPCP condition did not increase coping, given that the MP condition alone affected adaptive coping at the same time point, and that the child component of the MPCP directly targeted increases in adaptive coping. An explanation of this puzzling effect will require additional investigation. In addition, the finding in the risky sexual behavior analyses that program participation led to decreases in adaptive coping for low-risk adolescents who were in the condition that included the MP only and the finding across all analyses that program participation led to increases in negative errors for those at low levels of risk are puzzling. These findings highlight the importance of including risk as a moderator of intervention effects and suggest that prevention scientists should exercise caution in including these mediators as targets for change in programs for low risk youth.

The lack of support for a mediational role of adaptive coping and negative errors on substance use is inconsistent with findings of correlational research that coping and negative errors are related to substance use (Wills & Filer, 1996). When active coping and negative errors were tested in single mediator models, their effects remained non-significant; thus, the lack of significant findings cannot be attributed to shared predictive variance in the multiple mediator models. Measurement choices may explain the lack of significant effects. The four-item measure of negative errors may have been insufficient to capture the range of errors that youth have about stressful events. Also, the coping measure assessed coping across multiple events, some of which may not have been highly stressful to the individual youth.

There are several limitations of this work. First, future research should assess other aspects of risky sexual behavior (e.g., inconsistent condom use and age at first intercourse). Second, the dependent variables were based on self-report. Future research should include parents’ and peers’ perspectives on health risk behaviors. Third, the mediators and outcomes were assessed contemporaneously, which can produce biased estimates of effects (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Future research with additional assessments is required to establish temporal precedence needed to strengthen causal relations. Fourth, the sample may be biased in ways that affect generalizability (i.e., use of multiple eligibility criteria; nearly exclusively middle-class and Caucasian).

Identification of the processes that account for preventive interventions effects and examination of whether these processes differ across subgroups are critical issues for prevention science that have theoretical and applied implications. The current findings extend prior research showing that parental monitoring accounted for long-term effects of a prevention program on health risk behaviors by demonstrating these effects in youth from divorced families, and over a longer period of follow-up. This is the first study to demonstrate long-term mediation effects of parental monitoring for an intervention that emphasized relationship building skills rather than directly addressed parental monitoring of substance use. Also, by supporting the role of high-quality parenting in promoting adaptive outcomes after parental divorce, the results provide evidence for the theoretical framework underlying the intervention (Wolchik et al., 1993).

Acknowledgments

The writing of this paper was funded by a Ruth L. Kirchstein National Research Service Award (1 F31023734-01) awarded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to Ana Soper while at Arizona State University, grants for the Prevention Research Center at Arizona State University (2 P30M439246-18 and 5 P30MH068685-3), and a grant for 6-year follow-up of the preventive intervention under study (1 R01MH057013-01A), which are gratefully acknowledged. We are also grateful to Laurie Chassin for her contribution to this paper, and to the families for their participation in the study.

Footnotes

When analyses failed to converge due to specification of outcomes as ordered categorical in Mplus, outcomes were treated as continuous, yielding convergence. Any correction in the test statistic necessary was addressed by bootstrapping.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/adb

References

- Ayers TS, Sandler IN, West SG, Roosa M. A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality. 1996;64:923–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. The Monitoring the Future Project After 22 Years: Design and Procedures, Paper 38. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, ISSR; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent adolescent communication scales. In: Olson DH, editor. Family inventories. St. Paul: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota, MN; 1982. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Foshee VA, Ennett ST, Pemberton M, Hicks KA, King TS, et al. The influence of a family program on adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:604–610. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackson TC, Tarter RE, Loeber R, Ammerman R, Windle M. The influence of paternal substance abuse and difficult temperament in fathers and sons on sons’ disengagement from family to deviant peers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1996;25:389–411. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Cohen P, Brook DW. Longitudinal study of co-occurring psychiatric disorders and substance use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:322–330. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier M, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JJ, Halpern CT, Kaufman JS. Maternal depressive symptoms, father’s involvement, and the trajectories of child problem behaviors in a US national sample. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:697–703. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing meditational models with longitudinal data: Myths and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RD. Detection of influential observations in linear regression. Technometrics. 1977;19:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-McClure S, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Millsap RE. Risk as a moderator of the effects of prevention programs for children from divorced families: A six-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:175–190. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019769.75578.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Eddy JM, Reid JB, Fetrow RA. Evaluating mediators of the impact of the linking interests of families and teachers (LIFT) multimodal preventive intervention on substance use initiation and growth across adolescence. Prevention Science. 2009;10:208–220. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0126-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater J, MacCorquodale P. Premarital sexuality. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi DM, Spracklen KM, Li F. Peer ecology of male adolescent drug use. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:803–824. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Kavanagh K. The Family Check-Up for high-risk adolescents: Motivating parenting monitoring and reducing problem behavior. Behavior oriented interventions for children with aggressive behavior and/or conduct problems [Special Issue] In: Lochman JE, Salekin R, editors. Behavior Therapy. Vol. 34. 2003. pp. 553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Nonparametric estimates of standard error. Biometrika. 1981;68:589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Foshee VA, Pemberton M, Hicks KA. Parent-child communication about adolescent tobacco and alcohol use: What do parents say and does it affect youth behavior? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ginexi E, Hilton T. What’s next for translation research? Evaluation & The Health Professions. 2006;29:334–347. doi: 10.1177/0163278706290409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Raynor SR, Fosco GM. Family processes that shape the impact of conflict on adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:649–665. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG, Anderson ER, Deal JE, Stanley Hagan M, Hollier EA, Lindner MS. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3) Serial No. 227. [Google Scholar]

- Houck CD, Lescano CM, Brown LK, Tolou-Shams M, Thompson J, DiClemente R, et al. “Islands of risk”: Subgroups of adolescents at risk for HIV. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:619–629. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner A, Howell L. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(2):71–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the future: Questionnaire responses from the nation’s high school seniors. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Survey Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig P. Moderators and mediators of the effects of interparental conflict on children’s adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:199–212. doi: 10.1023/a:1022672201957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the U.S. national comorbidity study. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1101–1119. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Fearnow MD, Miller PA. Coping socialization in middle childhood: Tests of maternal and paternal influences. Child Development. 1996;67:2239–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Pub. Co; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Leitenberg H, Yost L, Carroll-Wilson M. Negative cognitive errors in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:528–536. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Stanton B, Feigelman S. Impact of perceived parental monitoring on adolescent risk behaviors over 4 years. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells K. Contextual social-cognitive mediators and child outcome: A test of the theoretical model in the Coping Power program. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:945–967. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D, Lockwood C, Hoffman J, West S, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur E, Wolchik SA, Virdin L, Sandler IN, West SG. Cognitive moderators of children’s adjustment to stressful divorce events: The role of negative cognitive errors and positive illusions. Child Development. 1999;70:231–245. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neter J, Kutner M, Wasserman W. Applied linear regression analysis. Chicago: Irwin; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Olds D, Henderson CR, Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, et al. Long term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1238–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation. Costs of underage drinking. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile and Delinquency Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pedlow CT, Carey MP. Developmentally appropriate sexual risk reduction interventions for adolescence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:172–184. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TG. Stress and coping in childhood: The parents’ role. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:271–317. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S. Centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in hispanic adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:914–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Program for Prevention Research (PIRC) New beginnings program project documentation and codebook. Tempe, AZ: PIRC, Arizona State University; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Murphy DA, Futterman D, Duan N, Birnbaum JM, et al. An intervention for parents with AIDS and their adolescent children. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:400–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Bernzweig JA, Wampler TP, Harrison RJ, Lustig J. Categorization of children’s appraisal of threat. Tempe, AZ: PIRC, Arizona State University; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Ramirez R, Reynolds K. Life stress for children of divorce, bereaved, and asthmatic children. Poster presented at the American Psychological Association Convention; Washington, DC. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein JY, Mehta P, Wolchik SA, Ayers T. Coping efficacy and psychological problems of children of divorce. Child Development. 2000;71:1099–1118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein JY, West S. Coping, stress, and the psychological symptoms of divorce. Child Development. 1994;65:1744–1763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets V, Sandler I, West SG. Errors of negative events by preadolescent children of divorce. Child Development. 1996;67:2166–2182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Chassin L, Morris AS, Kupfer A, et al. Children’s coping strategies and coping efficacy: Relations to parent socialization, child adjustment, and familial alcoholism. Development and Psychopathology. 18:445–469. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606024X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper A. The role of negative appraisals in explaining effects of stress and a preventive intervention on substance use. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2008;70(03) UMI No. 3351518. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Clair S, Shin C, Redmond C. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on methamphetamine use among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:876–882. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JP. Outliers and influential data points in regression. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:334–344. [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M, Eddy JM, Reid JB. Detecting and describing preventive intervention effects in a universal school-based randomized trial targeting delinquent and violent behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:296–306. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tein JY, Sandler IN, MacKinnon DP, Wolchik SA. How did it work? Who did it work for? Mediation in the context of a moderated prevention effect for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:617–624. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JE, Cole DA. Development differences in cognitive diatheses for child depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22(1):15–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02169254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current population survey: 2004 annual social and economic supplement. 2005 Retrieved November 23, 2006, from http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/cps2004/tabC3-all.csv.

- Velez C, Wolchik SA, Tein J-Y, Sandler IN. Protecting children from the consequences of divorce: A longitudinal study of the effects of parenting on children’s coping processes. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01553.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Filer M. Stress-coping model of adolescent behavior problems. In: Ollendick TH, Prinz RJ, editors. Advances in clinical child psychology. Vol. 18. New York: Plenum; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Millsap RE, Plummer B, Greene SM, Anderson ER, et al. Six-year follow-up of a randomized, controlled trial of preventive interventions for children of divorce. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;28:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Weiss L, Winslow E. New Beginnings: An empirically-based program to help divorced mothers promote resilience in their children. In: Briesmeister JM, Schaefer CE, editors. Handbook of parent training. New York: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler I, Winslow EB, Smith-Daniels V. Programs for promoting parenting of residential parents: Moving from efficacy to effectiveness. Family Court Review. 2005;43:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, West SG, Sandler IN, Tein JY, Coatsworth D, Lengua L, et al. An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:843–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, West SG, Westover S, Sandler IN, Martin A, Lustig J, et al. The children of divorce parenting intervention: Outcome evaluation of an empirically based program. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:293–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00941505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Sandler IN, Millsap R, Wolchik SA, Dawson-McClure S. Mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline as mediators of the 6-year effects of the New Beginnings Program for children from divorced families. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:579–594. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]